There is a peculiarity about the revision of historians that excludes them from the benefit of the common law that innocence must be assumed until guilt is proved. The presumption which is favourable to makers of history is adverse to writers of history. For history deals considerably with hanging matter, and nobody ought to hang on damaged testimony.

Acton

1. Introduction

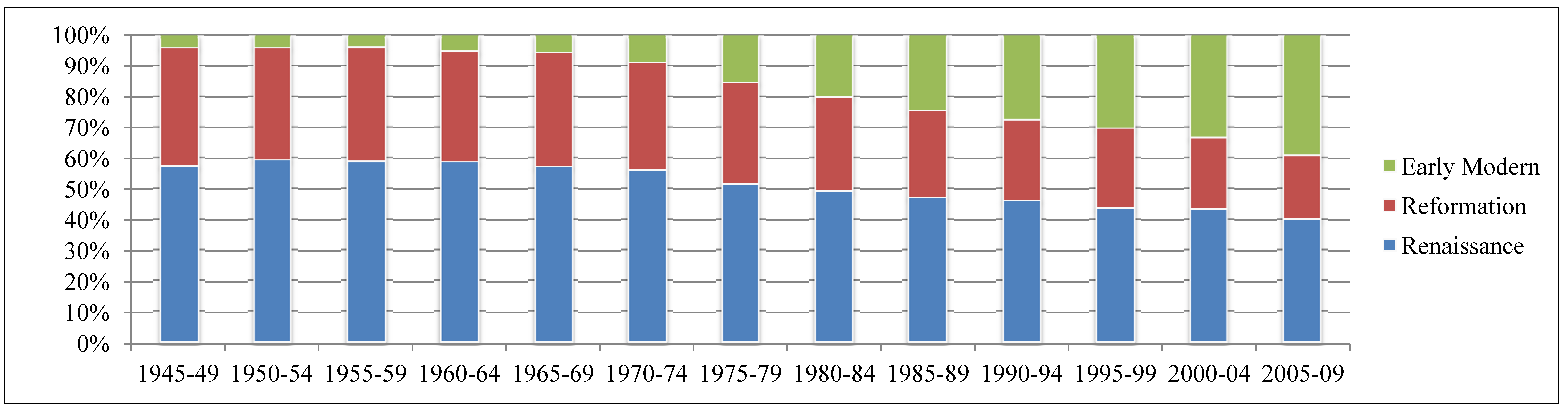

It seems that we cannot agree on what to call the history of Europe from roughly 1300–1600. We used to call it

Renaissance and

Reformation. Now we are not so certain what that means. Many among us would rather call it

early modern history.

1 This is more than merely giving a new label to a familiar thing. It is true, of course, that we can call a given thing by any word we please—but only if the thing is really given. There was an airline once called ValuJet. Then it ran into trouble. Now it is called AirTran.

2 That was a change in name that worked. But it is different with Renaissance and Reformation. The reason why some of us call Renaissance and Reformation

early modern history is that we do not know exactly what we mean by

Renaissance and

Reformation because it is precisely

not a given thing. But if it is not a given thing, it really does not help to change what we are calling it. We cannot even tell if we are merely changing labels or changing the subject, too. So far from being a matter of mere terminology, the change from

Renaissance and

Reformation to

early modern history reveals a basic truth about our state of mind: we are confused about the subject we are studying.

The purpose of this paper is twofold. In Sections two to five I will explain what seem to me to be the reasons why we are confused. They stem from the desire to turn history into a science. In Section six I will make three observations that seem to me to follow from that explanation. One is that there are valid reasons for the shift from Renaissance and Reformation to early modern history. Another is that the same reasons call for something different from that shift. The third is that Renaissance and Reformation confront us directly with the significance of disagreements dividing the living from the dead and the significance of grammar for treating such disagreements. That makes them very much worth keeping.

