1. Introduction

In courses that cover the Reformation, it is always important to tie Martin Luther’s reforms to the historical context in which they occurred. For example, the 95 theses need to be understood in the context of late medieval Church practices of penance and indulgences. Modern students may not have first-hand experience of indulgences, but most do know the Lord’s Prayer. Luther used the Lord’s Prayer both in his own prayers, and as a vehicle for communicating his most fundamental theological concepts, such as justification by faith alone, the alien and proper work of God, the corruption of the will and the hiddenness of God. While each of these concepts involves complex theological doctrines, Luther’s writings on the Lord’s Prayer can make these concepts easily accessible to students and show the historical context in which they developed. Particularly helpful for teaching these concepts is the Large Catechism of 1529, for which Lucas Cranach provided illustrations of Luther’s teachings, something not commonly found in Luther’s writings. These illustrations were intended to reinforce Luther’s points, but they also reflect the ways in which his interpretations of the Prayer changed as the historical context changed.

In this study, I will examine how Luther presents some of his fundamental theological concepts to laypeople in his teachings on the Lord’s Prayer and how, in the case of the

Large Catechism, Lucas Cranach illustrated these concepts. It is important for students to understand that Luther’s reforms were not static, but developed over time and were influenced by historical events. Luther’s writings on the Prayer are easily accessible and show both his main teachings and the historical context in which they occurred

1.

2. Luther’s Works on and Use of the Lord’s Prayer

Over the course of his career, Luther preached and wrote upon the Lord’s Prayer twenty-one times

2 (

Carmignac 1969, pp. 166–70). His seven most extensive studies of the Prayer were all intended for the laity.

An Exposition of the Lord’s Prayer for Simple Laymen (

Luther 1969, 42.19–81;

Luther 1883, 2.80–130), based on a series of sermons he gave in 1517, was published in 1519. The

Personal Prayer Book of 1522 (

Luther 1969, 43.11–45;

Luther 1883, 10(II).375–406) was intended as a replacement for the popular medieval prayer books, and the format follows the traditional Roman Catholic prayer book structure but with new interpretations. His

Ten Sermons on the Catechism (

Luther 1969, 51.169–82;

Luther 1883, 30(I).94–109) were delivered in 1528, and the

Large and

Small Catechisms (

Luther 1959) appeared in 1529. These three works cover the traditional sections of Christian catechisms, that is, the Ten Commandments, the Apostles’ Creed, the Lord’s Prayer and the sacraments. His

Commentary on the Sermon on the Mount is a series of sermons he gave in the early 1530s and, lastly,

A Simple Way to Pray (

Luther 1969, 43.193–211;

Luther 1883, 38.58–75), written in 1535, is a published letter to his barber and gives instruction on daily prayer.

These writings on the Lord’s Prayer were central to Luther’s efforts to change the practices of his congregation regarding prayer, including their use of medieval prayer books. These prayer books, such as Books of Hours or Breviaries, emphasized reciting prescribed prayers and following the canonical hours. Luther describes his own prayer methods in his writings, namely, how first thing in the morning and again in the evening, preferably kneeling or standing before an open window, he would recite the Ten Commandments, then the Apostles’ Creed and some Scripture, followed by the Lord’s Prayer, saying each phrase of the Prayer and elaborating upon it before going on to the next phrase

23. After the Lord’s Prayer, he prayed the same way through the Ten Commandments and the Apostles’ Creed as time permitted or, as he says, unless he fell asleep. In his two

Catechisms, Luther’s order of Commandments, Creed and then Lord’s Prayer actually rearranges the traditional form of catechisms, which used the order of Creed, Lord’s Prayer and then Commandments. The traditional order corresponded to the virtues of faith, hope and love, whereas Luther revised the order because he instead understood the Commandments, Creed and Prayer to represent a medical diagnosis of the human condition, respectively the description of the sickness, the announcement of the cure and the medicine needed (

Wengert 2009).

