Virtual Pilgrimage and Virtual Geography: Power of Liao Miniature Pagodas (907-1125)

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Pagodas on the Pagoda

3. Miniaturizing Pilgrimage through Miniatures

- South Wall

- West Wall

- North Wall

- East Wall

- South Wall

- 1.

- Lumbinī (near the palace of King Śuddhodana)

- 2.

- Bodhgayā (where the Buddha gained awakening)

- West Wall

- 3.

- Sārnāth (where Deer Garden is located)

- 4.

- Śrāvastī (where Jetavana Garden is located)

- North Wall

- 5.

- Sānkāśya (where the Buddha descended the treasury stairs after giving a sermon to his mother in the Trāyastriṃśa Heaven)

- 6.

- Rājgir (where Vulture Peak is located)

- East Wall

- 7.

- Vaiśālī (where Mango Grove Garden is located)

- 8.

- Kuśnagara (where the Grove of Śāla Trees is located)

There are many evil and monstrous gusts of hot wind in this desert. Meeting [these gusts], all shall die and no one can survive. No birds flying above, and no animals running below. Looking everywhere one’s eyes can reach, searching for a route, one cannot know how to find a direction. Only old skeletons serve as signs of the route.44The Pamir Mountains have snow both in winter and summer. Also, there are poisonous dragons. If one crosses their will, they gush out poisonous wind with rain or snow as well as flying sand and pebbles. Meeting this catastrophic situation, not even one person out of ten thousand can survive. Locals therefore call [this area] ‘Snow Mountains’.45

4. Virtual Geography

Rub: You should know that not all people can visit the Holy Sepulcher of Our Dear Lord in Jerusalem, although many good people want to do that, and therefore many popes, cardinals, archbishops with the whole council have consented and confirmed that in churches and convents in all cities there shall be made a replica of the sepulcher of Our Lord. Good people should visit it daily in order to honor the Holy Sepulcher, as if they were in Jerusalem.65

If the large-scale replicas relate the Christian mythos of death and resurrection, the small-scale miniatures, through their sharp focus, serve to make this mythos mimetically present in ritual activity. In such a project, verisimilitude would constitute a distraction, overemphasizing the “then” and “there” of Jerusalem at the expense of the European “now” and “here”. … The more miniaturized and, ultimately, more stylized replicas of the Sepulchre (types III-V), along with their attendant ritual, sought to simulate the prototypical experience which lay behind the monument, thereby creating a utopia, a theatre of the mind and imagination, in which there was no distance because the specific locality in Jerusalem was, in the ritual process, erased.78

5. Bifold Replica

6. Ending Remarks

Conflicts of Interest

References

Primary Sources

Bada lingta fan zan 八大靈塔梵讚, T. 32, no. 1684.Dasheng bensheng xindi guan jing 大乘本生心地觀經. T. 3, no. 159.Foshuo Bada lingta minghu jing 佛說八大靈塔名號經, T. 32, no. 1685.Gaoseng Faxian zhuan 高僧法顯傳, T. 51, no. 2085.Song gaoseng zhuan 宋高僧傳, T. 50, no. 2061.Zhenyuan xinding shijiao mulu 貞元新定釋教目錄, T. 55, no. 2157.Secondary Sources

- Bentor, Yael. 1994. Tibetan Relic Classification. In Tibetan Studies: Proceeding of the 6th Seminar of the International Association for Tibetan Studies, Fagernes, 1992. Edited by Per Kvaerne. Oslo: Institute for Comparative Research in Human Culture, vol. 1, p. 24. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Shu (陳述), ed. 1982. Quan Liao wen. (全遼文). Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju, p. 159. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Xin. 2011. Miniature Buildings in the Liao (907–1125) and the Northern Song (960–1127) Periods. Ph.D. dissertation, Oxford University, Oxford, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Chou, Wen-shing. 2007. Ineffable Paths: Mapping Wutaishan in Qing Dynasty China. The Art Bulletin 89: 108–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Kyŏngmi (Joo, Kyeongmi 주경미). 2009. Yodae p’altaeyŏngt’ap tosang ŭi yŏn’gu (遼代 八大靈塔 圖像의 硏究). Chungang Asia yŏn’gu (중앙아시아연구) 14: 141–67. [Google Scholar]

- Connolly, Daniel K. 1999. Imagined Pilgrimage in the Itinerary Maps of Matthew Paris. The Art Bulletin 81: 598–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copp, Paul F. 2014. The Body Incantatory: Spells and the Ritual Imagination in Medieval Chinese Buddhism. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Crossley, Paul. 1988. Medieval Architecture and Meaning: The Limits of Iconography. Burlington Magazine 130: 116–21. [Google Scholar]

- Di Cosimo, Nicola. 2006. Liao History and Society. In Gilded Splendor: Treasures of China’s Liao Empire (907–1125). Edited by Hsueh-man Shen. New York: Asia Society, pp. 15–23. [Google Scholar]

- Gimello, Robert. 1994. Wu-t’ai Shan (五臺山) during the Early Chin Dynasty (金朝): The Testimony of Chu Pien (朱弁). Zhonghua fo xue xue bao (中華佛學學報) 7: 506–8. [Google Scholar]

- Hardison, O.B., Jr. 1965. Christian Rite and Christian Drama in the Middle Ages; Essays in the Origin and Early History of Modern Drama. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, pp. 173–75, 231–32. [Google Scholar]

- Huber, Toni. 2008. The Holy Land Reborn: Pilgrimage and the Tibetan Reinvention of Buddhist India. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, pp. 15–39. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Poksun (Kim, Bok-soon 김복순). 2007. Hyech’o ŭi Ch’ŏnch’uk sullye kwajŏng kwa mokchŏk (혜초의 천축순례 과정과 목적). Hanʼguk inmulsa yonʼgu (한국인문사연구) 8: 182–289. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Youn-mi. 2010. Eternal Ritual in an Infinite Cosmos: The Chaoyang North Pagoda (1043–1044). Ph.D. dissertation, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA; pp. 41–42. [Google Scholar]

