1. Introduction

This study emerged from an observation: Social networking sites (SNSs) claim emphatically (and frequently) that they are platforms for authenticity. What is odd, we thought, is that these sites issue their authenticity proclamations as rebukes of their competitors’ inauthenticity. Snapchat, for example, boasts about its carefree spontaneity, set against the identity straitjackets it says are imposed by rivals like Instagram. Google+, likewise, has promised to restore the audience-specific intimacy of the offline world, which—the service claimed—Facebook’s one-big-audience model had badly undermined. In a parallel sense, plucky upstart Ello positioned itself as the anti-commercial alternative to the ad-tech data-hoovering of competing apps. We observed, in other words, a battle for the mantle of authenticity, one waged against predecessor services.

To explore that dynamic, this study tracked appeals to authenticity over time, in the promotional materials of leading social-networking sites. Using the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine, the public-facing websites of major English-language SNS platforms—beginning with Friendster in 2002—were sampled at six-month intervals, with marketing language and visuals examined for authenticity claims. Statements from CEOs, official videos, and app store copy were used to supplement the catalog of half-year-interval website screen-captures.

We found that nearly all SNSs invoked authenticity—directly or through language like “real life” and “genuine”—in their promotional materials. What stood out was the profoundly reactive nature of these claims, with new services often defining themselves, openly or implicitly, against legacy services’ inauthenticity. The pattern was set in motion when Facebook began to promote its single-identity, real-name policy as a badge of authenticity. This nominal notion of the authentic set the stage for rival claims, often issued with Facebook as explicit foil. In place of real-name consistency, competing services embraced a variety of alternatives, articulated in real-time, creativity, audience-segregation, anonymity, spontaneity, anti-commercial, and emotional terms. A recurring marketing strategy, in other words, has been to call out Facebook’s phoniness by substituting (and touting) some other, differently grounded mode of authenticity.

To make sense of this pattern, the article makes three overlapping arguments. The first one is broad, and informs the other two: (1) Social media scholars should take authenticity more seriously. The reason that services routinely proclaim themselves as sites for authentic self-expression, after all, is that many users profess a commitment to presenting themselves authentically, and to seeking out others who seem to share that commitment. The second point is that (2) authenticity as an ideal is fundamentally unstable, by definition. As a claim or badge, the “authentic” is always relative to something else, and therefore susceptible to the charge of phoniness—especially if strategy and calculation can be identified. This instability fuels an insurrectionary dynamic, in which new and “genuine” forms get proposed in place of the older and now-discredited claimants. This social media one-upmanship, we argue, is an expression of that core instability—in fractal form. Our third argument is that (3) this dynamism has produced an array of competing authenticities—seven in all, each exemplified by a major service. Our findings show that the foregrounding of performance—a pervasive feature of everyday life, but newly visible on social-media platforms—provides the main rhetorical fuel for dismissing rival sites. Since the affordances of social sites, even those touting evanescence or anonymity, make them vulnerable to similar charges, the cycle gets replayed with numbing regularity. Upstart services like Beme or Peach continue to define themselves as refuges from the pervasive inauthenticity of incumbent sell-outs.

2. Authenticity and Social Networking Sites

A growing but relatively small number of social-media studies place authenticity at their center. A much larger proportion of papers, books and book chapters on social media and the self touch on authenticity themes in passing. Even among the core studies, however, the treatment of the authenticity ideal has tended to be flat and suspicious.

What the existing research does help capture is the sheer variety of meanings that social media users assign to the “authentic.” Taken as a whole, this literature highlights a number of different authenticity markers—criteria that users employ to judge what counts as authentic. This diversity of meanings, in our view, is a reflection of the context-dependent nature of authenticity, the sense in which the ideal is “a localized and temporally situated social construct that varies widely based on community” ([

1], p. 124).

2.1. Authenticity Markers

The most common marker for authenticity identified in these studies is consistency, though researchers have distinguished at least three distinct kinds. Authenticity is achieved, by one criterion, when a user’s Facebook or MySpace self matches their “real world,” offline self [

2,

3,

4,

5]. Consistency can also be warranted by cross-platform uniformity, when a user’s many profiles align in theme and presentation [

6]. Consistency, finally, can stand in for the authentic in chronological terms: maintaining a stable profile over time [

4,

6,

7,

8]. The inauthentic user, by this measure, strays too far from their typical self-presentation. As one of Uski and Lampinen’s informants put it, “You can’t just put only some Finnish polka there if in reality you listen to metal” ([

7], p. 456).

Another frequently invoked authenticity marker is apparent spontaneity: a social-media presence that comes off as effortless, carefree, and/or indifferent to audience reception. To be deemed authentic, posts or photos must seem like they were not fussed over ([

2]; [

5], p. 136; [

7], pp. 454–55; [

8,

9]; [

10], p. 5; [

11], p. 2000). Davis, in her MySpace ethnography, found that her subjects were eager to maintain an “impression of spontaneity”—to conceal, that is, evidence of forethought and planning. “An authentic self,” writes Davis, “is a self that appears to simply be, rather than a self that is accomplished” ([

8], p. 1967). One labor-concealing device identified by Davis is “apathetic framing”: A MySpace user, for example, titled a self-focused post, “waiting for work to be over” ([

8], p. 1972). Likewise, Marwick and boyd’s Twitter study revealed that many subjects judge “consciously speaking to an audience” to be inauthentic. As one respondent explained in a Tweet, “it’s worth it 2 me 2 lose followers 2 maintain the wholeness/integrity of who/what/how I tweet” ([

1], p. 119).

Existing studies have also reported that sharing (carefully selected) personal details is a method for cultivating a sense of authenticity [

1,

12]. By this criterion, placing tidbits of curated intimacy fosters a relatable, everyday persona, even for “influentials” with high-follower counts. As Duffy and Hund observe, many fashion bloggers pepper their Instagram feeds with children and pets; one prominent blogger captioned a photo of her dog near a hairdryer, “Someone is in a fight with the blow dryer” ([

12], p. 7). Similarly, Marwick and boyd’s research on celebrity Twitter practices identifies how the famous supply their fans with backstage, intimacy-establishing glimpses of their lives, as with this quoted Tweet from Mariah Carey: “@jasminedotiwala just sang the Vegas remix of ‘these are a few of my favorite things and did a little dance in a terry cloth robe’ hilarious” ([

9], p. 145).

A final authenticity marker identified in the literature is amateurism [

12,

13,

14,

15]. Whether deliberate or not, the impression of an unrefined passion helps to furnish an aura of authenticity. Tolson’s study of YouTube makeup vlogs points to the underlit, grainy “realness” of vloggers’ videos as signals of contrast to the traditional television star [

13]. Evidence of real-time recording, unscriptedness, and even exposure of the production process all connote an anti-professional sense of the real. As Tolson, referring to a vlog, noted, “It is not just then that the production is amateurish, it is that she makes a transparent virtue of this” ([

13], p. 281). Duffy and Hund’s fashion bloggers, too, sprinkle their Instagrams with blurry selfies, mid-range brands, and self-deprecating captions—none of which is likely to appear in fashion magazines [

12].

Lobinger and Brantner, in their study of selfie authenticity, identified all four of these markers in their subjects’ varied reactions [

16]. They clustered their participants into one of four groups, each with its own distinctive criteria for what counts as an authentic selfie. For one group, evidence of filters and editing is disqualifying (amateurism); for another, the absence of obvious posing or an extended arm turns out to be the key factor (spontaneity). The third group judged authenticity by the perceived realness of the situation; anything apparently “staged” was described as insincere (personal details). The fourth and final group measured authenticity by photographic technique: seemingly amateur composition registered as more real than “arty” or professional-seeming shots (consistency). Lobinger and Brantner, in effect, have stumbled upon the

variety of authenticities—the way in which understandings of social media “realness” compete and co-exist ([

16]; see also [

17], pp. 148–50).

2.2. The Social Construction of Authenticity

Much of the literature places an understandable emphasis on the strategic and performative nature of social media self-presentation, including our own previous work. The claim is fair and supported by the evidence; authenticity really is performed, given the conscious effort that posting requires, compounded by the pervasive culture of self-branding. Still, the cumulative impression the literature gives off is of debunking and dismissal. By repeatedly calling out the constructedness of users’ authenticity claims, researchers may inadvertently downplay those claims’ power and resonance.

Like most researchers, Hess portrays authentic self-portraiture on social media as a discursive achievement [

10]. Haimson and Hoffman, likewise, describe authenticity as “an artificial category” [

4]. Davis, citing Goffman, defines authenticity as a “

seeming spontaneity of action, interaction, demeanor and selfhood” ([

8], p. 1967; emphasis ours). Or consider Uski and Lampinen’s conclusion: “In stark contrast to the way authenticity is popularly understood as something straightforwardly true and unintentional, our study makes apparent how authenticity is ascribed” ([

7], p. 461). Banet-Weiser, in

Authentic™, takes the point a step further, asserting that “we take it for granted that authenticity, like anything else, can be branded” ([

18], p. 13). Tolson, referring to vlogging authenticity, even feels compelled to include the aside, “if it is to be perceived as such” ([

13], p. 286). Marwick and boyd typify the scholarly consensus: “Of course, authenticity is a social construct” ([

1], p. 119).

