ODA exists through others, and two opposing conceptual points are conversely drawn out by the others: the “here” and the “there”, which also imply the existence of the in-between. In particular, the external data of retrieval ODA comes from one place (the native context) but belongs to a different place (the ODA work); this “other place” cannot be overlooked as far as reflections on the processes of an ODA and the shuttling between these two places are concerned. This is also why the means by which external data mixes in-between these two places to become embedded within art and to continually renew itself is an issue that is worthy of study. The following section discusses the notion of the in-between, between the ODA and others.

4.1. The In-Between That Is Constantly in Flux

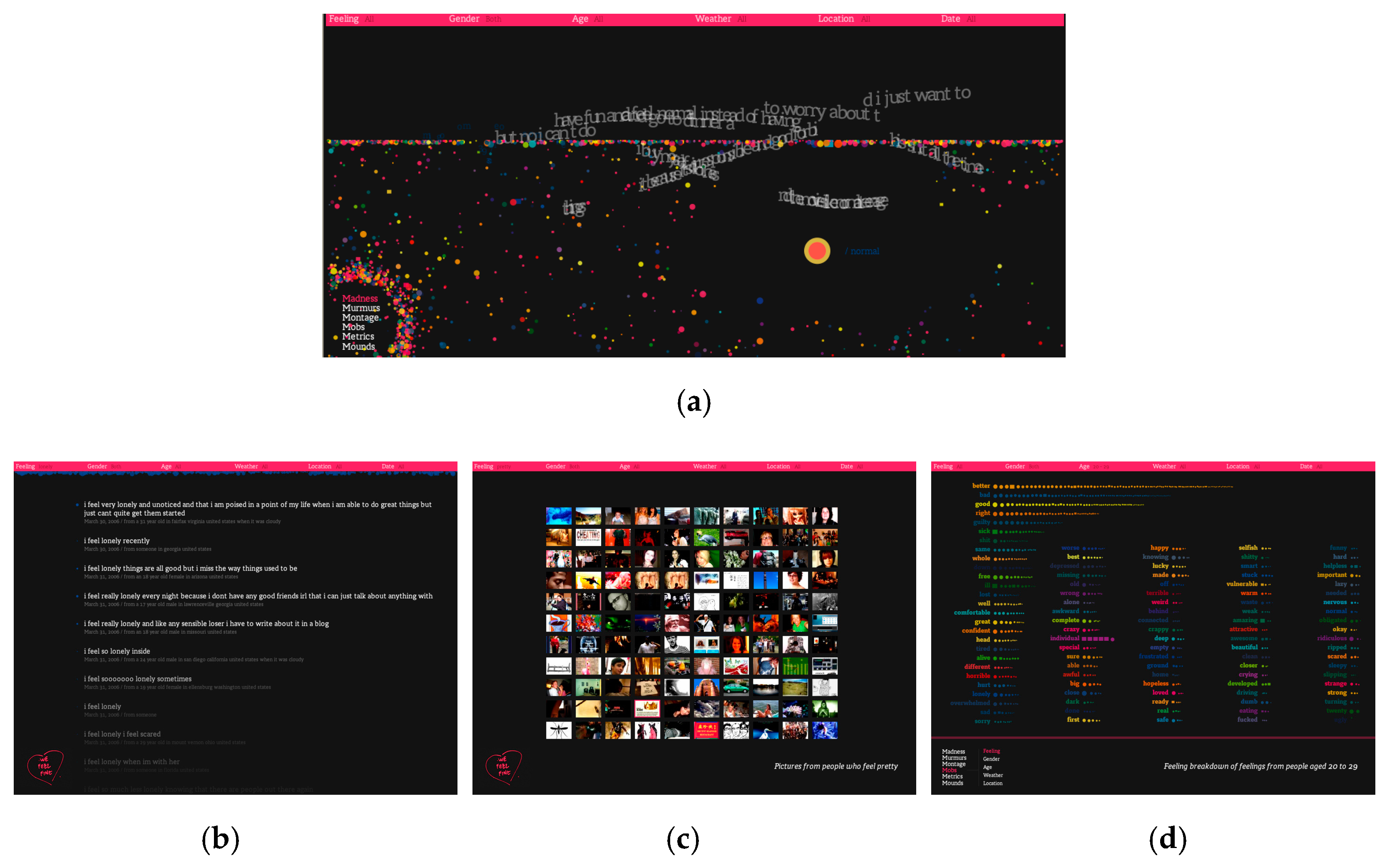

All of the ODA artists do not directly complete the content of the work and do not directly reveal the work, but rather queries the world of the internet through the frame of the work. The responses to these queries are the data that is searched and retrieved, and these answers form the content of ODA works. Regardless of whether the data was obtained through programs or contributed by participants, these data can be seen as a type of product of ODAs. However, the implementation of an ODA work is not just about aggregating data, but rather is more about constructing an accumulation of relationships. A multitude of unrelated people have traces of their existence left behind in an ODA, regardless of whether these were intentionally left behind in participatory ODA works or taken without any prior announcement in retrieval ODA. These traces are aggregated and revealed within an ODA work, such as every scene of the canvas in

