Factors that Influence Intake to One Municipal Animal Control Facility in Florida: A Qualitative Study

Abstract

:Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

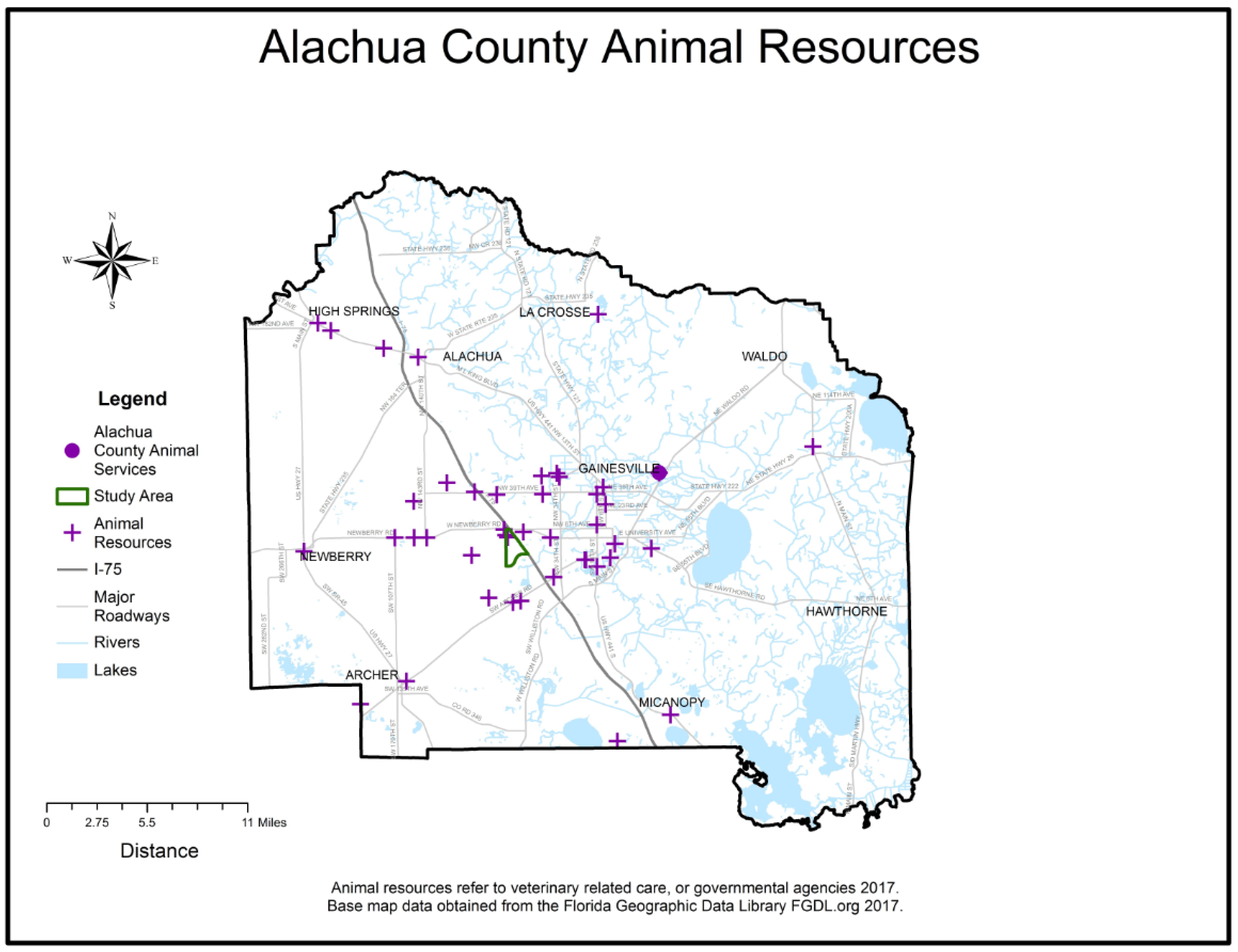

2.1. Animal Intake Data Collection, Cleaning, and Geo-Mapping

2.2. Field Observations

2.3. Semi-Structured Interviews

2.4. Analysis of Interview Transcripts

3. Results

3.1. Animal Intake

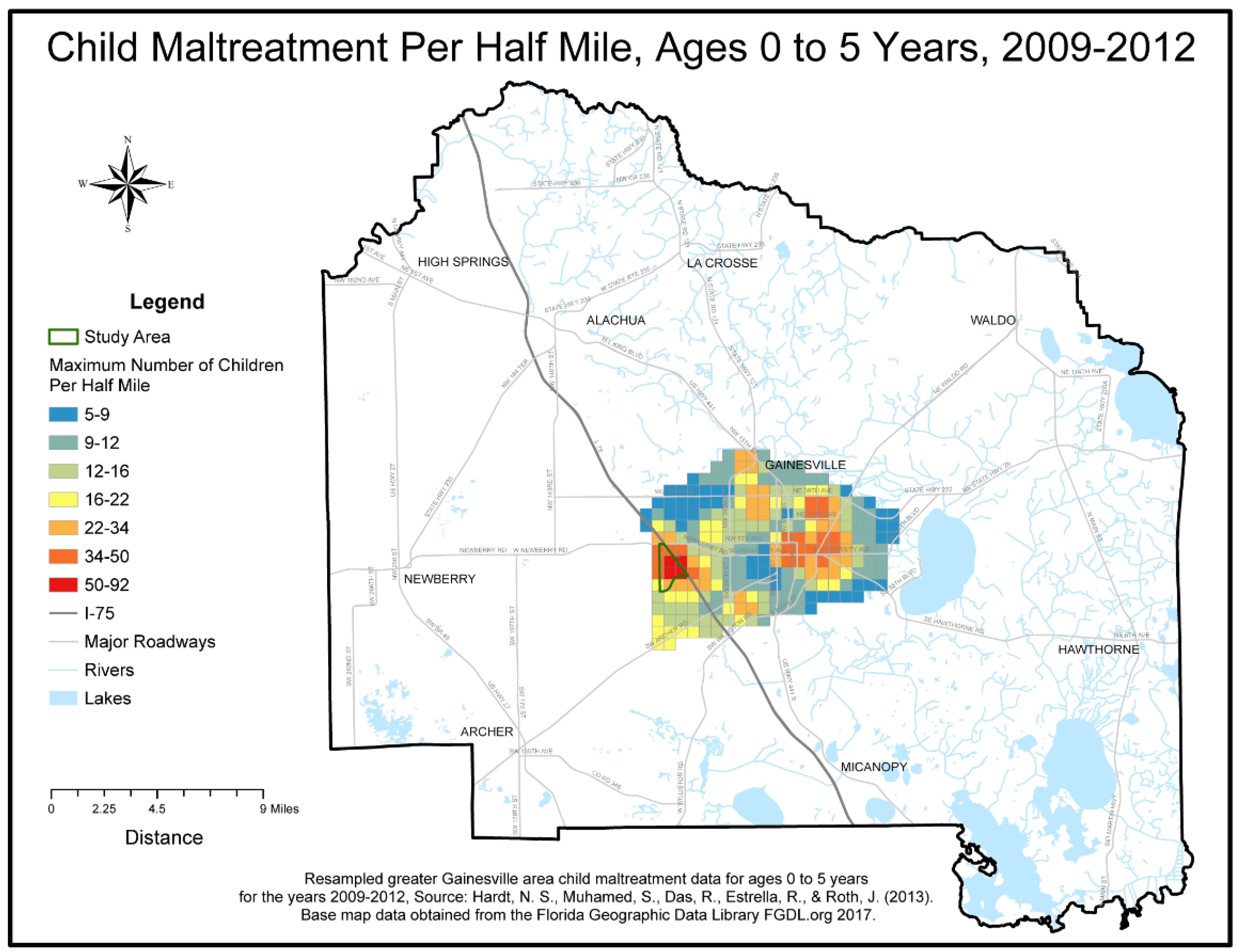

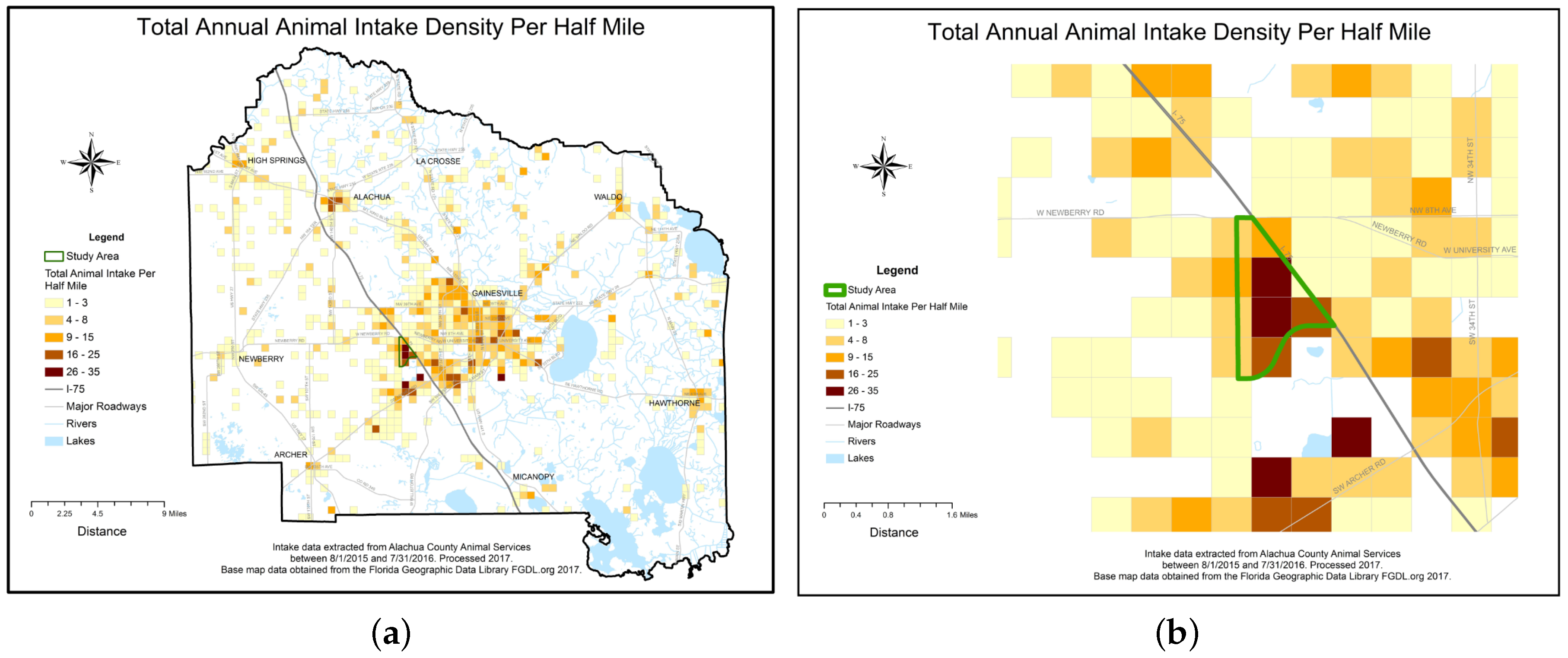

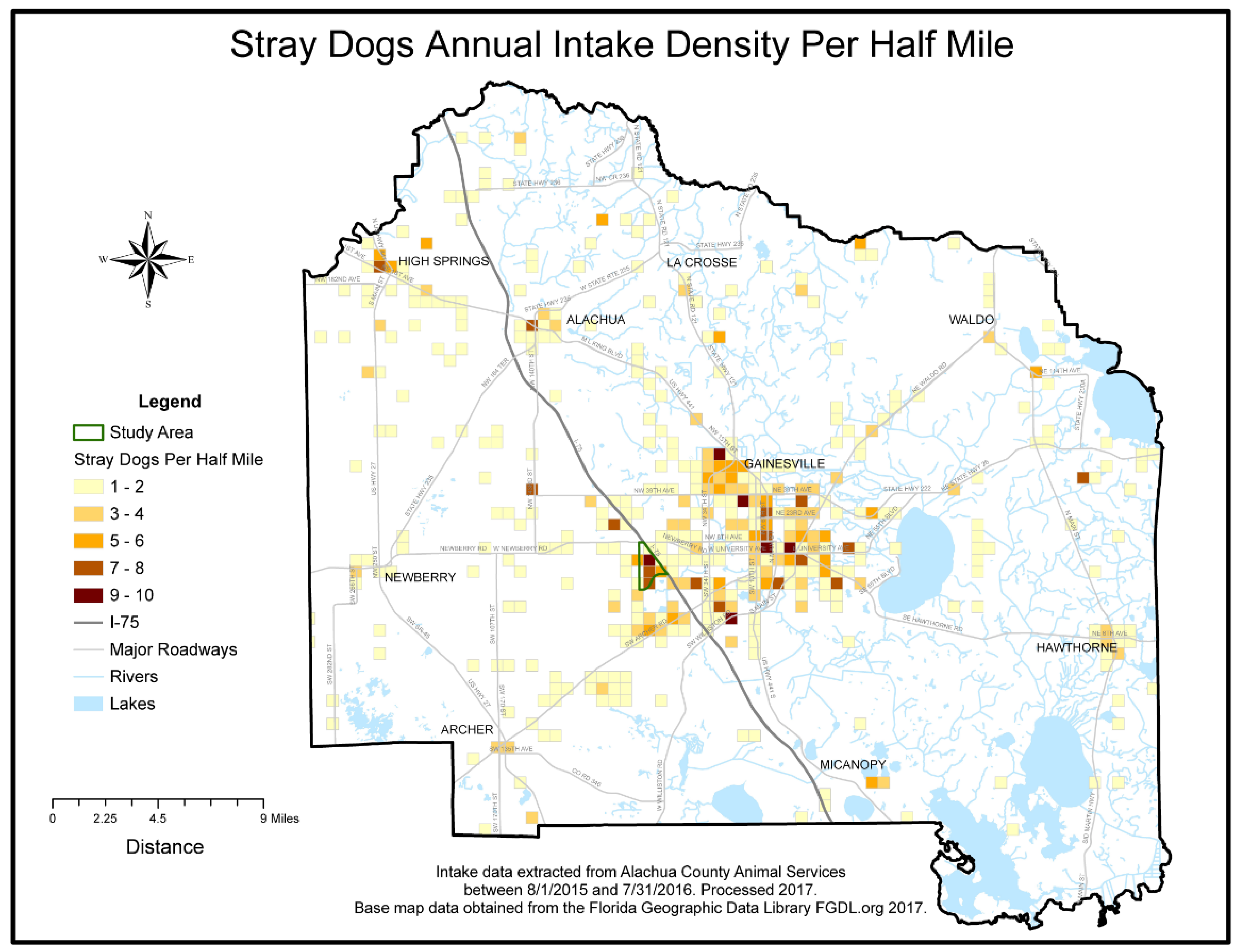

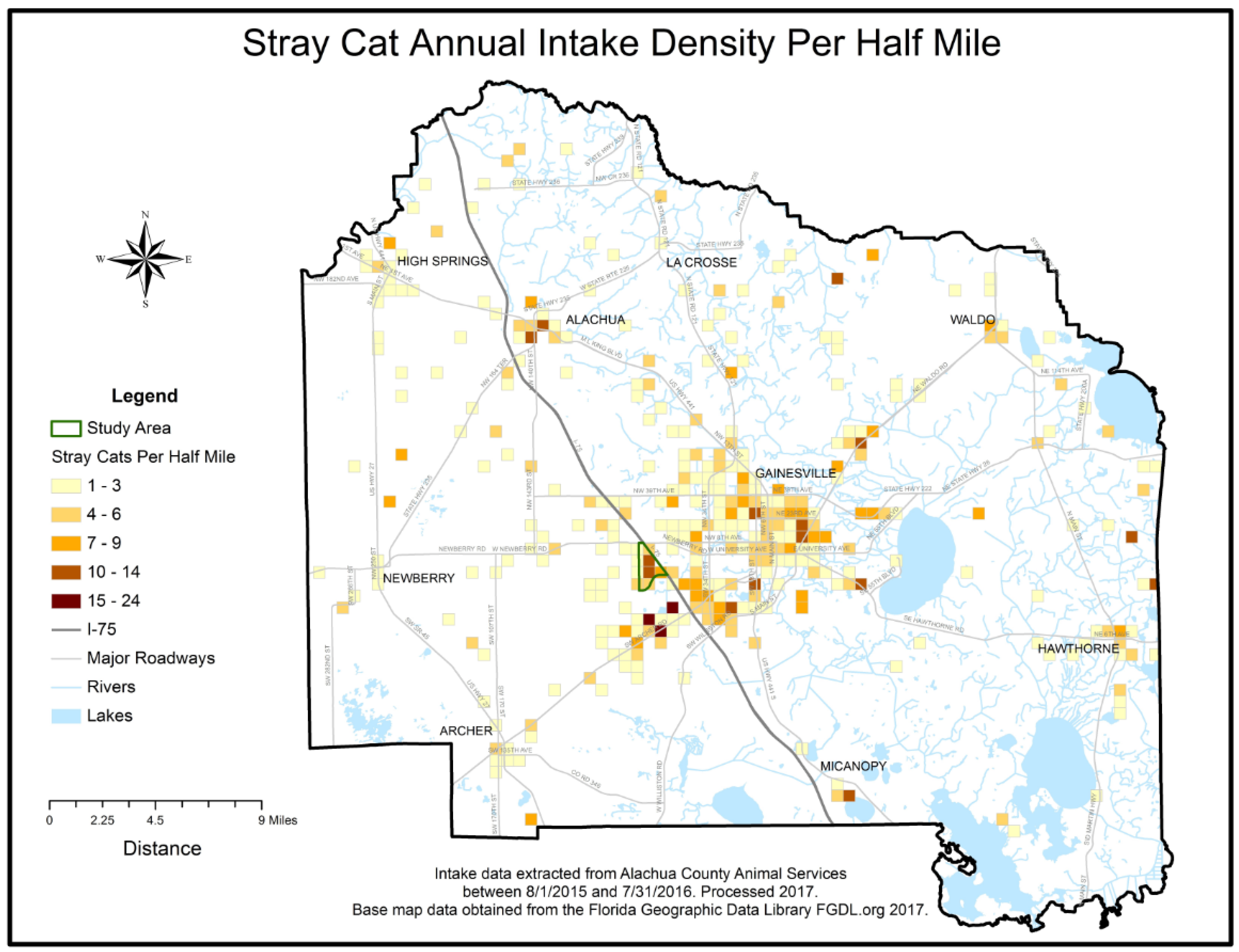

3.2. GIS-Maps

3.3. Field Observations

3.4. Community and Participant Demographics

3.5. Interview Findings

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Observation Field Notes Guide

- Schedule an initial one-hour ride-along with an animal control officer or community service officer who is familiar with each GIS-mapped neighborhood to be observed.

- Prior to the initial observation session, prepare to compile FIELD NOTES for each neighborhood that will include:

- the day of the week and date of the initial observations

- the scheduled start and stop times of the initial observations

- descriptive name for each observed neighborhood

