1. Introduction

Towers, skyscrapers, or high-rise buildings, have been surging in the last century as a way of using dense urban lands more efficiently, and representing the progress and modernization of those cities. From its very outset, due to cumbersome load-bearing masonry wall structures, the functionality of tall buildings were extremely limited. It was not until the technology of structural skeleton and curtain walls that this limitation was overcome, opening up the present state of skyscrapers.

Earlier design approaches to some high-rise buildings were sheathed in the false traditional raiment of postmodernity; though, the evolution of modern architecture was more inclined toward modular repetitions and broad abstractions embedded in the International Style. Gradually, the dominant characters of this cityscape became homogenized uniform boxes strongly threatening social diversity and multiculturalism of the contemporary cities.

“Though we have seen major advances in the technologies, efficiencies, and performance of tall buildings over the past couple of decades, arguably the urban expression of the typical skyscraper has not changed much from the predominant glass-and-steel aesthetic championed by modernism in the 1950s ... The rectilinear, air-conditioned, glass-skinned box is still the main template for the majority of tall buildings being developed around the world.” [

1] (p. 91). “Tall buildings ... has made substantial progress in its design in recent years ... when examined more critically, it becomes apparent that much of the latest design work has not progressed so far after all.” [

2] (p. 2). They are like isolated towers, cut off from streets and, therefore, not part of the community, and unable to address certain contemporary issues.

Technology has provided controlled, pleasant, and delightful conditions within the interior of a house for its users. A house has become a Corbusian machine for living in, independent from its natural ecosystem. New mechanical, electrical, and plumping installations, and construction technologies made skyscrapers physically achievable, but the urban globalized expression of the typical skyscrapers have not fit into the cities.

Nevertheless, skyscrapers are now an increasingly common sight not just in American metropolises but also in other large cities around the world, and due to the scale and the impact of these universal edifices, and the volume of consumption of energy and materials, it is of the utmost importance to create a unique sense of place and identity in the design of high-rise buildings. These buildings are “associated directly with modern city, which often has made it the target for criticism of modern urban planning and design” [

3] (p. 3). Ultimately, the intention is to inspire a regionalist approach, rather than an ecological one, where, for example, skyscrapers in Singapore function every bit as well as those in Sydney, but their local responses to cultural identity are very different. Whereas the physical and environmental aspects of the place are easier to define, the culture and heritages of a region are less tangible. Although numerous discussions on the conflict between vernacular architecture versus International Style indirectly address skyscraper dilemmas, dedicated studies that focus on high-rise architecture of regionalism are rarely found.

Critical regionalism thinking seeks to reconcile the global civilization and the local architecture by providing solutions which are fundamentally more based on mid-rise or low-rise buildings. However, most importantly, in the case of high-rise buildings, theoretical promises of critical regionalism do not adequately address certain issues. Even exclusive examples of high-rise buildings with critical regionalism approaches are seldom enumerated.

Critical regionalism has been theorized by Alexander Tzonis and Liane Lefaivre, Kenneth Frampton’s formulation, and many reiterations of the theory, and because of this very multi-facet character inherent to its dialectic structure, it does not stand as a singular theory or practice to be dominant. Indeed, “heterogeneity is intrinsic to regionalist theory, in which there is not one, but as many regionalisms as regions, each specific to its locale and historical circumstances. As such, it is a kind of meta-theory that has only local application and meaning” [

4], (p. 16). Therefore, A holistic worldview approach is demonstrated in confronting with this meta-theory, as all theories in common resist placelessness and lack of identity existed in the International Style, tectonic ornamentation of postmodernism, and homogenizing forces of modern architecture. “In critical regionalism, under Kenneth Frampton, it is defined by a culture’s unique identity, manner of place-making, and architectonic strategies …” [

4] (p. 19). These three notions of critical regionalism—place, identity, and architectonic—are set out to be explored in contemporary high-rise cities.

In this regard a discourse is offered on high-rise architecture looking into the issues of place, cultural identity, and architectonic aesthetic through the lens of critical regionalism. The first three sections troubleshoot the issues related with place, identity, and architectonic. Lastly, it is discussed that architectonic articulation can retrieve the sense of place and identity. When considered endemic to local application and meaning, indispensably the region is specified to clarify the scope of discussion better.

