Membranes for Environmentally Friendly Energy Processes

Abstract

:1. Introduction

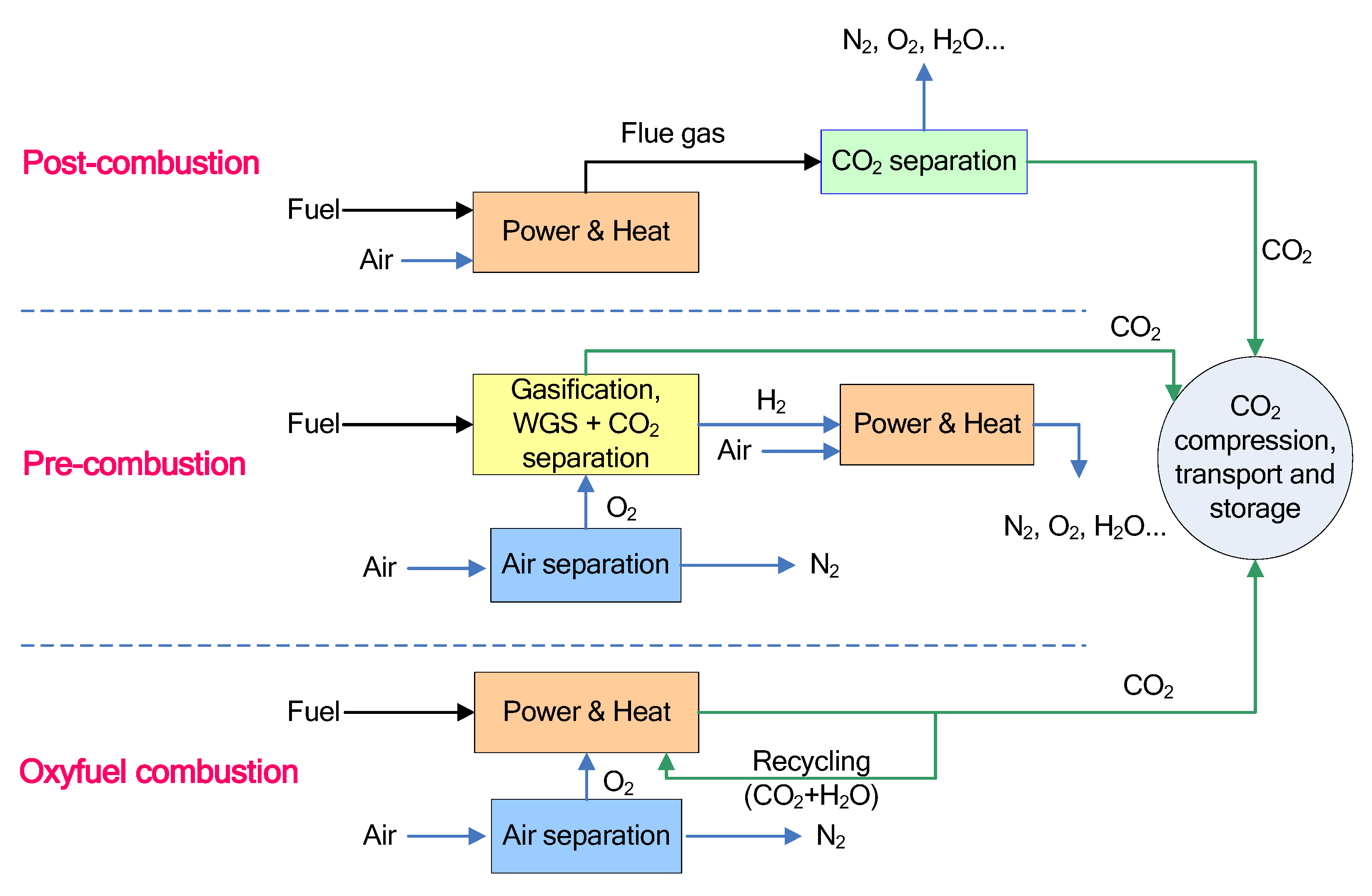

2. CO2 Capture from Power Plants

2.1. Post-Combustion CO2 Capture

| Flue gas characteristic | Challenges related to membrane process | Potential solution | Membrane requirement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low CO2 concentration | Large quantities of gas need to be treated | Scaling up of membrane unit | High CO2 selectivity and permeance, low cost |

| Low pressure | Low driving force | Compression in feed or vacuum in permeate streams | High CO2 selectivity and permeance |

| High temperature | Most polymer membrane cannot be used at >100 °C | Cooling down 40–60 °C | High thermal resistance |

| Harmful componentsin flue gas | SO2, NOx | Removal of containments or developing chemically resistant membranes | High chemical and aging resistance |

| Water | Water can pass through the membranes, corrosion of pipeline during CO2 transportation | Drying of flue gas | Low H2O/CO2 selectivity |

