Who Leads Advocacy through Social Media in Japan? Evidence from the “Tsukuba Civic Activities Cyber-Square” Facebook Page

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review: Advocacy Activities by Civil Society Organizations in Japan

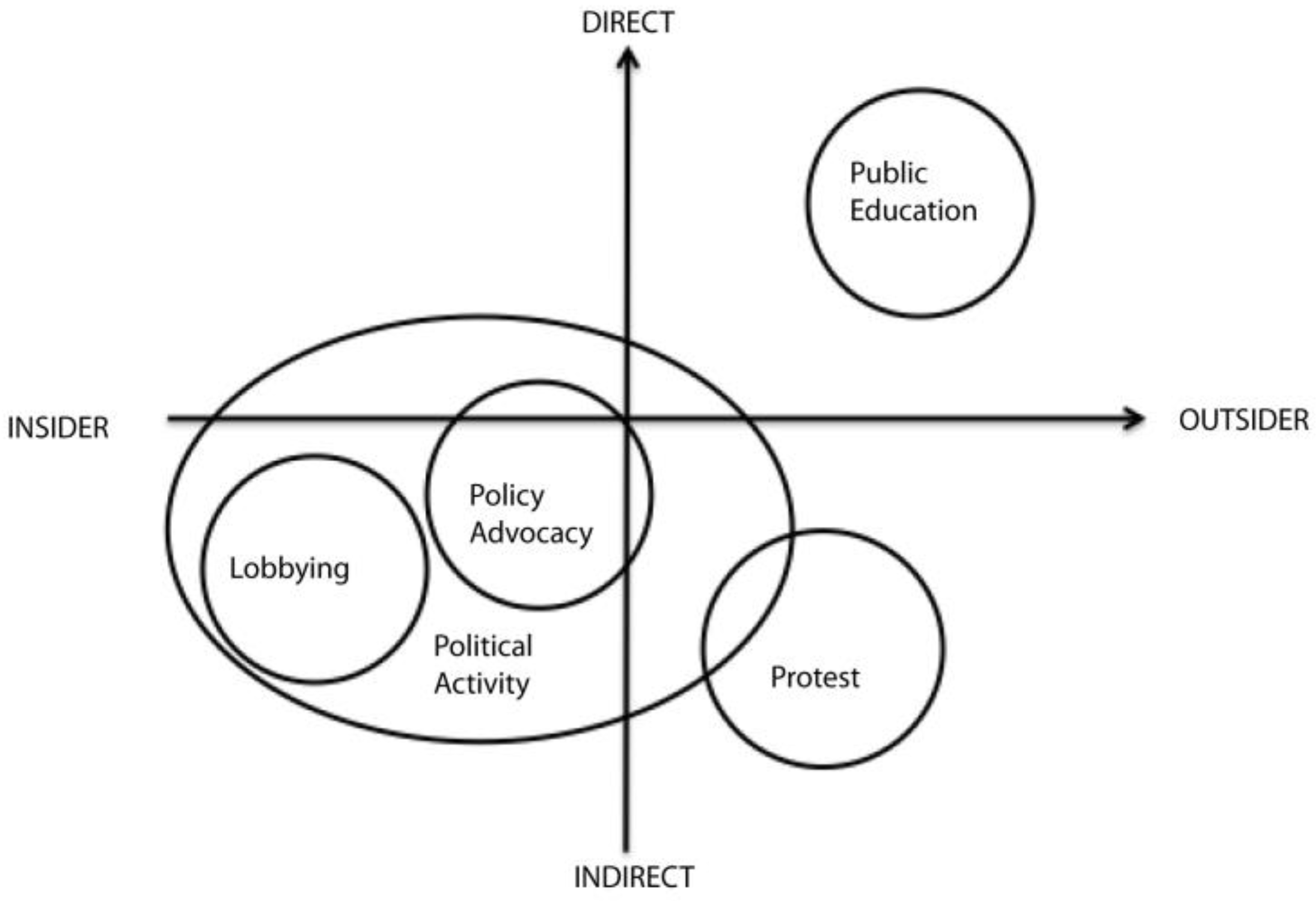

2.1. Definition of Advocacy