2. Agreement on Criteria

First, then, what is the source of the confusion? For an answer to this question I think it helps to reduce two familiar accounts of Renaissance and Reformation to a bare minimum. One was given by the people who lived through Renaissance and Reformation. It is embedded in the very terminology of

Renaissance (rebirth) and

Reformation (reform).

3 That terminology refers to some kind of revival of antiquity. It places the emphasis on what was or should have been the same in Renaissance and Reformation as in antiquity. The other was given in the nineteenth century, most famously by Jacob Burckhardt (1818–97) and Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770–1831). Burckhardt and Hegel viewed Renaissance and Reformation as the beginning of the modern world (see [

5,

6]). They stressed whatever was the same in Renaissance and Reformation as in modernity.

Once it is put like that, we seem to face a contradiction. On one account, Renaissance and Reformation revived antiquity; on the other, they ushered in modernity. That raises obvious questions: which of these two accounts is true and in which sense? Could both of them be true? What was the same in Renaissance and Reformation as in antiquity? What was the same as in modernity?

These are exciting questions. They constitute a great temptation to jump directly into the fray of evidence and argument. But the temptation needs to be resisted until we know the answer to a more basic question, namely, how can we even tell that anything is the same as anything else in history?

That question is more difficult to answer than it may seem. The most convincing answer I have found was given by Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889–1951). His answer works not just for history, but for any area of knowledge. It is that you can only tell that something is the same as something else if you have a criterion of identity, and a criterion of identity is something that you cannot have unless you speak a language and understand its grammar ([

7], pp. 24–25; [

8], nrs. 243–55, pp. 95

e–98

e).

4 Here

grammar means something different from syntax and morphology. It concerns the essence of what things are. It draws distinctions between things that infants do not know, and that we take for granted once we have mastered them as, for example, the distinctions between a color and a shape, a number and a sound, a memory and a dream, the present and the past, and "I" and "you." As Wittgenstein put it, "

essence is expressed in grammar" and "grammar tells what kind of object anything is" ([

8], nrs. 371 and 373, p. 123

e). If that is true, then without knowing grammar we cannot tell what kind of object

anything is, let alone whether it is the same kind as another. Apart from grammar, talk of identity is meaningless.

You cannot very well agree with Wittgenstein on this unless you throw out most of the conceptual baggage with which scholars and scientists have been traveling for centuries, including not a few who made the so-called linguistic turn. Needless to say, that is difficult to do and I do not propose to do it here.

5 But the point about identity itself is not particularly complicated to explain.

Take one of Wittgenstein's favorite examples: the sentence "it is 5 o'clock on the sun" ([

8], nrs. 350–1, pp. 118

e–19

e). On its face, that sentence looks like a straightforward statement of a certain fact. The meaning of the statement may not be exactly clear. But one thing seems to be certain: no matter what it means, it must be either true or false. Either it is 5 o'clock on the sun, or it is not. There seems to be no other possibility. The law of the excluded middle has to hold, no matter what we say.

This is what Wittgenstein denied. He asked, what does it mean to say, "it is 5 o'clock on the sun"? Someone might answer, "it means the same as 'it is 5 o'clock here on earth,' except that it is on the sun." That is an explanation by identity. It relies on the notion that something is the same as something else, namely, time on the sun as time on earth. But the explanation does not work. When we say, "it is 5 o'clock here," we know what we mean. We know because we know how to tell the time: by looking at a watch. Our watch is the criterion by which we tell what time it is. Our watch is not the only criterion that we could use, nor necessarily the most reliable. We can also use cellphones, radio announcements, computer clocks, the frequency with which some atoms oscillate, and the position of the sun of course. But the important point is this: regardless of which criterion we use, we know what "5 o'clock" means only because we have some criterion on which we are agreed.

