Identifying Ingrained Historical Cognitive Biases Influencing Contemporary Pastoral Responses Depriving Suicide-Bereaved People of Essential Protective Factors

Abstract

:1. Introduction

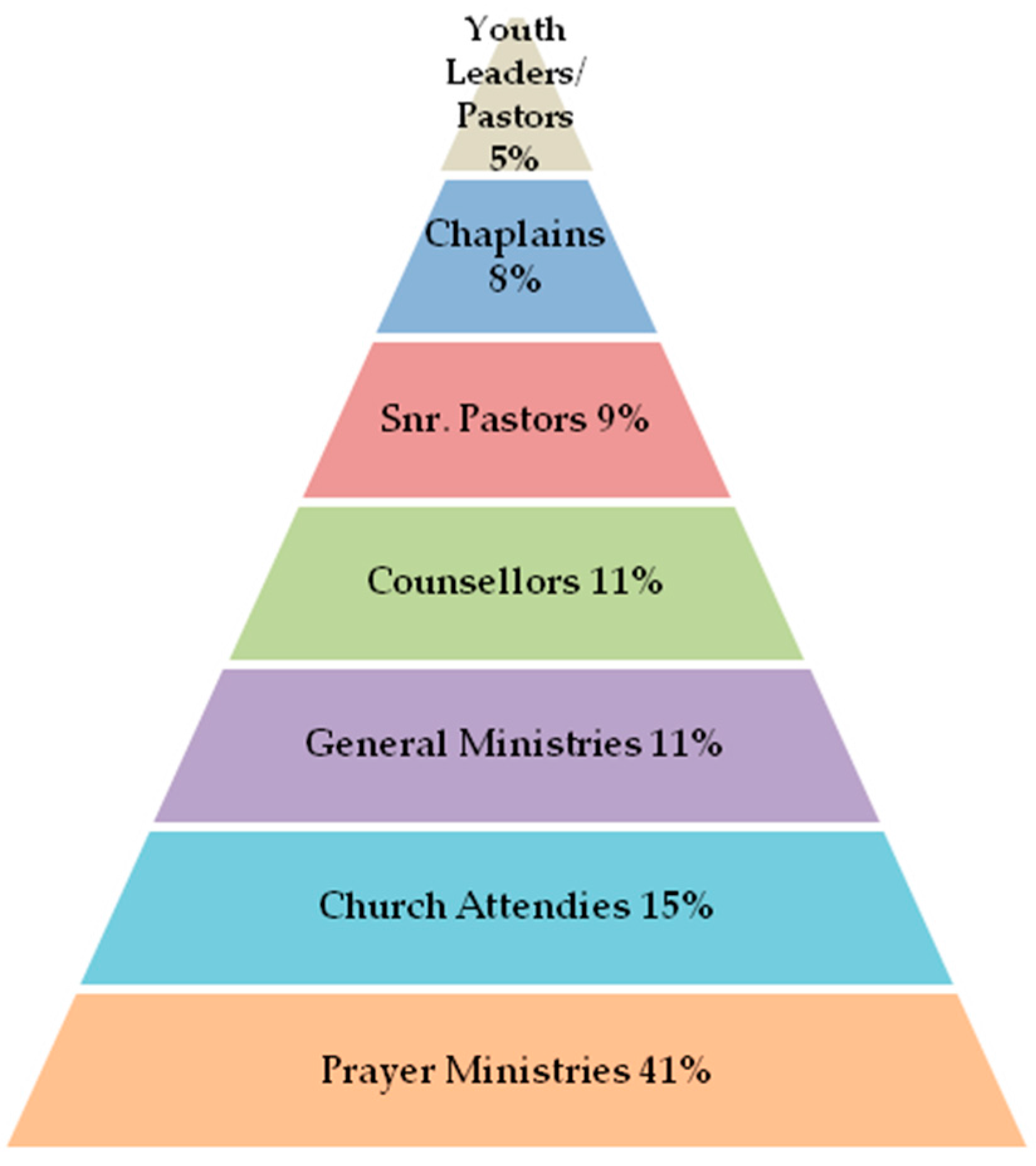

2. Methods and Materials

- -

- Session 1. Historical & Theological Issues to Suicide;

- -

- Session 2. Identifying Biological, Psychological & Socio-Cultural Issues in Suicide & Self-Harm;

- -

- Session 3. Postvention: Caring for Those Bereaved by Suicide;

- -

- Session 4. Practical Tools; and

- -

- Session 5. Challenges to Caregivers.

