Family Networks and Psychological Well-Being in Midlife

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Family Networks and Psychological Well-Being

1.1.1. Gender within the Context of Family Networks

1.1.2. Other Factors Affecting Psychological Well-Being

2. Data and Methods

2.1. Procedures

2.2. Measures

2.3. Plan of Analysis

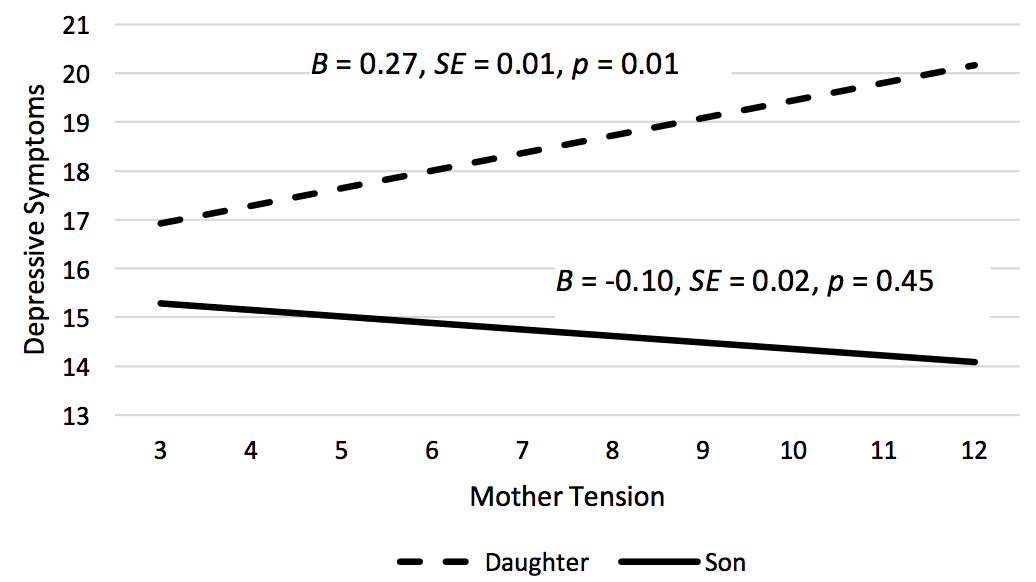

3. Results

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Allison, Paul D. 2010. Missing Data. In Handbook of Survey Research. Edited by James D. Wright and Peter V. Marsden. Bingley: Emerald, pp. 631–58. [Google Scholar]

- Amato, Paul R., and Tamara D. Afifi. 2006. Feeling Caught between Parents: Adult Children’s Relations with Parents and Subjective Well-being. Journal of Marriage and Family 68: 222–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonucci, Toni C., Hiroko Akiyama, and Alicia Merline. 2001. Dynamics of Social Relationships in Midlife. In Handbook of Midlife Development. Edited by Margie E. Lachman. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons Inc., pp. 571–98. [Google Scholar]

