1. Introduction

The Royal Palace of Caserta, considered one of the most significant works of Italian Baroque, was commissioned by Carlo III of Bourbon and was designed by the architect Luigi Vanvitelli. The construction of the palace started in 1752 and was completed in 1845. The Palace was built by the Bourbon King in response to the Palace of Versailles in Paris and the Royal Palace in Madrid [

1]. The Royal Palace of Caserta is among the 51 world heritage sites designated by the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) [

2]. The building exemplifies the Italian way of bringing together a magnificent palace with a magnificent park.

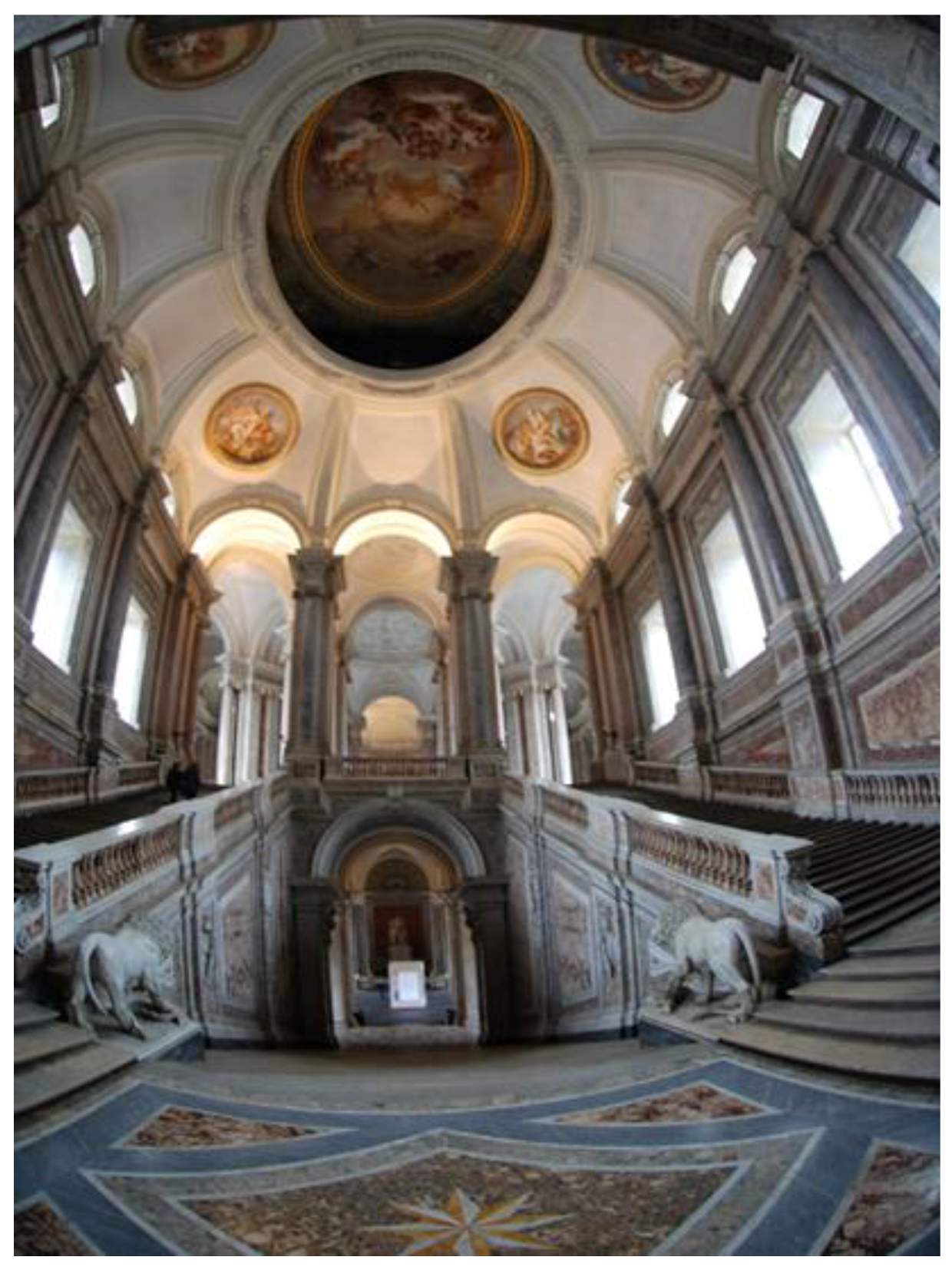

Inside the Royal Palace, the Grand Staircase connects the lower vestibule to the upper vestibule, making possible entry to the Royal apartments. The Grand Staircase is overlooked by a double vault with an elliptical opening (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2). The double vault has two caps, with the lower assuming the role of a large oval cornice. A similar architectural solution was widely used for the realization of domes. Generally, the first dome was blunt, with the upper dome having more points of view for the structural requirements and the weights on the horizontal structures being stabilized. In the 16th century, numerous projects showed the realization of double vaults and domes [

3,

4]. Double-dome structures were used for the dome of St. Paul’s Cathedral by Christopher Wren in London as well as the dome of Les Invalides in Paris, where Mansart developed three caps in 1680. The double-cap model was widely diffused in Italy too, as proved by the dome of St. Maria of Flower in Florence, as well as the dome of St. Peter’s church in Rome.

In the Royal Palace of Caserta, the double elliptical vault presents a great stenographic effect since inside it, on the planking level, musicians used to play for the king and his guests during royal receptions. The musicians played when the royal procession, going up the grand staircase, entered the royal apartments, creating astonishment among the guests who listened to the music without understanding from where it was coming. In fact, the large volume between the two vaults allowed the musicians to hide. This means that anyone going up the stairs had the sensation of being enveloped by the music, which was generally played by stringed instruments inside the double vault.

