1. Introduction

Situated on a bridge over Buckland-Hollow Brook near Ripley in Derbyshire is a plaque (

Figure 1) that identifies the site as near to where a deadly shooting occurred in 1817, during an event known as the Pentrich Revolution. In a vain attempt at overthrowing the government of the day, a desperate group of local men marched on Nottingham, only to be routed by a troop of dragoons at the site of what is now the IKEA retail park. The authorities took the opportunity to make an example of the would-be revolutionaries and their families, who received punishments ranging from execution, transportation, and imprisonment, to the destruction of their homes and banishment from their communities.

As an artist with an interest in social history, and with the bicentenary of the events taking place in June 2017, I felt impelled to compose a soundwalk to mark the occasion. Defined by Westerkamp (

McCartney 2014, p. 218) as ‘any excursion whose main purpose is listening to the environment’, the soundwalk has become a device through which many artists are exploring space, combining purposeful listening with mobility.

Schafer (

1994, p. 213) describes the use of scores or maps as means of drawing attention to unusual sounds and ambiances, and specifically identifies ‘ear training exercises’ designed to focus the aural attention. The observational and reflective aspects of sound recording, involving decisions on (1) what to record and (2) what may emerge in the subsequent re-listening, can offer detailed information on what often passes unnoticed. My approach is rooted in

Perec’s (

2010, p. 51) concept of the ‘infraordinary’, involving the re-purposing and re-arrangment of sonic ‘oddments left over from human endeavours’ (

Lévi-Strauss 1962, p. 12). Whether inadvertently captured in the background, or deliberately recorded, much of this material is born of the everyday, the slippage of time between recording and playback providing a space for its contemplation. Soundwalks establish a frame through which the relentless processes of change can be both acknowledged and celebrated.

Westerkamp’s overarching definition of the soundwalk above can be nuanced to reflect the multifarious approaches of its exponents, as medium and technologies develop. Mine involves using digital recording devices to capture sounds along a selected route, these being re-edited via a computer into a composition, to be shared together with a group of people walking the original path. The digital and apparently ‘clean’ technology of the mobile phone or iPod works in combination with the determinedly analogue and physical process of walking, augmenting what passes for reality. The seemingly limitless malleability of digital sound allows the affective capacities of sounds to be heightened during the editing process and re-enacted in the gestalt of the soundwalk experience. The simple act of replaying a previously-captured recording in its original location may be sufficient to create a ‘schizophonic’ disturbance, described by

Bosma (

2016, p. 309) as ‘being in two sound worlds at the same time…a disturbance of auditory cause and effect’. Bosma proposes sound recording as a means of raising awareness of environmental sounds and, significantly, of the listening process itself.

I have been devising observational walks since 1996 and soundwalks since 2007, from urban contexts (to which I attribute the prefix ‘OpenCity’, to reflect the notion of a permeable and readable city) to rural settings and what lies in-between. In May 2016, already mulling over how to approach the composition of a soundwalk based upon the Pentrich revolution, I noticed a poster in the village indicating that plans to commemorate the revolt were already well under-way. I duly made contact with the organising committee, who accepted my proposal for a series of soundwalks. For the purposes of this article, which is not intended as a survey of the field, I have taken the first of these, based around the village of South Wingfield, as a case study. Drawing upon this walk and the specificities of my soundwalking practice, I hope to offer some wider thoughts on the potentialities of the medium.