- Krautheimer, Richard. 1942. Introduction to an ‘Iconography of Medieval Architecture’. Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 5: 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lévi-Strauss, Claude. 1966. The Savage Mind. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, pp. 23–25. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Yufeng (李宇峰). 1997. Liaoning Diqu Liaodai Gu Ta Fenbu yu Yanjiu (遼寧地區遼代古塔分布與研究). In Zhongguo Kaogu Jicheng: Dongbei Juan(中國考古集成: 華北卷). Edited by Jinji Sun (孫進己). Beijing: Beijing Chubanshe, pp. 1580–85. [Google Scholar]

- Liaoning-sheng wenwu kaogu yanjiusuo, (遼寧省文物考古硏究所), Chaoyang-shi Beita bowuguan, and (朝陽市北塔博物館), eds. 2007. Chaoyang Beita: Kaogu Fajue yu Weixiu Gongcheng Baogao (朝陽北塔: 考古發掘與維修工程報告). Beijing: Wenwu Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Wei-Cheng. 2014. Building a Sacred Mountain: The Buddhist Architecture of China’s Mount Wutai. Seattle and London: University of Washington Press, pp. 155–94. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Qian (劉謙). Xingcheng xian Baitayu ta (興城縣白塔峪塔). Liaoning dixue xuebao (遼寧大學學報) 4: 97.

- Liu, Shufen (劉淑芬). 1997. Jingchuang zhi xingzhi, xingzhi he laiyuan: Jingchuang yanjiu zhi er (經幢的形制, 性質和來源: 經幢研究之二). Zhongyang yanjiuyuan lishi yuyan yanjiusuo jikan (中央研究院歷史語言研究所集刊) 68: 643–786. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Shufen (劉淑芬). 2008. Miezui yu duwang: Foding zunsheng tuoluoni jingchuang zhi yanjiu (滅罪與度亡: 佛頂尊勝陀羅尼經幢之研究). Shanghai: Guji Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Moerman, D. Max. 2005. Localizing Paradise: Kumano Pilgrimage and the Religious Landscape of Premodern Japan. Cambridge: Harvard University Asia Center, pp. 82–83. [Google Scholar]

- Moerman, D. Max. 2010. Outward and Inward Journeys: An Introduction to Buddhist Pilgrimage. In Pilgrimage and Buddhist Art. Edited by Adriana Proser. New York: Asia Society, New Haven: Yale University Press, pp. 5–9. [Google Scholar]

- Nam, Tongsin (Nam, Dongsin 南東信). 2010. Hyech’o Wang o Ch’ŏnch’ukkuk chon ŭi palgyŏn kwa 8-dae t’ap (慧超 『往五天竺國傳』의 발견과 8대탑). Tongyang Sahak Yŏn’Gu (동양사학연구) 111: 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Rudy, Kathryn M. 2000. A Guide to Mental Pilgrimage: Paris, Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal Ms.212. Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte 63: 494–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudy, Kathryn M. 2011. Virtual Pilgrimages in the Convent: Imagining Jerusalem in the Late middle Ages. Turnhout: Brepols, p. 229. [Google Scholar]

- Sheingorn, Pamela. 1987. The Easter Sepulchre in England. Kalamazoo: Medieval Institute Publications, Western Michigan University, pp. 56–61. [Google Scholar]

- Hsueh-man, Shen. 2001. Realizing the Buddha’s Dharma Body: A Study of Liao Buddhist Relic Deposits. Artibus Asiae 61, no. 2: 291. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Jinbo (史金波). 1988. Xixia fojiao shilüe (西夏佛教史略). Yinchuan: Ningxia Renmin Chubanshe, pp. 118–19. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Jonathan Z. 1980. Constructing a Small Place. In Sacred Space: Shrine, City, Land. Edited by Benjamin Z. Kedar and Raphael J. Zwi Werblowsky. New York: New York University Press, pp. 18–31. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Jonathan Z. 1987. To Take Place: Toward Theory in Ritual. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, pp. 74–95. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Amy C., and Marianne E. Bergeron, eds. 2011. The Gods of Small Things. Pallas 86: 311–29.

- Sŏng, Sŏyŏng (成叙永), ed. 2012. Liao dai bada lingta de tuxiang tezheng yu shuxian Beijing (遼代八大靈塔的圖像特征與出現背景). In Liao Jin lishi yu Kaogu Guoji Xueshu Yantaohui Lunwenji (遼金歷史與考古國際學術研討會論文集). Shenyang: Liaoning Jiaoyu Chubanshe, p. 409. [Google Scholar]

- Sørensen, Henrik. 2011. Esoteric Buddhism under the Liao. In Esoteric Buddhism and the Tantras in East Asia. Edited by Charles Orzech, Henrik Sørensen and Richard Payne. Leiden and Boston: Brill, pp. 459–61. [Google Scholar]

- Steinhardt, Nancy Shatzman. 1997. Liao Architecture. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, pp. 391–95. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, Susan. 1993. On Longing: Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Takeshima, Takuichi (竹島卓一). 1944. Ryō Kin Jidai No Kenchiku to Sono Butsuzō. (遼金時代の建築と其佛像). Tokyo: Ryūbun Shokyoku, p. 206. [Google Scholar]

- Torii, Ryūzō (鳥居龍藏). 1937. Ryō no bunka o saguru (遼の文化を探る). Tokyo: Shōkasha, pp. 104–5. [Google Scholar]

- Wakiya, Kiken (脇谷撝謙). 1912. Ryō Kin Jidai No Bukkyō (遼金時代の佛教). Rokujō Gakuhō (六條學報) 126: 31–43. [Google Scholar]

- Kiken, Wakiya. 1913. Ryō-Kin bukkyō no chūshin (遼金佛教の中心). Rokujō Gakuhō 135: 2–9. [Google Scholar]

