Decision-Making Behaviour under the Mental Health Act 1983 and Its Impact on Mental Health Tribunals: An English Perspective

Abstract

:1. Introduction

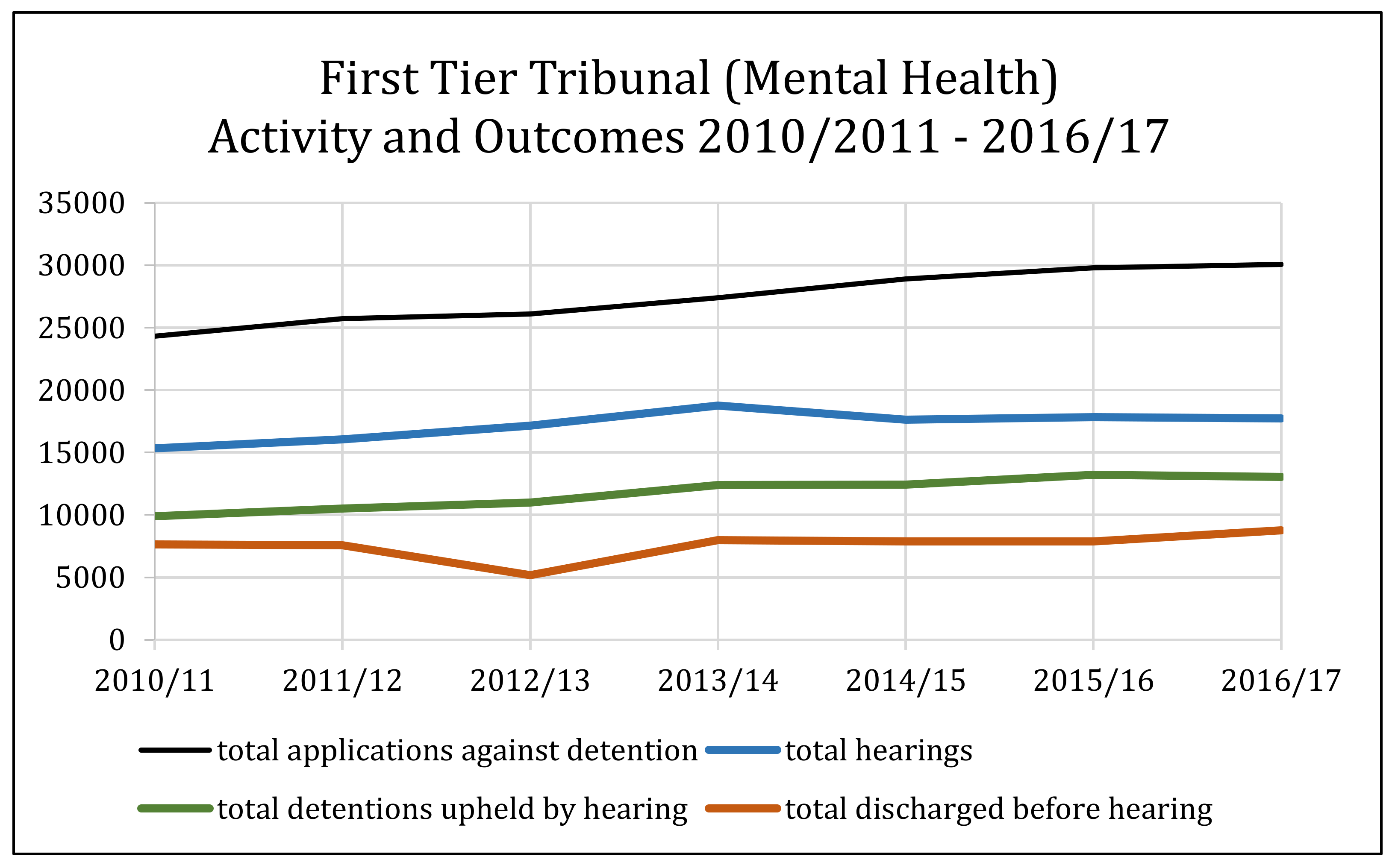

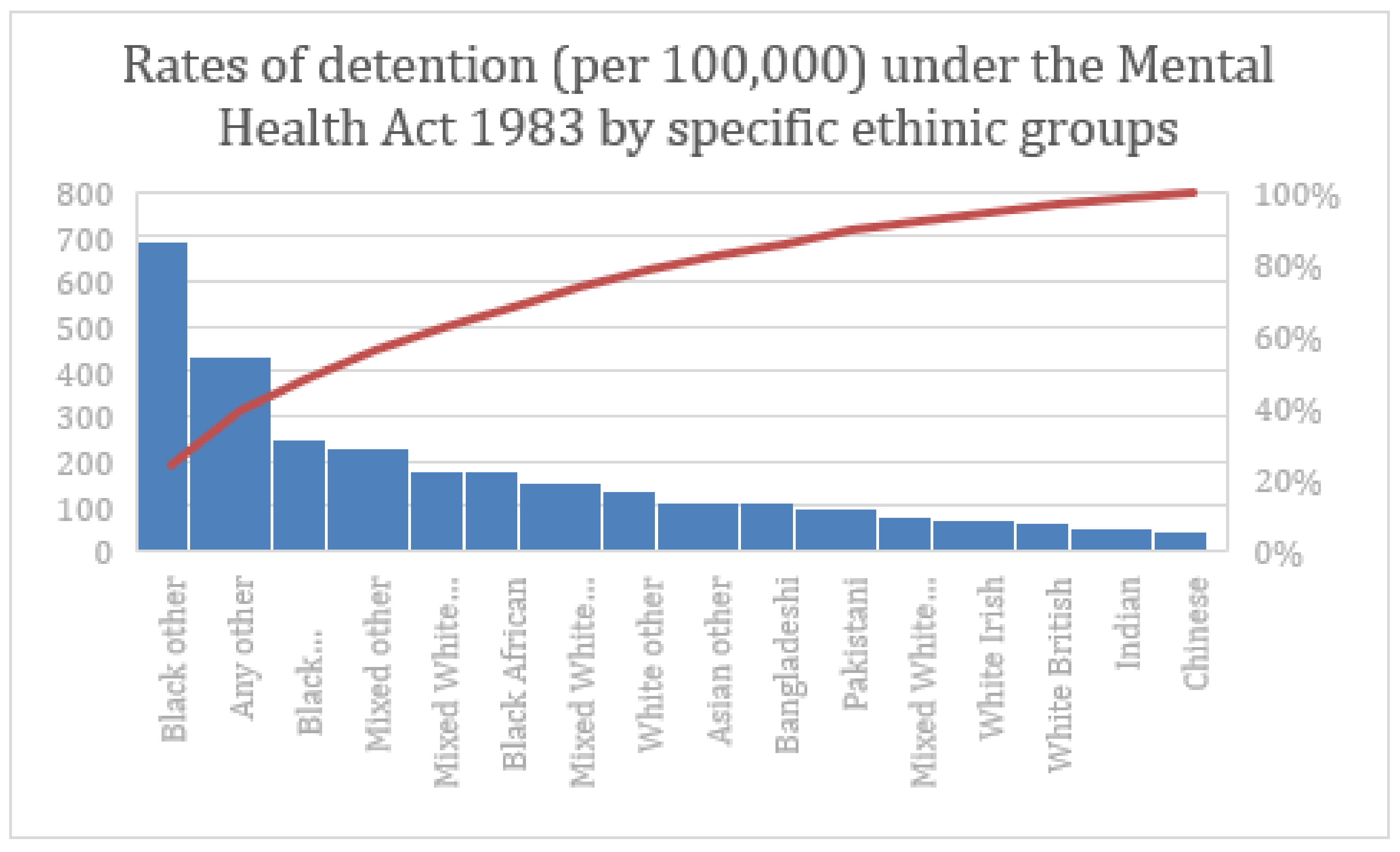

2. Mental Health Tribunals