2.2. Who Advocates? Japan’s “CSOs” through a Comparative Perspective

2.3. Advocacy and Media in Japan

3. Research Design and Methodology

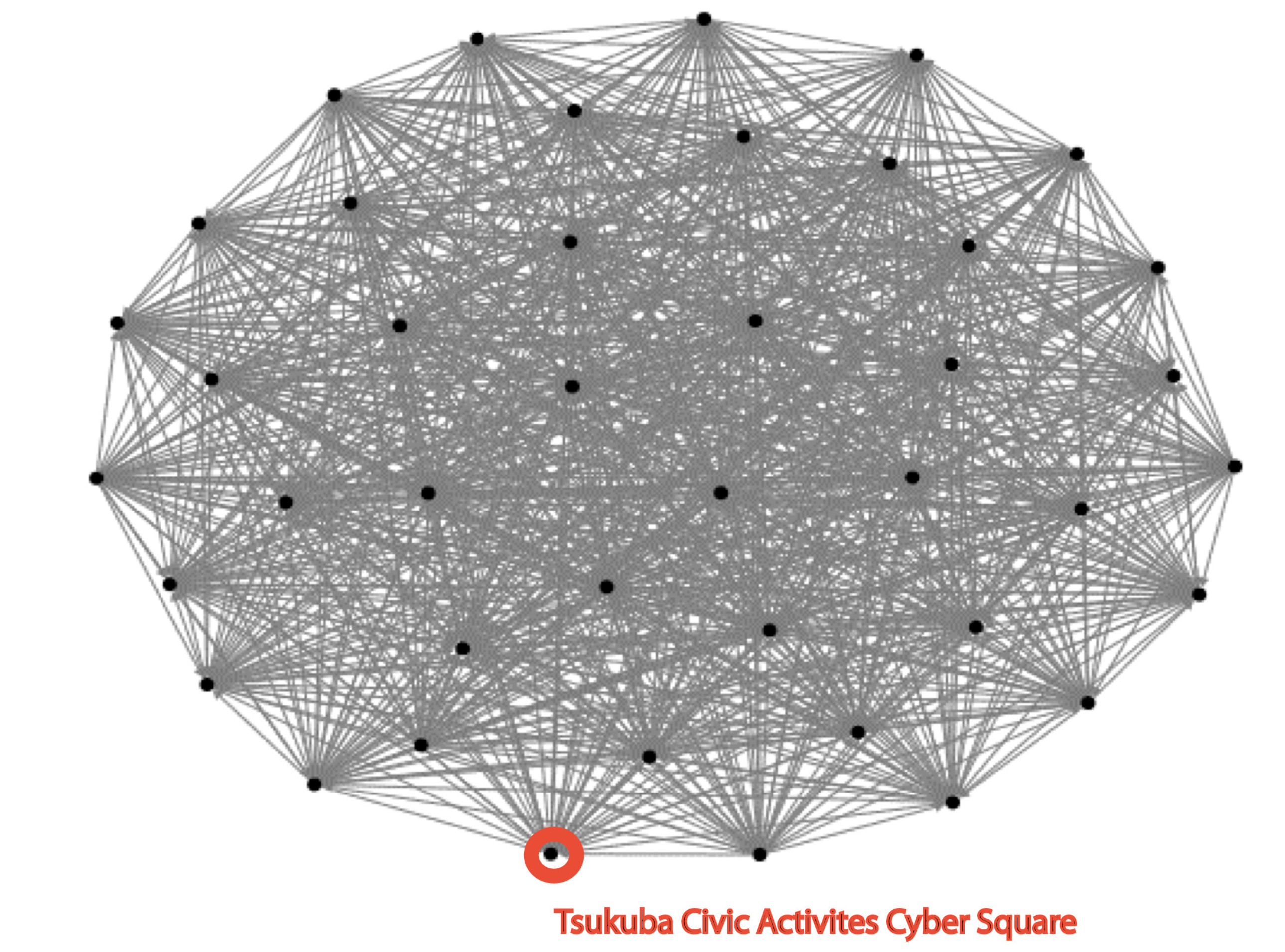

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. Users of the Tsukuba Civic Activities Cyber-Square

