Measuring Symptoms of Moral Injury in Veterans and Active Duty Military with PTSD

Abstract

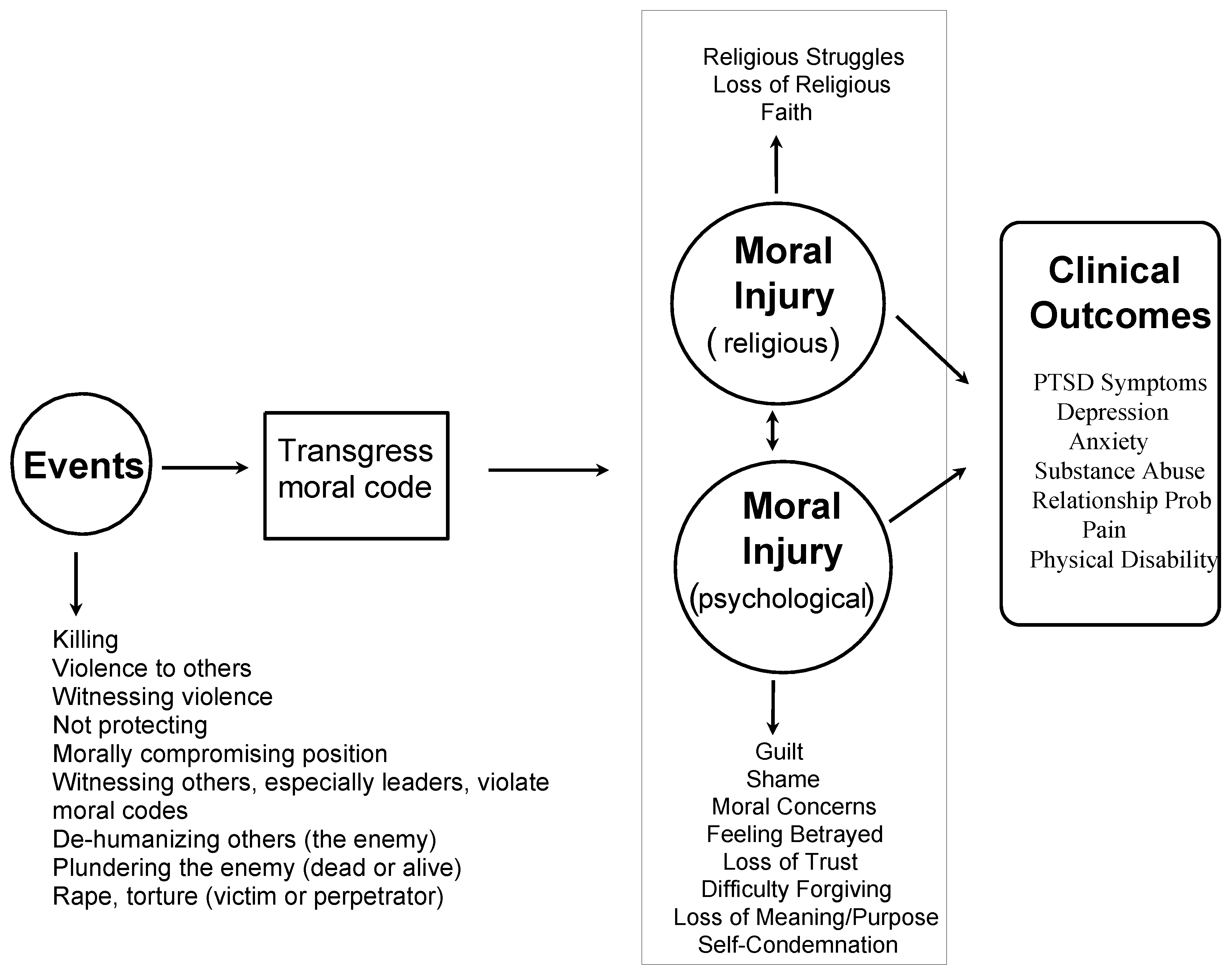

:1. Introduction

2. Measurement

Objectives

3. Development of the Moral Injury Symptom Scale-Military Version (MISS-M)

3.1. Guilt

3.2. Shame

3.3. Betrayal

3.4. Violation of Moral Values

3.5. Loss of Meaning

3.6. Difficulty Forgiving

3.7. Loss of Trust

3.8. Self-Condemnation

3.9. Spiritual/Religious Struggles

3.10. Loss of Religious Faith/Hope

4. Psychometric Properties of the MISS-M

4.1. Factor Analysis

4.2. Reliability

4.3. Validity

5. Prevalence of Moral Injury Symptoms

6. Limitations

7. Clinical and Research Applications of the MISS-M

7.1. Clinical Applications

7.2. Research Applications

8. Conclusions

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Ai, Amy L., E. Mitchell Seymour, Terrence N. Tice, Ziad Kronfol, and Steven F. Bolling. 2009. Spiritual struggle related to plasma interleukin-6 prior to cardiac surgery. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 1: 112–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. 2013. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5®). Arlington: American Psychiatric Association Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, Bernice, Chris R. Brewin, Lorna Stewart, Rosanna Philpott, and Jennie Hejdenberg. 2009. Comparison of immediate-onset and delayed-onset posttraumatic stress disorder in military veterans. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 118: 767–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brock, Rita Nakashima, and Gabriella Lettini. 2012. Soul Repair: Recovering from Moral Injury after War. Boston: Beacon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bryan, Craig J., AnnaBelle O. Bryan, Michael D. Anestis, Joye C. Anestis, Bradley A. Green, Neysa Etienne, Chad E. Morrow, and Bobbie Ray-Sannerud. 2016. Measuring moral injury: Psychometric properties of the Moral Injury Events Scale in two military samples. Assessment 23: 557–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarke, David. 2003. Faith and hope. Australasian Psychiatry 11: 164–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronbach, Lee J. 1951. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 16: 297–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currier, Joseph M., Kent D. Drescher, and J. Irene Harris. 2014. Spiritual functioning among veterans seeking residential treatment for PTSD: A matched control group study. Spirituality in Clinical Practice 1: 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currier, Joseph M., Jason M. Holland, and Kent D. Drescher. 2015a. Spirituality factors in the prediction of outcomes of PTSD treatment for U.S. military veterans. Journal of Traumatic Stress 28: 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Currier, Joseph M., Jason M. Holland, Kent Drescher, and David Foy. 2015b. Initial psychometric evaluation of the moral injury questionnaire—Military Version. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy 22: 54–63. [Google Scholar]

- Drescher, Kent D., David W. Foy, Caroline Kelly, Anna Leshner, Kerrie Schutz, and Brett Litz. 2011. An exploration of the viability and usefulness of the construct of moral injury in war veterans. Traumatology 17: 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbogen, Eric B., H. Ryan Wagner, Nathan A. Kimbrel, Mira Brancu, Jennifer Naylor, Robert Graziano, and Eric Crawford. 2017. Risk factors for concurrent suicidal ideation and violent impulses in military veterans. Psychological Assessment. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flipse Vargas, Alison, Thomas Hanson, Douglas Kraus, Kent Drescher, and David Foy. 2013. Moral injury themes in combat veterans’ narrative responses from the National Vietnam Veterans’ Readjustment Study. Traumatology 19: 243–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontana, Alan, and Robert Rosenheck. 