1. Introduction

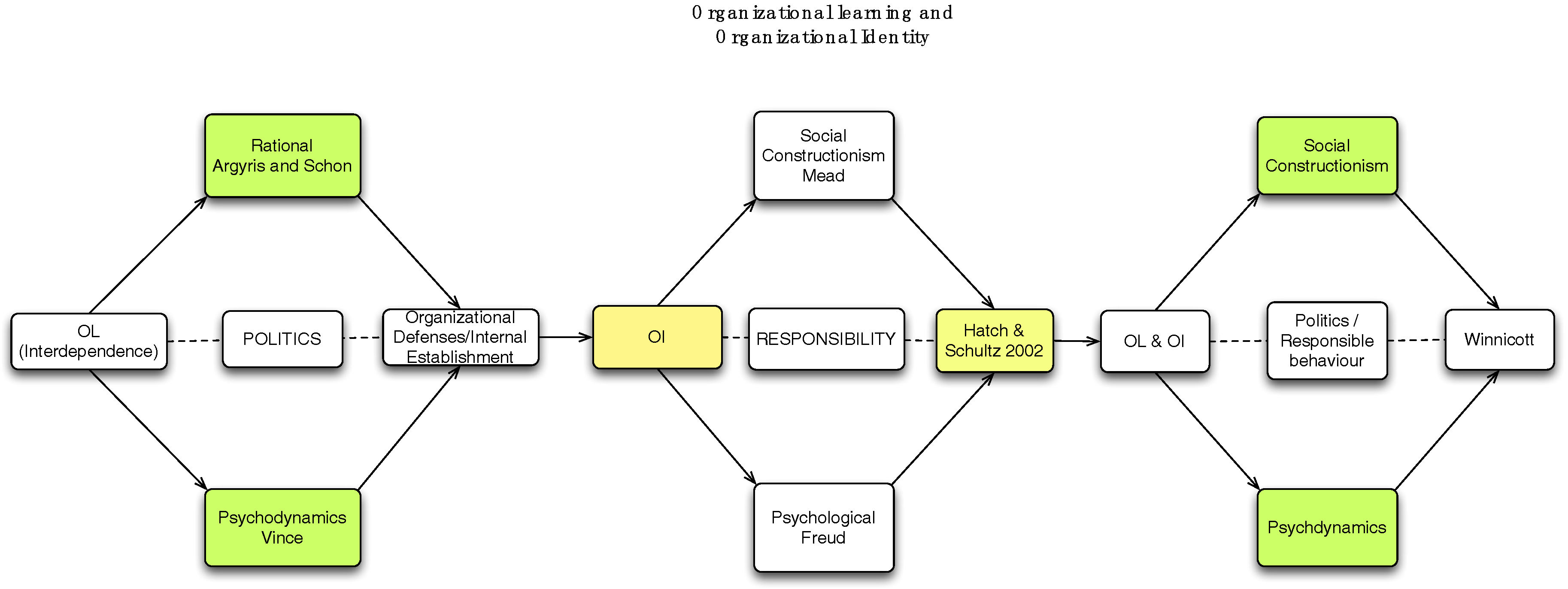

Albert and Whetten (

1985) defined organizational identity (OI) as the central, distinctive and enduring characteristics of an organization. Scholars were fascinated by the construct but found it too complex to apply to organizations. In order to cut through this complexity, over time OI was defined from functionalist, social constructionist, postmodernist and psychodynamic perspectives (

He and Brown 2013). All of these perspectives made great theoretical contributions to the field, but practical application was largely missing. That does not mean that practical work has not been done in the field, but, as compared to the theoretical contribution, it is sparse. Moreover, there also seems to be a lack of integration between theory and practice. In other words, the theoretical side has largely worked independent of the practice side, and vice versa. In this sense, there are very few theories that inform the practice side in ways that are beneficial for actual organizations. However,

Hatch and Schultz’s (

2002) work is an exception in this regard: they provided a theory with a great promise of practical implications for organizations, in regard to continuity and progress.

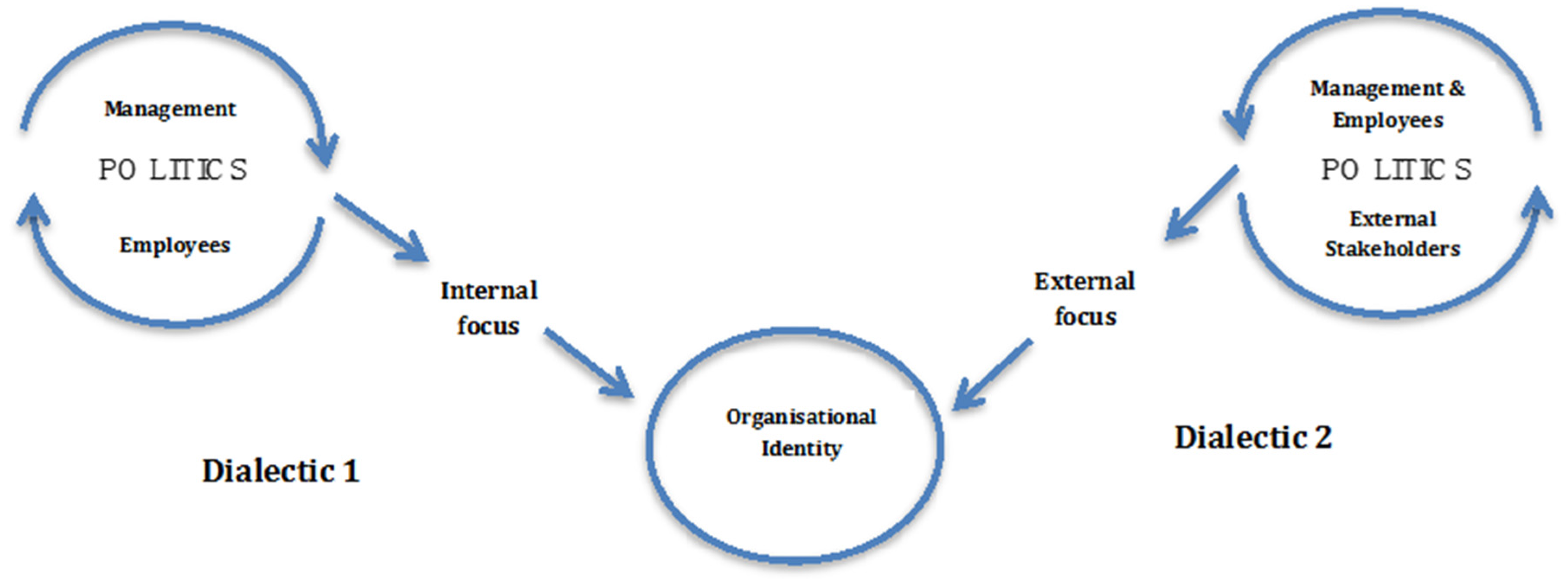

Hatch and Schultz (

2002) defined OI by reference to Mead’s social constructionist framework, which refers to “…the

internal–external dialectic of identification as the process whereby all identities—individual and collective—are constituted” (

Hatch and Schultz 2002, pp. 993–94, quoting Jenkins 1996, p. 20, emphasis in original). They perceived a deeper understanding of OI through a Freudian perspective. From a psychodynamic perspective, they argued that an organization’s excessive internal focus or excessive external focus could lead to organizational dysfunctions, and hence lead to the organization’s failure. They showed that an organization’s health (as manifested in its continuity and progress) depends on the balanced behavior of its members, both among themselves and also with external stakeholders. This balanced behavior is implicit in an organization’s members’ sense of responsibility toward each other and toward external stakeholders.