- the boundaries for each neighborhood to be observed

- who will be present for the initial observations, including your name as the observer

- Background information from the accompanying animal control officer or community service officer that describes their familiarity with residents and domestic animals of each neighborhood (What is their professional knowledge about each neighborhood? What are the common types of service calls they make in each neighborhood? Do they know of any particular challenges or issues faced by the residents or dogs and cats of the neighborhoods? Why do they think so many dogs and cats enter the county animal shelter from these locations? What do they think is needed to prevent dogs and cats from these neighborhoods ending up at the county animal shelter?)

- During the initial observation session in each neighborhood, and with the ride-along officer’s assistance, record or document in the FIELD NOTES evidence of/that:

- dogs and cats being kept as household or personal pets

- the neighborhood is pet-friendly

- dogs and cats being cared for as community animals or loosely-owned animals

- dogs and cats are viewed as pests or problematic in the community

- dogs and cats are viewed as products in the community (for breeding, gambling, fighting, selling, trading, etc.)

- specific neighborhood culture or language exists

- specific neighborhood socioeconomic status exists

- access to basic community services for people

- access to pet care and veterinary care services

- residents of the neighborhood feel safe

- special challenges/issues facing this community

The evidence you collect should note or document the presence or absence of such things as (sort of like a scavenger hunt):- Freely-roaming animals

- Pets on leashes

- Pet collars (and note types of collars, such as heavy chains, pinch, harness, etc.)

- Tethered pets

- Pet-feeding stations

- Pet-water bowls

- Pet-food bowls

- Pet housing

- Fenced yards

- Dog parks

- Animals feeding from waste containers

- Lost pet flyers

- Posted signs restricting animals

- Advertisements for "pet-friendly" housing or businesses

- Posted policies restricting breeds of dogs

- Public transportation

- Community centers

- Libraries

- Schools

- Churches

- Grocery stores

- Recreation areas

- Veterinary care centers

- Foreclosures

- Real estate for sale or for rent

- Whether people are active outdoors and estimate their ages

- Language used on posted signs

- Predominant housing type (apts/mobiles/single family/tents/dorms) and density of residences.

- Whether housing has bars on windows and doors

- “Community watch” or community protest signs

- Predominant types of businesses in neighborhood

- Other pertinent items, such as abandoned houses, construction, etc.

- After each observation session, take time to reflect on everything you observed or documented. What information do you still need? What questions remain? What concerns you about the relationships between people and pets in this neighborhood? Add a summary of your impressions of each neighborhood to the Field Notes.

- Compile the Field Notes, your summary, and debrief with the research team.

- Schedule follow-up observation sessions to each neighborhood with a partner who can drive while you compile Field Notes. The purpose of the follow-up sessions is to validate your initial observations on different days of the week and at different times of day.

- Plan to make a total of 4 observations in each neighborhood, including the initial observation session, which occurs on a: weekday during normal business hours; weekday evening; weekend day; and weekend evening.

