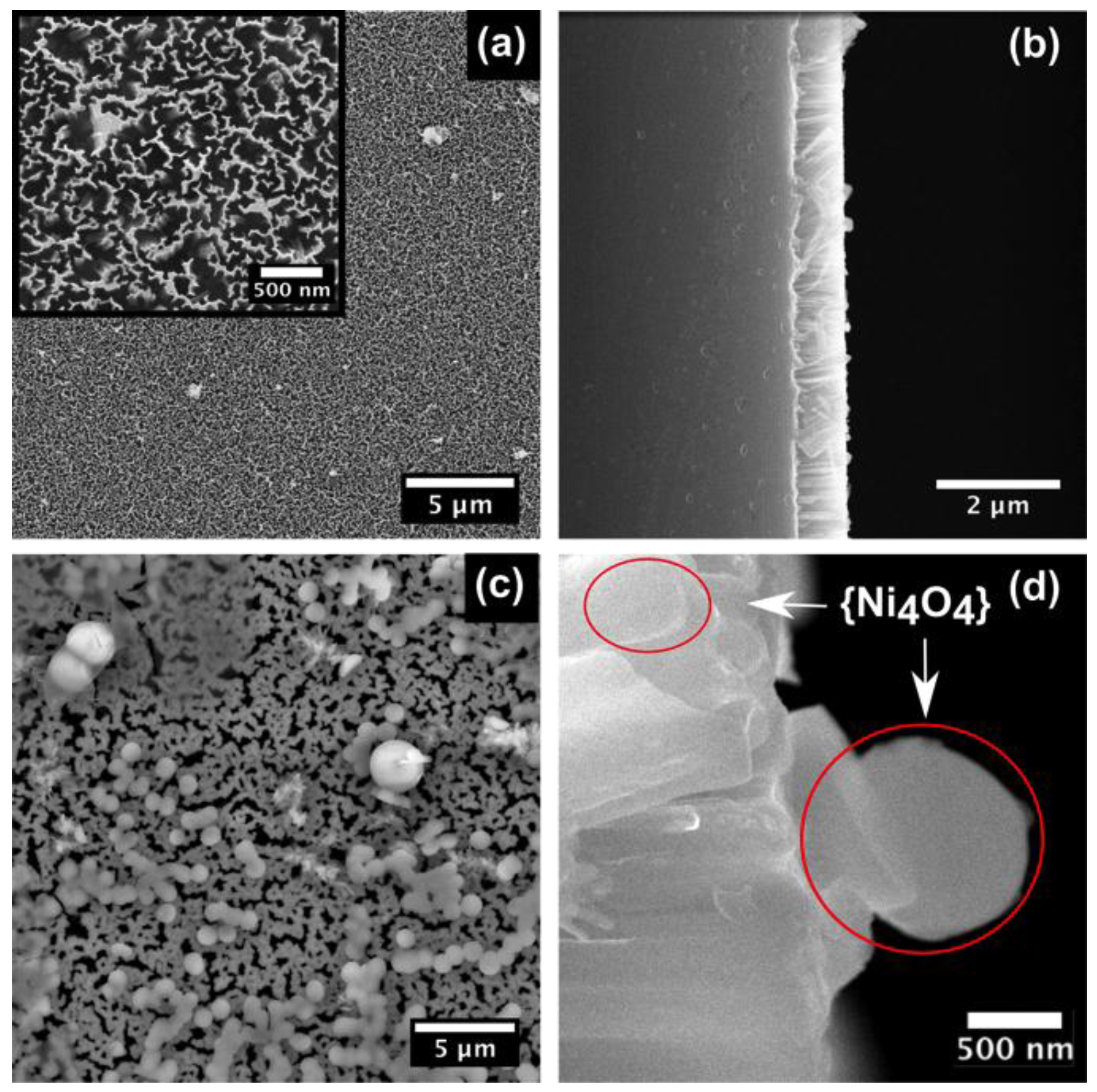

{Ni4O4} Cluster Complex to Enhance the Reductive Photocurrent Response on Silicon Nanowire Photocathodes