Hatch and Schultz (

2002) provided an impressive model; however, the present research argues that their model has two issues that need addressing, as follows: (1) They framed their model in a Mead-ian and Freudian perspective, and found it difficult to operationalize. The present research understands that the operationalization issue could be addressed through the relational paradigm of psychodynamics. (2) They did not bring into the equation the fact that responsible behavior is intrinsically linked to individuals’ political interests, which result from unequal power relations both within and outside the organization. The present research observes that this issue of political understanding in

Hatch and Schultz’s (

2002) model can be addressed by reference to certain strands of organizational learning (OL) scholarship.

In OL scholarship it has always been a popular belief among scholars that “…learning inside the organization must be equal to or greater than change outside the organization or the organization will not survive” (

Schwandt and Marquardt 2000, p. 3). OL scholarship has made a tremendous contribution to both theory and practice. However, OL scholarship, by and large, does not link management and employees in a relationship of interdependence (

e.g., Stacey 2003); and it finds politics and emotions to be persistent problems for OL. Nevertheless, noteworthy exceptions to this rule can be seen in the work of

Argyris and Schön (

1974,

1978) and

Vince (

2001,

2002).

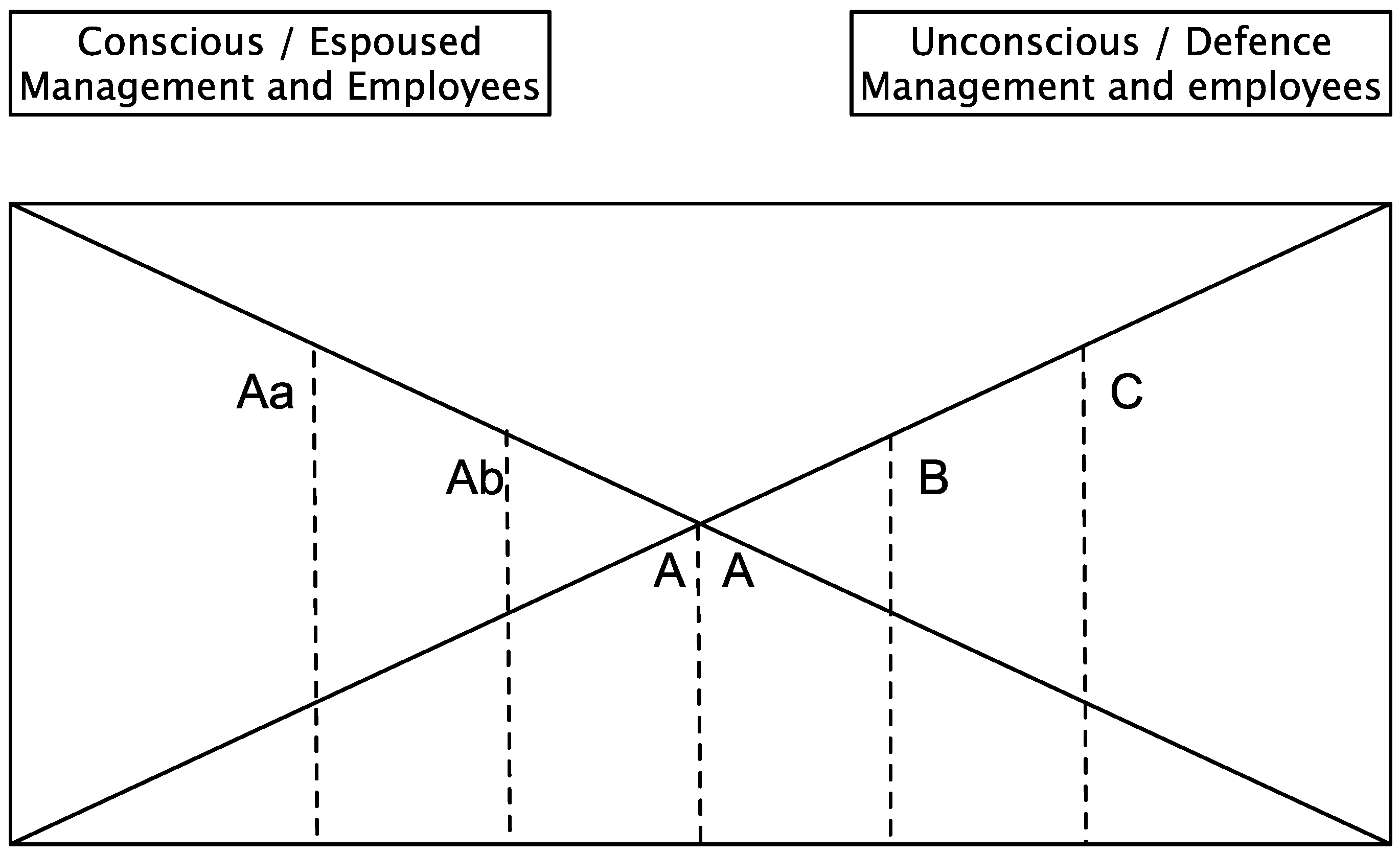

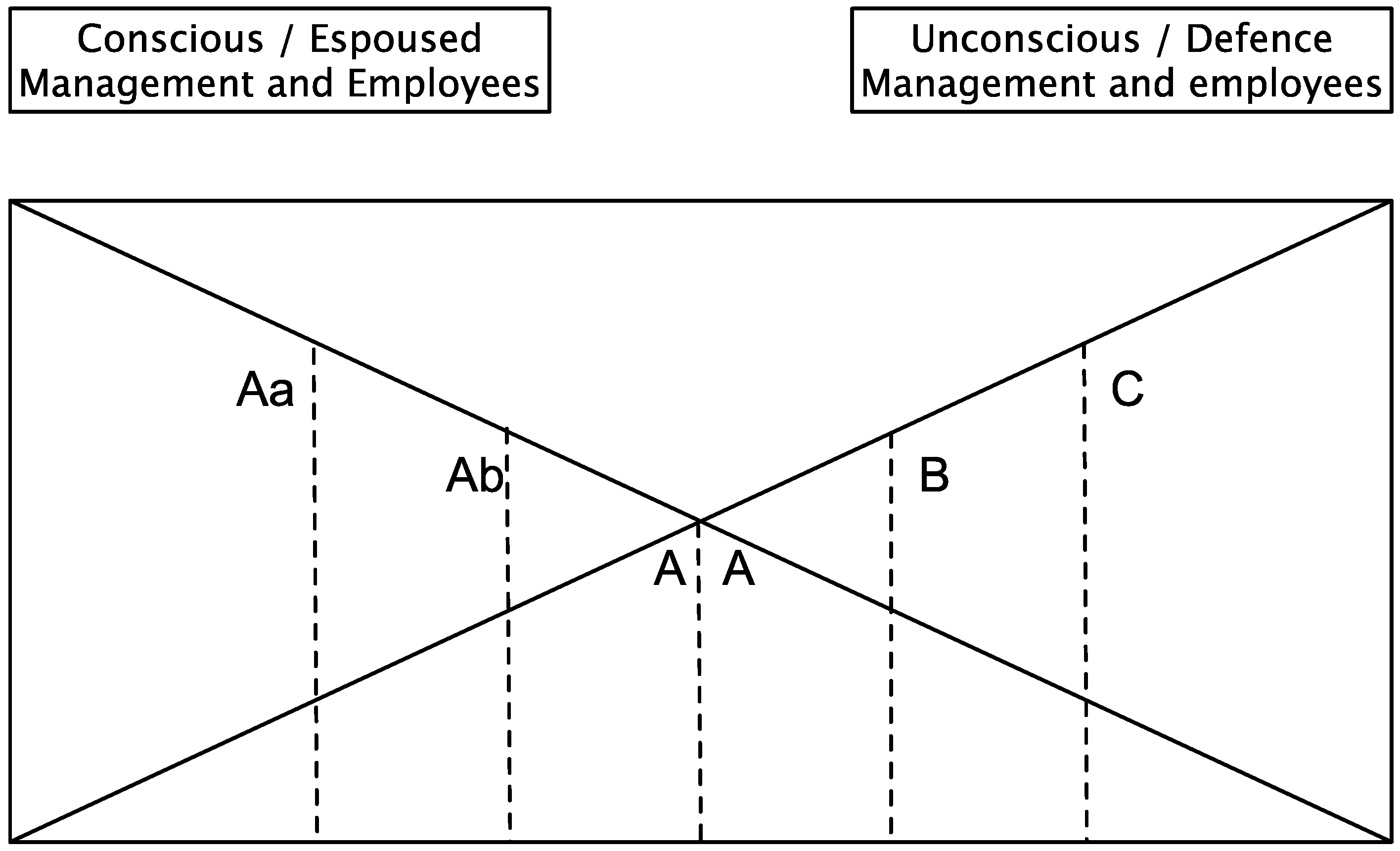

Argyris and Schön contributed to the rational tradition of OL.

Argyris (

1992) argued that an organization’s management and employees, while working in a relationship of interdependence, are linked in a dilemma of “autonomy versus control” whereby both play politics and shape a way of working that is comfortable for both and that is also progressive, i.e., it leads to organization’s continuity. However, over time, this way of working reflects “organizational defensive routines” that are followed by all, unreflectively. In this sense,