That makes a criterion something radically different from data or evidence. It is neither a given fact nor something that you can observe. It is established by agreement, and the agreement is embedded in the language we have learned to speak. As Wittgenstein put it, "it is in their

language that human beings agree. This is agreement not in opinions, but rather in form of life" ([

8], nr. 241, p. 94

e). The criterion we use to tell the time of day is but one tiny and specific part of that agreement. Without such an agreement, we could have no criterion. Without such a criterion, we could not make sense of "5 o'clock."

That is precisely the condition in which we would find ourselves if someone were to say, "it is 5 o'clock on the sun." We would not know what sense to make of that expression. We have no criterion for the time of day on the sun. We have no idea what "5 o'clock on the sun" is supposed to mean—let alone whether it is the same as "5 o'clock on earth." There is no "same time" on the sun. If we say that "5 o'clock on the sun" means the same as "5 o'clock on earth, except that it is on the sun," we are not saying anything at all. We merely beg the question. We have not yet explained just what it is that is supposed to be the same. Until we do, the sentence "it is 5 o'clock on the sun" merely looks like a statement of some fact with an uncertain meaning. In reality it is no statement whatsoever. It is meaningless. You might as well say, "gobbledy is gook." And "gobbledy is gook" is just a funny sound. It does not amount to an assertion. It can be neither true nor false. It is not subject to the law of the excluded middle. The law of the excluded middle does not apply to funny sounds, no matter how closely they ape the appearance of a sentence.

3. Disagreements with the Dead

If Wittgenstein was right on this, and I believe he was, we have a problem in history that is quite different from the problems we generally say we have. The problems we generally say we have are two. One is to tell what happened in the past. The other is to understand the past in its own terms. But these problems are not as great as they are said to be. Solving them of course takes time and effort, and the effort may well fail. But that is true in every area of knowledge. It hardly makes history more difficult than chemistry or economics. We know a lot that happened in the past. We know that Caesar died. We know that medieval knights went on crusade. We know that the first cities were built a few thousand years ago. We know that until 1969 none of us had travelled to the moon. To doubt such knowledge, not for specific reasons in a specific context, but because the past is something of whose existence we cannot be completely sure because it is supposedly no longer present, is to abandon history for metaphysics.

The case is similar with understanding people in their own terms. If we have evidence and know their language, we have the means to understand the people. If we do not, we don't. It makes no difference whether the evidence and the language come from the present or the past. What makes a difference are the difficulty of the language and the evidence. Take Thomas Pynchon (b. 1937), for example. Last time I checked he was among the living. But I do not believe I understand him now or ever will, in his own terms or any other terms, as well as William Durant the Younger (ca. 1266–1330)—and this in spite of the fact that William Durant the Younger was a medieval bishop who died many centuries ago. Don't get me wrong. I love

Gravity's Rainbow (1973). But I find Durant's

Tractatus de modo generalis concilii celebrandi (

ca. 1310) much easier to follow (see [

16,

17,

18]).

The problem, in other words, is neither how to understand the people of the past in their own terms nor how to tell what happened. That can be done, up to a very reasonable point. The problem is that sometimes doing the one means not doing the other. Sometimes our understanding of the people whose history we are writing ends in a disagreement with those people about our understanding of what it was that happened.

We know what we can do where such a disagreement arises among the living. We distinguish between understanding what someone says and agreeing with someone that it is true. I have no trouble understanding people who say that history is bunk. But I do not agree with them. I say, "The past is very much worth knowing." I understand that in the view of some the world is run by a conspiracy of Jews. But I maintain that that is not the case. I say, "You are deluded. No such conspiracy exists." I understand the man who says that he defended a human being's right to life when he killed the abortionist. But I deny what he asserts. I say, "That is not what happened. What happened is that you committed murder." We have a disagreement about criteria of identity. We state our disagreement and then take it from there: we talk or fight; we solve our disagreement or we keep arguing; we agree to disagree or go our separate ways.

