Kept in His Care: The Role of Perceived Divine Control in Positive Reappraisal Coping

Abstract

:1. Introduction

Let us greet with a song of hope each day,Tho’ the moments be cloudy or fair;Let us trust in our savior always,Who keepeth everyone in His care.—Ada Blenkhorn and J. Howard Entwisle, “Keep on the Sunny Side”

2. Background

2.1. Traumatic Life Events, Assumptive Worlds, and Positive Reappraisals

2.2. Perceived Divine Control as a Stress-Moderator

2.2.1. Potential Benefits: Stress-Buffering Hypothesis

2.2.2. Potential Harms: Stress-Exacerbating Hypothesis

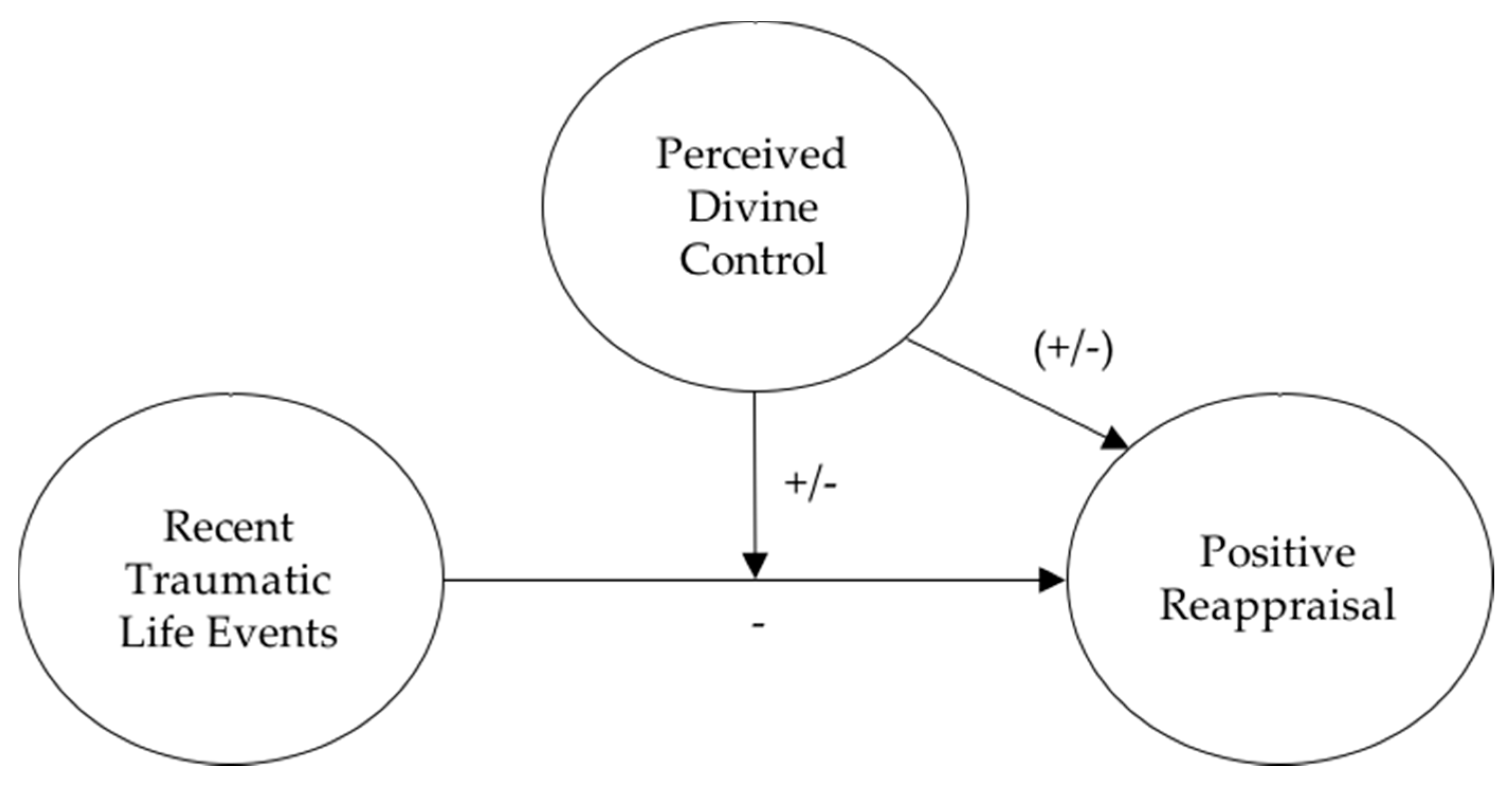

3. Summary of Hypotheses

4. Methods

4.1. Data

4.2. Measures

4.2.1. Positive Reappraisals

4.2.2. Past-Year Traumatic Life Events

4.2.3. Perceived Divine Control

4.2.4. Religious Covariates

4.2.5. Social Resources

4.2.6. Socio-Demographics

4.3. Analytic Strategy

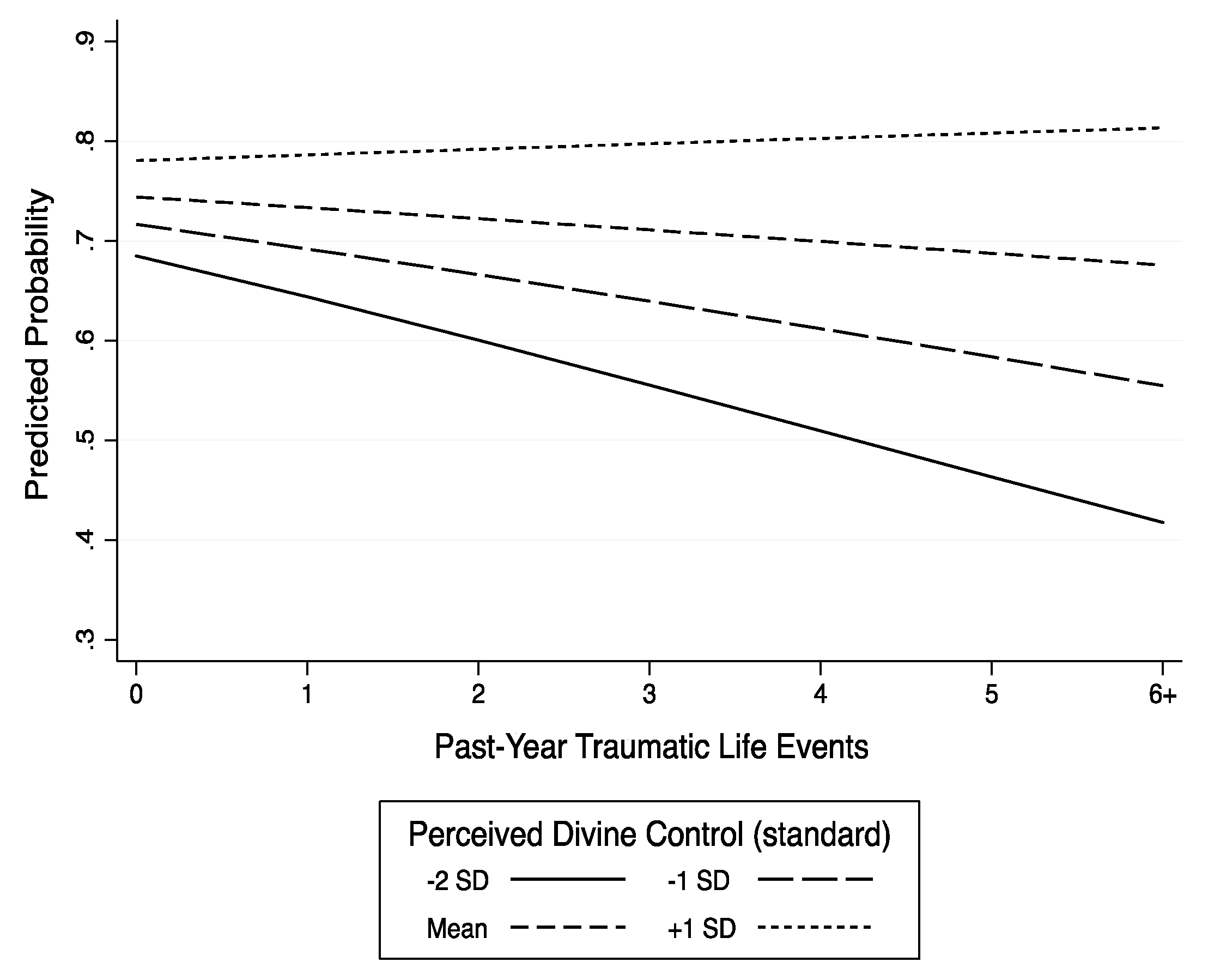

5. Results

6. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Acevedo, Gabriel A., Christopher G. Ellison, and Xiaohe Xu. 2014. Is it Really Religion? Comparing the Main and Stress-Buffering Effects of Religious and Secular Civic Engagement on Psychological Distress. Society and Mental Health 4: 111–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiken, Leona S., Stephen G. West, and Raymond R. Reno. 1991. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, Albert. 2003. On the Psychosocial Impact and Mechanisms of Spiritual Modeling. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 13: 167–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, Peter L. 1967. The Sacred Canopy. New York: Doubleday. [Google Scholar]