Luther’s purpose in using the Commandments, the Creed and the Lord’s Prayer also differed significantly from medieval prayer books in that his goal was to teach laypeople to develop their own prayers, rather than to repeat the Lord’s Prayer or other prayers a prescribed number of times a day using repetitive methods such as the rosary. These changes to the medieval method of prayer led to rumors that Luther rejected prayer of any kind, for in the

Large Catechism of 1529 he says opponents were “alleging that since we reject false and hypocritical prayers we teach there is no duty or need to pray (

Luther 1959, p. 421)”

4. He denied this, saying that he rejected only the abuse of prayer. For Luther, prayer is abused when it is not based on what is found in Scripture. This error results from the fact that, though we know there is a God, God is hidden and we need him to reveal by his Word how and what to pray. For Luther, God has revealed in the Lord’s Prayer what we are to pray and therefore we know he will hear it. Luther ties prayer to the second commandment, “Thou shalt not take the name of the Lord thy God in vain,” which he interprets as a command to call upon God. Likewise, the command “Ask, and it will be given you” (Mt 6:7) shows for Luther that God has promised to hear and answer prayer. It is the revealed nature of the Lord’s Prayer and the promises attached to it that make it unique among prayers.

Luther’s method of praying by expanding upon the different petitions of the Lord’s Prayer one at a time was the same method he used in explicating the Prayer

5. In the remainder of this essay, I will examine Luther’s interpretations of six of the seven petitions and consider the Cranach woodcuts from the

Large Catechism that were used to illustrate Luther’s theological concepts. Since, over the 20 years he writes on the prayer, Luther continually found new ways to explain his theological principles, I will also discuss how his interpretations changed over time and were influenced by historical events.

3. The First Petition of the Prayer—Preaching True Faith

In his 1519

Exposition on the Lord’s Prayer, Luther’s focus in the first petition, “Hallowed be Thy name,” (

Figure 1) is on what this petition says about us. As he says, “when we pray that God’s name be hallowed in us, this implies that it is not yet holy in us; if it were, we should not have to pray for it” (

Luther 1969, 42.33). He thinks that when we pray this petition we confess that we have robbed God of what rightly belongs to him, namely, that his name be holy in us and we should be terrified of the judgment that we deserve. However, God has told us to pray this way because he intends to be merciful and, in confessing that God’s judgment about us is true, we justify God and so are justified by God.

In the 1520s, as Catholic opposition and discord among reformers grew, Luther came to interpret this petition differently, with a greater concern for the threat posed by false teachings that were leading people astray. Thus, in the 1522

Prayer Book, he sees the petition as asking for help to honor God, to serve others, to pray for proper things and not to be deceived by false doctrine. He states in the

Prayer Book that in this petition we ask God to “help us root out all false belief and superstition. Help us bring to naught all heresies and false doctrines which are spread under the guise of your name” (

Luther 1969, 43.30–31). God’s help comes through his Word, so this petition is asking God for his Word through preaching, which reflects how Luther saw preaching just as important as the traditional focus on the Eucharist.

Figure 1.

First petition.

Figure 1.

First petition.

In the

Large Catechism of 1529, both Luther’s explication of the first petition and Lucas Cranach’s woodcut (

Figure 1) reflect this concern for preaching. The image is of a pastor preaching to his congregation, associating this petition with the need for true preaching to counter false doctrine

6. This image reinforces Luther’s increasing emphasis on both the need for pastors to preach properly and for the congregation to listen to the Word of God. As Luther writes in the

Large Catechism, “we ought constantly to cry out against all who preach and believe falsely and against those who attack and persecute our Gospel and pure doctrine and try to suppress it, as the bishops, tyrants, fanatics and others do” (

Luther 1959, p. 426). For students, then, Cranach’s woodcut can be understood as part of a larger shift in Luther’s teaching toward an increased emphasis on the need to combat through preaching the false doctrines that threatened Christians.

After Protestants failed to achieve either unity at the Marburg Colloquy in 1529 or reconciliation with the Catholics at the Diet of Augsburg in 1530, Luther’s concern over false teaching became more strident. In his 1530

Commentary on the Sermon on the Mount, he says that the first petition opposes “every kind of false belief and worship, all of hell, and all sin and blasphemy” (

Luther 1969, 21.146). In

A Simple Way to Pray of 1535 he says the petition asks God to “destroy and root out the abominations, idolatry and heresy of the Turk, the Pope and all false teachers and fanatics” (

Luther 1969, 43.195).