Taken as a whole, then, the literature assumes a knowing, even jaded posture. The message, an unintended one, is that we scholars see behind the curtain to expose an Oz-like authenticity con. We see too easily, in other words, the effort put into the seemingly effortless. However accurate, this skeptical stance discounts the ideal’s enduring purchase, as well as its shape-shifting adaptability.

2.3. Defining Authenticity

Most of the existing literature neglects to define authenticity altogether, preferring to let context and actors’ understandings do the definitional work (e.g., [

2,

5,

10,

11,

19,

20]). Uski and Lampinen, for example, provide a rich analysis of the performative dimension of authenticity, yet never pause to assign a working definition to the term [

7]. The implication is that authenticity is innate and so pervasive that it doesn’t need to be defined. Banet-Weiser, likewise, sidesteps the question: “The authentic is tricky to define. Its definition has been the subject of passionate debates involving far-ranging thinkers, from Plato to Marx, from Andy Warhol to Lady Gaga. I am not,” she admits, “offering a new definition” ([

18], p. 10). Here the term’s madcap indeterminacy (what Dare-Edwards calls the “complex concept of authenticity” ([

20], p. 522)) is the cited reason.

Of all the existing studies, Lim et al. provide the most extensive discussion of the authenticity ideal ([

21], pp. 132–35), though the authors confine themselves to the psychological literature. In another departure from other research, Lim et al. treat the authentic inner self as real and unproblematic, and focus instead on the (perhaps surmountable) challenges that social media users face in expressing their true selves.

A few studies engage the ideal’s historical emergence in the context of classic works by literary scholars and philosophers. Marwick and boyd [

9], for example, apply Lionel Trilling’s [

22] sincerity/authenticity contrast to celebrity Twitter practices. Gaden and Dumitrica’s treatment, though brief, stands out for its sophisticated account of the ideal’s roots in 18th century Romanticism [

14].

By and large, however, the research to date has left the authenticity notion underdeveloped. One consequence is that social media scholars have not taken the ideal seriously enough.

3. Authenticity and Its Discontents

Our view is that the definitional evasion and suspicion of authenticity are rooted, to some extent at least, in scholarly discomfort. The roving, constructed nature of authenticity is obvious to academics, who detect the ideal’s core contradiction: that the true and original inner self designated by the term is made, not found. Highly attuned to the self’s performative contingency and to its social conditioning, scholars rush to place scare quotes around the word, or else gleefully deconstruct its contradictions. We trip over one another to distance ourselves from authenticity claims, perhaps to reassure each other that we are not taken in. That knowing stance—of course authenticity is a construct—has the look and feel of a sneer, or at least an embarrassed smile.

The stakes are high, if only because social media is marinated in authenticity claims. Services routinely proclaim themselves as sites for authentic self-expression. Many users profess a similar commitment, and expect others to aspire too. Exposing inauthenticity, at the platform or individual level, is a recurrent preoccupation—but an exposure typically motivated by locating the real thing.

In this section, we briefly gloss the history of authenticity, with special attention to the ideal’s instability. Drawing on a rich body of work in philosophy, literature, sociology, and anthropology, we describe authenticity as both modern and reactive. Our account is indebted to Charles Taylor’s sweeping history of the self’s emergence [

23,

24], Lionel Trilling’s treatment of authenticity as a rejectionist ideal [

22], Marshall Berman’s anatomies of market dynamism and the politics of authenticity [

25,

26], and Charles Lindholm’s synthetic studies of these and related works [

27,

28]. To gesture at the crucial contradictions within authenticity’s 20th-century offspring—in advertising, self-help, student radicalism, New Age spirituality, celebrity culture, and management theory, among other domains—we reference the loose tradition of work on the history and sociology of the therapeutic ethos. Figures like David Riesman [

29], Philip Rieff [

30], Daniel Bell [

31], Arlie Russell Hochschild [

32], Warren Susman [

33], Erich Fromm [

34], Jackson Lears [

35,

36], Christopher Lasch [

37,

38], and Eva Moskowitz [

39], taken together, chronicle a new yearning for individual self-fulfillment that was, however, tied up in commerce and self-promotion.

3.1. The Modern Roots

Authenticity, as an ideal expressed in philosophy and literature, emerged in 18th-century Europe. But a number of broad-scope and interwoven developments, all of them linked to modernity, preceded its full articulation: the slow recession of belief in a cosmic order with fixed and unquestionable social roles, the countervailing idea of individual selfhood (with its claims for inner depths, equal dignity, and self-responsible freedom), the rise of capitalism and wage labor, and the growing authority of science and Enlightenment appeals to rationality. The key point is that these facets of modernity were both preconditions for, but also provocations to, the ideal of authenticity. Another way of saying this is that authenticity was both a product of, and a reaction against, modern life. In this respect authenticity is like orthodox religion, unthinkable without some new, modern other—in this case, secularism.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, the Geneva-born 18th-century philosopher and novelist, furnished the first full expression of authenticity. He articulated each of the ideal’s major elements: (1) the notion that we all have an original and unique self, one which (2) resides inside us but must be (3) discovered by “finding” ourselves (often in the contemplation of nature), and (4) which we are called upon to express, even in (5) defiance of social conventions. In the late 18th and 19th centuries, re-articulations—including the application of the originary idea to linguistic communities by the German philosopher Johann Gottfried Herder—accreted into the various artistic and literary currents of Romanticism. The movement’s celebration of emotional intensity, untamed nature, aesthetic experience, a pre-modern “folk” past, and (in some versions) the nation was—in distinctive but overlapping form, from Goethe to Byron to Whitman—an explicit rebuke to Enlightenment rationality, the ethos of science, and the new industrial capitalism. By the early 20th century, against the backdrop of urban anonymity and the sped-up pace of life, ordinary people in Europe and North America began to yearn for authentic experience and self-fulfillment. The stage was set for the ideal’s widespread, and scarcely questioned, entry into the moral fabric of Western societies: the call to become what one is. Rousseau’s plea in

Reveries of a Solitary Walker—”Let me give myself over entirely to the pleasure of conversing with my soul” ([

40], p. 7)—had become the unwritten guide to living well.

3.2. Authenticity as a Reaction

A key feature of the authenticity ideal is its reactive nature. Rationality, the cash nexus, black Satanic mills—above all, the quintessentially modern idea that other people are a means to one’s own ends—these are the things that authenticity reacts against. Another way of saying this is that authenticity is a response to the instrumentality of everyday (and not just economic) life. A working definition of the ideal rests on this relational dimension: Authenticity is a reaction to perceived inauthenticity.

This definition—unapologetically circular—points to a second quality of the authenticity ideal: its instability. The perceived inauthentic that the ideal reacts against can appear in overt forms, like Wall Street-pleasing job cuts, parking-lot despoliation, or the bureaucrat’s reference to citizen-subjects as long strings of numbers. But the inauthentic can also appear

covertly, wrapped in the cloth of the seemingly spontaneous. It is this second type, what has been called “calculated authenticity” [

41], that fuels the ideal’s cat-and-mouse dynamism. The ubiquity of calculated authenticity in the promotional industries and in everyday life has as its byproduct, in the face of exposure, an increasingly frenetic search for the genuine article.

Lionel Trilling’s 1971

Sincerity and Authenticity is centered on this insurrectionary dynamic [

22]. The book builds a sequential contrast between sincerity—the public duty to present yourself as you are, an early-modern social norm fit for an emerging market economy—and twentieth-century authenticity, with its resolutely individualist rejection of society. The ideals are superficially similar, but the former in fact motivates the latter: “Society requires of us that we present ourselves as being sincere,” Trilling wrote. “...we play the role of being ourselves, we sincerely act the part of the sincere person, with the result that a judgment may be passed upon our sincerity that it is not authentic” ([

22], pp. 10–11). Authenticity is an escalating riposte to modern society’s pervasive phoniness, from the glad hand to the promotional smile. According to Trilling, performed sincerity calls forth an array of rejectionist answers including irony (as exemplified by Oscar Wilde and Friedrich Nietzsche), the fiery prometheanism of protest, and even madness.