The aim of this work is to investigate the acoustic characteristics of the double vault of the Royal Palace of Caserta in order to verify the sound effects created by the musicians inside the vault for the listeners on the underlying staircase and in the entrance vestibule to the Royal apartments. For this scope, a sound source was positioned on the planking level of the double vault and microphones were arranged along the steps on the grand staircase as well as in the entrance vestibule to the Royal apartments. Furthermore, the spatial distribution of the acoustic parameters along the staircase and in the entrance vestibule to the Royal apartments are also evaluated using the architectural acoustics software Odeon [

5]. The goal is to describe this ancient Cox’s ‘sonic wonderland’ [

6], which used to be created in this UNESCO world heritage.

2. Description of the Double Elliptical Vault

From the central gate of the Royal Palace of Caserta, there is a large atrium where a long gallery with three naves begins. In the middle of the central nave, the lower vestibule is connected to the upper vestibule with a grand staircase overlooked by a double vault with a central elliptical hole (

Figure 1). Vanvitelli designed the staircase on the axis of the octagonal vault in correspondence to the central vestibule to avoid interrupting the series of sixty-four Doric columns towards the park’s natural backdrop.

The staircase has a ‘fork’ or ‘E’ shape, with a central flight and two side flights overlooked by a double vaulted structure. This type of double vault was widely used in the architecture of the XVI century to expand the space. The staircase is composed of a central flight, almost 8 m wide, which leads to a first landing from where two parallel flights start towards the upper vestibule.

The large stair has 117 steps, with the double flight being 18.50 m wide and 14.50 m high. The volume which houses the staircase is approximately 20 m wide, 24 m long, and 34 m high up to the intrados of the first vault, while the overall height is around 42 m (

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5). Due to its size, the royal staircase is one of the most complex elements of this Royal Palace, with an obstructed plant of more than 600 m

2, which develops over the entire height of the palace and is overcome by a structure with a double vault. From the stairs, it is possible to simultaneously see both vaults thanks to a central large elliptical hole occurring on the lower vault. The elliptical hole has an axis with the dimensions 10.85 m by 14.60 m, while its planking level has an area of about 500 m

2. From the pierced planking level, it is possible to see the second vault, where, at the intrados, there is a painting by Girolamo Starace Franchis titled ‘The Four Seasons and the Royal Palace of Apollo’.