Abstract

:1. Introduction

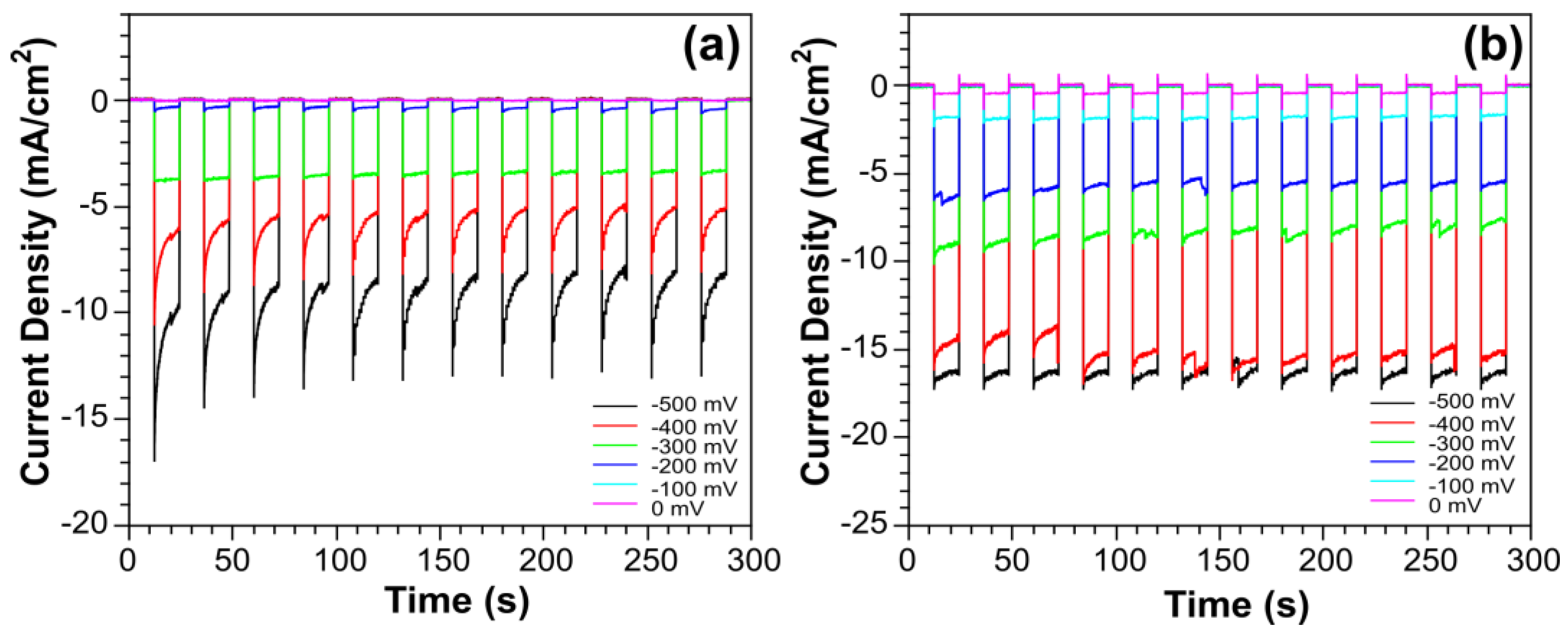

2. Results and Discussion

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Synthesis of {Ni4O4} Clusters