That baggy “therapeutic ethos” tradition—Susman, Lears, Rieff, Lasch, and the rest—catalogued the many interminglings of American consumer culture with the quest for personal fulfillment. Advertising and the self-improvement industries, by the early 20th century, had already hitched themselves to the yearning for authentic experience. The self-help literature of the 1920s and 30s, for example, instructed readers to stage-manage an attractive front, through grooming, dress, and a charming personality. As Susman summarized the new message: “One is to be unique, be distinctive, follow one’s own feelings, make oneself stand out from the crowd, and at the same time appeal—by fascination, magnetism and attractiveness—to it” ([

33], p. 289). The way to win friends and influence people, Dale Carnegie advised his readers, is to “become genuinely interested in other people” and to “make the other person feel important—and do it sincerely” ([

42], p. 105). If the message was something like

be true to yourself—it is to your strategic advantage, then the “cosmic defiance”—the rejectionist disgust that Trilling documents ([

22], p. 99)—makes sense: The “authentic” had been colonized by calculated self-promotion.

This marriage of strategy and self-fulfillment was renewed across a range of 20th century cultural phenomena: in pop psychology [

43], liberal Protestantism [

44], celebrity worship [

45], the counterculture [

46], the student New Left [

47], the human-potential movement [

48], management literature [

49], craft manufacturing [

50], and self-help [

51]. Even the rejectionist strands of authenticity, like leftist protest culture [

46], get peddled back to us. The now-pervasive injunction to create an authentic “self-brand” is only the latest example of a recurring dynamic.

As Trilling explained, the response to the “coercive inauthenticity of society” is to flee to deeper kinds of authenticity. When these, too, are returned to the promotional fold—when punk themes adorn billboards—the search for an untainted authentic begins anew. The engine of the cooptation cycle is the market itself—which is merely answering our yearning for the authentic in an inauthentic culture. The very logic of competition and profit-seeking, as Marshall Berman argued, has an antinomian character [

26]. Capitalism’s Dionysian core is its ferocious appetite for profit alongside its roving agnosticism about the source. Berman, drawing on a strand of Marx’s analysis of capitalism—its propensity to melt solids into air—stressed its “constant revolutionizing, disturbance, agitation”; the market “needs to be perpetually pushed and pressed in order to maintain its elasticity and resilience” ([

26], pp. 117–18). Profit-maximizing firms search out air pockets of intact meaning, even

especially market-allergic subcultures and artistic movements whose self-anointed authenticity depends on the contrast. “[M]en and movements that proclaim their enmity to capitalism,” Berman observed, “may be just the sort of stimulants capitalism needs” ([

26], p. 118).

Here is the source of what we are calling authenticity’s

reactive dynamism. The range of authenticity markers—from folksy word choice through to armed leftist guerrillas—is marketing gist for money-making firms. The companies’ tight embrace then suffocates out the sense of the authentic, leading to a fresh contrast with the now-tainted original. That too proves attractive to marketers, and the cycle repeats itself. As Arlie Hochschild wrote, “the more the heart is managed, the more we value the unmanaged heart” ([

32], p. 192). Born in reaction to modernity’s instrumentalism, the authenticity ideal is, and for the same reason, susceptible to promotional uptake. As a result, the ideal is fundamentally unstable and nomadic.

Our hunch was that the social media ecosystem, starting with Friendster, might be a laboratory for this brand of reactive dynamism. All the venture–funded social-networking start-ups since, after all, were launched as profit-seeking platforms for self-expression—authenticity as a commercial strategy. That backdrop—the data-mining and the ads—represents a source of built-in tension: one person’s expressive self-fulfillment is another’s profit margin. But the main reason social media sites are a petri-dish of calculated authenticity is the performative control they furnish to their users. Most services are asynchronous, and thus permit, for example, the protracted crafting of seemingly offhand posts. In the same vein, most sites and apps furnish some editing control, by way of photo filters or readymade graphics or custom emoji. The point, for our purposes, is not that these affordances render social-media performance inherently inauthentic. The implied contrast to spontaneous face-to-face talk is undercut, at the very least, by all the impression management that everyday conversation requires. The point, instead, is that social-media performative control—given that most users are well-versed in its arts—draws special scrutiny to authenticity claims. We are all, in other words, artifice detectives on social media: Isn’t that #nofilter Instagram actually a Valencia fake? The line between self-promotional staging and authentic self-expression, on Facebook and the rest, is especially blurry. As a result, the social-networking economy is primed for authenticity one-upmanship.

4. Methodology

In order to trace social-networking sites’ authenticity appeals over time, we turned to the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine, which provides a searchable archive of regularly cached, time-stamped web pages dating back to 1996 (“491 billion web pages saved over time”). We selected a broad sample of social networking sites, based on services’ U.S. peak popularity and general-interest orientation, from 2002 (when Friendster was founded) through to 2014 (Ello’s launch). In all, we analyzed eleven networks: Friendster (2002), MySpace, Facebook, Twitter, Tumblr, Instagram, Whisper, Snapchat, Google+, Yik Yak, and Ello (2014).

1 For each service, we screen-captured the homepage and any “about” or “site tour” pages, beginning with the earliest site caches indexed by the Wayback Machine and in subsequent six-month intervals up through July 2016. For example, our first capture of Facebook’s homepage (at thefacebook.com, its original URL) was time-stamped to 12 February 2004; we collected 23 additional homepage views (along with related “about” materials) through to 15 July 2016, when our analysis concluded. This collection of homepages was supplemented by other promotional materials, including founder comments to the press, company blogs, and overview videos posted to YouTube.

The authors conducted a qualitative analysis of these materials, with special attention to authenticity-related claims. We identified themes and patterns in each site’s landing-page pitch, as these touched on identity and self-expression. A 2013 Google+ site-tour page-capture, for example, invited users to take up the service with three authenticity call-outs: “Express yourself in words and pictures,” “Share details with the right people,” and “Be yourself all across Google” [

50] (see

Figure 1). We analyzed the language, accompanying imagery, and additional text with the aim to distill and label Google+’s distinctive authenticity appeal. We employed a similar procedure to identify patterns across the other ten services’ homepages, as they evolved over time and in comparative perspective.

To test whether the reactive dynamics we identified in the legacy sites continued to operate, we decided to include a handful of more recently launched services. We examined three upstart services that generated press attention in 2015 and 2016: Peach, Beme, and Plag. We conducted a similar analysis of these apps’ promotional materials, including videos, blogs, homepage language and app-store screenshots.

5. Findings

Beginning with Friendster’s site in late 2002, our six-month-interval screenshots revealed a contest for authenticity, one rendered in time-lapse terms. Two facets of the patterned competition stood out: first, the sheer variety of authenticity claims issued by the rival services, from boasts of spontaneity by one to filter-free sharing by another; and, second, the consistency with which these claims cited predecessors (Facebook above all) as their inauthentic contrast. We witnessed, in other words, a cycle of reactions, one that—to judge by the most recent services’ marketing—remains in motion.

The authenticity contest did not, however, take hold immediately. The early services (Friendster, MySpace, and Facebook) initially touted the rewards of connection over those of self-expression. Facebook, as the service gained on MySpace, began to trumpet its single-identity, real-name virtue—a profession, in our language, of

nominal authenticity. We then identified a parade of competing authenticity types, each formed in reaction to Facebook. The micro-blogging site Twitter, for all its promotional shape-shifting, cast itself as the guardian of

real-time authenticity; the marketing message was that the real inheres in fleeting and to-the-minute Tweets, not by way of a persistent, name-and-profile identity. The blogging service Tumblr, too, began to define itself against Facebook’s single-identity norm, but with a stress on artistic self-expression—what we have called

creative authenticity. Google+, the search giant’s ill-fated Facebook rival, constructed its claim to genuine identity by analogy to the “real,” offline world, where we disclose who we are to carefully selected audiences:

segregated authenticity. The photo-sharing startup Snapchat took aim, instead, at Facebook’s museum-like self-curation; its evanescent alternative was packaged as

spontaneous authenticity. Services like Whisper and the college-gossip app Yik Yak proceeded to identify Facebook’s real-name ideology as the crucial barrier to honest expression; give a user a mask, on the

anonymous authenticity view, and she will tell the truth. More recently, services like Ello and Plag have reacted against the data-mining, ad-saturated experience of other social media, especially Facebook—the pitch here is

anti-commercial authenticity (see

Table 1).

The cycle keeps repeating itself. The newest apps, like Beme and Peach, stake their own claims to networked self-expression. Peach, for example, proclaims its authenticity in emotional terms—complete with “Magic Words” and a whole-hearted embrace of emoji. Authenticity is fundamentally reactive; little wonder, then, that social media sites—whose very affordances raise calculated-authenticity doubts—respond to legacy competitors.

5.1. Nominal Authenticity

Friendster (2002), MySpace (2003) and Facebook (2004), three of the earliest social networking sites with wide uptake, initially presented themselves as places to connect with friends (new and old). An early Friendster homepage, from when the service was still in beta, carries the tagline “The new way to meet people.” Friendster, according to the bold copy, is “an online community that connects people through networks of friends for dating or making new friends.” Likewise, MySpace began by calling itself “a place for friends,” and Facebook (née Thefacebook) claimed to be an “online directory that connects people through social networks at colleges.”

