1. Introduction

“

Health is created and lived by people within the settings of their everyday life; where they learn, work, play and love” is a frequently quoted item from the Ottawa Charter [

1]. Accordingly, researchers in health promotion point to the importance of positively involving different relevant settings and stakeholders in the intervention target group to promote competence-based, action-oriented, sustainable health and to prevent severe health inequalities [

2,

3,

4]. Promoting health across a multitude of settings, and thereby increasing the complexity of the approaches, also increases the demand for complexity-oriented means of understanding, interpreting and structuring the ways in which outcomes are processed, managed and implemented [

5].

Steno Health Promotion Research (SHPR) was established in Denmark in 2010 as a research and development unit with a humanistic and social research approach. Its vision is to be a leader in research and development within the areas of prevention and management of diabetes. What sets us apart from other health promotion units is our use of a set of five health promotion principles that constitute the framework for a new intervention paradigm. Our aim is to develop a comprehensive and integrated approach consisting of innovative, effective and sustainable models for diabetes management and prevention, where the target population is at the center of all processes. The five principles are: (1) A broad and positive health concept; (2) Participation and involvement; (3) Action and action competence; (4) A settings perspective and (5) Equity in health. After seven years of working with these principles and this research approach within health promotion research and development, we have gathered a wealth of experience from a wide range of interventions in a multitude of health promotion settings. Most of the interventions have been thoroughly evaluated, which gives us ample data to perform the present overarching evaluation of how the principles have worked when implemented in healthcare and prevention practices, as well as in research and development processes.

The background of the five principles derives from widespread critique of the so-called moralizing paradigm that has long characterized much of the work conducted within the field of health promotion, prevention and treatment. This paradigm is characterized by being expert-driven as opposed to user-driven, by its narrow focus on creating pre-defined behavioural changes and by exclusively focusing on avoiding or reducing the risk of disease and death [

6]. This critique is closely related to the discussion about old public health vs. new public health [

7]. In the wake of the Ottawa Charter, the aim of health promotion, according to Kickbush, was to combine a social determinants approach (the old public health) with a commitment to individual and community empowerment (the new public health), and these are the characteristics we have tried to operationalize with the set of five principles [

8]. During the 1990s and 2000s, it became even more apparent that the moralizing approaches did not provide the intended effects. At the same time, more focus was being placed on other health dimensions, such as quality of life, wellbeing, social capital, etc. Consequently, various alternative mindsets started to emerge, with terms such as empowerment [

9], salutogenesis [

10], health literacy [

11,

12], self-efficacy [

13] and action-competence [

14], which were slowly but surely establishing themselves as part of the professional vocabulary of health promotion.

The objectives of the present article are to describe the five health promotion principles, to present the research and development projects at SHPR that have been based on this set of principles and to discuss the experiences and results from implementing this set of health promotion principles in healthcare and prevention practices.

2. The Five Principles

In the following, we present each of the five health promotion principles separately. After each section, we present a few projects in which the particular principle is used prominently. We end each of the five sections with a brief discussion of the principle’s applicability.

The five principles have appeared previously in various forms in the health promotion literature. Our approach is, however, quite unique for two reasons: (1) We unite the principles in a coherent approach and (2) We use the principles within the whole spectrum of primary, secondary and tertiary prevention. To our knowledge and based on our review of the existing literature, this combined approach is unique.

2.1. A Broad and Positive Health Concept: Health Should be Considered Broadly and Not Merely as The Direct Opposite of Disease and Death. It Should also Embrace Dimensions of a Good Life and The Significance of Social Relations

Underlying this principle is the fundamental assumption that humans exist within, and are influenced by, their cultural, economic and social contexts. Contemporary health problems are therefore embedded in the societal structures that surround us. This means that lifestyle and its health-related consequences cannot be treated independently of living conditions, and that a given intervention must be directed towards both lifestyle and living conditions [

6].

Conceptualization of the “positive” stems from the World Health Organization‘s (WHO) well-recognized definition of health from 1947: “Health is a state of complete physical, social and mental wellbeing, and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.” This definition uses the concept of wellbeing to indicate the positive aspects of health. It is important to note, however, that WHO’s positive definition still includes absence of disease as one of the dimensions of health. The positive definition is, in other words, more extensive than the negative, which merely focuses on absence of disease, while still emphasizing the importance of avoiding illness.