2.2. Pre-Combustion CO2 Capture

2.3. Oxyfuel Combustion CO2 Capture

3. Natural Gas Sweetening

4. Biogas Upgrading

| Process | Composition (vol %) * | H2S/SO2 (ppm) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CO2 | CH4 | N2 | O2 | H2O | ||

| Farm biogas plant | 37–38 | 55–58 | <2 | <1 | 4–7 | 32–169 |

| Sewage digester | 38.6 | 57.8 | 3.7 | 0 | 4–7 | 62.9 |

| Landfill | 37–41 | 47–57 | <1 | <1 | 4–7 | 36–115 |

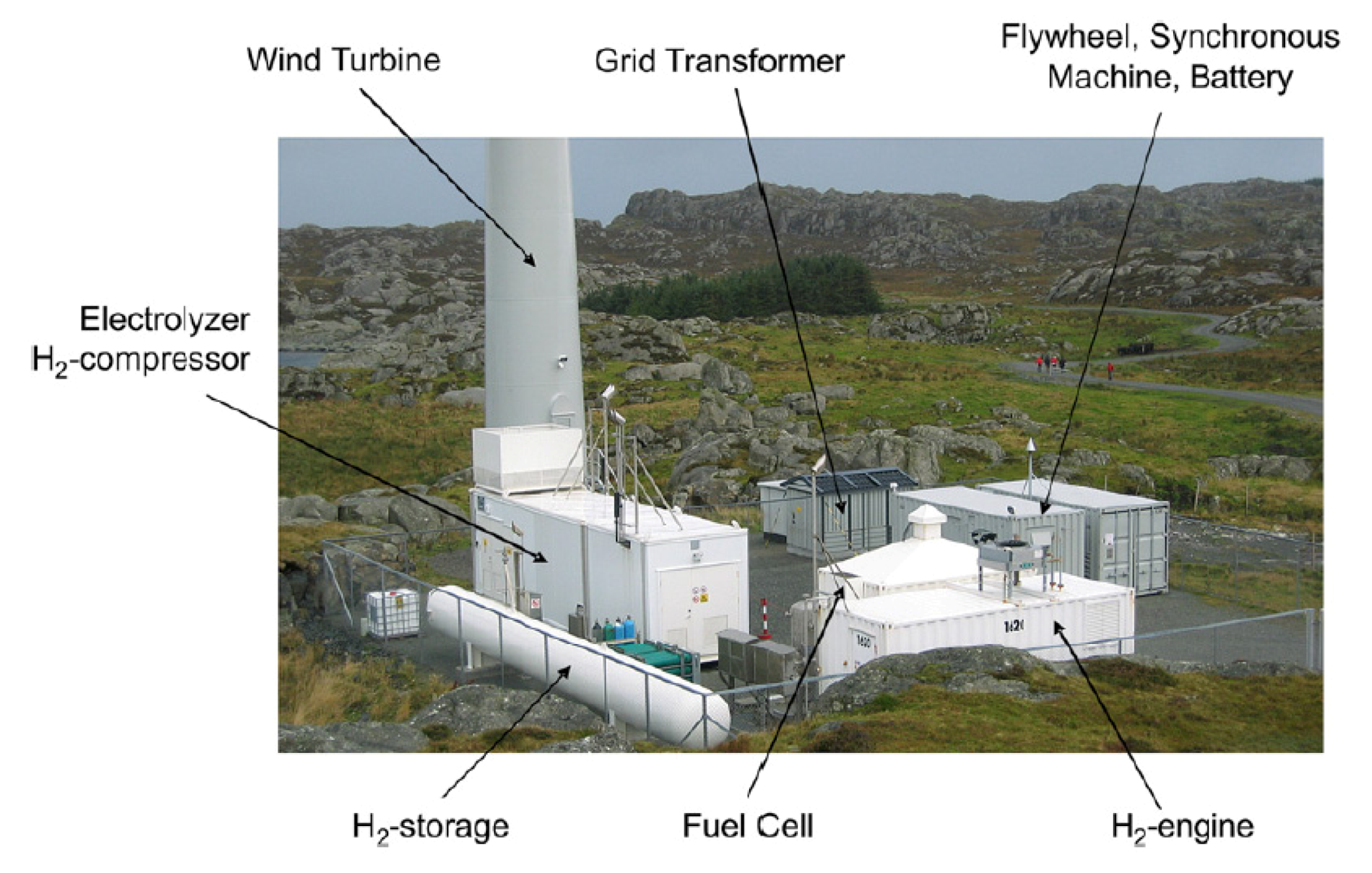

5. Hydrogen Production/Recovery

| Separation | Process | Membrane | Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| H2 production by water electrolysis | H2 PEM electrolyzer | PEM, FuelGen® | Commercial production |

| Wind/H2 power system | PEM electrolyzer and fuel cells | PEM | Pilot-scale demonstration |

| H2/CO | Methanol steam reforming membrane reactors | Pd and CMS membrane | Lab-scale |

| H2/CO | Adjustment of H2/CO ratio in syngas | Silicon rubber, polyimide | Plant installed |

| H2/N2 | Ammonia purge gas | Prism® | Plant installed |

| H2/Hydrocarbon | H2 recovery in refineries | Silicon rubber, polyimide | Plant installed |

| H2/CH4 | Natural gas network transportation | Carbon molecular sieve membranes | Lab-scale |