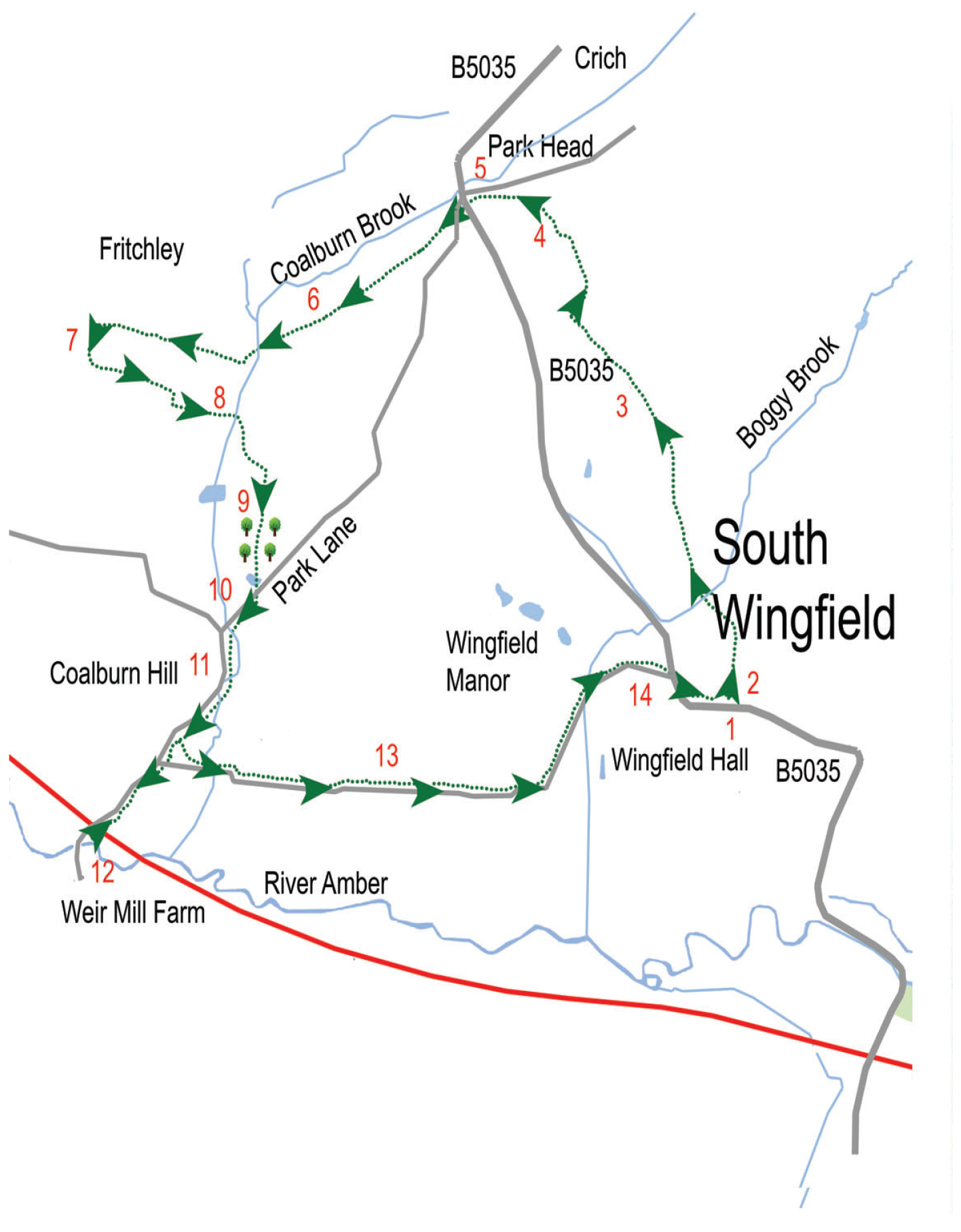

Although I would ordinarily establish soundwalk locations and routes through my own preparatory site visits, on this occasion I selected three from 18 already devised by local historians and guides for the Pentrich bicentennial commemorations. The walks around South Wingfield (

Figure 2), Pentrich and Giltbrook were each centred upon significant locations within the narrative of the original march as it proceeded towards Nottingham. Each of these walks crosses a variety of terrain, across tarmac and dirt track, and including areas of residential and agricultural land. I designed the three soundwalks to be experienced sequentially, the better to evoke a cumulative sense of foreboding, isolation and exposure, as fields and farms become increasingly carved up by roads and railways, culminating in the vast IKEA car park that lies adjacent to the dual carriageway of the A610.

Williams (

2016),

Gifford (

1999) and others have debunked romanticised notions of the English landscape as perpetually secure and unchanging, arguing that such representations obscure long-standing tensions within the social fabric.