- Plan any additional observations only if necessary to answer questions that arise during the sessions or to clarify data you were unsure of from previous sessions.

- Use the same format for your Field Notes as during the initial observation. Your follow-up sessions should each be one-hour in duration and serve to supplement the data you collect from prior observations.

- Reflect and write your summary notes after each session.

- Compile the Field Notes, your summaries, and debrief with the research team.

Appendix B. Interview Guide

- A. Read page one of the Informed Consent Document to each volunteer, or ask him/her to read page one of the Informed Consent Document.

- B. Have volunteer sign, date, and provide their mailing address on page two of the Informed Consent Document if they agree to participate.

- C. Collect page two of the Informed Consent Document and give page one to the volunteer.

- D. Ask the volunteer to create a personal identification code and remind them to note that code on their copy of the Informed Consent Document so they will have it in the future if they wish later to withdraw from the study. Volunteers create a person ID code using the following system:

- First letter of mother’s first name

- First letter of father’s first name

- Middle initial of volunteer

- Day of their birth (two digits)

- Q1. What is your personal ID code for participating in this interview?

- Q2. Please describe the location of this neighborhood and tell me whether you live or work here. (EXAMPLE: This is Haile Plantation. I work here.)

- Q3. If you live here, please describe the type of housing you live in: (EXAMPLE: is it an apartment, mobile home, condo, tent, dorm, assisted living facility, single-family home, etc.)NOTE: if they do not live in this neighborhood, skip to Q4.

- Q3A. How many people share your residence? (CHOOSE ONE: I live alone; I live with _______others)

- Q3B. Do any dogs or cats share your residence? (CHOOSE ONE: No, Yes ________ dogs and _______cats)

- Q3C. How many times have you moved (relocated your residence) in the past 5 years? (CHOOSE ONE: 0 times, 1–2 times, 3–4 times, 4–5 times, more than 5 times)

- Q4. If you work here, please describe what you do: (EXAMPLE: shopkeeper, clerk, law-enforcement officer, etc.)

- Q4A. Do any dogs or cats live at your place of work? (CHOOSE ONE: No, Yes _______ dogs and _______ cats.)

- Q5. How long have you lived or worked in this neighborhood? (CHOOSE ONE: Less than1 year, 1–5 years, 6–10 years, 11 or more years)

- Q6. What is your sex? (CHOOSE ONE: Male, Female, Other, or I prefer not to say.)

- Q7. What is your age? (CHOOSE ONE: 18–25 years, 26–30 years, 31–40 years, 41–50 years, 51–60 years, 61–70 years, 71–80 years, 81–90 years, 91 years or older)

- Q8. What is the highest level of education you completed? (CHOOSE ONE: I did not finish high school, GED or high school diploma, vocational certificate or some college, undergraduate degree, graduate degree (such as a master’s or PhD), professional degree (such as an MD or DVM), post-doc)

- Q9. How do you prefer to describe your racial and/or ethnic group? (EXAMPLES: Hispanic White, Non-Hispanic Black, Asian, etc.)

- Q10. What is your primary spoken or written language? (EXAMPLES: American English, Spanish, French, Chinese, Russian, etc.)

- Q11. What is the approximate annual income for you and your immediate family? (CHOOSE ONE: less than $10K, $11–20K, $21–30K, $31–40K, $41–50K, $51–60K, $61–70K, $71–80K, $81–90K, $91–100K, More than $100K.)

- Q11A. How many people are dependent on this income? (CHOOSE ONE: only me, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, etc.)

- Q12. How often do you have access to a computer and the internet for personal use? (CHOOSE ONE: Always, Never, only Sometimes--if chooses Sometimes, ask for an explanation for why)

- Q13. How often do you have access to a smartphone (cell phone) for personal use? (CHOOSE ONE: Always, Never, Sometimes—if chooses sometimes, ask for an explanation for why)

- Q14. How do you rate your physical health? (CHOOSE ONE: excellent, good, fair, poor)

- Q15. How do you rate your emotional health? (CHOOSE ONE: excellent, good, fair, poor)

- Q16. Have you ever had a partner try to control you? (CHOOSE ONE: yes, maybe, no)

- Q17. Have you ever had a partner of whom you were afraid? (CHOOSE ONE: yes, maybe, no)

- Q18. Have you ever had a partner who threatened you? (CHOOSE ONE: yes, maybe, no)

- Q19. Have you ever had a partner who threatened to hurt or kill your pet? (CHOOSE ONE: yes, maybe, no)

- Q20. Have you ever had a partner who intentionally hurt or injured your pet? (CHOOSE ONE: yes, maybe, no)

- Q21. Has concern about your pet’s welfare ever affected your decision-making about whether to stay or leave your partner? (CHOOSE ONE: yes, maybe, no)

- Q22. Tell me about any dogs or cats that you keep or care for.

- Q23. Tell me about any other dogs or cats that live within your neighborhood.

- Q24. Tell me about any issues or problems you have with the dogs and cats in your neighborhood.

- Q25. Tell me how you feel about breeding of dogs and/or cats in this neighborhood.

- Q26. Tell me how you feel about betting (gambling) on dogs and/or cats in this neighborhood,

- Q27. Tell me how you feel about buying/selling/trading of dogs and/or cats in this neighborhood.

- Q28. How would you feel about a neighborhood dog or cat being euthanized (put down) at the county animal shelter?

- Q29. Why do you think so many dogs and cats from this neighborhood end up at the county animal shelter?

- Q30. What do you think would help keep dogs and cats from this neighborhood out of the county animal shelter?

- Q31. Thank the volunteer for participating in this study and ask if you can contact them again to confirm the finding. (CHOOSE ONE: Yes or No)

- Q31a. If the answer is NO, this completes the interview.