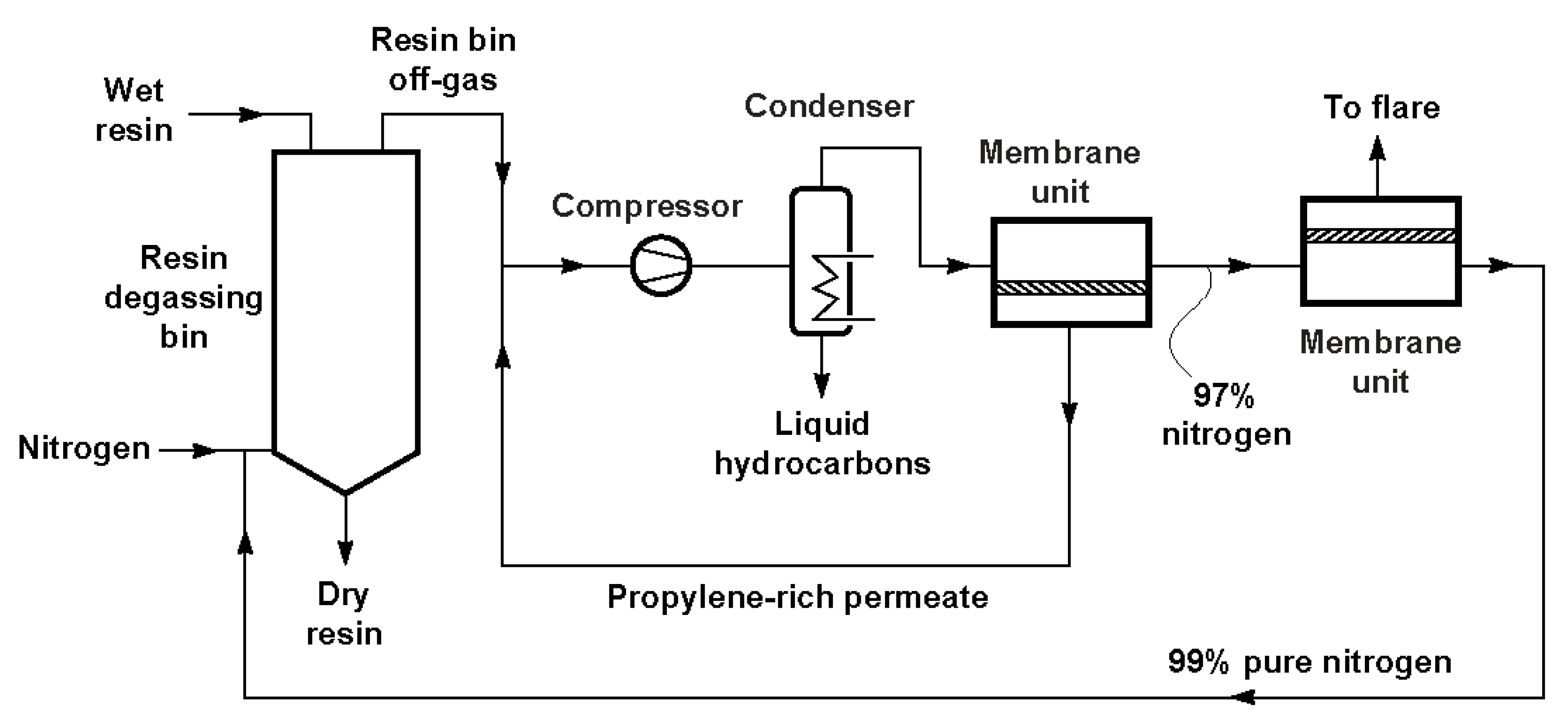

6. Volatile Organic Compounds Recovery

7. Pressure Retarded Osmosis

8. Future Directions

- Membrane transport properties (pemeance and selectivity)

- Mechanical strength, chemical and thermal stability under a specific operating condition

- Membrane durability over the long term by being exposed to real process conditions

- Membrane module design

- Process design, simulation, optimization and integration

Acknowledgements

References

- International Energy Outlook 2011. Available online: http://www.eia.gov/ieo/pdf/0484(2011).pdf (accessed on 16 October 2012).

- Michael, K.; Golab, A.; Shulakova, V.; Ennis-Kinga, J.; Allinson, G.; Sharma, S.; Aiken, T. Geological storage of CO2 in saline aquifers—A review of the experience from existing storage operations. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2010, 4, 659–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- New Way to Convert CO2 into Methanol. Available online: http://www.alternative-energy-news.info/new-way-to-convert-CO2-into-methanol/ (accessed on 16 October 2012).

- Exxon Makes Big Investment in Algae Biofuels. Available online: http://www.heatusa.com/energy-conservation/exxon-big-investment-algae-biofuels/ (accessed on 16 October 2012).

- Evans, A.; Strezov, V.; Evans, T.J. Assessment of sustainability indicators for renewable energy technologies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2009, 13, 1082–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loeb, S. Production of energy from concentrated brines by pressure-retarded osmosis: I. Preliminary technical and economic correlations. J. Membr. Sci. 1976, 1, 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achilli, A.; Childress, A.E. Pressure retarded osmosis: From the vision of Sidney Loeb to the first prototype installatio—Review. Desalination 2010, 261, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ockwig, N.W.; Nenoff, T.M. Membranes for Hydrogen Separation. Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 4078–4110. [Google Scholar]

