Selenium- and Tellurium-Based Antioxidants for Modulating Inflammation and Effects on Osteoblastic Activity

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Organochalcogen Preparation

2.2. Cell Preparation

2.3. Chemiluminescent Assay for Scavenging H2O2

2.4. Cytotoxicity Study

2.5. H2O2 Toxicity Assay

2.6. Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP) Activity

2.7. Statistical Method

3. Results

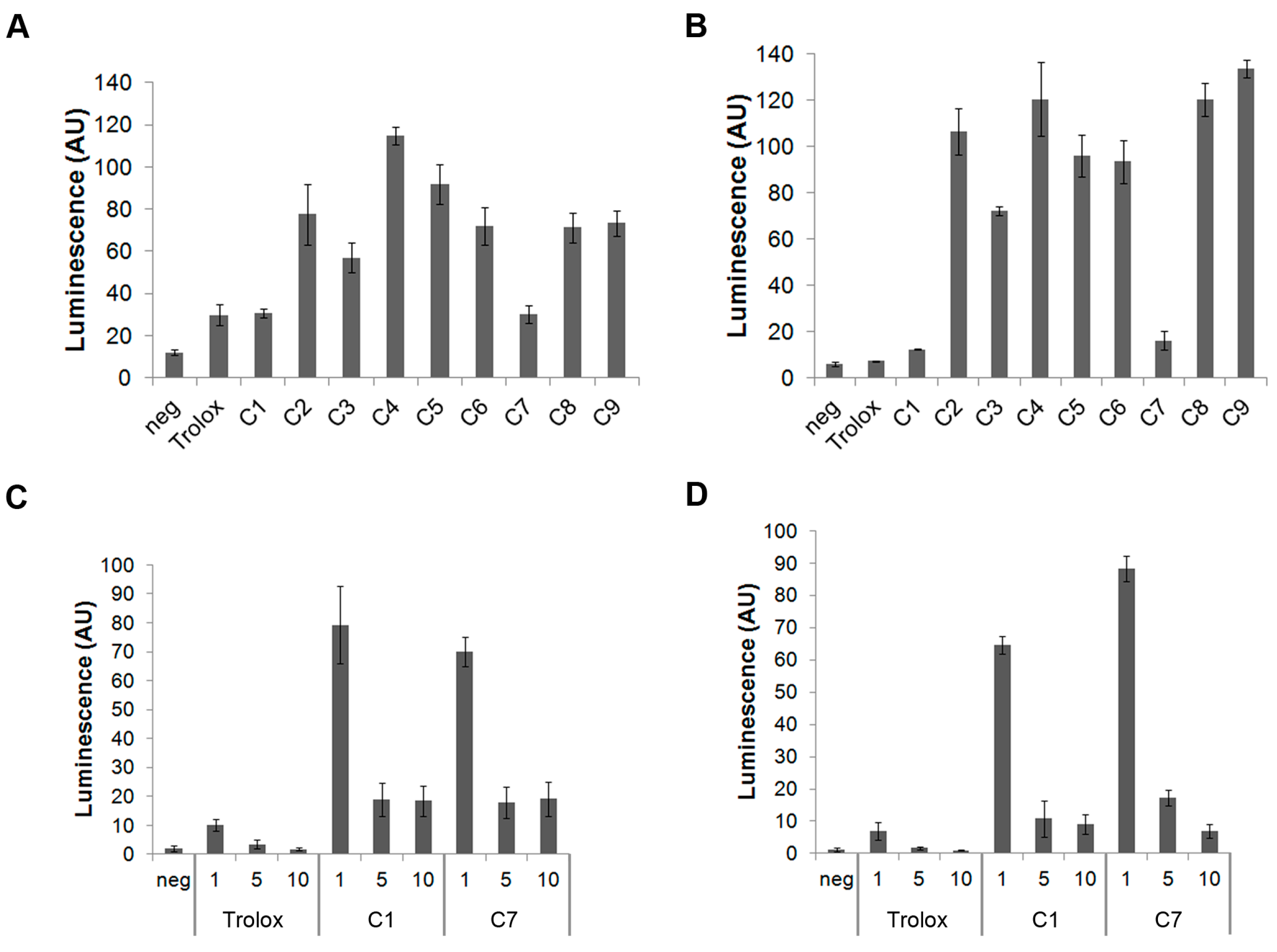

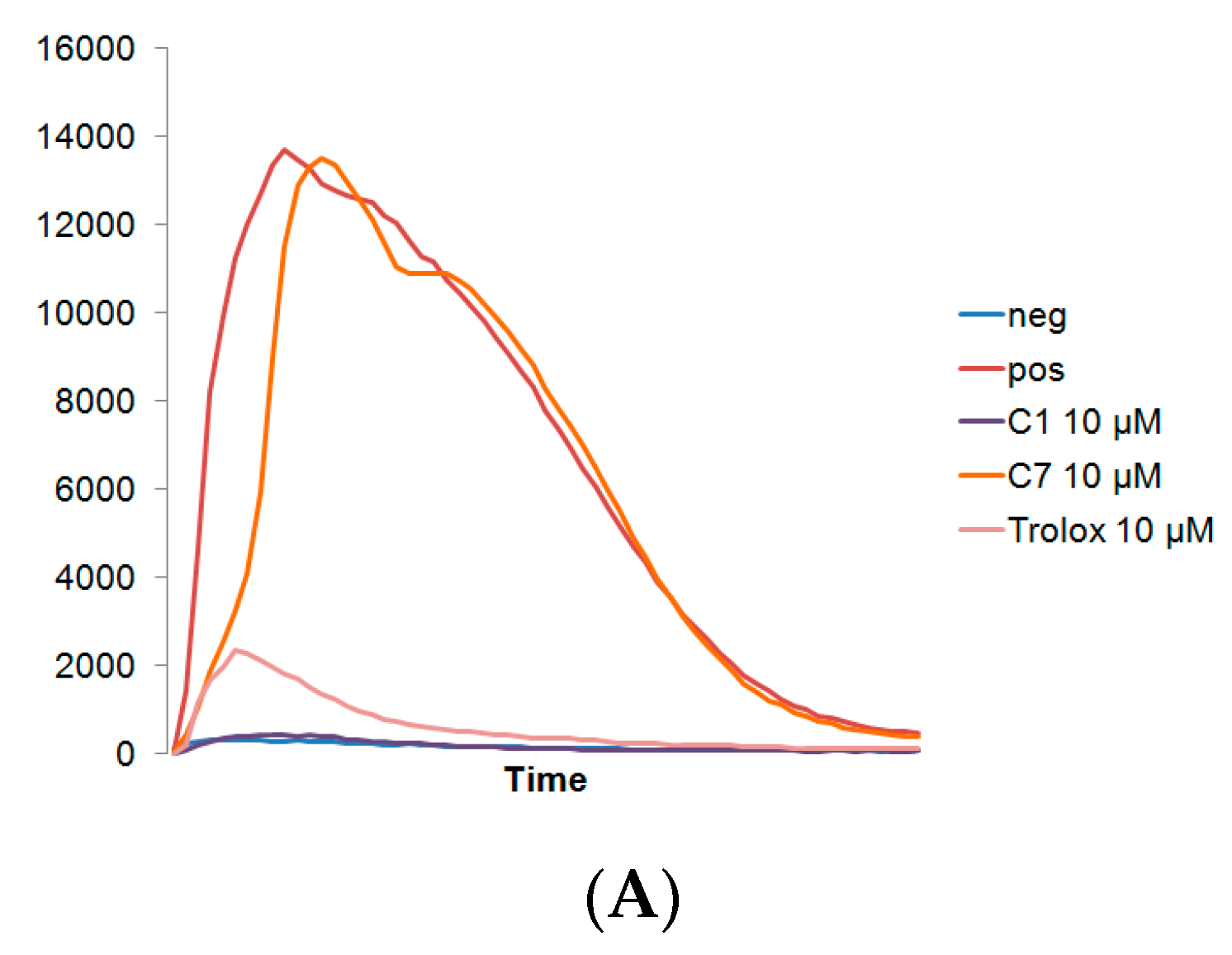

3.1. C1 and C7 Significantly Reduced H2O2 Generated from Immune Cell Lines

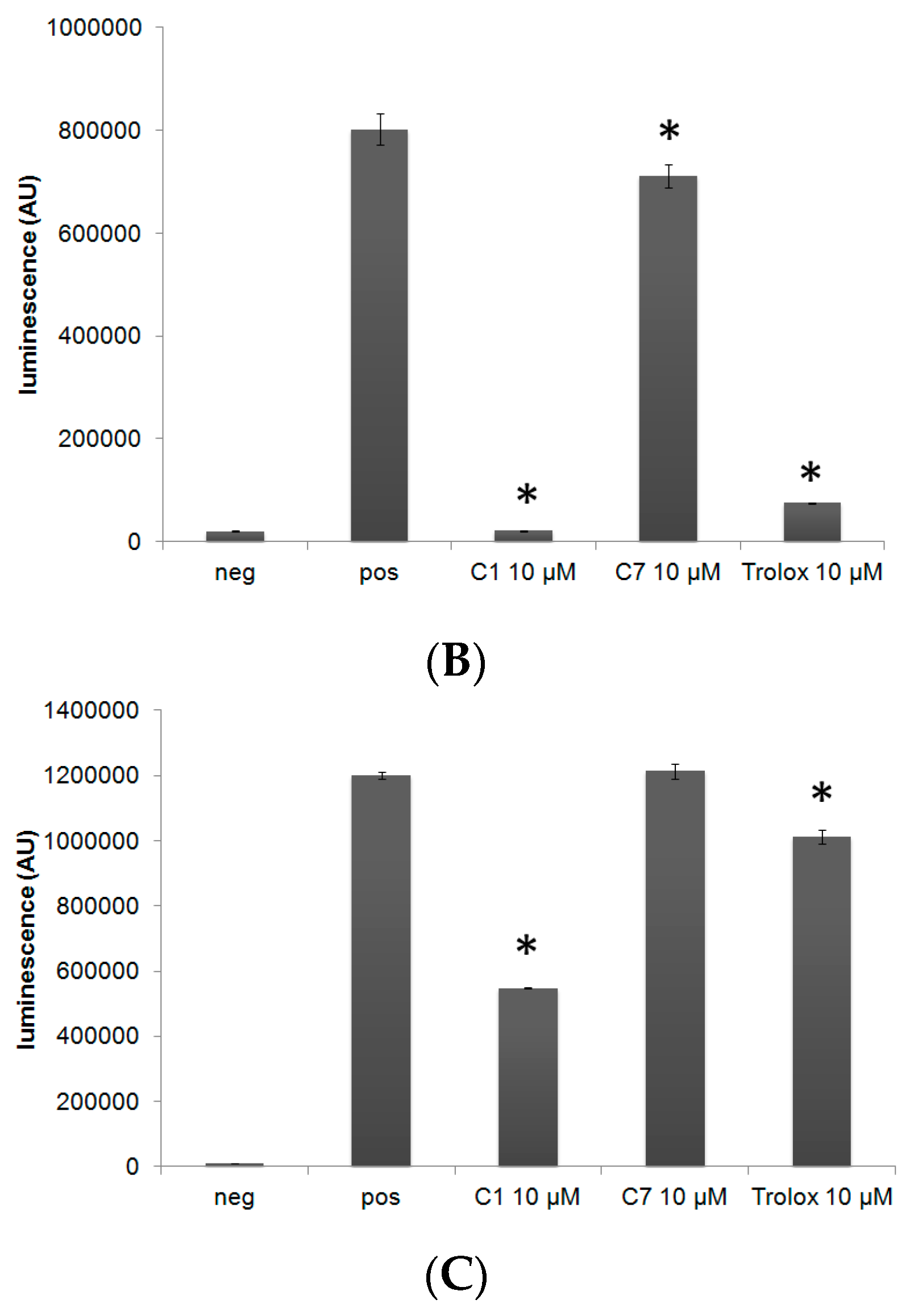

3.2. C1 and C7 Did Not Significantly Affect Cell Viability

3.3. C1 Protects MC3T3-E1 Cells against H2O2 Mediated Toxicity

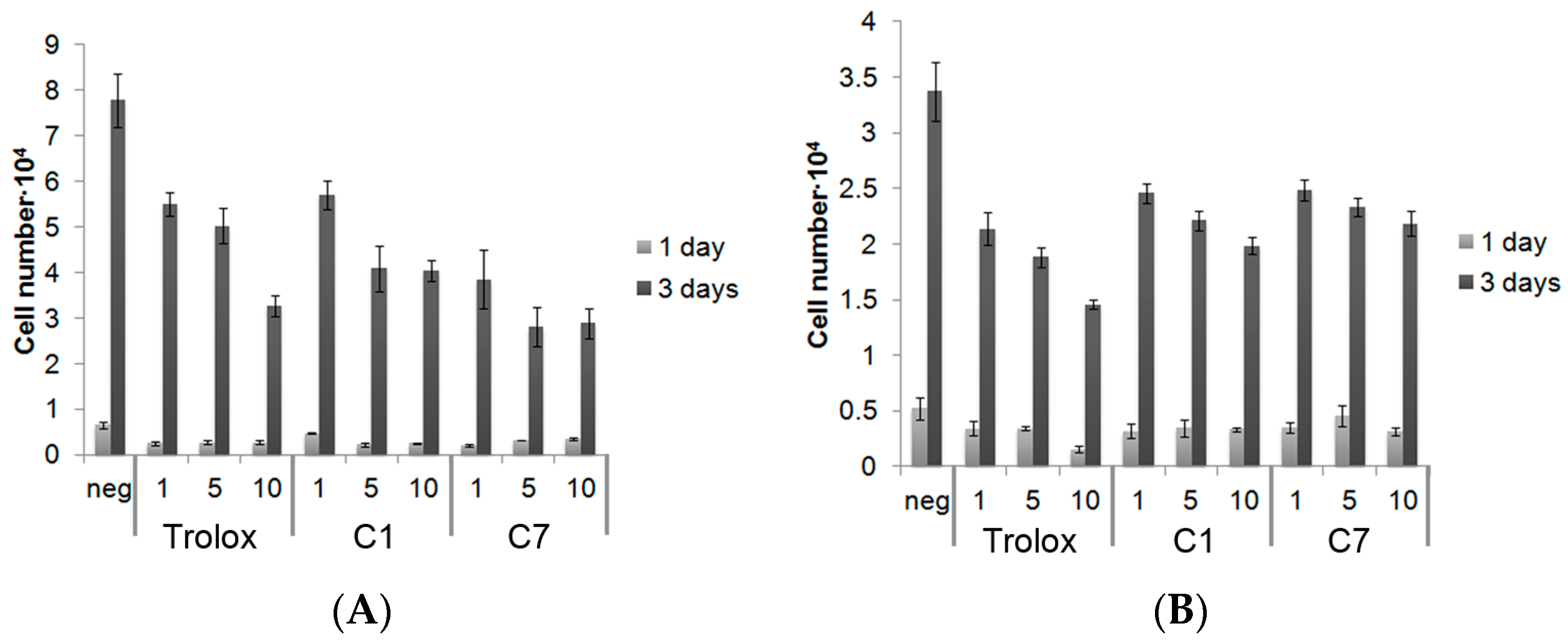

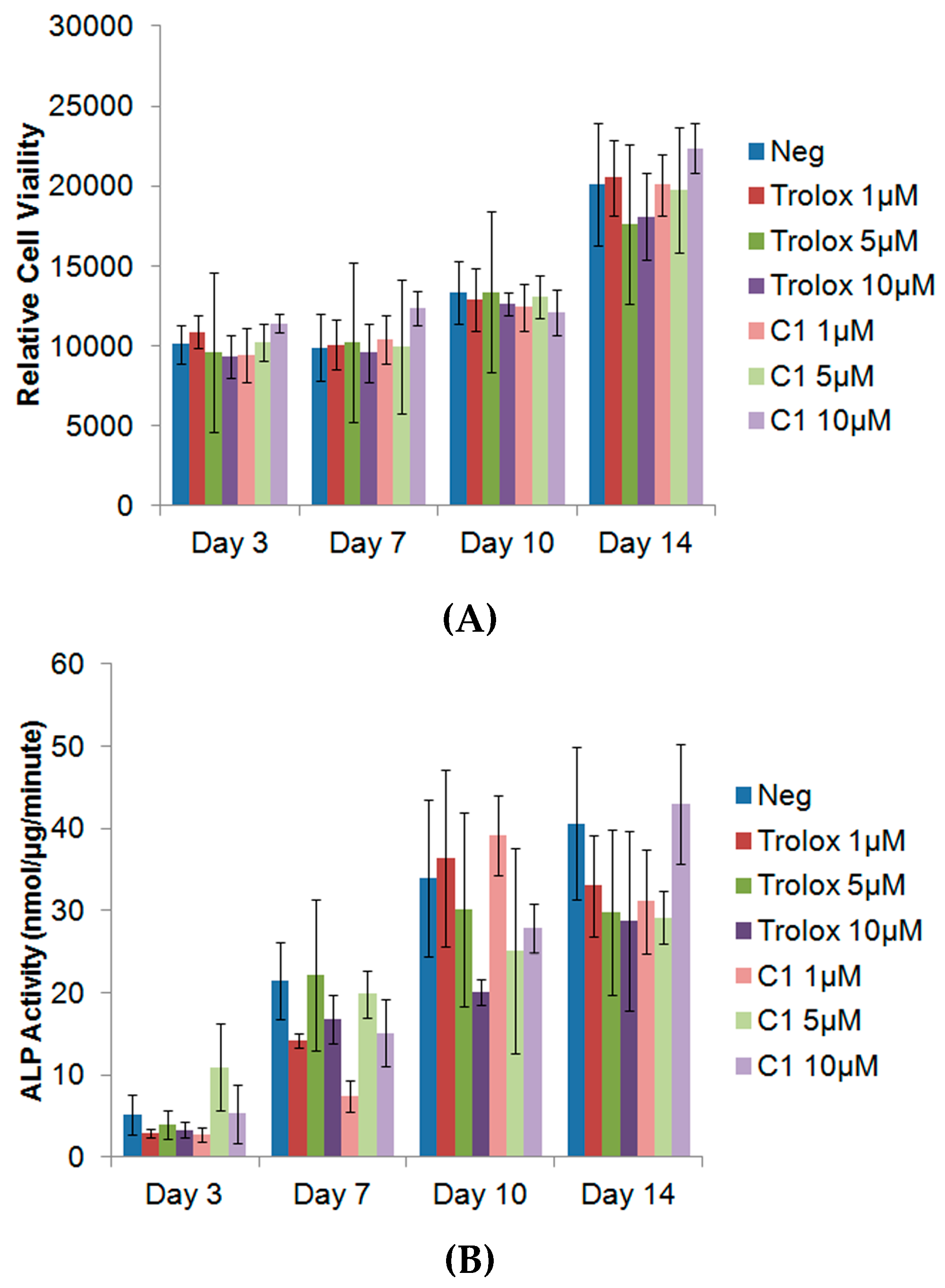

3.4. Exogenous Application of Antioxidants Does Not Affect Endogenous Proliferation or ALP Activity of MC3T3s

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- El Assar, M.; Angulo, J.; Rodriguez-Manas, L. Oxidative stress and vascular inflammation in aging. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2013, 65, 380–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, H.; Kong, Y.; Zhang, H. Oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and aging. J. Signal Transduct. 2012, 2012, 646354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wruck, C.J.; Fragoulis, A.; Gurzynski, A.; Brandenburg, L.O.; Kan, Y.W.; Chan, K.; Hassenpflug, J.; Freitag-Wolf, S.; Varoga, D.; Lippross, S.; et al. Role of oxidative stress in rheumatoid arthritis: Insights from the Nrf2-knockout mice. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2011, 70, 844–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kundu, S.; Ghosh, P.; Datta, S.; Ghosh, A.; Chattopadhyay, S.; Chatterjee, M. Oxidative stress as a potential biomarker for determining disease activity in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Free Radic. Res. 2012, 46, 