3.3. Methodology

4. Results

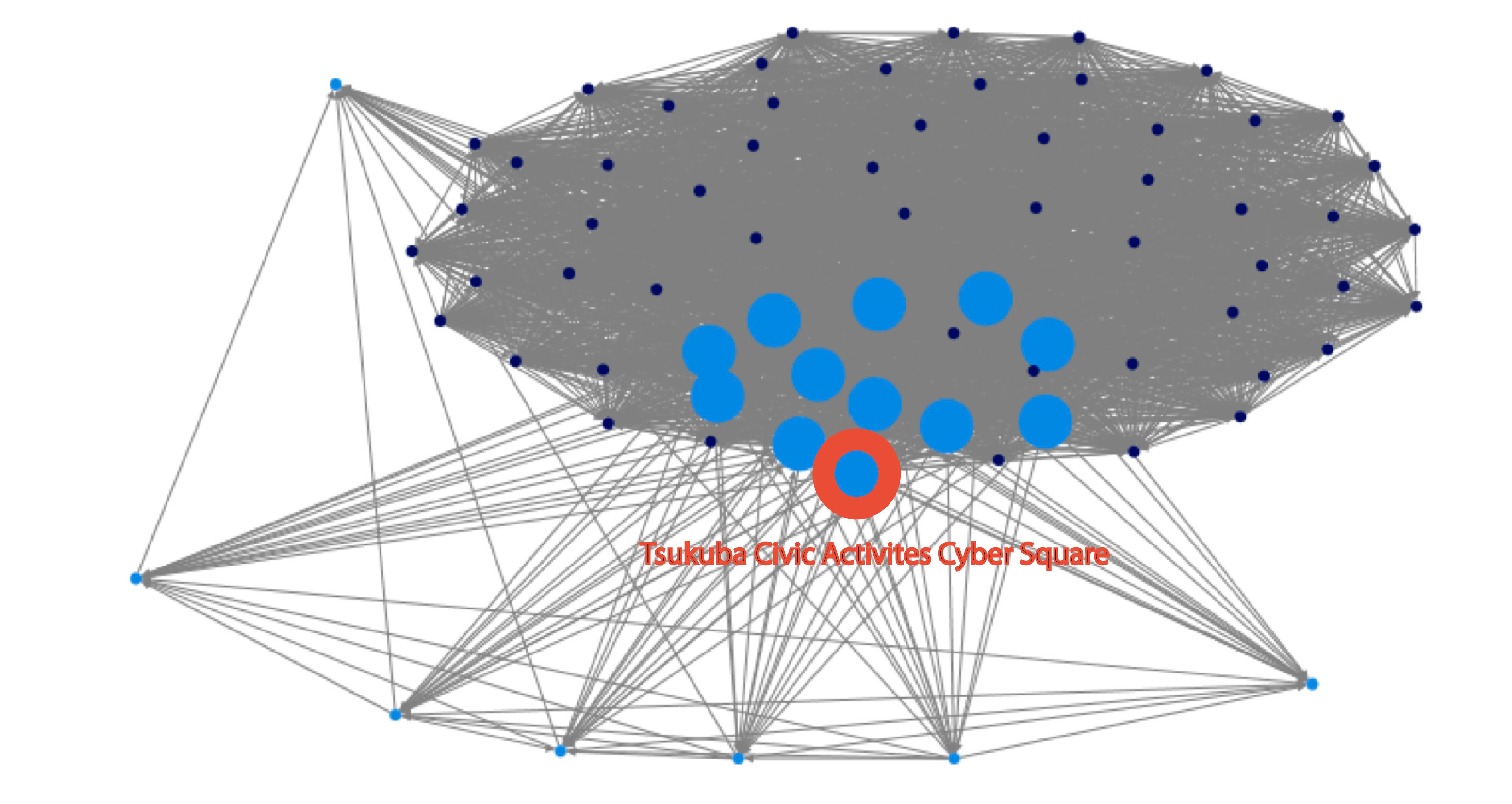

4.1. Neighborhood Association (NHA) Networks

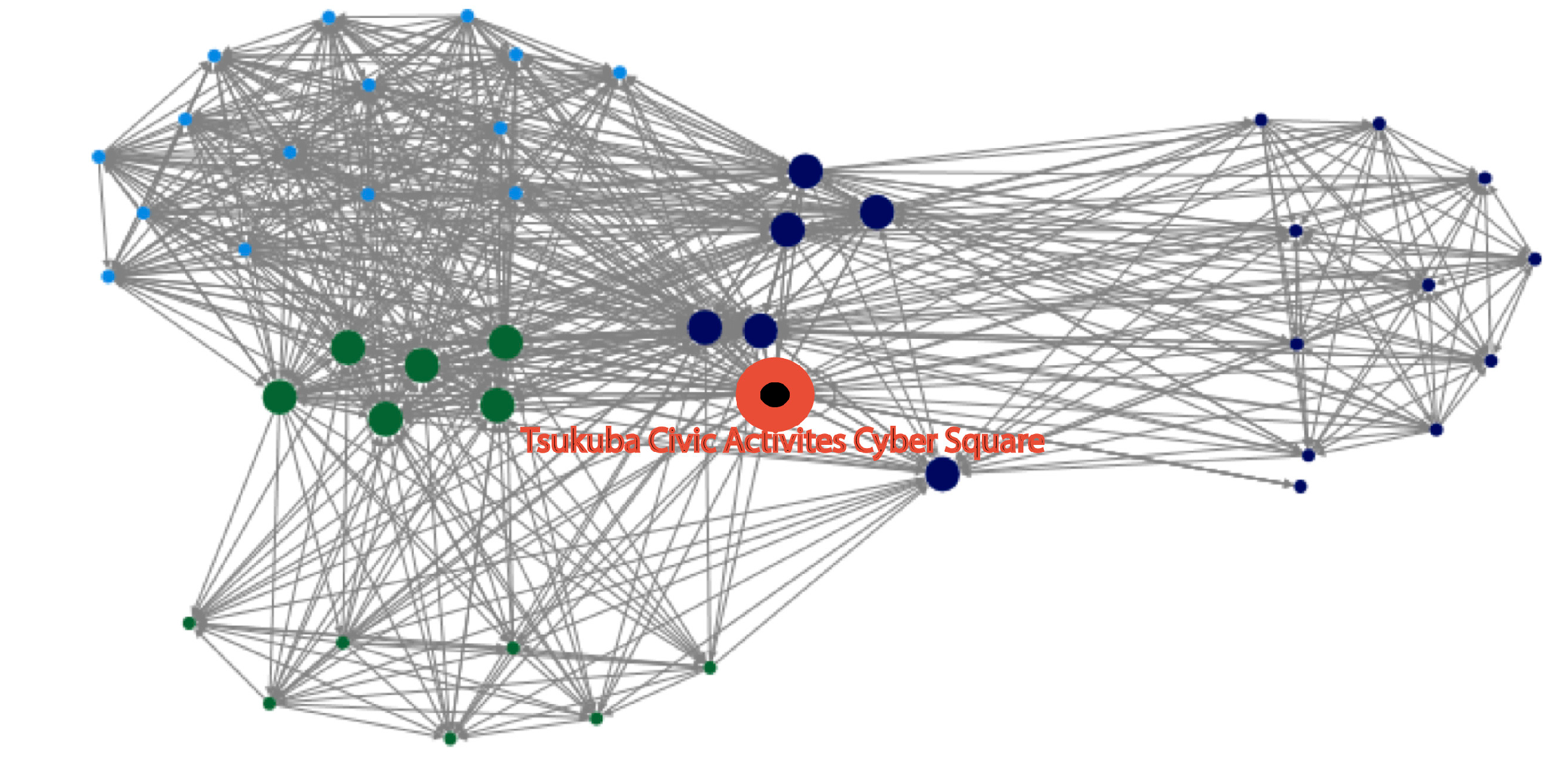

4.2. Disaster Networks

4.3. Social Welfare Networks

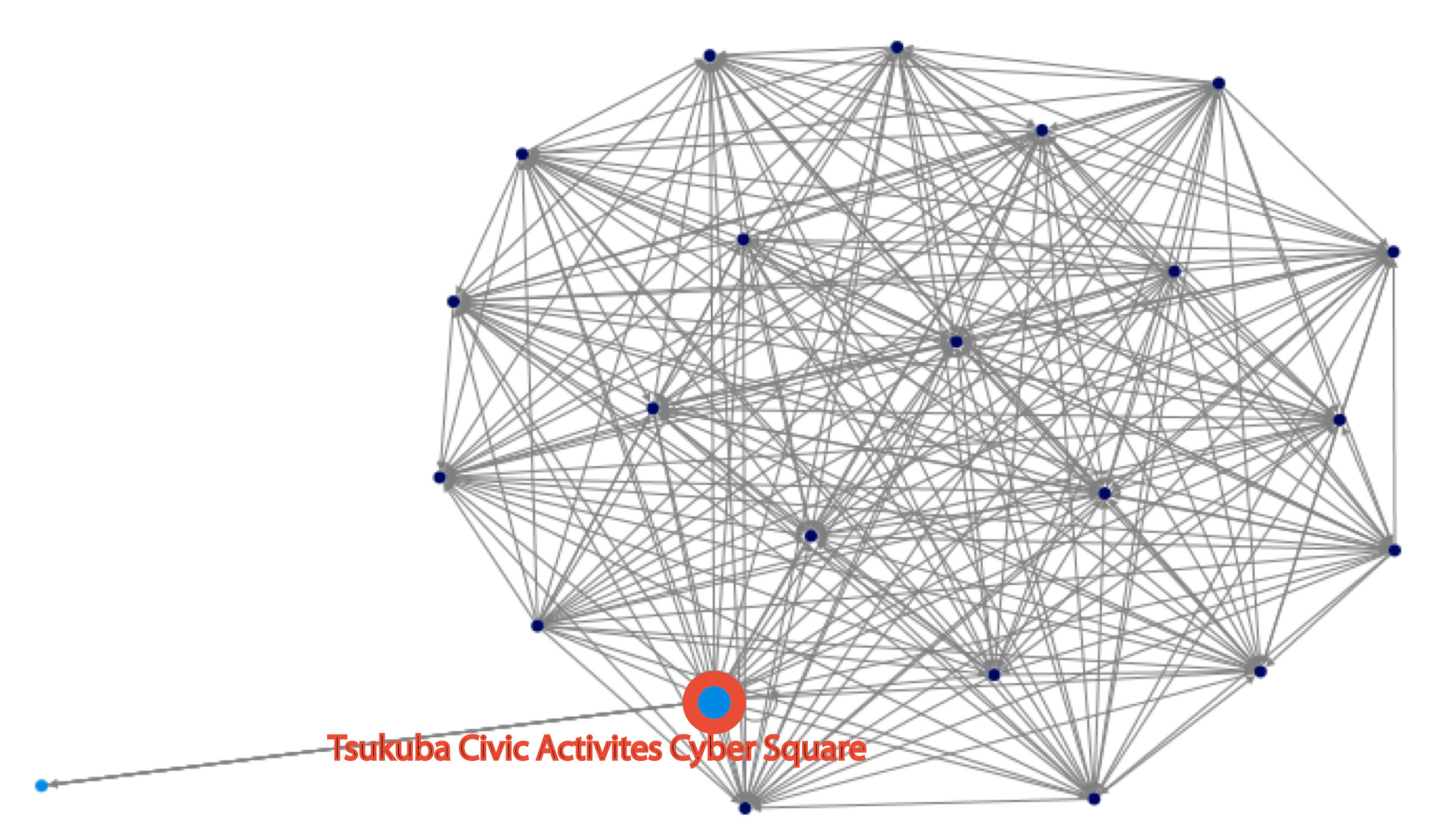

4.4. Volunteer Networks

4.5. Summary of Analysis and Comparison

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| 1 | Launch Time of the Facebook Page | 1 February 2012 |

| 2 | Facebook group page manager | Division for volunteering support policy of the municipal government of Tsukuba, Ibaraki, Japan |

| 3 | Main target area | Tsukuba, Ibaraki, Japan |

| 4 | Objectives | To activate social network within a community and promote more civic engagement by developing information infrastructures |

| 5 | Accumulated “Likes” of the Facebook page (as of 17 April 2016) | 2604 |

| 6 | Gender of users by age (as of 17 April 2016) | −24: women 3%, men 4% |

| 25–34: women 11%, men 14% | ||

| 35–44: women 12%, men 20% | ||

| 45–54: women 8%, men 13% | ||

| 55–64: women 3%, men 6% | ||

| 65+: women 1%, men 4% | ||

| 7 | Residential Profiles of users (as of 27 January 2014) | Tsukuba, Ibaraki, Japan: 54.2% |

| Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo, Japan: 8.7% | ||

| Tsuchiura, Ibaraki, Japan: 4.4% | ||

| Mito, Ibaraki, Japan 2.9% | ||

| etc. |

Appendix B

| NHA (12 June 2015) | Tornado in Hojo, Ibaraki (12 June 2012) | Social Welfare (25 January 2016) | Volunteering (28 January 2016) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum Betweenness Centrality | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Maximum Betweenness Centrality | 63 | 220.176 | 42 | 0 |

| Average Betweenness Centrality | 10.356 | 20.217 | 1.826 | 0 |

| Median Betweenness Centrality | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Minimum Closeness Centrality | 0.008 | 0.011 | 0.023 | 0.024 |

| Maximum Closeness Centrality | 0.014 | 0.022 | 0.045 | 0.024 |

| Average Closeness Centrality | 0.012 | 0.016 | 0.043 | 0.024 |

| Median Closeness Centrality | 0.013 | 0.016 | 0.043 | 0.024 |

References

- Child, C.D.; Grønbjerg, A.K. Nonprofit Advocacy Organizations: Their Characteristics and Activities. Soc. Sci. Q. 2007, 88, 259–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salamon, L.M.; Geller, L.S. Nonprofit America: A force for democracy? Communiqué 2008, 9, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Pekkanen, R.; Smith, R.S. Nonprofit advocacy in Seattle and Washington, DC. In Nonprofits and Advocacy: Engaging Community and Government in an Era of Retrenchment; Pekkanen, R., Smith, R.S., Tsujinaka, Y., Eds.; Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2014; pp. 47–65. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, G.; Kwak, Y.H. An open government maturity model for social media-based public engagement. Gov. Inf. Q. 2012, 29, 492–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linders, D. From e-government to we-government: Defining a typology for citizen coproduction in the age of social media. Gov. Inf. Q. 2012, 29, 446–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhelm, A.G. Democracy in the Digital Age: Challenges to Political Life in Cyberspace; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Sassi, S. The controversies of the internet and the revitalization of local political life. In Digital Democracy: Issues of Theory and Practice; Hacker, K.L., Van Dijk, J.A.G.M., Eds.; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2000; pp. 90–104. [Google Scholar]

- Keane, J. Structural transformation of the public sphere. In Digital Democracy: Issues of Theory and Practice; Hacker, K.L., Van Dijk, J.A.G.M., Eds.; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2000; pp. 70–89. [Google Scholar]

- Dahlberg, L. The internet and democratic discourse: Exploring the prospects of online deliberative forums extending the public sphere. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2001, 4, 615–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavanaugh, A.L.; Fox, E.A.; Sheetz, S.D.; Yang, S.; Li, L.T.; Shoemaker, D.J.; Natsev, A.; Xie, L. Social media use by government: From the routine to the critical. Gov. Inf. Q. 2012, 29, 480–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, F. What is civil society? In The State of Civil Society in Japan; Schwartz, J.F., Pharr, S.J., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bass, G.D.; Arons, F.D.; Guinane, K.; Carter, F.M. Seen but Not Heard: Strengthen Nonprofit Advocacy; Aspen Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Leech, B. Lobbying and Influence. In The Oxford Handbook of American Political Parties and Interest Groups; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bass, G.D.; Abramson, J.A.; Dewey, E. Effective advocacy: Lessons for nonprofit leaders from research and practice. In Nonprofits and Advocacy: Engaging Community and Government in an Era of Retrenchment; Pekkanen, R., Smith, R.S., Tsujinaka, Y., Eds.; Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2014; pp. 254–293. [Google Scholar]

- Pekkanen, R. Japan’s Dual Civil Society: Members without Advocates; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Leng, R. Japan’s civil society from Kobe to Tohoku: Impact of policy changes on Government-NGO relationship and effectiveness of post-disaster relief. Electron. J. Contemp. Jpn. Stud. 2015, 15. Available online: http://japanesestudies.org.uk/ejcjs/vol15/iss1/leng.html (accessed on 20 September 2016). [Google Scholar]