- Antonucci, Toni C., Hiroko Akiyama, and Keiko Takahashi. 2004. Attachment and Close Relationships across the Life Span. Attachment & Human Development 6: 353–70. [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Kalifa, Eran, and Eshkol Rafaeli. 2013. Disappointment’s Sting is Greater than Help’s Balm: Quasi-signal Detection of Daily Support Matching. Journal of Family Psychology 27: 956–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bedford, Victoria H., and Paula S. Avioli. 2012. Siblings in Middle and Late Adulthood. In Handbook of Families and Aging, 2nd ed. Edited by Rosemary Blieszner and Victoria H. Bedford. Santa Barbara: Praegar, pp. 125–53. [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard-Fields, Fredda, Renee Stein, and Tonya L. Watson. 2004. Age Differences in Emotion-Regulation Strategies in Handling Everyday Problems. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences 59: 261–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, Lori D., Ingrid A. Connidis, and Lorraine Davies. 1999. Sibling Ties in Later Life: A Social Network Analysis. Journal of Family Issues 20: 114–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, Deborah, and Kristen W. Springer. 2010. Advances in Families and Health Research in the 21st Century. Journal of Marriage and Family 72: 743–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, Deborah, Vicki A. Freedman, Jennifer C. Cornman, and Norbert Schwarz. 2014. Happy Marriage, Happy Life? Marital Quality and Subjective Well-being in Later Life. Journal of Marriage and Family 76: 930–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carstensen, Laura. 1992. Social and emotional patterns in adulthood: Support socioemotional selectivity theory. Psychology and Aging 7: 331–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charles, Susan Turk, and Laura L. Carstensen. 2007. Emotion Regulation and Aging. In Handbook of Emotion Regulation. Edited by James J. Gross. New York: Guilford Press, pp. 307–27. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Sheung-Tak, Kin-Kit Li, Edward M. F. Leung, and Alfred C. M. Chan. 2011. Social Exchanges and Subjective Well-being: Do Sources of Positive and Negative Exchanges Matter? Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences 66: 708–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chodorow, Nancy J. 1989. Feminism and Psychoanalytic Theory. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, Heejeong, and Nadine F. Marks. 2008. Marital Conflict, Depressive Symptoms, and Functional Impairment. Journal of Marriage and Family 70: 377–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cicirelli, Victor G. 1989. Feelings of Attachment to Siblings and Well-being in Later Life. Psychology and Aging 4: 211–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarke, Philippa, Victor Marshall, James House, and Paula Lantz. 2011. The Social Structuring of Mental Health over the Adult Life Course: Advancing Theory in the Sociology of Aging. Social Forces 89: 1287–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Sheldon. 2004. Social Relationships and Health. American Psychologist 59: 676–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connidis, Ingrid A., and Lori D. Campbell. 1995. Closeness, Confiding, and Contact among Siblings in Middle and Late Adulthood. Journal of Family Issues 16: 722–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutrona, Carolyn E. 1996. Social Support in Couples: Marriage as a Resource in Times of Stress. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, vol. 13. [Google Scholar]

- DeLongis, Anita, Martha Capreol, Susan Holtzman, Tess O’Brien, and Jennifer Campbell. 2004. Social Support and Social Strain among Husbands and Wives: A Multilevel Analysis. Journal of Family Psychology 18: 470–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dixon, John, and Clyde Tucker. 2010. Survey Nonresponse. In Handbook of Survey Research. Edited by Peter. V. Marsden and James D. Wright. Bingley: Emerald Group, pp. 593–63. [Google Scholar]

- Fingerman, Karen L., ed. 2001. Aging Mothers and Their Adult Daughters: A Study in Mixed Emotions. New York: Springer Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Fingerman, Karen L., and Elizabeth L. Hay. 2002. Searching Under the Streetlight? Age Biases in the Personal and Family Relationships Literature. Personal Relationships 9: 415–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fingerman, Karen L., Elizabeth L. Hay, and Kira S. Birditt. 2004. The Best of Ties, the Worst of Ties: Close, Problematic, and Ambivalent Social Relationships. Journal of Marriage and Family 66: 792–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fingerman, Karen L., Lindsay Pitzer, Eva S. Lefkowitz, Kira S. Birditt, and Daniel Mroczek. 2008. Ambivalent Relationship Qualities between Adults and Their Parents: Implications for the Well-being of Both Parties. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences 63: 362–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiori, Katherine L., and Nathan S. Consedine. 2013. Positive and Negative Social Exchanges and Mental Health across the Transition to College Loneliness as a Mediator. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 30: 920–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilligan, Carol. 1982. In a Different Voice: Psychological Theory and Women’s Development. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gilligan, Megan, J. Jill Suitor, Seoyoun Kim, and Karl Pillemer. 2013. Differential Effects of Perceptions of Mothers’ and Fathers’ Favoritism on Sibling Tension in Adulthood. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences 68: 593–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilligan, Megan, J. Jill Suitor, Scott Feld, and Karl Pillemer. 2015. Do Positive Feelings Hurt? Disaggregating Positive and Negative Components of Intergenerational Ambivalence. Journal of Marriage and Family 77: 261–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ha, Jung-Hwa. 2010. The Effects of Positive and Negative Support from Children on Widowed Older Adults’ Psychological Adjustment: A Longitudinal Analysis. The Gerontologist 50: 471–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahn, Robert L., and Toni C. Antonucci. 1980. Convoys over the Life Course: Attachment, Roles, and Social Support. In Life-Span Development and Behavior. Edited by Paul B. Baltes and Orville G. Brim Jr. New York: Academic Press, vol. 3, pp. 254–83. [Google Scholar]