- Bredesen, R.; Jordal, K.; Bolland, O. High-temperature membranes in power generation with CO2 capture. Chem. Eng. Process. 2004, 43, 1129–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunetti, A.; Scuraa, F.; Barbieria, G.; Drioli, E. Membrane technologies for CO2 separation. J. Membr. Sci. 2010, 359, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagg, M.B.; Lindbrathen, A. CO2 Capture from Natural Gas Fired Power Plants by Using Membrane Technology. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2005, 44, 7668–7675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Zou, J.; Ho, W.S.W. Carbon Dioxide Capture Using a CO2-Selective Facilitated Transport Membrane. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2008, 47, 1261–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.; Hägg, M.-B. A feasibility study of CO2 capture from flue gas by a facilitated transport membrane. J. Membr. Sci. 2010, 359, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Xua, Z.; Fanb, M.; Guptaa, R.; Slimanec, R.B.; Blandd, A.E.; Wrighte, I. Progress in carbon dioxide separation and capture: A review. J. Environ. Sci. 2008, 20, 14–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, R.W. Membranes for Vapor/Gas Separation. Available online: http://www.mtrinc.com/publications/MT01%20Fane%20Memb%20for%20VaporGas_Sep%202006%20Book%20Ch.pdf (accessed on 16 October 2012).

- Baker, R.W.; Lokhandwala, K. Natural Gas Processing with Membranes: An Overview. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2008, 47, 2109–2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, L.; Hussain, A.; Follmann, M.; Melin, T.; Hägg, M.B. CO2 removal from natural gas by employing amine absorption and membrane technology—A technical and economical analysis. Chem. Eng. J. 2011, 172, 952–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makaruk, A.; Miltner, M.; Harasek, M. Membrane biogas upgrading processes for the production of natural gas substitute. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2010, 74, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Hägg, M.-B. Techno-economic evaluation of biogas upgrading process using CO2 facilitated transport membrane. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2010, 4, 638–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hydrogen Fueling Systems. Available online: http://www.protononsite.com/technology/hydrogen-fueling-systems.html (accessed on 16 October 2012).