2004. Trauma, change in strength of religious faith, and mental health service use among veterans treated for PTSD. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 192: 579–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fontana, Alan, and Robert Rosenheck. 2005. The role of loss of meaning in the pursuit of treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress 18: 133–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedman, Matthew J. 1981. Post-Vietnam syndrome: Recognition and management. Psychosomatics 22: 931–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulton, Jessica J., Patrick S. Calhoun, H. Ryan Wagner, Amie R. Schry, Lauren P. Hair, Nicole Feeling, Eric Elbogen, and Jean C. Beckham. 2015. The prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder in Operation Enduring Freedom/Operation Iraqi Freedom (OEF/OIF) Veterans: A meta-analysis. Journal of Anxiety Disorders 31: 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ginzburg, Karni, Tsachi Ein-Dor, and Zahava Solomon. 2010. Comorbidity of posttraumatic stress disorder, anxiety and depression: A 20-year longitudinal study of war veterans. Journal of Affective Disorders 123: 249–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, J. Irene, Christopher R. Erbes, Brian E. Engdahl, Paul Thuras, Nichole Murray-Swank, Dixie Grace, and Henry Ogden. 2011. The effectiveness of a trauma focused spiritually integrated intervention for veterans exposed to trauma. Journal of Clinical Psychology 67: 425–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendin, Herbert, and Ann Pollinger Haas. 1991. Suicide and guilt as manifestations of PTSD in Vietnam combat veterans. American Journal of Psychiatry 148: 586–91. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Henning, Kris R., and B. Christopher Frueh. 1997. Combat guilt and its relationship to PTSD symptoms. Journal of Clinical Psychology 53: 801–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoge, Charles W., and Christopher H. Warner. 2014. Estimating PTSD prevalence in US veterans: Considering combat exposure, PTSD checklist cutpoints, and DSM-5. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 75: 1439–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, W. Brad. 2014. The morally-injured veteran: Some ethical considerations. Spirituality in Clinical Practice 1: 16–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, Henry F. 1991. Coefficient alpha for a principal component and the Kaiser-Guttman Rule. Psychological Reports 68: 855–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karairmak, Ozlem, and Berna Guloglu. 2014. Forgiveness and PTSD among veterans: The mediating role of anger and negative affect. Psychiatry Research 219: 536–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koenig, Harold George, Dana King, and Verna B. Carson. 2012. Handbook of Religion and Health, 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig, Harold G., Nathan A. Boucher, Rev John P. Oliver, Nagy Youssef, Scott R. Mooney, Joseph M. Currier, and Michelle Pearce. 2017. Rationale for spiritually oriented cognitive processing therapy for moral injury in active duty military and veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 205: 147–53. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Koenig, Harold G., Donna Ames, Nagy A. Youssef, John P. Oliver, Fred Volk, Ellen J. Teng, Kerry Haynes, Zachary D. Erickson, Irina Arnold, Keisha O’Garo, and Michelle Pearce. 2018a. The Moral Injury Symptom Scale—Military Version. Journal of Religion and Health 57: 249–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koenig, Harold G., Donna Ames, Nagy A. Youssef, John P. Oliver, Fred Volk, Ellen J. Teng, Kerry Haynes, Zachary D. Erickson, Irina Arnold, Keisha O’Garo, and Michelle Pearce. 2018b. Screening for moral injury: The Moral Injury Symptom Scale – Military Version Short Form. Military Medicine. in press. [Google Scholar]