- Tsujinaka, Y.; Choe, J.; Kubo, Y. Nihon no dantai bunpu to resōsu: Kokka hikaku to kokunai chiiki kan hikaku kara. In Gendai Shakai Shūdan no Seiji Kinō: Rieki Dantai to Shimin Shakai; Tsujinaka, Y., Mori, H., Eds.; Bokutausha: Tokyo, Japan, 2010; pp. 33–64. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Tsujinaka, Y.; Choe, J. Gaikan Shimin shakai no seijika to eikyōryoku. In Gendai Nihon no Shiminshakai Riekidantai; Tsujinaka, Y., Ed.; Bokutakusha: Tokyo, Japan, 2002; pp. 64–83. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Tsujinaka, Y.; Mori, H. Gendai Shakai Shūdan no Seiji Kinō: Rieki Dantai to Shimin Shakai; Bokutausha: Tokyo, Japan, 2010. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Tsujinaka, Y.; Ito, S. Rôkaru Gabanausu: Chihô Seihu to Shimin Shakai; Bokutakusha: Tokyo, Japan, 2010. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto, H. Rieki dantai no eikyōryoku: Takaku teki na shiten kara miru kenryoku kouzou. In Gendai Shakai Shūdan no Seiji Kinō: Rieki Dantai to Shimin Shakai; Tsujinaka, Y., Mori, H., Eds.; Bokutausha: Tokyo, Japan, 2010; pp. 237–252. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Kabashima, I.; Broadbent, J. Referent pluralism: Mass media and politics in Japan. J. Jpn. Stud. 1986, 12, 329–361. [Google Scholar]

- Kabashima, I. Masu media to seiji. Leviathan 1990, 7, 7–29. [Google Scholar]

- Kabashima, I. Sengo Seiji no Kiseki; Iwanami Shoten: Tokyo, Japan, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kabashima, I.; Takeshita, T.; Serikawa, Y. Media to Seiji; Yuhikaku: Tokyo, Japan, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Yamazaki, A. Online campaign and information behavior among Japanese voters: Comparing the 2013 upper house election with the 2012 lower house election. Senkyo kenkyu 2015, 31, 102–113. [Google Scholar]

- Local SNS Study Group (Chiiki SNS kenkyūkai) “Facebook Pages Run by Japanese Local Governments”. Available online: http://www.local-socio.net/2013/02/facebook_3.html (accessed on 20 September 2016).

- Kaigo, M.; Okura, S. Exploring functions in citizen engagement on a local government Facebook page in Japan. Telemat. Inform. 2016, 33, 584–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgatti, S. Centrality and Network Flow. Soc. Netw. 2005, 27, 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.A.; Shneiderman, B.; Milic-Frayling, N.; Rodrigues, M.E.; Barash, V.; Dunne, C.; Capone, T.; Perer, A.; Gleave, E. Analyzing (social media) networks with NodeXL. In Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference on Communities and Technologies, University Park, PA, USA, 25–27 June 2009.

- Hansen, D.; Shneiderman, B.; Smith, A.M. Analyzing Social Media Networks with NodeXL: Insights from a Connected World; Morgan Kaufmann Publishers: Burlington, VT, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

| The Center (Leading Actors) | The Periphery | |

|---|---|---|

| NHA network | NHA Civil servants in Tsukuba Users of the Tsukuba Civic Activities Cyber-Square | Users of the Tsukuba Civic Activities Cyber-Square |

| Disaster network | Welfare groups Civil servants in Tsukuba Users of the Tsukuba Civic Activities Cyber-Square | Academic/educational groups Users of the Tsukuba Civic Activities Cyber-Square |

| Welfare network | Tsukuba Civic Activities Cyber-Square Welfare groups | Welfare groups Users of the Tsukuba Civic Activities Cyber-Square |

| Volunteering network | None | None |

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Okura, S.; Kaigo, M. Who Leads Advocacy through Social Media in Japan? Evidence from the “Tsukuba Civic Activities Cyber-Square” Facebook Page. Information 2016, 7, 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/info7040066

Okura S, Kaigo M. Who Leads Advocacy through Social Media in Japan? Evidence from the “Tsukuba Civic Activities Cyber-Square” Facebook Page. Information. 2016; 7(4):66. https://doi.org/10.3390/info7040066

Chicago/Turabian StyleOkura, Sae, and Muneo Kaigo. 2016. "Who Leads Advocacy through Social Media in Japan? Evidence from the “Tsukuba Civic Activities Cyber-Square” Facebook Page" Information 7, no. 4: 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/info7040066