But what if we run into a disagreement with people in the past? And what if our disagreement does not divide us simply over the difference between the truth or falsity of one or another statement, but over the criteria we need in order to determine what our disagreement is about? How can we tell what people in the past were doing or what was happening to them if they were living, not on the sun, but on the historical equivalent of the sun: a place in time where our criteria for telling what is the same as something else did not exist? How do we manage that kind of disagreement? Shall we use the criteria on which we are agreed today? That would mean taking sides with the living and disagreeing with the dead. Shall we then use the criteria used by the people whose history we are writing? That would mean switching sides, but not solving the disagreement. In either case the disagreement stands. In either case it is uncertain just what the disagreement is about, and the uncertainty is threatening to leave us without anything to say or do.

4. The Problem for Historians

Disagreements dividing the living from the dead over criteria of judgment and identity, it seems to me, confront historians with their most fundamental problem. Happily the problem is never all-consuming. There is a lot that has not changed or changed only a little in the entire span of human history, from the beginning of the career of Homo sapiens down to the present day. We eat, we drink, we sleep, we dream, we laugh, we cry, we sing, we dance, we mate, we live, we die. We have that much in common with every human being who lived before our time.

That is by no means a small thing. It means that we are able to surmount the differences between the many different forms of life that have been taken up by different human beings at different times in different places as though they were so many different ways to play.

6 We can learn the different languages and understand the different forms of life. As Wittgenstein put it, there is a "system of reference by means of which we interpret an unknown language," and that system consists of "shared human behaviour" ([

8], nr. 206, p. 88

e). That is a happy teaching. If it were otherwise, there would be little for historians to do.

Unhappily for historians, our profession requires us to concentrate on change. We must confront the differences between the present and the past, including differences in criteria, judgments, language, and forms of life. We must not be content with taking past people at their word. We are obliged to figure out what was the case, even if it turns out to differ from the case past people thought it was, or that they lied. We cannot place responsibility for meeting that obligation on any evidence. The evidence can only teach us the terms that human beings were using in the past. It cannot teach us which terms we are supposed to use today. We have to choose those terms ourselves with every word we say. If we use no past terms, we dismiss whatever judgments the people of the past were making as though their judgments did not count. If we use no present terms—assuming that were possible—we could not even tell what counts as evidence today, let alone of what it is supposed to be the evidence.

We must therefore negotiate between the present and the past. Our relation to the past is dialectical: the past talks back. We are obliged to listen, and we must act accordingly. Sometimes we must dismiss past forms of thought and action as lying beyond the limits of, not our understanding, but our present agreement in a present form of life. Sometimes we must insist on present forms of thought and action with which the people of the past might never have agreed. We may not simply do as we are told. We have to draw a line where our agreement with the dead comes to an end. There are some games we cannot play. But we must also recognize and understand those forms of thought and action with which we disagree and render an account of our disagreement. Our knowledge

of the past has to include the differences by which we are divided

from the past. Excluding those differences from history would be absurd. Anachronism is our daily bread. Whichever way we turn, we find ourselves confronting disagreements between the living and the dead, not simply about the difference between true and false, but about different forms of life. There is no history without such disagreements. As Arnaldo Momigliano once put it in a memorable turn of phrase, "What history-writing without moral judgments would be is difficult for me to envisage, because I have not yet seen it" ([

21], p. 370). He just ought not to have limited his claim to judgments that are "moral" (cf. [

22], esp. pp. 403–5).

That, it seems to me, is the most basic difference between history and science. It constitutes a problem that scientists can pretty much ignore. Scientists are not obliged to bother with the terms in which past people spoke. They have disagreements with each other, not with the past. They study, not human beings, but the phenomena of nature—and nature does not talk back in any human language. Criteria that were used in the past are none of their concern—no more than magic, final causes, or phlogiston. Science ends where history begins. When scientists make statements about the past, as they most definitely do, they do so in terms on which they are presently agreed. They can forget the terms that were used in the past. They know what they are studying.