Swarmsketch (

Edmunds 2005), the smearing and splattering of the virtual walls in

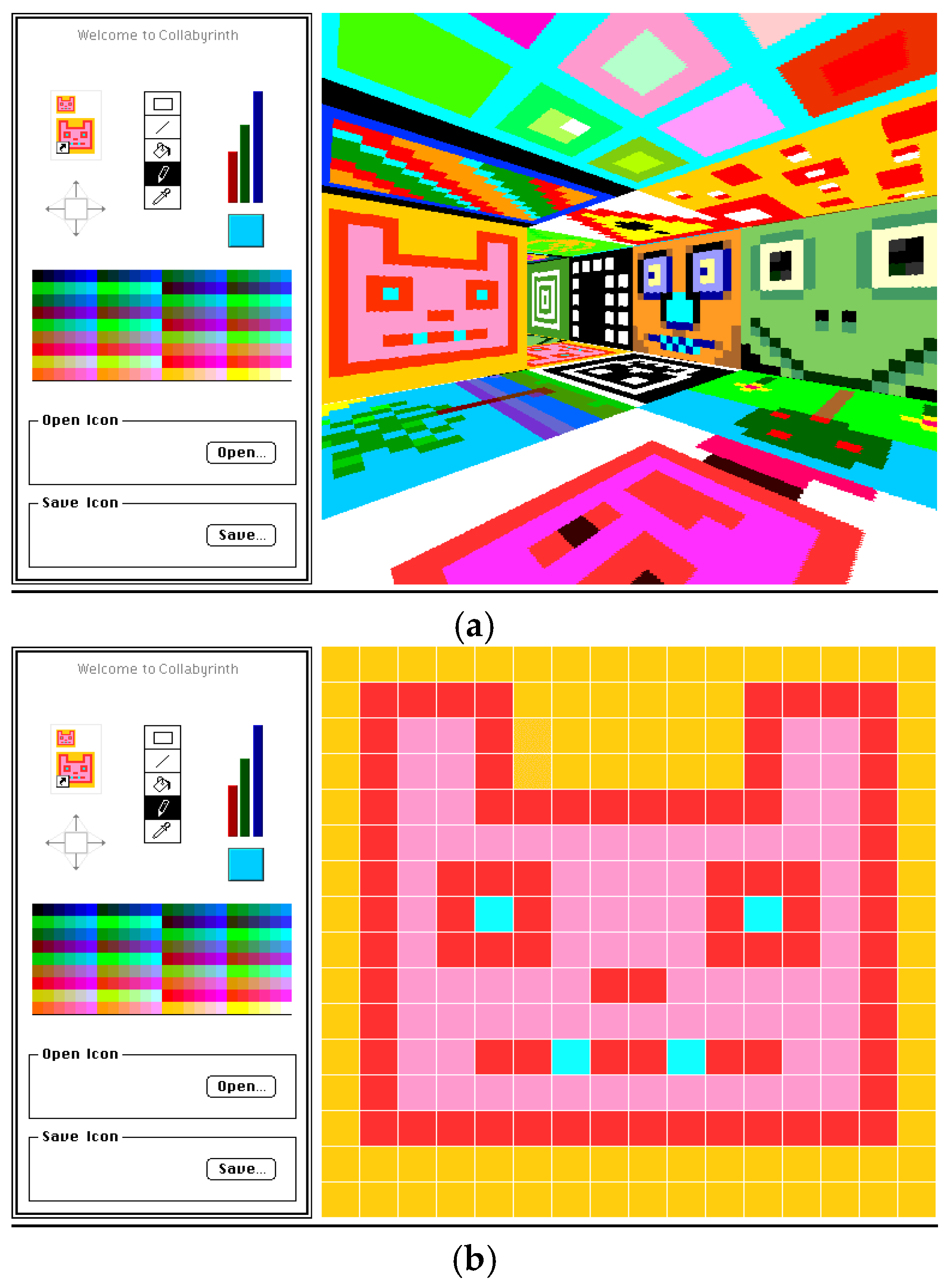

Collabyrinth (

Deck 2003), or the obscured convolutions of external data that were extracted from their native environments and gathered as fragments in

We Feel Fine (

Harris and Kamvar 2006). ODAs are filled not only with data, but also with relationships that exist between two or more parties. Therefore, ODA is also a type of relational art. Relational art is founded by the interrelations of mankind, and is an art that extends from the world of art towards individuals in society. These works are not just about art; rather, they are about mankind (

Freiling et al. 2008, p. 130).

Open Database Arts do not generally say much about the ideas of the work itself, nor do they actively express themselves. Instead, they mainly reach out for possible answers or meanings through indirect methods. Hence, an ODA must constantly update its external data in every appearance it makes for the viewers to read these data and to further improve their understanding of the work and the external data. Thus, any viewing of the external data will simultaneously involve viewing of the ODA; conversely, when one reads the ODA work itself, this must also involve the reading of external data. This is because the work itself is essentially constructed through the interactions of three dynamics between the work and external data: the dynamics of the text, the dynamics of the meaning, and the dynamics of the work’s structure (

Hsu and Lai 2014). While the work and external data may appear on different place or internet address, these are in reality inseparable and constantly interacting with each other; in other words, ODAs indirectly express themselves through others.