Macfarlane (

2015) has described the English landscape of the stories of M.R. James as ‘constituted by uncanny forces, part-buried sufferings and contested ownerships’ and

Edensor (

2002, p. 133) critiques the ‘specific ways of remembering the pasts of places’ that the heritage industry chooses to apply, as authorised and mainly monocultural mythologies crowd out alternative narratives of our collective past. The English countryside of 1817 and the present day appear to have significant issues in common, including the consequences of land ownership and usage, absent owners and unemployment. Several contemporary artists are probing such political issues through locative sound, for example

Curtis’ (

2015) ‘Trespass’ app that encourages users to experience Freeman’s Wood on the edge of Lancaster, and to ‘decide for themselves whether they will trespass the boundary to fully access the audio content’.

Inevitably, one is led to speculate on what might have changed in the past 200 years, through periods of industrial revolution, post-industrial decline, and the information revolution. From consulting old maps, it is evident that the local landscape of the early 18th century featured canals, although not yet the railways nor the busy roads that now bisect it. Would the large quantity of litter scattered amongst our contemporary greenery offend the eye of an inhabitant of late Georgian England? How might they respond to the ubiquitous machine noise, especially the road traffic, of our present day? When imagining the soundscape as an unspoiled idyll, it is pertinent to remember the noisy trades of the period, such as cotton mills, as well as the heavy industries of quarrying and steel production. One might also consider aspects of contemporary life perhaps familiar to the revolutionaries, such as the infiltration of protest movements by government spies and agent provocateurs. What took place in this corner of Derbyshire resonates within our 21st century social and political culture, evidenced through its ongoing commemoration by the local community. The Pentrich soundwalks that I analyse through this article form a part of this process.

2. Spatiality

The four categories of lived experience identified by

Max Van Manen (

1990, p. 106)—spatiality, temporality, corporeality, and relationality—offer a series of prisms through which to consider the Pentrich soundwalks. His concept of spatiality references our phenomenological experience of lived space, including its psychological and physiological dimensions. My approach to initial reconnaissance of the lived space of the soundwalk is to allow myself to be led by the ‘attractions of the terrain’ (

Debord 1958) as I engage in acts of psychotopological ‘dowsing’ for potential sites and pathways. In performing this task, I alternate between drift and design, trying to inhabit a liminoid state of lostness, apart from social and strategic concerns, while keeping in mind the end goal of a practicable route. I attempt to tread lightly and not impose myself on a site, adopting the medium of sound as, arguably, the lightest form of touch. I routinely find myself in locations that are in some sense ‘contested’, or considered non-places (

Augé 1995), such as retail parks and roadside verges.

Lefebvre (

1991, p. 26) claims social space to be both a means of production and of control, and hence of domination and power. In common with many other artists, social space has thus become the arena within which I choose to site my work.

Eno (

2004, p. 128) describes the ‘detachable aspect’ of recorded sound, the capacity of an original ‘ambience and locale’ of a recording to be transposed into any situation. Placing the emphasis upon sound in space and manipulating its capacity for signification offers the potential to extend familiar psychogeographic discourse.

Shklovsky (

1917) proposed making ‘objects unfamiliar…to increase the difficulty and length of perception because the process of perception is an aesthetic end in itself’. Defamiliarisation has become a well-established artistic strategy to challenge and direct perception. Within my practice, I apply this towards a more critical relationship with place, in which the familiar can become strange, one becoming something of a tourist in one’s own locality.

Walking is a political act, and, both philosophically and literally, an approach, a way of encountering the world. It can be motivated by various interests and can take diverse forms, such as practical resistance to the ubiquity of motorised transport. My own perspective is based upon antipathy towards the control of personal freedom and mobility and the commodification of a populace. I attempt to resist homogenising influences within public space and to animate my journeys through it by directing my attention both internally as well as out into my surroundings. Initiatives such as the ‘slow movement’ (

Honoré 2005) cultivate more mindful approaches towards our relationships with the environment. A pedestrian is an active body, moving through space, and in control (if applied) of pace and decisions: whether to pause or investigate. Walking, according to

Debord (

1955) focuses ‘on the environment at hand’ and changes in ambiance.

Sinclair (

2003, p. 4) writes of walking as ‘the best way to explore and exploit the city...drifting purposefully is the recommended mode, trampling asphalted earth in alert reverie, allowing the fiction of an underlying pattern to assert itself’. The anticipation of an encounter, a ‘possible rendezvous’ (

Debord 1958) can produce in a subject a state of receptivity to their surroundings.