- Kopacz, Marek S., April L. Connery, Todd M. Bishop, Craig J. Bryan, Kent D. Drescher, Joseph M. Currier, and Wilfred R. Pigeon. 2016. Moral injury: A new challenge for complementary and alternative medicine. Complementary Therapies in Medicine 24: 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lane, Marian E., Laurel L. Hourani, Robert M. Bray, and Jason Williams. 2012. Prevalence of perceived stress and mental health indicators among reserve-component and active-duty military personnel. American Journal of Public Health 102: 1213–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Deborah A., Peter Scragg, and Stuart Turner. 2001. The role of shame and guilt in traumatic events: A clinical model of shame-based and guilt-based PTSD. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice 74: 451–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, Helen B. 1971. Shame and guilt in neurosis. Psychoanalytic Review 58: 419–38. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Litz, Brett T., Nathan Stein, Eileen Delaney, Leslie Lebowitz, William P. Nash, Caroline Silva, and Shira Maguen. 2009. Moral injury and moral repair in war veterans: A preliminary model and intervention strategy. Clinical Psychology Reviews 29: 695–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Litz, Brett T., Leslie Lebowitz, Matt J. Gray, and William P. Nash. 2017. Adaptive Disclosure: A New Treatment for Military Trauma, Loss, and Moral Injury. New York: Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Maguen, Shira, and Kristine Burkman. 2013. Combat-related killing: Expanding evidence-based treatments for PTSD. Cognive and Behavioral Practice 20: 476–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguen, S., and Brett Litz. 2012. Moral injury in veterans of war. PTSD Research Quarterly 23: 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- McKinney, Jessica M., Jameson K. Hirsch, and Peter C. Britton. 2017. PTSD symptoms and suicide risk in veterans: Serial indirect effects via depression and anger. Journal of Affective Disorders 214: 100–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nash, William P., Teresa L. Marino Carper, Mary Alice Mills, Teresa Au, Abigail Goldsmith, and Brett T. Litz. 2013. Psychometric evaluation of the Moral Injury Events Scale. Military Medicine 178: 646–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pargament, Kenneth I., Bruce W. Smith, Harold G. Koenig, and Lisa Perez. 1998. Patterns of positive and negative religious coping with major life stressors. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 37: 710–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pargament, Kenneth I., Harold G. Koenig, Nalini Tarakeshwar, and June Hahn. 2001. Religious struggle as a predictor of mortality among medically ill elderly patients: A two-year longitudinal study. Archives of Internal Medicine 161: 1881–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul, Lisa A., Daniel F. Gros, Martha Strachan, Glenna Worsham, Edna B. Foa, and Ron Acierno. 2014. Prolonged exposure for guilt and shame in a veteran of Operation Iraqi Freedom. American Journal of Psychotherapy 68: 277–86. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pearce, Michelle, Kerry Haynes, Natalia R. Rivera, and Harold G. Koenig. 2018. Spiritually-integrated cognitive processing therapy: A new treatment for moral injury in the setting of PTSD. Global Advances in Health and Medicine 7: 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pietrzak, Robert H., Risë B. Goldstein, Steven M. Southwick, and Bridget F. Grant. 2011. Prevalence and Axis I comorbidity of full and partial posttraumatic stress disorder in the United States: Results from Wave 2 of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Journal of Anxiety Disorders 25: 456–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramsawh, Holly J., Carol S. Fullerton, Holly B. Herberman Mash, Tsz Hin H. Ng, Ronald C. Kessler, Murray B. Stein, and Robert J. Ursano. 2014. Risk for suicidal behaviors associated with PTSD, depression, and their comorbidity in the US Army. Journal of Affective Disorders 161: 116–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenberg, Morris. 1965. Society and the Adolescent Self-Image. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shay, Jonathan. 1994. Achilles in Vietnam: Combat Trauma and the Undoing of Character. New York: Scribner. [Google Scholar]