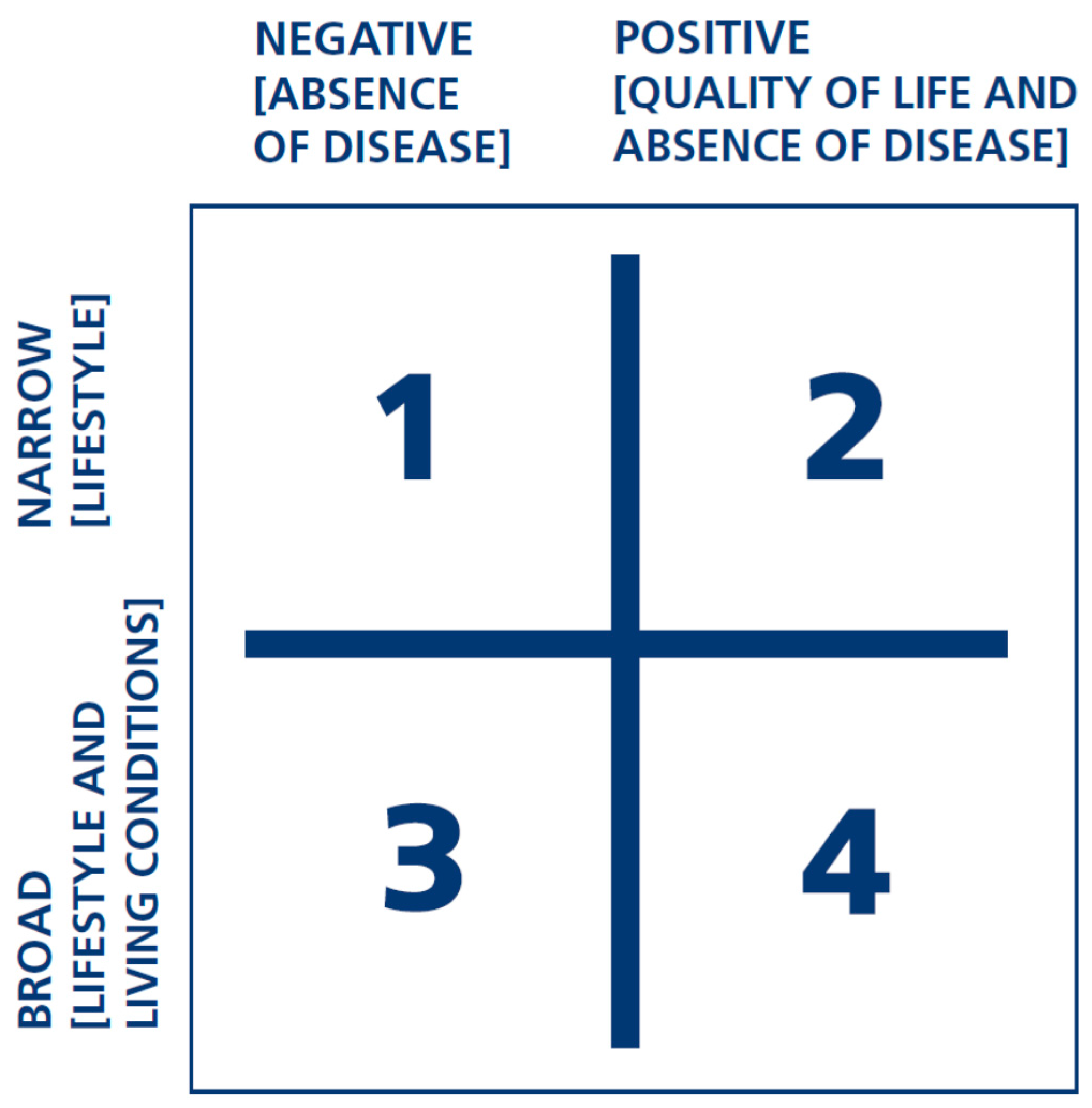

Figure 1 summarizes the definition of “positive” and “broad”, with the horizontal axis representing the difference between positive and negative and the vertical axis representing broad vs. narrow [

6]. The two concepts can be combined in four different ways, and the figure therefore illustrates four different possible health concepts. The SHPR approach strives for the health concept in square 4.

For example, a “positive” definition of health is applied in relation to food and meals when both the aesthetic and nutritional aspects are addressed. Working with a “broad” concept may include the availability of healthy food in the canteen, its cost, etc., as factors influencing attempts to motivate individuals to eat healthier.

The “positive” approach to the health concept relates to the target group’s everyday language and concepts. The terms “food” and “meals” generate more interest and engagement than do “nutrition” and “diet”. Similarly, “games”, “play” and “dance” ensure greater motivation in the target groups than do “physical activity” and “exercise”. Words and concepts are not neutral. They can exclude and demotivate, or they can contribute to ownership and internalization. Thus, a broad and positive concept of health is a determining element in attempts to engage and motivate the target group.

2.1.1. Selected Projects Prominently Guided by a Broad and Positive Health Concept

An illustrative example of our work with a broad and positive concept of health is a study investigating the non-biomedical dimensions of health among adults with type 1 diabetes. The study demonstrated that distress directly relating to life with diabetes and poor quality of life is highly prevalent among adults with type 1 diabetes. The study also demonstrated that low social support in everyday life with diabetes is associated with poor mental health [

15]. Furthermore, having fewer social contacts and lack of social support was associated with difficulties in diabetes self-management and higher blood sugar levels. The study thus clearly showed a relation between social, psychological and biomedical factors and pointed to peer support as a way of targeting this challenge [

16].