- Wittfogel, Karl A., and Chia-shêng Fêng. 1949. History of Chinese Society: Liao, 907–1125. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, Chuhyŏng (Rhi, Juhyung 李柱亨), ed. 2009. Tong Asia Kubŏpsŭng Kwa Indo ŭi Pulbyo Yujŏk (동아시아 구법승과 인도의 불교 유적). Seoul: Sahoe p’yŏngnon. [Google Scholar]

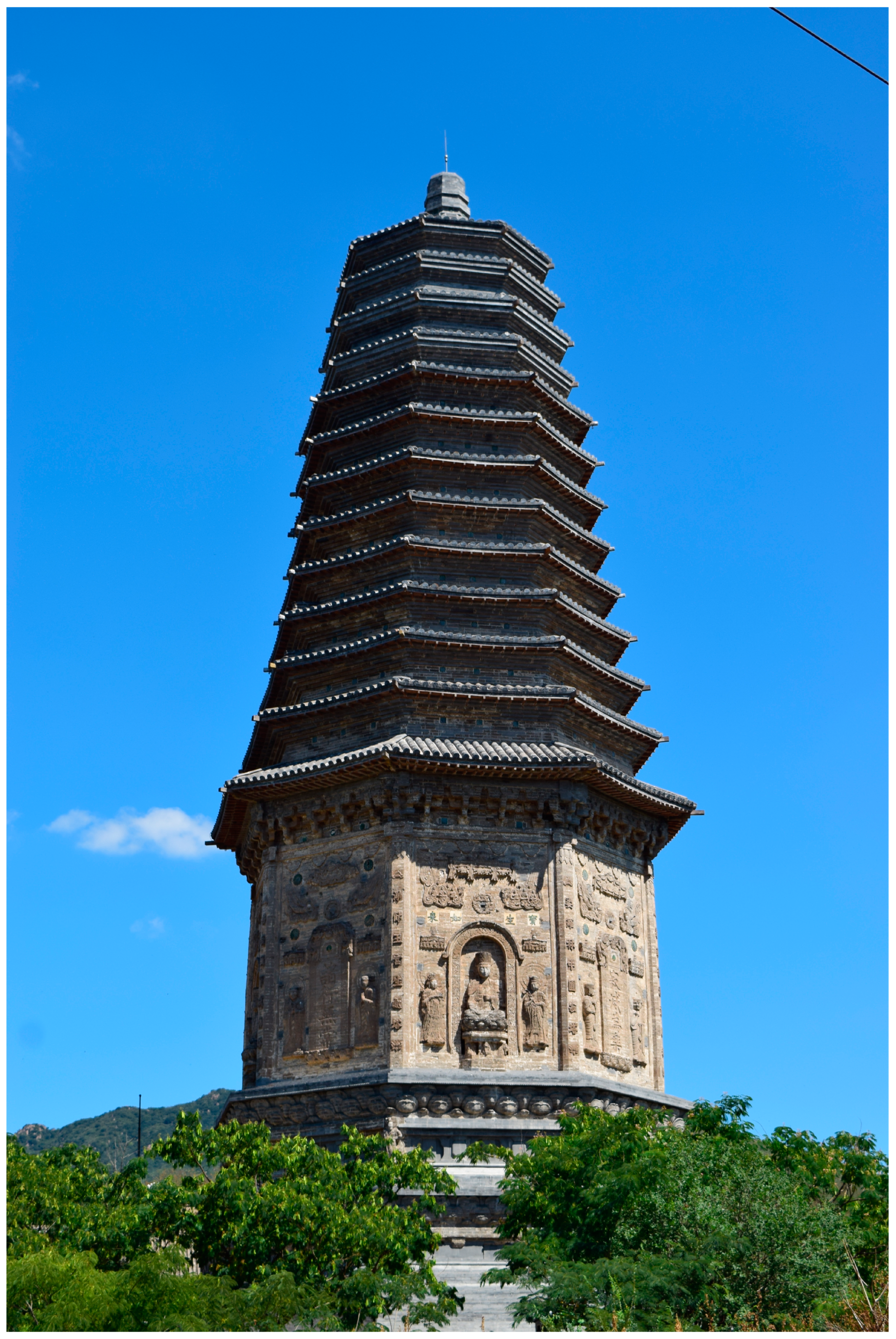

- Young, Karl. 1933. The Drama of the Medieval Church. Oxford: The Clarendon Press, vol. 2, pp. 500–13. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | For theoretical studies of the miniature, see (Stewart 1993; Lévi-Strauss 1966). For studies of miniatures in the material culture of the Mediterranean, see articles included in (Smith and Bergeron 2011). |

| 2 | The Liao had a keen interest in miniature architecture. For miniature buildings that were used as containers in Liao, such as coffins and reliquaries made in the shapes of architecture, see (Chen 2011). |

| 3 | As will be explained later, virtual pilgrimage was practiced by divergent religious traditions across the globe. I am grateful to Professor Jeffrey Hamburger for bringing my attention to the studies of virtual pilgrimage in the West. For a good monograph on virtual pilgrimage in medieval Europe, see (Rudy 2011). |

| 4 | For the Liao empire, see (Di Cosimo 2006; Wittfogel and Fêng 1949). |

| 5 | For example, the Yinshan Pagoda Forest (銀山塔林) in Pingchang昌平 district in the northeast of downtown Beijing has several Jin-dynasty pagodas adorned with miniature pagodas. |