From a structural point of view, the decision to realize a dome with a double vault was probably due to structural needs, since otherwise a single vault would have been 30 m high. Lateral thrusts on the walls have the static function of compressing the resilient ring and limiting the thrust of the lower dome, thus reducing the weight on the wall.

In a letter sent to his brother, dated 14 July 1767, Vanvitelli described all of his satisfaction about the palace, writing that it ‘will be so good when completed, it will surprise everybody, while everything that you do enhances beauty’. For Vanvitelli, the double vault had to have a scenography function thanks to its oval frame. Below the vault, there should have been an iron railing which would have made the view of the staircase more beautiful and the palace, for the people on the top floor, more comfortable; however, this railing was never realized. Only later, at the time of King Ferdinand II, did the elliptical vault start to accommodate the orchestra during royal parties, inspiring surprise among those going up to the apartments of the King accompanied by music that enveloped them fully.

While designing the Grand Staircase, Vanvitelli did not know much about architectural acoustics and the sound behavior in large places. However, several centuries before Vanvitelli, the ‘De Architectura’ by Vitruvio had been reprinted (originally it was written in the first century B.C.). This old text described some fundamentals of theatrical acoustics [

7], together with studies about vaulted places by Athanasius Kircher who worked on how the geometric shape of a room would influence its acoustic behavior [

8,

9], was probably known by Vanvitelli.

One of the most interesting studies by Kircher regarded the elliptical shape of ceilings and the ability of this geometry to reinforce voices. Kircher understood that the ellipse could be used for the construction of a room with an ellipsoidal vault, while it was possible to use the focus of the ellipse to help people communicate with each other at larger distances [

9]. In Section IV of the first book of the ‘Phonurgia Nova’, Kircher described the echo that could be perceived in the interior structure of the Palace of the Powerful Elector of Heidelberg. This room, due to its circular vaulted ceiling, allowed the amplification sound, creating surprising acoustic effects [

10].

Kircher’s works express the typical Baroque vision of the ‘marvellous world’, with machines revealing a strong alliance between science and the magic. For example, among Kircher’s creations, he is often known for his ‘talking statues’, devices that were able to capture whispers from the square [

9]. However, it is important to remember that the rational understanding of the rules of the modern architectural acoustics was started at the end of the 19th century by Sabine, almost 200 years after the death of Vanvitelli. Consequently, it is safe to assume that the acoustic effects of the double vault were more a result of the baroque preferences for unique scenography and large decorated volumes than a rational result of an understanding of the acoustic implications of the double vault.

3. Acoustics Measurements

In order to understand the acoustic characteristics of the double vault and the resulting spatial distribution in the underlying grand staircase, a series of acoustic measurements was carried out. The measurements were taken using an omnidirectional sound source on the planking level of the vault. In room acoustics studies, the standard for performing indoor measurements is the ISO 3382-1 [

11]. This has been defined for performance spaces such as theatres or concert halls. For this case, while the authors agree that the investigated space may not fall under the category of classical performance spaces, it was considered appropriate, given the use of this space, to follow the standard.

Two source positions, close each other, were selected on the vault plane to get to the ‘engineering’ accuracy; the average results are reported below. While more source positions were originally planned, this was not possible as it was not fully safe to stay with all the instruments at the height of the vault, since it has no balaustre, making hard to move at that height in a free manner.

The acoustic parameters early decay time (EDT), reverberation time (T30), clarity (C80), and definition (D50), as defined in the ISO 3382-1, were analyzed. In room acoustics, the reverberation time (T30) is the most common parameter, and it is often described as the persistence of a sound after a source has stopped. The early decay time (EDT) is often shown to correlate better to the reverberation effect in a room, since it focuses on the early reverberation only. The clarity (C80) measures the balance between the useful and detrimental sound for the listening perception, and it is based on an early-to-late arriving sound energy ratio. In particular, the C80 is defined as the ratio, expressed in decibels, of the early energy (that reaching the listener in the first 80 ms) over the late reverberant energy (all the sound energy reaching the listener from 80 ms to infinite). The definition (D50) considers the ratio of the early arriving sound energy over the total sound energy, and in order to reflect the speech intelligibility, it is often calculated using 50 ms as the early time limit.