- Utsira Wind Power and Hydrogen Plant. Available online: http://www.iphe.net/docs/Renew_H2_Ustira.pdf (accessed on 16 October 2012).

- Sá, S.; Silvaa, H.; Sousaa, J.M.; Mendes, A. Hydrogen production by methanol steam reforming in a membrane reactor: Palladium vs. carbon molecular sieve membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 2009, 339, 160–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carapellucci, R.; Milazzo, A. Membrane systems for CO2 capture and their integration with gas turbine plants. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. A J. Power Energy 2003, 217, 505–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reijerkerk, S.R. Polyether Based Block Copolymer Membranes for CO2 Separation.

- Lin, H.; Freeman, B.D. Materials selection guidelines for membranes that remove CO2 from gas mixtures. J. Mol. Struct. 2005, 739, 57–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Kim, T.-J.; Hägg, M.-B. Facilitated transport of CO2 in novel PVAm/PVA blend membrane. J. Membr. Sci. 2009, 340, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandru, M.; Haukebø, S.H.; Hägg, M.-B. Composite hollow fiber membranes for CO2 capture. J. Membr. Sci. 2010, 346, 172–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Hägg, M.-B. Hollow fiber carbon membranes: Investigations for CO2 capture. J. Membr. Sci. 2011, 378, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardo, P.; Drioli, E. Membrane gas separation progresses for process intensification strategy in the petrochemical industry. Pet. Chem. 2010, 50, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardo, P.; Drioli, E.; Golemme, G. Membrane gas separation: A review/state of the art. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2009, 48, 4638–4663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robeson, L.M. The upper bound revisited. J. Membr. Sci. 2008, 320, 390–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasten, E.; Hagen, G.; Tunold, R. Electrocatalysis in water electrolysis with solid polymer electrolyte. Electrochim. Acta 2003, 48, 3945–3952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigoriev, S.A.; Porembsky, V.I.; Fateev, V.N. Pure hydrogen production by PEM electrolysis for hydrogen energy. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2006, 31, 171–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, Y.; Uchinashia, S.; Saiharaa, Y.; Kikuchic, K.; Okayac, T.; Ogumib, Z. Dissolution of hydrogen and the ratio of the dissolved hydrogen content to the produced hydrogen in electrolyzed water using SPE water electrolyzer. Electrochim. Acta 2003, 48, 4013–4019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achilli, A.; Cath, T.Y.; Childress, A.E. Power generation with pressure retarded osmosis: An experimental and theoretical investigation. J. Membr. Sci. 2009, 343, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Penga, X.; Tang, C.Y.; Fu, Q.S.; Nie, S. Effect of draw solution concentration and operating conditions on forward osmosis and pressure retarded osmosis performance in a spiral wound module. J. Membr. Sci. 2010, 348, 298–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Lee, J.; Kim, J.H. Overview of pressure-retarded osmosis (PRO) process and hybrid application to sea water reverse osmosis process. Desalin. Water Treat. 2012, 43, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skilhagen, S.E.; Dugstad, J.E.; Aaberg, R.J. Osmotic power—power production based on the osmotic pressure difference between waters with varying salt gradients. Desalination 2008, 220, 476–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CO2 Capture and Storage-VGB Report on the State of the Art. Available online: http://www.vgb.org/vgbmultimedia/Fachgremien/Umweltschutz/VGB+Capture+and+Storage.pdf (accessed on 16 October 2012).

- Favre, E. Membrane processes and postcombustion carbon dioxide capture: Challenges and prospects. Chem. Eng. J. 2011, 171, 782–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hägg, M.B.; Sandru, M.; Kim, T.J.; Capala, W.; Huijbers, M. Report on pilot scale testing and further development of a facilitated transport membrane for CO2 capture from power plants. In Presented at Euromembrane 2012, London, UK, September 2012.

- He, X. Development of Hollow Fiber Carbon Membranes for CO2 Separation.