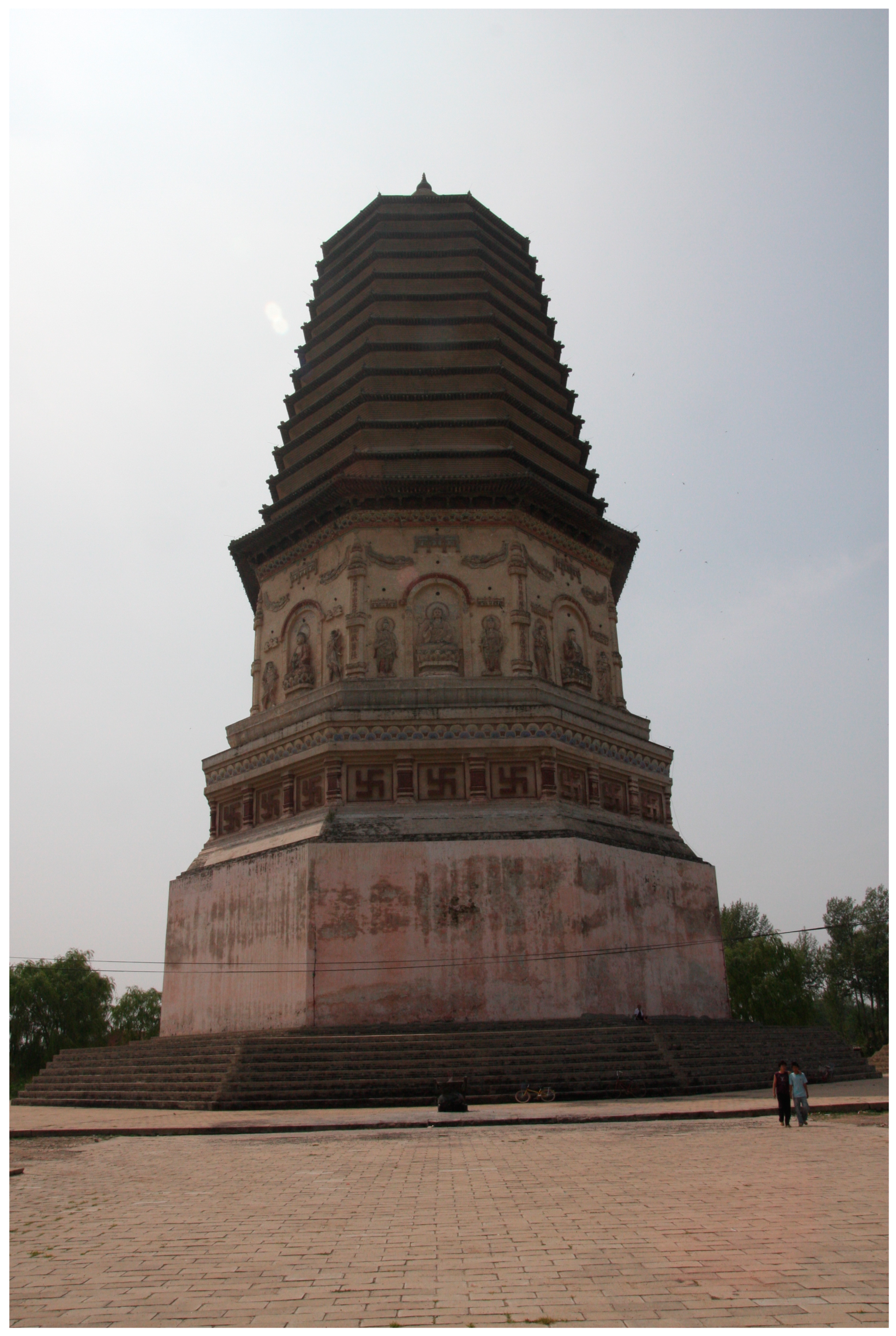

| 6 | The number of miniature pagodas placed on a Liao pagoda was typically eight. Some later Liao pagodas show modifications. One such example is Balengguan Pagoda 八棱觀塔, which has as many as 48 miniature pagoda reliefs attached to its pedestal and ground story walls. |

| 7 | The archaeological excavation was conducted from 1984 to 1996. For the most extensive report on this excavation, see (Liaoning-sheng wenwu kaogu yanjiusuo and Chaoyang-shi Beita bowuguan 2007). |

| 8 | Chaoyang is one of fourteen shi 市 (prefectural-level cities) that comprise Liaoning Province. A prefectural-level city is an administrative division of the People’s Republic of China that ranks below a province and above a county. |