7 Historians do not enjoy that luxury. Sometimes they act as though they did. But when they do, the histories they write obliterate the most characteristically human kinds of change: change in criteria of judgment, change in language, and change in form of life.

5. The Source of the Confusion

That, I think, explains our confusion about Renaissance and Reformation. When we began to treat Renaissance and Reformation as periods in the history of Europe, we replaced what humanists and reformers had said about themselves with our judgments. We adopted criteria of identity they did not share. We did so because our form of life had changed. We recognized the change we made and looked for justification. We thought we found justification in the evidence. The evidence, we thought, allowed us to establish precisely what was the same in Renaissance and Reformation as in antiquity and in the modern age. But in so doing we forgot the difference between history and science. We treated the dead as though they were the same as us. We failed to heed the difference between criteria and evidence—between their form of life and ours. We did not notice that our evidence contained no reasons with which to justify our criteria or our form of life. We acted as though the evidence could do our job for us. We neglected our most interesting and most important task. No wonder we never got the knowledge that we sought.

What we got instead was information. We piled evidence on evidence, kept asking ever subtler and more specific questions, and multiplied the criteria with which to tell what is and what is not the same as something else in history. We never asked the question that needed to be answered first: how did they differ from ourselves, not simply in what they said and did, but in their agreement on the criteria that specified just what it was they said and did? Not having asked the question, we could not find the answer. The answers we did find gave us no satisfaction. Dissatisfied, we could not rest. Instead we have kept going in one and the same direction: more questions, more evidence, more information. The further we progressed, the less our answers meant. As we increased our knowledge of Renaissance and Reformation, we turned Renaissance and Reformation into seemingly useless terms. Instead of proving that Renaissance and Reformation were the same as antiquity or as modernity, or both, we cast increasing doubt on the possibility of knowing anything about the past at all. Instead of taking responsibility for our disagreements with the dead, we dismantled the agreements we had with each other.

Today we find ourselves divided into factions: those who keep insisting on studying Renaissance and Reformation and those who think those terms are vague or meaningless; those who believe we can know something about the past and those who believe that we cannot; those who look for facts and those who look for understanding; those who treat the dead as though they had never really been alive and those who treat them as though they had never really died; those who ignore the judgments made in stating facts and those who state no facts so as to make no judgments. Our information is superb, our understanding faint. We face a mountain of evidence, a riot of conflicting criteria, and profound uncertainty about the meaning and extent of our knowledge of the past. That is the price we pay for having practiced history as though it were a science. No wonder we are confused.

6. Saving Renaissance and Reformation

Now let me offer the observations that seem to me to follow from this argument. The first is that there is an excellent reason for the shift from calling our period Renaissance and Reformation to calling it early modern history. The reason is that we have looked for things in Renaissance and Reformation that are the same as things today—except, of course, that they took place in Renaissance and Reformation, that sun in time where we imagine things to be the same as here except that they are on the sun. Trying to find such things has landed us in a dead end.

I do not mean that things like that cannot be found. One can make a perfectly compelling case that things in Renaissance and Reformation were quite the same in this or that regard as things in antiquity or in the modern age or, for that matter, in any other age. I mean that making such a case reduces the human beings of the past to objects of scientific study. It amounts to treating the dead as though they had never been capable of speech. It does violence to them by ruling their judgments out of order, as if we had the right to say, "You did not know what you were doing, but we do, and we will tell you now." The desire to refrain from doing such violence, it seems to me, is the real source of the attraction of the shift to early modern history. That makes it a welcome change.

My second observation is that the change is not of the right kind. It is one thing to recognize that treating Renaissance and Reformation as the rebirth of antiquity or the beginning of the modern world can hardly be the thing to do. But it is quite another to acknowledge our disagreements with the dead.

Stanley Cavell has written that the search for shared criteria amounts to a claim to community ([

9], p. 20).