- He, X.; Lie, J.A.; Sheridan, E.; Hägg, M.-B. Preparation and characterization of hollow fiber carbon membranes from cellulose acetate precursors. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2011, 50, 2080–2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Lie, J.A.; Sheridan, E.; Hägg, M.-B. CO2 capture by hollow fibre carbon membranes: Experiments and process simulations. Energy Procedia 2009, 1, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, A.B.; Rubin, E.S. A Technical, Economic, and Environmental Assessment of Amine-Based CO2 Capture Technology for Power Plant Greenhouse Gas Control. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2002, 36, 4467–4475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merkel, T.C.; Lin, H.; Wei, X.; Baker, R. Power plant post-combustion carbon dioxide capture: An opportunity for membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 2010, 359, 126–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Integrating Mea Regeneration with CO2 Compression and Peaking to Reduce CO2 Capture Costs. Available online: http://trimeric.com/Report%20060905.pdf (accessed on 16 October 2012).

- Grainger, D. Development of Carbon Membranes for Hydrogen Recovery.

- Zhao, W.; He, G.; Nie, F.; Zhang, L.; Feng, H.; Liu, H. Membrane liquid loss mechanism of supported ionic liquid membrane for gas separation. J. Membr. Sci. 2012, 411–412, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cserjési, P.; Nemestóthy, N.; Bélafi-Bakó, K. Gas separation properties of supported liquid membranes prepared with unconventional ionic liquids. J. Membr. Sci. 2010, 349, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchytil, P.; Schauer, J.; Petrychkovych, R.; Setnickova, K.; Suen, S.Y. Ionic liquid membranes for carbon dioxide–methane separation. J. Membr. Sci. 2011, 383, 262–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, L.A.; Crespo, J.G.; Coelhoso, I.M. Gas permeation studies in supported ionic liquid membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 2010, 357, 160–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.-H.; Baek, I.-H.; Hong, S.-U.; Lee, H.-K. Study on immobilized liquid membrane using ionic liquid and PVDF hollow fiber as a support for CO2/N22 separation. J. Membr. Sci. 2011, 372, 346–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krull, F.F.; Fritzmann, C.; Melin, T. Liquid membranes for gas/vapor separations. J. Membr. Sci. 2008, 325, 509–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dindore, V.Y.; Brilman, D.W.F.; Feron, P.H.M.; Versteeg, G.F. CO2 absorption at elevated pressures using a hollow fiber membrane contactor. J. Membr. Sci. 2004, 235, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottino, A.; Capannelli, G.; Comite, A.; Di Felice, R.; Firpo, R. CO2 removal from a gas stream by membrane contactor. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2008, 59, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chabanon, E.; Roizard, D.; Favre, E. Membrane contactors for postcombustion carbon dioxide capture: A comparative study of wetting resistance on long time scales. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2011, 50, 8237–8244. [Google Scholar]

- de Montigny, D.; Tontiwachwuthikul, P.; Chakma, A. Using polypropylene and polytetrafluoroethylene membranes in a membrane contactor for CO2 absorption. J. Membr. Sci. 2006, 277, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feron, P.H.M.; Jansen, A.E. CO2 separation with polyolefin membrane contactors and dedicated absorption liquids: performances and prospects. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2002, 27, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeon, S.-H.; Lee, K.-S.; Sea, B.; Park, Y.-I.; Lee, K.-H. Application of pilot-scale membrane contactor hybrid system for removal of carbon dioxide from flue gas. J. Membr. Sci. 2005, 257, 156–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.-L.; Chen, B.-H. Review of CO2 absorption using chemical solvents in hollow fiber membrane contactors. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2005, 41, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansourizadeh, A.; Ismail, A.F. Hollow fiber gas-liquid membrane contactors for acid gas capture: A review. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009, 171, 38–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholes, C.A.; Smith, K.H.; Kentish, S.E.; Stevens, G.W. CO2 capture from pre-combustion processes—Strategies for membrane gas separation. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2010, 4, 739–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Lin, Y.S.; Li, Y.; Zhang, B. Chemical Stability and Its Improvement of Palladium-Based Metallic Membranes. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2004, 43, 6920–6930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, T.A.; Kaleta, T.; Stange, M.; Bredesen, R. Development of thin binary and ternary Pd-based alloy membranes for use in hydrogen production. J. Membr. Sci. 2011, 383, 124–134. [Google Scholar]