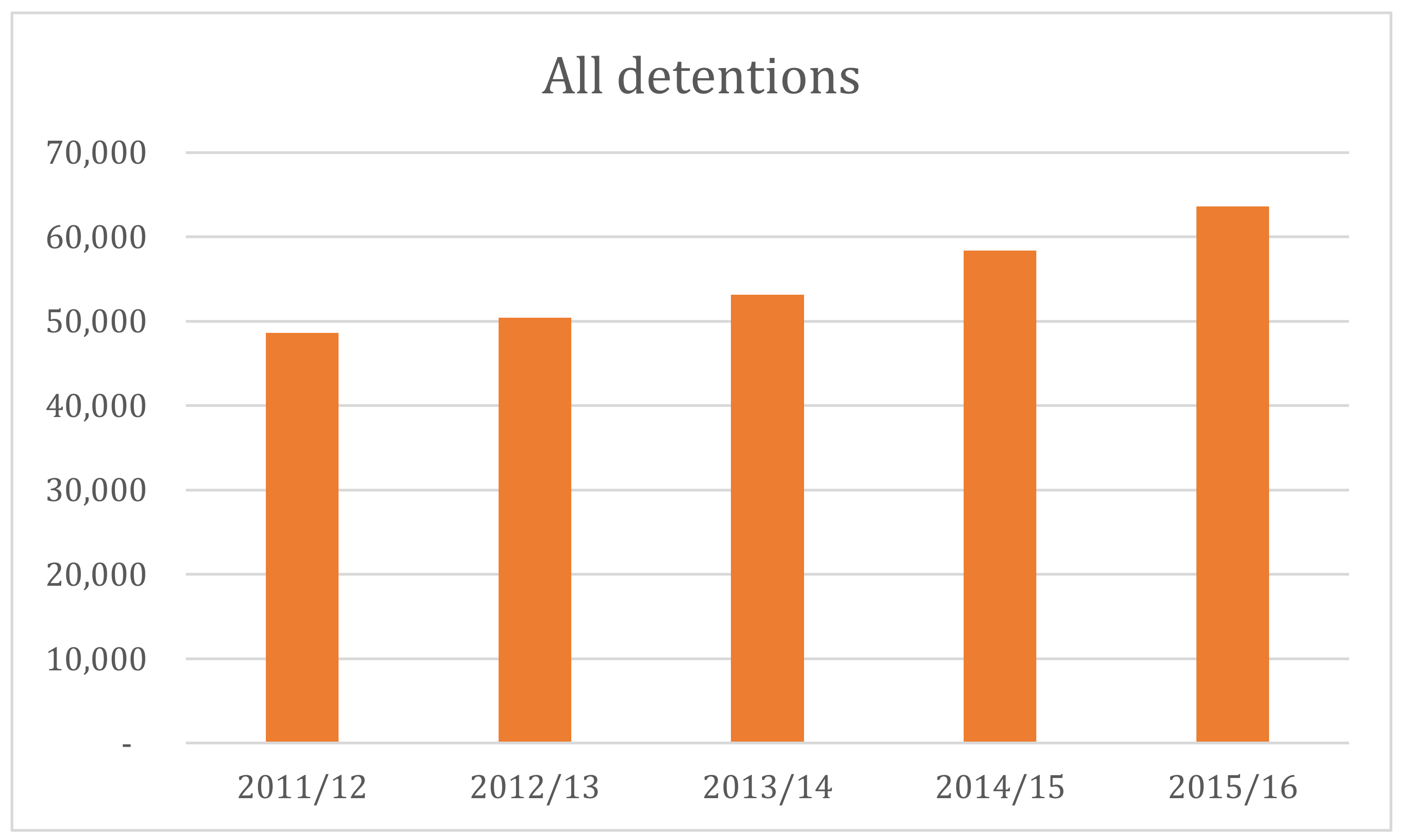

3. Detention Rates under the Mental Health Act 1983

3.1. A System under Strain?

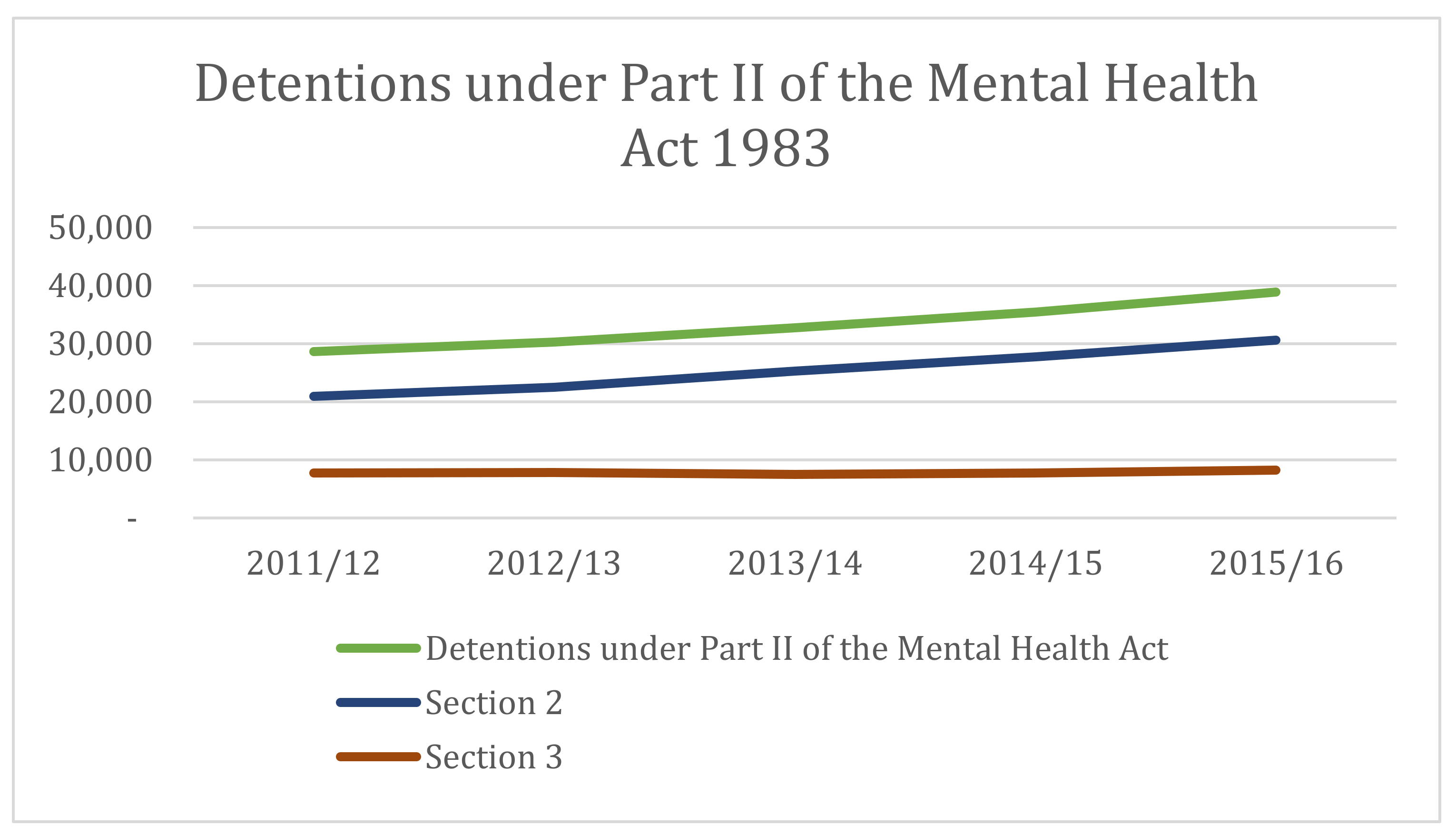

3.2. Rising Use of Section 2

- (a)

- he is suffering from mental disorder of a nature or degree which warrants the detention of the patient in a hospital for assessment (or for assessment followed by medical treatment) for at least a limited period; and

- (b)

- he ought to be so detained in the interests of his own health or safety or with a view to the protection of other persons.