8 In searching for shared criteria in history, we thus lay claim to a community uniting the living with the dead. Precisely because it unites us with the dead, it challenges our humanity to the core. We cannot meet that challenge unless we take responsibility for our criteria. To state something as true about the past without taking responsibility for the criteria we use in doing so, or worse, to stop maintaining anything as true in the belief that the transience of our criteria gives us the freedom to stop using them, is to fail our responsibility as human beings both to ourselves and to the dead. That failure is the chief reason, I believe, why our knowledge of the past leaves us dissatisfied and why we can find no end to disagreements that put our sanity in doubt. It cannot be remedied simply by changing terms or turning one's attention to new subjects of investigation.

My third observation is that we may have a better chance of meeting our responsibility if we preserve the terminology of

Renaissance and

Reformation. The reason is that disagreements with the dead pose problems not only for historians. They pose problems for all human beings who try to maintain agreement in a shared form of life.

9 Among those human beings the people living in Europe during the times of Renaissance and Reformation deserve particular attention. For the intensity with which they tried to bring antiquity to life reveals nothing more clearly than the problems their disagreements with the dead posed to their form of life. That makes Renaissance and Reformation superb examples of the specific form those problems take and the specific manner in which they can be addressed.

The specific form those problems took consisted of a failure to recognize the disagreements dividing Europe from antiquity—not unlike the failure I have imputed to historians today. The continuity supposedly uniting Europe with antiquity, it seems to me, is a canard we owe to the confusion of history with science. What actually united Europe with antiquity was an ongoing dialectic of disagreements about the most fundamental questions that human beings face and that could never be concluded because Europe kept making it a point of pride to measure itself against the very antiquity from which it had long since departed—a departure nowhere more evident than in the growth of the vernaculars and in the transformation of Latin from a language spoken by ordinary people into the possession of a literate elite. That was a change in form of life.

The problems peaked when scholastic theologians, jurists, and philosophers claimed the ability to demonstrate the truth about the God of Christianity, the law of ancient Rome, and the philosophy of Aristotle with scientific certainty in terms no ancient would have recognized. They peaked because the scholastics never recognized the gulf dividing their thinking from the very ancient writings on whose authority they based themselves, and never took responsibility for the sheer novelty of the criteria on which they came to be agreed. Their confidence divided Europe into factions—via moderna and via antiqua, conciliarists and papalists, clergy and laity, Protestants and Catholics—fighting each other with increasing passion because they could not tell the difference between their disagreements with each other and their disagreements with the dead.

The specific manner in which those problems were addressed consisted of a turn from science to language. That turn was made by humanists and by reformers with very much the same resolve.

10 The significance historians of Renaissance and Reformation have long attributed to that turn thus is entirely deserved. But it is difficult to understand the full extent of that significance unless it is framed in the terms that Wittgenstein provided in the

Philosophical Investigations. In those terms "the

speaking of language is part of an activity, or of a form of life" [

8], nr. 23, p. 15

e) and "giving orders, asking questions, telling stories, having a chat, are as much a part of our natural history as walking, eating, drinking, playing" ([

8], nr. 25, p. 16

e). For "it is in their

language that human beings agree. This is agreement not in opinions, but rather in form of life" ([

8], nr. 241, p. 94

e).

In those terms language is more than a means of communication and nothing like a veil or screen dividing us from past or present reality. It rather is the essence of humanity, the practice that makes human beings human, a part of human nature. "What we are supplying," Wittgenstein said, "are really remarks on the natural history of human beings" ([

8], nr. 415, p. 132

e; cf. [

10], pp. 149–58, 237–87). The natural history he had in mind is not to be confused with what is commonly so called. So far from being founded on the distinctions that lend conceptual stability to natural history as it is usually understood—distinctions like those between mind and matter, culture and nature, language and reality—the natural history of human beings in Wittgenstein's sense has precisely the reverse relation to those conceptual distinctions: it furnishes the ground from which they draw their sense. It is analytically prior to all conceptual distinctions. It is therefore a matter of neither language nor reality, neither culture nor nature, neither mind nor matter. It is not scientific and cannot be based on evidence. It is the history of a form of life whose essence is the ability to speak. It is told in the form of grammatical remarks—remarks on language—because "

essence is expressed in grammar" ([

8], nr. 373, p. 123

e).