- Bierman, Alex. 2006. Does Religion Buffer the Effects of Discrimination on Mental Health? Differing Effects by Race. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 45: 551–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradshaw, Matt, and Christopher G. Ellison. 2010. Financial Hardship and Psychological Distress: Exploring the Buffering Effects of Religion. Social Science and Medicine 71: 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradshaw, Matt, Christopher G. Ellison, and Jack P. Marcum. 2010. Attachment to God, Images of God, and Psychological Distress in a Nationwide Sample of Presbyterians. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 20: 130–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradshaw, Matt, Christopher G. Ellison, and Kevin J. Flannelly. 2008. Prayer, God Imagery, and Symptoms of Psychopathology. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 47: 644–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brashears, Matthew E. 2010. Anomia and the Sacred Canopy: Testing a Network Theory. Social Networks 32: 187–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calhoun, Lawrence G., Arnie Cann, Richard G. Tedeschi, and Jamie McMillan. 2000. A Correlational Test of the Relationship between Posttraumatic Growth, Religion, and Cognitive Processing. Journal of Traumatic Stress 13: 521–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeAngelis, Reed T. 2017. Goal-Striving Stress and Self-Concept: The Moderating Role of Perceived Divine Control. Society and Mental Health. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durkheim, Emile. 2006. On Suicide. Translated by Robin Buss. New York: Penguin. First published in 1897. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, Albert. 1960. There is No Place for the Concept of Sin in Psychotherapy. Journal of Counseling Psychology 7: 188–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellison, Christopher G. 1991. Religious Involvement and Subjective Well-Being. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 32: 80–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellison, Christopher G., Jason D. Boardman, David R. Williams, and James S. Jackson. 2001. Religious Involvement, Stress, and Mental Health: Findings from the 1995 Detroit Area Study. Social Forces 80: 215–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellison, Christopher G., Marc A. Musick, and Andrea K. Henderson. 2008. Balm in Gilead: Racism, Religious Involvement, and Psychological Distress among African-American Adults. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 47: 291–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellison, Christopher G., Amy M. Burdette, and Terrence D. Hill. 2009. Blessed Assurance: Religion, Anxiety, and Tranquility among US Adults. Social Science Research 38: 656–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellison, Christopher G., and Jinwoo Lee. 2010. Spiritual Struggles and Psychological Distress: Is There a Dark Side of Religion? Social Indicators Research 98: 501–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellison, Christopher G., and Andrea K. Henderson. 2011. Religion and Mental Health: Through the Lens of the Stress Process. In Toward a Sociological Theory of Religion and Health. Edited by Anthony Blasi. Boston: Brill, pp. 11–44. [Google Scholar]

- Ellison, Christopher G., Scott Schieman, and Matt Bradshaw. 2014. The Association between Religiousness and Psychological Well-Being among Older Adults: Is There an Educational Gradient? In Religion and Inequality in America. Edited by Lisa A. Keister and Darren E. Sherkat. New York: Cambridge UP, pp. 263–88. [Google Scholar]