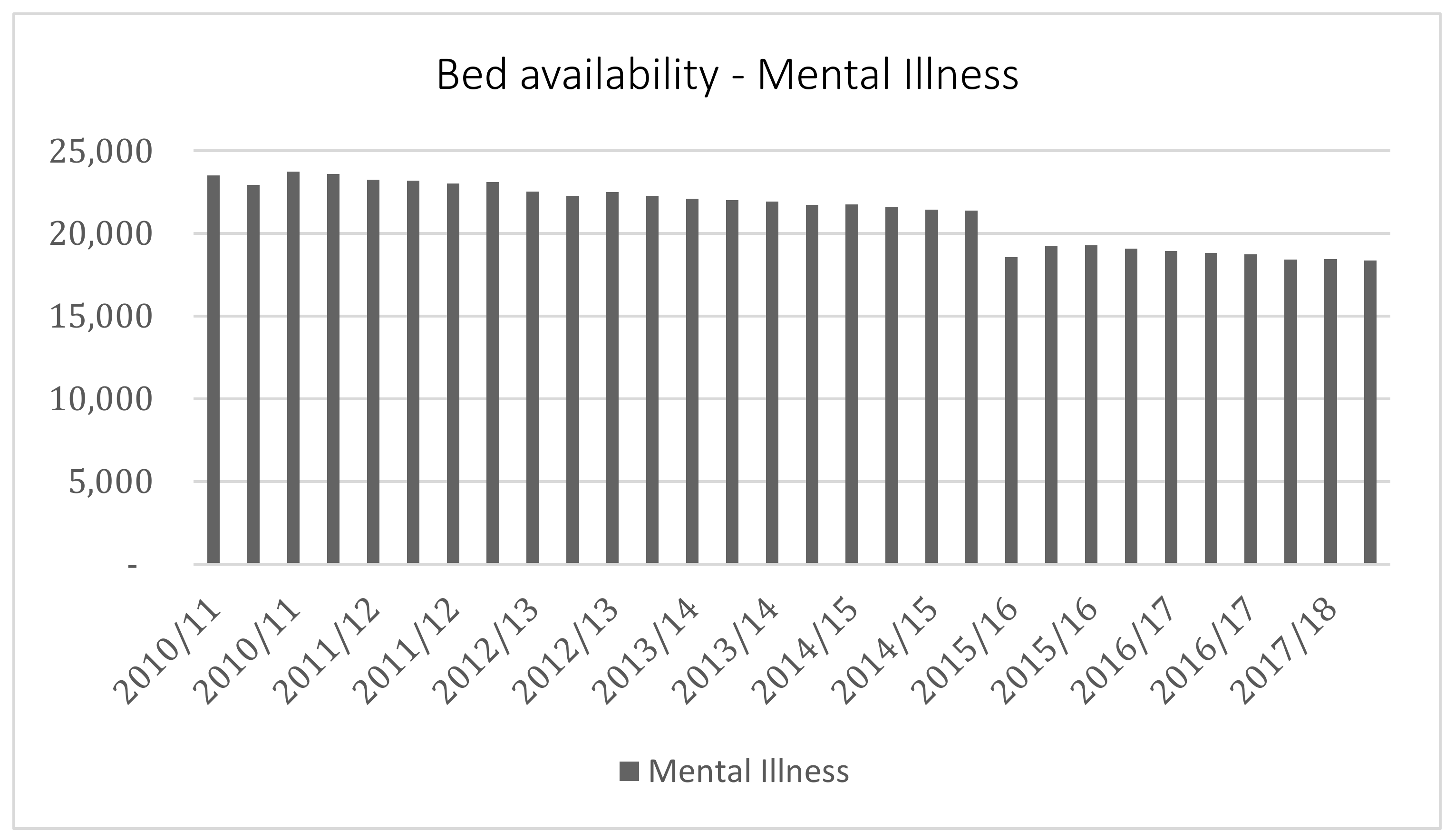

3.3. Declining Community Support and Its Impact

3.4. The Cheshire West Effect (and Other Cases)

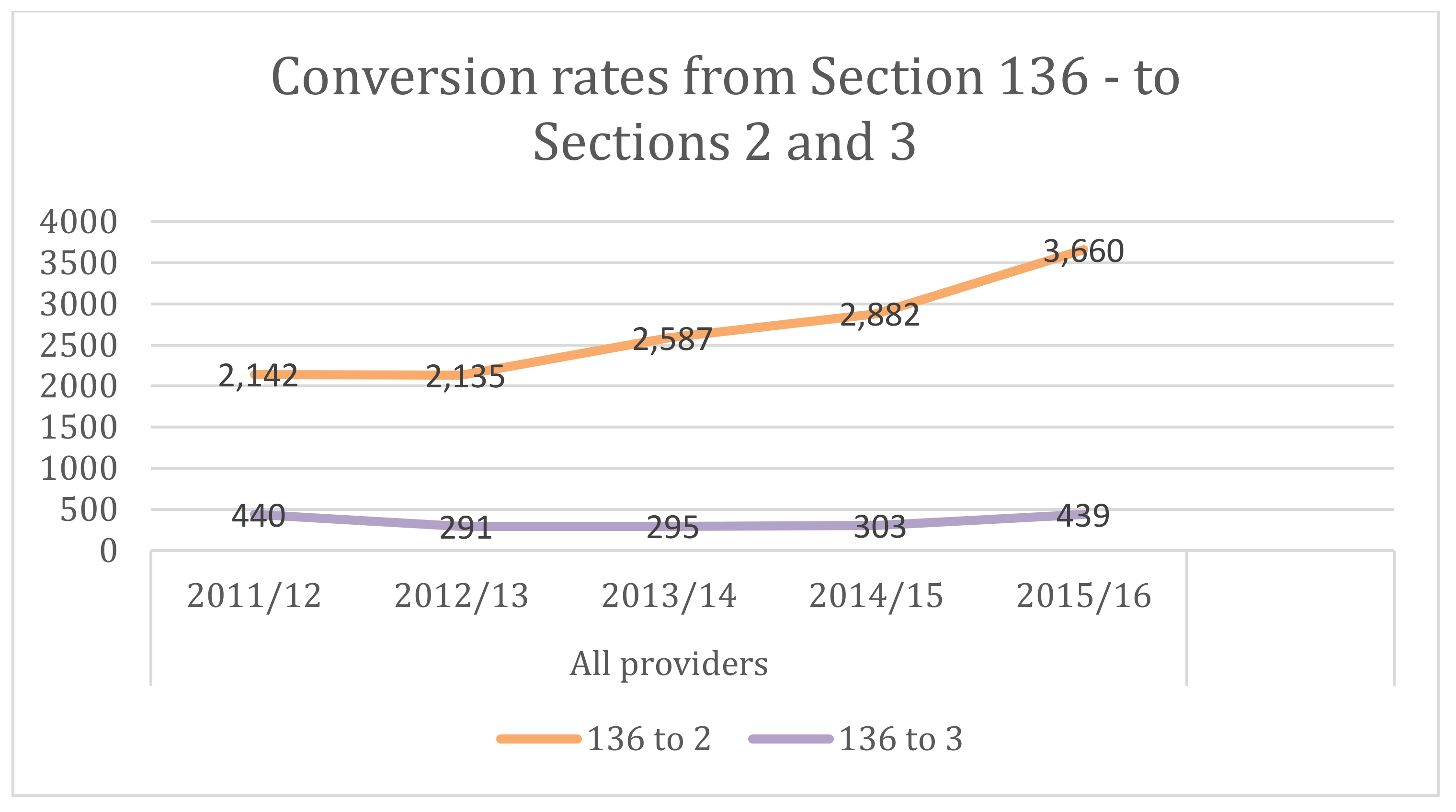

3.5. The Rise in Section 136 Use

3.6. Can Detention Rates Be Reduced?

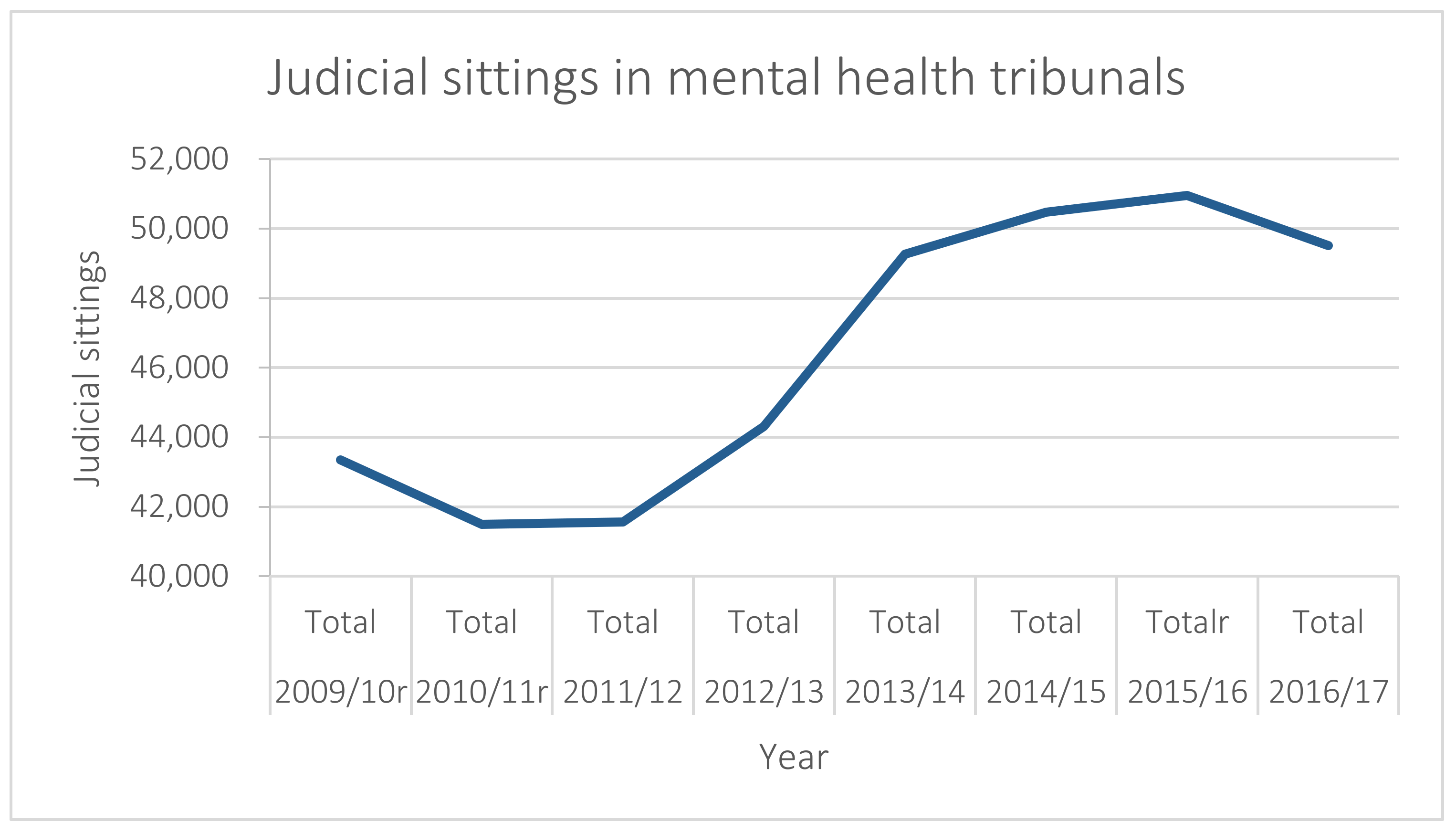

4. Mental Health Tribunal Caseloads

4.1. The Patient Voice

4.2. The Role of Independent Mental Health Advocacy

4.3. Mental Health Tribunal Delays

4.4. Other Challenges

5. Next Steps for Mental Health Tribunals

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References and Notes

- Allen, Neil. 2013. The right to life in a suicidal state. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 36: 350–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allmark, Peter, Baxter Susan, Goyder Elizabeth, Guillaume Louise, and Crofton-Martin Gerard. 2013. Assessing the health benefits of advice services: Using research evidence and logic model methods to explore complex pathways. Health & Social Care in the Community 21: 59–68. [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett, Peter. 2010. Civil Confinement. In Principles of Mental Health Law. Edited by Jean McHale and Judy Laing. Oxford: OUP. [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett, Peter, Thorold Oliver, and Lewis Oliver. 2007. Mental Disability and the European Convention on Human Rights. Leiden: Martinus Nijhoff. [Google Scholar]