3. Analysis

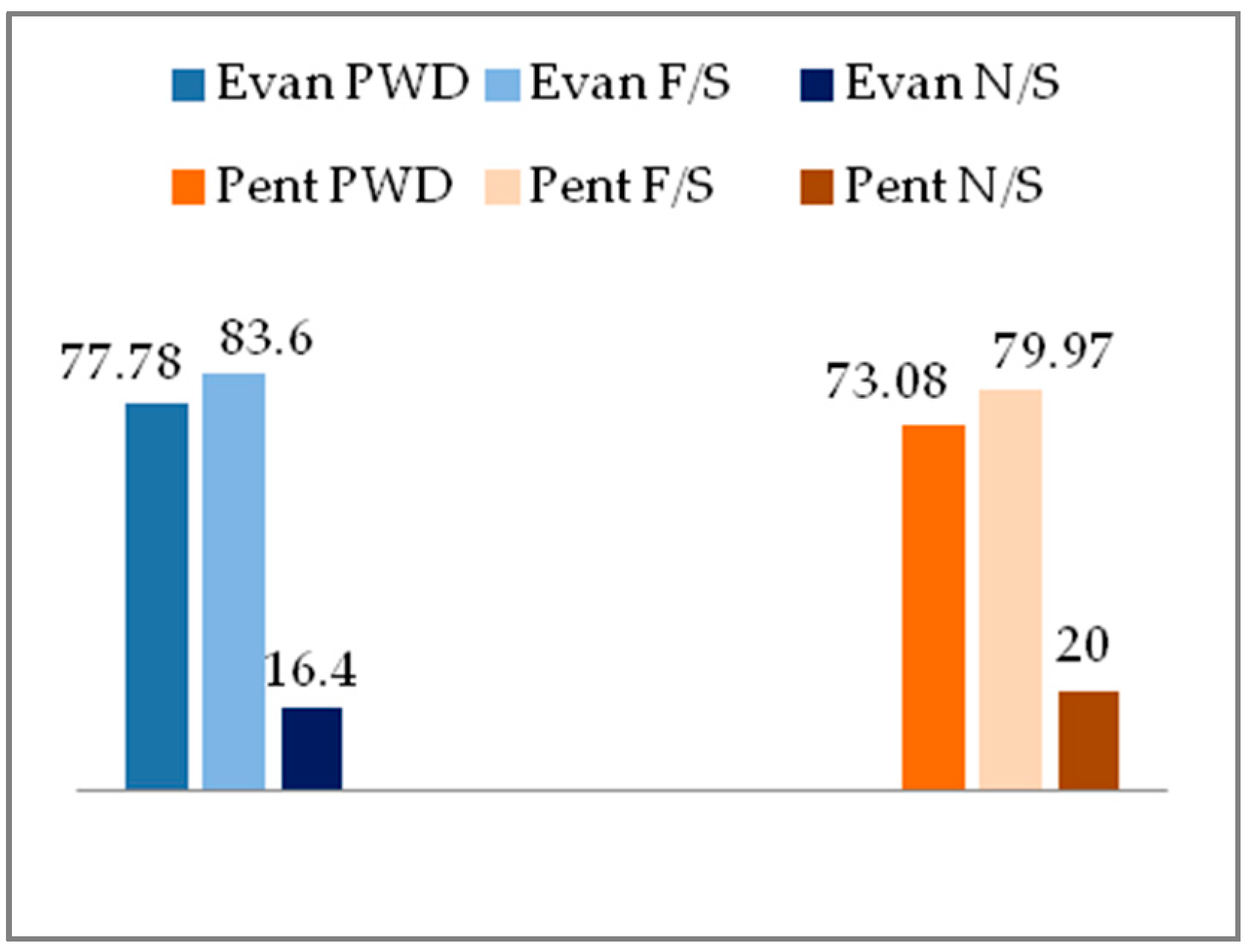

4. Results

- -

- Evangelical streams (E/S) noted an overall average 5.82% increase from PWD of 77.78% to 83.60%.

- -

- Pentecostal streams (P/S) noted an overall average 6.89% increase from PWD of 73.08% to 79.97%.

- -

- There was a greater N/S average of 3.6% toward favourable alternatives by P/S (20%) versus E/S (16.40%). These for reasons unknown did not adjust their view. The overall average percentage F/S in both streams was over 75%.