4. The Second Petition—Kingdoms

As with the first petition, Luther’s interpretation of the second petition of the Lord’s Prayer, “Thy kingdom come,” (

Figure 2) shows a change in emphasis over time, namely, in his thought concerning different types of kingdoms. In the 1519

Exposition, he contrasts God’s kingdom with the kingdom of the devil. He says the kingdom of the devil is in this world, while the kingdom of God is in the godly person. He writes, “all of us dwell in the devil’s kingdom until the coming of the kingdom of God.” (

Luther 1969, 42.38). He says that in praying for God’s kingdom to come, we confess that it has not yet come to us and that we are still outside of his kingdom. Although deserving judgment for this, when we justify God’s judgment by confessing his Word as true, God heals and pardons us. Also, because God’s kingdom is hidden from us, we do not enter it, rather here we pray that it will come to us. He writes, “if you want to know the kingdom of God, do not go far afield in search of it…it is not only close to you, it is in you.” (

Luther 1969, 42.41).

In his work on the two

Catechisms of 1529, he alters his interpretation of the second petition, emphasizing that God’s kingdom comes whether we pray for it or not. As he says in the

Small Catechism, “To be sure, the kingdom of God comes of itself, without our prayer; but we pray in this petition that it may also come to us.” (

Luther 1959, p. 346). We cannot hasten or delay God’s kingdom; rather, we pray that it may come to us so we can enjoy something that is already underway. For Luther, God’s kingdom comes to us through the faith that is brought by the Holy Spirit.

Figure 2.

Second petition.

Figure 2.

Second petition.

This principle that God’s kingdom comes to us by the Holy Spirit is illustrated by Cranach’s

Large Catechism woodcut (

Figure 2). The woodcut is accompanied by a reference to Acts 2, showing the moment when the Holy Spirit comes upon the disciples. Each disciple is shown with a tongue of fire, and the Holy Spirit, as a dove, is above them. In the

Large Catechism, Luther writes, “So we pray that [God’s] kingdom may prevail among us through the Word and the power of the Holy Spirit, that the devil’s kingdom may be overthrown and he may have no right or power over us” (

Luther 1959, p. 427).

In the same year as the

Catechisms, the second Diet of Speyer of 1529 rescinded the ability of political leaders to decide the religion of their territories, an ability that had proven to be very favorable to Protestant leaders. This was followed by the failure of Protestant and Catholic unity at the Diet of Augsburg of 1530 and the formation of the Protestant Schmalkaldic League of 1531 to oppose the Holy Roman Emperor and Catholic princes in the Empire militarily. Amid these political developments and increasing tensions, by the 1530s the focus of Luther’s interpretation of the second petition changed from the coming of God’s kingdom to protecting believers from kingdoms opposed to God. In the 1530

Commentary on the Sermon on the Mount, for instance, he says that in the second petition we ask that God would “shatter all the kingdoms that rage against His kingdom, so that it alone may remain” (

Luther 1969, 21.146). Moreover, according to the 1535

A Simple Way to Pray, these raging kingdoms are in this world and are people in authority, both clerical and political, who take their power, wealth and position and use them for evil. He says, “they are many and mighty; they plague and hinder the tiny flock of God’s kingdom who are weak, despised and few.” (

Luther 1969, 43.195). In this 1535 work, Luther stresses that only by God’s constant protection do the faithful of God’s kingdom survive the attacks of the kingdoms of this world. Luther’s writing on the Prayer after the time of the

Catechisms, then, shows that the changing political context influenced his explication of the second petition to focus less on the spiritual battle between God’s kingdom and the kingdom of the devil, and more on the dangers posed by political authorities and their earthly kingdoms.

5. The Third Petition—The Alien and Proper Work of God

Luther’s interpretations of the third petition, “Thy will be done on earth as in heaven”, (

Figure 3) generally concern the corruption of human will and one of his favorite theological principles, the alien and proper work of God. For Luther, God’s alien work is to break the sinful nature of believers by convicting them of sin before the Law and making them aware of the punishment sin deserves. Central to this alien work is the crucifixion of Jesus. The proper work of God is to justify believers by faith alone and to enable believers to will what God wills. Central to this proper work is the resurrection of Jesus.