Without abandoning the focus on friendship networks, Facebook in particular came to orient its marketing, self-presentation, and policy around

nominal authenticity—the notion that users should present a single identity tied to their real names. Before 2007, the site permitted users to sign up with just one letter of their last names, though fake or celebrity names had long been cheekily forbidden: “Dude, everyone knows that you aren’t Paris Hilton” [

53]. In May 2007, the same month the company launched its Facebook Platform application layer, the site began requiring full names. The shift came just a few months before Facebook started its external-website data-tracking Beacon program, around the time that Microsoft’s investment valued the private company at $15 billion. This was the same period that founder Mark Zuckerberg and COO Sheryl Sandberg began proclaiming the virtues of single-identity authenticity. As Zuckerberg famously pronounced to a journalist, “You have one identity...The days of you having a different image for your work friends or co-workers and for the other people you know are probably coming to an end pretty quickly.” Having two identities, he added, is “an example of a lack of integrity” ([

54], p. 199). As the online archive The Zuckerberg Files document, the pace of Zuckerberg’s references to “genuine,” “real,” and “authentic” increased steadily over the next few years, cresting in 2011. That year, Sandberg, the company’s COO, wrote in

The Economist:As we share more of ourselves online...increasingly one voice will ring out. The use of social media is heading towards the convergence of our virtual and real selves...Expressing our authentic identity will become even more pervasive in the coming year. Profiles will no longer be outlines, but detailed self-portraits of who we really are, including the books we read, the music we listen to, the distances we run, the places we travel, the causes we support, the videos of cats we laugh at, our likes and our links. And, yes, this shift to authenticity will take getting used to and will elicit cries about lost privacy. But people will increasingly recognise the benefits of such expression. Because the strength of social media is that it empowers individuals to amplify and broadcast their voices. The truer that voice, the louder it will sound and the farther it will reach.

A few weeks after Sandberg’s article, Facebook took Timeline, its algorithmic, reverse-chronological profile page, public. The promotional page pitched Timeline as the place to “tell your story from beginning, to middle, to now,” asked users to select a “unique” banner image “that represents you best,” and promoted a new class of social apps that “let you express who you are through all the things you do” [

56].

Despite controversy and concessions, Facebook continues to enforce its real-name policy, complete with liberal use of the “authentic” descriptor. The site’s real-name explainer page, for example, states that “Facebook is a community where people use their authentic identities” [

57]. As Haimson and Hoffman document in their registration walkthroughs of the site [

4], Facebook’s “onboarding” process and policy pages are saturated with the language of authenticity.

The essence of Facebook’s authenticity claim is consistency across all three dimensions, as warranted by a real name: (1) offline/online correspondence; (2) self-presentational stability over time; and (3) even (to the extent that Facebook’s external-site logins, third-party apps, and tracking breach its walls) self-uniformity across platforms. This thin, nominal notion of authenticity is, even on its own terms, rife with contradiction. The chief tension derives from performative control: Users may consciously stage-manage a consistent self, given the asynchronous and editable nature of the site’s affordances. “Acting unself-consciously,” Silverman observes, “becomes its own kind of self-conscious exercise” ([

5], p. 136)—a paradox all too obvious to social-media audiences jaded by canned authenticity. Facebook’s performative contradiction opens up a wedge, an opportunity for rival services, who stand at the ready with competing notions of authenticity: reactive antidotes to the social media Goliath’s counterfeit variety.

5.2. Real-Time Authenticity

Twitter, the micro-blogging service launched in 2006, has consistently emphasized quick, real-time updates. For Twitter, authenticity is a product of immediacy, touted with an implied contrast to plodding, packaged deliberation. The site’s original homepage promised “instant mobile updates,” demonstrated by a refreshable list of actual, in-the-moment Tweets (e.g., “feeling really hungry. I could eat a pig right now! gotta go n grab a bite...”), with a time stamp (“2 minutes ago”) [

58]. The site was soon billing itself as a place for “exchange of quick, frequent answers to one simple question: What are you doing?”, and openly encouraged its mundane, grammar-indifferent content [

59]. “Why use Twitter?” the site asked. “Because even basic updates are meaningful... especially when they’re timely.” Eating soup? “Research show that moms want to know” [

60] (see

Figure 2).

From the beginning, Twitter invited users to adopt nicknames, opting for globe-spanning immediacy over legal-name offline tethering. For a time, from 2007 to early 2009, the site did not even prompt for names at all. The

real-time authenticity promised by the service was an implied contrast to the deliberate self-polish that characterize static-profile maintenance and even the status updates of Facebook’s recently introduced News Feed. In keeping with its mimicry of face-to-face talk, Twitter prevented users from editing Tweets. “Once it goes, it goes!” read the site’s unapologetic 2007 FAQ. No “changing text, context, spelling errors, etc.” [

61]. Editing real-time bursts of disclosure would, by implication, strip away the site’s conversational veneer.

By 2008 Twitter was touting a broader range of information “as it happens—from breaking world news to updates from friends” [

62]. The next year, as the site hit 18 million users, the homepage urged visitors to “join the conversation” [

63]. That conversation, in Twitter’s vision, broadened to include the 140-character updates of celebrities and brands. A 2011 promotional video featured testimonials from celebrities like Richard Branson, Snoop Dogg (who championed Martha Stewart’s Twitter), and an astronaut turning his camera on Earth. “Follow your interests,” the video urges. “Discover your world” [

64].

With the 2016 return of co-founder Jack Dorsey as CEO, the company reaffirmed its real-time roots. “What’s Happening” is now bannered across the site’s homepage, with Twitter-selected “Moments” (curated Tweet collections about breaking news) sharing space with prominent, buzzy Tweets [

65]. A new television ad, wallpapered with imagery from recent events (the Rio Olympics, a Trump press conference), drives home the real-time emphasis: “What’s happening in the world? What’s everyone talking about? What’s trending?” asks the voice-over. “See what’s happening in the world. Right now” [

66].

5.3. Creative Authenticity

Tumblr launched in 2007 as an alternative to Blogger and Wordpress, with a different take on the blog. From the beginning, Tumblr positioned itself as a space for creative self-expression. Founder David Karp created the site as a platform for what was already known as a “tumblelog,” a casual, free-form variant of the traditional blog. In Karp’s early definition, the tumblelog was a “new philosophy…free of noise, requirements and commitments” [

67]. The site’s original homepage described the platform as “your friendly and free tool for creating tumblelogs” [

68].

“Is Tumblr better/worse than Blogger, TypePad, FaceBook, etc.?” asked the site’s FAQ. “It’s totally different. That’s why we built it, and why love it so much” [

69]. Already the platform was featuring colorful, photo-rich blogs on the page, and—a few months later—was defining its service as a “refreshingly simple new way to share anything you find, love, hate or create” [

70]. The core message was that Tumblr is for creative people.

By the next year, the New York-based company had doubled-down on its creativity sell. “Tumblelogs,” the homepage banner proclaimed in 2008, “are the easiest way to express yourself.” The site touted the ability to “customize everything,” from “colors to your theme’s HTML markup” [

71]. By 2009, the site was directing users to a grab-bag spread on “21 reasons why you’ll love Tumblr.” The grid-like pitch, sandwiched between a pair of collages showcasing an eclectic sample of Tumblr blogs, emphasized design and visual expression. Would-be users were encouraged to check out a “Theme Garden” with “[h]undreds of gorgeous themes” —or to make “something truly original with full markup and design control.” Even the blurb explaining its medium-specific upload approach called out those forms already associated with artistic creation. “Whether it’s a thought, photo, song, quote, video, or overhead conversation, Tumblr senses what you’re sharing,” the page read, “and presents it beautifully.” The site’s support for “High-res photos” was proclaimed in the grid’s center, with a fashion/art glamour shot half-obscured by a Rothko-esque color exposure on one edge. The page, in short, left an unmistakeable (and stylized) impression of artistic self-fashioning [

72].

Going forward, the homepage dispensed with promotional text altogether, letting multi-hued screenshots of sample blogs (or, slightly later, a spread of relentlessly artsy photographs) serve as graphical stand-ins for the service. By 2012, the site’s About page was dominated by a screen-spanning curated rotation of images drawn from existing Tumblrs. Stenciled over the collection was an abstracted camera lens, encircling the curved text “FOLLOW THE WORLD’S CREATORS” [

73] (see

Figure 3). The next year, the homepage itself took on the image-carousel effect, with a new and evocative user photo swapped in every few seconds—a visual strategy still in place in the latest versions of the Tumblr site. “Turns out that when you make it easy to create interesting things,” reads the About page, “that’s exactly what people do” [

74].