Another example is the PULSE project, which is a research collaboration between us and a Copenhagen-based science centre. The project’s vision is to involve families in creating innovative research-based science exhibitions and community activities that motivate and support families with children to take action to develop and sustain a healthy lifestyle. The research shows that many people associate physical activity with hard effort and guilt and see it as something that is incompatible with everyday life and family relations. Moreover, physical activity is viewed as a formal activity that usually takes place within certain frameworks, requires resources and is undertaken at the expense of more enjoyable activities. The broad and positive health concept, on the contrary, ensures that pursuing a healthy lifestyle is presented as enjoyable, fun and pleasant [

17,

18].

2.1.2. Brief Discussion

The concepts and approaches inspired by the broad and positive concept of health have been in high demand. For example, the studies of psychosocial aspects of diabetes previously mentioned led to a large amount of feedback from individuals with type 1 diabetes, who perceived them as an important acknowledgement of aspects other than the biomedical dimension. Based on SHPR research on health promotion in schools, the “broad and positive health concept” has proven to be a key for school practitioners’ understanding of the school as a health promotion setting. Teachers and school nurses state that students far too often associate health with something negative. Hence the broad and positive concept of health can play a valuable role in reaching out to, and encouraging participation among, children and young people who are disenfranchised in debates about health and wellbeing [

19].

The broad and positive concept of health can perhaps best be seen as an overriding premise or philosophy that requires a focus on dimensions other than the biomedical and/or disease-specific and that includes these in preventing diabetes and in relation to patient education and support. It guides the choice of theory and methods in the research undertaken by SHPR on a general level, albeit a broad and positive concept of health is only specified and operationalized by virtue of the specific research topic, theories and methods selected and our four other principles. This principle may be thought of as a concept that strengthens the other principles, but that would be incomplete if it stood alone. There is still work to be done to refine the broad and positive health concept. It is important to specify whether and how this positive health concept leads to a subjective approach to health. It is important to consider how broad a health concept should/can be without losing relevance and significance—and who should define the potential breadth?

Whether we are dealing with patients with type 1 diabetes, a group of citizens in a local community or children in health education classes, it is the emphasis on both social and mental aspects of health that ensures strong engagement and enhanced motivation—and improves the likelihood that participants will find the desire and willingness to make health related changes.

The challenge for future health promotion consists of illustrating and documenting how risk of disease and disease-related complications cannot be treated independently from psychological and social factors. A positive, general wellbeing-oriented approach should thus be viewed as a potentially productive way of lowering risk and preventing disease. On the other hand, it is important that the well-being component does not take over the agenda, thus reducing the potential for disease prevention.

2.2. Participation and Involvement: Participant Involvement Means Ensuring the Target Group’s Influence on Projects and Interventions

Participation and involvement is perhaps the most central of the health promotion principles, in the sense that sustainable health promotion change can only take place if the target group has the opportunity to develop ownership—and ownership and internalization are more likely to be achieved if the target group is actively involved in the processes from the start.

The notion of participation and involvement can imply many different things among different groups of healthcare professionals. This principle highlights the fact that development of ownership is not necessarily determined by those who take the initiative. The interesting developments may well first occur in the subsequent process, which leads to the point of decision-making. A situation in which the healthcare professional initiates a process by proposing a range of options, which are then developed and modified by the target group (e.g., patients), allows for greater involvement and strengthened ownership and empowerment. The focus for developing ownership thus shifts from “initiative” and “bottom-up” to “dialogue” and “co-creation”.

Hart notes that participation varies with individual characteristics and with context [

20]. People have different kinds of motivation, capacity and potential for participation [

20,

21]. It is therefore important to maximise the opportunity for anyone to choose to participate at the highest level of their ability.

There are often several stages involved in health-related projects. These stages further allow for different forms of participation, and therefore a given health project often covers many different forms of participation along the way. One question could be whether participation is voluntary, and a second could relate to who takes an active lead in developing visions, ideas and proposals for solutions. A third question could focus on who should be involved in evaluating and, if necessary, modifying the project for implementation in practice.

The principle of participation and involvement lies at the heart of diabetes prevention and management, as it places the responsibility for facilitation on the healthcare professional, whose task is to carry out an authentic dialogue with participants. During the course of this dialogue, it is both the right and the duty of healthcare professionals to contribute their professional knowledge, shape the dialogue and provide their own opinions. The dialogue must, however, facilitate discussion about mutual expectations and active participation in the decision-making process and ensure that it is mutually respected by the participant and healthcare professional. This health promotion principle thus signals a potential alternative pathway between top-down and bottom-up: dialogue and shared decision-making.

2.2.1. Selected Projects Prominently Guided by the Principle of Participation and Involvement

The IMOVE prevention programme was developed using participatory action research and combines mathematics and health education in teaching for Danish schoolchildren in grades 5–7, the aim being to develop pupils’ understanding of how to establish daily physical activity routines. The IMOVE research shows how the use of pedometers creates commitment and involvement amongst pupils, because recording and working on your own data is fun. The research also shows how IMOVE develops an understanding of how physical activity works and that it is not only when we engage in sports that we are active [

22].