Argyris and Schön (

1978) implicitly linked OL to the theory of institutionalization (

Berger and Luckmann 1966) or structuration (

Giddens 1984), whereby individuals shape a structure and are in turn shaped by it. Argyris and Schön did acknowledge the deeper roots of politics, which reside in human psychology. However, they tried to find a solution to organizational defensive routines in individuals’ cognitive potential and, therefore, found it difficult to resolve the issue of psychological politics within organizations. Scholars suggest that any solution to emotions need to be understood in psychodynamics (

e.g., Diamond 1986;

Antonacoupolou and Gabriel 2001).

In regard to psychodynamics,

Vince (

2001,

2002) argued that management and employees are linked in an unequal power relationship in relatedness, and that this makes OL a political process. Management and employees mitigate politics by forming an “internal establishment” (

Hoggett 1992) that creates familiarity and ensures both management and employees work together to achieve the organizational goals. However, this internal establishment also reflects a way of working that, over time, becomes institutionalized in organizational systems, policies, strategy and so on. In this sense, Vince also implicitly perceived the formation of “internal establishment” as involving agency and structure dialectics, whereby individuals form a social structure and are in turn formed by it. Thus, “organizational defensive routines” and “internal establishment” represent one and the same thing: both are political structures and both reflect the deeper roots of politics, which lie in human psychology.