- Yun, S.; Oyama, S.T. Correlations in palladium membranes for hydrogen separation: A review. J. Membr. Sci. 2011, 375, 28–45. [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan, G.; Steele, D.; O’Brien, K.; Callahan, R.; Berchtold, K.; Figueroa, J. Simulation of a process to capture CO2 from IGCC syngas using a high temperature PBI membrane. Energy Procedia 2009, 1, 4079–4088. [Google Scholar]

- Grainger, D.; Hägg, M.-B. Techno-economic evaluation of a PVAm CO2-selective membrane in an IGCC power plant with CO2 capture. Fuel 2008, 87, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, M.A.; Badr, H.M.; Ahmed, S.F.; Ben-Mansour, R.; Mezghani, K.; Imashuku, S.; la O', G.J.; Shao-Horn, Y.; Mancini, N.D.; Mitsos, A.; Kirchen, P.; Ghoneim, A.F. A review of recent developments in carbon capture utilizing oxy-fuel combustion in conventional and ion transport membrane systems. Int. J. Energy Res. 2011, 35, 741–764. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, X.; Pang, Z.; Li, K. Oxygen production using La0.6Sr0.4Co0.2Fe0.8O3−α (LSCF) perovskite hollow fibre membrane modules. J. Membr. Sci. 2008, 310, 550–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Gavalas, G.R. Oxygen selective ceramic hollow fiber membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 2005, 246, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, P.A.; Foster, E.P.; Gunardson, H.H. ITM oxygen for gasification. In SPE/PS-CIM/CHOA International Thermal Operations and Heavy Oil Symposium; Society of Petroleum Engineers: Calgary, Alberta, Canada, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Clements, B.R.; Zheng, L.; Pomalis, R. Next generation oxy-fired systems: Potential for energy efficiency improvement through pressurization. In ASME 2009 3rd International Conference of Energy Sustainability, San Francisco, California, USA, 19–23 July 2009.

- Gazzino, M.; Benelli, G. Pressurized oxy-coal combustion Rankine-cycle for future zero emission power plants: Process design and energy analysis. In The 2nd International Conference on Energy Sustainability, Jacksonville, FL, USA, 10–14 August 2008.

- Fassbender, A. Simplification of carbon capture power plants using pressurized oxyfuel. In The 32nd International Technical Conference on Coal Utilization and Fuel Systems, Clearwater, FL, USA; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Fassbender, A.; Tao, L.; Henry, R. Physical properties and liquid vapor equilibrium of pressurized CO2 rich gases from pressurized oxy-fuel combustion of coal. In The 33rdInternational Technical Conference on Coal Utilization and Fuel Systems, Clearwater, FL, USA, 2008.

- Pomalis, R.; Zheng, L.; Clements, B. ThermoEnergy integrated power system economics. In The 32nd International Technical Conference on Coal Utilization and Fuel Systems, Clearwater, FL, USA, 2007.

- Callison, A.; Davidson, G. Offshore processing plant uses membranes for CO2 removal. Oil Gas J. 2007, 105, 56–65. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, L.; Kim, T.-J.; Sandru, M.; Hägg, M.-B. PVA/PVAm blend FSC membrane for natural gas sweetening. In Proceedings of the 1st Annual Gas Processing Symposium, Doha, Qatar, 2009.

- Donohue, M.D.; Minhas, B.S.; Lee, S.Y. Permeation behavior of carbon dioxide-methane mixtures in cellulose acetate membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 1989, 42, 197–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wind, J.D.; Paul, D.R.; Koros, W.J. Natural gas permeation in polyimide membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 2004, 228, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wind, J.D.; Staudt-Bickel, C.; Paul, D.R.; Koros, W.J. The effects of crosslinking chemistry on CO2 plasticization of polyimide gas separation membranes. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2002, 41, 6139–6148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, R.T.; Lee, J.S.; Bae, T.-H.; Ward, J.K.; Johnson, J.R. CO2-CH4 permeation in high zeolite 4A loading mixed matrix membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 2011, 367, 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Hägg, M.B. Hybrid fixed-site-carrier membranes for CO2/CH4 separation. In Euromembrane 2012, London, UK, September 2012.