2. Place

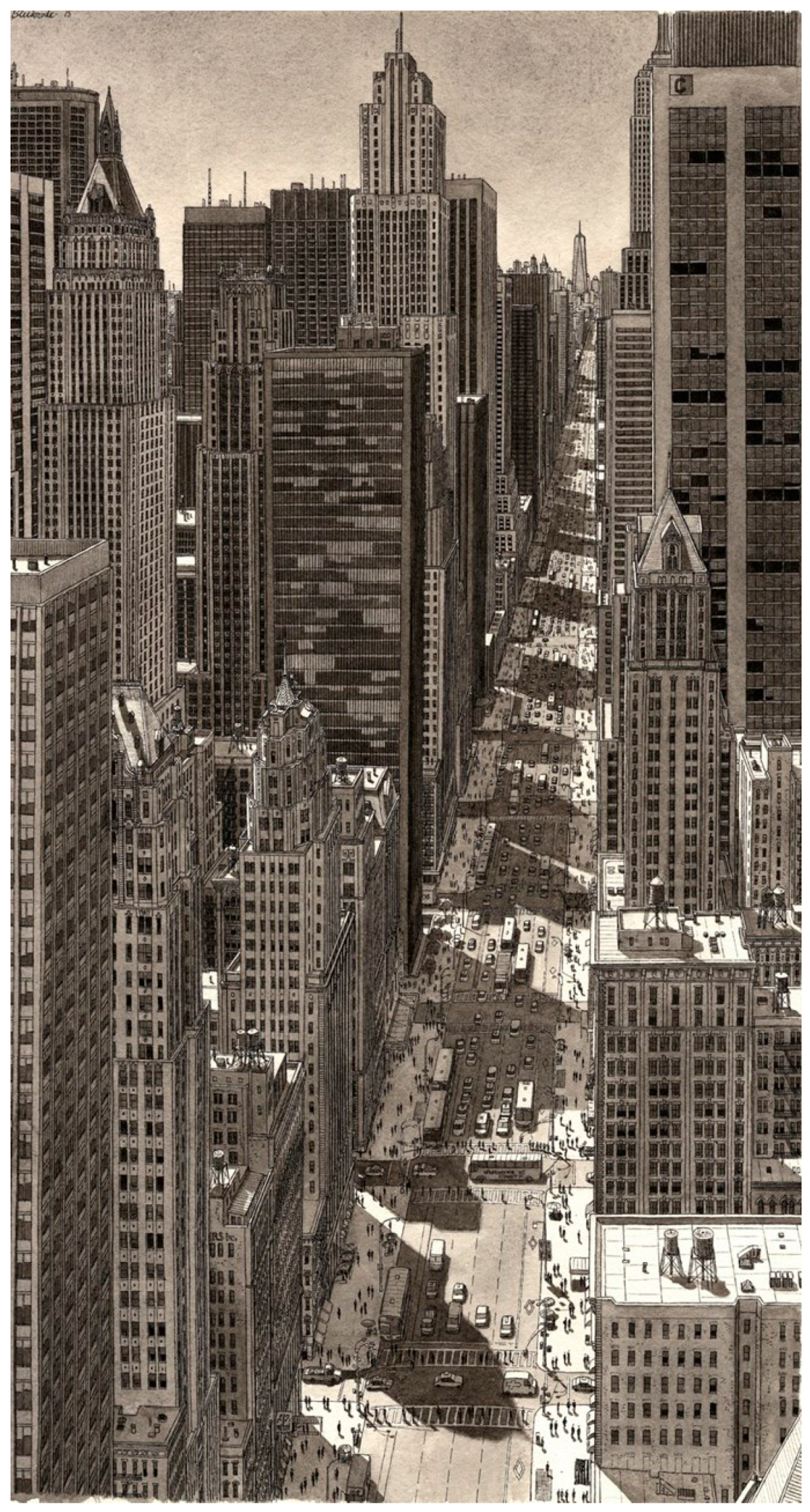

With population growth and the development of urban centers, land has become a rapidly decreasing commodity, resulting in the intense vertical movement of buildings. The result has been stereotypical boxed detached from the reality of place (

Figure 1). Placelessness, the result of rapid constructions and global capitalism, have not only been fostered by International Style, but also the conception of place versus space has changed in its translation from low-rise to high-rise within its context. In fact, the conception of

genius loci is reinterpreted in contemporary high-rise cities.

The first problem which critical regionalism approach puts finger on is the homogenization of International Style which it has totally diminished the sense, meaning, and identity of the place. Instead of providing a high-rise design solution in confronting with mere functionalist and progressive concerns of International Style, theorists have tried to beware architects of high-rise planning paradigms as a threat to social diversity and multiculturalism of the contemporary cities. Probably from this point of view, the best designs are made by architects from countries far from a universal bustle of major cities, in which people rarely would remember that these countries are an autonomous region. Nevertheless, high-rise constructions have been raising from American metropolises to Middle East to Far Asia, and with the growing trend of urbanization, it is only natural to build upwards.