In his 1519

Exposition he distinguishes between what he terms the “old Adam” and the justified believer and he rejects the idea that we have some ability to do good by our own will. For Luther, because a believer is both fully just and unjust, the “old Adam” is a desire for evil, which corrupts the will and renders the individual unable, apart from by grace, to obey God’s revealed will, which is the Law. As a result, God must break down and rebuild the will; he must destroy in order to renew. Luther writes, we “must despair utterly of ever having or attaining a good will…A good will is found only where there is no will. Where there is no will, God’s will, which is the very best, will be present.” (

Luther 1969, 42.48). For Luther in 1519, the third petition shows we do not have a free will that can choose the good and so be rewarded by God for its virtue. Instead, our will must be overcome by God, which is a process begun when we accept God’s judgment of us as true and so here we are praying that God do his alien work of breaking our will and his proper work of rebuilding it, so by grace it can choose the good and love God.

Figure 3.

Third petition.

Figure 3.

Third petition.

In the

Large Catechism, Cranach’s woodcut (

Figure 3) for this petition references Matthew 27 and is an image of Jesus carrying the cross, surrounded by persecutors. This image reflects two things. First, Jesus’ crucifixion is central to Luther’s idea of the alien and proper work of God, in that believers cannot do God’s will unless they have first been broken before the Law and its punishments. Second, the image shows how, by the time of the

Catechisms of 1529, Luther’s understanding of the third petition of the Prayer has become increasingly concerned with the attacks of the devil and persecutors. As he says in the

Large Catechism, the devil and the world will bring suffering to believers, “For where God’s Word is preached, accepted, or believed and bears fruit, there the blessed holy cross will not be far away” (

Luther 1959, p. 429).

This shift toward an emphasis on persecution is maintained in later explications of the third petition. In

A Simple Way to Pray of 1535, for instance, Luther says this third petition shows that no Christian may have peace in this life since God is constantly stripping the will of evil and defending the Gospel from the devil, his minions and ourselves. He says that though the world fights against God’s kingdom and children, nevertheless in this petition we take confidence that God’s will shall prevail both in the world and in ourselves. He writes that the world tries “with every evil intention to destroy [God’s] name, word, kingdom and children. Therefore, dear Lord, God and Father, convert them and defend us” (

Luther 1969, 43.196). As with the two previous petitions, his interpretation here shows a growing concern with opposition to his reforms from both Catholics and other Protestants. However, despite these shifting concerns, it is important for students to understand that for each of the first three petitions Luther’s primary purpose remains one of pastoral guidance, with the goal of teaching people fundamental theological principles such as the alien and proper work of God, the corruption of the will and the hiddenness of God, in an uncomplicated way.

6. The Fourth Petition—Bread

Developments regarding the fourth petition, “Give us this day our daily bread,” (

Figure 4) reveal the impact of Luther’s work on translating the Bible into German. According to the

Exposition of 1519, the “bread” of this petition is the Word of God. However, because God is hidden we cannot summon God’s Word and so unless God decides to reveal his Word to us, this bread remains hidden also. Nevertheless, God has bound himself by a promise to be present to the faithful in preaching and in the sacraments, and therefore part of the fourth petition is prayer for the clergy so that faithful preaching is available and the sacraments are properly administered. Prayer for the clergy is essential for access to God’s Word, and the lack of good clergy and the sacraments are punishments for not praying this petition sincerely. He writes, “the bread, the Word and the food are none other than Jesus Christ our Lord himself…Christ our bread is given in a twofold manner. In the first place, outwardly, by persons, for instance, by priests and teachers. And this is done in two different ways: first, through words; second, through the sacrament of the altar” (

Luther 1969, 42.56–7).

This connection between the bread of the fourth petition and the Eucharist follows two significant traditions. First, in Christian history the version of the Lord’s Prayer found in Matthew has traditionally taken precedence over the one found in Luke, and Luther adopts this same method. Second, in the Vulgate Bible Jerome translated the Greek word

epiousion of Matthew (6:11) with the Latin

supersubstantialem, a word meaning the bread ‘necessary for existence.’

Supersubstantialem was a word invented by Jerome and used nowhere else in the Vulgate. For the version in Luke (11:3), Jerome used

quotidianum or ‘daily’ bread. Luther in 1519 accepts the patristic tradition found in Jerome and other Fathers and which was common in both the Eastern Church and the medieval Catholic church, namely, understanding ‘the bread necessary for existence’ in the Lord’s Prayer in terms of the Eucharist (

Stevenson 2004, pp. 117–50)

7.