Soundwalks can be considered a form of mapping exercise, both in relation to the reiterative process of listening to, gathering and assembling sounds, but also in the form of the plethora of ‘live maps’ created by participants, responding to both the tangible and associative features of the environment.

Schafer (

2004, p. 37) described the world’s ‘macrocosmic musical composition’, available to all through the simple performance of active listening. Upon arrival on site, I typically use binaural microphones to gather baseline recordings along the entirety of the walk, to capture what is a unique series of moments in time and space. Despite the limitations inherent in all maps, these recordings provide fragments that can be reconstituted to form new ways of approaching space. The placement of sound within a specifically chosen listening space can then add a critical layer to the mix, such as the cacophony of exotic birdsong in the trees lining an urban boulevard. The most successful resonances seem to occur when unexpected sounds or events enter unbidden into the experience, creating a dynamic interplay between recorded and ambient sounds—to this end people are encouraged to listen via in-ear or on-ear headphones (not the over-ear variety).

The introduction of the Walkman allowed acousmatic sounds (recordings already detached from their source) to be further explored, misaligned, and permitted ‘the possibility, however fragile and however transitory, of...imposing your soundscape on the surrounding aural environment’. For

Chambers (

2013, p. 162), the Walkman is

part of the equipment of modern nomadism...it contributes to the prosthetic extension of mobile bodies caught up in a de-centred diffusion of languages, experiences, identities, idiolects and histories...as opposed to the discarded grand narratives (Lyotard) of the city, the Walkman offers the possibility of a micro-narrative, a customised story and soundtrack, not merely a space but a place, a site of dwelling. The ingression of such a privatised habitat in public spaces is a disturbing act.

Although the Walkman and its digital offspring have the capacity to shut out the external environment, such devices can readily be turned into means of animating our surroundings, facilitating novel forms of interaction. For

Cardiff (

2002), the alienation for which the Walkman has often been criticised is mitigated in the soundwalk by the connections it can form between ‘the visual, physical world and (the) body’. The brain seeks coherence, utilising its capacity for ‘unconscious inference’ (

Levitin 2006, p. 105) towards the construction of a credible world. This world is to some extent a constructed one, formed of a connective tissue of ambient and recorded sound upon which each soundwalk is built, edited to produce a convincing internal logic. A soundwalk’s soundtrack can be listened to detached from the site or played to accompany walks in locations other than those it was extracted from and designed for. However, in such circumstances, its effectiveness becomes compromised, apart from the occasional coincidences thrown up by any such random placement.

O’Rourke (

2013, p. 39) has described listening to Cardiff’s soundwalks while seated at a computer as ‘like viewing reproductions of paintings’ and that ‘isolated excerpts cannot replace perceiving the binaural sound in the setting for which it was conceived’.

The suffix ‘scape’ denotes a wide, possibly panoramic, conception of space, and when considering a landscape, we can adopt detached or embedded perspectives (

Wylie 2007, pp. 3–6). The 360-degree visual and heard experience of a soundwalk invites an expansive, individuated and critical response. It can arguably be considered an expanded form of cinema in its manipulation of reality through sound and image, yet generating direct physical experiences within the panoramic moving or static body.

While Cardiff (

2002) does not believe we have yet outgrown the cinema screen, she identifies a trend towards greater immersivity. Through her audio walks she states that she wants people

to be inside the filmic experience and have the real physical world as the constantly changing visuals of the screen. Every person will have a different experience of the piece depending on what happens around them or where and when they walk. I want the pieces to be disconcerting in several ways, so that the audience can’t just forget about their bodies for the duration of their involvement like we do in a film.

The soundwalk can be seen to place the participant into an especially ‘live’ moment, in which what we might consider to be ‘reality’ is augmented by sonically-induced interior projection. According to

Chion (

1994, p. 37), an augmented, ‘third space’ is born out of a dialectical relationship between recorded sound and phenomena encountered in the land/soundscape.

Burgin (

2004, p. 144) himself claims sound to be ‘a projector, in the sense that (it) projects meanings and values onto the image’ and he describes Barthes’ ‘inner souk’ of involuntary thoughts, creating a ‘unitary field’ in combination with the ‘noise of immediately external surroundings’ (

Burgin 2004, p. 15).