- -

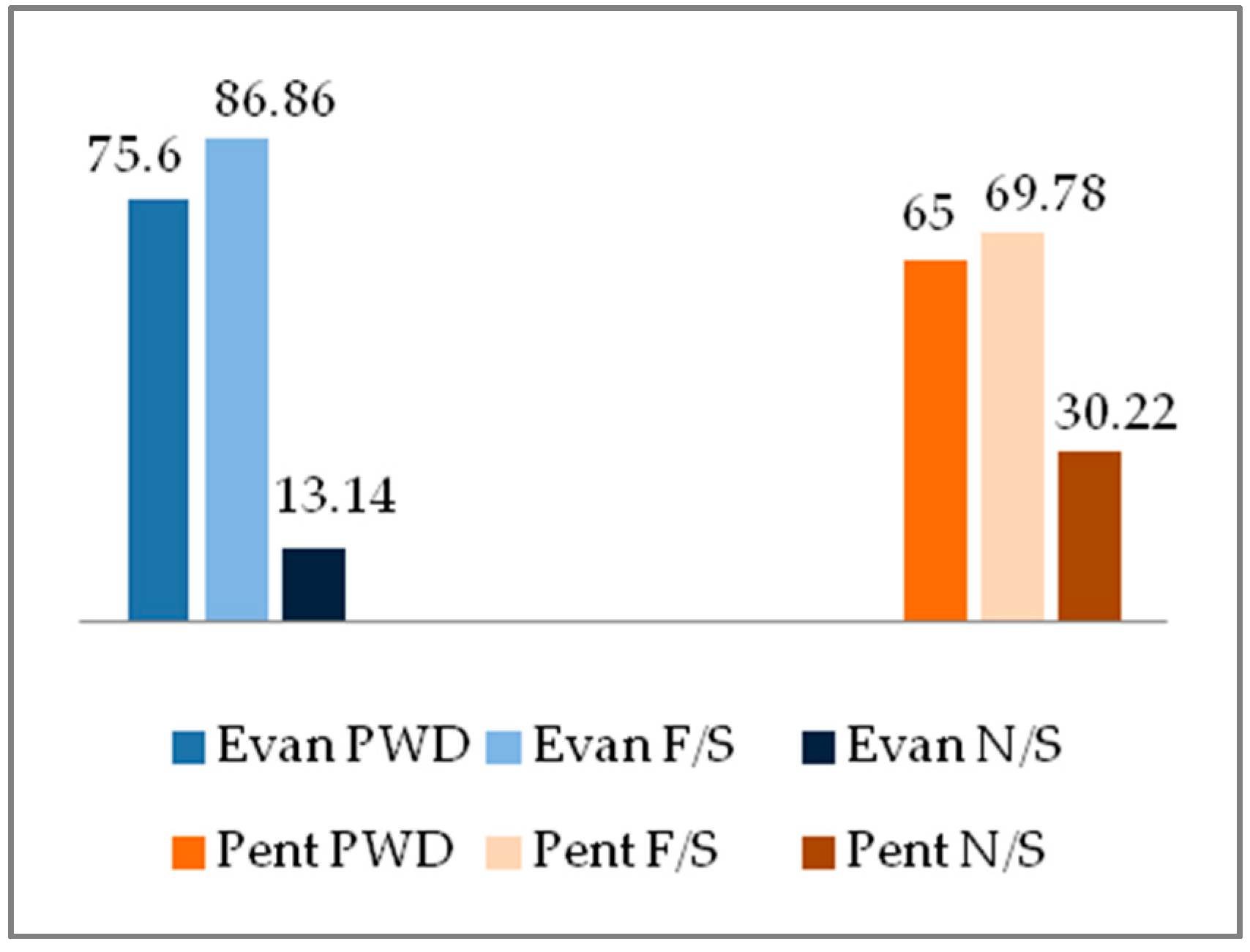

- E/S saw an overall average of 11.26% increase from PWD of 75.60% to 86.86%.

- -

- P/S had an overall average increase of 4.78% from PWD of 65% to 69.78%.

- -

- There was a greater N/S average of 17.08% toward favourable alternatives by P/S (30.22%) over E/S (13.14%). The overall F/S in Pentecostal streams fell below 75%.