The meaning of place has been changed in its translation into high-rise buildings. Whether willingly or forcibly, people tend to own a piece of sky rather than land. So, the conception of place on the surface of topography is moved toward the space. This resembles astronauts exploring the aerospace for more living space; showing human’s hunger for buying more land even on other planets. It seems what was called upon the place is completely changed through modern era. A single piece of land on the Earth is clearly distinguishable within its neighborhood, but a piece of sky do not bring the same meaning. The concept of many modern buildings is based on using windows extensively to maximize the entry of light into the building by eliminating load-bearing wall. That is, the boundary of a unit is defined by glass curtain walls, resulting in the exterior plot to be as much a part of the home’s interior.

The other facet of place is related with accessibility of

front and

back or

inner and

outer. In Mediterranean or Roman archetype houses, rooms are usually arranged around one or more central courtyard providing light through open doors into the dark rooms. Although these houses are introverted, they are legible by degrees of access. The public outside has been dragged into a multifunctional scenographic courtyard performing as a theater or a music hall for all people; in other words, a scene of emotions and excitements. On the contrary, “current tendency to reduce built form to image or scenography only serves to further an imagistic reception and perception of the built form” [

5] (p. 383). The concept of modern architecture is based on light; thus it is extroverted. While its front façade or outer part of the building is the public places, the back or inner part is the private district where things really happen, and one has to seek for what is behind the scene.

Additionally, there is a relationship between people and the place of the built form which is measured by degrees of participation, both mentally and physically. Despite the main task of high-rise solutions based on saving land, they mostly led to placelessness. Place detachment, the further result of detaching a building from ground into the sky, is often related with direct experience and participation which is often more highlighted when it is transformed vertically, resulting in a spurious relationship with place, blurring the reality of a place and, thereby, diminishing one’s ability to engage and participate fully in the place.

More than any kinds of art, architecture and its context have complex interactive relations with each other. The landscape and natural setting of low-rise buildings are characterized by undulating topography of hills and valleys which formulate the skyline of the city. High-rise buildings, however, have a different relationship with its context in which their construction design could not be consistent with the natural topography of the site, leading to designing a flat landscape or artificial topography around the high-rise building. It technically ignores the topography on the surface of the earth and try to define its own vertical topography in the sky. Incorporating green roofs and vertical landscaping have been more common in the last decades. Tall buildings, fundamentally due to their height, disconnect dwellers from the landscape of the ground. This idea helps to provide a nature-friendly environment, and it brings a new idea of context and landscape, consequently.

Context does not solely stand for topography of the site, but mostly refer to the environment in the case of high-rise buildings. “Manmade synthetic ecological systems can never adequately duplicate the complexity of natural ecological systems.” [

6] (p. 21) (

Figure 2). Contextual response has always been challenging due to the dynamic nature of rapidly growing cities and urban fabric that should be continuously adapted. Even if the regionalism concept is put into practice contextually appropriate, what was suitable a few decades ago is not practical in the present days anymore because its environmental context has undergone changes through the years. For instance, in the past, vernacular architecture in the mountainous area of the Middle East did not tend to be cold and wet, nowadays, the wind and rain are treated as useful resources that contributes to a positive regional architecture. Additionally, “open plans and courtyard concepts which were successful strategies to maximize ventilation and provide thermal comfort in early Tropical architecture, do not function similarly in the congested and space deprived cities of today” [

7] (p. 2).

Unfortunately, architectural researchers seek for technological solutions for skyscrapers more than ever, leading to mechanically-conditioned glass skyscrapers, whose glossy surfaces have adverse effects on climate. For instance, in major Arab cities, each iconic tower is striving for attention lacking any climatic response to sun, heat, and humidity. To be equitable, in some northern countries, this large reflective glassy surface optimizes daylight in relatively cloudy weather. Despite all this, “If nature were allowed to take her course, regional differences, both social and artistic, would be far more pronounced than they are” [

4] (p. 95). Another example, here not in Middle East, but in some successful bioclimatic skyscrapers of Yeang in Southeast Asia, do not only respond to climate matters but create an efficient ecosystems within themselves that mitigate heat and humidity into the human comfort zone to improve the environment of the building’s inhabitants. This approach, integrating climate and cultural strategies, defines a right expression for a tower in hot and humid areas to confront “the relative failure of the Modern Movement to even consider appropriate environmental solutions to the problem of the high-rise in the tropics”[

8] (p. 132). Similarly, in Singapore, “Tay’s interest in tropicality is driven by a clear-sighted avoidance of symbolic quotation and the need to adopt technological form to tropical climates” [

8] (p. 132). “Regional planning, then, takes as its starting point the unique mix of resources and the common background provided by the region. Its aim is to reshape the given state of nature into a humanized landscape that more completely fits the physiological, aesthetic, emotional, social, and economic needs of the human inhabitants of a given area”[

4] (p. 352).

The sense of place in critical regionalism ideas goes a step further into a broader image of the city in which buildings and infrastructures should not be seen as statistic assemblies, but as interactive, dynamic, and integrated systems that constantly improve themselves in response to contextual changing parameters in their urban fabrics.