The stress on expressive freedom—on

creative authenticity—was echoed in the app-store listings of Instagram, though with a dash of nostalgia mixed in. The photo-sharing app, started in 2010, initially described itself as a “fast, beautiful and fun way to share your life with friends through a series of pictures” [

75]. The retro logo and Polaroid-esque filters—over-saturated, edge-blurred, and/or simulated graininess—gave off an aura of nostalgic weightiness. The sense of the authentic produced by faux-vintage filtering, as Jurgenson observed [

76], draws on the implicit contrast between the timeworn honesty of the past with a plastic hucksterism of the present. Purchased by Facebook for a reported $1 billion in 2012, the app continued to promote its nostalgic iteration of the creativity pitch: Instagram’s homepage, up until 2013, prominently featured a paperclipped stack of washed out or overexposed photographs, conspicuously analog down to the print-to-black borders. The same year, the company announced its 15-second video feature with a montage of spliced-together footage from users. Set to a twee track of mandolin, a series of one- or two-second shots appear: a desaturated boy leaping into an ocean wave, twenty-somethings goofing around on a city sidewalk through simulated film grain, a pug posed with a fedora and pipe on a lustrous hardwood floor, the requisite espresso pour from above. The effect is a minute-and-a-half pastiche of vaguely retro meaning and memory [

77].

If Tumblr presents itself as a showcase for creative expression, Instagram’s promise of authenticity is through filtered enhancement. The artistic patina encouraged by the app’s marketing bleeds into living itself: The Instagrammer is encouraged to creatively document a life lived well. The proliferation of #nofilter hashtags, and all the published backlash to staged perfection, are expressions of Instagram’s defining paradox: The filtered effort required to achieve the look of throwback authenticity is at the same time disqualifying. Other apps, notably Snapchat, moved to exploit the contradiction—leading, arguably, to Instagram’s recent mimicry of Snapchat features (including the option to message expiring content).

5.4. Spontaneous Authenticity

Snapchat, a Los Angeles-based startup, launched its mobile-phone app in 2011. Pitched as a photo-messaging service, the app’s distinguishing conceit was its ephemeral design: Pictures quickly disappeared once viewed. Snapchat described itself as “real-time picture chatting,” free from the self-presentational anxiety induced by Facebook and other “permanent” social media [

78]. The app, in short, promised a kind of

spontaneous authenticity—a fleeting, low-stakes exchange without reputational consequences.

From the beginning, the company defined itself against its rivals. On its one-year anniversary, for example, Snapchat issued an explicit rebuke to established sites’ museum-like curation: The app is “not all about fancy vacations, sushi dinners, or beautiful sunsets.” This thinly veiled call-out to Facebook and Instagram’s success-theater standards sets up the contrast. Snapchat is for “sharing authentic moments with friends…an inside joke, a silly face, or greetings from a pet fish.” In place of consistency, Snapchat substituted in-the-moment candor [

79].

In a 2012 blog post recounting the young company’s origins, Snapchat’s CEO and co-founder Evan Spiegel reinforced the point. “Snapchat,” he wrote, “isn’t about capturing the traditional Kodak moment.” The app’s core is “communicating with the full range of human emotion…We’re building a photo app that doesn’t conform to unrealistic notions of beauty or perfection” [

80]. The reference to staged flawlessness—and the contrast to “funny, honest” expression—is aimed at Snapchat’s rivals to the north.

In 2014, Spiegel delivered the authenticity claim in strikingly philosophical language, in a keynote address at an industry conference—which was also posted to the Snapchat blog. He defined the “traditional social media view of identity” as “you are the sum of your published experience.” In other words, he added, “pics or it didn’t happen. Or in the case of Instagram: beautiful pics or it didn’t happen AND you’re not cool.” That’s not Snapchat’s view, he continued: “We are who we are today, right now” [

81].

The selfie, Spiegel continued, “marks the transition between digital media as self-expression and digital media as communication.” The key is Snapchat’s ephemerality:

Snapchat discards content to focus on the feeling that content brings to you, not the way that content looks. This is a conservative idea, the natural response to radical transparency that restores integrity and context to conversation. Snapchat sets expectations around conversation that mirror the expectations we have when we’re talking in-person. That’s what Snapchat is all about. Talking through content not around it. With friends, not strangers. Identity tied to now, today. Room for growth, emotional risk, expression, mistakes, room for YOU.

Spiegel’s promise here is immediacy, in the sense of removing the medium, the in-between. Facebook and other “traditional” social media separate offline experience from sharing online: There’s a gap in time and in action, hence the strategic self-fashioning. With Snapchat, the on-and offline intermingle in real time. “We no longer have to capture the ‘real world’ and recreate it online—we simply live and communicate at the same time.”

Observers (e.g., [

82]) pointed to the resemblance of Spiegel’s rhetoric to the arguments of Nathan Jurgenson, a social media scholar who joined the startup as a researcher in 2013. In a post to the company’s official blog, Jurgenson drew an eloquent contrast between “temporary” social media like Snapchat and “permanent” services like Facebook [

83]. In place of the sham authenticity afforded by traditional sites, Jurgenson put forward a spontaneous alternative—what he called the “liquid self.” The “logic of the profile” is “constraining,” a “highly structured set of boxes to squeeze oneself into.” Life as it is actually experienced, in an “ephemeral flow,” is—on Facebook and other permanent sites—”hacked into a collection of separate, discrete, objects to be shoved into the profile containers...captured, preserved, and put behind glass.” Jurgenson traced the static profile logic to the cultural demand for authenticity. If “you cringed at reading the word ‘authentic’ any bit as much as I did typing it,” he wrote, “then you already know that advice can leave little room for anything other than having just one self.” Today’s “dominant social media is too often premised,” he added, “on the idea (and ideal) of having one, true, unchanging, stable self”—and misses the “reality” that humans are “fluid, changing and messy.” Without using the language of authenticity, Jurgenson was of course substituting a rival notion, one that celebrates (in line with Snapchat) spontaneity, “something more fluid, changing, and alive” [

83]. In place of real-name consistency, the app’s claim is that being yourself means in-the-moment flux.

5.5. Anonymous Authenticity

If Snapchat’s answer to the burden of profile upkeep was evanescence, a new crop of social-media apps—Whisper, Secret, and Yik Yak the most prominent—turned to an alternative, nameless form of unburdening. For these apps, the route to authenticity was a kind of identity disguise, on the theory that reputation is the enemy of candor. Facebook emerged from a college directory; the point of these anonymous rivals was, in a sense, to restore the free-wheeling identity play of the 1990s internet (in MUDs, for example). The pitch for anonymous authenticity was a deliberate inversion of Facebook’s real-name, single-identity model. And meticulously manicured self-fashioning was their explicit target.