- -

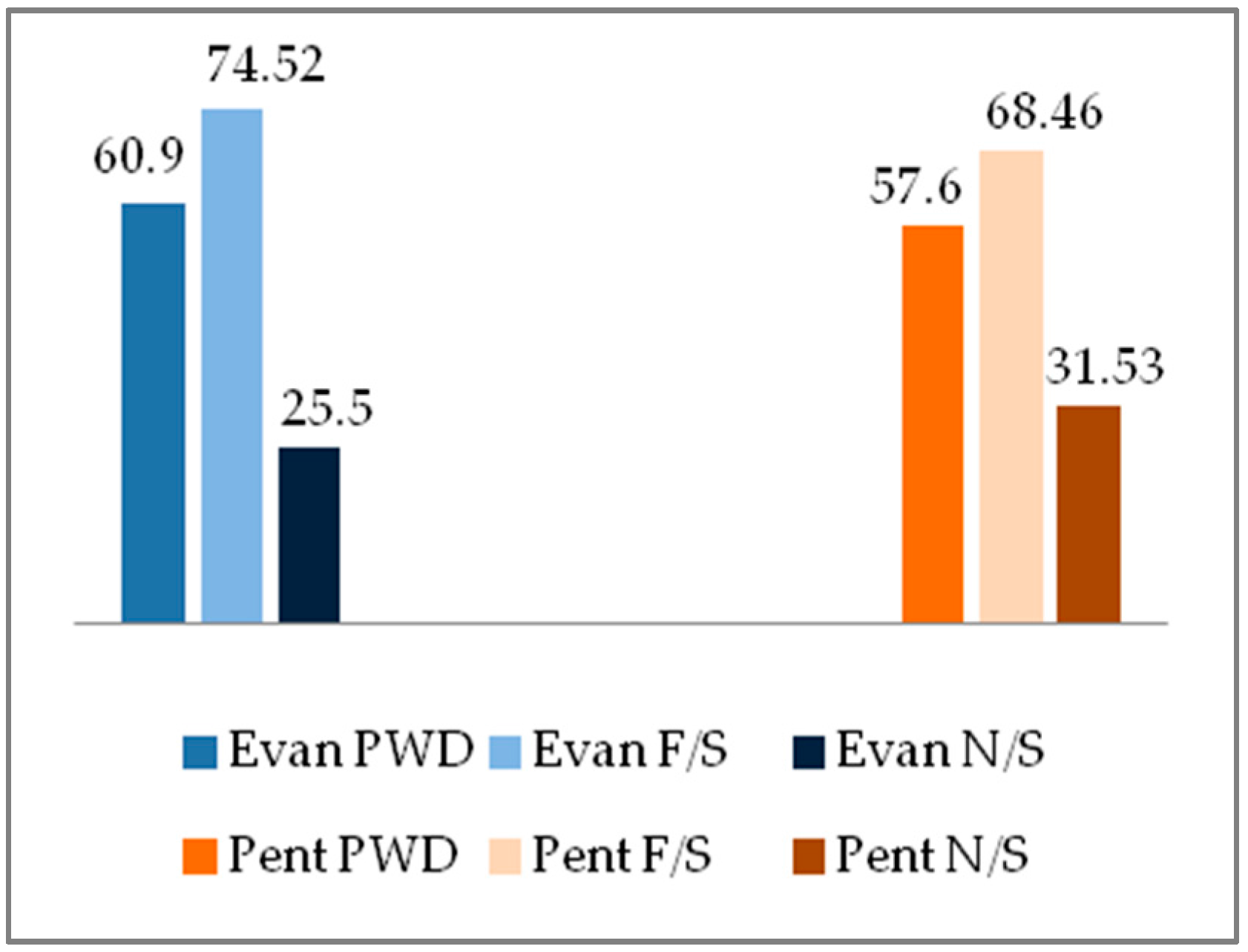

- E/S had an overall average 13.62% increase from PWD of 60.90% to 74.52%.

- -

- P/S saw an overall average increase of 10.86% from PWD of 57.60% to 68.46%.

- -

- There was a greater N/S average of 6.03% who failed to adjust their view toward a favourable alternative by P/S (31.53%) over E/S (25.5%). The overall average percentage F/S in both streams fell below 75%.

- -

- E/S had an overall average increase of 5.09% from PWD of 78.54% to 83.63%.

- -

- P/S saw an overall average increase of 1.97% from PWD of 84.34% to 86.31%.

- -

- There was a greater N/S average of 2.60% toward a favourable alternative by E/S (16.30%) over P/S (13.70%). The overall average percentage shifts for both streams was over 75%.

5. Discussion

- -

- Christians who die by suicide go to hell (nil shift of 3.64% E/S and 4.35% P/S);

- -

- Christians who die by suicide have committed an unforgivable sin (nil shift of 1.82% E/S and 8.70% P/S);

- -

- Christians die by suicide due to lack of faith (nil shift of 9.10% E/S and 9.7% P/S);

- -

- Christians who die by suicide do not have opportunity to repent before they die (nil shift of 10.9% E/S and 10.87% P/S); and

- -

- Christians who die by suicide are influenced by the demonic (nil shift of nil shift of 56% E/S and 34.9% P/S).