EMMA (Empowerment, Motivation and Medical Adherence) is another example of a co-creation research and development project that addresses and supports participation. It consists of a collection of interactive dialogue tools developed for initiating patient participation in consultations between healthcare professionals and patients with poorly controlled type 2 diabetes. The aim is for patients to develop action competence and successful self-management and through this to achieve more stable glycaemic control. The dialogue tools consist of 24 visual health education exercises with pictures, quotations, questions, illustrations, icons and material for note taking. In every consultation, the dialogue tools are used as a basis for working together and co-creating solutions. The quantitative results of a pilot study showed that EMMA patients had better regulated diabetes than the control group did. The qualitative evaluation showed that, as intended, the dialogue tools generated and encouraged mutual participation [

23].

2.2.2. Brief Discussion

As a result of these and other projects, there is now a wealth of experience indicating that the principle of participation can assist in the development and implementation of tailored, and thereby sustainable, methods and tools, which can assist in creating increased action competency and health promoting practices among the target groups involved.

Many SHPR projects reveal that the principle of participation and involvement go hand in hand with the concept of positive and broad health. Articulating the possibility that health can also include social dimensions and a quality-of-life perspective paves the way for participation and involvement. This strengthens the development of motivation and ownership among different target groups and thereby paves the way for sustainable health change.

Even though the principle of participation and involvement can facilitate positive change, there are still challenges. The process of participation does not always lead to genuine participation by all target groups. This can result from the different preferences found in the target groups. The dialogue format may not appeal to certain individuals or groups who may feel uncomfortable contributing to setting the agenda and may feel that the physician or schoolteacher should decide what is important. In accordance with this, it is important to realize that some of the methods appeal particularly to target groups who are already comfortable with expressing their attitudes and beliefs. This could lead to the unintended risk of a fissure between the principle of participation and involvement and the principle of equity in health, as those who may need it the most are least likely get involved. For this reason, the projects target the application of different participation dynamics with respect to socially vulnerable or deprived social groups, such as individuals with a psychiatric illness or those who are at a high risk of developing diabetes.

2.3. Action and Action Competence: Participants are Given the Opportunity to Build Skills to Manage Their Own Lives and Change the Conditions and Structures that Influence Their Health

In SHPR projects the concept of action competence is an overall goal. The concept derives from an educational tradition based upon democracy, participation and a “hands-on” approach. This stands in contrast to the more behavioral tradition, where the goal is to shape individual behavior in a predetermined direction [

24]

A range of important health promotion concepts and approaches incorporate, in one way or another, a resource-oriented perspective on health issues. Attention has been directed towards, among other things, the five components described below. Collectively, these components constitute the elements necessary to achieve a high level of what we choose to call “action competence”.

Insight: A broad, positive and action-oriented understanding of health, including insight into effects, causes and change strategies within the health area.

Commitment: The desire and motivation to get involved in change processes with a view to promoting health.

Vision: The ability to think creatively and have a vision, while allowing oneself to be inspired by other scenarios.

Action experience: Experience of undertaking change processes at both individual and collective levels, including tackling and overcoming any barriers.

Critical sense: The ability to critically question information before adopting and drawing reasonable conclusions.

Action experience—i.e. direct experience with changing one’s own life or surroundings—constitutes a core element of “action competence”. A health promotion approach aimed at building up action competence should therefore allow target groups to be involved with authentic issues and challenges in order to utilize the learning potential found in real-life actions.

“Action competence” and “action” are inter-related, but should not be confused with each other. For example, a group of children may possess the ability to act (action competence) in the context of “body and motion”, but they also require an opportunity to apply the competence in order to achieve a health-related change. In other words, there should be sufficient “room for action”, such that the developed “action competence” can unfold. Accordingly, the healthcare professional should provide space and foster the target group’s action competence. The concept of action competence is closely inter-linked with a focus on settings and enables us to look at how living conditions influence the ability to facilitate the components of action competence.