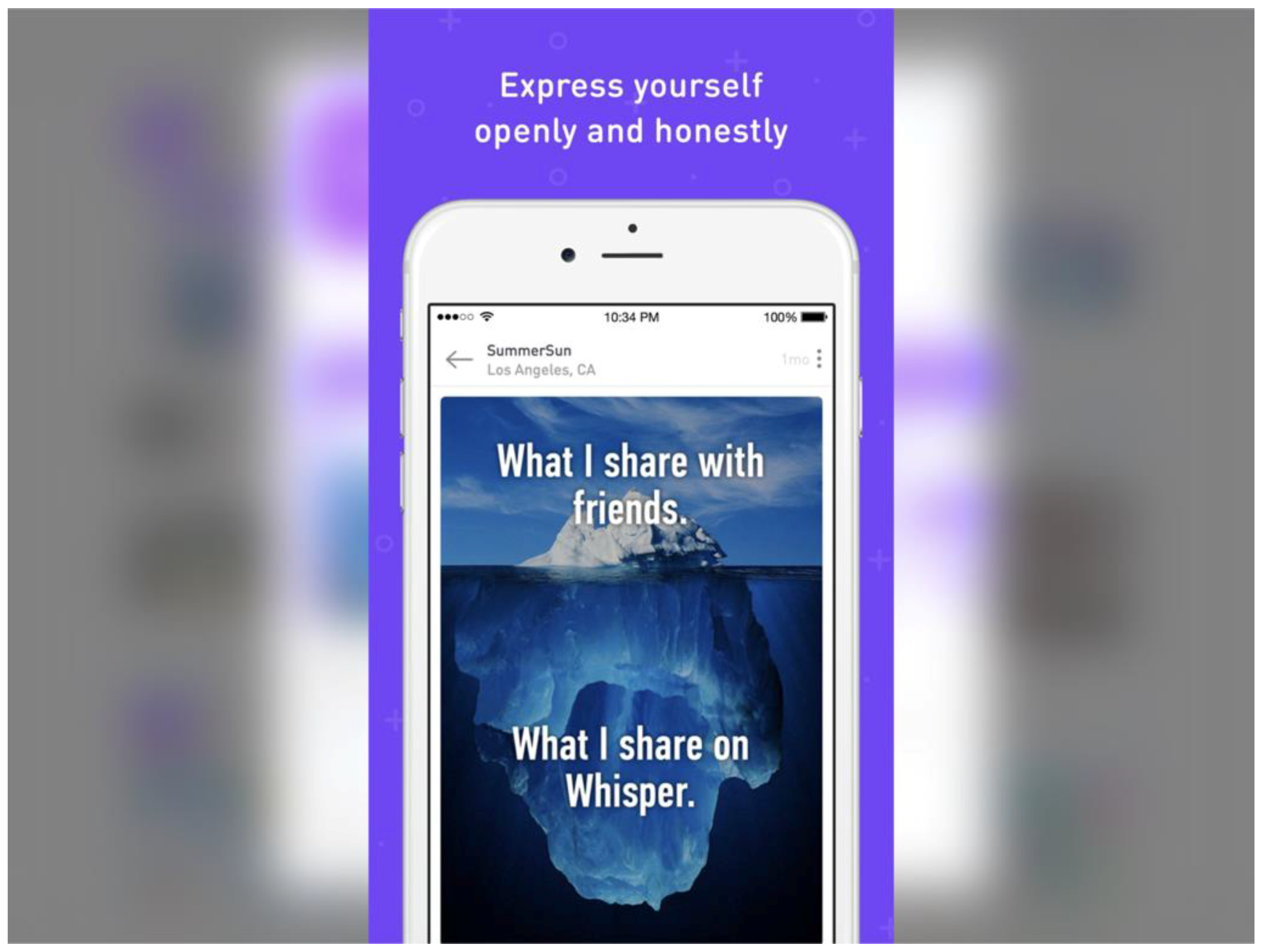

Whisper, launched in 2012, enables users to share meme-like photo/text collages with the rest of its cloaked community. The app’s promotional materials make the case, repeatedly, that the payoff is unfiltered honesty. “Express yourself openly and honestly,” stated the banner on its first App Store screenshot, accompanied by a sample “whisper”: an iceberg photo with “What I share with friends” floating over its tip, and “What I share on Whisper” superimposed on the much larger, submerged remainder (see

Figure 4). “Ever wondered what the people around you are really thinking?” the app’s description teases. Whisper is “an online community where millions of people around the world share real thoughts, trade advice, and get the inside scoop” [

84]. The appeal is that Whisper removes the gauzy social filter that sanitizes other kinds of sharing, whether offline or on Facebook.

A 2014 promotional video hammered home the same themes: “ANONYMITY UNLOCKS AUTHENTICITY,” proclaimed an online banner, as a voiceover spelled out the contrast to real-name competitors: “Whisper is totally anonymous, so you can share what you want without worrying about what your connections or followers or friends might think.” The app has “reimagined social networking” so that you can “BE YOURSELF” [

85]. Whisper, in other words, relieves its users of Facebook’s reputational freight, liberating them to express and emote with carefree gusto.

Yik Yak, the geo-fenced college gossip app started in 2013, has taken a similar tack. Its early home-page designs highlighted the service’s typical blend of observational irreverence and anonymity. Yaks like “S/O to the girl currently puking in the Cook Out parking lot” or “I tried to facetime campus police last night” appeared on a colorful grid [

86]. In an early blog post, the app defended its anonymous design. The “power of anonymity” is that it “gives people a blank slate to work from, effectively removing all preconceptions,” the post read. “The only thing you are judged on is the content that you created, nothing else” [

87]. The argument is that the reputational baggage weighing down social exchanges on other sites, as well as offline, is, thanks to anonymity, eliminated.

By 2016 Yik Yak (“Shipped from Tibet”) adopted a new home-page descriptor: “a feed of all the casual, relatable, heartfelt, and silly things that connect people with their community” [

88]. Even as the venture-funded startup has begun to embrace user handles (with no real-name requirement), the site continues to tout the virtues of freedom from reputation. “Yik Yak,” the app’s blog stated in the March 2016 handles announcement, “is all about building location-based communities to make the world feel small again—and this means helping you develop real, authentic connections with the people around you.” Handles are a “new way for you” to “establish your unique voice” [

89]. In the App Store update announcing the change, Yik Yak encouraged users to create “your unique handle and show off your personality!”:

Be the weather guy, a sports fanatic, SarahSays, that guy, or whatever best expresses who you are. Actually no, don’t be that guy. But be you and get to know the personalities around you.

Yik Yak’s impish embrace of the “heartfelt” and silly, and its language of authentic self-expression, all derive from its liberating, “local banter” anonymity.

Secret, the now-shuttered 2014 Silicon Valley startup, echoed the authenticity rhetoric of Whisper and Yik Yak. “Be yourself,” the app’s homepage urged. “Speak freely, share anything.” Beneath a glyph of a Venetian mask, a banner proclaimed, “No names or profiles.” In a clear reference to Facebook and other real-name services, the promotional copy continued, “It’s not about who you are—it’s about what you say. It’s not about bragging—it’s about sharing, free of judgment” [

91]. The contrast to the highlight-reel curation of name-tethered services like Instagram is predicated on honesty: No need for filtered embellishments here.

5.6. Segregated Authenticity

When Larry Page, Google’s co-founder, took the CEO helm in 2011, he positioned the search giant’s new social-media service, Google+, as an existential answer to cross-town rival Facebook. The distinguishing feature of Google’s alternative was the ability to sort friends into “Circles,” relevant groupings meant to map onto a user’s complex social life. The heavily promoted idea was that Google+’s Circles mimic the kind of audience-specific sharing we all engage in offline. Here again was a claim for genuine self-expression: Google+ frees users from the lowest-common-denominator, one-size-fits-all self that they are compelled to perform on Facebook.

Circles, which permits selective sharing to user-assigned groups, dominated Google’s marketing rollout for the service. A 2011 animated video titled “Sharing but like real life,” began with the everywomen narrator observing, “I have a lot of different people in my life”: her friends, family, co-workers and “biking buddies,” to “name a few.” She has “lots to share,” she said, but doesn’t want to “share everything with everyone”—an implicit dig at Facebook’s one-big-audience model (though group-specific sharing was already possible, if less prominent, on Facebook by the time Google+ launched). “What if,” the narrator continued, “online sharing worked more like your real-life relationships, where you choose who gets to know what?” Circles lets her share party photos with her college friends, and so on. “So bust out those dance moves and Ruth doesn’t need to know,” she concluded [

92].

The appeal here is to “real-life”

segregated authenticity: Face-to-face, we all present different aspects of ourselves according to who we are speaking with. This tailored form of interaction—what Erving Goffman called “audience segregation” ([

93], p. 49)—is Google’s alternative to the airbrushed sharing on Facebook.

The earliest Google+ homepage issued a similar appeal. The Circles feature dominated the page with a centered photo and a brief pitch: “An easy way to share some things with college buddies, others with your parents, and almost nothing with your boss. Just like in real life” [

94]. The claim is that Google+ mimics a key facet of offline “real life”: People only reveal their “genuine” selves to intimates, when they can drop the performances and concealments required by social etiquette.

Even as Google’s answer to Facebook failed to gain user traction, the company continued to tout Circles as the service’s key differentiator. Two years into the venture, the site’s homepage was bannered, “With Google+, you can share the right things with the right people” [

95]. In a 2013 feature tour, Google encouraged users to “Show the world who you are and what you’re passionate about” and to “Be yourself all across Google” [

52]. It was only in 2016—as the company conceded defeat by unbundling Hangouts and the Photos services from Google+—that the social network shifted its appeal to would-be users. A new grid of colorful cards greets visitors to the Google+ homepage, “Featured Collections” of topical, curated feeds: “Follow amazing stuff created by passionate people,” the site now urges [

96]. But for most of its ill-fated campaign against Facebook, the service appealed to authenticity: Here is a social network, the promise was, that lets you drop the social mask you don when posting to rival apps.