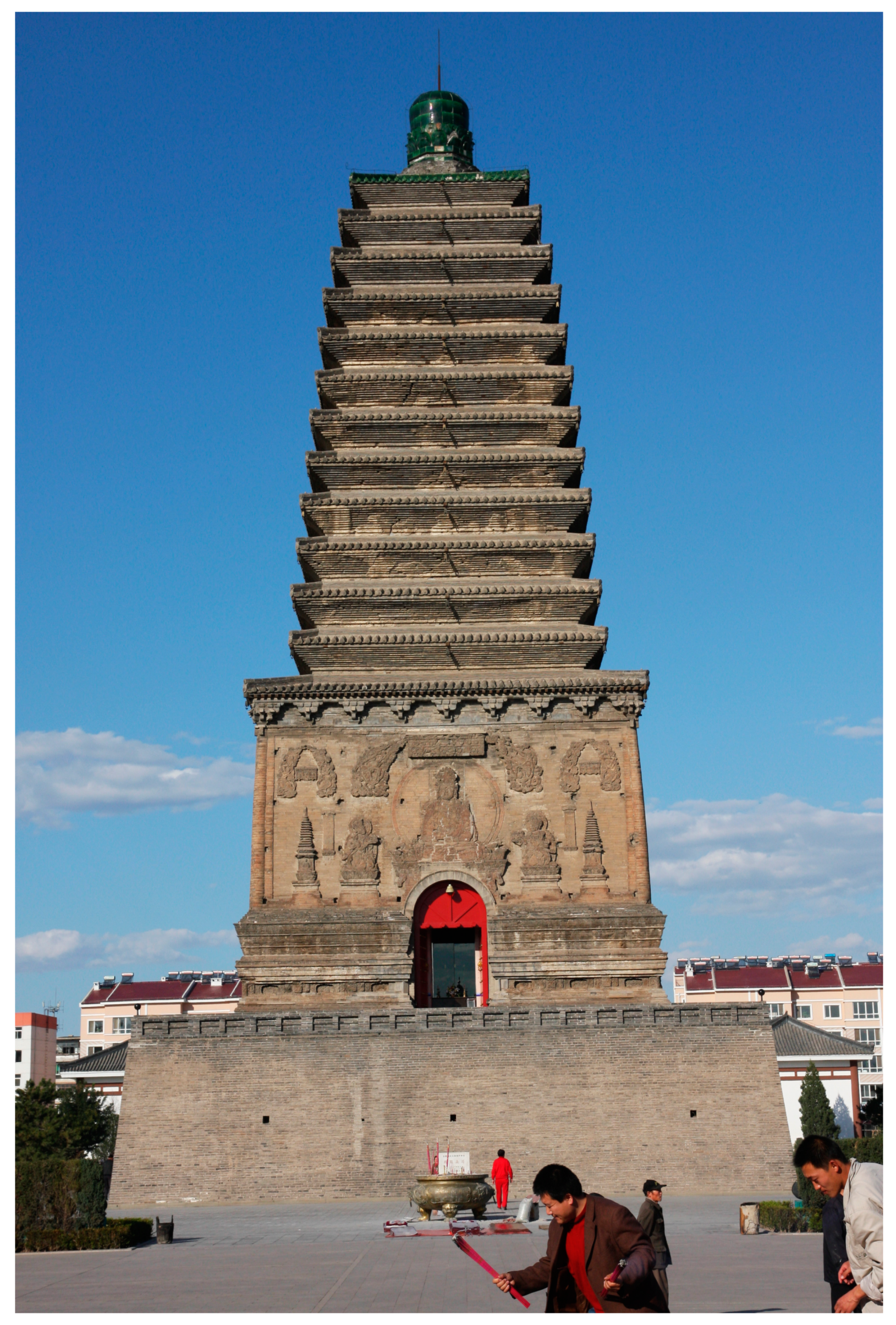

| 9 | Two are located in the downtown area (Chaoyang North Pagoda and Chaoyang South Pagoda 朝陽南塔); two are on Mount Fenghuang 鳳凰 near the downtown area (Yunjiesi Pagoda 雲接寺塔 [also known as Moyun Pagoda 摩雲塔] and Dabao Pagoda 大寶塔); and three are in suburban areas (Qingfeng Pagoda 靑峰塔 [also known as the Pagoda at Wushijiazi Village 五十家子塔], Balengguan Pagoda 八棱觀塔, and the southern pagoda of Shuangtasi 雙塔寺). Except for the latter two, all have a square plan. |

| 10 | Although the sculptures attached to Chaoyang South Pagoda’s ground story have not survived, the eight cartouches remaining on the ground story indicate the original presence of eight miniature pagodas. |

| 11 | The imagery on Chaoyang South Pagoda’s ground story did not survive, and this pagoda is difficult to date. the Some scholars have suggested that Chaoyang South Pagoda may predate Chaoyang North Pagoda, because a stone stele that dates to 984 (the second year of the Tonghe 統和 reign period) was discovered in 2004 from a nearby underground relic depository. It is, however, unclear whether this relic depository was related to Chaoyang South Pagoda because the depository was located roughly fifty meters to the north of this pagoda. A relic depository is usually found below or inside a pagoda. A complete excavation report regarding this relic depository, which was referred to as a ‘stone palace’ (shigong 石宮) in the stele inscription found in the depository, has yet to be published. A rubbing of the excavated stone stele was published in a pamphlet from the North Pagoda Museum, entitled Chaoyang fosheli 朝陽佛舍利. |

| 12 | |

| 13 | Early examples are seen in the canopies (large umbrellas) in the narrative panels (1st century BCE–1st century CE) from the Great Stupa at Sanci in India. |

| 14 | For the notion of “ritual of a ritual,” see (Smith 1980, p. 29). |

| 15 | Displacement is a key concept in Jonathan Z. Smith’s theory on the miniaturization of ritual. |

| 16 | This pagoda is also known as the Great Pagoda of the Middle Capital (中京大塔). |

| 17 | For a chart listing the cartouche inscriptions from these Liao pagodas, see Table 3 in Joo Kyeongmi’s paper (Chu 2009). |

| 18 | I first presented on the relationship between Chaoyang North Pagoda’s eight miniature pagodas and the Eight Great Sacred Places, and the virtual pilgrimage offered by miniature pagodas, in my paper “Buddhist Cosmology, Rituals and Mingling of the Buddha Bodies: Chaoyang North Pagoda” in The First International Heidelberg Colloquy on East Asian Art History held at University of Heidelberg in September 2006. The colloquy paper was based on my term paper for Eugene Wang’s graduate seminar “Sketch Conceptualism” in 2005. The papers I presented at The Map and the World: Representing Realms of Buddhist Thought conference at University of California (2007) and China’s Northern Frontier: Onsite Seminar, hosted by the Silk Road Foundation in July 2009, also discussed this topic. |

| 19 | The following cartouche inscriptions are from Chaoyang North Pagoda. The transcription of these inscriptions was first published in (Takeshima 1944). These cartouche are identical—differing only by a few sinographs—to cartouches found in the other four Liao pagodas. |