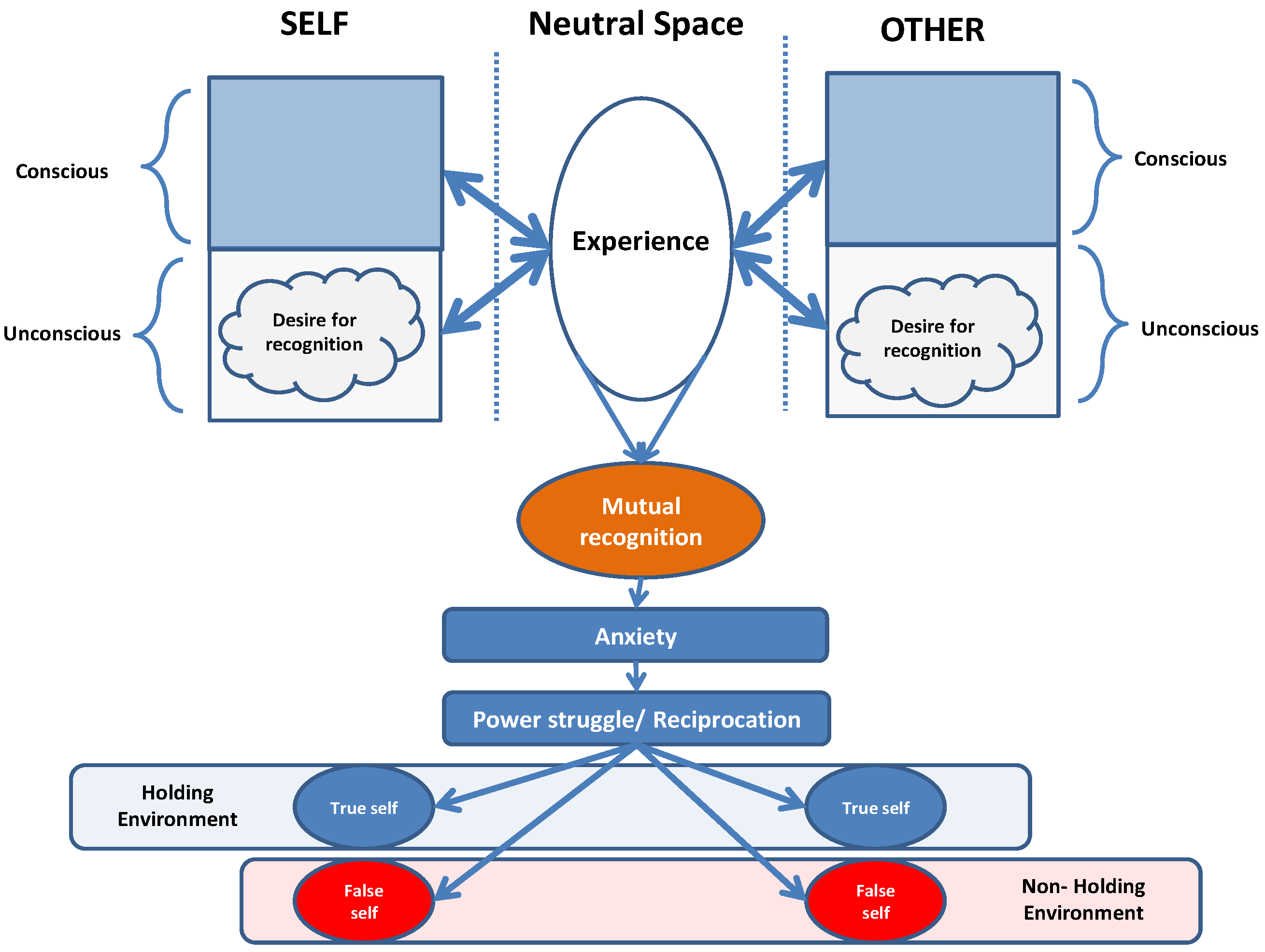

Dialectics, in the psychological understanding, links management and employees in a ‘dilemma of mutual recognition’ (

Benjamin 1990). Mutual recognition, in Hegelian dialectics (

Hegel 1807), depicts two essential but conflicting positions: management wants to work according to their own logic and employees want to work according to their own logic. This instigates a psychological politics between the two: ‘I refuse to recognize you unless you recognize me’ (

Benjamin 1988, p. 38).

The politics that is played out between these two actors is not aimed at defeating the other but at “…maintaining a state of continuous difference and provocation” (

Cooper and Burrell 1988, p. 99): i.e., “…if we fully negate the other, that is, if we assume complete control over him and destroy his identity and will, then we have negated ourselves as well. For then there is no one there to recognize us, no one there for us to desire” (

Benjamin 1988, p. 39). Within organizations, management and employees mitigate psychological politics by shaping a way of working that is comfortable and progressive. Over time, this way of working becomes the commonsense reality. In OL scholarship, Argyris and Schön identified this commonsense reality as “organizational defensive routines”, and Vince identified it as an “internal establishment”. Since politics arises from the distinctive identities of the management and the employees, in the dialectical interplay it seems that “organizational defensive routines” or the “internal establishment” reflect OI: that is, it is “the way we do things here”.

The above discussion shows that scholarship in the field of both OL and OI appreciates that, in a psychological sense, OI is constructed in a dialectical tension. OI scholarship frames dialectics in the responsible/balanced behavior of individuals that lead to organization’s progress and continuity. OL scholarship frames dialectics in the political behavior of individuals that stand in the way of an organization’s progress and continuity. From a psychological perspective, it seems that political and responsible behavior, which are the dialectical outcomes of unequal relationship, reflect two sides of the same coin. This shows that OL and OI are intrinsically linked and could benefit from being viewed through the relational paradigm of psychodynamics.

The relational paradigm ‘departs from instinctual models of motivation to relational model; where importance is placed on the role of personal agency, conscious motives, relational experience, and social involvement in conceptions of personality development’ (

Borden 2000, p. 356). There is no dearth of scholars who have made valuable contributions to our understanding of the relational paradigm of psychodynamics. One such scholar is Winnicott. Since OL and OI are intrinsically linked the present research uses the Winnicottian model, as Winnicott also sees individual identity as being intrinsically linked with the individual potential of learning. Moreover, Winnicott perceives the process of individual identity construction as involving Hegelian dialectic, and his work in dialectical framing has a social application. Lastly, Winnicott sees responsible/balanced behavior as taking place in a “holding environment” of trust and understanding. The present research, hence, seeks to operationalize

Hatch and Schultz’s (

2002) model through applying a Winnicottian understanding, by seeing how OI is socially constructed and psychologically understood through the political interests of the management and employees, among themselves and with key external stakeholders. In doing so it explores the political implications of OI for OL, as perceived in an organization’s continuity and progress. The following sections discuss OL, OI, power scholarship, the Winnicott model and the conceptual framework. This is followed by a discussion of the context of the Pakistani police, the research methodology, an analysis of the data, discussion, and an assessment of the contributions and the limitations of the research.

4. Context of the Research

This research was conducted in the context of the Pakistani Police. However, before explaining this context, the present research first of all introduces policing in the pre-colonial, colonial and post-colonial periods. In pre-colonial times, the Mughals exercised their authority in civil matters through an elaborate system of policing. While a basic informal system operated in villages, cities had more elaborate structures, where Kotwals (city police officers), not only maintained law and order and controlled crime but also dealt with all sorts of administrative and regulatory functions, like checking weights and measures, regulating the movement of people into and out of cities, and other civic functions. The Mughal system placed a heavy responsibility on Kotwals: for instance, in the case of non-detection of stolen property, they would face the penalty of paying compensation to the victim. In practice, this was a rare occurrence, as a Kotwal using his unchecked powers could coerce the victim into silence and a retraction of the complaint. The relationship between a Kotwal and his subordinates was strictly hierarchical and the treatment of citizens was not strictly rule based, with citizens often the victim of Kotwal unchecked powers. The effectiveness of enforcement was variable between districts. The concept of the rule of law was weak and the only factor in determining the quality of policing was fear of the king, with all of the physical limitations this implies.

With the British takeover of the subcontinent from the East India Company after the revolt of 1857, a formal policing system was established under the Police Act 1861. This laid the foundations of modern policing in the subcontinent. Police powers were defined under a legal framework and the hitherto unchecked police powers were placed under the supervisory control of a civilian District Magistrate (DM), who also exercised basic judicial functions and tried minor crimes, in addition to his role as general administrator of the district. The police, under a Superintendent of Police (SP), were responsible for crime control and also assisted the DM in the maintenance of general law and order. This largely introduced the rule of law, with criminal matters ending up in, and being decided in, a formal system of courts that dispensed criminal and civil justice. However, in matters that were of interest to the British Raj, the police acted as an instrument of the perpetuation of British colonial rule. The key features of the British police system were, (i) a duality of control whereby in addition to the SP’s operational control over police, the DM also exercised somewhat intrusive control over their operational matters, and held them to account for their performance; and (ii) the concentration of authority in the police hierarchy, whereby from the Station House Officer (SHO) to the SP, all functions, like watch and ward, traffic and investigation were exercised by the same individuals.