The sound source used to perform the acoustic measurements consisted of a dodecahedron loudspeaker Peeker Sound JA12 (Peeker Sound Corporation). MLS signals of order 16 with a length of 5 s were generated by a 1 dB Symphonie system. The impulse response was recorded with 1/2’ microphone GRAS 40 connected with a preamplifier 1 dB PRE 12 H. The points of the microphone measure were distributed on the staircase at a constancy pitch in order to obtain the spatial average values of the monaural parameters.

All the acoustic measurements were taken under unoccupied conditions.

Figure 5 shows the section of the grand staircase and double vault, with the 16 receiver positions and the position of the sound source in the double vault. Due to the symmetry of the space and to the double set of stairs, each microphone position on the stairs indicates two points of measure on each stair ramp. The acoustic measurements provided the values of the impulse responses that were processed with the Dirac 4.0 software to calculate the values of the acoustic parameters (EDT, T

30, C

80 and D

50) in the octave bands from 125 Hz to 4 kHz.

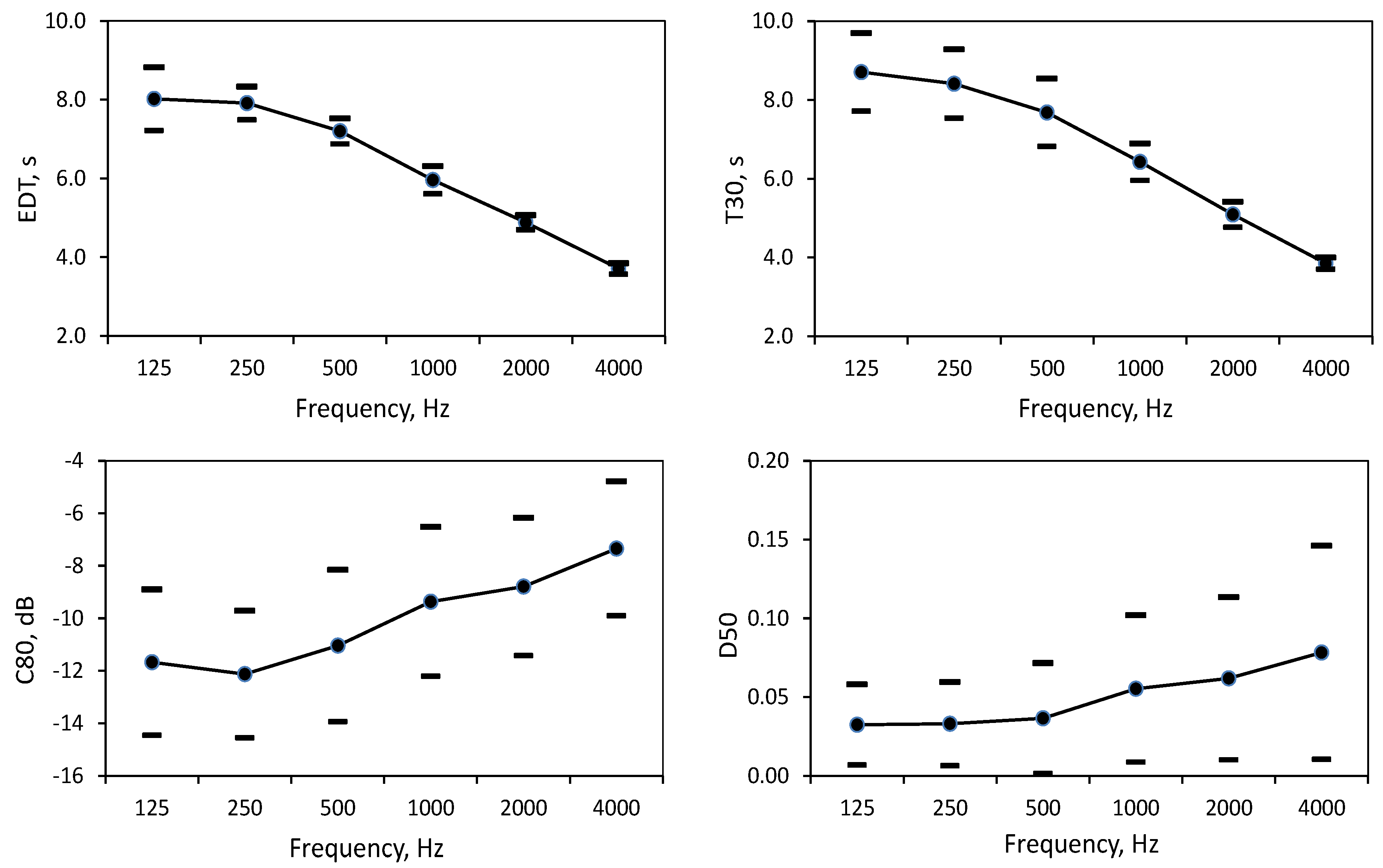

Figure 6 reports the measured values of EDT, T

30, C

80, and D

50, averaged among the fifteen receiver locations, together with the intervals of the standard deviation for each band from 125 Hz to 4.0 kHz. These parameters have been defined in order to better describe the perception of a sound field, even though their prediction depends on many factors, such as the relative position of the sources and receivers. Using recent studies on the typical listening preference, the criteria established in [

12] were used to assess the results of the acoustics of this space. The results suggested that the hall is over-reverberant and not well suited for chamber music or for speech perceptions, given its low speech intelligibility. In particular, the clarity assumes values that are well below those suggested for the sound perception, which confirms the condition of the sound envelope that the listeners experienced without having a clear perception of its direction.

The results at different frequencies allow the important role played by the air absorption of the large volume to be seen. In fact, while the hard marble and rich decorations of the room guarantee long reverberation up to 1000 Hz and extremely low clarity and definition, at the frequencies where the sound absorption may not be neglected anymore such as at 4 kHz, the reverberation time is significantly shorter (below 4 s in all the positions), while the clarity assumes an average value of −8 dB. The relative high standard deviations for clarity and definition are due to the different sound-receiver positions and the fact that the distances from the sound source in the vault for the positions at the end of the stairs are much shorter than at the bottom of the stairs.