- Kalmijn, Matthijs, and Aart C. Liefbroer. 2011. Nonresponse of Secondary Respondents in Multi-actor Surveys: Determinants, Consequences, and Possible Remedies. Journal of Family Issues 32: 735–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kamp Dush, Claire M., Miles G. Taylor, and Rhiannon A. Kroeger. 2008. Marital Happiness and Psychological Well-being across the Life Course. Family Relations 57: 211–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Hyoun K., and Patrick C. McKenry. 2002. The Relationship between Marriage and Psychological Well-being: A Longitudinal Analysis. Journal of Family Issues 23: 885–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, N., and Christopher G. Ellison. 2007. Parental Religious Socialization Practices and Self-Esteem in Later Life. Review of Religious Research 49: 109–27. [Google Scholar]

- Lackner, Jeffrey M., Gregory D. Gudleski, Rebecca Firth, Laurie Keefer, Darren M. Brenner, Katie Guy, Camille Simonetti, Christopher Radziwon, Sarah Quinton, Susan S. Krasner, and et al. 2013. Negative Aspects of Close Relationships Are More Strongly Associated than Supportive Personal Relationships with Illness Burden of Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 74: 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LaSala, Michael C. 2002. Walls and Bridges: How Coupled Gay Men and Lesbians Manage their Intergenerational Relationships. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy 28: 327–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Hyo Jung, and Maximiliane E. Szinovacz. 2016. Positive, Negative, and Ambivalent Interactions with Family and Friends: Associations with Well-being. Journal of Marriage and Family 78: 660–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavandadi, Shahrzad, Dara H. Sorkin, Karen S. Rook, and Jason T. Newsom. 2007. Pain, Positive and Negative Social Exchanges, and Depressive Symptomatology in Later Life. Journal of Aging and Health 19: 813–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCall, George J., and Jerry Laird Simmons. 1966. The Role-identity Model. In Identities and Interactions. New York: Free Press, pp. 63–104. [Google Scholar]

- Nevill, Dorothy D., and Donald E. Super. 1986. The Salience Inventory: Theory, Application, and Research: Manual, Research ed. Palo Alto: Consulting Psychologists Press. [Google Scholar]

- Newsom, Jason T., Masami Nishishiba, David L. Morgan, and Karen S. Rook. 2003. The Relative Importance of Three Domains of Positive and Negative Social Exchanges: A Longitudinal Model with Comparable Measures. Psychology and Aging 18: 746–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul, Elizabeth L. 1997. A Longitudinal Analysis of Midlife Interpersonal Relationships and Well-being. In Multiple Paths of Midlife Development. Edited by Margie E. Lachman and Jacquelyn B. James. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, pp. 171–206. [Google Scholar]

- Polenick, Courtney A., Nicole DePasquale, David J. Eggebeen, Steven H. Zarit, and Karen L. Fingerman. 2016. Relationship Quality between Older Fathers and Middle-aged Children: Associations with Both Parties’ Subjective Well-Being. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Proulx, Christine M., Heather M. Helms, and Cheryl Buehler. 2007. Marital Quality and Personal Well-being: A Meta-analysis. Journal of Marriage and Family 69: 576–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rook, Karen S. 2001. Emotional Health and Positive versus Negative Social Exchanges: A Daily Diary Analysis. Applied Developmental Science 5: 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, Catherine E., and John Mirowsky. 1988. Child Care and Emotional Adjustment to Wives’ Employment. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 29: 127–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossi, Alice S., and Peter H. Rossi. 1990. Of Human Bonding: Parent-Child Relations Across the Life Course. Piscataway: Transaction Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Schieman, Scott, and Paul Glavin. 2011. Education and Work-Family Conflict: Explanations, Contingencies, and Mental Health Consequences. Social Forces 89: 1341–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sechrist, Jori, J. Jill Suitor, Catherine Riffin, Kadari Taylor-Watson, and Karl Pillemer. 2011. Race and Older Mothers’ Differentiation: A Sequential Quantitative and Qualitative Analysis. Journal of Family Psychology 25: 837–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silverstein, Merril, Roseann Giarrusso, and Vern L. Bengtson. 1998. Intergenerational Solidarity and the Grandparent Role. In Handbook on Grandparenthood. Edited by Maximiliane E. Szinovacz. Westport: Greenwood Publishing Group, pp. 144–58. [Google Scholar]