Within the contemplative space of a soundwalk, sound readily becomes ‘attributed to elements within the field of vision’ (

Chion 1994, p. 68). All can become encompassed within the frame of the soundwalk, often producing the disconcerting sense that elements such as passers-by have been deliberately placed within the experiential frame by the artist.

Counsell (

1996, p. 200) states that the ‘law of the text’ is ‘founded in the audience’s assumption that the event proffers meaning which is both intentional and organized...thus audiences often “find” coherent meaning even in accidents, “signs” which are unintentional’. The audience’s assumption of coherence leads to opportunities for exposure of the artifice behind the creative process. My occasional placement of inappropriate and even theatrical elements is designed to undermine such credibility and to draw attention to and demystify the constructed nature of the soundwalk experience, and by extension

all experience. Unlike the seductively comfortable cinema auditorium in which we can safely enter other worlds, an illusion broken by the occasional intrusion of our fellow audience members, the soundwalk produces a similarly liminal experience. However, the soundwalk participant is absolutely located in the real world, and with all-too-real consequences, especially from road traffic, to negotiate.

3. Temporality

Van Manen (

2011) defines temporality as subjective, as opposed to clock time, in recognition of its relativity and malleability. While the initial baseline soundwalk recording, captured in the initial period of working on-site, constitutes a raw sound file of a particular duration, it occupies a more fluid state within the experience of the listener. The recording operates as a tentative sonic map of a time and space, a moment occupied by the host of parties (animate and otherwise) that happen to share it. When edited together with recordings from other times and/or spaces, each can upset the coherence of the others. When the resultant sound collage is re-introduced into the unpredictability of the here-and-now at the point of sharing, the effect is further enhanced. An imaginarium is opened up on our contemporary world in which, for example, the not dissimilar sounds of traffic and crashing waves might lead to imaginative speculation on the sea reclaiming the city, in its future, its distant past, or some parallel universe. As in Resnais and Robbe-Grillet’s film ‘L'Année dernière à Marienbad’ (1960), we are faced with a composite that resists deconstruction, unable to ‘tell what is flashback and what is not’ (

Deleuze 2011, p. 118). In describing Robbe-Grillet’s work, Deleuze goes on to state ‘there is never a succession of passing presents but a simultaneity of a present of past, a present of present and a present of future, which make time frightening and inexplicable’ (

Deleuze 2011, p. 98). During a soundwalk we can veer between perceived positions of stability and of temporal drift.

Soundwalks map the present, but also juxtapose the recent and distant past, enabling us to navigate temporalities and to imaginatively and sonically travel through time, functioning as snapshots of forever-changing land and soundscapes, through evolving technologies, communities, and social practices. To return to a soundwalk in the days, months or years after its composition is to encounter the passage of time, as residual sounds re-surface in combination with the ever-changing sounds in the present. There is a strong archaeological dimension to soundwalking practice, a peripatetic form of ‘dig’, unearthing traces in a deep map of what reverberates in the molecules of air above and around as much as beneath the surface of the soil.

Shanks and Pearson (

2001, p. 64) describe deep maps as

attempts to record and represent the grain and patina of place through juxtapositions and interpenetrations of the historical and the contemporary, the political and the poetic, the factual and the fictional, the discursive and the sensual; the conflation of oral testimony, anthology, memoir, biography, natural history and everything you might ever want to say about a place.

A soundwalk can incorporate all of the above, in forms as varied as the sonic meditation and ‘listening exercise’ to the GPS-located; from the adoption of a strict relationship with a particular site to more flexible approaches. My own application tends towards a synchrony between the features of the recording and those of the site, hence my predilection for leading the walks and acting as ‘pacemaker’. The sensation of being in time with the myself of then, be it several weeks or hours ago, is compelling, in some way akin to that of standing where a significant event took place, hovering between eras, in the company of lives long since past.

For me, synch points and the feeling of being in step are akin to participating in a successful group improvisation. However, as with moments in improvisation, the feeling is a fleeting one, and seemingly at the whim of chance. One can only attempt to create the conditions, placing oneself in the approximate spot where such moments might occur, like a photographer hoping to capture a lighting strike. When in sync with my original footsteps and the gestures of the performance of recording, I am effectively re-performing my actions of the earlier walks, made in the recording and subsequent testing of the walk.