- Exline, Julie. 2002. Stumbling Blocks on the Religious Road: Fractured Relationships, Nagging Vices, and the Inner Struggle to Believe. Psychological Inquiry 13: 182–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exline, Julie Juola, Ann Marie Yali, and William C. Sanderson. 2000. Guilt, Discord, and Alienation: The Role of Religious Strain in Depression and Suicidality. Journal of Clinical Psychology 56: 1481–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flannelly, Kevin J. 2017. Religious Beliefs, Evolutionary Psychiatry, and Mental Health in America. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Foley, Daniel P. 1988. Eleven Interpretations of Personal Suffering. Journal of Religion and Health 27: 321–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frances, Bryan. 2013. Gratuitous Suffering and the Problem of Evil: A Comprehensive Introduction. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Froese, Paul, and Christopher Bader. 2010. America’s Four Gods: What We Say about God and What That Says about Us. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Galek, Kathleen, Kevin J. Flannelly, Christopher G. Ellison, and Nava R. Silton. 2015. Religion, Meaning and Purpose, and Mental Health. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 7: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garland, Eric L., Susan A. Gaylord, and Barbara L. Fredrickson. 2011. Positive Reappraisal Mediates the Stress-Reductive Effects of Mindfulness: An Upward Spiral Process. Mindfulness 2: 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garnefski, Nadia, Jeroen Legerstee, Vivian Kraaij, Tessa van Den Kommer, and Jan Teerds. 2002. Cognitive Coping Strategies and Symptoms of Depression and Anxiety: A Comparison between Adolescents and Adults. Journal of Adolescence 25: 603–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garnefski, Nadia, Jan Teerds, Vivian Kraaij, Jeroen Legerstee, and Tessa van Den Kommer. 2004. Cognitive Emotion Regulation Strategies and Depressive Symptoms: Differences between Males and Females. Personality and Individual Differences 36: 267–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granqvist, Peter, Mario Mikulincer, and Phillip R. Shaver. 2010. Religion as Attachment: Normative Processes and Individual Differences. Personality and Social Psychology Review 14: 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gray, Kurt, and Daniel M. Wegner. 2010. Blaming God for Our Pain: Human Suffering and the Divine Mind. Personality and Social Psychology Review 14: 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heckhausen, Jutta, and Richard Schulz. 1995. A Life-Span Theory of Control. Psychological Review 102: 284–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, Terrence D., Sunshine M. Rote, Christopher G. Ellison, and Amy M. Burdette. 2014. Religious Attendance and Biological Functioning: A Multiple Specification Approach. Journal of Aging and Health 26: 766–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, Terrence D., Christopher G. Ellison, Amy M. Burdette, John Taylor, and Katherine L. Friedman. 2016. Dimensions of Religious Involvement and Leukocyte Telomere Length. Social Science and Medicine 163: 168–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, Terrence D., Preeti Vaghela, Christopher G. Ellison, and Sunshine Rote. 2017. Processes Linking Religious Involvement and Telomere Length. Biodemography and Social Biology 63: 167–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Idler, Ellen L. 1995. Religion, Health, and Nonphysical Senses of Self. Social Forces 74: 683–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idler, Ellen L., Marc A. Musick, Christopher G. Ellison, Linda K. George, Neal Krause, Marcia G. Ory, Kenneth I. Pargament, Lynda H. Powell, Lynn G. Underwood, and David R. Williams. 2003. Measuring Multiple Dimensions of Religion and Spirituality for Health Research: Conceptual Background and Findings from the 1998 General Social Survey. Research on Aging 25: 327–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janoff-Bulman, Ronnie. 1989. Assumptive Worlds and the Stress of Traumatic Events: Applications of the Schema Construct. Social Cognition 7: 113–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonas, Eva, and Peter Fischer. 2006. Terror Management and Religion: Evidence that Intrinsic Religiousness Mitigates Worldview Defense Following Mortality Salience. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 91: 553–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kay, Aaron C., Danielle Gaucher, Jamie L. Napier, Mitchell J. Callan, and Kristin Laurin. 2008. God and the Government: Testing a Compensatory Control Mechanism for the Support of External Systems. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology: Attitudes and Social Cognition 95: 18–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kay, Aaron C., David A. Moscovitch, and Kristin Laurin. 