| 20 | 淨飯王宮生處塔. |

| 21 | 菩提樹下成佛塔. |

| 22 | 鹿野苑中法輪塔. |

| 23 | 給孤獨園名稱塔. |

| 24 | 曲女城邊寶堦塔. |

| 25 | 耆闍崛山般若塔. |

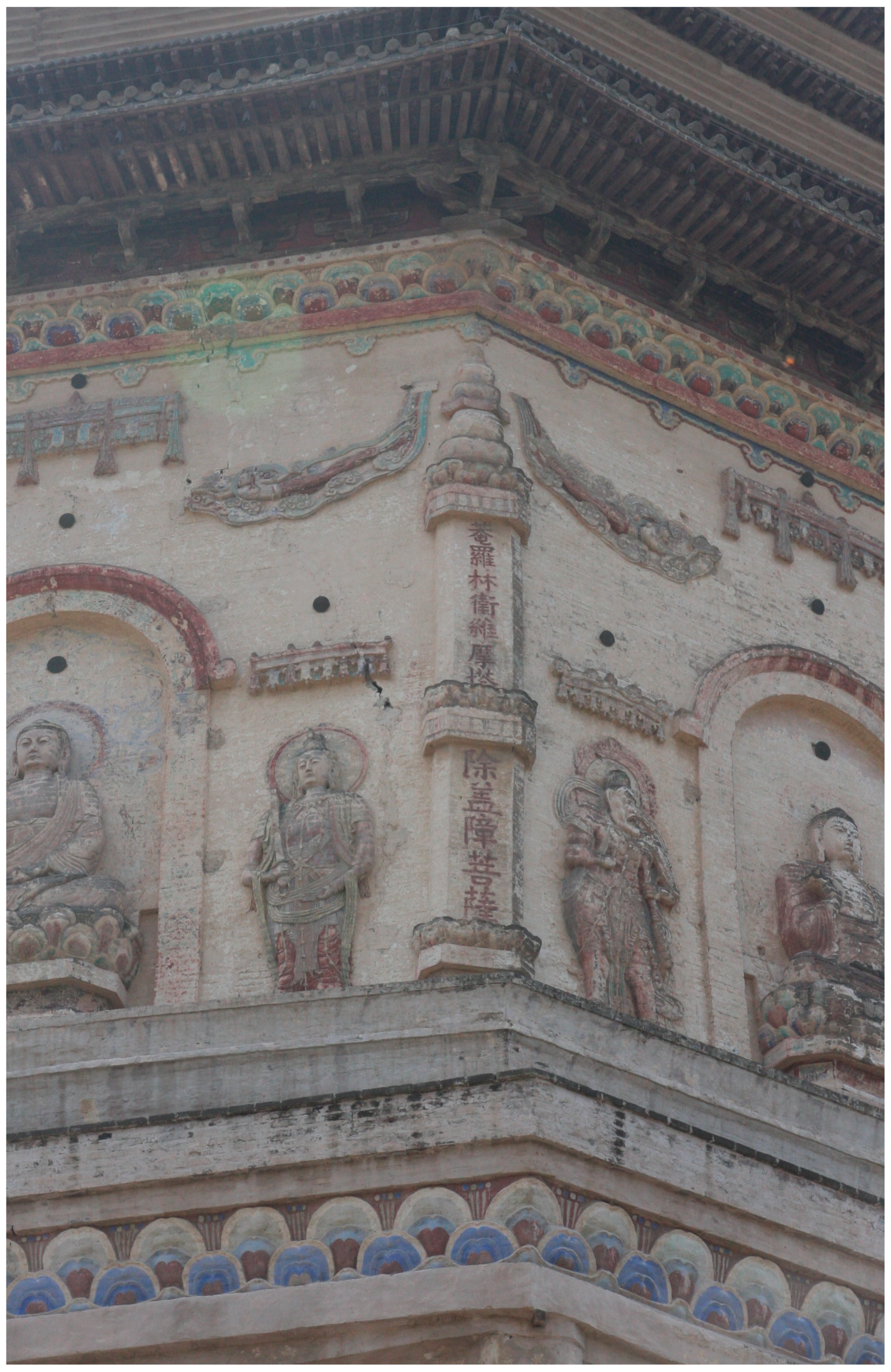

| 26 | 菴羅衛林維摩塔. Vimalakīrti, a wise Buddhist layman mentioned in the Vimalakīrti-nirdeśa-sūtra who had become an especially admired figure in the Chinese tradition, does not really mark an event in the life of the Buddha. As will be explained later, the Liao miniature pagodas’ cartouche inscriptions are citations from Dasheng bensheng xindi guan jing 大乘本生心地觀經 (T. 3, no. 159). This is a Buddhist sutra composed, partly or entirely, in China. Because this apocryphal sutra reflected Chinese modification of the events related to the Eight Great Sacred Places where the major life events of the Buddha took place, the Liao miniature pagodas that followed this apocryphal sutra came to mention this figure. For more on this, see (Chu 2009, pp. 146–51; Kim 2010, pp. 32–33). |

| 27 | 娑羅林中圓寂塔. The term yuanji 圓寂 in this inscription, literally meaning ‘perfect extinction,’ denotes the Buddha’s demise, which was the moment he entered parinirvāṇa (great nirvāṇa). |

| 28 | King Śuddhodana’s palace was located in Kapilavastu, and his wife, Queen Māyā, gave birth to Śākyamuni in Lumbinī on her way from this palace to her hometown. At present, the location of Kapilavastu is inferred to be either present-day Piprahwa or Tilaura-kot, both located in the border area between Nepal and India. Tilaura-kot is approximately 23 km to the northwest of Lumbinī and Piprahwa is to the southwest of Lumbinī. (Yi 2009, pp. 314–18). |

| 29 | Dasheng bensheng xindi guan jing, T. 3, no. 159. The first group of scholars who studied the Liao pagodas was Japanese archaeologists who explored historical monuments in Manchuria during the Japanese occupation of northeast China. In the 1930s, Torii Ryūzō, a Japanese archaeologist, anthropologist and folklorist, first found this textual source for the Liao miniature pagoda cartouches. For example, in his 1937 monograph that summarizes his two field trips to Northeast China and Mongolia, he briefly mentioned that the names of the Liao miniature pagodas came from the Mind Ground Sutra. See (Torii 1937). This textual source was also mentioned in more recently publications, including (Shen 2001; Sŏng 2012; Chu 2009, pp. 141–67). |