Conflicts of Interest

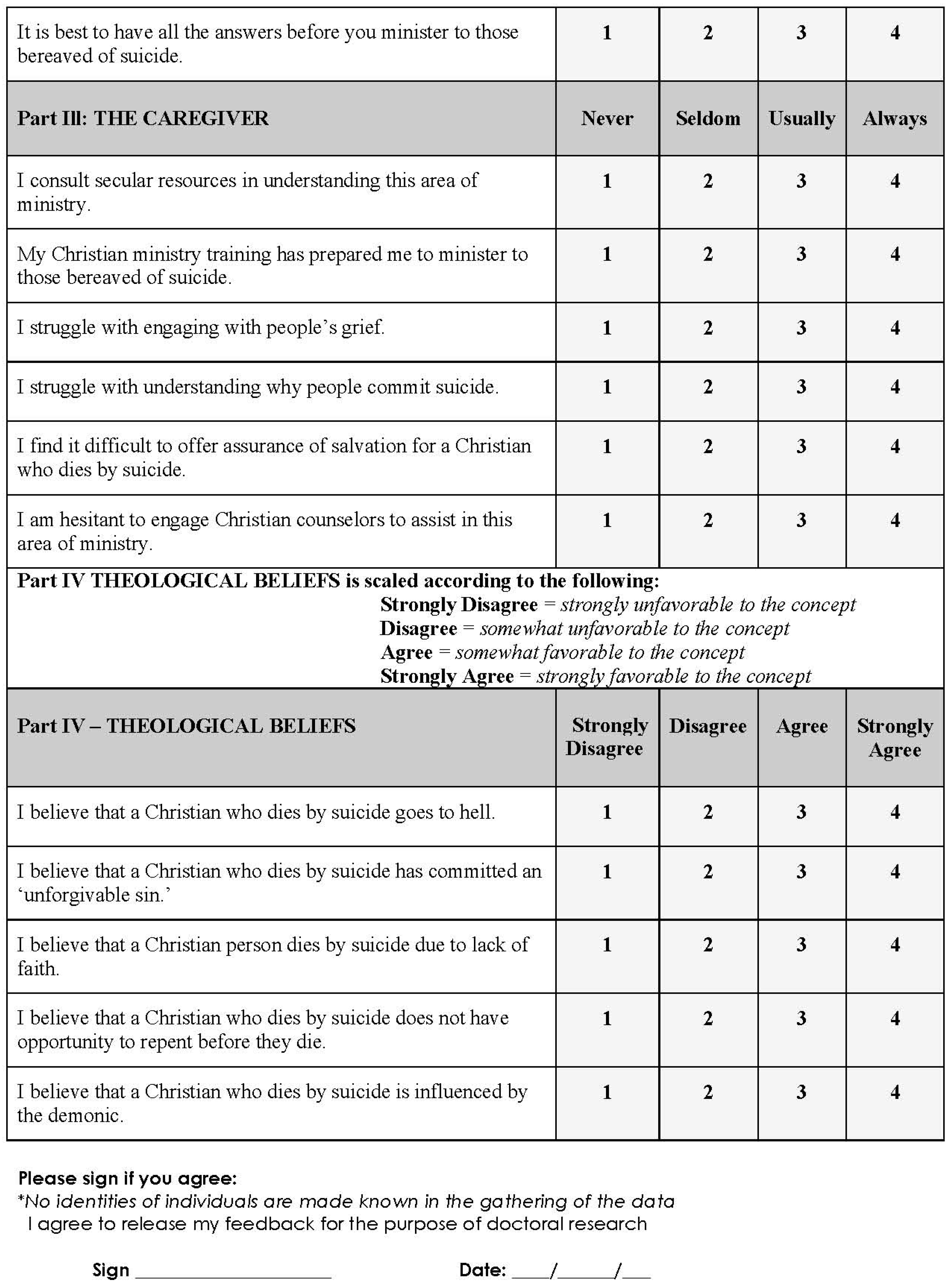

Appendix A

References

- Alvarez, Alfred. 1972. The Savage God: A Guide of Suicide. Wiltshire: Redwood Press Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, Herbert. 2010. Common Grief, Complex Grieving. Pastoral Psychology 59: 127–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronson, Elliot, Wilson Timothy, and M. Akert Robin. 1995–2010. The Need to Justify Our Actions—The Costs and Benefits of Dissonance Reduction. In Social Psychology, 6th ed. Available online: https://www.pearsonhighered.com/assets/samplechapter/0/2/0/5/0205796621.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2014).