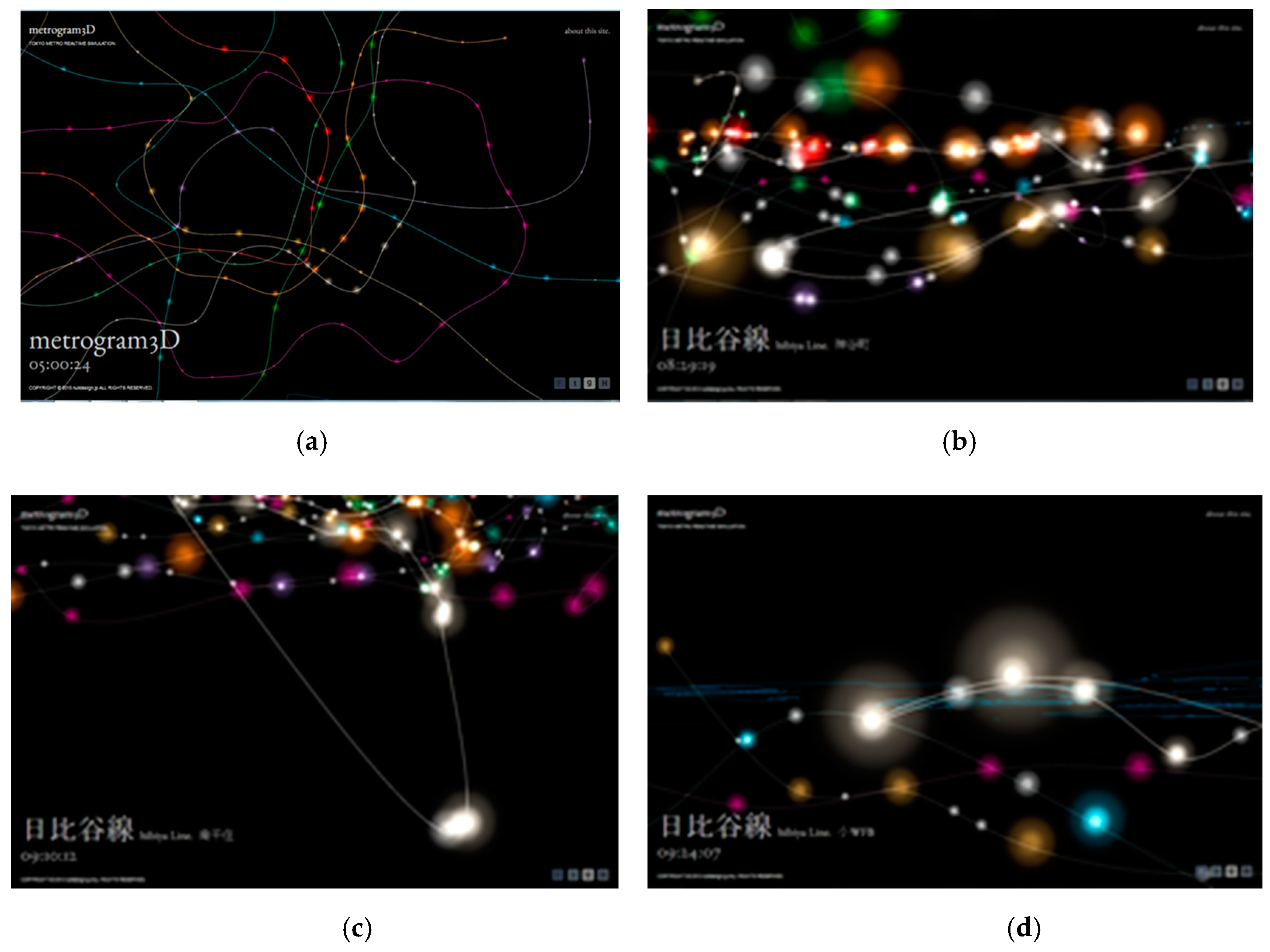

Strictly speaking, the

expression of self through others that is mentioned here involves a type of detour. As shown in

Metrogram3d (

Koi 2014), the work presents itself through others’ movements. The dazzling, moving spheres not only symbolize individual trans’ motion, but also build the connection among the viewer, artwork and the train’s physical movement in a timely manner. The import of external Tokyo metro transit data as content, followed by transformation or intertextualization, then visualization, is an approach in which the work does not directly show itself; a distance is thus created from the work through detours. The work ultimately discovers itself in detours

in-between the multitudes of others and the work, through this indirect approach. In other words, ODA works express themselves through detours.

The French philosopher François Jullien has given a profound exposition on the concept of detours (

Jullien 2000). According to

Jullien (

2000), by distancing oneself, one is then able to see one’s self more clearly; this is why Jullien reflects on Western culture through an understanding of Eastern philosophy. From ancient Chinese books, he discovered that since ancient times, the people of China often used indirect language to describe their views on objects and matters, thus achieving the desired effect through metaphors; this is precisely what is meant by a detour.

Jullien (

2000) discussed the effectiveness of expressions through detours in his book,

Detour and Access. Detours refer to indirect expression, and imply a winding and uncertain path; on the surface, it may appear that this would not be as effective as direct expression. However, the true strength of detours comes from the progressive deepening that occurs throughout the development of an affair, without leaving any signs or traces. A detouring pathway or method avoids direct confrontations, thus reducing conflict or resistance, and conversely reaches a realm that is beyond that of direct expression.