It seems completely nonsensical that cities are making a push for ever-denser, ever-taller urban forms, but allowing only the ground plane to be the sole physical means of connection between towers.

Skybridges and

Skyplanes ... have the potential to enrich both tall buildings and cities, allow the sharing of resources between towers. There has hardly been a science-fiction city of the future created in the past 100 years that has not embraced the idea of the multi-level city [

1] (p. 99).

An early manifesto of Futurist Architecture, which is illustrated in

Figure 3, for instance, describes a highly industrialized and mechanized city of the future in which the city does not consists of individual buildings but a multi-level, interconnected, and integrated urban design envelop the life of the city. In this sense, modern progress has to be joined in groups of buildings that support, rather than recoil against, each other in their context.

“Supertall buildings of enormous scale and mixed uses may be better understood as self-contained cities in a global context instead of buildings in an urban context” [

9] (p. 820). Urban centers throughout the world are influencing the design of the supertall buildings as “a city within a city” and “a city in the sky” [

3]. “Tall buildings have the versatility to accommodate uses other than the standard office, residential and hotel functions that currently predominate” [

1] (p. 96). Surprisingly, in the city of Whittier, located in Alaska, instead of providing a local solution to build sustainably in an extreme northern climate, all activities of the town take place in a single apartment. This unique concentration of activities and housing makes it the most important building of a small town, giving it the name of

town under one roof.

We need to replicate the existing facilities and essential elements of life at the ground plane up in the sky; this means that the ground plane needs to be treated as an essential uninterrupted and a duplicable layer at the same time. The duplicated layers, on the other hand, should be, in a supportive way, rather than blocking out light and view and sucking out life away from the street. Variable conditions in the climate and environment also will be needed for a holistic approach to consider the urban setup as a whole and beyond an individual building.

To sum up, transforming the conception of place that was brought about by high-rise buildings catalyzed the disruption and loss of place in modern architecture. The interpretation of place in critical regionalism ideas is more based on classic deception of the place and, thus, fail to cover the current hybrid multi-layered definition of place versus space. Today’s high-rise architecture can be best understood only through pluralism. It must be asserted that due to the massive scale of high-rise buildings, they often contribute to serious place-making problems which require more advanced building technology and an integrative design in which summon architects, engineers, and constructors.

3. Identity

In response to the nationalism prevalent in the world war eras, the modernists tried to undercut the notion of regionalism in favor of a global peace. The dissemination of these universal assumption and also the great need for post-World War II reconstruction fertilized the seed of International Style crawling out of any ornaments and identity of place [

10]. As such, the blank façades of the buildings lost any notion of cultural memory and regional identity (

Figure 4). “The International Style was intrinsically linked to modern art and was therefore inadequate in relation to the regional cultural heritage” [

4] (p. 188). A vast variety of iconic tall buildings have been raised, each exhibiting diverse forms and types without addressing the idea of place, and being specifically related to that city. They resemble each other in such a way that could be imagined in almost any global city around the world. Meanwhile, critical regionalism ideas tried to balance between International Style anonymity and local identity, without considering that the parameter of height over high-rise buildings could potentially become a powerful tool for expressing the national identity.

As in the middle-ages or the early days of Islam, high steeples or minarets exhibiting the pride and prestige of their dominants, in modern era, likewise, skyscrapers have become a means of boasting power among countries where, due to a competitive situation, some projects evidence that there are rivalries over whose skyscraper is taller. “An aggressive race to earn the world’s tallest building title continues” [

12] (p. 43). It actually equates height with power and pride. “The current urban core densification is reviving the drive for monumental high-rise construction. Tall buildings are paradigmatic of the representation of power in the city.” [

13] (p. 28).

In religious societies, especially, nationalist sentiments are aroused by impressive objects such as skyscrapers. Obviously, the symbolic statement of these edifices can induce a better sense of nationalism than low-rise or mid-rise buildings (

Figure 5). Major Arab cities are making investments in building skyscrapers, not as a result of scarcity of deserted land, but for prestige. This problem is due to clients who ask architects for

icons. Nowadays, skyscrapers have become the decoration and prestige of these cities once ornamented by domes and minarets, and oriented the skyline of Islamic cities, trying to define the city’s identity.