5.7. Anti-Commercial Authenticity

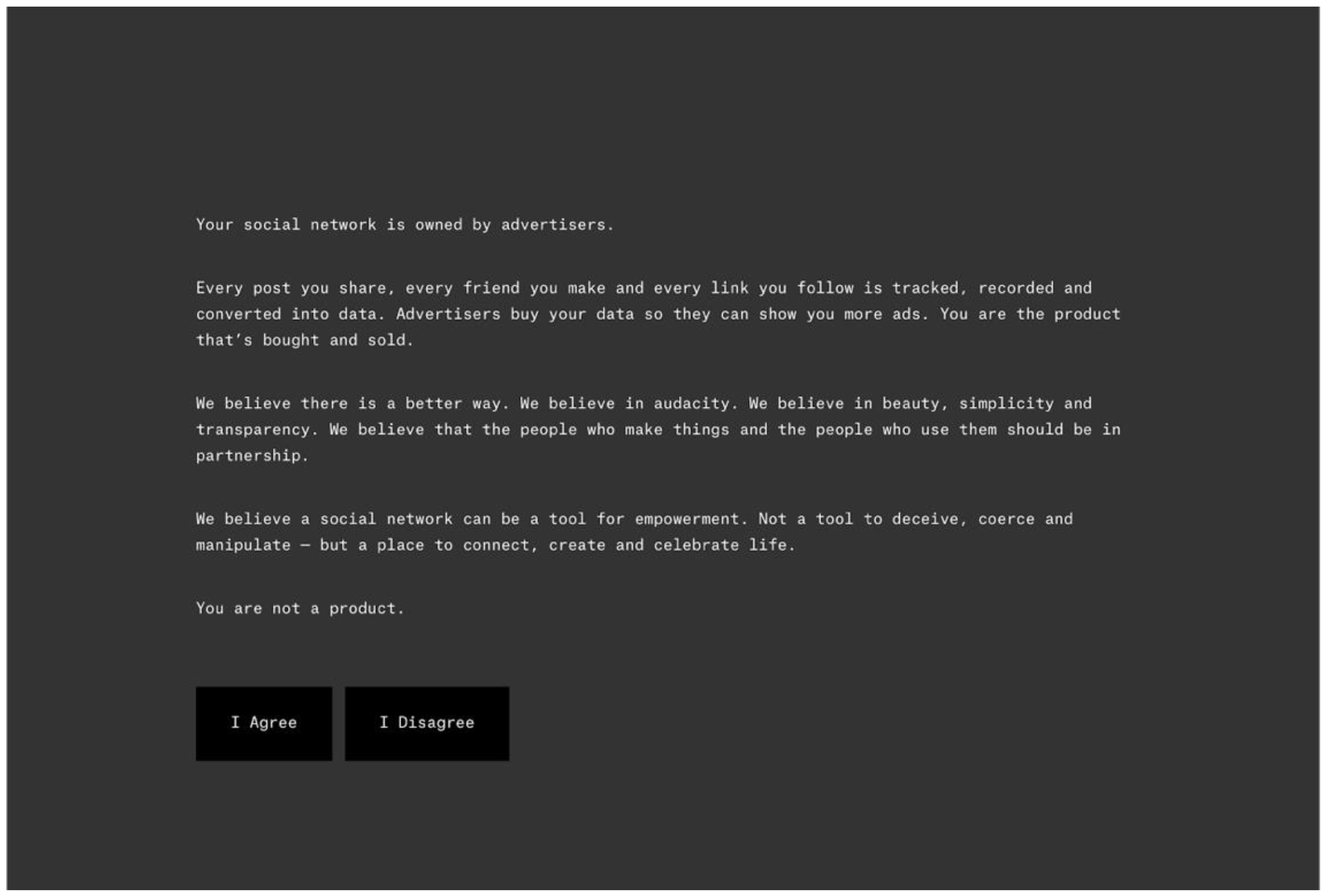

Ello took a different tack, defining itself as an ad-free anti-Facebook. The site, launched in 2014, carried an austere, colorless aesthetic, with a typewriter font reminiscent of a 1960s protest rag. And, indeed, Ello’s homepage featured a defiant “Manifesto,” centered on an indictment of Facebook’s data-driven business model (see

Figure 5). “Your social network is owned by advertisers,” read the manifesto:

Every post you share, every friend you make and every link you follow is tracked, recorded and converted into data. Advertisers buy your data so they can show you more ads. You are the product that’s bought and sold.

The site was calling out Facebook for its audience-labor exploitation, in the language and typeface of leftist dissent. Facebook and most other social media, of course, bundle user profiles and attention to sell to advertisers, who pay a premium to serve targeted ads back to the user. Ello’s critique, frequently issued by academics (e.g., [

98]), is startling for its direct appeal to justice. “We believe,” the manifesto continued, “in a better way.” A social network should not be a “tool to deceive, coerce and manipulate—but a place to connect, create and celebrate life” [

97].

The manifesto’s final, stark line was set as its own paragraph: “You are not a product.” Two square buttons, “I Agree” and “I Disagree,” appeared below. Click the “Agree” button, and you were delivered to Ello’s sign-up page. The “Disagree” button, in a flash of dark humor, took users to the professed enemy, Facebook. Ello’s was a full-throttled appeal to

anti-commercial authenticity [

97].

The site garnered a burst of media attention in late 2014 after Facebook suspended the accounts of San Francisco drag queens over real-name violations [

99]. The next year, after interest in the site waned, Ello pivoted—to borrow the Silicon Valley verb—to a creative/maker identity not unlike Tumblr’s. The typewriter font and ascetic gray were dropped for a full-screen banner featuring vivid user photos on rotation, overlain with the motto, “We are creators.” On its app store listing, the company calls itself “The Creators Network”. Despite the new accent on creativity, Ello continues to draw an anti-commercial contrast with Facebook. “Ello is a place where passion triumphs over conformity, and success is measured in ideas shared, not ads shared,” reads the copy. “No ads. No manipulative algorithms. You control what you see” [

100].

6. Emerging Social Networks

To investigate our hunch that new social networks would, like their predecessors, market themselves as redoubts of authenticity, we turned to three recently launched services, Plag, Beme, and Peach.

Plag, an information-sharing network started in Lithuania, promotes its service with a 90-second black-and-white animated slideshow on its homepage. The tone, like Ello’s circa 2014, is censorious and manifesto-like. “YOUR OPINION IS WORTH NOTHING,” proclaims the opening slide. Referring to media and corporate “gatekeepers,” the video adds in another slide, “Social networks seemed to be the solution,

but they failed.” What if, the next-to-last slide asked, “there was a better way?” Something, the final slide suggested, “that can

bring our voices back.” Beneath a “TELL ME” button—which links to a sign-up page—the video includes a hyperlinked sentence: “Oh, stop it, the world is perfect already.” The link’s referent? Facebook [

101].

Meanwhile, the tagline for Beme, launched in 2015 by the filmmaker Casey Neistat and recently acquired by CNN, is “Share video. Honestly.” Beme’s app store description unabashedly claims the authenticity mantle. The app, the copy reads, is the “simplest and most authentic way to share your personal experience.” Instantly capture “real moments,” see how friends “honestly live their lives,” and “send them genuine reactions as you watch along” [

102].