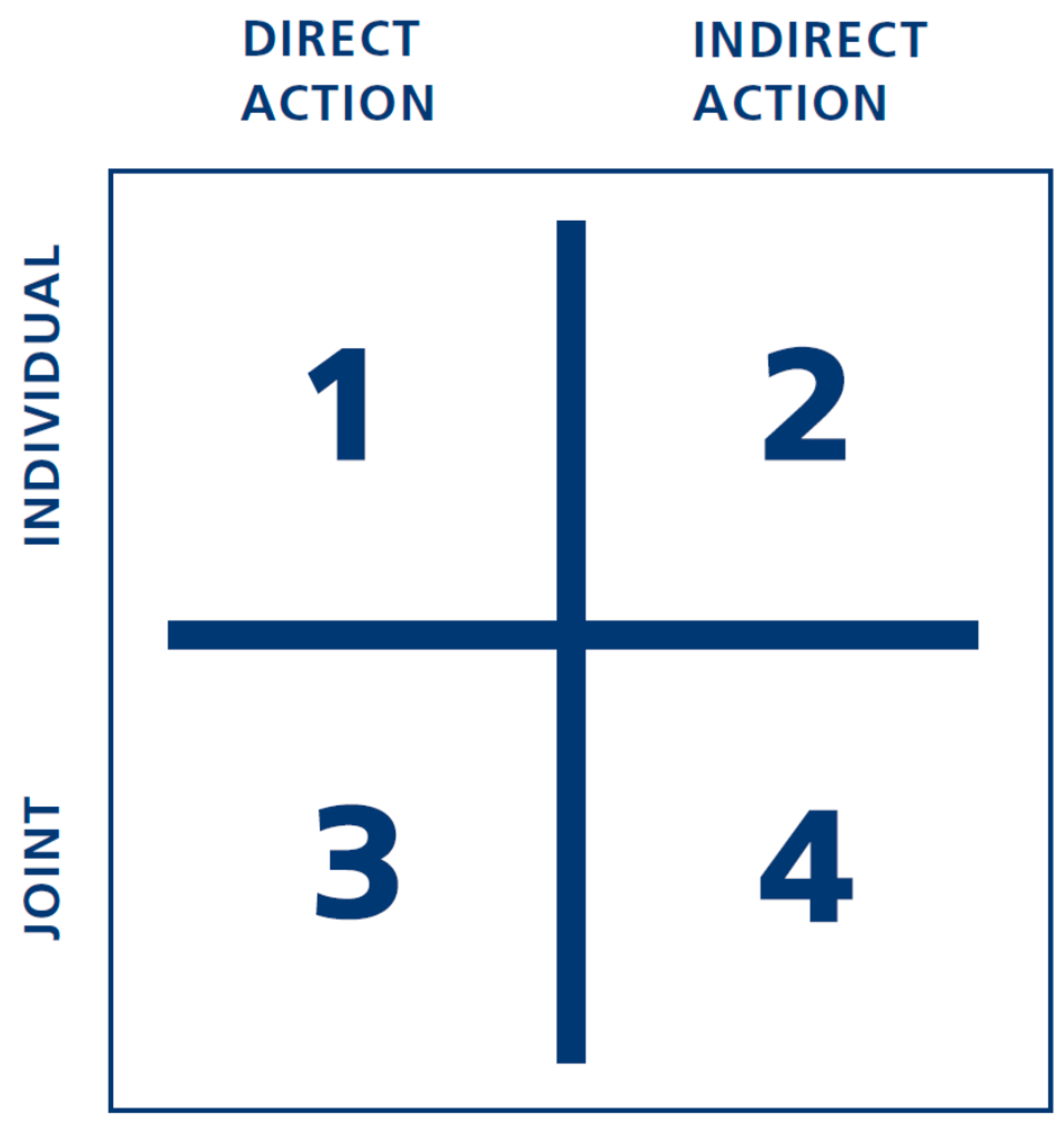

Figure 2 can be used to systematize opportunities for action with regards to the existing health problem. The figure highlights the fact that individuals can act alone or collectively as a group. Furthermore, the action can be direct (e.g., by trying to change their own behaviour) or indirect, targeting structural components in the given setting (e.g., by changing the opportunities for exercise in their local area or at work). Thus, the figure provides four different forms of action for change, all of which should be examined and considered when a particular target group is working with a given health problem.

To illustrate the figure’s applicability, it can be said that efforts to change people’s eating habits are placed in square 1, while a situation in which patients are seeking inspiration and support from other patients for maintaining a healthy lifestyle belong in square 3. Square 4 characterizes a form of “action” where patients jointly try to influence the general context of their daily lives, for example by creating an opportunity to take exercise in their local community or their workplace.

The figure has been directly applied in health processes with participants, in conjunction with professionals, for brainstorming to provide as many opportunities “to act” as possible in each of the four squares for the given health-related issue. This could, for example, be done with respect to physical activity and exercise, where employees at the workplace make suggestions for their own exercises, which could be carried out during their break. Alternatively, it could also lead to ideas for environmental restructuring in a workplace, nurturing opportunities for enhancing movement.

While developing new interventions, it is important to bear in mind both dimensions of the model to encourage individuals to take action regarding their own health and also to facilitate social actions to improve the environment in which they live.

2.3.1. Selected Projects Prominently Guided by the Principle of Action and Action Competence

NEED (NExt EDucation) is a concept for interactive teaching including dialogue tools developed together with healthcare professionals and people with type 2 diabetes for use in group-based patient education for people with type 2 diabetes and other chronic diseases. NEED can be used in both the primary care setting and the hospital setting. The aim of NEED is to support an interactive, participant-oriented formal teaching programme that boosts participants’ action competence and empowerment, including how to take good care of the diabetes and still achieve good quality of life. Participants are asked to identify opportunities and barriers and supported in prioritizing, addressing and setting goals related to their personal cultural and psychosocial needs. This allows for increased awareness of their own goals and values and further motivates them to make suitable plans for and decisions on how to live with diabetes [

25,

26].

Developed as a part of NEED, the model “The Health Education Juggler” elaborates on the skills that healthcare professionals need to possess in order to support patients during a process in which they create a balanced way to live with chronic disease. The healthcare professional needs to master four roles in this relationship: (1) Embracer—respects and accepts everyone in the group unconditionally; (2) Facilitator—enabling processes without restricting the content; (3) Translator—translating questions, reflections and discussions into factual diseaseor behaviour-specific knowledge when appropriate; and (4) Initiator—exploring readiness to change and guiding towards reflection and useful action. Healthcare professionals are regarded as health education mediators who have to juggle four different roles in order to meet the needs of patients [

27].