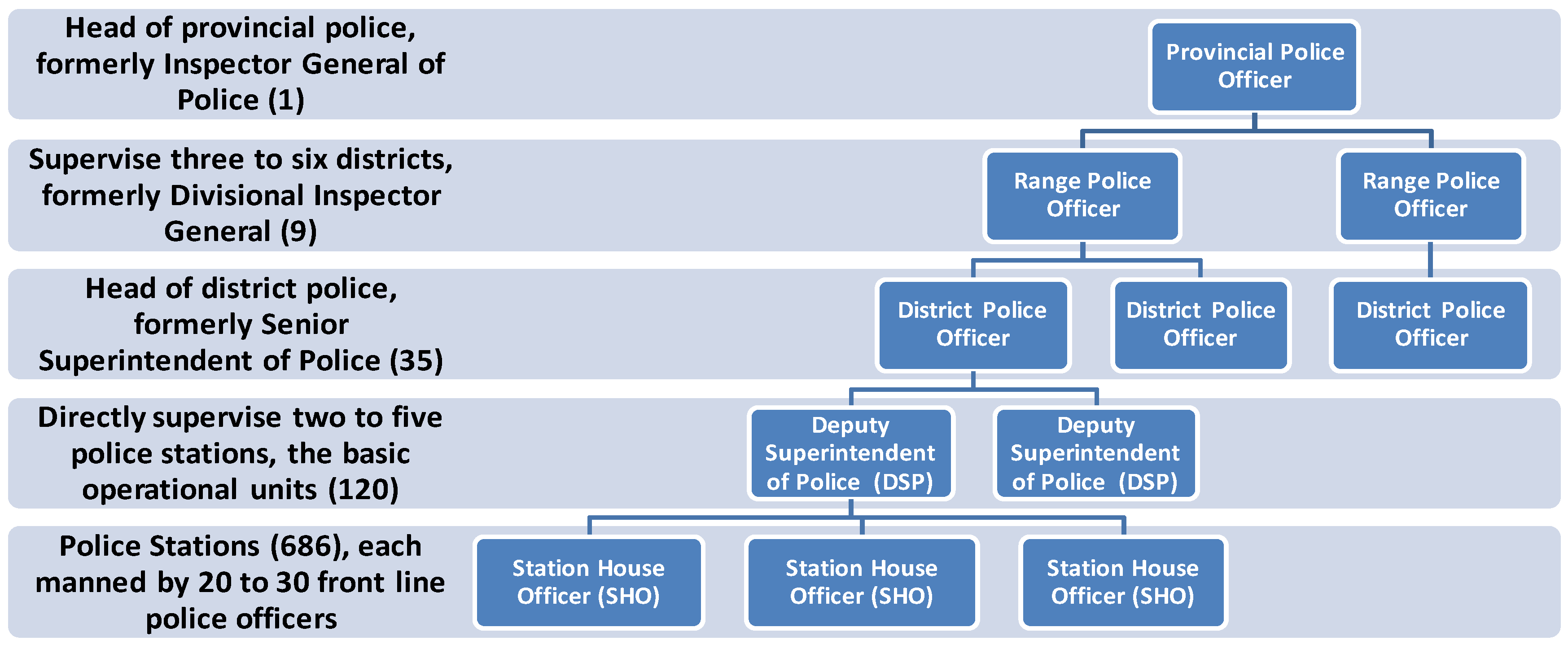

The post-colonial policing did not differ much from the colonial period, especially in terms of the operating laws and rules. The internal organizational hierarchy and the external relationships remained unchanged. The key changes, observed over a period of time, were a decline in the quality of policing and discipline, and an increase in corruption. A key departure from the pre-colonial tradition was a steep jump in political interference and the influence of feudal elites in the affairs of the police. With the passage of time, the citizens’ trust in the police was significantly eroded, and the performance of the police sharply declined. All of this happened in tandem with an erosion in the performance of other institutions of the state. The relationship between the SP and the DM continued, albeit somewhat strained, with the DM retaining the overall—but gradually declining—primacy. The current structure of the Pakistani police is given in

Figure 5 below. It also indicates the former structure: Inspector General (IG) is now called Provincial Police Officer (PPO); Deputy Inspector General (DIG), is now the Range Police Officer (RPO); and Superintendent of Police (SP) is now the District Police Officer (DPO). Apart from the change in nomenclature, there has been no change in hierarchy or their responsibilities.

In 2002 the military government introduced reforms of the police, under the Police Order 2002. The Police Order 2002 aimed to reform the police force: the thrust of the Police Order 2002 was to create a people-friendly police force that was more aligned with the democratic needs of the country. Efforts to change the old model, as defined in the Police Act of 1861, had started soon after the partition, or the independence of Pakistan, from 1947 onwards. However, the political platform for making real change was finally provided in 2002 by the advent of army rule: the army wanted to legitimize its rule by showing democratic shades, through various reforms. The Police Order 2002 was one of these reforms. The main agenda of the Police Order 2002 was to abolish the office of the DM as holding a dual control with the police, by shifting the accountability of the police from the DM’s office to the Public Safety Commission (PSC), which comprises retired or in-service honorable members of the society. This involved introducing specialization in the operating level, by separating the police’s function of watch and ward from that of investigation. The main aim was to make the system fair, and also to make crime control and investigation services more effective.

5. Data Collection

The present research is based on an interpretive paradigm and operationalizes OI in a social constructionist framework. Its application of power is informed by a Foucauldian perspective, as seen in the discursive and non-discursive practices of the Pakistani police. The deeper meanings are deciphered in the Winnicottian framework of psychodynamics, as perceived in a dilemma of mutual recognition. The present research uses narratives to connect the social constructionist and psychodynamic perspectives. For the research, 25 semi-structured narrative interviews were conducted: 15 with police officials and 10 with key external stakeholders. The police force interviews were conducted during a tense period during which the police were the main targets of terrorist attacks. Therefore the interview venue often changed and the interviews were sometimes rescheduled. I carried out eight interviews with the senior police management and seven with the operational tiers. The external stakeholders consisted of five DMs, two legal professionals, one development consultant and two ordinary citizens. The interviews lasted for 45 to 60 minutes. The interviews were recorded by taking consent from the interviewees. Eight interviews were conducted using Skype and the rest were carried out face to face in police stations, senior management offices, and government rest houses. Due to the tense situation within the country and the very busy schedules of both police officers and DMs the samples were selected through network connections, depending on who was available at the time.

The interviews were open-ended and probing questions were asked when necessary. The focus of the questions was on “how” and not on “why”, as why questions imply a value judgment and put the interviewee in an uncomfortable position. Moreover, for a psychodynamics study “why” questions would make analysis difficult as this may raise the interviewee’s defenses and hence block meanings and open interactions. The main questions stayed around the theme of reforms, trying to understand the reasons behind the reforms and also trying to decipher the reason for their failure. “A narrative, in its most basic form, requires at least three elements: an original state of affairs, an action or an event, and the consequent state of affairs” (

Czarniawska 1998, p. 2).

The interviews were conducted in three main languages: Pushto, Urdu and English. Pushto and Urdu interviews were first translated and then transcribed. In transcriptions attention was paid to the smallest details, like the sound of a person coughing or a lowering of the voice, in order to record the emotions that are the main framework of the present study. The research was supplemented by the observational method of maintaining a reflexive diary, as well as by relevant secondary sources. Observing and reflecting is second nature to human beings. Reflexivity kept me engaged with the feeling of “doubt’” (

Locke et al. 2008), which made me engage in critical self-reflection by exploring my own interpretations of empirical material (

e.g., Alvesson and Skoldberg 2000). I observed that my network connection often initially put the lower tiers in an uncomfortable position, and I found that building trust between the interviewer and interviewee was key to getting a valid and reliable account of the events being studied.