- Shay, Jonathan. 2014. Moral injury. Psychoanalytic Psychology 31: 182–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrout, Patrick E., and Joseph L. Fleiss. 1979. Intraclass correlations: Uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychological Bulletin 86: 420–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steenkamp, Maria M., Brett T. Litz, Matt J. Gray, Leslie Lebowitz, William Nash, Lauren Conoscenti, Amy Amidon, and Ariel Lang. 2011. A brief exposure-based intervention for service members with PTSD. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice 18: 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenkamp, Maria M., Brett T. Litz, Charles W. Hoge, and Charles R. Marmar. 2015. Psychotherapy for military-related PTSD: A review of randomized clinical trials. JAMA 314: 489–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steger, Michael F., Patricia Frazier, Shigehiro Oishi, and Matthew Kaler. 2006. The Meaning in Life Questionnaire: Assessing the presence of and search for meaning in life. Journal of Counseling Psychology 53: 80–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinert, Christiane, Mareike Hofmann, Falk Leichsenring, and Johannes Kruse. 2015. The course of PTSD in naturalistic long-term studies: High variability of outcomes. A systematic review. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry 69: 483–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, Laura Yamhure, Charles R. Snyder, Lesa Hoffman, Scott T. Michael, Heather N. Rasmussen, Laura S. Billings, Laura Heinze, Jason E. Neufeld, Hal S. Shorey, Jessica C. Roberts, and et al. 2005. Dispositional forgiveness of self, others, and situations. Journal of Personality 73: 313–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weathers, Frank W., Brett T. Litz, Terence M. Keane, Patrick A. Palmieri, Brian P. Marx, and Paula P. Schnurr. 2013. The PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5) (2013). Scale Available from the National Center for PTSD. Available online: www.ptsd.va.gov (accessed on 14 June 2017).

- Witvliet, Charlotte V. O., Karl A. Phipps, M. E. Feldman, and Jean C. Beckham. 2004. Posttraumatic mental and physical health correlates of forgiveness and religious coping in military veterans. Journal of Traumatic Stress 17: 269–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Worthington, Everett L., Jr., and Diane Langberg. 2012. Religious considerations and self-forgiveness in treating complex trauma and moral injury in present and former soldiers. Journal of Psychology and Theology 40: 274–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamagishi, Toshio, and Midori Yamagishi. 1994. Trust and commitment in the United States and Japan. Motivation and Emotion 18: 129–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zigmond, Anthony S., and R. Philip Snaith. 1983. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 67: 361–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Koenig, H.G. Measuring Symptoms of Moral Injury in Veterans and Active Duty Military with PTSD. Religions 2018, 9, 86. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9030086

Koenig HG. Measuring Symptoms of Moral Injury in Veterans and Active Duty Military with PTSD. Religions. 2018; 9(3):86. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9030086

Chicago/Turabian StyleKoenig, Harold G. 2018. "Measuring Symptoms of Moral Injury in Veterans and Active Duty Military with PTSD" Religions 9, no. 3: 86. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9030086