Three-Dimensional BiOI/BiOX (X = Cl or Br) Nanohybrids for Enhanced Visible-Light Photocatalytic Activity

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Experimental

2.1. Materials

2.2. Synthesis of BiOX (X = Cl, Br, I)

2.3. Synthesis of BiOI/BiOX (X = Cl, Br)

2.4. Characterization Techniques

2.5. Evaluation of the Photocatalysts

3. Results and Discussion

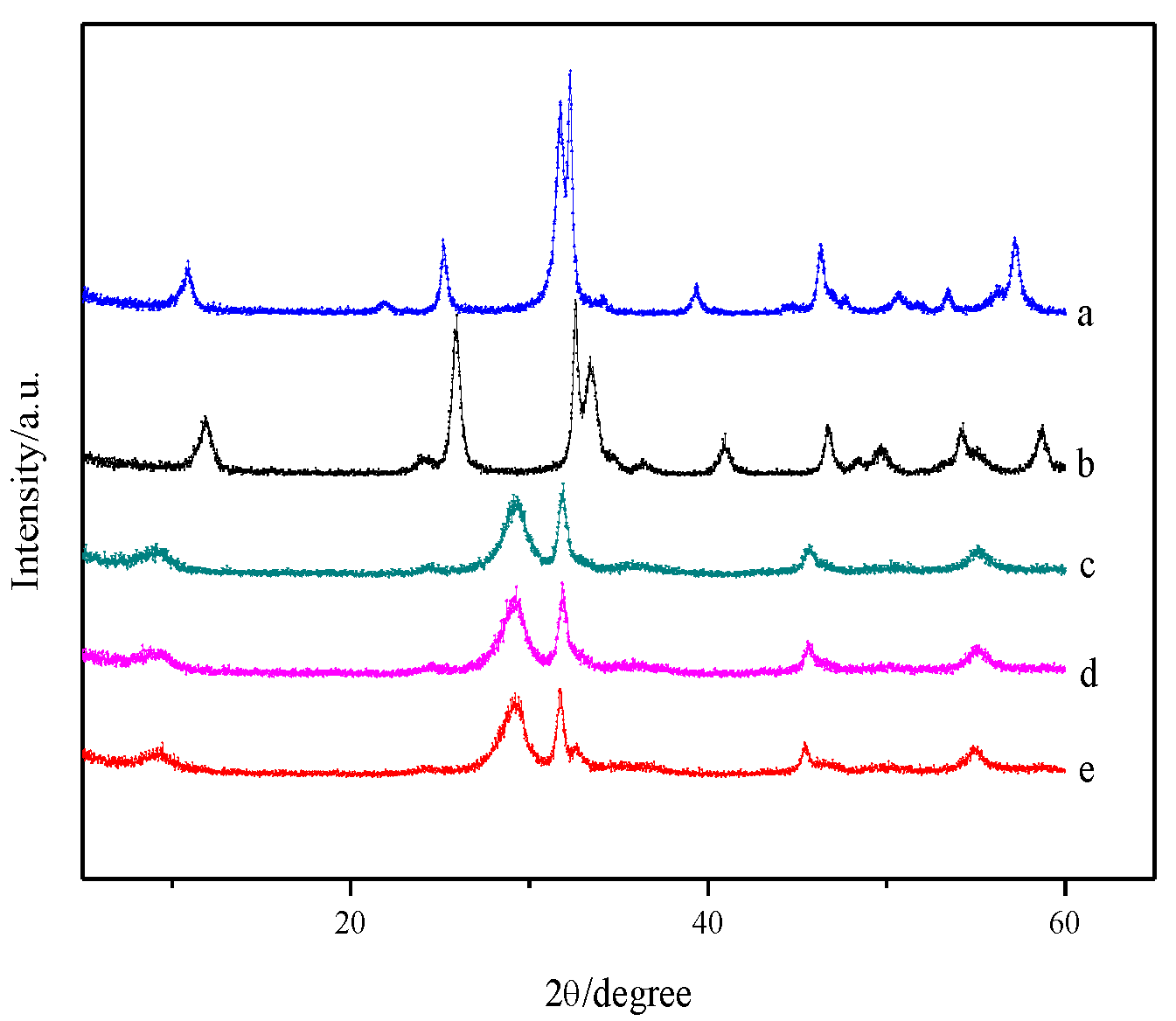

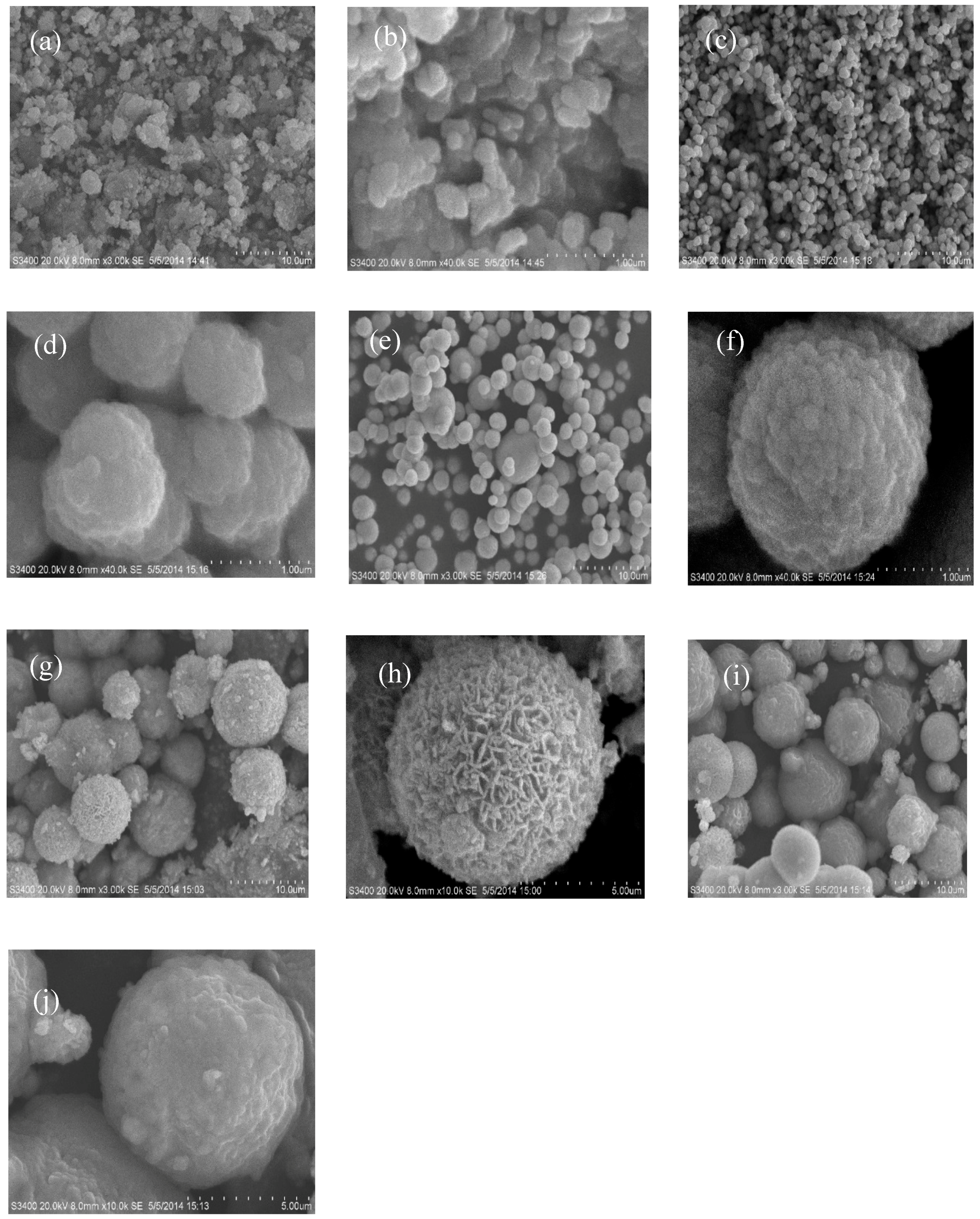

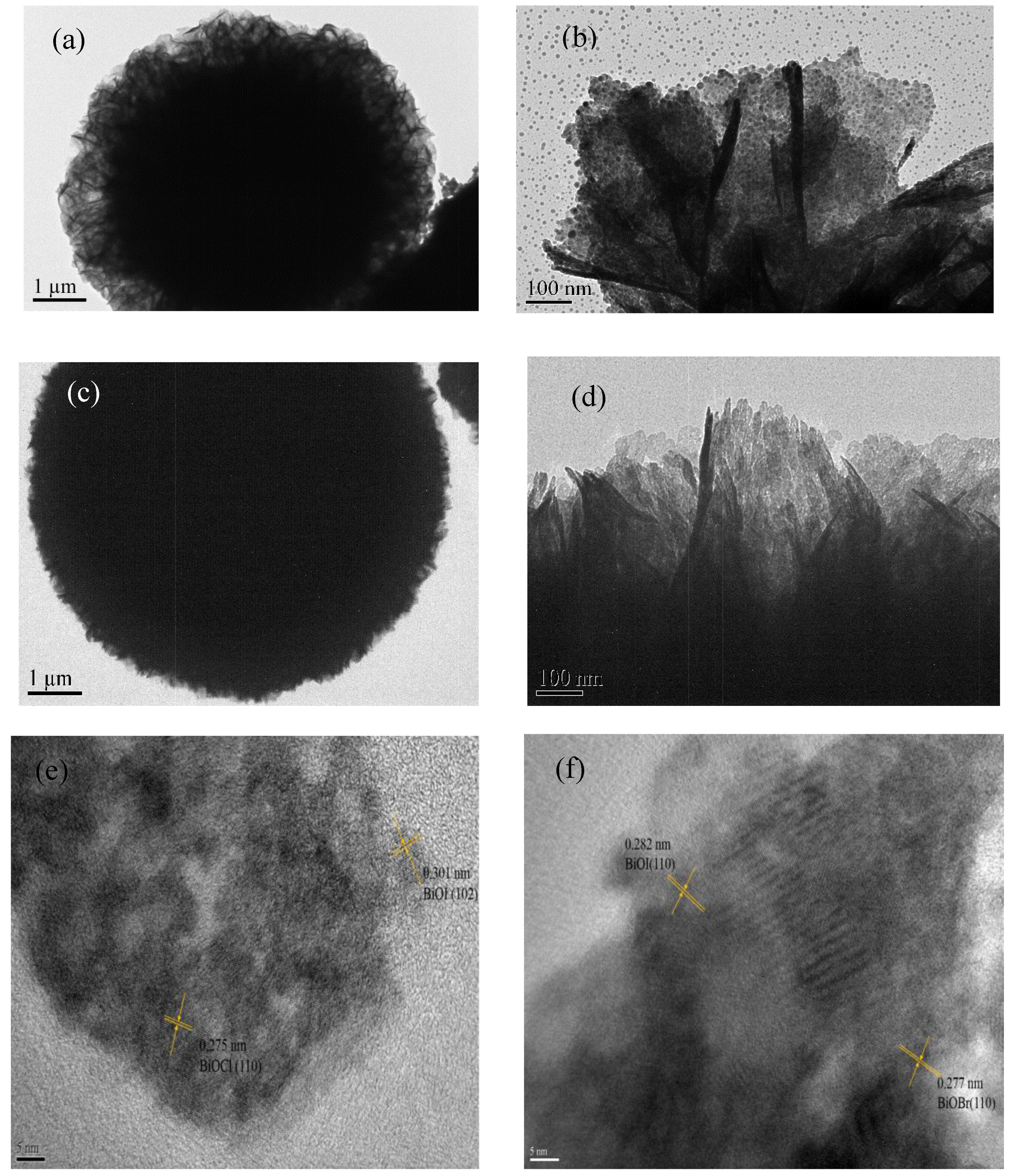

3.1. Morphology and Structure

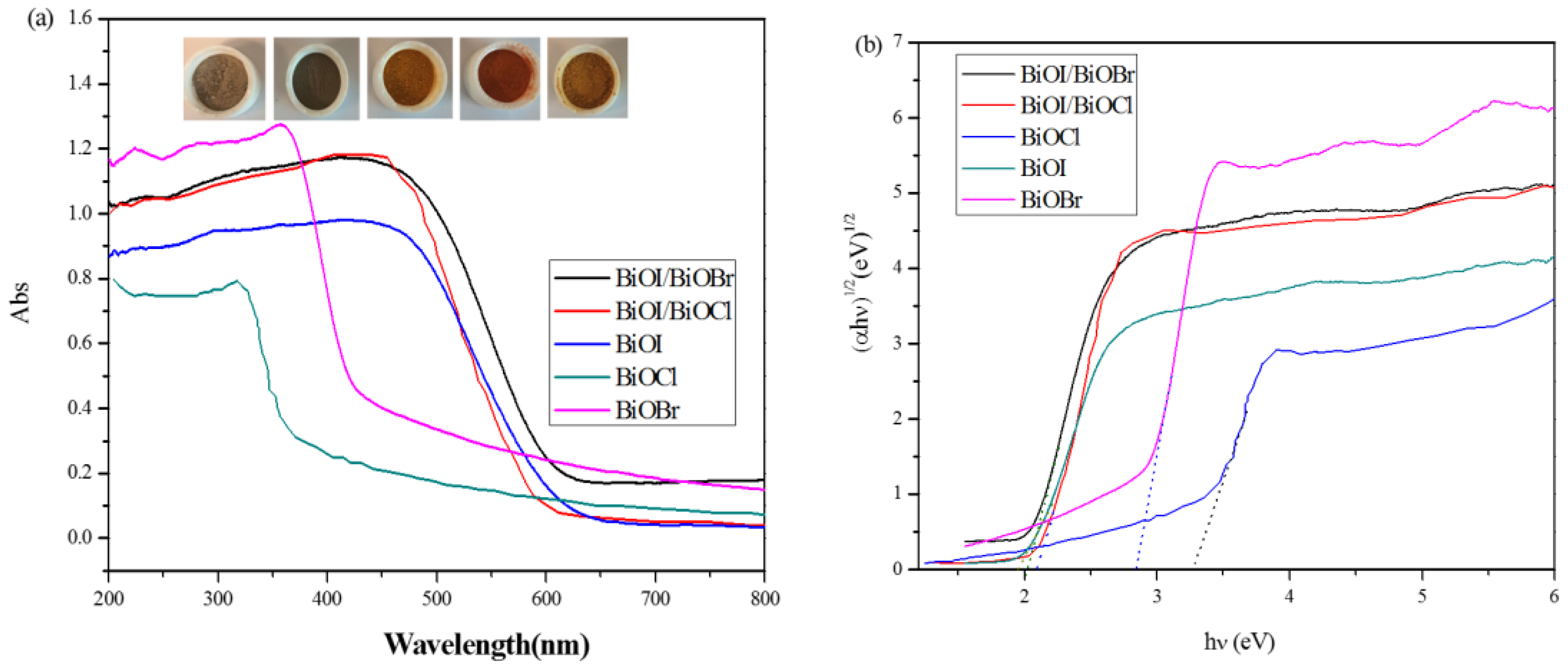

3.2. Optical Properties

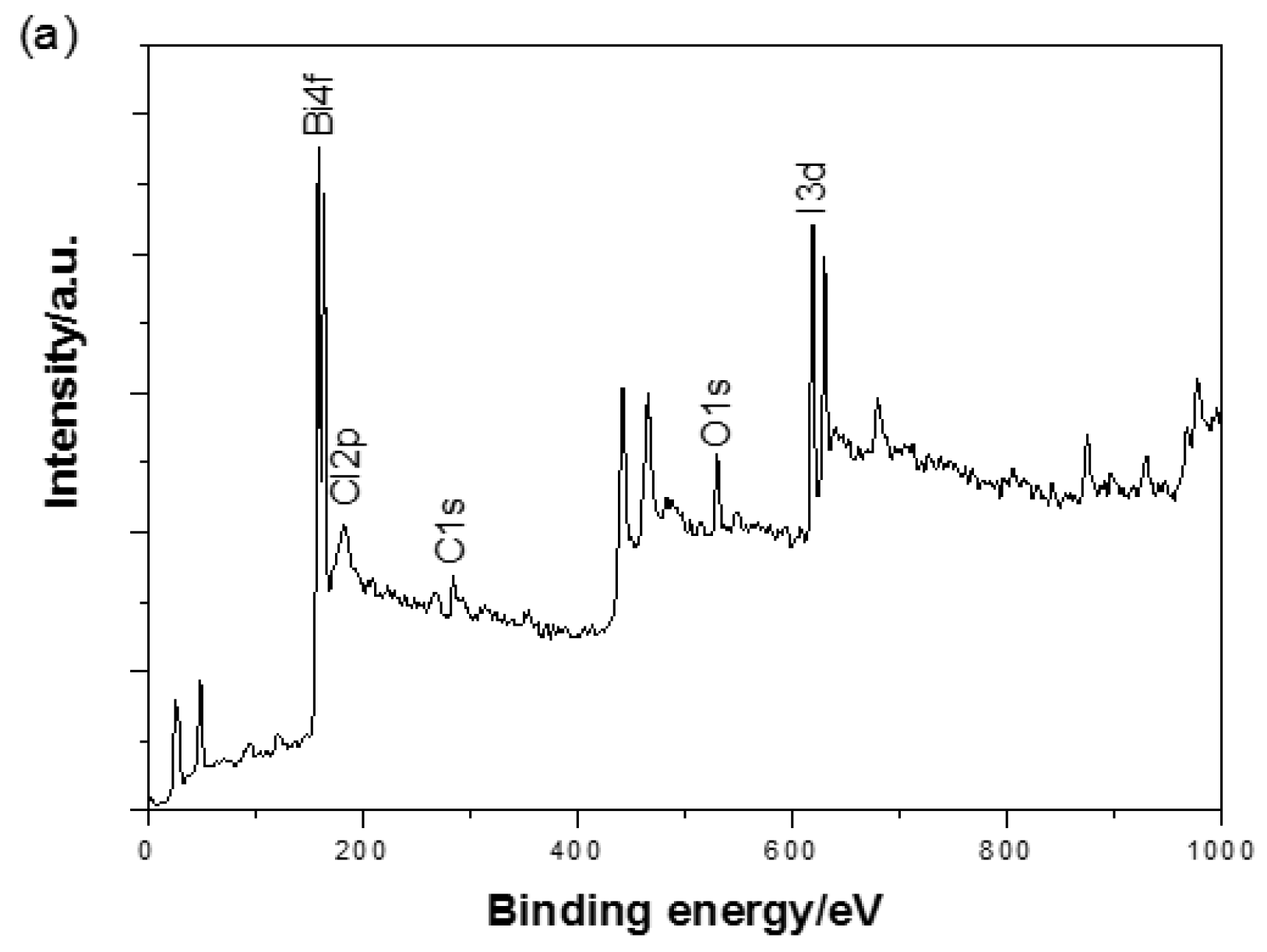

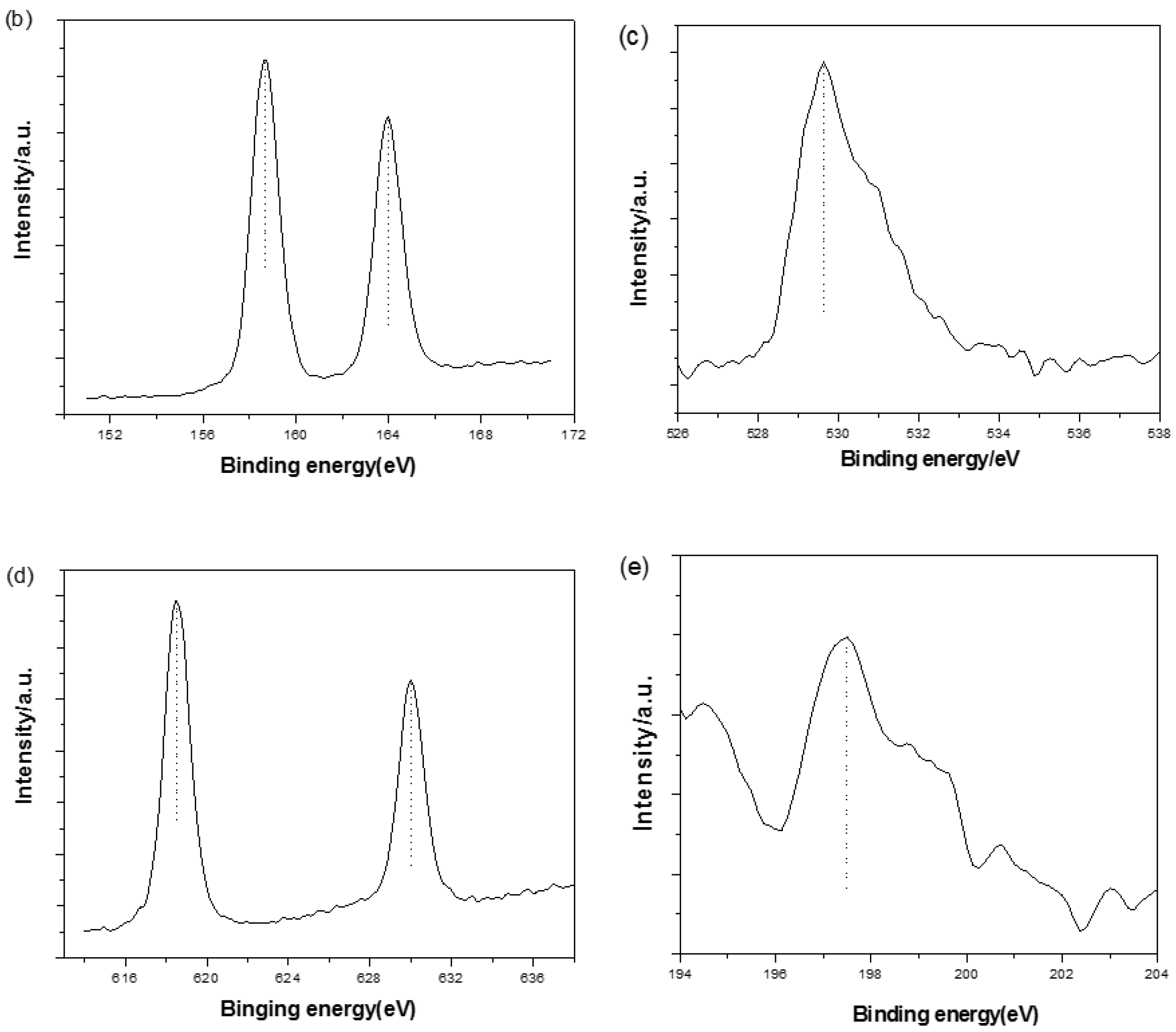

3.3. XPS Analysis

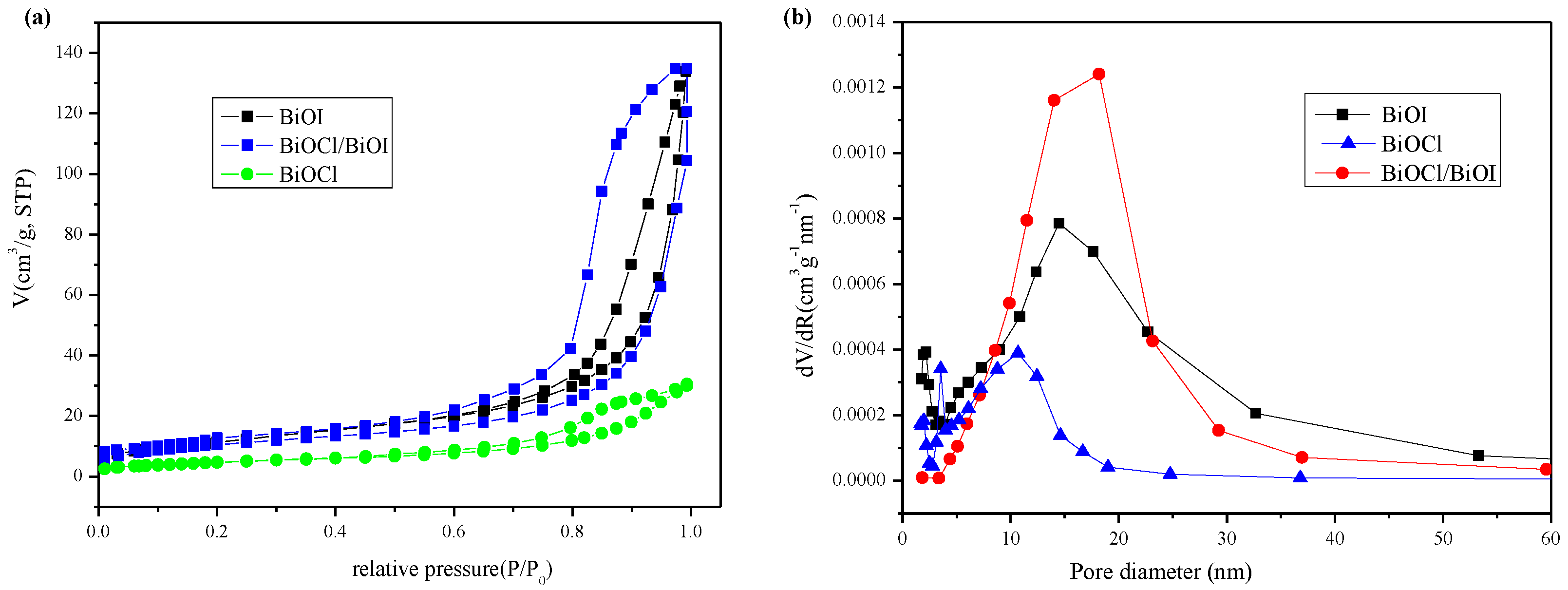

3.4. Specific Surface Areas and Pore Structure

3.5. Photocatalytic Degradation of MO

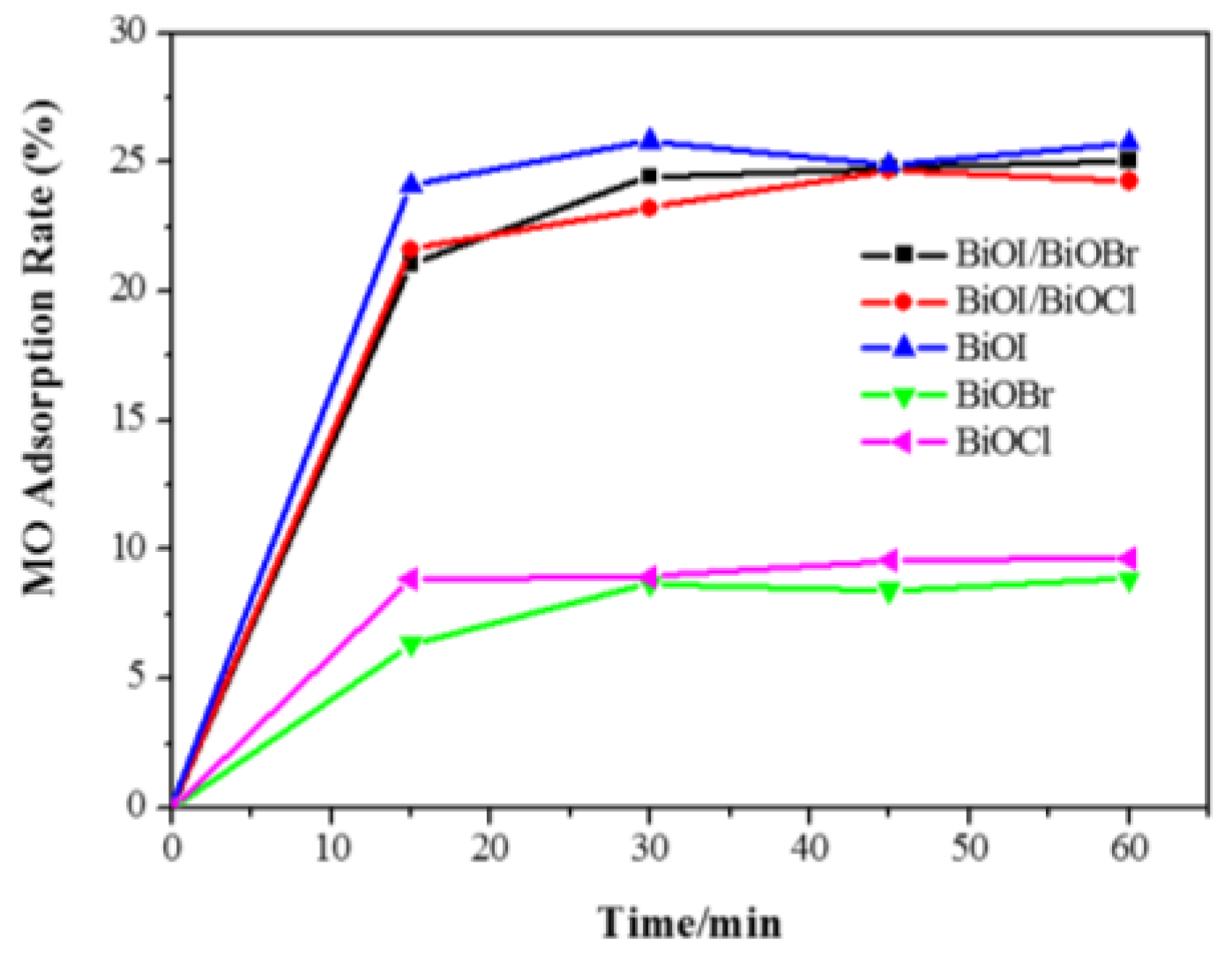

3.5.1. Adsorption of MO

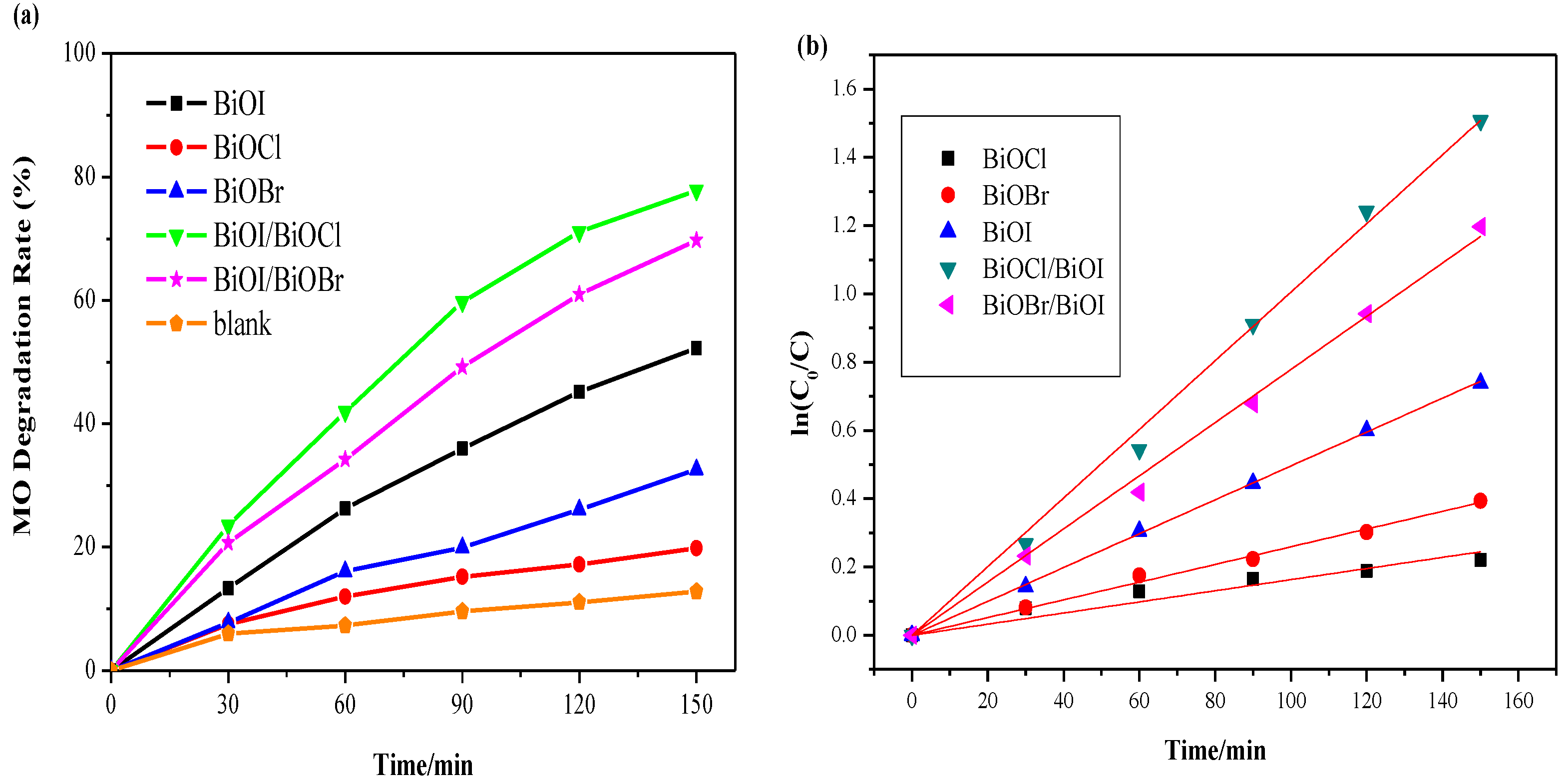

3.5.2. Comparison of Photocatalytic Activity