Soundwalks offer a means of simultaneously inhabiting multiple times and places, opening portals for imagined possible worlds. At root, the practice acknowledges the inevitable nature of change, evidenced through the traces we pick up and leave behind.

Fisher (

2013, p. 3) alludes to time ‘breaking in’ via portals in the landscape, and anachronisms, images and figures from the past, appearing unbidden into a haunted landscape. The status of such portals is uncertain, with regard to where they lead to, or from, and whether they form potential routes of escape or deeper entrapment.

I determine the pace for participants in the soundwalks, forcing the pace by striding ahead, or by introducing equally uncomfortable periods of dawdling or pausing, stretching time through slow or controlled movement through space. The protracted gaze alights on objects, images register in the brain, are noticed and pondered, and a meditative stillness occurs in the encounter between oneself and external phenomena. As Frédéric Gros writes, ‘days of slow walking are very long, they make you live longer, because you have allowed every hour, every minute, every second to breathe, to deepen...this stretching of time deepens space’ (

Gros 2006, p. 37).

4. Corporeality

Sonnenschein identifies the capacity of the inner ear for sensing movement and contrasts ‘traditional movie theaters (that) keep you steady in your seat’ (

Sonnenschein 2001, p. 88) with theme park rides. To a less dramatic extent, soundwalks can be seen to demand the engagement of the entire body. The use of binaural technology, in which sound is captured as though via the sensory array of the human head, results in a subjective and highly spatialised recording, the recordist effectively becoming a performer, their movement detectable in the final recording when experienced through headphones (

Carlyle 2013, p. 19), and using their body as a vehicle through which to investigate the soundscape. The development of affordable and mobile audio technology that both captures and replays an auditory environment has been transformative, in that the acoustic ‘soundprint’ of a space can be effectively captured, as can something of the sensibility of the recordist, about whom we can subconsciously gather information through the sound of their breathing and footsteps, or their involuntary utterances. As human beings, we readily fall into mimicking one another (

Stel 2016, p. 28), as evidenced through the impact of the sound of another person’s breathing upon our own respiration. In the re-performance of others’ walks/acts, we embody the knowledge of how it feels to trudge across a landscape.

Pallasmaa (

2005, p. 42) identifies sound as an extension of the sense of touch. The experience of the soundwalk is, first and foremost, a corporeal one, the body our ongoing interface with the exterior world. We project ourselves, literally striding out into it, but also through its various sensory faculties touching, tasting, hearing that world. The body becomes a point of access to both outer and inner life, or as

Deleuze (

2011, p. 182) puts it, ‘the body is no longer the obstacle that separates thought from itself, that which it has to overcome to reach thinking. It is, on the contrary, that which it plunges into or must plunge into, in order to reach the unthought, that is life’.

As we go, traces are mutually and unexpectedly exchanged with the environments through which we pass (

Massey 2005, p. 118). When engaged in a soundwalk, one can readily sense the porosity between ourselves and what we encounter, that can almost appear to rise up to meet the eye. In

The Object Stares Back Elkins (

1997, pp. 46–48) bestows objects with agency, describing how they snare the gaze.

Bennett (

2010, p. 4) identifies an overlap between human being and thinghood, and the ‘energetic vitality’ within what is generally seen as inert. The capacity to experience our environment at such a granular level is evidently not restricted to participants in a soundwalk. However, by remaining silent and allowing oneself to be guided, stepping out of everyday concerns to interact with one’s surroundings, our senses can be opened. Bennett celebrates the capacity ‘to be surprised by what we see’, implying the richness of experience that can be derived from focussed attention.

O’Sullivan (

2006, p. 1) describes such encounters as ’a rupture in our habitual modes of being and thus in our habitual subjectivities. It produces a cut, a crack. However...the rupturing encounter also contains a moment of affirmation...a way of seeing and thinking this world differently’.

The act of walking can be conceived as methodology, an approach to the world. It produces embodied knowledge through direct physical contact with an environment. Its rhythmic nature has the capacity to draw the walker into a reflective state of mind.