2010. Randomness, Attributions of Arousal, and Belief in God. Psychological Science 21: 216–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koenig, Harold, Dana King, and Verna B. Carson. 2012. Handbook of Religion and Health, 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Krause, Neal. 1998. Neighborhood Deterioration, Religious Coping, and Changes in Health during Late Life. The Gerontologist 38: 653–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krause, Neal. 2003. Praying for Others, Financial Strain, and Physical Health Status in Late Life. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 42: 377–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, Neal. 2005. God-Mediated Control and Psychological Well-Being in Late Life. Research on Aging 27: 136–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, Neal. 2009. Religious Involvement, Gratitude, and Change in Depressive Symptoms over Time. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 19: 155–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krause, Neal. 2010. God-Mediated Control and Change in Self-Rated Health. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 20: 267–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krause, Neal. 2011. Religion and Health: Making Sense of a Disheveled Literature. Journal of Religion and Health 50: 20–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krause, Neal, and Keith M. Wulff. 2004. Religious Doubt and Health: Exploring the Potential Dark Side of Religion. Sociology of Religion 65: 35–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, Neal, and Elena Bastida. 2011. Social Relationships in the Church during Late Life: Assessing Differences between African Americans, Whites, and Mexican Americans. Review of Religious Research 53: 41–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazarus, Richard S., and Raymond Launier. 1978. Stress-Related Transactions between Person and Environment. In Perspectives in Interactional Psychology. New York: Springer, pp. 287–327. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus, Richard S., and Susan Folkman. 1984. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Lerner, Melvin J. 1980. The Belief in a Just World: A Fundamental Delusion. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Levin, Jeff. 2017. ‘For They Knew Not What It Was’: Rethinking the Tacit Narrative History of Religion and Health Research. Journal of Religion and Health 56: 28–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McIntosh, Daniel N. 1995. Religion-As-Schema, With Implications for the Relation between Religion and Coping. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 5: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McRae, Kateri. 2013. Emotion Regulation Frequency and Success: Separating Constructs from Methods and Time Scale. Social and Personality Psychology Compass 7: 289–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norenzayan, Ara. 2013. Big Gods: How Religion Transformed Cooperation and Conflict. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pargament, Kenneth I. 1997. The Psychology of Religion and Coping: Theory, Research, Practice. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pargament, Kenneth I. 2002. The Bitter and the Sweet: An Evaluation of the Costs and Benefits of Religiousness. Psychological Inquiry 13: 168–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pargament, Kenneth I., and June Hahn. 1986. God and the Just World: Causal and Coping Attributions to God in Health Situations. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 25: 193–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pargament, Kenneth I., Joseph Kennell, William Hathaway, Nancy Grevengoed, Jon Newman, and Wendy Jones. 1988. Religion and the Problem-Solving Process: Three Styles of Coping. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 27: 90–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pargament, Kenneth I., Bruce W. Smith, Harold G. Koenig, and Lisa Perez. 1998. Patterns of Positive and Negative Religious Coping with Major Life Stressors. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 37: 710–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkes, C. Murray. 1971. Psycho-Social Transitions: A Field for Study. Social Science and Medicine 5: 101–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearlin, Leonard I., and Carmi Schooler. 1978. The Structure of Coping. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 19: 2–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearlin, Leonard I. 1989. The Sociological Study of Stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 30: 241–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plantinga, Alvin. 1974. God, Freedom, and Evil. Grand Rapids: Harper and Row. [Google Scholar]