1482–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cervellati, C.; Bonaccorsi, G.; Cremonini, E.; Bergamini, C.M.; Patella, A.; Castaldini, C.; Ferrazzini, S.; Capatti, A.; Picarelli, V.; Pansini, F.S.; et al. Bone mass density selectively correlates with serum markers of oxidative damage in post-menopausal women. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2013, 51, 333–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sena, L.A.; Chandel, N.S. Physiological roles of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species. Mol. Cell 2012, 48, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, F. Building strong bones: Molecular regulation of the osteoblast lineage. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012, 13, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lean, J.M.; Jagger, C.J.; Kirstein, B.; Fuller, K.; Chambers, T.J. Hydrogen peroxide is essential for estrogen-deficiency bone loss and osteoclast formation. Endocrinology 2005, 146, 728–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altindag, O.; Erel, O.; Soran, N.; Celik, H.; Selek, S. Total oxidative/anti-oxidative status and relation to bone mineral density in osteoporosis. Rheumatol. Int. 2008, 28, 317–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schett, G. Effects of inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines on the bone. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2011, 41, 1361–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almeida, M.; Han, L.; Ambrogini, E.; Bartell, S.M.; Manolagas, S.C. Oxidative stress stimulates apoptosis and activates NF-kappaB in osteoblastic cells via a PKCbeta/p66shc signaling cascade: Counter regulation by estrogens or androgens. Mol. Endocrinol. 2010, 24, 2030–2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartell, S.M.; Kim, H.N.; Ambrogini, E.; Han, L.; Iyer, S.; Serra Ucer, S.; Rabinovitch, P.; Jilka, R.L.; Weinstein, R.S.; Zhao, H.; et al. FoxO proteins restrain osteoclastogenesis and bone resorption by attenuating H2O2 accumulation. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 3773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, D.H.; Lim, B.S.; Lee, Y.K.; Yang, H.C. Effects of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) on alkaline phosphatase activity and matrix mineralization of odontoblast and osteoblast cell lines. Cell Biol. Toxicol. 2006, 22, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arai, M.; Shibata, Y.; Pugdee, K.; Abiko, Y.; Ogata, Y. Effects of reactive oxygen species (ROS) on antioxidant system and osteoblastic differentiation in MC3T3-E1 cells. IUBMB Life 2007, 59, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, D.; Yang, M.; Guo, B.; Cao, J.; Yang, L.; Guo, X.; Li, Y.; Gao, Z. Zinc inhibits H2O2-induced MC3T3-E1 cells apoptosis via MAPK and PI3K/AKT pathways. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2012, 148, 420–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sendur, O.F.; Turan, Y.; Tastaban, E.; Serter, M. Antioxidant status in patients with osteoporosis: A controlled study. Jt. Bone Spine 2009, 76, 514–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarrinkalam, M.R.; Mulaibrahimovic, A.; Atkins, G.J.; Moore, R.J. Changes in osteocyte density correspond with changes in osteoblast and osteoclast activity in an osteoporotic sheep model. Osteoporos Int. 2012, 23, 1329–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, G.M.; Ominsky, M.S.; Boyd, S.K. Bone quality is partially recovered after the discontinuation of RANKL administration in rats by increased bone mass on existing trabeculae: An in vivo micro-CT study. Osteoporos Int. 2011, 22, 931–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mestres, G.; Santos, C.F.; Engman, L.; Persson, C.; Ott, M.K. Scavenging effect of Trolox released from brushite cements. Acta Biomater. 