Jullien (

2000, pp. 345–46) said:

The value of detour lies in its capacity for unfolding. By deploying a succession of phases—like the succession of scenes here—it gradually opens up reality; and the continuous concatenation to which it gives rise enables us, by accompanying it, to immerse ourselves in it: not to seize hold of it all at once, as direct expression purports to do, but gradually to become imbued with it, to establish a relationship with it, to embrace its development, to enter into its inner depths and vitality, and thereby experience its at-once infinitely diffuse and all-encompassing nature as atmosphere (here, one of desolation) and globality (as opposed to generality). A scene-landscape is described, yet we enter a world; this requires a path. It is detour that gives access.

From the previous passage, it is known that the true value of detours is in its ability to progress matters through gradual permeation, to ultimately venture into the deepest realms of the truth, and to enable a proper appreciation of its deeper meanings. Detours are not intended to misdirect, but rather to refer back to one’s self in a circuitous manner, to ultimately

enter or reveal the intended matter. Hence, revelation is the other side of detours; in other words, detouring is required to truly reveal a matter. A detour may appear to lead one into the distance, but its true objective is to refer back to one’s self. Detour has a profound sense of process, but as it is a process of change, it does not include any processes that may have an

inevitable result. In other words, detour is a process without a predetermined destination, but rather it progresses with change to ultimately bring about entry.