- Pollner, Melvin. 1989. Divine Relations, Social Relations, and Well-Being. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 30: 92–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Religious Landscape Study. 2014. Washington: Pew Research Center. Available online: http://www.pewforum.org/religious-landscape-study/ (accessed on 12 April 2017).

- Rothbaum, Fred, John R. Weisz, and Samuel S. Snyder. 1982. Changing the World and Changing the Self: A Two-Process Model of Perceived Control. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 42: 5–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, Carol D., and Burton Singer. 2003. Flourishing Under Fire: Resilience as a Prototype of Challenged Thriving. In Flourishing: Positive Psychology and the Life Well-Lived. Edited by Corey L. M. Keyes and Jonathan Haidt. Washington: American Psychological Association, pp. 15–36. [Google Scholar]

- Schieman, Scott. 2008. The Education-Contingent Association between Religiosity and Health: The Differential Effects of Self-Esteem and the Sense of Mastery. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 47: 710–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schieman, Scott. 2010. Socioeconomic Status and Beliefs about God’s Influence in Everyday Life. Sociology of Religion 71: 25–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schieman, Scott, and Alex Bierman. 2011. The Role of Divine Beliefs in Stress Processes. In Toward a Sociological Theory of Religion and Health. Edited by Anthony Blasi. Leiden: Brill, pp. 45–68. [Google Scholar]

- Schieman, Scott, Tetyana Pudrovska, and Melissa A. Milkie. 2005. The Sense of Divine Control and the Self-Concept: A Study of Race Differences in Late Life. Research on Aging 27: 165–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schieman, Scott, Tetyana Pudrovska, Leonard I. Pearlin, and Christopher G. Ellison. 2006. The Sense of Divine Control and Psychological Distress: Variations across Race and Socioeconomic Status. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 45: 529–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sears, Sharon R., Annette L. Stanton, and Sharon Danoff-Burg. 2003. The Yellow Brick Road and the Emerald City: Benefit Finding, Positive Reappraisal Coping, and Posttraumatic Growth in Women with Early-Stage Breast Cancer. Health Psychology 22: 487–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spilka, Bernard, James Addison, and Marguerite Rosensohn. 1975. Parents, Self, and God: A Test of the Competing Theories of Individual-Religion Relationships. Review of Religious Research 16: 154–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroope, Samuel, Scott Draper, and Andrew L. Whitehead. 2013. Images of a Loving God and Sense of Meaning in Life. Social Indicators Research 111: 25–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swann, William B., and Michael D. Buhrmester. 2012. Self as Functional Fiction. Social Cognition 30: 415–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tillich, Paul. 1957. Dynamics of Faith. New York: Harper and Row. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, Shelley E., and Annette L. Stanton. 2007. Coping Resources, Coping Processes, and Mental Health. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology 3: 377–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, R. Jay, Blair Wheaton, and Donald A. Lloyd. 1995. The Epidemiology of Social Stress. American Sociological Review 60: 104–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umezawa, Yoshiko, Qian Lu, Jin You, Marjorie Kagawa-Singer, Barbara Leake, and Rose C. Maly. 2012. Belief in Divine Control, Coping, and Race/Ethnicity among Older Women with Breast Cancer. Annals of Behavioral Medicine 44: 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vail, Kenneth E., Zachary K. Rothschild, Dave R. Weise, Sheldon Solomon, Tom Pyszczynski, and Jeff Greenberg. 2010. Terror Management Analysis of the Psychological Functions of Religion. Personality and Social Psychology Review 14: 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vishkin, Allon, Yochana E. Bigman, Roni Porat, Nevin Solak, Eran Halperin, and Maya Tamir. 2016. God Rest Our Hearts: Religiosity and Cognitive Reappraisal. Emotion 16: 252–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wheaton, Blair. 1985. Models for the Stress-Buffering Functions of Coping Resources. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 26: 352–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, Robert W. 1959. Motivation Reconsidered: The Concept of Competence. Psychological Review 66: 297–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, Ian R., Patrick Royston, and Angela M. Wood. 2011. Multiple Imputation Using Chained Equations: Issues and Guidance for Practice. Statistics in Medicine 30: 377–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wikström, Owe. 1987. Attribution, Roles and Religion: A Theoretical Analysis of Sunden’s Role Theory of Religion and the Attributional Approach to Religious Experience. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 26: 390–400. [Google Scholar]