- Babbie, Earl. 1998. The Practice of Social Research, 8th ed. Belmont: Wadsworth Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Beaton, Susan, Forster Peter, and Maple Myfanwy. 2013. Suicide and language: Why we shouldn’t use the ‘C’ word. InPsych 35: 30–33. Available online: https://www.psychology.org.au/publications/inpsych/2013/february/beaton/ (assessed on 15 March 2014).

- Bryman, Alan. 2012. Social Research Methods, 4th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Burns, Robert. B. 2000. Introduction to Research Methods, 4th ed. London: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Calvin, John. 1999. Commentary on Timothy, Titus, Philemon; Grand Rapids: Christian Classics Ethereal Library. Available online: http://www.ccel.org (accessed on 16 March 2015).

- Capps, Donald. 2001. Agents of Hope: A Pastoral Psychology. Eugene: Wipf & Stock Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Clinebell, Howard. 1984. Basic Types of Pastoral Care & Counselling: Resources for the Ministry of Healing and Growth. Nashville: Abingdon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Colt, George Howe. 1987. The history of the suicide survivor: The mark of Cain. In Suicide and Its Aftermath Understanding and Counselling the Survivors. Edited by E. J. Dunne and K. Dunne-Maxim. New York: Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, Joel. 2013. Cognitive Dissonance—Fifty Years of a Classic Theory. London: Sage Publications Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Crimes Act. 1958. Available online: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/legis/vic/consol_act/ca195882/s6a.html (accessed on 13 November 2015).

- Currier, Joseph, N. J. Jordan, Lichtenthal Wendy, A. Neimeyer Robert, and Roberts Kailey. 2013. Cause of Death and the Quest for Meaning after the Loss of a Child. Death Studies 37: 311–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, Stephen T., ed. 1989. Death and Afterlife. London: The Macmillan Press Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- De Vaus, David. 2002. Surveys in Social Research, 5th ed. Crows Nest: Allen & Unwin. [Google Scholar]

- Doka, Kenneth J. 2008. Disenfranchised Grief in Historical and Cultural Perspective. In Handbook of Bereavement Research and Practice. Advances in Theory and Intervention. Edited by M. Stroebe, R. Hansson, H. Schut and W. Stroebe. Washington: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Droge, Arthur, and Tabor James D. 1992. A Nobel Death: Suicide and Martyrdom among Christians and Jews in Antiquity. San Francisco: HarperCollins. [Google Scholar]

- Dunne-Maxim, K. 1987. Survivors and the Media: Pitfalls and Potential. In Suicide and Its Aftermath Understanding and Counselling the Survivors. Edited by E. J. Dunne and K. Dunne-Maxim. New York: Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Durkheim, Émile. 1951/1979. Suicide a Study in Sociology. Translated by J. Spaulding. New York: The Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Durling, Robert. 1996. The Divine Comedy of Dante Alighieri. Volume 1. Inferno. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dyregrov, Kari, Nordanger Dag, and Dyregrov Atle. 2003. Predictors of Psychosocial Distress after Suicide, SIDS and Accidents. Death Studies 27: 143–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fedden, Romilly. 1938. Suicide: A Social and Historical Study. London: Peter Davies Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Feigelman, William, Bernard S. Gorman, and John R. Jordan. 2009. Stigmatization and Suicide Bereavement. Death Studies 33: 591–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FNQ. 2012. Suicide Statistics in Australia. Available online: http://www.suicidepreventionfnq.org.au/statistics.html (accessed on 4 January 2015).

- Freeman, Stephen J. 2005. Grief and Loss: Understanding the Journey. Belmont: Thomson Books/Cole. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, Edwin H. 1985. Generation to Generation: Family Process in Church and Synagogue. New York: The Guildford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gerth, Hans Heinrich, and Charles Wright Mills. 1946. From Max Weber: Essays in Sociology. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, William, Albarracin Dolores, Eagly Alice, Brechan Inge, Lindberg Matthew J., and Merrill Lisa. 2009. Feeling validated versus being correct: A meta-analysis of selective exposure to information. Psychological Bulletin 135: 555–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hauser, M. J. 1987. Special Aspects of Grief after a Suicide. In Suicide and Its Aftermath Understanding and Counselling the Survivors. Edited by E. J. Dunne and K. Dunne-Maxim. New York: Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Hoy, William. 2013. Do Funerals Matter? The Purposes and Practices of Death Rituals in Global Perspective. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Isaac, Stephen, and Michael William. 1997. Handbook in Research and Evaluation: A Collection of Principles, Methods, and Strategies Useful in the Planning, Design, and Evaluation of Studies in Education and the Behavioural Sciences, 3rd ed. San Diego: Edits. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan, John R., and John L. McIntosh. 2011. Is Suicide Bereavement Different? A Framework for Rethinking the Question. In Grief after Suicide: Understanding the Consequences and Caring for the Survivors. Edited by John R. Jordan and John L. McIntosh. New York: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group. [Google Scholar]