2015, 11, 459–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsukimura, N.; Yamada, M.; Aita, H.; Hori, N.; Yoshino, F.; Chang-Il Lee, M.; Kimoto, K.; Jewett, A.; Ogawa, T. N-acetyl cysteine (NAC)-mediated detoxification and functionalization of poly(methyl methacrylate) bone cement. Biomaterials 2009, 30, 3378–3389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aita, H.; Tsukimura, N.; Yamada, M.; Hori, N.; Kubo, K.; Sato, N.; Maeda, H.; Kimoto, K.; Ogawa, T. N-acetyl cysteine prevents polymethyl methacrylate bone cement extract-induced cell death and functional suppression of rat primary osteoblasts. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2010, 92, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Demerdash, F.M. Antioxidant effect of vitamin E and selenium on lipid peroxidation, enzyme activities and biochemical parameters in rats exposed to aluminium. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2004, 18, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- May, S.W. Selenium-Based Drug Design; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1999; pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson, C.M.; Brattsand, R.; Hallberg, A.; Engman, L.; Persson, J.; Moldeus, P.; Cotgreave, I. Diaryl tellurides as inhibitors of lipid peroxidation in biological and chemical systems. Free Radic. Res. 1994, 20, 401–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kil, J.; Pierce, C.; Tran, H.; Gu, R.; Lynch, E.D. Ebselen treatment reduces noise induced hearing loss via the mimicry and induction of glutathione peroxidase. Hear Res. 2007, 226, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhowmick, D.; Srivastava, S.; D’Silva, P.; Mugesh, G. Highly efficient glutathione peroxidase and peroxiredoxin mimetics protect mammalian cells against oxidative damage. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2015, 54, 8449–8453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobrachinski, F.; da Silva, M.H.; Tassi, C.L.; de Carvalho, N.R.; Dias, G.R.; Golombieski, R.M.; da Silva Loreto, E.L.; da Rocha, J.B.T.; Fighera, M.R.; Soares, F.A.A. Neuroprotective effect of diphenyl diselenide