- Blumenthal, Stephen, and Simon Wessely. 1994. The pattern of delays in Mental Health Review Tribunals. Psychiatric Bulletin 18: 398–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borschmann, Rohan D., Steven Gillard, Kati Turner, Mary Chambers, and Ann O’Brien. 2010. Section 136 of the Mental Health Act: A new literature review. Medicine, Science and the Law 50: 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burns, Tom, Rugkasa Jorun, and Molodynshi Andrew. 2008. The Oxford Community Treatment Order Evaluation Trial (OCTET). Royal College of Psychiatrists 32: 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Care Quality Commission. 2011. Patients’ Experiences of the First-Tier Tribunal (Mental Health) Report of a Joint Pilot Project of the Administrative Justice and Tribunals Council and the Care Quality Commission. London: CQC. [Google Scholar]

- Care Quality Commission. 2015. Right Here Right Now: People’s Experiences of Help, Care and Support during a Mental Health Crisis. London: CQC. [Google Scholar]

- Care Quality Commission. 2016. Monitoring the Mental Health Act in 2015/16. London: CQC. [Google Scholar]

- Castel, Robert. 1991. From Dangerousness to Risk. In The Foucault Effect: Studies in Governmentality. Edited by Burchell Graham, Gordon Colin and Miller Peter. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Coulter, Angela, and Ellins Jo. 2007. Effectiveness of strategies for informing, educating, and involving patients. British Medical Journal 335: 24–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawson, John. 2005. Community Treatment Orders: International Comparisons. Dunedin: Otago University Print. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson, John. 2010. Supervised Community Treatment Orders. In Principles of Mental Health Law and Policy. Edited by Jean McHale and Judy Laing. Oxford: OUP. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Constitutional Affairs. 2004. Transforming Public Services: Complaints, Redress and Tribunals; Cmnd.6243; London: TSO.

- Department of Health. 1982. White Paper on Reform of Mental Health Legislation; London: TSO, Cmnd 8405.

- Department of Health. 2011. No Health without Mental Health: A Cross-Government Mental Health Outcomes Strategy for People of All Age; London: HM Government/Department of Health.

- Department of Health. 2012. Post-Legislative Assessment of the Mental Health Act 2007: Memorandum to the Health Committee of the House of Commons; London: TSO, Cm 8408.

- Department of Health. 2015. Mental Health Act Code of Practice; London: Department of Health.

- Department of Health, and Social Care. 2013. Section 67 of the Mental Health Act 1983 References by the Secretary of State for Health to the First-tier Tribunal; London: TSO.

- Dineage, Caroline. 2018. Final Government Response to the Law Commission’s Review of Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards and Mental Capacity; Written Ministerial Statement, HCWS542; London: Houses of Parliament, March 14.