- Q31b. If the answer is YES, ask them how to contact them when you are ready. NOT COLLECT THEIR NAME, you will refer to them using their personal ID code when you contact them—Record the phone number or other method they want you to use to contact them.)

Appendix C. Annual Animal Intake for Alachua County, Florida

| Count By Species and Age | Percent of 2901 Animals | |||||

| Intake Age | Canine | Feline | total | Canine | Feline | total |

| Adult | 1121 | 875 | 1996 | 38.64% | 30.16% | 68.80% |

| Juvenile | 77 | 291 | 368 | 2.65% | 10.03% | 12.69% |

| Unknown Age | 210 | 327 | 537 | 7.24% | 11.27% | 18.51% |

| Count By Species and Type | Percent of 2901 Animals | |||||

| Intake Type | Canine | Feline | total | Canine | Feline | total |

| Stray | 955 | 1279 | 2234 | 32.92% | 44.09% | 77.01% |

| Surrendered or Returned | 409 | 211 | 620 | 14.10% | 7.27% | 21.37% |

| Confiscated | 40 | 3 | 43 | 1.38% | 0.10% | 1.48% |

| Other Disposition | 4 | 0 | 4 | 0.14% | 0.00% | 0.14% |

| Total | 1408 | 1493 | 2901 | 48.53% | 51.47% | 100.00% |

Appendix D. Themes and Example Codes

| THEMES | Codes | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| CONCERNS | Animal Welfare | RCV12: I think we can’t take care of them, don’t breed them. You see them [indiscernible] you see now these guys out here, under the sun, and I’m like it breaks my heart to see a dog like that. He sits there all day chained to a tree. EEL05: Sometimes they don’t have shelter at night. They are not getting fed on a regular basis. Just whatever they can scrounge. MBE12: I know of a lady trying to help sell little Chihuahuas. I drove them to Missouri and was bottle feeding this one all of the way over. How cruel, taking it away from its mother early age. To each its own, but—I’m powerless. DAM18: Cats are in their apartment and dogs are in their apartments. Until they put them out on a chain outside. Well, they do let the pit bulls outside. Well, they’re pit bulls, and when you pass by, they start barking. Chaining them out there—I heard they ate a few cats when they got off that chain. |

| Personal Safety | MWA22: We ain’t in a very good neighborhood. JJD12: I’ve seen them [dogs in the neighborhood] but they’re not stray. Yeah they’re owned by others, yes ma’am. Yes, yes definitely [on leashes]. All but one. All but one they never have on a leash and I’m terrified of that dog. I’m just afraid of big dogs. I think it’s a pit. It’s like, um, like a pit bulldog. CLL12: I’m scared of anyone [dogs] that’s not mine. But for the most part I’ve never had a bad experience. MJM17: Because people don’t want to take care of their own animals. They just want to let them do whatever they want and that’s why dogs have to be—dogs and cats get put down because they want to attack people because they do what they want when they want to and when you try to change their habit you can’t. There are little kids around here. | |

| Money | CLL12: My neighbors have two dogs and it’s not the same situation. A small dog is like 6 months and really, really skinny. I try to feed sometimes but I can’t afford to feed it. JJD30: We did have to [pay] $200 [pet fee for cat in apartment]. That’s expensive for a cat. Like my husband back in the day, he used to work for (indiscernible). So [landlord] allowed us to pay him so much a month. We’re on limited income and have to pay the light bill and everything else, but he’s working with us. OHM29: The main problem when you have to pay the vet. The test is really expensive. I think maybe the community have to have options for veterinary care that’s free. Because one time I bring the pet to UF vet, they treat everything. It’s expensive, $2000. My son requested a loan from the college because he has scholarships. It doesn’t pay for [Indiscernible] he doesn’t want to lose the dog [Indiscernible] he wants to treat. It’s really expensive. Because my son is a student. I make eight hundred a month and we live alone. | |

| Health | EJM18: I would [have a cat] if I could. My daughter, she’s pregnant. The doctor told her (indiscernible). She can’t be around them. That’s the only reason I won’t bring the cat in. I wish I could open the door and bring them in. MOE20: It’s my daughter’s dog. My daughter, I told you she has got the heart transplant. They all fell in love with her. She fell in love with the golden doodle that used to come to the hospital visiting. So, they all got together with the breeder, and the breeder gave her the golden doodle, and throughout the—all the doodle owners, they all pay for everything for my daughter for the dog. They pay for the vet, groom, feed. They take care of it all. Once it gets to be a year old, it’s going to be put on as a service dog. They are paying for everything. It’s something for my daughter. But right now, it’s my dog. It bites too much right now. DAM18: I had two dogs and they took them to [low-cost vet clinic] and she took because I had hip replacement and she took one of my puppies away because I was sick and can’t take care of the puppy. And I still could have took care of the puppy. No. I wasn’t, [OK with that] because you know it was my dog and she kept convincing me that I—and I had to go to surgery. I don’t have any family except my boyfriend. It was hard—I should have took her back. | |

| ATTITUDES | Animals are pets | JJD30: If you have got an animal, take care of it. Keep it inside. Like me, my cat, that’s my girl. I take care of her. She’s a member of my family. Everybody in the family loves her. If she wants to go out and use the bathroom, she will sit there. So, I keep my spray bottle because there’s a calico and a black and white one. The other day they literally tore her collar off. I just take a little water bottle and spray. I wouldn’t hurt nobody’s animal, but I’m going to protect mine at the same time. FJL31: I have one dog. Her name is Lee-Lou. That in Mandarin Cantonese means perfect. And she is. She was abused as a puppy. It’s actually my brother’s dog but he passed away a year ago and I promised him I would keep her forever. She’s 10 years older than I am and I’m 67 and she’ll healthy as a horse just like I am. We go walk about 6 to 8 times a day. I give her at least a mile to a mile and a quarter every day and I try to get 3 miles myself. CAZ09: I had a dog when I was like 11 or 12 and it got ran over. That really hurt me. [Indiscernible] because I get attached to them. I love them but I can’t get one because something happen to them that’s how I know other people feel about animals when they get hurt. I don’t get none of them. |