The most desirable characteristic of an authentic architecture of regionalism rooted in expressing values, heritages, and the culture of that region, Allowing one to present his own interpretation while communicating with the principles of belief, behavior, and aesthetic that define the lifestyle. The designs also should employ traditional and historical features not as superficial attachments, but integrally in the concept and forms of buildings. “Here fake regionalism—with a few gingerbread

historical attachments over an ill-conceived modern structural box—was a constant danger … A sounder approach lay in the sort of modern regionalism mentioned … in which an attempt was made to unearth fundamental lessons in local tradition and to blend them with an already evolved modern language” [

14] (p. 357). There are numerous false examples of the post-modern approach in which the tall building is ornamented in motifs that borrow some aspects of ancient architecture, or worse, the local forms are stretched vertically to reach the height of a tall building, and some parts do not simply fit into, like an awkward cupola or sloping roofs that are no longer convincing in modern designs of tall buildings. Current structures use form and shape to reference pagodas, minarets, domes, and many other forms. It shows that this current tendency has not fully moved beyond post-modernism. There is still attachment to symbolism, even though the symbols have changed. “There is much more to our current place in architectural history than symbol and iconography. Rather than symbol, the specifics and the tools and the methods we use to build should be the basis for a new kind of high-rise building that would inherently

add value but also transform cities” [

2] (p.2).

In less developing countries even some firms consciously imitate post-modernist architecture by incorporating Western symbols or features. “They were designed by contemporary artists according to specific iconographic political programs written by poets-historians-diplomats to give to the events a reconstructed,

antiquated character alluding to Roman or Greek mythology or history as universal models to justify the present and prescribe the future” [

15] (p. 20). There is an ill-conceived belief that the glorious period of the ancient Greek should be taken as a valuable trophy to show the grandeur of the buildings.

Most regions with the tallest buildings have shifted in recent decades from the United States to Asian and Middle Eastern countries. Among them some, as a boastful claim of world centrality, are built for expressing economic power, with no economic justification. Some examples are criticized for being lavish and extravagant, exhibiting the dreams of an emerging wealthy society. Their volume is monumental, and their exterior is prodigal.

In order to democratize the nationalist face of the high-rise buildings, they should be no longer an expensive extravagance but “a crucial development vehicle engaging the middle classes. In this process of democratization the high-rise has exceeded its natural milieu as workspace and pervaded all aspects of urban life … Because of its engagement with domestic protocols and specific climatic conditions, the vertical envelope is now producing culturally-specific, vernacular varieties” [

13] (p. 28).

In contrast to the idea that skyscrapers are merely functional outputs of globalization, it is sometimes argued that skyscrapers, even though they are not lucrative, grant identity to the cities through the skyline, an identifiable array of icons that provide orientation for walkers and drivers. Skyscrapers have obtained their own history and memoirs visualized in many movies, pictures, and postcards. This symbolic quality of skyscrapers are flourished in cultural or economical capitals to present the symbol of their nation. Signature skyscrapers of national identity are allocated the highest priority to be designed very unique and tailored to the national identity. Some countries have found mega-objects such as skyscraper with particular design to potentially become an iconic national significance so that they retain the heart and soul of the city.

High-rise architecture could serve to overthrow national culture and vernacular characters, or if designed properly, it can role as an identifier for cities. Some remarkable high-rise projects have clearly attempted to embrace traditional forms. The architects look for motifs, symbols, or archetypes from artifact or natural sources to formulate the design based on them. Sometimes the reference is a mythical place, and the myths have separated from its factual history. Although these traditions might be an important part of folks’ culture, most ordinary viewers will not even be notified or are not interested in sophisticated philosophical metaphors that may only be concerned by intellectuals.

It is very questionable whether these references actually signify any cultural identity or improve the sense of place, and do we really need to account for these references in the modern era? Why should we limit architecture to the culture that surrounds it? Why can we not bring and learn from other cultures and use materials not locally available? Indeed, religious belongings of sacred places, such as steeples, minarets, or pagodas, have nothing to do with profit-seeking secular modern skyscrapers that cater to human’s physiological needs other than spiritual religious ones. These symbolisms have the capacity to transform into various forms, but still there is no point to restrict ourselves with certain patterns. These symbolic commercial forms are indeed a pure reflection of the finance-oriented and image-obsessed of today’s global culture.

The aforementioned high-rise samples are very unique examples of traditional vertical architecture in a particular region and thus possible to emulate in contemporary high-rise architecture. Unlike ancient or historical cities, which at maximum contained only a few distinctive landmarks, the modern city is a collage of high-rise buildings that compete with each other. Another critical issue arises when it is assumed that every high-rise building in a region should follow a unique vertical notion, then the city’s appearance will suffer from sameness and boredom, surprisingly, this time not through homogenization of International Style, but with the monotony of regionalism architecture.

High-rise regional works in some regions may be more successful than other regions in terms of providing visual references to a particular archetype. In some regions, however, vertically-built examples rarely exist that could inspire architects. In fact, there are not quite so many vertical elements in a specific region to borrow from. Such regional references have been mainly characterized by low-rise architecture, and they contain limited applicability to be translated into high-rise architecture.