When Erasmus published his Greek New Testament with a new Latin translation in 1516, in both Matthew and Luke he used

quotidianum (

Erasmus 1986b, p. 11)

8. In his

Annotations which accompanied his New Testament, Erasmus defended Jerome’s use of

supersubstantialem as a valid rendering of the Greek but thought

quotidianum was better. When Luther translated the Bible into German in 1522 he used Erasmus’ edition of the New Testament, and in translating both Matthew and Luke used

täglich, ‘daily.’ This then influenced his studies of the Prayer. In 1519 he had understood the bread as the Word of God in the sacrament. By his 1528

Sermons on the Catechism, however, he entirely set aside this interpretation of bread in terms of the sacrament and adopted a more material understanding

9.

Figure 4.

Fourth petition.

Figure 4.

Fourth petition.

The

Large Catechism woodcut (

Figure 4) for the fourth petition refers to John 6 and shows Jesus feeding the multitude. In the image there is a boy with a few loaves and fishes beside Jesus. In the background there are casks of water, or perhaps beer, which is not in the Bible verse, but no doubt familiar to Luther’s readers. Noticeably, the picture is not about Jesus and the disciples at the Last Supper in the upper room, which would connect the bread in the petition to the sacrament. Rather it illustrates the more physical interpretation of bread to which Luther adheres from the 1520s on.

In both the

Large and

Small Catechisms of 1529 he says that in the fourth petition we are praying for our crops, peace and good government, and acknowledging that bad rulers, war, hunger, a poor economy and other such calamities are all in God’s hand. We are here praying for governmental authorities, justice and loyal subjects and against the devil and his followers who constantly try to disrupt society. This material interpretation of bread shows a clear break with the medieval and patristic tradition, as well as his own 1519

Exposition on the fourth petition, and dates to his translation of the Bible in 1522. No doubt this interpretation was reinforced by the crop failures of the mid 1520s and the Peasants War of 1525, and is one he retains throughout his later writings. For instance, in

A Simple Way to Pray of 1535, Luther notes that in this petition we pray that God “grant us thy blessing also in this temporal and physical life. Graciously grant us blessed peace. Protect us against war and disorder” (

Luther 1969, 43.196). He says this petition is a prayer for emperors, princes, townsmen and farmers, good harvests and our family.