2.3.2. Brief Discussion

Our research indicates that, in order to work systematically and explicitly towards developing action competence in different target groups, there are specific requirements for professionals, e.g., healthcare professionals, teachers, educators. The challenge for future educational efforts is not solely to develop the action competence of target groups, but, equally importantly, to use the already existing ideas and competencies of the target groups as a starting point to ensure that these competences are taken into account to bring about the necessary scope for action. Professionals, including the management of the institution concerned (school, workplace, clinic, etc.), have an equally important role to play.

Several SHPR projects have sought to capture and measure the concept, for example the IMOVE project, which is focused upon pupils’ action competence with respect to exercise and physical activity. In other projects the focus has been on how action competence supports patients or other relevant target groups in taking control of their own lives. The mechanisms for developing action competence, as it has been integrated into SHPR tools and methods, relate particularly to the first two principles, namely involvement of the target group through a positive and broad approach to health, in an everyday-life perspective.

A future challenge concerns the question of how to prevent action-oriented approaches from falling into the “individualistic trap”, as the core element of the action competence concept is to be able to focus on the individual in his or her unique context without generating negative individualizing mechanisms that are often seen within the more moralizing frameworks. There is, therefore, a great demand for developing systematic approaches and tools that enable the potential of individuals to support each other (peer support) and to collaborate collectively in the prevention and management of diabetes.

2.4. Health Should be Viewed from a “Settings Perspective”: The Structural and Contextual Settings in Which People Live, Work and Reside Influence Their Opportunities for Healthy Living

Health education cannot stand alone. Our lives and practices are influenced by the general contextual framework in which we live. The underlying aim of always applying a settings perspective is that a given intervention should encompass educational components as well as the surrounding contextual framework within which education operates.

Examples of frameworks that should be included in health promotion could include environmental restructuring in different settings, e.g., the school classroom, the preschool playground, the local community centre, the physical and aesthetic environment of the clinic or the training rooms at a municipal prevention centre.

It is possible to differentiate between two different varieties of the setting concept: (1) The immediate context within which teaching or interventions occur (e.g. school, clinic, prevention centre or workplace) and (2) the context within which participants’ daily lives unfold (e.g. home, local area or sport clubs).

Context, as applied in the first sense here concerns the physical, cultural and social frameworks for conducting the intervention, whereas in the second sense it relates to the framework of a daily life within which learning has to be applied.

Here it is essential to focus on how physical and social structural frameworks provide optimal synergy for health promotion issues. For example, one could address how the immediate physical environment should be restructured to allow greater opportunity and motivation to encourage participants to share their experiences. For instance, does placing tables and chairs in a certain way have an effect on participation and motivation? What environmental conditions assist in creating a pleasant atmosphere that has a positive influence on motivation? How should the physical surroundings be organized to provide optimal desire to exercise among people attending a municipal prevention centre?

2.4.1. Selected Projects Prominently Guided by the Settings Perspective

SoL is a health promotion research and development project carried out in selected local communities in the Danish municipalities of Bornholm and Odsherred. The aim of the project is to promote the health and well-being of families with children by influencing their shopping, eating and exercise habits and by mobilizing the resources of the local community and strengthening its social cohesion. The key innovative aspect of Project SoL is that health promotion activities are developed and implemented locally and integrated across such settings as childcare centres, primary schools and supermarkets, but also in public spaces such as town squares and recreational areas. This results in broad participation, synergy and optimized utilization of local resources. The geographical target area for Project SoL’s interventions in the local community is called a supersetting, and the applied approach, facilitating joint collaboration among different settings, is called a “supersetting approach” [

28].

In the PIFT project, the focus is on the family as a key health promotion setting. Through an extensive design-based research process that included needs assessment workshops, ideation workshops and prototype testing, we have (together with families and healthcare professionals) developed a family toolkit that aims at addressing familial barriers to mutual involvement, prevention and early diagnosis in families living with type 2 diabetes. The needs assessment showed us that the family dynamics in these families are complex and often severely negatively affected when a family member is diagnosed with type 2 diabetes. The toolkit is designed to address six specific domains of intra-familial problems or challenges: doubts about knowledge, inadequate communication, role confusion, frustrations with everyday life, misunderstood/unhelpful support and mutual worries. In PIFT we have also created a programme for development of healthcare professionals’ competencies to work with family involvement in general and with the family toolkit in particular [

29,

30].

2.4.2. Brief Discussion

SHPR research has qualified the multi-faceted orientation of the setting approach with its special emphasis on patient-centred environments and citizen-centred local and social environments. We have further demonstrated how setting as a concept, principle and value influences the research subject, design and choice of analytical approach for our projects.

For diabetes management and prevention research, the setting approach provides a view of life as it is actually lived, whether this relates to work, the family or the local community. It also sharpens the focus on the complexity associated with health promotion initiatives. While other approaches to research seek to avoid or remove the complexity of daily lives by choice of study design or analytical methods, the supersetting approach welcomes complexity and seeks to actively handle, describe and modify it.