- Bhide, B.D.; Voskericyan, A.; Stern, S.A. Hybrid processes for the removal of acid gases from natural gas. J. Membr. Sci. 1998, 140, 27–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.W.; Hägg, M.-B. Natural gas sweetening—the effect on CO2–CH4 separation after exposing a facilitated transport membrane to hydrogen sulfide and higher hydrocarbons. J. Membr. Sci. 2012, 423–424, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.W.; Hägg, M.-B. Effect of monoethylene glycol and triethylene glycol contamination on CO2/CH4 separation of a facilitated transport membrane for natural gas sweetening. J. Membr. Sci. 2012, 423–424, 150–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasi, S.; Veijanen, A.; Rintala, J. Trace compounds of biogas from different biogas production plants. Energy 2007, 32, 1375–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasi, S.; Läntelä, J.; Veijanen, A.; Rintala, J. Landfill gas upgrading with countercurrent water wash. Waste Manag. 2008, 28, 1528–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaur, A.; Park, J.-W.; Maken, S.; Song, H.-J.; Park, J.-J. Landfill gas (LFG) processing via adsorption and alkanolamine absorption. Fuel Process. Technol. 2010, 91, 635–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaur, A.; Park, J.-W.; Jang, J.-H. Metal-carbonate formation from ammonia solution by addition of metal salts--An effective method for CO2 capture from landfill gas (LFG). Fuel Process. Technol. 2010, 91, 1500–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miltner, M.; Makaruk, A.; Harasek, M. Application of gas permeation for biogas upgrade—operational experiences of feeding biomethane into the austrian gas grid. In 16th European Biomass Conference & Exhibition From Research to Industry and Markets, Valencia, Spain, 2008.

- Nakken, T.; Eté, A. The wind/hydrogen demonstration system at Utsira in Norway: Evaluation of system performance using operational data and updated hydrogen energy system modeling tools. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2010, 35, 1841–1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prism Membrane Hydrogen Recovery & Purification. Available online: http://www.airproducts.com/products/Gases/supply-options/prism-membrane-hydrogen-recovery-and-purification.aspx (accessed on 16 October 2012).

- Brunetti, A.; Bernardo, P.; Drioli, E.; Barbieri, G. Membrane engineering: Progress and potentialities in gas separations. In Membrane Gas Separation; Yampolskii, Y., Freeman, B., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2010; pp. 279–312. [Google Scholar]

- Naturalhy. Available online: http://www.naturalhy.net/ (accessed on 16 October 2012).

- Grainger, D.; Hägg, M.-B. The recovery by carbon molecular sieve membranes of hydrogen transmitted in natural gas networks. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2008, 33, 2379–2388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebollar-Perez, G.; Carretier, E.; Lesage, N.; Moulin, P. Volatile organic compound (VOC) removal by vapor permeation at low voc concentrations: Laboratory scale results and modeling for scale up. Membranes 2011, 1, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Feng, X.; Lawless, D. Separation of gasoline vapor from nitrogen by hollow fiber composite membranes for VOC emission control. J. Membr. Sci. 2006, 271, 114–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumdar, S.; Bhaumik, D.; Sirkar, K.K. Performance of commercial-size plasmapolymerized PDMS-coated hollow fiber modules in removing VOCs from N2/air. J. Membr. Sci. 2003, 214, 323–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GKSS Home Page. Available online: http://www.hzg.de/ (accessed on 16 October 2012).

- MTR Home Page. Available online: http://www.mtrinc.com/ (accessed on 16 October 2012).

- The OPW VaporsaverTM system. Available online: http://www.opwglobal.com/ (accessed on 16 October 2012).

- Pattle, R.E. Production of electric power by mixing fresh and salt water in the hydroelectric pile. Nature 1954, 174, 660–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tofte prototype plant. Available online: http://www.statkraft.com/energy-sources/osmotic-power/prototype/ (accessed on 16 October 2012).

- Gerstandt, K.; Peinemann, K.-V.; Skilhagen, S.E.; Thorsen, T.; Holt, T. Membrane processes in energy supply for an osmotic power plant. Desalination 2008, 224, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2012 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

He, X.; Hägg, M.-B. Membranes for Environmentally Friendly Energy Processes. Membranes 2012, 2, 706-726. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes2040706

He X, Hägg M-B. Membranes for Environmentally Friendly Energy Processes. Membranes. 2012; 2(4):706-726. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes2040706

Chicago/Turabian StyleHe, Xuezhong, and May-Britt Hägg. 2012. "Membranes for Environmentally Friendly Energy Processes" Membranes 2, no. 4: 706-726. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes2040706