| Animals are commodities/products | CGR11: I don’t think people should be able to breed. Certain people, especially if you want to know their background. Some of them be breeding dogs, having them fight. You know, I don’t know. They breed them, fight them. MRJ14: My neighbor has one, and he’s pretty good. Real friendly. And sometimes when they go out of town, we keep him. Pit bull but really trained and loves kids. He’s not no mean dog. He won’t bite unless you try to, you know, go outside, don’t know you, or you try to go in there or something like that. Yeah, really protective. More protection and part of the family. CEK16: Dogs do have litters. They can’t keep all of the litter so they sell the dogs. DWM26: But I was telling [Indiscernible] our daughter bets on dogs but I ain’t never seen it. SRT02: Yeah, it was a business. And were they purebred dogs like they have papers or—I don’t know that much. I know he has a website and that’s his main income in Gainesville. Yeah, I know him and some other guys that do dog shows and stuff like that. I know like some people have those stands or whatever to make dogs breed and stuff like that. But I don’t know. I never went inside and seen his operation. | |

| Animals are pests | MJM17: There’s a lot of dogs and cats around here but the thing about it is when people don’t want to have their dogs around no more they let them run loose. That’s a big deal because basically if you wanted a pet that’s your pet. Not other people’s. Other people trying to take care of your pets that you have that you let loose. A lot of them have owners but the owners let them run loose anytime they want until they want to come home. MOE20: The cats. They just roam. My cats never see outside. But other people, they’ve got the outside cats and they always run around in my yard. JWG09: Barking at 4 in the morning. RCV12: I just don’t like them hanging around because of thieves and stuff. Crapping in the yard. | |

| Acceptance/Pragmatic | MWA22: Just let the, the animal just stay around. They ain’t causing no trouble. Feed off the land. SFF07: If you’re doing it [breeding] for the right reason, yeah, but if you do it for the wrong reason, no. Right reasons to protect your family. If you got paperwork on the dogs and you’re doing it legal, yeah. It’s okay. DWM26: I would buy a dog. I would buy a pit dog. MRJ14: Because betting on it you get caught you’re going to jail. Fighters dog the same thing, going to jail. I’m against that. | |

| Angry/Fearful | CLL12: Hard to answer. I’m like an anti-person. [Indiscernible] I don’t know anyone so... JCL21: Because see I have to stay in my house. When I my house I get in my vehicle and I leave out of here. Come back home and go to my house again. I don’t really—I’m not really from this side of town. I was raised on the Southeast side of town. So that’s where all my family is so when I leave my house—Yeah. I don’t really know what’s going on out here. I have an American Rock and Pit mixed with Jack Russel. They bite. I keep them in my house. [Laughing] JJD30: Because me, I stay in the house. I go in, come out and get grandbabies and go to the grocery store. I stay by myself. MRJ14: Well, over there where I live, I don’t see that. Not where I live at. No. Well, I don’t go on that side. I just keep to myself. | |

| DISPARITIES | Economic insecurity | JFE21: They can’t take care of them. Can’t take care of themselves. MBE12: Same way a lot of people end up over here. The poverty situation. |

| Housing insecurity | EJM18: Yeah. It was the home in Bronson. We had the job situation. Someone stole my car, so I couldn’t get to work. So, the money wasn’t coming in, so they foreclosed and we had to move. We gave the cats to the shelter. JJT19: There is a lot of evictions around here. I own three units here. I don’t allow pets. Yes, we had one tenant who temporarily had his son’s pit bull, and the next thing we knew, there was a whole litter of puppies. They wrecked the whole back fence and chewed holes in the walls. MOE20: Well, what most of the new landlords are doing around here, they are making it pet free. No pits. There’s a pit bull right now—people are moving, and they have got to find a home for it. It’s a five-month-old puppy. They can’t find a place for it. | |

| Transportation challenges | MBE12: Now, I need a vehicle to put myself out of the neighborhood and change this. I have a driver’s license, which is—and I’m 63 though, finding a job, good luck. We just got buses on Sunday. What a God send. Thank you for the little blessing. They feel like they are throwing us a big bone. Look at the bus stops. If it rains, we are still standing in the rain. Go to any other neighborhoods and they have nice covered—don’t get me started. OHM29: Some people maybe don’t bring the pets in for the vaccine. [Indiscernible] I see some dogs. It’s really long trip, painful. | |

| Communication challenges | MRJ14: I don’t have neither one of them [smart phone or internet]. I have a government phone. Just plain phone. SJR16: Yeah, you got my cell number [to call back]. It’s disconnected, unless I pay. | |

| Personal health challenges | DCA08: No. I can’t [work]. I just got—I fell and broke my ribs. I just got out of rehab. That’s why I’m here FJL31: Unfortunately, I was born with congenital cataracts. I’m almost blind in my left eye because it’s hemorrhaged 5 times. MRJ14: I had three jobs. Not now. I’m disabled now. |