- Spitze, Glenna, and Katherine Trent. 2006. Gender Differences in Adult Sibling Relations in Two-Child Families. Journal of Marriage and Family 68: 977–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitze, Glenna, and Katherine Trent. 2016. Changes in Individual Sibling Relationships in Response to Life Events. Journal of Family Issues. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suitor, J. Jill, and Karl Pillemer. 2006. Choosing Daughters: Exploring Why Mothers Favor Adult Daughters over Sons. Sociological Perspectives 49: 139–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suitor, J. Jill, Jori Sechrist, Mari Plikuhn, Seth T. Pardo, Megan Gilligan, and Karl Pillemer. 2009. The Role of Perceived Maternal Favoritism in Sibling Relations in Midlife. Journal of Marriage and Family 71: 1026–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suitor, J. Jill, Megan Gilligan, and Karl Pillemer. 2013. Continuity and Change in Mothers’ Favoritism toward Offspring in Adulthood. Journal of Marriage and Family 75: 1229–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suitor, J. Jill, Megan Gilligan, Kaitlin Johnson, and Karl Pillemer. 2014. Caregiving, Perceptions of Maternal Favoritism, and Tension among Siblings. The Gerontologist 5: 580–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suitor, J. Jill, Gulcin Con, Kaitlin Johnson, Siyun Peng, and Megan Gilligan. 2015a. Parent-child Relationships. In Encyclopedia of Adulthood and Aging. Edited by Susan K. Whitbourne. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell, vol. 3, pp. 1011–15. [Google Scholar]

- Suitor, J. Jill, Megan Gilligan, Siyun Peng, Jong Hyun Jung, and Karl Pillemer. 2015b. Role of Perceived Maternal Favoritism and Disfavoritism in in Adult Children’s Psychological Well-Being. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suitor, J. Jill, Megan Gilligan, and Karl Pillemer. 2015c. Stability, Change, and Complexity in Later Life Families. In Handbook of Aging and the Social Sciences, 8th ed. Edited by Linda K. George and Kenneth F. Ferraro. New York: Elsevier/Academic, pp. 206–26. [Google Scholar]

- Suitor, J. Jill, Megan Gilligan, Karl Pillemer, Karen L. Fingerman, Kyungmin Kim, Merril Silverstein, and Vern L. Bengtson. 2017. Applying Within-Family Differences Approaches to Enhance Understanding of the Complexity of Intergenerational Relations. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Super, Donald E. 1990. A Life-Span, Life-Space Approach to Career Development. In Career Choice and Development: Applying Contemporary Theories to Practice. Edited by Duane Brown and Linda Brooks. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, pp. 167–261. [Google Scholar]

- Umberson, Debra. 1992. Relationships between Adult Children and their Parents: Psychological Consequences for Both Generations. Journal of Marriage and the Family 54: 664–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umberson, Debra, and Jennifer Karas Montez. 2010. Social Relationships and Health a Flashpoint for Health Policy. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 51: S54–S66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umberson, Debra, Meichu D. Chen, James S. House, Kristine Hopkins, and Ellen Slaten. 1996. The Effect of Social Relationships on Psychological Well-being: Are Men and Women Really So Different? American Sociological Review 61: 837–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umberson, Debra, Kristi Williams, Daniel A. Powers, Hui Liu, and Belinda Needham. 2006. You Make Me Sick: Marital Quality and Health over the Life Course. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 47: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umberson, Debra, Mieke Beth Thomeer, and Kristi Williams. 2013. Family Status and Mental Health: Recent Advances and Future Directions. In Handbook of the Sociology of Mental Health, 2nd ed. Edited by Carol S. Aneshensel, Jo C. Phelan and Alex Bierman. New York: Springer Publishing, pp. 405–31. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, Russell A. 2008. Multiple Parent-Adult Child Relations and Well-Being in Middle and Later Life. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B 63: S239–S247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, Russell A., Glenna Spitze, and Glenn Deane. 2009. The More the Merrier? Multiple Parent-Adult Child Relations. Journal of Marriage and Family 71: 161–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, Lynn. 2001. Sibling Relationships over the Life Course: A Panel Analysis. Journal of Marriage and Family 63: 555–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, Lynn K., and Agnes Riedmann. 1992. Ties among Adult Siblings. Social Forces 71: 85–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, Kristi. 2003. Has the Future of Marriage Arrived? A Contemporary Examination of Gender, Marriage, and Psychological Well-being. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 44: 470–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics of Respondents | M, SD, % |