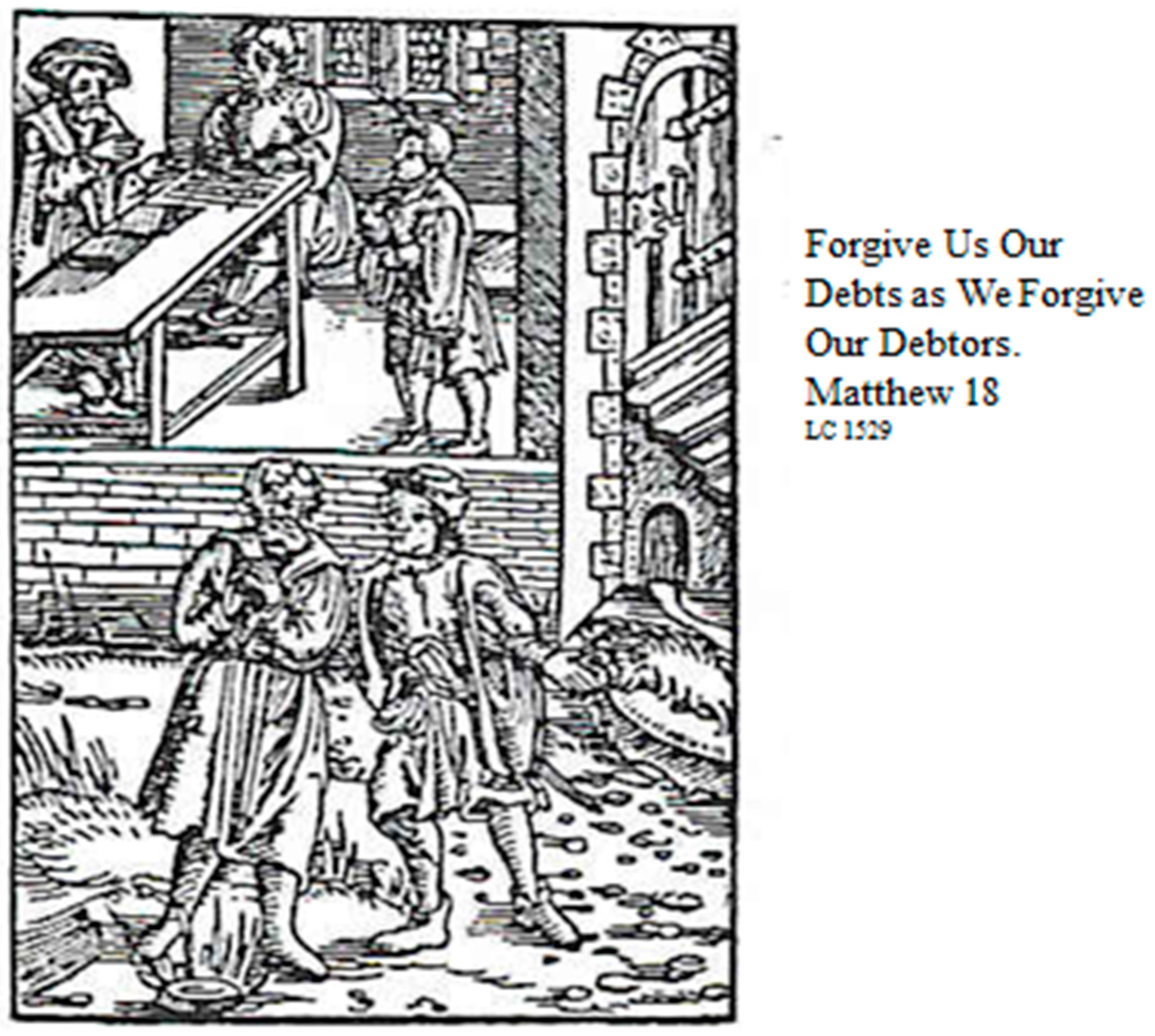

7. The Fifth Petition—The Problem of the If

Luther’s interpretations of the fifth petition, “forgive us our debts as we forgive our debtors,” (

Figure 5) reveal a struggle to solve a significant theological problem, namely, does God only forgive our sins when we first forgive our neighbor

10? In his 1519

Exposition, Luther states that praying this fifth petition is a sin of disobedience for those who refuse to forgive their neighbor, are spiritually offended by their neighbor’s lifestyle, or consider themselves better than others. He notes that a person’s sins will “not be imputed if they denounce their sins, ask for mercy and forgive their debtors” (

Luther 1969, 42.70). It is the “if” that caused Luther concern, since if God’s forgiveness is based upon our prior action of forgiving our neighbor, then this would appear to be contrary to the principle of justification by faith alone. An early solution to the problem is found in his 1528

Sermons on the Catechism, where he states that in asking God to forgive our sins, it is “not that He does not give it [forgiveness] without our prayer… But [this petition] is to be done in order that we may acknowledge it. He adds that God, “enjoins it upon you as a sign, that you may be assured that, if you forgive, you too will be forgiven” (

Luther 1969, 51.178–9).

Figure 5.

Fifth petition.

Figure 5.

Fifth petition.

As Luther develops his thought on this fifth petition, he finds the answer to the problem lies in the hiddenness of God, meaning that God cannot be known unless he reveals himself and even then he does so in such a way that he appears contrary to what is expected. Just as God is hidden, so too is his forgiveness. In Cranach’s woodcut for the

Large Catechism (

Figure 5), the verse reference is to Matthew 18, and the image tells the story of the unmerciful servant. At the top of the woodcut the servant is forgiven by his king of an immense debt and then, at the bottom of the image, that servant refuses to forgive another servant of a minuscule debt. In the parable, the servant is forgiven, but upon refusing to forgive another, is thrown by the king into prison and tortured.