References

- Esri. Community Analyst: Reports Reference Guide; ESRI: Redlands, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Patronek, G.J. Mapping and measuring disparities in welfare for cats across neighborhoods in a large us city. Am. J. Vet. Res. 2010, 71, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patronek, G.J. Use of geospatial neighborhood control locations for epidemiological analysis of community-level pet adoption patterns. Am. J. Vet. Res. 2010, 71, 1321–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguilar, G.D.; Farnworth, M.J. Stray cats in Auckland, New Zealand: Discovering geographic information for exploratory spatial analysis. Appl. Geogr. 2012, 34, 230–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, G.S.; Slater, M.R.; Weiss, E. Effects of a geographically-targeted intervention and creative outreach to reduce shelter intake in Portland, Oregon. Open J. Anim. Sci. 2014, 4, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardt, N.S.; Muhamed, S.; Das, R.; Estrella, R.; Roth, J. Neighborhood-level hot spot maps to inform delivery of primary care and allocation of social resources. Perm. J. 2013, 17, 4–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolan, E.D.; Scotto, J.; Slater, M.; Weiss, E. Risk factors for dog relinquishment to a Los Angeles municipal animal shelter. Animals (Basel) 2015, 5, 1311–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss, E.; Slater, M.; Garrison, L.; Drain, N.; Dolan, E.; Scarlett, J.M.; Zawistowski, S.L. Large dog relinquishment to two municipal facilities in New York city and Washington, DC: Identifying targets for intervention. Animals (Basel) 2014, 4, 409–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Searchable Database to Compare Community Lifesaving. Available online: http://www.maddiesfund.org/searchable-database.htm (accessed 20 June 2017).

- Taylor, B.; Francis, K. Qualitative Research in the Health Sciences: Methodologies, Methods and Processes; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz, K. Constructing Grounded Theory; SAGE: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Maps throughout this Article were Created Using ArcGIS® Software by Esri. ArcGIS® and ArcMap™ are the Intellectual Property of Esri and are Used Herein under License. Copyright © Esri. All Rights Reserved. For More Information about Esri® Software. Available online: www.esri.com (accessed on 20 June 2017).

- Florida Geographic Data Library, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida. Available online: http://www.FGDL.org (accessed 20 June 2017).

- Creswell, J.W. Educational Research: Planning, Conducting, and Evaluating Quantitative and Qualitative Research, 4th ed.; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers, 2nd ed.; SAGE: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- X Maps Spot. Available online: http://www.aspcapro.org/resource/saving-lives-research-data/x-maps-spot-gis-program (accessed 4 June 2017).

- Taylor, N.; Signal, T.D. Pet, pest, profit: Isolating differences in attitudes towards the treatment of animals. Anthrozoos 2009, 22, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, J.M.; Carlisle-Frank, P.L. Analysis of programs to reduce overpopulation of companion animals: Do adoption and low-cost spay/neuter programs merely cause substitution of sources? Ecol. Econ. 2007, 62, 740–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kass, P.H.; Johnson, K.L.; Weng, H.Y. Evaluation of animal control measures on pet demographics in Santa Clara County, California, 1993–2006. PeerJ 2013, 1, e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scarlett, J.; Johnston, N. Impact of a subsidized spay neuter clinic on impoundments and euthanasia in a community shelter and on service and complaint calls to animal control. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2012, 15, 53–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, S.C.; Jefferson, E.; Levy, J.K. Impact of publicly sponsored neutering programs on animal population dynamics at animal shelters: The New Hampshire and Austin experiences. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2010, 13, 191–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basic Animal Data Matrix. Available online: https://www.shelteranimalscount.org/docs/default-source/DataResources/sac_basicdatamatrix.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2017).

- Pets by the Numbers: U.S. Pet Ownership, Community Cat and Shelter Population Estimates. Available online: http://www.humanesociety.org/issues/pet_overpopulation/facts/pet_ownership_statistics.html (accessed on 7 March 2017).

- Irvine, L. The problem of unwanted pets: A case study in how institutions think about clients’ needs. Soc. Probl. 2003, 50, 550–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, N. In it for the nonhuman animals: Animal welfare, moral certainty, and disagreements. Soc. Anim. 2004, 12, 317–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographics | Census Data | Interviewees |

|---|---|---|

| Average household size (people) | 3.87 | 2.5 |

| Household income: | ||

| Below poverty line | 34% | 80% |

| Above poverty line | 66% | 3% |

| Unknown | - | 17% |

| Gender: | ||

| Male | 47% | 50% |

| Female | 53% | 50% |

| Education: | ||

| Less than high school | 9% | 29% |

| High school diploma or equivalent | 29% | 34% |

| Some college or higher ed | 62% | 34% |

| Race and ethnicity: | ||

| White | 48% | 22% |

| Black | 45% | 53% |

| Hispanic | 1% | 8% |

| Other/Mixed race | 7% | 8% |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Spencer, T.; Behar-Horenstein, L.; Aufmuth, J.; Hardt, N.; Applebaum, J.W.; Emanuel, A.; Isaza, N. Factors that Influence Intake to One Municipal Animal Control Facility in Florida: A Qualitative Study. Animals 2017, 7, 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani7070048

Spencer T, Behar-Horenstein L, Aufmuth J, Hardt N, Applebaum JW, Emanuel A, Isaza N. Factors that Influence Intake to One Municipal Animal Control Facility in Florida: A Qualitative Study. Animals. 2017; 7(7):48. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani7070048

Chicago/Turabian StyleSpencer, Terry, Linda Behar-Horenstein, Joe Aufmuth, Nancy Hardt, Jennifer W. Applebaum, Amber Emanuel, and Natalie Isaza. 2017. "Factors that Influence Intake to One Municipal Animal Control Facility in Florida: A Qualitative Study" Animals 7, no. 7: 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani7070048