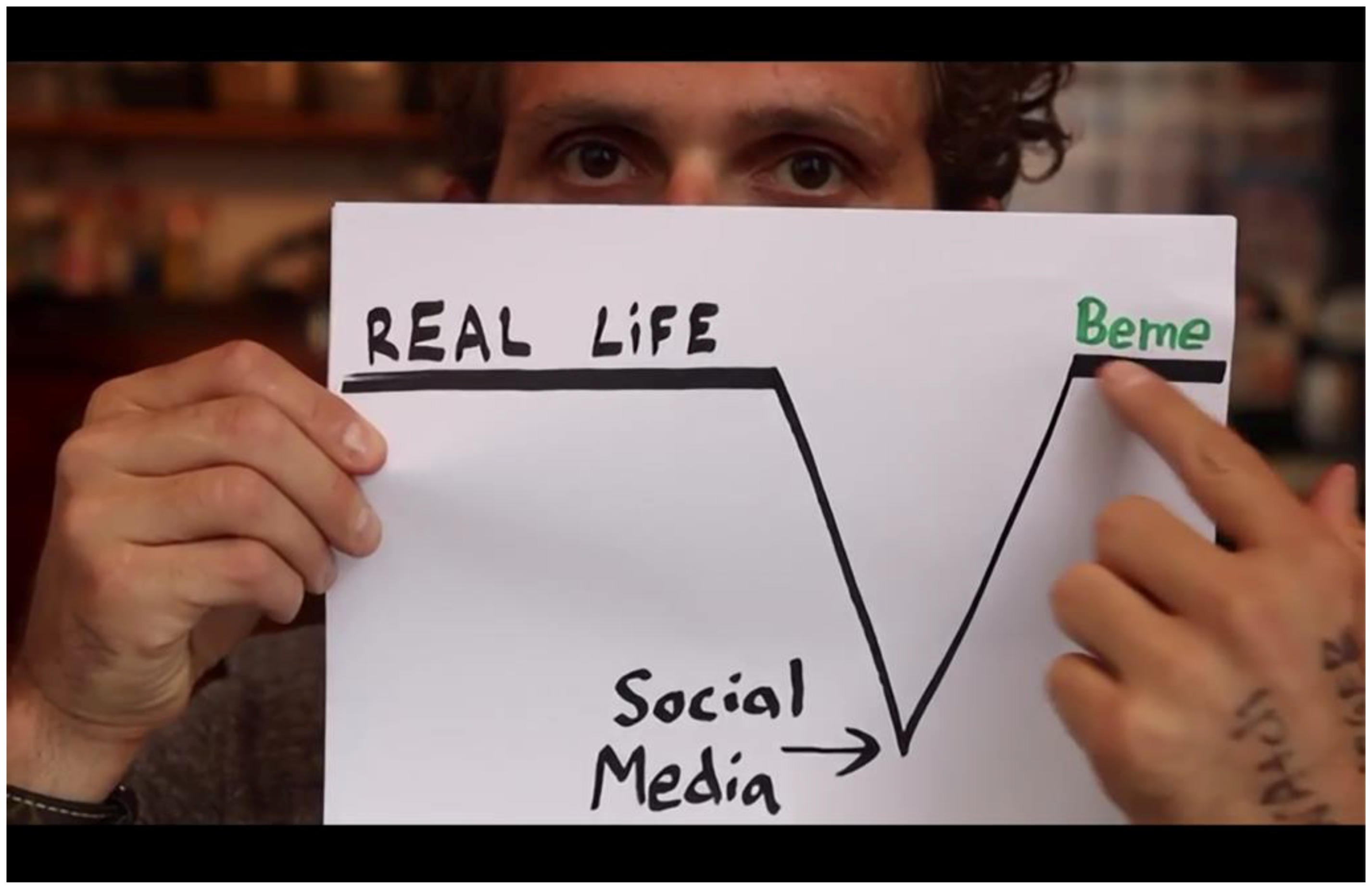

The service’s website is an austere all-black, with a one-letter logo and a tiny, typewriter-fonted line of text. The site’s only content—its sole page—is a centered, captionless YouTube video featuring Neistat in a gray t-shirt. The setting is a tool-littered garage, with the camera tight around Neistat’s lined face. “Social media, it’s supposed to be a digital or virtual version of who we are as people,” says Neistat. “Instead it’s this highly sculpted, calculated, calibrated version of who we are.” Beme’s “new version of social” cuts away the airbrushed performance; the app records its video-snippet “bemes,” Neistat explains, when a user places a phone on his chest or some other object. The recording ends when the phone is moved, and is then instantly uploaded to the app. “That’s it. There’s no preview, there’s no review, and there’s never a need to look at your phone.” Beme bypasses the obsessive self-primping of other apps, Neistat explains with a hand-held sheet of white construction paper featuring a simple line graph. A felt-tip markered “REAL LIFE” appears high on the page, with the line plunging to a skewed-angle “Social Media” label—followed by a sharp ascent to a green-lettered “Beme” [

103] (see

Figure 6). With Beme, real-time experience isn’t sacrificed to record-and-share self-absorption. Users can stare at the sunset—or keep watching the rock concert—and still share the experience. “There’s no staring at your phone.”

The app, and Neistat, even take aim at the standardized likes-and-hearts feedback common to the other platforms. On Beme the thumbs-up and hearts are replaced by “real-time selfies”—screen-tap generated reaction shots sent straight to fellow users. And like Snapchat circa 2012—and touted with near-identical language—bemes disappear after a single view. The app unburdens users from the twin evils of persistence and shareability, and restores the real-time spontaneity of face-to-face conversation. As Neistat bites into an apple, he wraps up the pitch: Beme “removes the self-awareness and the self-consciousness from sharing on social media” [

103].

The video’s low-fi amateurism, its YouTube aesthetic, is intentional, of course—an argument-in-form for the app’s performance-slaying design. The plain irony is that Neistat—a professional filmmaker—is here engaged in the same kind of managed “authenticity” for which he calls out the legacy apps. And Beme’s stripped-down feature set does not remove the self-conscious decision to share. Users are still performing to a camera at self-selected intervals, even (and especially) if they adapt to the app’s stylized #nofilter aesthetic. No one doubts the strategic image-management behind a Facebook status or Instagram. Beme (and Snapchat too) bank on apparent spontaneity, on what Goffman called “calculated unintentionality” ([

93], p. 20). It’s not

self-awareness that’s removed, but instead

others’ awareness of the Bemer’s self-conscious staging. In that respect the app remains caught up in the “highly sculpted, calculated, calibrated” performance economy pioneered by its competitors [

103].

In early 2016 another hyped app hit the market, Peach, with a similar marketing conceit. The service’s flat icon and monochromatic website leads with a single, sans serif line: “Peach is a fun, simple way to keep up with friends and be yourself” [

104]. The app’s minimalism is woven into its design: Its “little updates” are a series of shortcodes (“magic words”)—type the phrase “gif” and Giphy-powered search window appears. Type “throwback” and the app will retrieve a random photo from your archive. Like most other social media apps, Peach is filled with slangy, conversational tips (“assemble your squad,” “cool, right?”), punctuated by emoji: “Your space is looking great. 💕”. Social media staples like friends, likes and comments are built into Peach, and the service even revived the Facebook poke (a “boop” in Peach lingo) [

105].

The emoji-laden brevity is at the app’s core. If Beme’s rendering of authenticity was all about removing the filter, Peach’s take is about enabling

emotion. Users are encouraged to wave, hiss, or send cake to their friends; the service’s “magic words” cluster around what might be called affective sharing. Tap in “mood” for example, and you select from a carousel of in-the-moment emotional states (“😭 jealous”). The word “song” will trigger the app to “listen” to what’s playing on your iPhone, so you can share that faithful emotional barometer too. As Navneet Alang recently observed, Peach has a “ruthless focus on affect”: “Its emphasis on eliciting images, mood, and creative sparks in miniature seems uniquely aimed at the heart rather than the head” [

106]. This is another way of saying that the app is making an authenticity appeal, in an emotional key. Authenticity, from its 18th-century Romantic roots onward, has elevated sentiment, raw and passion-filled, over plodding logic—the “spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings,” in Wordsworth’s phrase.

7. Conclusions

Facebook, for all the battering the service (and company) takes from its competitors, remains unquestionably dominant. According to Facebook, the site has 1.71 billion monthly users—a year-over-year jump of 15 percent. With the notable exception of Snapchat, which is growing at a faster clip, Facebook has fended off its rivals and sidestepped the Friendster/MySpace death spiral. One explanation is scale: The site’s ubiquity means that abstention is an act of social deviance. Alternative services, of course, are hobbled by a comparative network disadvantage: The emotional resonance of Peach’s Magic Words cannot register if no one else is there to receive them. Facebook’s canny acquisition of future rivals—Instagram included—and its nimble engineering culture prevent startups from gaining market purchase. Aggressively promoted feature roll-outs, like Facebook Live, are the software equivalent of obliteration by incorporation, as rivals’ affordances get coded into the Menlo Park juggernaut’s feature set.

Does Facebook’s durability mean that its real-name authenticity pitch is convincing? If most of its competitors fail to win lasting defections, are their competing brands of authenticity (and their critiques of Facebook’s nominal sort) unappealing? Is Facebook’s success an implicit referendum on Zuckerberg’s persistent, single-identity ideal?

In our view, Facebook’s staying power owes much more to network lock-in and clever engineering than it does to users’ endorsement of real-name consistency as a moral standard. The undeniably performative dimension of the site’s core feature set—fueled by mutual awareness of time lags, editing control, and context collapse—means that its self-description as a platform for authentic expression is always and already suspect. The many-angled offensive mounted by all the aspiring Facebook slayers—the ongoing contest for authenticity that we document in this article—is sustained by its contradictions. The evidence of, indeed the unending search for, the inauthentic on Facebook is exactly the space opened up for competitors’ differently grounded authenticity claims.

Of course Facebook has reasons (356 billion of them [

107]) to defend its real-name mandate. The foundation of the platform’s advertising supremacy is its granular, name-linked targeting, for which advertisers willingly pay a premium. The company’s data-supplement strategy—buying up personal data from third-party brokerages to blend with its own profiles [

108]—depends on the stable, trackable referent of legal identity. To the extent that Facebook—through acquisition, feature accretion, and even the nominal authenticity appeal itself—maintains its dominance, self-expression on social media will continue to feed the “big data divide” [

109]. With the same shares and comments a user post to their friends, Facebook generates its own, lucrative self-likeness. One irony is that seeing this digital doppelgänger served back in ads may itself undercut the company’s authenticity appeal.

With these and other Facebook contradictions in mind, we expect the cycle to remain in motion. New and existing networks will continue to define themselves against their rivals by invoking some notion of the authentic, for as long as the ideal itself maintains its powerful hold. Since the modern conditions that gave rise to authenticity—above all, the pervasive experience of instrumentality in everyday life—are likely to persist or even intensify, the ideal has a long shelf-life. And since the authentic is always susceptible to strategic redeployment, reactive novelty is an endemic trait. What this means is that next year’s Beme—whatever it is—will probably come wrapped in the cloak of authenticity.