- Kaslow, Nadine J., Tara C. Samples, Miesha Rhodes, and Stephanie Gantt. 2011. A Family-Oriented and Culturally Sensitive Postvention Approach with Suicide Survivors. In Grief after Suicide: Understanding the Consequences and Caring for the Survivors. Edited by John R. Jordan and John L. McIntosh. New York: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group. [Google Scholar]

- King, M. A. 2011. Truth-telling at funerals—Naming the shadows. Christian Century, February 8. [Google Scholar]

- Labovitz, Sanford, and Hagedorn Robert. 1971. Introduction to Social Research. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company. [Google Scholar]

- Leedy, Paul D., and E. Ormrod Jeanne. 2005. Practical Research: Planning & Design, 8th ed. Hoboken: Pearson Education Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Likert, Rensis, ed. 1932. A Technique for the Measurement of Attitudes. New York: New York University, vol. 140. [Google Scholar]

- Luther, Martin. 1483–1546. Table Talk. Edited by William Hazlitt. Available online: http://www.ccel.org/ccel/luther/tabletalk.txt (accessed on 25 March 2013).

- MacDonald, Michael, and Murphy Terence. 1990. Sleepless Souls, Suicide in Early Modern England. Oxford: Clarendons Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mangione, Thomas W. 1995. Mail Surveys: Improving the Quality. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Matthew, T. K. 2000. Ministry Research Simplified: A Guide for Doctoral Candidates Pursuing Quantitative Research. Oklahoma: Matthew, T. K. [Google Scholar]

- McLean, Loyola, and Marie-Thérèse Proctor. 2012. The Pilgrim Road to Flourishing: When the Psychotherapeutic and the Spiritual Journey’s Meet. In Beyond Well-Being: Spirituality and Human Flourishing. Edited by Maureen Miner, Martin Dowson and Stuart Devenish. Charlotte: Information Age Publishing, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Minois, Georges. 1995. History of Suicide, Voluntary Death in Western Culture. Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, William R. 2002. Research in Ministry: A Primer for the Doctor of Ministry Program. Chicago: Exploration Press. [Google Scholar]

- Neale, Robert E. 1973. The Art of Dying. San Francisco: Harper & Row Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Parachin, Victor M. 2015. Why Suicide Death Is Different How to Help Grievers. The Priest. Available online: https://www.osv.com/OSVNewsweekly/Faith/Article/TabId/720/ArtMID/13628/ArticleID/18452/Why-Suicide-Death-Is-Different.aspx (accessed on 25 June 2017).

- Parkes, Colin Murray. 2008. Bereavement Following Disasters. In Handbook of Bereavement Research and Practice. Advances in Theory and Intervention. Edited by M. Stroebe, R. Hansson, H. Schut and W. Stroebe. Washington: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Parsons, R. D. 1993. Suicide Survivors: Intervention—Prevention—Postvention. In Clinical Handbook of Pastoral Counselling Volume 2. Edited by R. J. Wicks and R. D. Parsons. Mahwah: Integration Books. [Google Scholar]

- Raphael, Beverley. 1985. The Anatomy of Bereavement: A Handbook for Caring Practitioners. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Rubey, C. T., and D. C. Clark. 1987. Suicide Survivors and the Clergy. In Suicide and Its Aftermath Understanding and Counselling the Survivors. Edited by E. J. Dunne and K. Dunne-Maxim. New York: Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin, Simon. 2014. Loss and mourning in the Jewish tradition. Omega 70: 79–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanders, Catherine M. 1989. Grief: The Morning After, Dealing with Adult Bereavement. New York: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Schaff, Philip, ed. 1997. Nicene and Post-Nicene-1, Fathers of the Christian Church. Volume II. St. Augustine’s: City of God and Christian Doctrine. Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Selby, Susan. 2013. New Every Morning: Integrating Current Development in Grief Theory and Practice with Jesus’ Compassion and Teaching. In Loss and Discovery. Edited by M. Wesley. Melbourne: Mosaic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shneidman, Edwin. 1983a. Orientations towards Death. In The Psychology of Suicide. Edited by E. S. Shneidman, N. L. Farberow and R. E. Litman. New York: Jason Aronson, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Shneidman, Edwin. 1983b. Suicide as a Taboo Topic. In The Psychology of Suicide. Edited by E. S. Shneidman, N. L. Farberow and R. E. Litman. New York: Jason Aronson, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Stengel, Erwin. 1964. Suicide and Attempted Suicide. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. [Google Scholar]