The reflexive diary also helped me make notes of the various discursive and non-discursive practices of the police. For example, I noted the difference between the luxurious air-conditioned offices of the senior management and the open verandas where the public have to wait to see the senior officers on hot summer days. This made me reflect on how the management espoused a form of friendly policing, but they were not concerned about the conditions that the public faced in meeting them. The luxurious offices of the officers showed the police’s non-discursive practices, which seemed to follow the setup of the colonial times. This led me to consider the question: was the colonial system of policing really as uncomfortable for the police as the senior management suggested it was throughout the interviews?

The secondary data consisted of organization reports, international donor reports, Transparency International reports, crime statistics, minutes of meetings, press releases, websites that I visited, media reporting that I followed, and archival data, as well as reports from bilateral and multilateral development agencies and rights groups.

6. Data Analysis

The objective of analyzing data is to produce a coherent, intelligible and valid account (

Dey 1993). The analysis requires breaking the data into smaller bits so that the data can be classified. However, there is no set of rules or specific recipe for analyzing data that will provide the best results (

Boulton and Hamersley 2006). Qualitative data requires a degree of interpretation and creativity, which can account for why different researchers produce different analyses for the same data (ibid). Hence, qualitative data collection and analysis is often considered more subjective than the analysis of quantitative data (

Neuman 2011). However,

Kirk and Miller (

1986) argue that qualitative social science research can still be evaluated in terms of its objectivity, by way of the reliability and validity of its observations.

I received help from a colleague who worked on the data independently. It was encouraging to me that he saw similar themes to those I identified, although his labelling was different. Group data in itself brings some authenticity through the common voices of the group; e.g., common management themes were their aspirations, and the problems that came in their ways; and for employees it was predominantly the practical difficulties encountered in adopting these reforms. However, the exercise is not straightforward and is also not done in one go. Rather, the analysis involves reading and re-reading transcripts, repeatedly listening to audio recordings, grouping or clustering the data for interpretation and to identify relationships, and questioning, checking and verifying transcripts to ensure the validity of findings (

Janesick 1994). I also started the initial phase of the data analysis by listening to the recordings while checking the accuracy of the transcripts. This gave me the opportunity to re-familiarize myself with the data and to go through the field-notes that I made during the interviews.

The data was analyzed using

Riessman’s (

2008) narrative methodology. Narrative methods were specifically selected to engage with the emotions of the police officials, especially as seen in the unequal structure of the social setup both within and outside the organization. In this way the present research used all three of Riessman’s narrative analysis techniques: i.e., content, context and performance. Content techniques focus on what is said and help decode themes in a general understanding, without going into context. However, the narrative is always articulated in a context that brings dialectic to the center, whereby individual talks of both the personal and collective (institutional) discourse (

Ybema et al. 2009). Dialectics bring to the center the political nature of the narratives: i.e., “It is impossible to understand human conduct by ignoring its intentions, and it is impossible to understand human intentions by ignoring the settings in which they make sense” (

Czarniawska 1998, p. 4;

quoting, Schütz 1973). Thus, in an unequal distribution of power, politics are central to narratives, and narratives are underpinned in emotions. In this sense, the performance analysis helps understand the narrative in its deeper emotions, as seen in stresses, repeated words, and what is said and not said. The “… dialogic/performative approach asks “who” an utterance may be directed to, “when,” and “why,” that is, for what purposes?” (

Riessman 2008, p. 105).

To start the analysis of the interviews the questions were first removed to help improve the understanding of the narratives. Since the questions were open-ended, with probing questions added in between, by removing the questions the narratives appeared in a continuous way. In this sense, attention was paid to “… the whole data and paying attention to links and contradictions within that whole” (

Hollway and Jefferson 2000, p. 5). By this the present research means that the social and psychological context were focused together, by looking at the stresses, repeated words, justifications, rationalizations, projections onto others to see how narratives expressed the self-interests of the narrator/interviewee. The present research did not utilize any software, as the focus was on the psychological dimension of politics. In a psychological sense, it is possible that the same words might not provide the same meanings each time they are used, and the researcher needs “to do justice to the complexity of [their] subjects” (

Hollway and Jefferson 2000, p. 3).

The research’s prime focus was the police; therefore, police narratives were used as the main framework to identify the patterns and relationships, in order to locate the issues in the reform agenda. The DMs and legal professionals’ interviews were used to understand the issues identified by the police, as these individuals work in parallel with the police. However, here also, patterns were located to understand the words, stresses and linkages in which they gauged the issues that were identified in the police narratives. The other external stakeholders were generally asked questions about the police’s image, to understand the police and community interface. In this way, the present research engaged with the data relating to the police.

Initially, the data was loosely categorized into as many clusters as was necessary, and only when this was achieved were the clusters with similar ideas grouped together. The clusters were formed based on the use of repeated words, which brought three broad themes into focus: police history, police performance and police autonomy/power vis á vis the other. The process of identifying the broad themes seemed to be aligned with the Riessman content analysis, which allowed me to understand “what was told” and not “how it was told”. The telling part required Riessman’s context analysis.

For context analysis, a spreadsheet was prepared and the broad themes were put at the top. The name and role of each police official (management and employees) was put on the side, to understand how they perceived these three broad themes in the wider social context. While understanding police narratives in the social context, the “self /other” perspective came to the center, where the interviewees would narrate the stories conveying the meanings beneficial to the self (

e.g., Riessman 2008;

Bruner 1991). The stories capture “self /other” talk in the politics played out in the blame games. The political games were seen in rationalizations, projections on others, justifications and at times frustrations of the interviewees on the current political situation of the country. The narratives of the police management and employees were somewhat similar in the blame games but essentially both had two different focuses. Police management interviewee (PMI) narratives were evaluated with respect to the PMIs’ aspirations: they blamed the “others” throughout their interviews in order to rationalize a need for change/reforms. This ‘blame game’ started in the historic period and extended to all those who stood in the police’s way in regard to developing an effective police system for Pakistan. The employees’ narratives were based on the practical side of their jobs: they blamed “others” to show how inappropriate the reforms were, from a practical point of view.

Politics, as seen in these blame games, were loaded with emotions, for example involving anger, stresses and repeated words in relation to the “others”.

Riessman (

2008) argues that the order of an analysis is not important. Therefore, I merged performance with the context, and thus disregarded the order, to better understand who the significant “other” was that was blamed the most. In this sense, to understand the context of the present research, the data was understood by reference to the social constructionist and psychodynamic frameworks. The social constructionist and psychodynamic frameworks stress the “need to posit research subjects whose inner worlds cannot be understood without knowledge of their experiences in the world, and whose experiences of the world cannot be understood without knowledge of the way in which their inner worlds allow them to experience the outer world” (

Hollway and Jefferson 2000, p. 4).