- Eades, Susan. 2018. Impact evaluation of an Independent Mental Health Advocacy (IMHA) service in a high secure hospital: A co-produced survey measuring self-reported changes to patient self-determination. Mental Health and Social Inclusion 22: 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firn, Mike, Keelyjo Hindhaugh, Dieneke Hubbeling, Gwyn Davies, Ben Jones, and Sarah White. 2013. A dismantling study of assertive outreach services: Comparing activity and outcomes following replacement with the FACT model. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 48: 997–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freckleton, Ian. 2003. Mental Health Review Tribunal Decision-making: A Therapeutic Jurisprudence Lens. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law 10: 44–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, Melvin, Kolappa Kavitha, Caldas de Almeida Jose Miguel, Kleinman Arthur, Makhashvili Nino, Phakathi Sifiso, Saraceno Benedetto, and Thornicroft Graham. 2015. Reversing hard won victories in the name of human rights: A critique of the General Comment on Article 12 of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Lancet Psychiatry 2: 844–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glover, Nicola. 1999. Mental health and housing: A crisis on the streets? Journal of Social Welfare and Family Law 21: 327–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glover-Thomas, Nicola. 2011. The Age of Risk: Risk Perception and Determination following the Mental Health Act 2007. Medical Law Review 19: 581–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glover-Thomas, Nicola. 2013. The Health and Social Care Act 2012: The emergence of equal treatment for mental health care or another false dawn? Medical Law International 13: 279–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glover-Thomas, Nicola, and Warren Barr. 2008. Re-examining the Benefits of Charitable Involvement in Housing the Mentally Vulnerable. Northern Ireland Legal Quarterly 59: 177–200. [Google Scholar]

- Grann, Martin. 2005. Psychiatric Risk Assessment Methods: Are Violent Acts Predictable? A Systematic Review (Summary and Conclusions); SBU Report No 175; Stockholm: Swedish Council on Health Technology Assessment.

- Heilbrun, Kirk. 1997. Prediction Versus Management Models Relevant to Risk Assessment: The Importance of Legal Decision-Making Context. Law and Human Behavior 21: 347–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henderson, Rick, and Mike Pochin. 2001. A Right Result? Advocacy, Justice and Empowerment. Bristol: The Policy Press. [Google Scholar]

- HM Courts, and Tribunals Service. 2012. First-Tier Tribunal Health, Education and Social Care Chamber Mental Health jurisdiction: Room Specification Recommendations for Tribunal Hearings; London: TSO.

- HM Courts, and Tribunals Service. 2013. Practice Direction First-Tier Tribunal Health Education and Social Care Chamber Statements and Reports in HMCTS. Mental Health Cases; London: HMCTS. Available online: https://www.judiciary.gov.uk/publications/practice-direction-first-tier-tribunal-health-education-and-social-care-chamber-statements-and-reports-in-mental-health-cases/ (accessed on 5 February 2018).

- HM Government. 2000. Reforming the Mental Health Act: Part I: The New Legal Framework; London: TSO, Cm 5016-I.

- HM Treasury. 2011. Budget; London: TSO.

- HM Treasury. 2017. Autumn Budget 2017 NHS Spending. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/661432/NHS_spending.pdf (accessed on 12 February 2018).

- HL v UK 45508/99.

- Hood, Christopher, Rothstein Henry, and Baldwin Robert. 2001. The Government of Risk Understanding Risk Regulation Regimes. Oxford: OUP. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson v UK (1997) 27 EHRR 296.

- Johnson, Sarah. 2016. The cost of mental illness. The Guardian, May 17. [Google Scholar]

- K v Craig [1998] UKHL 54.

- L v Sweden (App No 1080/84).

- Laing, Judy. 2000. Rights versus Risk? Reform of the Mental Health Act 1983. Medical Law Review 8: 210–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langan, Joan, and Vivien Lindow. 2004. Living with Risk: Mental Health Service-User Involvement in Risk Assessment and Management. York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Law Commission. 2017. Mental Capacity and Deprivation of Liberty (Law Com No 372); London: TSO.

- Leggatt, Andrew. 2001. Tribunals for Users: One System, One Service. London: TSO. [Google Scholar]

- Lintern, Shaun. 2012. Mental health charity funding falls as demand grows. Health Service Journal, May 31. [Google Scholar]

- Lintern, Shaun. 2014. Analysis reveals mental health trust funding cuts. Health Service Journal, August 14. [Google Scholar]

- McCrone, Paul, Dhanasiri S. Sujith, Patel Anita, Knapp Martin, and Lawton-Smith Simon. 2008. Paying the Price: The Cost of Mental Health Care in England to 2016. London: The King’s Fund. [Google Scholar]

- McNicoll, Andy. 2014. Rise in mental health patients sent out-of-area for beds. Community Care, May 6. [Google Scholar]

- McNicoll, Andy. 2015. Mental health trust funding down 8% from 2010 despite coalition’s drive for parity of esteem. Community Care, March 20. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Justice. 2016. Transforming Our Justice System by the Lord Chancellor, the Lord Chief Justice and the Senior President of Tribunals; London: TSO.

- Ministry of Justice. 2017. Tribunals and Gender Recognition Certificate Statistics Quarterly—July to September 2017; London: Ministry of Justice.

- Minkowitz, Tina. 2007. The United Nationals Convention of the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and the Right to Be Free from Nonconsensual Psychiatric Interventions. Syracuse Journal of International Law and Commerce 34: 405–28. [Google Scholar]

- Mulcahy, Linda. 2011. Legal Architecture. Oxford: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Newbigging, Karen, Julie Ridley, Mick Mckeown, Karen Machin, and Konstantina Poursanidou. 2015. When you haven’t got much of a voice’: An evaluation of the quality of Independent Mental Health Advocate (IMHA) services in England. Health and Social Care in the Community 23: 313–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NHS Digital. 2011. Inpatients Formally Detained in Hospitals Under the Mental Health Act 1983 and Patients Subject to Supervised Community Treatment—England, 2010–2011, Annual figures. London: TSO. [Google Scholar]

- NHS Digital. 2017. Out of Area Placements in Mental Health Services Data Quality Statement 2017. London: TSO. [Google Scholar]

- P v Cheshire West and Chester Council; P & Q v Surrey County Council [2014] UKSC 19.