Jullien (

2000) is of the opinion that detours possess the ability to progress and connect; therefore, detours possess profundity, broadness, and inclusivity, and provide the possibility for entry and revelation.

Looking back at ODAs, the works are performed indirectly through others, and gradually come to life through a long and winding road to finally reveal the work itself. In other words, ODAs also reveal and bring themselves into reality through detours. Detours create distance between things; through this distance, which is in-between the work and the external is drawn out. The distance that is being referred to here is not a physically measurable distance, but rather the point of focus. As the data imported into ODAs vary greatly, it is as though these data have passed through various channels, and each of these different channels could bring in different kinds of texts. Every bit of information maintains a certain connection to the work, from one piece of information to the next.

The work is a direct reflection of whatever the data happens to be, and the data that exists within the work will determine the content of the work. Once the data has been linked into the work, there is no longer any distinction between the internal and external; at that very moment, the work and external data are unified as one. The links with the work form the relationships of ODAs, and also that which is in-between the work and the external texts. During the period in which the ODA work is being performed, it continually presents itself through that which is in-between the external data and the work. These relationship between the two entities could be seen as the product of ODAs, as these relationships were created from the operation of the ODA’s programs. Amongst the multitude of moments within the work, these relationships between the work and external data are weaved by the continued operation of the work.

The narration frequency of ODAs are not always the same, as some of the ODAs will continually update their data at specific intervals according to the settings of their programs, while others will continuously collect data without pause, and the state in which each text is imported into the work and that of the narration also have limitless variations. Therefore, each update of the data will cause the relationships between the external data and the work to change continuously. Furthermore, the process of these continual changes and corrections will continuously reveal the different aspects and faces of the work’s content; therefore, a sense of self-renewal is also implicit in these works. As the external data changes, different relationships are continually created and go on to create different