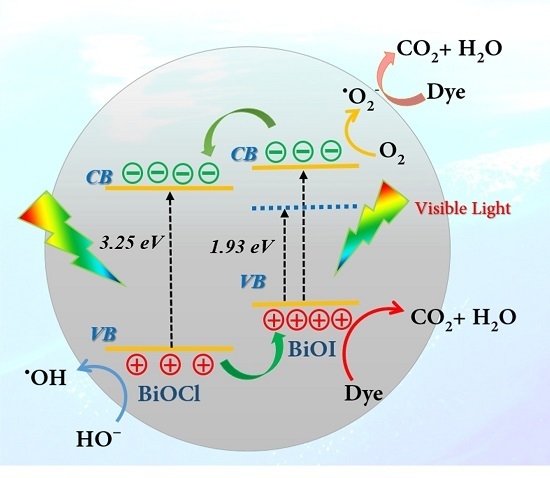

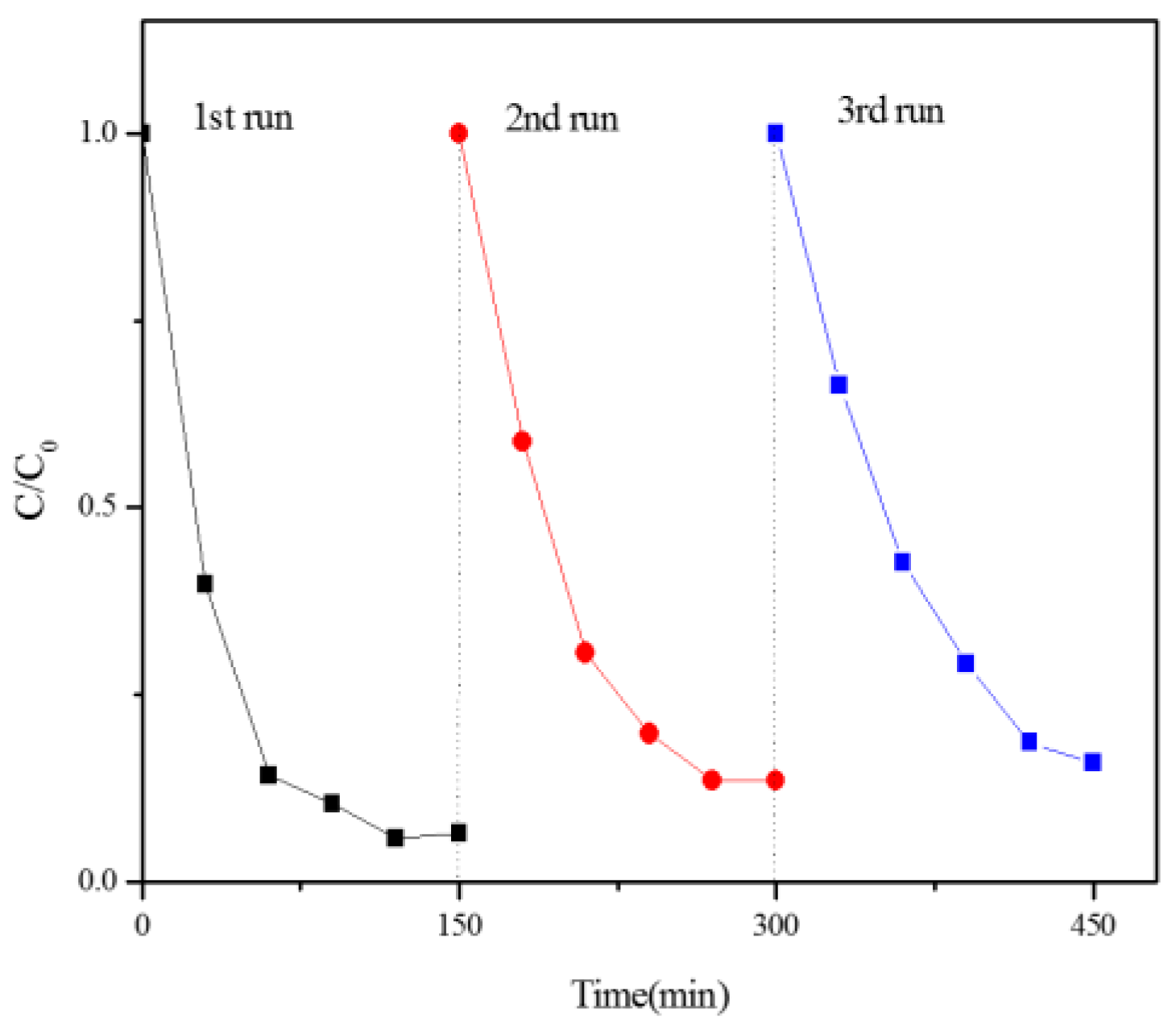

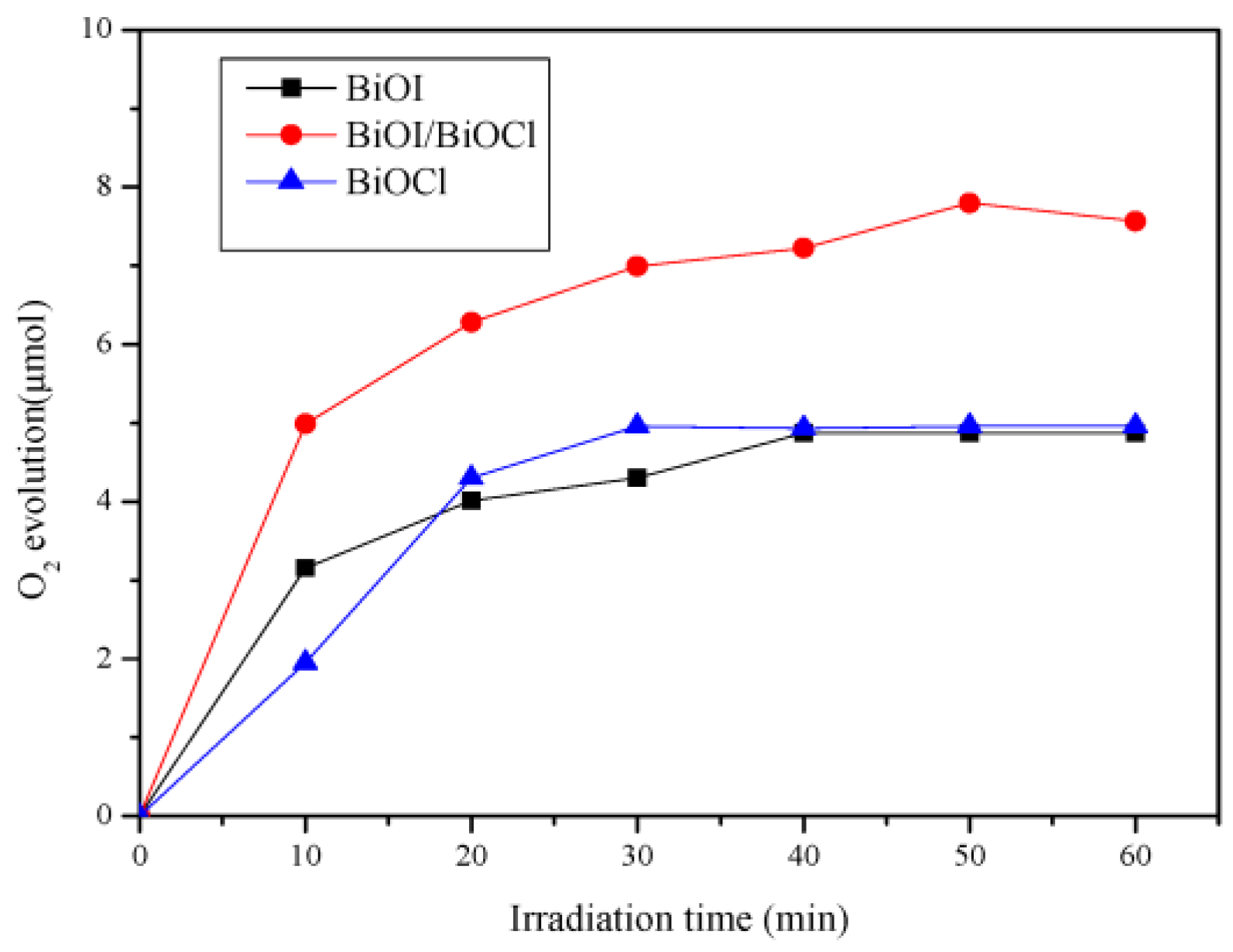

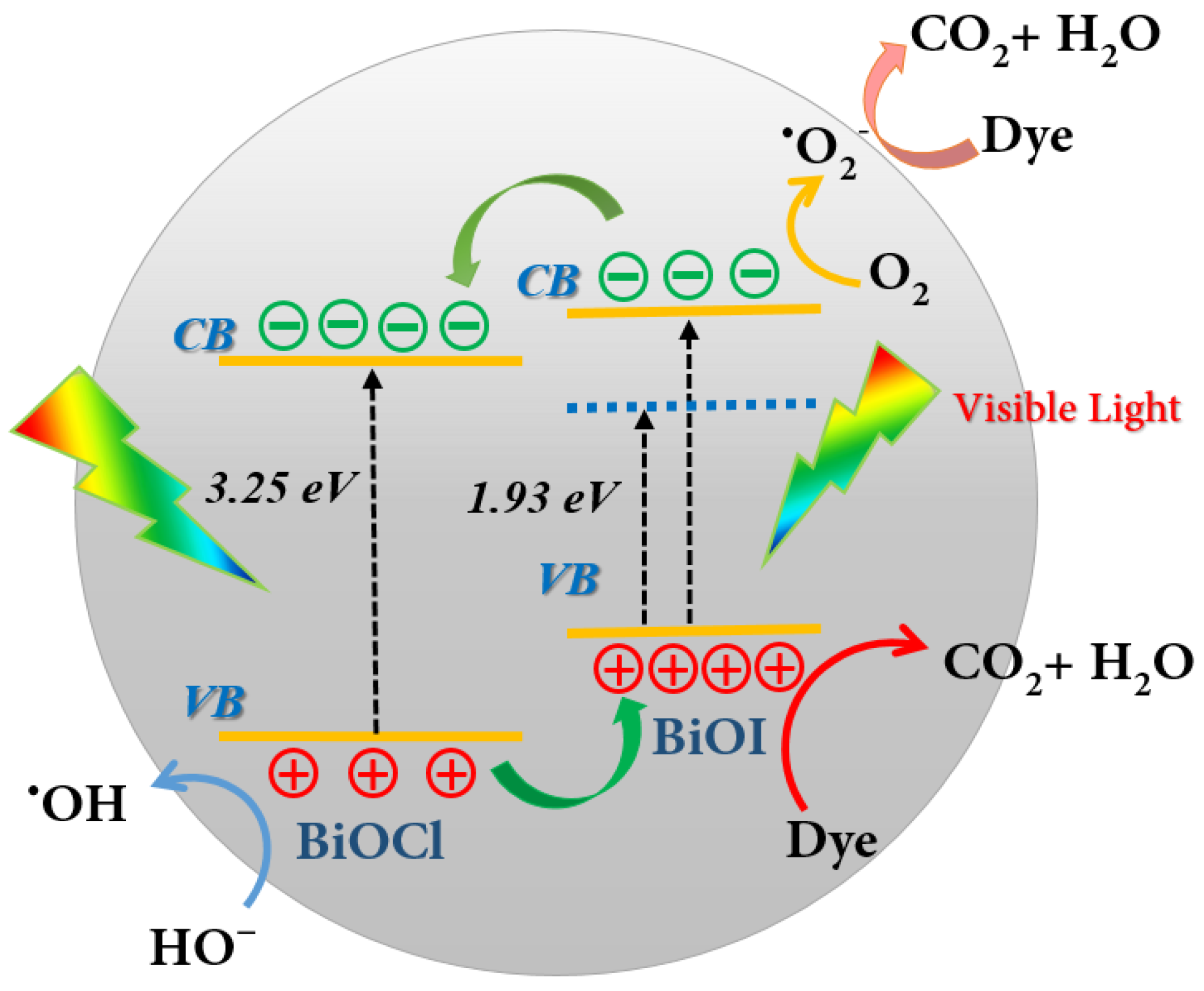

3.5.3. Photocatalytic Mechanism of the BiOI/BiOCl Composite

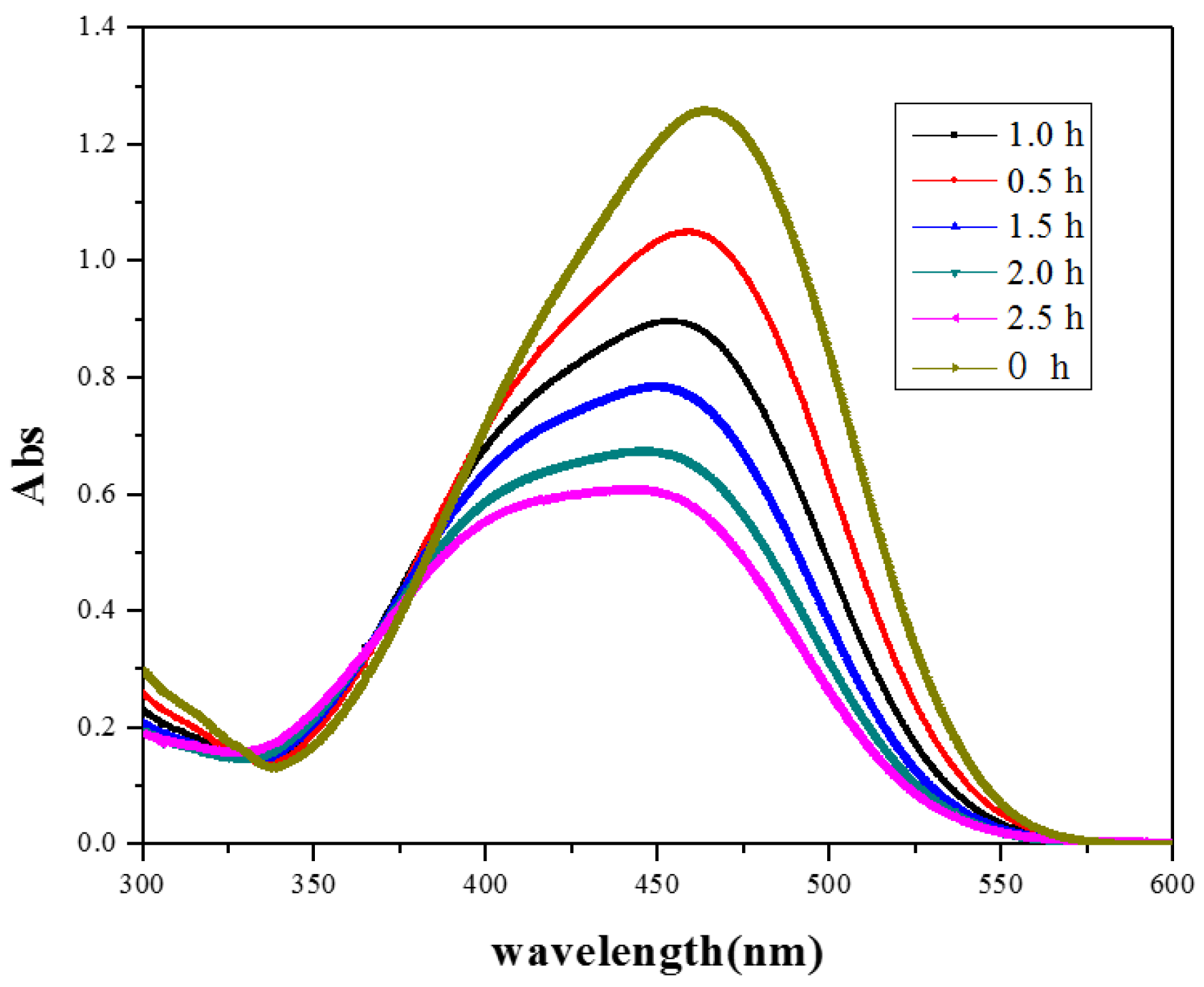

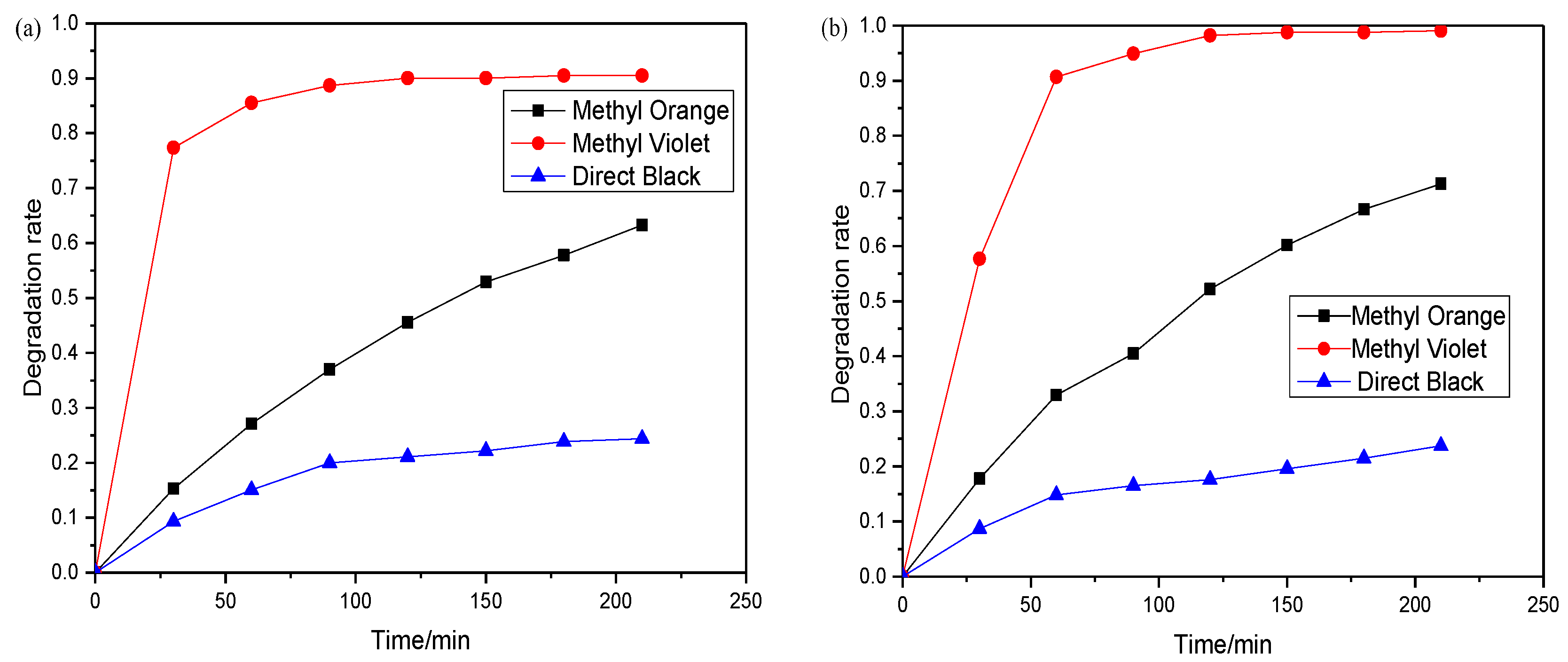

3.5.4. Photodegradation of Dyes under Natural Solar Light Irradiation

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Dye | Molecular Structure | Application | Safety |

|---|---|---|---|

| Methyl Orange |  | pH indicator | mutagenicproperties |

| Methyl Violet |  | purple dye for textiles | mutagen and mitotic poison |

| Direct Black |  | silk dyeing/printing/leather shading | carcinogenicity andreproductive toxicity |

References

- Zhang, Z.; Shao, C.; Li, X.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, M.; Mu, J.; Zhang, P.; Guo, Z.; Liu, Y. Hierarchical assembly of ultrathin hexagonal SnS2 nanosheets onto