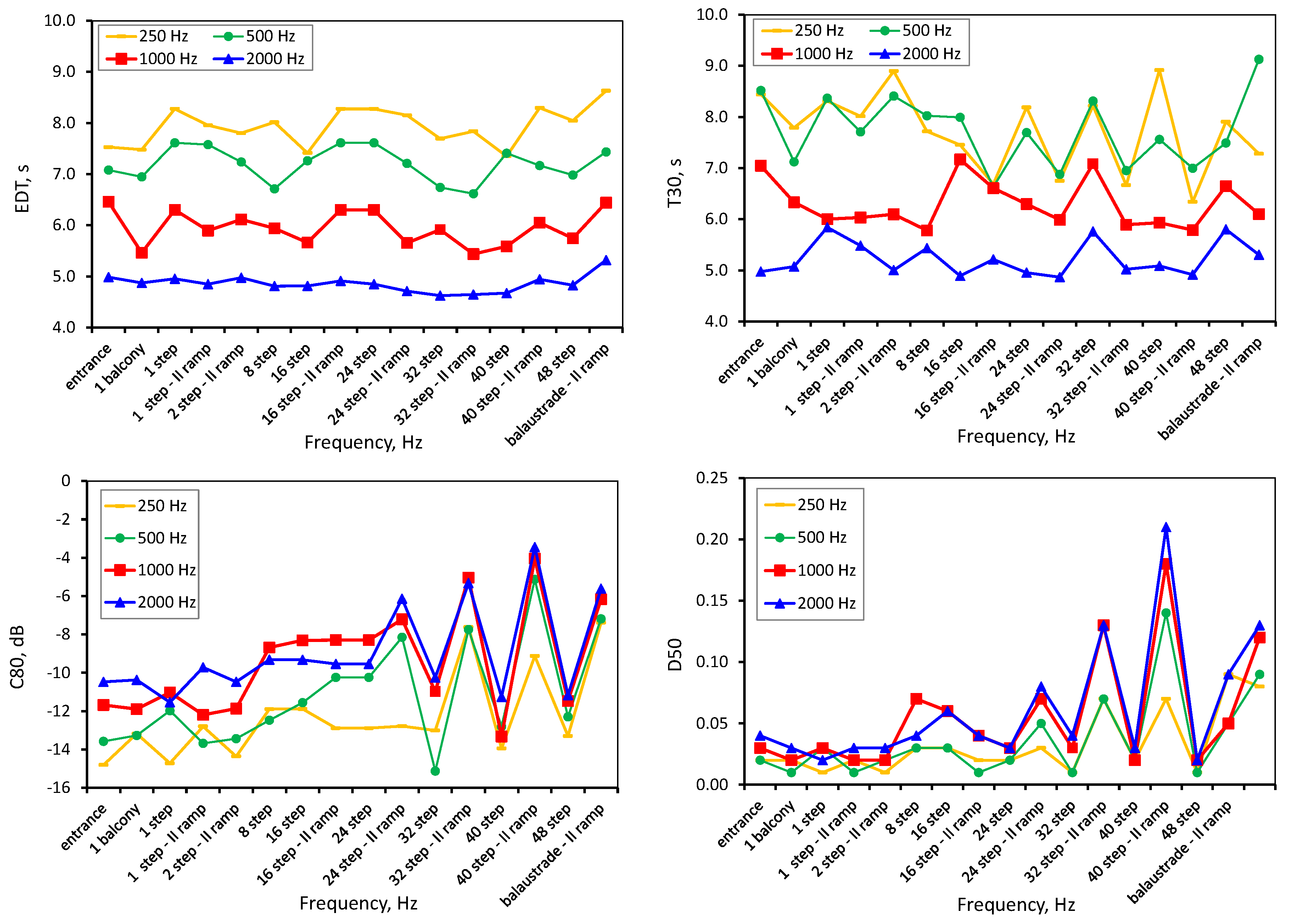

In order to look more in detail at the distribution of the acoustic parameters in the room,

Figure 7 reports the value obtained by the different parameters in the different positions, organized according to the typical procession from the entrance to the balaustrade at the end of the stairs. The results of the measurements suggest that the EDT and the T30 do not vary significantly through the different positions. For example, the EDT is around 5 s at a high frequency (2000 Hz) practically in all the positions, while it assumes a value between 7 and 8 s in the frequency bands of 250 and 500 Hz. This difference is clearly due to the high frequency absorption provided by the large volume of air in this space. The results of the reverberation time reflect in general those of the EDT with the exception of the low frequency values, while some unexpected variations were recorded at the top of the stairs. The general idea of the authors is that the long reverberation, the multiple spaces with the potential coupling of their volumes, and the opened door towards the royal apartments (whose effect was hence more evident only for the last receivers) represent all possible factors for this variation.

To assess the temporal distribution of the sound energy and, in particular, the clarity and the definition, the preferred values reported in [

12] were used. According to this, the clarity is considered adequate in the range from −2 dB to 2 dB, while the definition should assume higher values (above 0.5) only if the speech perception is important, otherwise it may have values below 0.5.

The results show that the clarity (C80) is particularly low at the entrance of the staircase, while when the listener climbs the stairs, the clarity improves significantly, which is also a result of the lower distance between the sound source in the double vault and the stairs. The definition generally remained at particularly low values, confirming that this space is not suitable for speech perception.

4. Computer Simulations

Computer simulations were carried out using the software Odeon to obtain simulated data and investigate further the spatial distribution of the acoustics along the grand staircase. The reason for developing detailed software was also related to the importance of modelling the effects of different source positions within the double vault, a possibility that was impractical during the measurement sessions due to safety reasons.

Oden is software that uses the principles of geometrical acoustics and adopts a hybrid calculation method that combines the image source method (in the first part of the simulation) and the ray-tracing method (in the second part of the simulation) [

5]. The software allows a virtual model realized by a 3D cad to be easily imported. The value of this software is confirmed by its use in similar studies [

13,

14]. In situ measurements made possible the realization of a reticulated version of the geometry of the space (

Figure 8), with the total number of surfaces equal to 3849 and the total inner surface equal to 15,864 m

2.