In the performative analysis, the meanings were gauged in the way police officials emotionally framed the significant ‘other’ in the blame game. The PMI narratives showed that the reforms agenda was predicated on their need for “autonomy” and employees’ narratives showed that the reforms were seen as an attack on their “autonomy”. This allowed me to see that the reforms were articulated in the overarching theme of “autonomy versus control”, with reference to the significant “others”. However, the police management interviews made it difficult to locate the significant other, as PMIs were not direct in their accusations and blame. It was their stresses, concealment games and what was not said that led me to believe that their aspiration was independence from the DMs, to strengthen their control over employees and to make the police an effective organization for Pakistan. The employees, on the other hand, were loud, clear and accusatory in their blame game, and tones of anger were used. For them, the significant other was the community, which they perceived wished to take away their autonomy (through citizen oversight bodies).

The interplay of autonomy versus control brought to the surface the politics between the two. This showed that the PMIs were embroiled in psychological politics in a dilemma of mutual recognition with the DMs; and the employees on their part were engaged in a dilemma of mutual recognition with the community. In my research, four themes appeared to stand out, each with its own explanation in a dilemma of mutual recognition: (1) the repressive origins of policing, (2) the duality of control, (3) the police oversight and (4) the forgotten (operational-level) employees. I sum up the analysis of the interviews with Pakistani police in

Table 1 below.

6.1. The Repressive Origins

The theme of the historic period was central to all the interviews that were conducted with the police. The Pakistani PMIs made the colonial police system the premise for introducing reforms in 2002, with the stated aim being to improve police performance. However, my deeper analysis shows that the seductiveness of power continued, whereby the PMIs actively supported the efforts to abolish the oversight and control of the DMs. The operating level of the police, on the other hand, seemed to carry the historic narrative forward as a ritual, as they had no problems with the British Act of 1861: in fact, they were the beneficiaries of the Act, under which the SHO enjoyed unlimited powers.

In colonial times, the British/Europeans held the positions of DMs and Superintendent of Police (SPs): the natives only worked at the operating levels, as constables, inspectors and so on. One of the DMs, in an interview, revealed that a few letters were found in archival documents that showed a very strong tussle between the DMs and the SPs even in the colonial times: i.e., among the British/Europeans.

India and Pakistan both inherited the British system of police and while doing my research I also came across a news story on the tussle between the Indian DMs and SPs, which was widely circulated in Indian newspapers. The gist of the news story was captured in the following words: “‘It all began after SP Mohit Gupta ordered transfer of a few police station in-charges, replacing them with other officers at some of the police stations in Sidharthnagar. As per the practice, the SP office issued the transfer posting orders and dispatched a copy to the DM office for information sake,’ said the source. ‘Things began to turn ugly when the DM took strong exception to the orders of the SP “without her prior approval”. As a result, the DM not only cancelled the orders issued by the SP but went ahead to announce that no police officer would be posted as the police station in-charge unless and until he is interviewed by her to decide if he was capable of shouldering the responsibility’” (

Siddiqui 2012). This shows that politics were intrinsic in the dual control of the DMs/DPOs, which finally resulted in the termination of the DM’s role in the affairs of the police in Pakistan. In a narrative analysis, the politics could be detected in the ways the PMIs made the Police Act 1861 an excuse to remove the dual position that they had held with the DMs for more than a century. PMI 1.2 said: “The Police Act 1861 and the Police Rules of 1934 were used to subjugate the masses…it was these rules that adversely affected our performance.”

However, in the narratives of the PMIs resentment was visible in regard to the dual control with DMs. PMI 1.1 said: “The responsibility for law and order was primarily with the DM, who was the head of the district, head of the revenue and head of the police...he was a sort of mini-governor…the DM headed 40 different functions and his connection with the police was only because of his being DM”. This interview captures the PMI’s emotional stresses in words like “mini-governor” and “40 different functions”, and shows that the main problem for PMIs was not the outdated British model, but the dual control with the DMs: the PMIs felt frustrated that the DMs had a higher status in terms of power and image within the society, compared to the police.

This psychological politics seems to have motivated the top leadership of the police to fully support the reforms initiated by the military government, without necessarily mirroring any public demand. PMI 1.3 said: “These [three senior police officers] were the three main architects, as far as I know, of this entire law. They did consult police. I am not sure whether that consultation was very...uh...deep in its nature”. This point seemed important as I noticed a similar debate on an Indian TV program, where the anchor person asked a senior police officer the following question: ‘as police leadership you know the internal issues; why don’t you bring about change?’ The senior police officer conceded: “Why would we, who are in power, change the system as we are its biggest beneficiaries? Change has to come from outside; it has to be in response to public demand” (

Khan 2012). Interestingly, the senior management of the Pakistani police got an opportunity to shape the reform and they actually used it in their favor. DMs historically were a bone of contention for the police management, and in the case of the Pakistani police this became the main reason for the overwhelming support of senior police management for introducing the reforms of 2002, which largely focused on doing away with the control of the DMs over the police.

6.2. The Dual Control

As discussed above the PMIs targeted the Police Act 1861 that introduced the concept of a dual position with the DMs. The DMs were, therefore, the sore spot, to which senior police never referred directly, and which I captured by identifying the emotions that came to the surface—they never uttered a single word against the DMs: in the interviews they exhibited concealment, avoidance, and uncomfortable twisting in the chair, or saying with visible under-confidence, “you know the DMs used to work with us”. These games were revealed in various tones and stresses that showed their psychological politics with the DMs. This led me think of the DMs in the PMIs’ interviews as the “invisible intruders.”

In games of concealment the PMIs blamed everything on historic times, not once quoting specific examples of what happened in the present time that made the police relationship uncomfortable with the DMs. For example, PMI 1.1 stated: “the DM would tell the police to ‘catch him and bring him, lock him up for this long’ or ‘thrash him’ and the police officers working under him would do it. There was no [internal] accountability [to senior police], rather a lot of confusion, and shifting of blame”. PM1.1 was never direct in referring to modern DM intrusion, instead making reference to the historic period. He never gave any example to show that such practices took place in the present time.

To check the practices involving DMs and the police, from a DM’s perspective, I refer to the interviews with DMs. DM 3.2 stated: “...[The] Deputy Commissioner (DC/DM) had been given quite a lot of powers, as prescribed in the law, but they were not exercising those. For example, the Law of 1861 required that the SP would seek the DC’s [DM’s] approval for the transfer of a SHO. I cannot recall even a single incident where this was being done. The police were fairly independent in their decision-making...So I don’t think the issue of autonomy was there, or [that] they were [under] control of the executive magistrates”.

The DM’s reference to autonomy clearly shows the dilemma of mutual recognition between the police management and DMs. In his interview, the DM insisted that they never interfered in regular police practices. They were two independent groups serving the community. The DM in the interview clarified further that, as district heads, they made the police accountable for their performance in the district and also took decisions at difficult times; otherwise, both worked independently. DMs were required to use their coercive power in a legal functional capacity during the exercise of their judicial authority, the exercise of which was also subject to subsequent judicial review in higher courts. Since the DMs and police routinely worked in two different organizations, there was no chance for the DMs to exercise any dominating power that would shape the thoughts of police employees or the police culture. On the other hand, however, according to one DM, the magistracy provided a buffer for the operational-level police in their encounters with a protesting public, and had an overall tempering effect on crowd emotions, due to their perceived neutrality—or the fact that they were seen as not being part of the police.