electrospun TiO2 nanofibers: Enhanced photocatalytic activity based on photoinduced interfacial charge transfer. Nanoscale 2013, 5, 606–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatkhande, D.S.; Pangarkar, V.G.; Beenackers, A.A. Photocatalytic degradation for environmental applications—A review. J. Chem. Technol. Biot. 2002, 77, 102–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, J.; Sun, H.Q.; Zhang, H.Y.; Duan, X.G.; Liang, P.; Li, X.Y.; Tade, M.; Liu, S.M.; Wang, S.B. Facile assembly of Bi2O3/Bi2S3/MoS2 n-p heterojunction with layered n-Bi2O3 and p-MoS2 for enhanced photocatalytic water oxidation and pollutant degradation. Appl. Catal. B 2017, 200, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.B.; Zhang, H.M.; Liu, P.R.; Wang, D.; Li, Y.; Zhao, H.J. Cross-linked g-C3N4/rGO nanocomposites with tunable band structure and enhanced visible light photocatalytic activity. Small 2013, 9, 3336–3344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Surendar, T.; Baruah, A.; Shanker, V. Synthesis of a novel and stable g-C3N4–Ag3PO4 hybrid nanocomposite photocatalyst and study of the photocatalytic activity under visible light irradiation. J. Mater. Chem. A 2013, 1, 5333–5340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, Y.S.; Lee, E.Z.; Wang, X.; Hong, W.H.; Stucky, G.D.; Thomas, A. From melamine-cyanuric acid supramolecular aggregates to carbon nitride hollow spheres. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2013, 23, 3661–3667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Lu, G.Q.M.; Wang, L. Shell-in-shell TiO2 hollow spheres synthesized by one-pot hydrothermal method for dye-sensitized solar cell application. Energ Environ. Sci. 2011, 4, 3565–3572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Wen, Z.; Cui, S.; Guo, X.; Chen, J. Constructing 2d porous graphitic C3N4 nanosheets/nitrogen-doped graphene/layered MoS2 ternary nanojunction with enhanced photoelectrochemical activity. Adv. Mater. 