It is often asserted that high-rise structures are not comforted with any local low-rise design traditions in non-Western societies. Even researchers sometimes surrender to the fact that non-western regions lack any skyscraper history, and the precedents of skyscrapers are exclusive to Western societies which should be imported from. Skyscrapers impose American cultural hegemony all over the world. A monoculture universal template of North American design of so called

Manhattanization or

Chicagoization, like the drawing of

Figure 6, is characterized by windows running in horizontal rows forming a cube transplanted into non-Western countries with little or no modifications. “As a practical matter, the high-rise building had to function within the fine-grained checkerboard pattern of the American city” [

3] (p. 5). This high-rise precedent denies local identity through universal applications of technology, business formulas, and design standards. Of course, it is difficult to talk about indigenousness in high-rise buildings with only 130 years of history, which has now spread from its North American roots to encompass almost the entire world.

Surprising though it may seem, many vernacular styles of high-rise buildings are imported products from the West. “Today, in the era of pluralism, cities in Asia and the Middle East try to establish global identities with large-scale tall buildings having unique forms designed by starchitects” [

9] (p. 820).

Experienced foreign architects of repute are often invited by developers and owners in less developed countries to provide the design of skyscrapers of special significance, such as national landmarks. This matter is of particular importance in cities that are witnessing rapid growth. The lack of experience of local professionals compels the owners and developers to take the attitude that name-brand architectural firms from outside their own countries are more qualified to do the job. They do not want to take a risk with their investment on costly projects, such as skyscrapers. In many cases, these firms may not be attuned to the local culture, whereas local residents may cherish their own cultures and desire to ensure its continuity via the built environment [

12] (p. 45).

Developing, and even industrialized, societies are dealing with an apparently contradictory crisis of identity which should be reconciled. These societies, on one hand, try to revive their regional identities and heritages; on the other hand, they put so much effort to be a part of world civilization with international standards and a universal subscriber identity. These cities consist of juxtaposition of buildings with reactionary attitudes that empower their past, and innovative tall buildings looking into the future (

Figure 7).

All of this goes to show that due to economic prosperity or scientific advancement, the policy of some countries is deliberately based on creating iconic skyscrapers to support place-making. As the high-rise buildings play a vital role on expressing the values of a nation, they are an important contributing factor of urban landscape homogeneity. Eventually, political leaders and city officials with consultation of architects and urban designers will possibly need guidelines that specifically indicate the priority and hierarchy of applying cultural references. These limitations warrant the overdose of cultural infusion. The crux of the problem lay in the lack of any specific mandated guidelines. If it is assumed that any buildings intimate the same pattern then the city will begin to lose its identity and turn into a placeless place. As a vertical city, high-rise architectural programing should be examined against cultural needs, values, and preferences. It must be understood what makes something truly memorable: it is important to put aside sentimentality and grab new contemporarily-identifying ideas.

4. Architectonic

Gothic stone cathedrals, Persian brick minarets, Chinese wooden pagodas, limestone pyramids of Egypt, and Yemen’s mudbrick towers are manifest examples of traditional vertical architecture which have been evolving gradually over centuries. Their functions in response to particular needs, less or more, resemble to contemporary high-rise buildings’, but with differences established in their regional flavor. The aesthetic of these ancient structures comes along with authenticity often driven by architectonic strategies in necessity of using material and local practitioners followed certain patterns of design and construction methods. Critical regionalism ideas value upon “local economies, utilizing local labor and acknowledging local material and spatial associations”, which make the work of each region distinctive [

4] (p. 110).

Authenticity, the central concept of regionalism in modern architecture, “serves as a caution and a guide for those who wish to successfully build regionalist works … It is not a property inherent to things or places but a measure of our connection to them … [It is suggested] that the authentic object or environment must be

of undisputed origin, its form should be connected to its process of creation; it must be genuine, things are what they appear to be or what one expects them to be” [

4] (p. 26).

For some time, however, architectonic and authenticity, two integral factors, went separate ways. In fact, a fitful fad of postmodernity and flashbacks to traditionalism were to encompass modern façades. “It fostered a superficial attachment to the symbolism, rather than the emancipatory possibilities, of technology, replacing the historical revivalist architecture that preceded it with an equally empty anti-humanist aesthetic based on those symbols.” [

4] (p. 288)

“It remained for Adler and Sullivan … to express adequately the structural frame of the building in its external lines. This was achieved by giving the vertical members, which carry the main loads, dominance over the horizontal members”, then the loads of one floor will be carried upon a skeleton framework, with no need of masonry structures of wall-bearing types [

16] (p. 94). In most cases, the floor-plate form assembled by columns is a consequence of economic and functional formulae, resulting in an indistinguishable architecture.