Jarvis (

1997, p. 68) writes of a ‘hypnotically self-absorbed state’ of reverie that can be generated through the regular stride pattern of the act of walking. Likewise, states of daydreaming, focussed attention, discomfort and boredom may all be felt in the course of a single soundwalk. Along with periods when the mind may become ‘liberated’, there will be others when awareness of bodily sensations such as weight, breath and pressure become acute. Taking South Wingfield as an example, one may set out with a sense of anticipation and collective spirit that, as one crosses exposed tracts of land, turns to vulnerability and of feeling surveilled. Moments of confusion may arise concerning which path to take. (

Figure 3). Walking in single file along paths that have become overgrown with vegetation can readily arouse impatience and frustration. Sudden shocks, embedded within the recording, create surges in adrenaline. As the walk progresses and fatigue sets in, there may be a longing for the comforts of home.

As an artist, in sharing the walk, I experience a sense of taking over the bodies of participants, hijacking them in order to offer what may or may not prove to be fruitful experiences. Sound artist Andrea Polli (

Carlyle 2013, p. 23) likens headphone listening to ‘taking over someone’s head’, raising the issue of power within the artist/audience relationship. Janet Cardiff has stressed the need to ‘ground the listeners’ body physically’ (

Cardiff and Schaub 2005, p. 33) and among participants there may well be feelings of resentment and irritation directed towards the artist and/or pacemaker. At the outset of a walk, instructed to stay close to the pacemaker in order to encounter sounds in sync with points along the route, they are often disrupted from what may be their own familiar and comfortable walking pace. While it can feel good to allow oneself to be guided by another, the forced pace of a soundwalk (fast or slow depending upon circumstances) can also be seen to override participants’ control.

5. Relationality

My adoption of the medium of the soundwalk grew out of my involvement in free sonic improvisation, itself born out of frustration with other musical forms that, to me, felt contrived and predictable. Through the incorporation of chance, and collaboration with other (often untrained) players, I was able to step back, confident something worthwhile was likely to occur within the space that had been created, as it invariably does between the baseline recording and live experience of the soundwalk. Akin to the propositions of Situationist architecture, in which spaces enable ‘the unexpected and the unplanned...(and)...spatial configurations...there is always an element of chaos’ (

Massey 2005, p. 112), itself something to be nurtured and celebrated. The soundwalk combines sound recordings of objects into ‘organised collage with the same type of emotional trajectory...as traditional music’ (

Levitin 2006, p. 14). Into this process, the element of chance sets up a benign collision of factors—time, space, participants, passers-by, mood, weather conditions—all co-conspirators within the walk. In order to incorporate the accidental, it becomes necessary to adopt as light a touch as possible. Although the intention may be to activate associations and memories in participants, it would seem inappropriate to over-determine the experience and consequent reading by participants. As co-composers, they complete the soundwalk, bringing their own associations and capacities for extracting meaning from the sensory information that materialises, much of which will necessarily be beyond the artist’s control.

Within the unfolding soundscape, what

Burgin (

2004, p. 150) terms the ‘super field’, of ‘ambient natural sounds, city noises, music, and all sorts of rustling that surround the visual space’, I often feel compelled to pause and listen in order to better appreciate

Schafer’s (

2004, p. 37) ‘macrocosmic musical composition’. Discordant or harmonic, it reflects the world that we inhabit. However, the indiscriminate and unconstrained expansion of noise still retains the capacity to offend the ear, and lacking ‘earlids’, we are somewhat at the mercy of whatever soundscape is imposed upon us.

Schafer (

1994, pp. 74–78) also described noise as a representation of power, of having the authority to generate it without censure. As the founder of the discipline of acoustic ecology, his original proposal for the soundwalk was based upon noticing, with the ultimate aim of leading us towards taking greater responsibility for the soundscape.

I consider the sites in which I work as co-authors, providing the content and context for my practice.

Massey’s (

2005, p. 23) description of ‘dynamic simultaneity’ provides a means of reflecting upon the practice of soundwalking, in which space is never empty but replete with lives and associated material, everything in a perpetual state of becoming. A soundwalk composed of a group of people, itself a multiplicity of trajectories, forms a temporary locus for multi-sensory experiences within the here-and-now. Soundwalks disrupt the flow of time and the apparently smooth surface of space, opening up its (often troubled) histories, potential futures, or simply calling into question the processes through which versions of these histories become authorised. Participants are invited to look and hear afresh, at what lies in plain sight and hearing within their everyday environment, as though for the first time.