| 30 | Dasheng bensheng xindi guan jing, T. 3, no. 159:294a24-b7, 296a15-18. |

| 31 | The verse lines from the Mind Ground Sutra reads: 淨飯王宮生處塔 菩提樹下成佛塔 鹿野園中法輪塔 給孤獨園名稱塔 曲女城邊寶階塔 耆闍崛山般若塔 菴羅衛林維摩塔 娑羅林中圓寂塔。T. 3, no. 159:294a-b, 296a15-18. The Liao cartouche inscriptions exactly match these verse lines, except for a few sinographs. For example, Chaoyang North Pagoda’s cartouches use yuan 苑 instead of yuan 園 in its third cartouche, and jie堦 instead of jie 階 in its fifth cartouche. In both cases, the substituted sinograph has a meaning that is basically interchangeable with the original sinograph in the sutra, and therefore does not produce any difference in terms of meaning. Only the fourth and fifth cartouche inscriptions on Daming Pagoda in Ningcheng show minor but recognizable deviation from the original sutra verse. |

| 32 | Luohanyuan Bada lingta ji 羅漢院八大靈塔記。For the original text of this inscription, see (Chen 1982). The actual stele does not survive, but its rubbing preserves its entire inscription. Hsueh-man Shen suggests that the Liao eight pagodas are “a sign of the Buddha preaching the Law, thus a sign of the presence of the Buddhist Law,” because this inscription explains that these pagodas appeared when the Buddha’s preaching. Shen, “Realizing the Buddha’s Dharma Body,” 291. |

| 33 | Foshuo Bada lingta minghu jing 佛說八大靈塔名號經, T. 32, no. 1685:773a1–773b13; and Bada lingta fan zan 八大靈塔梵讚, T. 32, no. 1684:772b6–772c22. |

| 34 | Toni Huber has argued that these eight places and their stupas were not treated as a set of pilgrimage sites before the twentieth century. According to him, the concept of the eight great places as a distinctive group of pilgrimage destinations was gradually invented by archaeologists and art historians beginning in the early twentieth century, primarily based on an incorrect interpretation of Pala period stone steles that represented the eight major events of the Buddha’s life. He maintains that these places and pagodas were never recommended as destinations for actual pilgrimage or objects for direct encounter in surviving Chinese and Tibetan texts, which were probably translations of Indian texts written during the Pāla period. These texts instead describe these eight places and pagodas as objects of commemoration or general worship (pūja). See (Huber 2008). Huber correctly argues that the importance of the Eight Great Sacred Places as pilgrimage sites has been overemphasized in modern times, and that they were not as prominent a pilgrimage destination in premodern times as today. Travelogues of East Asian monks, however, suggest that a complete negation of the concept of the Eight Great Sacred Places as a pilgrimage destination in pre-modern times would be too extreme a view. |

| 35 | For a comprehensive and thorough study of East Asian monks who made a pilgrimage to India from the third to eleventh centuries, see (Yi 2009). |

| 36 | For a good study on the development of the eight pagodas as pilgrimage destinations in East Asia, see (Chu 2009, pp. 144–51). |

| 37 | In addition to these three East Asian monks, the famous Indian monk Vajrabodhi (Jingangzhi 金剛智, 671–741), who transmitted Esoteric Buddhism to Tang China, was also recorded to have “visited and venerated the pagodas of the Buddha’s eight phases of life.” 遂辭師龍智卻還中天 尋禮如來八相靈塔。Zhenyuan xinding shijiao mulu 貞元新定釋教目錄, T. 55, no. 2157:875b14. |

| 38 | For the biography of the monk Muru, see Song gaoseng zhuan 宋高僧傳, T. 50, no. 2061:846a24-c12. The Song Biographies of Eminent Monks was compiled by the Song dynasty monk Zanning 贊寧 (919–1002). For more on this monk, see (Yi 2009, p. 145). |

| 39 | 欲遊五竺禮佛八塔。Song gaoseng zhuan, T. 50, no. 2061:846a28. |

| 40 | I am grateful to Jason Neelis for explaining to me the political situation of the Pamir Mountains in the mid-eighth century. |

| 41 | Only fragments of the monk Wukong’s travelogue (Wukong ru Zhu ji 悟空入竺記) survive as quotations in the eighth-century monk Yuanzhao’s 圓照 prologue to Scripture on the Ten Powers Preached by the Buddha (Foshuo shili jing 佛說十力經) translated in 790 by the Kuchan monk Utpalavīry. Foshuo shili jing T. 17, no. 780:715c–717c. For more on this travelogue, see (Yi 2009, pp. 15–41, passim; Chu 2009, p. 146; Kim 2010, pp. 41-42). Several scholars pointed out that the ultimate goal of Hyech’o’s pilgrimage, as implied in his travelogue Wang o Ch’ŏnch’ukkuk chon 往五天竺國傳, was none other than the veneration of the eight pagodas. I am grateful to Professor Nam Dongsin for bringing Hyech’o’s case to my attention. (Nam 2010; Kim 2007). |

| 42 | The Taishō Buddhist canon includes many biographies of Chinese monks who died on their way to India. |

| 43 | Records of the Buddhist Kingdoms (Foguo ji佛國記) is also known as Biography of the Eminent Monk Faxian (Gaoseng Faxian zhuan高僧法顯傳). For the original text, see Gaoseng Faxian zhuan, T. 51, no. 2085: 857a-866c. |

| 44 | Gaoseng Faxian zhuan, T. 51, no. 2085: 857a16–18. |

| 45 | Gaoseng Faxian zhuan, T. 51, no. 2085: 857c26–28. |

| 46 | |

| 47 | A good example is dhāraṇī, a shortened version of a Buddhist sutra. As a dhāraṇī is a miniature of a sacred text, they were later believed to be powerful incantation. |

| 48 | For more on this, see (Rudy 2000). |

| 49 | For more on Kanezane’s virtual pilgrimage, see (Moerman 2005); and (Moerman 2010, p. 7). |

| 50 | For more on the displacement of ritual practice into writing as observed in the Greek Magical Papyri, see (Smith 1980, pp. 28–29). |