|---|---|

| Family Level Characteristics | |

| Family size (M, SD) | 4.21 (1.85) |

| Race | |

| White (%) | 87.7 |

| Adult Child Level Characteristics | |

| Age (M, SD) | 49.1 (5.62) |

| Daughters (%) | 55.4 |

| Parents (%) | 86.9 |

| Employed (%) | 85.7 |

| Subjective Health (M, SD) | 3.93 (0.98) |

| Educational Attainment (%) | |

| Less than high school | 3.4 |

| High school graduate | 14.7 |

| Some college | 17.7 |

| College graduate | 64.1 |

| Measure | Depressive Symptoms | Spouse Tension | Mother Tension | Sibling Tension |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depressive Symptoms | 1.00 | 0.12 * | 0.13 ** | 0.12 * |

| Spouse Tension | 1.00 | 0.10 * | 0.20 ** | |

| Mother Tension | 1.00 | 0.34 ** | ||

| Sibling Tension | 1.00 |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | SE | Estimate | SE | Estimate | SE | |

| Family Size | −0.23 * | 0.10 | −0.21 * | 0.10 | −0.25 ** | 0.10 |

| Age | −0.01 | 0.03 | −0.02 | 0.03 | −0.02 | 0.03 |

| Education | 0.09 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.08 | 0.12 |

| Parent | −1.44 ** | 0.46 | −1.36 ** | 0.46 | −1.35 ** | 0.46 |

| Employed | −1.46 ** | 0.46 | −1.57 *** | 0.46 | −1.43 ** | 0.46 |

| Health | −1.34 *** | 0.17 | −1.32 *** | 0.17 | −1.34 *** | 0.17 |

| Race (White = 1) | 0.69 | 0.53 | 0.88 | 0.54 | 0.75 | 0.53 |

| Daughters | 0.50 | 0.33 | 0.17 | 0.32 | 0.24 | 0.32 |

| Spouse Tension | 0.21 ** | 0.08 | - | - | - | - |

| Mother Tension | - | - | 0.20 ** | 0.08 | - | – |

| Sibling Tension | - | - | - | - | 0.21 ** | 0.08 |

| Constant | 17.28 *** | 2.00 | 17.61 *** | 1.99 | 17.87 *** | 1.96 |

| Model Statistics | ||||||

| −2logL | 2632.31 | 2633.33 | 2633.61 | |||

| AIC | 2656.31 | 2657.33 | 2657.61 | |||

| BIC | 2706.76 | 2707.78 | 2708.07 | |||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | SE | Estimate | SE | |

| Family Size | −0.23 * | 0.10 | −0.25 ** | 0.10 |

| Age | −0.01 | 0.03 | −0.01 | 0.03 |

| Education | 0.08 | 0.12 | 0.09 | 0.12 |

| Parent | −1.46 *** | 0.46 | −1.45 *** | 0.45 |

| Employed | −1.49 *** | 0.46 | −1.63 *** | 0.46 |

| Health | −1.30 *** | 0.17 | −1.27 *** | 0.17 |

| Race (White = 1) | 0.85 | 0.53 | 0.83 | 0.53 |

| Daughters | 0.37 | 0.33 | 0.53 | 1.41 |

| Spouse Tension | 0.17 * | 0.08 | 0.31 ** | 0.11 |

| Mother Tension | 0.14 | 0.08 | −0.10 | 0.13 |

| Sibling Tension | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.19 | 0.14 |

| Daughters X Spouse Tension | −0.25 | 0.15 | ||

| Daughters X Mother Tension | 0.37 * | 0.16 | ||

| Daughters X Sibling Tension | −0.11 | 0.18 | ||

| Constant | 15.88 *** | 2.06 | 15.59 *** | 2.20 |

| Model Statistics | ||||

| −2logL | 2625.34 | 2617.84 | ||

| AIC | 2653.34 | 2651.84 | ||

| BIC | 2712.21 | 2723.31 | ||

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gilligan, M.; Suitor, J.J.; Nam, S.; Routh, B.; Rurka, M.; Con, G. Family Networks and Psychological Well-Being in Midlife. Soc. Sci. 2017, 6, 94. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci6030094

Gilligan M, Suitor JJ, Nam S, Routh B, Rurka M, Con G. Family Networks and Psychological Well-Being in Midlife. Social Sciences. 2017; 6(3):94. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci6030094

Chicago/Turabian StyleGilligan, Megan, J. Jill Suitor, Sangbo Nam, Brianna Routh, Marissa Rurka, and Gulcin Con. 2017. "Family Networks and Psychological Well-Being in Midlife" Social Sciences 6, no. 3: 94. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci6030094