2013, 25, 6291–6297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Luo, W.; Cao, D.; Zhao, X.; Li, Z.; Yu, T.; Zou, Z. A co-catalyst-loaded Ta3N5 photoanode with a high solar photocurrent for water splitting upon facile removal of the surface layer. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 11016–11020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Takata, T.; Cha, D.; Takanabe, K.; Minegishi, T.; Kubota, J.; Domen, K. Vertically aligned Ta3N5 nanorod arrays for solar-driven photoelectrochemical water splitting. Adv. Mater. 2013, 25, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Guo, F.; Wang, X. An optimized and general synthetic strategy for fabrication of polymeric carbon nitride nanoarchitectures. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2013, 23, 3008–3014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- In, S.I.; Vaughn, D.D.; Schaak, R.E. Hybrid CuO-TiO2−xNx hollow nanocubes for photocatalytic conversion of CO2 into methane under solar irradiation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 3915–3918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, J.; Peng, T.; Zhang, X.; Li, K.; Ye, L.; Zan, L. Effect of graphitic carbon nitride microstructures on the activity and selectivity of photocatalytic CO2 reduction under visible light. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2013, 3, 1253–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Mao, S.S. Titanium dioxide nanomaterials: Synthesis, properties, modifications, and applications. Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 2891–2959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Schultz, A.M.; Li, L.; Chien, H.; Salvador, P.A.; Rohrer, G.S. Combinatorial substrate epitaxy: A high-throughput method for determining phase and orientation relationships and its application to BiFeO3/TiO2 heterostructures. Acta Mater. 