11 That makes the natural history of human beings one and the same with the history of language.

That is the kind of history, it seems to me, that Humanism sought to teach. Its subject matter was the language (the form of life) in which human beings are agreed and the nature (the essence) of human beings as expressed in grammar. Studia humanitatis is not a metaphor. When humanists studied grammar, rhetoric, poetry, history, and moral philosophy, they studied precisely what they said they did: humanity. They studied humanity in order to solve their disagreements with antiquity, not by rejecting the form of science to which they owed those disagreements, but by staking their claim on humanity properly understood, drawing firm boundaries round the terrain where science has the right to rule, and learning to distinguish their disagreements with each other from disagreements with antiquity.

On this understanding it is plain nonsense to conceive of Humanism in terms of the distinction between content and form. Humanism has no content

but matters of form: forms of speech, forms of language, forms of life, and forms of humanity.

12 It gives knowledge not of things but of their essence; not of data but of criteria; not of facts but of their meaning. To identify Humanism with a specific doctrine or a specific set of disciplines is to miss its significance.

13 To treat Humanism as the enemy or the successor of Scholasticism is to misunderstand the character of the distinction between the two and to ignore the great respect scholastic forms of knowledge continued to enjoy side-by-side Humanism well beyond Renaissance and Reformation (cf. [

37,

38,

39,

40]). Scholars who base their understanding of Humanism, not on the nature of humanity, but on the differences dividing humanists from other human beings betray a preoccupation with the distinctive qualities of scholars that does justice neither to the humanity of scholars nor that of the illiterate.

Humanism was precisely the right means to come to terms with the disagreements that peaked in scholastic thought and proved invulnerable to scholastic means of analysis. If it concerned itself with anything specific being said, or the specific language in which it was being said, then only because language cannot be used at all, much less used well or studied, except by saying something in some language, regardless of whether something is a matter of love or hate, peace or war, art or science, ethics or law, politics or religion, philosophy or theology, and regardless of whether the language is ancient or modern, classical or vernacular, poetry or prose. Humanism demonstrates the clarity with which its proponents understood that their disagreements with each other did not turn on the difference between true and false, but differences in language. It held out the hope of agreement in a form of life that could be shared by the literate and the illiterate alike, and that would let them express their disagreements with the dead with the respect the dead deserve.

That hope, it seems to me, united humanists with reformers in a cause that makes the differences between them seem marginal—until their hope was dashed. It explains why they devoted themselves to studying ancient languages and ancient ways of life with a degree of urgency that must seem baffling, if not completely incomprehensible, to anyone who does not recognize the ability to speak as the essence of humanity. When they said that they were bringing antiquity back to life, they were under no illusion that antiquity was something like a corpse that could have been resuscitated in the rude sense with which their purpose has sometimes been confused. So far from ignoring the differences dividing them from antiquity, they gave those differences much greater prominence than anyone had done before. If they did bring antiquity to life, they did so, not by forging some kind of magical identity but quite the opposite, by restoring antiquity to the standing of one of two different parties in the dialectical relation between the present and the past (cf. [

41,

42,

43,

44]). They understood what the ancients had known and the scholastics had forgotten: that the humanity of human beings unites them in the very act by which they take responsibility for differences dividing them from each other.

That strikes me as an outstanding reason to keep referring to the period as Renaissance and Reformation. The reason is not simply that Renaissance and Reformation reflect the understanding that humanists and reformers had of their place in time. Nor is it simply that Renaissance and Reformation flag the respect they had for antiquity. And least of all it is that Renaissance and Reformation have the authority of tradition. That early modern history is a newfangled way of speaking about the period is no good reason for rejecting it. Renaissance and Reformation themselves are terms that were newfangled once. Tradition, as the saying goes, consists of innovations that have worked.