in a experimental stroke model: Maintenance of redox system in mitochondria of brain regions. Neurotox. Res. 2014, 26, 317–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sredni, B.; Geffen-Aricha, R.; Duan, W.; Albeck, M.; Shalit, F.; Lander, H.M.; Kinor, N.; Sagi, O.; Albeck, A.; Yosef, S.; et al. Multifunctional tellurium molecule protects and restores dopaminergic neurons in Parkinson’s disease models. FASEB J. 2007, 21, 1870–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halperin-Sheinfeld, M.; Gertler, A.; Okun, E.; Sredni, B.; Cohen, H.Y. The Tellurium compound, AS101, increases SIRT1 level and activity and prevents type 2 diabetes. Aging 2012, 4, 436–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giles, G.I.; Fry, F.H.; Tasker, K.M.; Holme, A.L.; Peers, C.; Green, K.N.; Klotz, L.-O.; Sies, H.; Jacob, C. Evaluation of sulfur, selenium and tellurium catalysts with antioxidant potential. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2003, 1, 4317–4322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Johansson, H.; Engman, L.; Valgimigli, L.; Amorati, R.; Fumo, M.G.; Pedulli, G.F. Regenerable chain-breaking 2,3-dihydrobenzo[b]selenophene-5-ol antioxidants. J. Org. Chem. 2007, 72, 2583–2595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poon, J.F.; Singh, V.P.; Engman, L. In search of catalytic antioxidants—(Alkyltelluro)phenols, (alkyltelluro)resorcinols, and bis(alkyltelluro)phenols. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 78, 6008–6015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, V.P.; Poon, J.F.; Butcher, R.J.; Engman, L. Pyridoxine-derived organoselenium compounds with glutathione peroxidase-like and chain-breaking antioxidant activity. Chem. Eur. J. 2014, 20, 12563–12571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, V.P.; Poon, J.F.; Butcher, R.J.; Lu, X.; Mestres, G.; Ott, M.K.; Engman, L. Effect of a Bromo Substituent on the Glutathione Peroxidase Activity of a Pyridoxine-like Diselenide. J. Org. Chem. 2015, 80, 7385–7395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johansson, H.; Svartstrom, O.; Phadnis, P.; Engman, L.; Ott, M.K. Exploring a synthetic organoselenium compound for antioxidant pharmacotherapy—Toxicity and effects on ROS-production. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2010, 18, 1783–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, V.P.; Singh, H.B.; Butcher, R.J. Synthesis of cyclic selenenate/seleninate esters stabilized by ortho-nitro coordination: Their glutathione peroxidase-like activities. Chem. Asian J. 2011, 6, 1431–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, V.P.; Poon, J.-F.; Engman, L. Turning Pyridoxine into a Catalytic Chain-Breaking and Hydroperoxide-Decomposing Antioxidant. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 78, 1478–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Dahlgren, C.; Elwing, H.; Lundqvist, H. A simple chemiluminescence assay for the determination of reactive oxygen species produced by human neutrophils. J. Immunol. Methods 1996, 192, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanislawski, L.; Soheili-Majd, E.; Perianin, A.; Goldberg, M. Dental restorative biomaterials induce glutathione depletion in cultured human gingival fibroblast: Protective effect of N-acetyl cysteine. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2000, 51, 469–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamad, I.; Arda, N.; Pekmez, M.; Karaer, S.; Temizkan, G. Intracellular scavenging activity of Trolox (6-hydroxy-2,5,7,8-tetramethylchromane-2-carboxylic acid) in the fission yeast, Schizosaccharomyces pombe. J. Nat. Sci. Biol. Med. 2010, 1, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.B.; Zhong, Z.M.; Hou, G.; Jiang, H.; Chen, J.T. Involvement of oxidative stress in age-related bone loss. J. Surg. Res. 2011, 169, e37–e42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ueno, T.; Yamada, M.; Igarashi, Y.; Ogawa, T. N-acetyl cysteine protects osteoblastic function from oxidative stress. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2011, 99, 523–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamada, M.; Tsukimura, N.; Ikeda, T.; Sugita, Y.; Att, W.; Kojima, N.; Kubo, K.; Ueno, T.; Sakuraic, K.; Ogawa, T. N-acetyl cysteine as an osteogenesis-enhancing molecule for bone regeneration. Biomaterials 2013, 34, 6147–6156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janssen-Heininger, Y.M.; Mossman, B.T.; Heintz, N.H.; Forman, H.J.; Kalyanaraman, B.; Finkel, T.; Stamler, J.S.; Rhee, S.G.; van der Vliet, A. Redox-based regulation of signal transduction: Principles, pitfalls, and promises. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2008, 45, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romagnoli, C.; Marcucci, G.; Favilli, F.; Zonefrati, R.; Mavilia, C.; Galli, G.; Tanini, A.; Iantomasi1, T.; Brandi, M.L.; Vincenzini, M.T. Role of GSH/GSSG redox couple in osteogenic activity and osteoclastogenic markers of human osteoblast-like SaOS-2 cells. FEBS J. 2013, 280, 867–879. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mandal, C.C.; Ganapathy, S.; Gorin, Y.; Mahadev, K.; Block, K.; Abboud, H.E.; Harris, S.E.; Ghosh-Choudhury, G.; Ghosh-Choudhury, N. Reactive oxygen species derived from Nox4 mediate BMP2 gene transcription and osteoblast differentiation. Biochem. J. 2011, 433, 393–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soeta, S.; Higuchi, M.; Yoshimura, I.; Itoh, R.; Kimura, N.; Aamsaki, H. Effects of vitamin E on the osteoblast differentiation. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2010, 72, 951–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ha, H.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, H.N.; Lee, Z.H. alpha-Tocotrienol inhibits osteoclastic bone resorption by suppressing RANKL expression and signaling and bone resorbing activity. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2011, 406, 546–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujita, K.; Iwasaki, M.; Ochi, H.; Fukuda, T.; Ma, C.; Miyamoto, T.; Takitani, K.; Negishi-Koga, T.; Sunamura, S.; Kodama, T.; et al. Vitamin E decreases bone mass by stimulating osteoclast fusion. Nat. Med. 2012, 18, 589–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giorgio, M.; Trinei, M.; Migliaccio, E.; Pelicci, P.G. Hydrogen peroxide: A metabolic by-product or a common mediator of ageing signals? Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007, 8, 722–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, X.C.; Lu, D.; Bai, J.; Zheng, H.; Ke, Z.Y.; Li, X.M.; Luo, S.Q. Oxidative stress inhibits osteoblastic differentiation of bone cells by ERK and NF-kappaB. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004, 314, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almeida, M.; Han, L.; Martin-Millan, M.; O’Brien, C.A.; Manolagas, S.C. Oxidative stress antagonizes Wnt signaling in osteoblast precursors by diverting beta-catenin from T cell factor- to forkhead box O-mediated transcription. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 27298–27305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lu, X.; Mestres, G.; Singh, V.P.; Effati, P.; Poon, J.-F.; Engman, L.; Ott, M.K. Selenium- and Tellurium-Based Antioxidants for Modulating Inflammation and Effects on Osteoblastic Activity. Antioxidants 2017, 6, 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox6010013

Lu X, Mestres G, Singh VP, Effati P, Poon J-F, Engman L, Ott MK. Selenium- and Tellurium-Based Antioxidants for Modulating Inflammation and Effects on Osteoblastic Activity. Antioxidants. 2017; 6(1):13. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox6010013

Chicago/Turabian StyleLu, Xi, Gemma Mestres, Vijay Pal Singh, Pedram Effati, Jia-Fei Poon, Lars Engman, and Marjam Karlsson Ott. 2017. "Selenium- and Tellurium-Based Antioxidants for Modulating Inflammation and Effects on Osteoblastic Activity" Antioxidants 6, no. 1: 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox6010013