However, on deeper reflection, DMs were not as ‘clean’ as they appeared to be and their open criticism of the police showed their sense of superiority over the police, which they otherwise denied. Rather, they tried to convince me (the interviewer) that they were friends and colleagues. For example, while defending the DMs’ position vis à vis the police, DM 3.5 showed this attitude in the following words: “...There were, theoretically speaking, a number of powers that if we used, we would have kept the police indefinitely accountable”. This statement captured the DMs’ antagonism toward the police: they would tend to exaggerate their powers to show that the DM was the boss. However, when I checked the DM–police relationship by investigating other sources, I found that in reality the police and DMs worked on a par with each other and DMs only exercised limited powers vis à vis the police. However, a power asymmetry was visible in the ways the DMs were so conscious about this power. DM 3.1, while talking of his time in a district, laughingly revealed his treatment of the SP in the following words: “we had to ask about their performance and the SP used to feel quite embarrassed to talk before the juniors, so they tried to turn their back toward them or push the chair in front as if they were working in parallel with us.” This showed that the DMs even used their power advantage in psychological terms, and it seems that over a period of time this must have angered the SPs. There are reverse examples also, where a DM (3.4) said that to mitigate this psychological imbalance: “I always asked the DPO to sit on the front seat and I would drive the car myself to give a feeling of comfort to him and let the public see a harmony between us”.

In the British period, the power asymmetry was further accentuated through non-discursive practices: the DMs were given much bigger bungalows than the SPs, and were allowed to raise a British flag in their house, as representatives of the British government. These practices continued into present-day Pakistan and widened the psychological divide between “us” and “them”. A psychological divide is the strongest basis for politics when there is a situation of power inequality. “The active individual is fully involved when it comes to realizing power relations in practice. The individual thinks, plans, constructs, interacts and fabricates. The individual also faces the problem of having to prevail, to assert himself, to find his place in society” (

Jäger and Maier 2009, p. 38).

The police were desperately looking for an opportunity to get rid of the DMs’ role in relation to their job, to appear equal with them in the eyes of the society. This psychological politics led to overwhelming police support for the abolishment of the DMs’ dual control with the police: incidentally this was the only provision of the 2002 reforms that was adopted and implemented in full.

6.3. The Police Oversight

The direct implication of abolishing the role of the DMs was the need to replace the oversight of the police with another system. The architects of the reforms selected a group of people that senior police management maintained were respectable citizens of Pakistan, which mostly consisted of retired officials. This body was named the PSC. The senior management of the police argued that this was the model used by many modern societies and they borrowed the idea from Japan. Since Pakistan aspired to become a modern country, it also needed to develop like any modern country. The PSCs, however, were unable to function in reality.

The irony of the situation was seen in the ways the PMIs themselves conceded their superiority over the community—while at the same time claiming they wanted the community’s oversight over themselves. PMI 1.4 said: “I regularly hold ‘darbars’ [where a public congregation is addressed by the leader] where I encourage the public that we are there to serve them. I encourage them in their rights to come and [help us] fight against crime.” This shows that the PMIs’ apparent support for the concept of PSC was a form of lip-service. DMs were worried that the police were playing a game—with the aim of giving themselves unchecked power. One of the DMs (3.1) said: “I remember watching the news in 2003 and saw the police dragging a man, hand-cuffed, who was shouting that he was (a head or) a member of PSC.” This showed that the police management wanted to get rid of the DMs, and wanted no effective control to oversee their performance. One of the external stakeholders (ES) 4.3 captured this in the following words: “At this point, it is very difficult for any community leader or member of the community to try and think to work with the police, there is practically no trust between the two”.

6.4. The Forgotten Employees

To improve police effectiveness, the reforms included a clause on the separation of the watch and ward function from the investigation function; this required the operational tiers of the police to let go of their previous identity, which was associated with power and control over the community. However, PMIs were fully aware that the lower tiers were used to abusing the power that they historically held and that it would be difficult to make them change their identity as figures of power. PMI 1.5 conceded: “But are we ready at the operational level to have that kind of change, where your SHO is the end-all…he is the symbol of government authority in a police station’s jurisdiction. How can you immediately take away a substantial part of his work and authority from him and expect the police not to react to it?” However, PMIs insisted that the change was possible through tighter control, and that this meant getting independence from the DMs first and then making sure that the junior level of police obeyed them, without any intrusion in between. However, this did not result in a change of identity for the lower tiers, or for the organization.

The lower police tiers considered the reason for the failure of the reforms to be the lack of communication between the management and employees. Employee 2.1 said: “We live in a feudal society where an SHO cannot survive without satisfying the feudal lord…it is a political game that our seniors are aware of and remain quiet [about]”. Employee 2.2 said: “We are used by the political leadership and also by the seniors. We are supposed to work as specialists, but how can we?...One moment we are investigating a case, the next moment an order comes to control the mob on the street”. Employee 2.3 said: “We put a person behind bars and the next day our senior wants us to release him, it is not only frustrating but gives the advantage to other criminals and exposes the society to danger”.

The PMIs knew that internal change was needed, as ordinary citizens feared the police. One external stakeholder (ES), 4.3, said: “Violence is almost endemic in police stations, the way the police operate, whether it is for investigation, whether it is for law and order; that fear is there, the weaker the person the harsher the violence and torture becomes”. In regard to such a scenario the PMIs only provided defenses and rationalization as the lower tiers’ behavior also reflected on the management’s lack of ability to control them. For example, regarding the issue of monetary corruption PMI 1.4 said: “The police symbolize the state, if the Customs department doesn’t fulfill their duties, they are not criticized as badly as us and the [same] volume of corruption is seen in Departments of Health, Education, Taxes, Customs, but we are always criticized.” On other accusations, the PMIs repeatedly shifted the blame onto the corrupt political leadership of the country or resource and manpower shortages. Many wrong practices were justified or rationalized and any inward focus seemed to be totally missing. However, as in any organization, things are not all black, and some lower-tier officials showed gratitude toward their seniors who had gone out of their way to help them. Employee 2.4 said: “We were controlling a mob in a political congregation. I went to bring water for my senior and saw him sitting among the force and asking them about their difficulties and any issues that he could help them out. How can we not respect such seniors? But unfortunately such officers are few in number”.

The above discussion shows that in the traditional command and control structure of the police, management and employees were often seen to be moving in opposite directions. The management thought that they would change the lower tiers’ ways of working by tightening the controls. However, this did not happen, as the employees resisted the reforms by making use of various excuses and avoidance tactics. These efforts to change the police were lost in the police management’s psychological politics with the DMs. In similar ways, psychological politics arose between the police management and employees, whereby the reforms challenged the employees’ autonomy and power over the community. Hence, the essence of the reform agenda, to make the police people-friendly, largely failed.