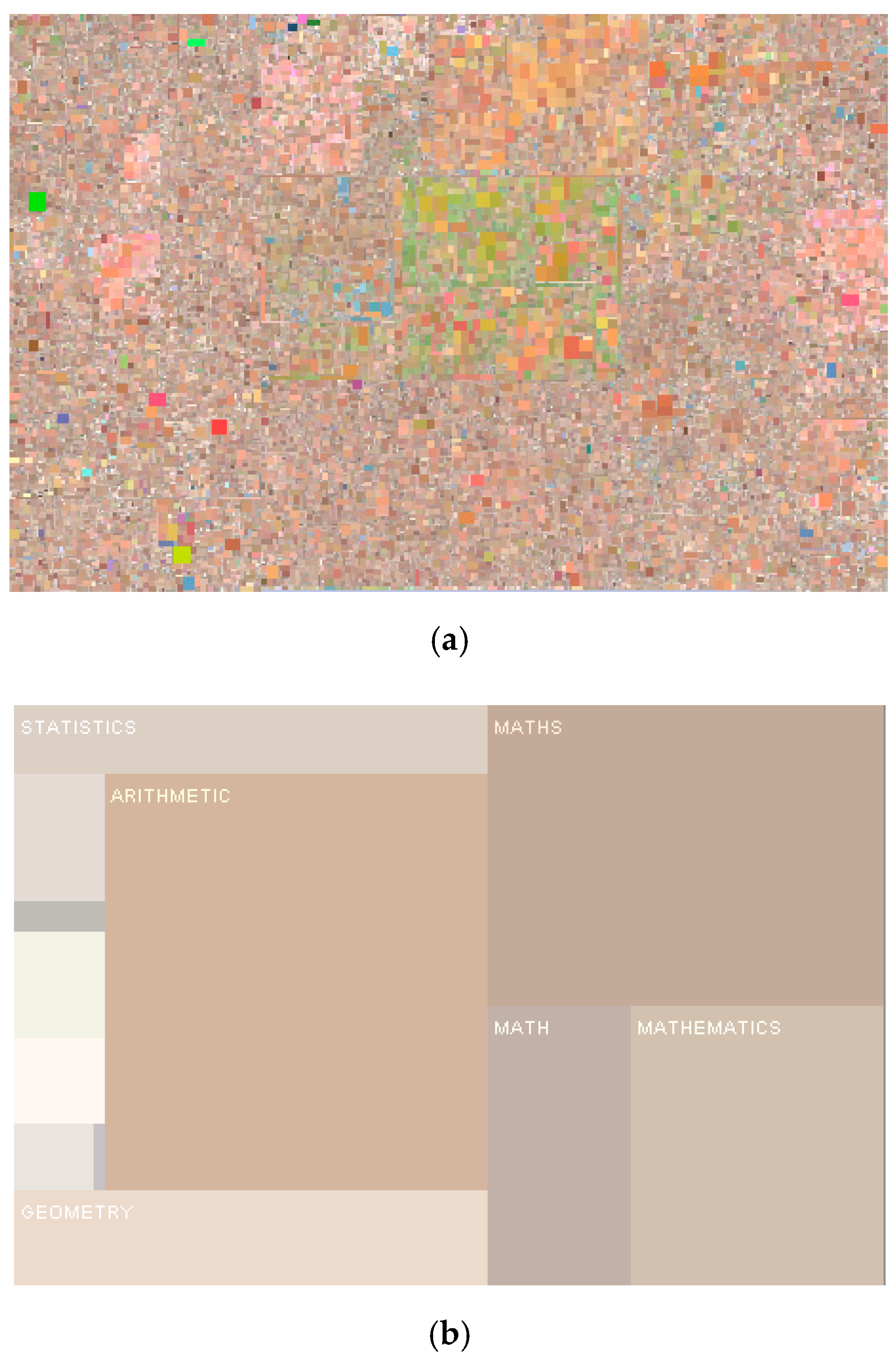

in-betweens. Some of these relationships are visible and traceable collaborative constructions, such as the drawn lines in

Swarmsketch (

Edmunds 2005); some relationships are only temporarily visible, such as those in

Collabyrinth (

Deck 2003); other relationships are very faint and barely noticeable, like in

Color Code (

Wattenberg 2005), where every color block is averaged from the colors of a multitude of images, making it hard to sense the connections between each color block and the original images. These relationships are the foundations of the work that continuously support the creation of an ODA, as ODAs are based on relationships. Since an ODA’s program will continuously update its data, these

in-betweens are constantly in flux, and the work is consequently framed within these dynamic relationships.

The ODA artist determines the settings of the ODA’s computer program, while the program determines the creation of the work’s content through retrieval operations; an ODA is only able to reveal the self of the work through a detour mode of action, through others. ODAs are not limited by fixed content and continually update themselves; each appearance of the work is simply another link in an endless chain. As a consequence, the viewing of an ODA is in actuality a process of sensing the “becoming” of a work.

4.2. In-Between That Which Is Shown and That Which Is Not

“Every actualization constitutes a limitation, for it excludes all other becoming” (

Jullien 2004a, p. 42). Therefore, any realized matter will become fixed and restricted. Conversely, that hidden and unfinished state prior to realization possesses potential as it has not been restrained, and is free to move in any direction of change. If a work with a visually fixed appearance is the epitome of solidity, then an ODA is a work that is loose and unbound with gaps that still remain; it is through these gaps that an ODA gradually seeps through and makes itself known.

If a visual image is absolutely complete, then one should able to obtain satisfaction through a single glance of the image. Conversely, an incomplete image leaves gaps that are to be filled by the imagination; visual images or data that have not yet been shown by the program lie in a state of uncertainty and remain in continued development, and are thus shrouded in mystery and hidden promise. This subtle state of not yet appearing conceals possibilities for visual development and the viewer’s imagination. Thus, this state is able to contain change, and possesses the potential for development. The subtlety of the not-yet-appearing state is transformed into a real experience and an apparent fact when it is finally revealed through visualization. This is about a change in view; between every update, in its not-yet-loaded state, the ODA creates a moment of pause and expectation. Analogous to breathing, the import of content is akin to inhalation, while the release of content and the addition of gaps are akin to exhalation; that state in which content has yet to be imported into the work is much like the transition between breaths, which can be brief or extended in time.