| 51 | Even life-size sculpture, in this sense, can be understood as a miniature, since it has lost the sensory dimensions of the original, including smell, sound, texture, color, as well as the temporal dimension. See (Lévi-Strauss 1966, pp. 23–25). |

| 52 | |

| 53 | |

| 54 | Miniature replicas of the Holy Sepulcher served as the setting for a complex new Christian ritual in Western Europe. The ritual was composed of four parts: the imitation and re-enactment of Christ’s Burial, the Easter Vigil, the Resurrection, and the Visit to the Tomb. Also, it involved the highly theatrical entombment and retrieval of symbols of Christ, such as the cross or the wafer, and then, at a later date, sometimes a statue of the dead Christ. For more on this ritual, see (Smith 1980, p. 23; Sheingorn 1987). For theater historians’ studies of the miniature replica of the Holy Sepulcher as the precursor to the European stage, see (Young 1933; Hardison 1965). |

| 55 | Tibetan Buddhists constructed architectural replicas of the Indian eight stupas. (Bentor 1994). |

| 56 | |

| 57 | |

| 58 | For an excellent study of this topic, see (Ibid., pp. 5–9). |

| 59 | Gaoseng zhuan. T. 50, no. 2059:358b. |

| 60 | Gaoseng zhuan. T2059, 50:358b8-14. Compilation of these biographies was completed in 519 by the monk Huijiao 慧皎 (497–554). |

| 61 | Meanwhile, the Xixia kingdom, after losing their access to Mount Wutai in the 1040s due to their estranged political relationship with Song, had copies of Mount Wutai’s famous Buddhist monasteries built on Mount Helan 賀蘭 in their kingdom so as to create a new sacred mountain. (Shi 1988), 156: requoted from Gimello, “Wu-t'ai Shan 五臺山 during the Early Chin Dynasty,” 507. And the sacred mountain was also recreated through cave temple murals and maps (Lin 2014). |

| 62 | |

| 63 | For more on Liao imperial patronage of Buddhism, see (Wittfogel and Fêng 1949, pp. 291–306). |

| 64 | Previous scholarship on replicas of the Holy Sepulcher by a number of scholars, including architectural historian Richard Krautheimer, have revealed the ways in which these replicas succeeded in transplanting and reproducing a holy place. For example, see (Krautheimer 1942; Crossley 1988). I am grateful to Professors Jeffrey Hamburger and Karl Whittington for introducing me to this scholarship. |

| 65 | Brussels, Koninklijke Bibliotheek Albert I, II 6907, manuscript copied after 1503. Translation from (Rudy 2011, p. 229). Italics mine. |

| 66 | On the development of the copies of the Holy Sepulcher, see (Sheingorn 1987, pp. 6–25). |

| 67 | |

| 68 | |

| 69 | For the five types of replicas of the Church of the Holy Sepulcher, see (Smith 1980, pp. 20–24). For the small-scale replicas of the Holy Sepulcher, see (Sheingorn 1987, pp. 33–42). |

| 70 | |

| 71 | |

| 72 | |

| 73 | |

| 74 | I thank Katherine Tsiang for pointing out that a similar shape was also used for commercial signboards in the Song dynasty. It seems this widespread motif in Buddhist art was transmitted to commercial signboards. |

| 75 | Baitayu Pagoda (also called ‘Jiulongyan Pagoda’ 九龍煙塔), simply meaning ‘the pagoda of the white pagoda valley’ is a modern name of this pagoda. An inscription found inside the pagoda’s underground relic deposit in 1972 records that the pagoda was called the Pagoda at Wuji Temple on Mount Kongtong (空通山悟寂院舍利塔) and was built in 1092. For more on this inscription, see (Liu 1983). |

| 76 | |

| 77 | |

| 78 | |

| 79 | Chaoyang North Pagoda’s modern finial bit resembles the finial of the Liao pagoda in Tianningsi天宁寺, Beijing. The latter, however, was the result of modern restoration as well. Tianningsi’s pagoda itself was heavily restored during the Ming and Qing (1644–1912) periods. |

| 80 | The original finial of this pagoda is at the Balin Right Banner Museum, and the current reproduction of the pagoda’s finial followed its original form. |

| 81 | The last two miniature pagodas, which mark Vaiśālī and Kuśinagara, have an image of Vimalakīrti and a reclining Buddha, respectively, emphasizing the narratives that each of the pagodas commemorate. These images do not appear on the eight miniature pagodas on the other Liao miniature pagodas in the Chaoyang area. |

| 82 | Compared to those of the Yunjiesi Pagoda, the sculptures of Chaoyang North Pagoda are more elaborate but flatter, and the lotus pedestal of the pagoda is more abstract. The Yunjiesi Pagoda has not yet been excavated, and it is not yet known whether it pre- or postdates Chaoyang North Pagoda. |

| 83 | The incantation pillars—stone pillar inscribed with dhāraṇī, or Buddhist “incantation” —began to gain popularity in the Tang dynasty and proliferated in Liao. These incantation pillars are normally octagonal and topped with a stone that imitates an East Asian tiled roof. In the medieval Chinese categories for Buddhist monuments, the distinction between the incantation pillar and the pagoda was often nebulous, and the former was often thought to be one type of pagoda. For more on the incantation pillar, see (Copp 2014; Liu 1997, 2008). |

| 84 | Although this unique case seems to reflect a drastic change for the eight pagodas, the eight pagodas were already represented as a single-story dhāraṇī pillar inside the Chaoyang North Pagoda as shown above. |

© 2017 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, Y.-m. Virtual Pilgrimage and Virtual Geography: Power of Liao Miniature Pagodas (907-1125). Religions 2017, 8, 206. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel8100206

Kim Y-m. Virtual Pilgrimage and Virtual Geography: Power of Liao Miniature Pagodas (907-1125). Religions. 2017; 8(10):206. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel8100206

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Youn-mi. 2017. "Virtual Pilgrimage and Virtual Geography: Power of Liao Miniature Pagodas (907-1125)" Religions 8, no. 10: 206. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel8100206