The woodcut depicts the man who hopes for forgiveness while being unforgiving himself, but confronting him is God’s command to forgive and the punishment for not forgiving. For Luther, God’s Word contains both Law and Gospel. God’s forgiveness and mercy (Gospel) are here hidden under the command (Law) that one forgive one’s neighbor. We naturally focus on the command, not realizing that God’s forgiveness here is hidden. He writes, “Not that [God] does not forgive sin even without and before our prayer; and he gave us the Gospel, in which there is nothing but forgiveness, before we prayed or even thought of it. But the point here is for us to recognize and accept this forgiveness.” (

Luther 1959, p. 432). What the fifth petition reveals is that, “if you forgive, you have the comfort and assurance that you are forgiven in heaven.” (

Luther 1959, p. 433). Thus, for Luther, forgiving our neighbor is not a prerequisite for our own forgiveness, but a sign of the promise that we are forgiven, and in this promise there is assurance. God’s Word here enables believers to recognize the hidden forgiveness that is already present.

In

A Simple Way to Pray of 1535, Luther’s primary concern is with the first part of this petition, “Forgive us our debts.” He says this asks God, “Do not look upon how good or how wicked we have been but only upon the infinite compassion which thou hast bestowed upon us in Christ.” Luther is not as concerned with the second half of the petition, adding, “Anyone who feels unable to forgive, let him ask for grace so that he can forgive; but that belongs in a sermon.” (

Luther 1969, 43.197).