- Wrosch, Carsten, Jutta Heckhausen, and Margie E. Lachman. 2000. Primary and Secondary Control Strategies for Managing Health and Financial Stress Across Adulthood. Psychology and Aging 15: 387–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| 1 | Some scholars have chosen to distinguish between frequency versus efficacy of using positive reappraisal coping (e.g., (McRae 2013)). To clarify, our measure gauges one’s capacity or efficacy of using positive reappraisal coping, rather than the frequency at which one uses positive reappraisal coping. This distinction is important because we might reasonably expect respondents who have experienced more recent traumatic life events to report a greater frequency of using positive reappraisal coping. Our stress process conceptual model basically assumes that traumatic life events should undermine one’s positive reappraisal coping skills, or ability to effectively use positive reappraisal coping for regulating negative emotions. |

| Range | Mean (%) | SD | α | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Focal Variables | ||||

| Positive reappraisals | 1–3 | 2.03 | 0.78 | 0.74 |

| Past-year traumatic life events | 0–6 | 2.07 | 1.78 | |

| Perceived divine control | 1–4 | 2.92 | 0.80 | 0.83 |

| Religious Covariates | ||||

| Religious attendance | 0–6 | 3.03 | 2.24 | |

| Prayer | 1–6 | 4.39 | 1.65 | |

| Religious/spiritual coping | 1–5 | 3.69 | 1.29 | |

| Religious social support | 1–4 | 1.80 | 0.99 | |

| Social Resources | ||||

| Family cohesion | 1–4 | 3.18 | 0.67 | 0.90 |

| Friend support | 1–4 | 3.33 | 0.74 | 0.95 |

| Socio-demographics | ||||

| Age | 22–69 | 44.32 | 11.72 | |

| Female | 0–1 | (52) | ||

| Male (reference) | 0–1 | (48) | ||

| Black | 0–1 | (28) | ||

| Non-Hispanic white (reference) | 0–1 | (72) | ||

| Married | 0–1 | (57) | ||

| Not married (reference) | 0–1 | (43) | ||

| Education (in years) | 0–28 | 14.49 | 3.02 | |

| Employed full-time | 0–1 | (63) | ||

| Unemployed/employed part-time (reference) | 0–1 | (37) | ||

| Household income | 0–15 | 8.88 | 3.97 | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Focal Associations | |||||

| Past-year traumatic life events | −0.062 ** | −0.052 ** | −0.062 ** | −0.054 ** | |

| Perceived divine control | 0.461 ** | 0.467 ** | 0.203 | 0.203 | |

| Life events × Divine control | 0.104 * | 0.098 * | 0.087 * | ||

| Religious Covariates | |||||

| Religious attendance | −0.086 | −0.089 | |||

| Prayer | 0.071 | 0.058 | |||

| Religious/spiritual coping | 0.256 *** | 0.294 *** | |||

| Religious social support | 0.056 | −0.010 | |||

| Social Resources | |||||

| Family cohesion | 0.163 * | ||||

| Friend support | 0.454 *** | ||||

| Socio-demographics | |||||

| Age | −0.006 | −0.007 | −0.010 | −0.009 | |

| Female | 0.068 | 0.058 | −0.019 | −0.129 | |

| Black | −0.012 | −0.006 | −0.012 | 0.028 | |

| Married | −0.220 | −0.219 | −0.245 * | −0.236 ** | |

| Education | −0.001 | −0.001 | −0.007 | −0.019 | |

| Employed full-time | 0.041 | 0.041 | 0.030 | 0.020 | |

| Household income | 0.073 * | 0.073 * | 0.086 ** | 0.070 * | |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

DeAngelis, R.T.; Ellison, C.G. Kept in His Care: The Role of Perceived Divine Control in Positive Reappraisal Coping. Religions 2017, 8, 133. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel8080133

DeAngelis RT, Ellison CG. Kept in His Care: The Role of Perceived Divine Control in Positive Reappraisal Coping. Religions. 2017; 8(8):133. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel8080133

Chicago/Turabian StyleDeAngelis, Reed T., and Christopher G. Ellison. 2017. "Kept in His Care: The Role of Perceived Divine Control in Positive Reappraisal Coping" Religions 8, no. 8: 133. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel8080133