The software simulation usually starts from the development of a model of the space as it is and for which acoustic measurements are available. Based on previous studies, the simulations were performed by fixing the following parameters; a truncation order equal to 2 (so the image method was used up to reflections of the second order), an impulse response length equal to 10 ms, and a number of rays equal to 50,000.

The acoustic model calibration was done by setting the absorption coefficients and scattering coefficients for all the virtual surfaces. A second step consisted of comparing the measured and simulated parameters in order to allow a suitable calibration of the acoustic model. This made possible the reduction of the difference between the measured and simulated acoustical parameters to minimal values, or at least below the value of a just noticeable difference [

15,

16].

Most of the internal surfaces of the Grand Staircase are flat marbles, which is an acoustically reflective material. The vault is made of a thick structure composed of

cocciopesto, a lime mortar with crushed pottery [

17,

18]. A relatively small fraction of the inner envelope is composed of windows, which have generally high sound absorption behavior. On the ground floor, the staircase communicates to the outside through a wide opening, which has hence a unitary absorption coefficient. Reversely, on the upper floor, the vestibule, which leads to the royal apartments where the floor is marble (reflective surfaces) and the lateral surfaces are plaster walls, is characterized by reflective surfaces. In order to validate the acoustic model, the measured averaged values of the different parameters were compared with the corresponding values calculated with the software. An iterative procedure was used to reduce the difference between the measured and calculated values. This implied slight adjustments to the sound absorption and scattering coefficients. In order to maintain the simplicity of the model together with its practicality, richly decorated surfaces were simplified as flat ones, while their absorption and scattering coefficients were modified accordingly.

5. Discussion

The values of the standard deviations are higher for T

30 and EDT, while they increase with the frequency for the early-to-late energy distribution parameters (C

80 and D

50). This means that the values of these acoustic parameters change significantly from point to point, as evident in

Figure 7, as a result of the change in the source-receiver distance. The measured reverberation time was about 8 s at low frequencies and about 6 s at middle frequencies. The measured T

30 and EDT times are long due to the large volume of the room, which encloses the staircase, and to the presence of the plastered surfaces of the walls and marble floor, which are acoustically reflective.