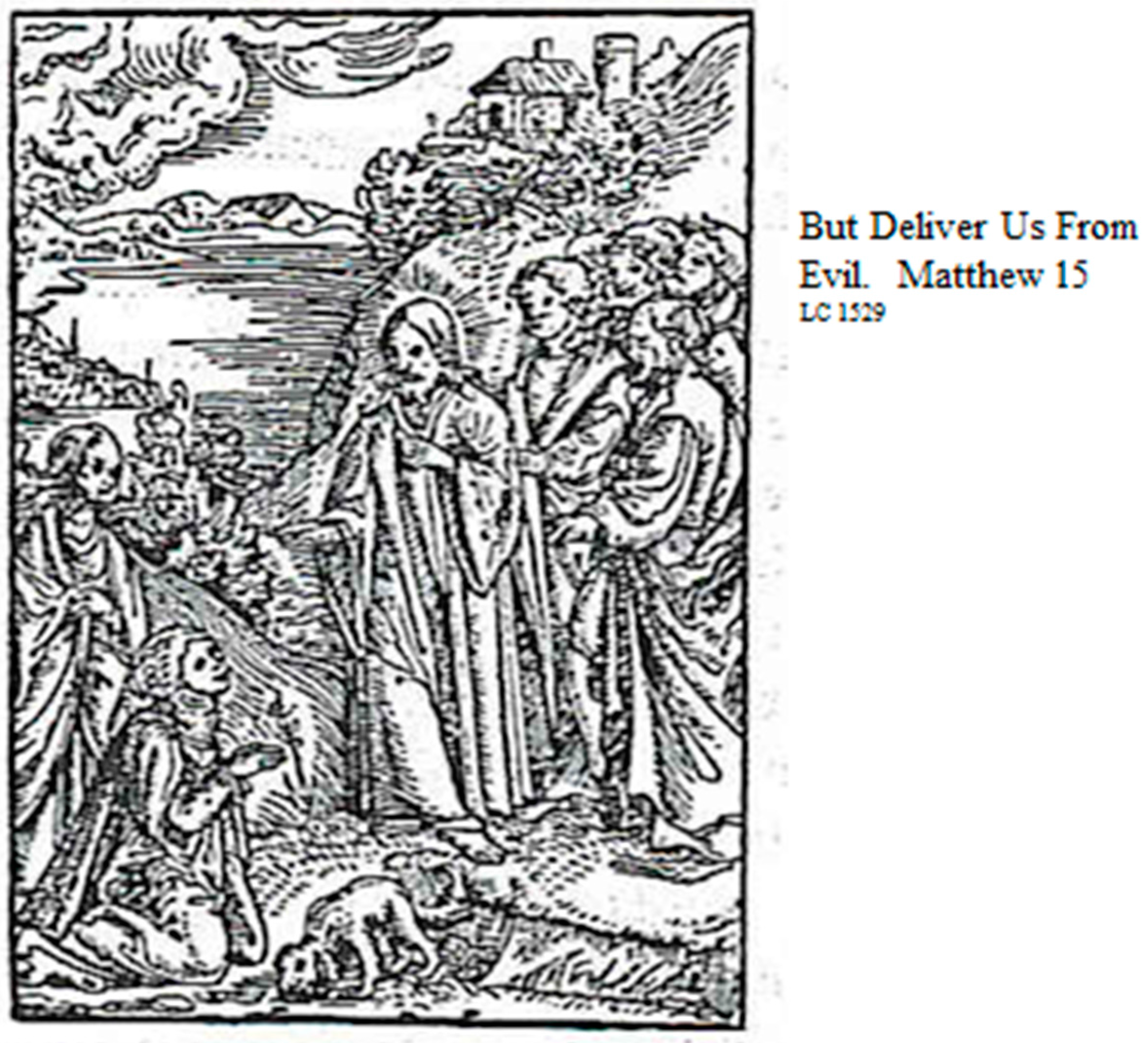

8. The Seventh Petition — Sickness and Death

It might be expected that in his exposition of the seventh petition, “deliver us from evil,” (

Figure 6) Luther’s interpretations would, over time, follow the same pattern as with previous petitions and focus increasingly on his theological opponents and the threats they posed to the faith. Surprisingly, however, he instead shows a growing concern with sickness and death. In his

Exposition of 1519, for example, he says that although we often take the seventh petition as a prayer for deliverance from pain and distress, we should instead pray for what is emphasized in the first three petitions, namely, God’s honor. He writes, “we should pray for deliverance from evil so that trials and sin may cease and that God’s will may be done and his kingdom come, all to the glory and honor of his holy name” (

Luther 1969, 42.76).

Figure 6.

Seventh petition.

Figure 6.

Seventh petition.

In the

Large Catechism, Luther moves away from emphasizing God’s honor in the seventh petition and introduces instead ideas about human sickness and affliction. Luther says that since all evil comes from the devil, we pray in this petition to be protected and delivered from him, since he seeks our life, afflicts our bodies and brings “all the tragic misery and heartache of which there is so incalculably much on the earth.” (

Luther 1959, p. 435). Once again, Cranach’s woodcut (

Figure 6) complements this new emphasis, referencing Matthew 15. In the biblical passage and the image, a Canaanite woman begs Jesus to heal her daughter, but Jesus at first refuses to do so, saying that he does not throw the children’s food to dogs. She responds that even dogs get the crumbs on the floor, whereupon Jesus praises her faith and heals her daughter. Cranach places a dog in the foreground by the kneeling woman, illustrating Jesus’ initial answer and her response. For Luther, just as the woman accepts Jesus’ likening her to a dog and uses his own words in her request, so too in the Lord’s Prayer we use Jesus’ own words to find the medicine for the sickness and misery in the world.

In

A Simple Way to Pray of 1535, Luther shifts the emphasis away from sickness and towards a new theme, death, and says that though we long for death we ask that God aid us amidst such great evil and grant us a firm faith when we die. He writes that in this petition we pray for God to “help us to pass in safety through so much wickedness and villainy; and, when our last hour comes, in thy mercy grant us a blessed departure from this vale of sorrows so that in the face of death we do not become fearful or despondent but in firm faith commit our souls into thy hands” (

Luther 1969, 43.197–8).

9. Concluding Remarks

Luther’s writings on the Lord’s Prayer are still a good introduction to his main ideas and they provide a window into the historical context in which those ideas developed. He clearly has fresh insights into the Prayer each time he returns to it over a period of two decades. In his earliest writing on the Prayer, he seeks to dispel any notions of our possible goodness, whereas his writings of the 1520s reflect how, as opposition increased from Catholics and other Protestants, he saw the Prayer as teaching and enabling believers to live a godly life while under attack from false teachers. His interpretations in the 1520s also show a growing concern about good government and pressing economic issues. Finally, his writings of the 1530s become more vehement against opponents and more focused on sickness and death. These interpretive changes coincide with such events as his work on translating the Bible into German in 1522, the economic and social problems of the mid 1520s and the failure both of Protestant unity and reconciliation with the Catholics by the 1530s. Nonetheless, even as the historical context changes, the Prayer continues to be a way for Luther to teach significant theological principles to his parishioners, such as the hiddenness of God, the corruption of the will, the alien and proper work of God and justification by faith alone. He intended each of the writings on the Lord’s Prayer to make complex theological concepts easily accessible to an audience of laypeople and in the case of the Large Catechism, these concepts are illustrated well by Lucas Cranach.