This gives rise to challenging methodological discussions. The rationale underlying the setting concept is non-medical, and it therefore requires translation to work with the concept in the more medical and traditional evidence-oriented context that dominates health and diabetes research. This paves the way for a discussion on how research into social, complex and context-specific issues can supplement traditional research in the field of health and diabetes. Accordingly, there is a need to discuss how to operationalize health promotion, for example in the workplace, the family or the local community.

2.5. Equity in Health: Not Everyone has the Same Opportunities for Leading Healthy Lives and Changing Practices. Health Promotion Interventions Must Take These Differences into Account

This fifth principle, which aims to increase equity in health, is strictly speaking not a methodological principle in the same sense as the four other principles. Rather, it is an ideological perspective and a core value that all projects and all of the other four principles should take into account.

There is no doubt that individuals from socially disadvantaged groups have a higher risk of developing chronic conditions such as type 2 diabetes [

31,

32]. It is also well known that practically all methods used in diabetes management and prevention are less effective in individuals who have access to fewer resources [

33]. In other words, there is a need to direct our attention towards those who are most vulnerable and to try to understand how they can be motivated and involved as effectively as other groups.

The fifth principle therefore focuses on developing and designing tailored methods and approaches that fulfil the unmet needs of specific groups, such as residents in certain socially disadvantaged areas, or vulnerable individuals with diabetes, e.g., from ethnic minority groups or people with multi-morbidity. Moreover, this perspective also encompasses a leading global challenge that demands immediate attention in areas of the world suffering from major health-related social and financial burdens and, thus, requires effective interventions for both prevention and patient education.

For diabetes prevention and management research, the setting approach provides a view of life as it is actually lived, whether this relates to work, the family or the local community. It also sharpens the focus on the complexity associated with health promotion initiatives. Whilst other approaches to research seek to avoid or reduce the complexity of daily lives by choice of more positivist study designs or analytical methods, the setting approach welcomes complexity and seeks to actively handle it, describe it and intervene.

The underlying idea behind integrating this principle into an intervention paradigm with the four other principles is that those who have limited resources and are marginalized and vulnerable are expected to gain equally from a participant-oriented, skills-enhancing approach based on a positive, broad concept of health. However, the principles should be modified and applied in line with the actual resources available to specific target groups within their local contexts.

2.5.1. Selected Projects Prominently Guided by the Principle of Equity in Health

Patient education is a good example of a concrete healthcare action taken to counter inequity in health. In a co-creation project focusing on helping vulnerable patients learn how to live better, more healthy lives with diabetes, we have created a toolkit with nine health education tools enabling (healthcare) professionals to reach more vulnerable patients in a positive and constructive way. The approach addresses the challenges that these hardly reached patients face in relation to general patient education programmes and the challenges educators face when conducting patient education with hardly reached patients. In a qualitative study we identified four main categories of preferences for patient education that reaches out to these groups of patients: (1) flexibility related to start time, duration, and intensity; (2) simple and concrete education tools, with regard to design and extent; (3) being together, related to meeting people in a similar situation; and (4) respectful educators, related to constructive patient–educator relationships [

33,

34].

In a recent and as yet unpublished project in the socially deprived area of Tingbjerg in Copenhagen, we emphasize the social dimension of preventing and managing type 2 diabetes. The projects aims at reducing inequality by establishing a long-term intersectoral partnership between diverse professional stakeholders who are dedicated to engaging with residents in participatory processes of defining, planning, implementing and evaluating actions that target people's well-being, social capital, self-efficacy, health literacy, food literacy and physical activity. The project is based on the values and principles of the supersetting approach [

23]. The cornerstone of action and change is the social development plan of the neighbourhood and the area secretariat established to implement it. The area secretariat is a gatekeeper to informal social networks in the neighbourhood and has a wealth of experience in how to manoeuvre in socially vulnerable environments and how to establish respectful relations with residents. The intervention is therefore carried out outside the framework of the traditional health system in the community.

2.5.2. Brief Discussion

The nature of the final principle, increased equity in health, differs slightly from the other four principles. It constitutes a normative and value-based statement-of-intent that SHPR has focused specifically on, through research and development, by targeting our interventions towards marginalized groups that have few resources.

Our projects have addressed two different issues in relation to this principle. The first example focuses on developing and testing interventions that appeal in particular to socially disadvantaged groups, e.g. patient groups, whereas the second example explores how socially marginalized communities can be engaged in collective health-promoting activities. A review of the literature indicates that both of these areas are poorly explored and researched, and new and innovative approaches are therefore needed.

In our future research, special attention will be paid to trying to understand how methods and tools should be tested and developed for creating equity in diabetes prevention and patient education. This must be done in close collaboration with representatives from vulnerable or socioeconomically disadvantaged groups in a “co-creation” process. What are the special requirements for researchers and research methods when partners come from these groups? What competencies are required from healthcare professionals when using methods and tools together with vulnerable groups? And what kinds of diversity should the health education juggler be able to cope with?