- Peay, Jill. 1989. Tribunals on Trial: A Study of Decision-Making under the Mental Health Act 1983. Gloucestershire: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Perkins, Elizabeth. 2003. Decision-Making in Mental Health Review Tribunals. London: Policy Studies Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Perkins, Elizabeth. 2003. A New Tribunal? Psychiatry Psychology and Law 10: 113–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell V United Kingdom (2000) 30 EHRR CD 362.

- Practice Direction First-Tier Tribunal Health Education and Social Care Chamber Statements and Reports in Mental Health Cases; 2013 October. Available online: https://www.judiciary.gov.uk/publications/practice-direction-first-tier-tribunal-health-education-and-social-care-chamber-statements-and-reports-in-mental-health-cases/ (accessed on 2 February 2018).

- R v Hallstrom, ex p W [1985] 3 All E R 775.

- R v Mental Health Review Tribunal and Secretary of State for Health, ex parte KB and 6 Others [2002] EWHC 639 (Admin).

- R v. Wilson, ex parte Williamson [1996], COD 42.

- Rabone v. Pennine Care NHS Foundation Trust [2012] UKSC 2.

- Re: Officer L [2007] UKHL 36.

- Reynolds v. United Kingdom (2012) 55 EHRR 35.

- Richardson, Genevra. 2008. Coercion and Human Rights: A European Perspective. Journal of Mental Health 17: 245–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridley, Julie, Karen Newbigging, Mick McKeown, June Sadd, Karen Machin, Kaaren Cruse, Stephanie De La Haye, Laura Able, and Konstantina Poursanidou. 2015. Independent Mental Health Advocacy—The Right to Be Heard: Context, Values and Good Practice. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Romans, Sarah, Dawson John, Mullen Richard, and Gibbs Anita. 2004. How Mental Health Clinicians View Community Treatment Orders: A National New Zealand Survey. ANZ Journal of Psychiatry 38: 836–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rose, Nikolas. 1998. Governing Risky Individuals: The Role of Psychiatry in New Regimes of Control. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law 5: 177–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rugkåsa, Jorun, Molodynski Andrew, Yeeles Ksenija, Montes M. Vazquez, and Visser Claire. 2015. Community treatment orders: Clinical and social outcomes, and a subgroup analysis from the OCTET RCT. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 131: 321–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savage v. South Essex Partnership NHS Foundation Trust [2008] UKHL 74.

- Swanson, Jeffrey, Linda K. George, Barbara J. Burns, Randy Borum, Virginia Aldige Hiday, and Wagner H. Ryan. 1997. Interpreting the Effectiveness of Outpatient Commitment: A Conceptual Model. Journal of American Ac Psychiatry and Law 25: 5–16. [Google Scholar]

- Szmukler, George, Rowena Daw, and John Dawson. 2010. A model law fusing incapacity and mental health legislation. Special Issue. Journal of Mental Health Law, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szmukler, George, Rowena Daw, and Felicity Callard. 2014. Mental health law and the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 37: 245–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- The Franks Report. 1959. Report of the Committee on Administrative Tribunals and Enquiries. London: TSO, Cmnd: 218. [Google Scholar]

- The King’s Fund. 2015. Briefing—Mental Health under Pressure. London: The King’s Fund. [Google Scholar]

- The Mental Health Taskforce. 2016. The Five Year Forward View for Mental Health a Report from the Independent Mental Health Taskforce to the NHS in England. London: TSO. [Google Scholar]

- The Tribunal Procedure Rules. 2008. The Tribunal Procedure (First-tier Tribunal) (Health, Education and Social Care Chamber) Rules 2008. (2008 No. 2699 (L. 16) PART 4 CHAPTER 1 Rule 34; London: Ministry of Justice.

- Thomas, Robert. 2017. Oral and paper tribunal appeals, and the online future. London: UKAJI. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, Robert, and Joe Tomlinson. 2016. New ESRC Report Launched: Current Issues in Administrative Justice: Examining Administrative Review, Better Initial Decisions, and Tribunal Reform. London: UKAJI. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. 2014. General Comment No 1: Article 12: Equal Recognition before the Law. Geneva: OHCHR, (CRPD/C/GC/1). [Google Scholar]

- Wexler, David. 1992. Justice, mental health, and therapeutic jurisprudence. Cleveland State Law Review 40: 517–26. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. 2003. Advocacy for Mental Health. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Winick, Brian. 1997. Coercion and mental health treatment. Denver University Law Review 74: 1145–68. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Winterwerp v The Netherlands (1979) ECHR 4.

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Glover-Thomas, N. Decision-Making Behaviour under the Mental Health Act 1983 and Its Impact on Mental Health Tribunals: An English Perspective. Laws 2018, 7, 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws7020012

Glover-Thomas N. Decision-Making Behaviour under the Mental Health Act 1983 and Its Impact on Mental Health Tribunals: An English Perspective. Laws. 2018; 7(2):12. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws7020012

Chicago/Turabian StyleGlover-Thomas, Nicola. 2018. "Decision-Making Behaviour under the Mental Health Act 1983 and Its Impact on Mental Health Tribunals: An English Perspective" Laws 7, no. 2: 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws7020012