3.2. Fabrication of SiNWs

3.3. Electrode Fabrication

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fujishima, A.; Honda, K. Electrochemical Photolysis of Water at a Semiconductor Electrode. Nature 1972, 238, 37–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Contestabile, M.; Offer, G.J.; Slade, R.; Jaeger, F.; Thoennes, M. Battery electric vehicles, hydrogen fuel cells and biofuels. Which will be the winner? Energy Environ. Sci. 2011, 4, 3754–3772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balzani, V.; Moggi, L.; Manfrin, M.F.; Bolletta, F.; Gleria, M. Solar Energy Conversion by Water Photodissociation Transition metal complexes can provide low-energy cyclic systems for catalytic photodissociation of water. Science 1975, 189, 852–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolton, J.R.; Strickler, S.J.; Connolly, J.S. Limiting and realizable efficiencies of solar photolysis of water. Nature 1985, 316, 495–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tachibana, Y.; Vayssieres, L.; Durrant, J.R. Artificial photosynthesis for solar water-splitting. Nat. Photonics 2012, 6, 511–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawasaki, S.; Takahashi, R.; Yamamoto, T.; Kobayashi, M.; Kumigashira, H.; Yoshinobu, J.; Komori, F.; Kudo, A.; Lippmaa, M. Photoelectrochemical water splitting enhanced by self-assembled metal nanopillars embedded in an oxide semiconductor photoelectrode. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 11818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarnowska, M.; Bienkowski, K.; Barczuk, P.J.; Solarska, R.; Augustynski, J. Highly Efficient and Stable Solar Water Splitting at (Na)WO3 Photoanodes in Acidic Electrolyte Assisted by Non-Noble Metal Oxygen Evolution Catalyst. Adv. Energy Mater. 2016, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touge, T.; Nara, H.; Fujiwhara, M.; Kayaki, Y.; Ikariya, T. Efficient Access to Chiral Benzhydrols via Asymmetric Transfer Hydrogenation of Unsymmetrical Benzophenones with Bifunctional Oxo-Tethered Ruthenium Catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 10084–10087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.; Terashima, H.; Shimodaira, Y.; Teramura, K.; Hara, M.; Kobayashi, H.; Domen, K.; Yashima, M. Zinc Germanium Oxynitride as a Photocatalyst for Overall Water Splitting under Visible Light. J. Phys. Chem. C 2007, 111, 1042–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, R.; Shinmei, K.; Hara, K.; Ohtani, B. Robust dye-sensitized overall water splitting system with two-step photoexcitation of coumarin dyes and metal oxide semiconductors. Chem. Commun. 2009, 3577–3579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, L.; McDaniel, M.D.; Wang, S.; Posadas, A.B.; Li, X.; Huang, H.; Lee, J.C.; Demkov, A.A.; Bard, A.J.; Ekerdt, J.G.; et al. A silicon-based photocathode for water reduction with an epitaxial SrTiO3 protection layer and a nanostructured catalyst. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2015, 10, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, J.; Steier, L.; Son, M.-K.; Schreier, M.; Mayer, M.T.; Gratzel, M. Cu2O Nanowire Photocathodes for Efficient and Durable Solar Water Splitting. Nano Lett. 2016, 16, 1848–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masudy-Panah, S.; Moakhar, R.S.; Chua, C.S.; Kushwaha, A.; Wong, T.I.; Dalapati, G.K. Rapid thermal annealing assisted stability and efficiency enhancement in a sputter deposited CuO photocathode. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 29383–29390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masudy-Panah, S.; Siavash Moakhar, R.; Chua, C.S.; Tan, H.R.; Wong, T.I.; Chi, D.; Dalapati, G.K. Nanocrystal Engineering of Sputter-Grown CuO Photocathode for Visible-Light-Driven Electrochemical Water Splitting. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 1206–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, J.; Yan, Y.; Young, J.L.; Steirer, K.X.; Neale, N.R.; Turner, J.A. Water reduction by a p-GaInP2 photoelectrode stabilized by an amorphous TiO2 coating and a molecular cobalt catalyst. Nat. Mater. 2016, 15, 456–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, S.U.M.; Al-Shahry, M.; Ingler, W.B. Efficient Photochemical Water Splitting by a Chemically Modified n-TiO2. Science 2002, 297, 2243–2245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macdonald, T.J.; Mange, Y.J.; Dewi, M.R.; Islam, H.U.; Parkin, I.P.; Skinner, W.M.; Nann, T. CuInS2/ZnS nanocrystals as sensitisers for NiO photocathodes. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 13324–13331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekaran, S.; Macdonald, T.J.; Mange, Y.J.; Voelcker, N.H.; Nann, T. A quantum dot sensitized catalytic porous silicon photocathode. J. Mater. Chem. A 2014, 2, 9478–9481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdonald, T.J.; Tune, D.D.; Dewi, M.R.; Bear, J.C.; McNaughter, P.D.; Mayes, A.G.; Skinner, W.M.; Parkin, I.P.; Shapter, J.G.; Nann, T. SWCNT photocathodes sensitised with InP/ZnS core–shell nanocrystals. J. Mater. Chem. C 2016, 4, 3379–3384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekaran, S.; McInnes, S.J.P.; Macdonald, T.J.; Nann, T.; Voelcker, N.H. Porous silicon nanoparticles as a nanophotocathode for photoelectrochemical water splitting. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 85978–85982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekaran, S.; Nann, T.; Voelcker, N.H. Nanostructured silicon photoelectrodes for solar water electrolysis. Nano Energy 2015, 17, 308–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Kulkarni, J.S.; Collins, G.; Petkov, N.; Almecija, D.; Boland, J.J.; Erts, D.; Holmes, J.D. Synthesis and Electrical and Mechanical Properties of Silicon and Germanium Nanowires. Chem. Mater. 2008, 20, 5954–5967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Li, L.; Gao, Y.; Wang, C.; Jiang, J.; Xiong, Y. The Nature of Photocatalytic “Water Splitting” on Silicon Nanowires. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 2980–2985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, Y.; Abrams, B.L.; Vesborg, P.C.K.; Bjorketun, M.E.; Herbst, K.; Bech, L.; Setti, A.M.; Damsgaard, C.D.; Pedersen, T.; Hansen, O.; et al. Bioinspired molecular co-catalysts bonded to a silicon photocathode for solar hydrogen evolution. Nat. Mater. 2011, 10, 434–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Macdonald, T.J.; Tune, D.D.; Dewi, M.R.; Gibson, C.T.; Shapter, J.G.; Nann, T. A TiO2 Nanofiber–Carbon Nanotube-Composite Photoanode for Improved Efficiency in Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells. ChemSusChem 2015, 8, 3396–3400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, D.P.; Macdonald, T.J.; Wolfrum, B.; Stockmann, R.; Nann, T.; Offenhausser, A.; Thierry, B. Photoresponsive properties of ultrathin silicon nanowires. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2014, 105, 231116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mor, G.K.; Shankar, K.; Paulose, M.; Varghese, O.K.; Grimes, C.A. Enhanced Photocleavage of Water Using Titania Nanotube Arrays. Nano Lett. 2005, 5, 191–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nann, T.; Ibrahim, S.K.; Woi, P.-M.; Xu, S.; Ziegler, J.; Pickett, C.J. Water Splitting by Visible Light: A Nanophotocathode for Hydrogen Production. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 1574–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.-Y.; Chen, W.-Q.; Hu, B.; Chen, Y.-M.; Li, W.; Li, Y. A unique tetranuclear cubane-like {Ni4O4} complex supported by hydroxyl-rich ligands: Synthesis, crystal structure and magnetic property. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2012, 16, 74–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baktash, E.; Littlewood, P.; Pfrommer, J.; Schomacker, R.; Driess, M.; Thomas, A. Controlled Formation of Nickel Oxide Nanoparticles on Mesoporous Silica using Molecular {Ni4O4} Clusters as Precursors: Enhanced Catalytic Performance for Dry Reforming of Methane. ChemCatChem 2015, 7, 1280–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekaran, S.; Macdonald, T.J.; Gerson, A.R.; Nann, T.; Voelcker, N.H. Boron-Doped Silicon Diatom Frustules as a Photocathode for Water Splitting. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 17381–17387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, X.-B.; Li, Y.-G.; Zhang, Z.-M.; Tan, H.-Q.; Lu, Y.; Wang, E.-B. Polyoxometalate-Based Nickel Clusters as Visible Light-Driven Water Oxidation Catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 5486–5493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mange, Y.J.; Chandrasekaran, S.; Hollingsworth, N.; Voelcker, N.H.; Parkin, I.P.; Nann, T.; Macdonald, T.J. {Ni4O4} Cluster Complex to Enhance the Reductive Photocurrent Response on Silicon Nanowire Photocathodes. Nanomaterials 2017, 7, 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano7020033

Mange YJ, Chandrasekaran S, Hollingsworth N, Voelcker NH, Parkin IP, Nann T, Macdonald TJ. {Ni4O4} Cluster Complex to Enhance the Reductive Photocurrent Response on Silicon Nanowire Photocathodes. Nanomaterials. 2017; 7(2):33. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano7020033

Chicago/Turabian StyleMange, Yatin J., Soundarrajan Chandrasekaran, Nathan Hollingsworth, Nicolas H. Voelcker, Ivan P. Parkin, Thomas Nann, and Thomas J. Macdonald. 2017. "{Ni4O4} Cluster Complex to Enhance the Reductive Photocurrent Response on Silicon Nanowire Photocathodes" Nanomaterials 7, no. 2: 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano7020033