Most high-rise buildings follow a standard design and construction principles that could be found almost anywhere in the world, a

synonymous association rather than

indigenous. This demonstration of “function versus form set a precedent that was to shape all subsequent skyscraper design”, without carrying specific meaning [

16] (p. 94). “Modern Functionalism rejected tradition and ornament and therefore eliminated the primary traditional insignia of local origin. This set the stage for an international style that was radically new and could in principle receive equally relevant contributions from anywhere in the world” [

13] (p. 384). For this very critical issue of modern homogenization, critical regionalism assertions do not provide a sensitive high-rise design solution. This, by itself, will lead to uniform homogenized tall boxes with glassy façade which initially stand in International Style, and architects sometimes only “attempts to regionalize the International Style.” [

4] (p. 214).

Moreover, many high-rise construction developments intrinsically cannot respect the local topography:

peaks and

valleys of the building site are often

flattened to accommodate easier and faster construction methods [

15]. These constructions are clearly antithetical to the natural topography, and contradict the idea that had gained in critical regionalism approach. It is sometimes argued that “

technology and

place should be understood as the suppressed core concepts that are contained within regionalist architectural production” [

17] (p. 433). Adaption of a house in its context is something that has been addressed in numerous regional works, insofar as “sometimes regionalism is minimally interpreted as a response to the local climatic conditions or specific topography” [

4] (p. 21). However, “High-rise constructions tend to become disjunctive in this regard” as admitted Kenneth Frampton in his remarkable essay on critical regionalism [

5] (p. 382).

This is despite the fact that every latitude and facet of a high-rise building experiences considerable different climate conditions. The industry is now realizing that climate varies significantly with height and, thus, some of the great heights being achieved with tall buildings today effectively means that we are designing single tall buildings that cut across multiple climate zones. So, climatically, the group levels of stories, or each side of the building, need to be treated with different types of openings, materials, etc.

A tall building should, thus, be considered as a number of stacked communities according to the opportunities of each specific

horizon, both climatically and physically in its relation to the city, rather than extruded as a single monolithic form from the ground floor. This could manifest in the manipulation of building mass as well as program, and there should also be variance in skin and texture throughout the building, depending on the responsibilities of each different horizon within the form [

1] (p. 96).

It is like the amount of structural material required within the lower levels which is much larger than the material required within higher levels. However, the problems posed in high-rise design are mostly engaged with balancing between economics, engineering, and construction, and, unfortunately, this variation of climatic design could be merely taken into account. This has obliged engineers to resort to technological solutions for high-rise buildings, leading to mechanically conditioned glass skyscrapers, whose glossy surfaces do not reflect any climatic justifications. Behind their faceless façade, high-tech facilities are concealed, extensively used for high-rise buildings worldwide. Frampton aptly explained this situation:

Modern building is now so universally conditioned by optimized technology that the possibility of creating significant urban form has become extremely limited. The restrictions jointly imposed by automotive distribution and the volatile play of land speculation serve to limit the scope of urban design to such a degree that any intervention tends to be reduced either to the manipulation of elements predetermined by the imperatives of production, or to a kind of superficial masking which modern development requires for the facilitation of marketing and the maintenance of social control [

18] (p. 17).

Local practitioners serve as a key role of the architectonic pertinent to the reflective practice of a critically regional architecture in which local labors and craftsmen engage to create the product. Critical regionalism consciously efforts to unify local craft with modern design, a tradition that persists to the present day. This may be appreciated for small-scale buildings, but in large-scale planning so far, it has been demanded for a collaboration between architects and engineers worldwide. Given a tangible statistic, “the vernacular styles of Asian supertalls are the product of architects from the United States or other Western countries … Among the 92 supertall buildings completed or topped-out in Asia or the Middle East, 48 buildings were designed by Western architects, predominantly U.S. architects, and 44 by local architects” [

9] (p. 818).

Another concern, however, is substituting human involvement with machines. “There is interest in all digital and robotic fabrication in architecture, but the construction process of tall buildings maintains aesthetic aspects that are inherently un-robotic.” This issue is resulted in “growing inequity, unemployment, and environmental degradation” [

2] (p. 6).

It should be borne in mind that critical regionalism works are not only the matter of construction but also a well-organized coordination between architects and engineers. Altogether, new materials, inventions, and systems of construction, further consequent of industrialization, have come to shape those insensitive rigid boxes into more flexible forms.

5. Discussion

It is discussed that various concerns of high-rise buildings touch upon the disconnection of quality of place and cultural identity with the effects and possibilities of modernity and technology. After explaining that high-rise standardized design and construction principles lead to faceless anonymous buildings through homogenization, it remains for architectural researchers to translate the strategies of regional responses that were applied in the past to be adapted to today’s high-rise buildings; in other words, make it critically regionalist. Adaptability, the very core of critical regionalism, in transferring the conception of place and identity to the high-rise definition deals with various parameters and variations. For this, a higher level of form complexity and tectonic articulation will give rise to alternate solutions for placelessness and lack of identity which is rooted in early modern designs.