The generally small and ambulant party engaging in a soundwalk is defined by its collective purpose. As expressed by

Lee and Ingold (

2007, p. 82), ‘manifested as a shared rhythm of footsteps and bodily aspect, there is a distinctive sociality in which the togetherness of the walkers has meaning for themselves and for people around them’. Doreen Massey’s assertion of space as ‘a simultaneity of stories so far’ (

Massey 2005, p. 9) places us at a confluence, interconnected along the paths on which we walk. At times, when confronted by a group of soundwalk participants, the effect upon passers-by can be pronounced, as we pass through and disturb space. As mentioned earlier they, among other ‘things’ caught within the frame of the soundwalk, become absorbed into its apparent coherence. Participants in a soundwalk perform a liminoid rite of passage, according to Arnold van Gennep’s formulation of the stages of separation, transition and incorporation (cited in

Turner (

1982, p. 80)). The formation of a group united around such a shared experience generates communitas, while during the walk the wearing of headphones can engender contrasting feelings of isolation and alienation. As participants together, we both form a group and yet are ultimately alone, extremes that can be accentuated within the editing process through the addition of sounds that reference a group or an individual by their footsteps or breathing. Participation involves the sharing of an experience, but also of encountering personal resistances, as power and decision-making are relinquished in engagement with the spirit of the artwork and the typical response of trust in the artist. Although ‘just a walk’, at times the soundwalk experience can become an all-consuming quest, overtaking participants’ bodies and minds.

Although they can often be experienced independent of the artist, my preference is to lead soundwalks in person, principally because of the potential for dialogue with participants. The post-walk discussion not only gives the opportunity to share feelings about the walk but also concerning the spaces through which we have passed, often leading to wider debate. In a sense, we are collectively performing participatory action research in which my role is that of a facilitator of the research/action process (

Jupp 2006, p. 216). A further and important function of the post-walk discussion is to allow participants to reacclimatise, to re-integrate with the world.

6. Conclusions

My understanding and appreciation of the soundwalk is necessarily framed by my own experience of the medium as applied within my own practice. Digital sound’s seemingly infinite malleability, together with the breadth of places, and the stories that can be told about and through them, lead me to believe in its potential. As it gains traction within public consciousness, the soundwalk may yet become an established form of arts practice, despite lacking some of the qualities, such as replicability, that make for easy commodification. Although I am particularly interested in bringing a group together at the same point in time and space, many exponents allow their audiences to undergo the experience independently, and the use of geo-located apps that incorporate sound playback will surely play a significant role in the medium’s development.

I am especially keen to explore soundwalking’s potential as a critical tool for the speculative consideration of the processes of perception, of the art experience itself, and of the artist/audience relationship. I have also directed it towards such subjects the English countryside, failed utopias, post-industrial ruination, and the role of the tour guide. At root, a soundwalk is a reminder of time passing and the processes of change, although the negative implications of these may be mitigated by the richness of the experience of the here and now, derived from an embrace of slowness and cultivation of a mindful attitude.

The soundwalk experience shares significant features with cinema, such as in the co-constructive relationship between sound and image and the taking of imaginative journeys into other worlds. The cinema experience may be moving towards greater immersivity, yet the consequences within its safe and seductive comfort currently remain limited. Beyond the auditorium screen, a soundwalk provides a far less bounded, even panoramic perspective, placing the participant in a specific setting within which they may be taken through diverse (and possibly contradictory) states.

While it provides a means of appreciating, across two centuries, something of the experience of the Pentrich marchers, could the soundwalk be utilised as a means of engendering understanding between contemporary communities through the creation of dialogic space? Can a soundwalk provide agency for people, in particular those who are currently marginalised, through which to explore their relationship with place and self-/shared identity? Might the privileged status of art provide scope for it to become an effective means of social activism? Extending beyond its origins in acoustic ecology, might the soundwalk be applied in a deeper appreciation of our shared environment, and adoption of a more responsible position towards it?