It is the states of appearance, not yet appearing, and expectancy of ODAs that makes them highly compelling as artworks. In particular, the concealment and appearance of the external data of retrieval ODAs implies a realization and denial of visualization, as well as the entrance and departure of the authors of the external texts. External texts and the authors of these external texts continually enter the work according to the program’s frequency of retrieval; these are presented within the retrieval ODA’s perspective, thus becoming integrated in the work. These may become unlinked by the program, or deleted by the authors of the original text, thus departing from the work. This process of entering and departing continues to proceed until the program has announced its end.

Appearance and not yet appearing are two moments that are acutely dependent on each other and are bound to one another, and thus they cannot exist independent of each other. The state of not yet appearing acts as a prequel that constructs the common roots of the work, founded in that which is not visible; a multitude of changes are thus developed. Any moment realized in the work is a process that is created from the interactions between these two entities; no moment is able to exist independently of these as they are always present and persisting within the work. The alternating appearance of these two moments are due to the operation of the internal existential logics of these two entities, which proceed according to the rhythm that is set by the program. This forms the tension of the work, and enriches the entirety of the ODA. ODAs retain this unique meaning through the continuous renewal of tension, and discover themselves through this continued tension. The depth of the work comes from its innate elasticity that enables it to appear or conceal itself in a timely manner. Through its appearance or the state of not yet appearing, an ODA is always poised to change.

The moment just before an update is imminent signifies a visual change, a renewal of the data, and the departure of the external data, with the voices of the original authors concealed within. This is immediately followed by the wait for the clarity that comes from the next moment. By developing further in this direction, the imperceptible is once again captured and converted into the perceptible. The ODA at this moment serves as an intermediary that captures the imperceptible (distant texts) through the perceptible (the frame of the ODA work) to allow for viewers to perceive the existence of things that are distant. ODAs are not simply limited to the visual; instead, they open up the world using the internet as a channel to bring in different feelings. “Dynamism” is thus generated through change, and feelings are sparked through “dynamism”.

An ODA is completed only after the processes of change of its various moments have ended. An ODA expresses itself through change. The uncertainty presented by change progressively reveals the self of the work and leads to the origins of the work. In summary, change is one of the necessary factors of an ODA, and it is the driving force that drives the concealment and uncertainty between appearance and the state of not yet appearing.

4.4. In-Between the “Here” and “There”

Our journey from the in-between has formed uninterruptible and unstoppable loops, one after another, that transcend the boundaries between cultural products and artistic products. The important point to take away is that ODA works may either be a temporary shelter or an eternal home for these external texts that are being circulated through various contexts. In summary, the in-between that connects external texts with ODA works is virtual and constantly in flux.

As ODAs are a type of work that communicates with the external, to understand ODAs, it is necessary to understand the processes through which these works are regulated. In an ODA, the original contexts of the external texts are not superfluous; rather, this is where a portion of the meaning lies. Furthermore, ODA works are indicative by nature, and one will always be allowed to remain within the narration of these works. Within this categorization of artworks, detours (indirect expression through others) and revelations (to express oneself) exist simultaneously: the import of external data and limitless renewals is a detour to express one’s self; within these detours, one also finds entry and departure.

The implementation of ODA works is performed through detours. Through the detours of others, an ODA allows for everything to remain in flux, reflects on the issues of art through undetermined modes of thought, and enables the work itself to remain in a state of limitless renewal. The special character and uncertainty that comes from having content that is “waiting to be filled” forms that which is imaginary, obscured and concealed, as well as that which is real, exposed, and open of ODAs; these also form the operational mechanism of the work itself. Although ODA works only appear to provide a frame, without any active behaviors or expressions, they constantly change, create, and express themselves over time. The viewer is thus able to “follow the real in the tension of its constant advent” (

Jullien 2000, p. 348).

Admittedly, there are many in-betweens in the detouring execution of an ODA, such as that between the others and the work, the various others, the imported external texts and the original contexts of the texts, and the perceptible and the imperceptible. ODAs also have different kinds of in-between, such as “that between two entities”, “that between two extremes”, and “entre immanent”. These in-betweens are indicative of the different levels and modes of participation. Further, these in-betweens may have come about by accident, and these may also be concealed. In short, until the program of an ODA has announced its end, an ODA will continually appear or disappear within the realm of the in-between.