What gives

Renaissance and

Reformation a great advantage over

early modern history is that they render a service, not to tradition or the past, but to ourselves. We call ourselves historians and we regard our discipline either as one of the humanities or as a social science more closely related to the humanities than social sciences like economics and sociology.

14 But our practice puts us at odds with humanists and reformers in Renaissance and Reformation. It rather makes us cousins of the scholastic theologians preceding them. Like our cousins, we are divided into conservatives who claim that our knowledge reflects reality because it is in fact reality we know (our

via antiqua) and critics who claim that reality lies irretrievably beyond our ken because our knowledge merely reflects the categories of our understanding (our

via moderna). Like our cousins, we have not grasped the role that disagreements with the dead play in our form of life and we hold language cheap. We lag behind the humanists and the reformers. We have not risen to the challenge our time poses to us as they did rise to theirs.

As far as I can tell, the turn to early modern history confirms that diagnosis. At best, it replaces disagreements historians once had about the end of the Middle Ages and the beginning of the Modern Age with disagreements about the beginning and the end of early modern history. At worst it prevents us from taking responsibility for our criteria of judgment and identity. By contrast Renaissance and Reformation bring us directly face to face with the significance of disagreements with the dead and the significance of grammar for treating those disagreements. Renaissance and Reformation do not tell us what that significance might be all by themselves. But they will not let us forget the cause uniting humanists and reformers. That makes them very much worth keeping.

7. Conclusions

Europe's relationship to antiquity can serve historians as a criterion with which to tell how Europe met the challenge the past gives all human beings all the time. At times Europe was confident of having met that challenge. At such times, Europe could well afford to focus its energies on science. Scholasticism, Enlightenment, and the nineteenth century come to mind. At other times Europe's confidence was shaken, Europe's agreements turned into faction, and Europe's disagreements with the dead demanded a kind of knowledge no science has on offer, regardless of whether the science is logical, mathematical, physical, or any other kind. At those times, grammar took precedence.

There may be no time in European history when disagreements with antiquity proved more difficult to manage than during Renaissance and Reformation—except perhaps the time when the Ottonians restored the Roman Empire and when the Pope, as St. Bernard once put it, transformed himself from the successor of St. Peter into the successor of Emperor Constantine.

15 And there may be no time when grammar was needed more urgently to understand what human beings share, what makes them different from each other, and what they are to do about their disagreements with the dead—except perhaps the time beginning when Wittgenstein was born.

16 Renaissance and Reformation were probably the last time when disagreements with antiquity posed the main challenge to Europe's agreement in form of life. The antiquity from which we find ourselves divided nowadays is no longer that of ancient Athens, Jerusalem, and Rome, but that of humanity as a whole, from its pre-hominid beginnings via the spread of Homo sapiens across the globe to the invention of urban and rural forms of settlement that used to typify most human life until as recently as only two centuries ago. The forms of life we have since then invented differ so deeply from all their predecessors that Europe itself is fast receding into antiquity. Our successors will have less reason to study ancient Athens, Jerusalem, and Rome than our predecessors did. But they will find it just as difficult to tell the difference between their disagreements with each other and their disagreements with the dead, and they will still need grammar to maintain their humanity.

It is a sobering thought that the attention humanists and reformers lavished on language was not enough to stop Europe from entering into civil wars that wreaked more havoc with Europe's agreement in form of life than anything had done before. On that score scholars who stress the differences dividing humanists from other human beings make an important point. Their point is proof of the grave difficulties that human beings face in learning how to exercise the faculty of speech without destroying the agreement—the humanity—they owe to that very faculty. Today those difficulties may well be greater than they have ever been before. That makes for an outstanding reason to keep studying the history of, not early modern Europe, but Renaissance and Reformation.