- Stroebe, Margaret S., and Schut Henk. 2010. Meaning Making in the Dual Process Model of Coping with Bereavement. In Meaning Reconstruction & Experience of Loss. Edited by R. Neimeyer. Washington: American Psychology Association. [Google Scholar]

- Tarnas, Richard. 1991. The Passion Of The Western Mind: Understanding The Ideas That Have Shaped Our World View. New York: The Random House Publishing Group. [Google Scholar]

- Vandecreek, Larry, and Kenneth Mottram. 2009. The Religious Life during Suicide Bereavement: A Description. Death Studies 33: 741–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsh, F. 2004. Spirituality, Death, and Loss. In Living Beyond Loss: Death in the Family Second Edition. Edited by F. Walsh and M. McGoldrick. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. [Google Scholar]

- Werth, James L. 1996. Rational Suicide?: Implications for Mental Health Professionals. Washington, USA: Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Wertheimer, Alison. 2001. A Special Scar: The Experiences of People Bereaved by Suicide, 2nd ed. Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Worden, William J. 2009. Grief Counselling and Grief Therapy: A Handbook for the Mental Health Practitioner, Fourth Edition. New York: Singer Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Zachman, Randall C. 2008. John Calvin and Roman Catholicism: Critique and Engagement, Then and Now. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | Portions of this paper are reproduced with permission from the Journal of Contemporary Ministry published by Harvest Bible College, 2016. |

| 2 | At the time of my experience and the writing of my doctoral thesis, I did not have any real appreciation of the magnitude of the numbers of women affected by this mental disorder until coming across the Netflix documentary produced by Brooke Shields, When the Bough Breaks. |

| 3 | Once the research was complete, this handbook was revised and renamed, The Pastor’s Handbook A Complete Theological & Practical Response to Suicide—Entering the World of the Suicide & the Bereaved (2015). Lulu, Raleigh, NC. This resource still undergirds ongoing workshops. A condensed version, Suicide Prevention, Intervention & Postvention Care Training Manual (2016). Lulu, Raleigh, NC, is also used for training both Christian and non-Christian audiences. |

| 4 | See Appendix A: Pre-Workshop Survey—Doctoral Research. |

| 5 | Survey statement - I find it difficult to offer assurance of salvation for a Christian who dies by suicide. |

| Regions | Att. No’s | P/S (CS) | E/S (CS) | Combined Ministries Represented Completing Surveys |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Victoria | 83 | 19 | 36 | Snr. Pastors (3) Pastoral Carers (9) Prayer/Healing (17) Counsellors (6) Connect Groups (1) Chaplains (3) Church Attendees (12) Youth Leaders (2) Families Ministries (1) Elders (1) |

| Newcastle | 8 | 4 | 3 | Snr. Pastors (2) Pastoral Carers (4) Counsellors (1) |

| Queensland | 30 | 20 | 7 | Pastoral Carers (8) Prayer/Healing (4) Chaplains (3) Counsellors (4) Women’s Ministries (2) Snr. Pastors (3) Church Attendees (3) |

| Tasmania | 5 | 2 | 3 | Snr. Pastors (1) Elders (2) Youth Workers (1) Chaplains (1) |

| Auckland NZ | 3 | 1 | 2 | Mission Carers (2) Youth Leaders (1) |

| Wellington NZ | 4 | 4 | Youth Leaders (1) Chaplains (1) Church Leadership (2) | |

| TOTAL | 133 | 46 | 55 |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Staley, A. Identifying Ingrained Historical Cognitive Biases Influencing Contemporary Pastoral Responses Depriving Suicide-Bereaved People of Essential Protective Factors. Religions 2017, 8, 267. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel8120267

Staley A. Identifying Ingrained Historical Cognitive Biases Influencing Contemporary Pastoral Responses Depriving Suicide-Bereaved People of Essential Protective Factors. Religions. 2017; 8(12):267. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel8120267

Chicago/Turabian StyleStaley, Astrid. 2017. "Identifying Ingrained Historical Cognitive Biases Influencing Contemporary Pastoral Responses Depriving Suicide-Bereaved People of Essential Protective Factors" Religions 8, no. 12: 267. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel8120267