The earlier structural performance of so called passive designs had to meet the needs of structural regulations of high-rise buildings. Engineers’ contributions to architecture served as verification instruments, which means an architect’s design is controlled by civil engineers who verify the designed buildings to be complied with the required criteria.

Unlike retroactive engineering oriented form-finding approaches, many of today’s sculpted complex-shaped tall buildings fundamentally follow a form-making approach. “For extremely tall buildings, structural systems cannot be configured independently without considering building forms” [

9] (p. 830). Certain forms could still be quite difficult to achieve; complex forms, such as twisted, tapered, tilted, free forms, and their combinations, are generally more effective than prismatic regular forms.

Brought about by computational technology, structural behavior of these complex-shaped forms could be simulated, analyzed and optimized. Herein both the possibilities and threats of technology should not be disregarded; overdosing the false complexity will produce a faceless architecture, further fueling the problems, as Curtis in his book

Modern Architecture since 1900 quotes from Van Eyck: “I dislike a sentimental antiquarian towards the past as much as I dislike a sentimental technocratic one toward the future. Both are founded on a … clockwork notion of time” [

14] (p. 367). Sometimes, the designers do not mine the cultural, environmental, and economic potentials, but they simply manipulate form for form-making.

In this regard, a groundwork should be established “on the fertile overlap of critical regionalism and digital process” as it is named the “digital regionalism” realm, to find potentially sophisticated and adaptive structural solutions for hyper-complex geometries in which these new complex surface geometries might be interpreted regionally, and how they might be translated in terms of conveying meanings [

19] (p. 8).

Now engineers are able to analyze many permutations and have the ability to analyze forces that are affected by local conditions, not simply the ones acting in a Newtonian straight line. This gives structure the potential for a specific and local response resulting in a much finer, and perhaps more irregular, grain [

2] (p. 5).

Although engineering solutions, with the advance of structural analysis techniques using computers, have provided ease of simulating in complex building forms, providing this groundwork is crucial for architects to be able to closely collaborate with engineering and craftsmanship to create articulation between spatial and structural qualities of architecture. An integrated design process for high-rise buildings is needed to unify them into a coherent design based on the contextual strategies and principles of regional design. “Regionalism in the context of the digital era is increasingly concerned with the integration and regeneration of physical information and virtual data through new technologies.” [

20] (p. 93). Integrative regional design is more critical for high-rise buildings than any other building types, due to their enormous heights and scales, which require the most advanced building technologies and have a greater impact on urban and even global contexts.

It seems totally sensible to develop the pre-rationalized rigid structures of high-rise buildings through a multi-dimension spatial-structural relationship which is based on adapting the critical regionalism approach with integrated customized tectonic articulation, digital construction, and material computation.

The discourse of critical regionalism in the modern era arise broad social, cultural, and ethical criticism opened for further discussion and research. It is hoped that this pathology sheds more light on the required groundwork to implicate structural performance design method and techniques in order to foster place-making and identity-giving in high-rise constructions.

6. Conclusions

As the global homogeneous epidemic of International Style skyscrapers transmitted over the world, a backlash against the lack of identity and placeless of the International Style emerged in the form of critical regionalism; a response to tectonically-vacuous, superficial postmodern architecture, and the homogenizing forces of modern technology. It is established that principles of critical regionalism of low-rise buildings that were creating successful regional architecture, cannot work in the same way at present in the wake of skyscrapers. It is explained that high-rise construction does not bring the necessary response to place and topography, a sense of reality to the cultural identity of architectural form, and the possibility of engaging local labor and skill in architectural production.

These issues of high-rise buildings have been addressed by the aesthetic of the built form fed off architectonic articulation. The aesthetic of buildings is neither the only, nor the ultimate, objective of the architecture of regionalism. However, in the case of high-rise buildings, providing novel forms becomes more significant because they are visually more profound in relation with many places far and wide in the city, at differing horizons within its form. This visual dialogue with these distinct places can help inform a variance in form to further connect the building to its locale. Due to structural and installation requirements, the form of these edifices are still limited in embracing unconventional forms. Complex-shaped forms for high-rise buildings will definitely require more complicated technological systems of design and construction.

It is important to moderately work with the knowledge that has already been acquired and start adapting the critical regionalism approach with the best technological achievements possible, rather than waiting for the perfect solution and do nothing until then. Structural, and other related performance issues should be considered holistically to produce a higher regional quality. Tectonic articulation between architecture, engineering, and craftsmanship can fill the gap between critical regionalism approaches and the technological responses, which permits regional differentiation, adaptions, and modifications. Whatever its pattern, it should help to stamp the architecture of a region as truly regional.