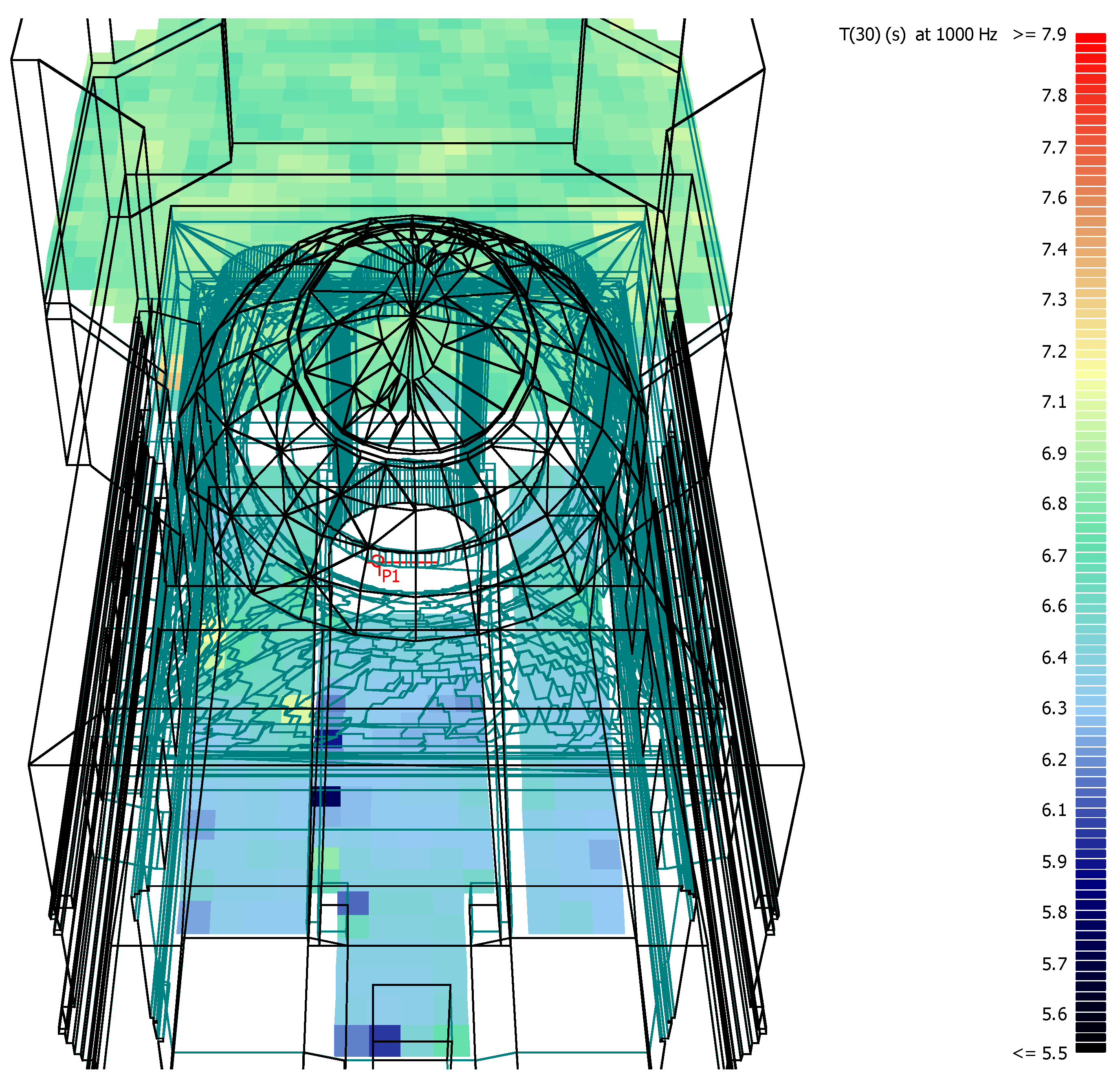

To better understand the spatial distribution of the acoustic parameters, the spatial distribution with a mesh of width 1 meter was obtained.

Figure 8,

Figure 9 and

Figure 10 show the spatial distributions of T

30, C

80, and D

50 in the octave band of 1 kHz, respectively. The acoustic parameter values on the staircase were plotted on an inclined surface.

The maps of the acoustic characteristics provided by the elaboration of the virtual model with the software Odeon give the following indications; the reverberation time is slightly shorter (around 6.0 s) down the staircase, and it is around 7.0 s in the area of the vestibule in front of the entrance of the royal apartments. In this area, the reverberation time remains almost uniform, as if the room was perfectly diffused.

At the frequency of 1 kHz, the parameter D50 along the whole staircase is always below 0.1, confirming that speech intelligibility is particularly poor. In the area of the vestibule on the first floor, the D50 increases slightly, obtaining values up to 0.4 only in front of the door to the royal apartments.

6. Conclusions

The decision of Vanvitelli to build a dome with a double elliptical vault was due to structural requirements and scenography needs, with the cornice running along the vault welcoming music maestros during receptions. In fact, when going up the wide staircase and standing in the vestibule on the first floor, the royal procession could hear the music without seeing where it was coming from.

Based on the measurement results and with the help of the architectural acoustic simulations, it was possible to evaluate the spatial distribution of acoustic parameters that depend on the early-to-late energy distribution. The results indicate that the acoustic parameters vary greatly along the staircase and are relatively more uniform and generally more favorable closer to the entrance of the vestibule towards the royal apartments.

Overall, this study confirms that the practice of placing the musicians in the vault had a great scenic and acoustic effect, which seems to be in line with the baroque decoration of the Palace. Thanks to the large volume of the room with the doubled symmetrical staircase and to the abundance of marble decorated surfaces, which increase the reverberation and guarantee a sufficient diffusion, this room represents a good example of the ‘marvellous world’, which was typical of Baroque culture.