3. General Discussion

Above we have described SHPR’s five principles, a series of projects guided by these principles and some thoughts on the applicability of the principles in research and practice. The principled approach enables us to consolidate hitherto disparate approaches into one comprehensive perspective. This relates to health promotion, diabetes prevention, diabetes management, treatment and early diagnosis and more generally to the areas of primary, secondary and tertiary prevention.

On the one hand, we acknowledge that health promotion, disease prevention and disease management have different objectives as well as different target groups. On the other hand, interventions and activities from the whole range of primary, secondary and tertiary prevention will benefit from the approach described by the five principles presented here. For example, the concept of dialogue-centred participation (defined as neither top-down nor bottom-up) opens doors to innovative strategies for the entire healthcare sector. Similarly, the setting principle makes it possible to link structural prevention and the concept of “nudging” to educational interventions and skills-enhancing development in the target group. For example, an approach consisting of access to a healthy range of food in the canteen at the workplace combined with the development of health-related action competence among staff members will increase the likelihood of generating synergy between the different interventions.

The most important lesson from the projects is that even though the five principles can be described independently, they are in reality strongly interconnected. For example, involvement and participation are prerequisites for working with a positive concept of health that is rooted in day-to-day values. Conversely, it is necessary for individuals to participate if we are to understand what health means to them and how it is related to their overall priorities. Furthermore, participation and involvement can be seen as important springboards for ensuring that patients have developed the skills and competencies to manage their own lives with diabetes. Action competence and empowerment are developed through real-life action.

This inherent focus on always securing the appropriate level of participation and involvement have helped us overcome the risk, described by, among others, Petraglia [

35] and Piko and Bak [

36], of not making interventions and health communications sufficiently relevant for the target groups to relate them actively to their own perceptions of health. The perpetual risk of exclusively reaching the people who are already being reached by other health interventions and campaigns [

37,

38] has been an active concern in many of our projects. This is, however, where the fifth principle of equity in health really makes a difference by always reminding us that, no matter what we do, we should always focus on not running the risk of making the difference between the healthy and the unhealthy greater than it already is.

Looking at the output of our projects through Nutbeam’s [

39] lens of discerning between health promotion actions, health promotion outcomes, intermediate outcomes and health and social outcomes, it is clear that our focus areas can cover the whole spectrum of possible outcomes. Being intensely focused on the broad and positive concept of health and on equality in health, most of our projects focus on positive health and social outcomes as the end goal. The intermediate outcomes like healthy lifestyles and healthy environments are also addressed continuously through our principles on action competence and settings. The more immediate results of planned health promotion activities and interventions are addressed in our projects by paying direct attention to concepts like self-efficacy and health literacy and through a general focus on improved health knowledge and motivation. Even more concrete is our involvement in health promotion actions like facilitation and education to motivate individuals and communities to act to improve and protect their health.

It is one thing to do innovative research and develop new approaches—it is something quite different to implement these innovations in healthcare practice in a sustainable way. Implementation science has progressed towards the increased use of theoretical approaches to provide a better understanding of, and explanations for, how and why implementation succeeds or fails [

40]. Contemporary implementation research furthermore seeks to understand and work within real-world conditions, rather than trying to control for these conditions or to remove their influence as causal effects [

41]. Our principled focus on settings has meant that we have an inherent focus on securing successful implementation of research results and interventions. This is, however, an aspect where we potentially could improve our efforts by more directly linking the set of principles to current implementation research [

40,

41].

All of SHPR’s projects are related to diabetes in one way or the other. Nevertheless, we contend that the findings and outcomes have a much broader relevance, as we have experienced that diabetes is suitable as a “model disease”, illustrating many dilemmas and potentials for health promotion and prevention in more general terms. The projects dealing with primary prevention for instance in schools has a comprehensive approach to healthy living within salutogenic environments. The diabetes management projects have garnered interest from healthcare practitioners working with other chronic diseases—as the methods and tools often address general dynamics and challenges when dealing with ill health.

Another important consideration is whether these predominantly Danish projects are transferable to other countries. The setting principle tells us that all projects have to be viewed exclusively within the unique context in which they are conducted - and that no project can be expected to work in exactly the same way when transferred to a different context. This means that every “new” context with its ensuing barriers and potentials for implementation has to be studied closely before transferring any project, method or tool. However, we contend that three of the principles especially (broad and positive concept of health, participation and setting), when taken seriously, will ensure that the principled approach is applicable more globally.

During the first seven years, our research has been characterized by approaches inspired by co-creation and action research [

42,

43]. We are continuously in partnerships with various collaborators (hospitals, local authorities, schools, etc.) that are in the process of identifying relevant problems and ways to resolve them. This approach means that researchers are in perpetual dialogue with the target groups, which leads to completely unforeseen developments and discoveries.

During this first period, we have systematically endeavoured to test the five intervention principles. This was done both separately and (for the most part) with more principles as drivers in individual projects. The principles have turned out to be productive “management tools” that have led us to new discoveries and have helped us to identify limitations. Our task for the coming five-year period will be to systematically address the dilemmas and challenges associated with developing effective, innovative and sustainable approaches to tackling the growing challenge of diabetes.