2012, 60, 6486–6493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Liu, Y.; Wei, Z.; Yang, S.; He, H.; Sun, C. Fabrication of a novel p–n heterojunction photocatalyst n-BiVO4@p-MoS2 with core–shell structure and its excellent visible-light photocatalytic reduction and oxidation activities. Appl. Catal. B 2016, 185, 242–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, J.; Duan, X.G.; Luo, S.; Zhang, H.Y.; Sun, H.Q.; Liu, J.; Tade, M.; Wang, S.B. UV-assisted construction of 3D hierarchical rGO/Bi2MoO6 composites for enhanced photocatalytic water oxidation. Chem. Eng. J. 2017, 313, 1447–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.-Q.; Chang, N.; Han, D.-Q.; Zhou, A.-Q.; Xu, X.-H. The enhanced visible light photocatalytic activity of nanosheet-like Bi2WO6 obtained by acid treatment for the degradation of rhodamine B. Mater. Lett. 2010, 64, 2135–2137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y.; Wang, G.; Song, S.; Fan, W.; Zhang, H. Synthesis, characterization and assembly of BiOCl nanostructure and their photocatalytic properties. CrystEngComm 2009, 11, 1857–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, L.; Zan, L.; Tian, L.; Peng, T.; Zhang, J. The {001} facets-dependent high photoactivity of BiOCl nanosheets. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 6951–6953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwase, A.; Kudo, A. Photoelectrochemical water splitting using visible-light-responsive BiVO4 fine particles prepared in an aqueous acetic acid solution. J. Mater. Chem. 2010, 20, 7536–7542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Huang, B.; Wang, Z.; Qin, X.; Zhang, X.; Dai, Y. One-pot miniemulsion-mediated route to BiOBr hollow microspheres with highly efficient photocatalytic activity. Chem. Eur. J. 2011, 17, 8039–8043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soler-Illia, G.J.D.A.; Sanchez, C.; Lebeau, B.; Patarin, J. Chemical strategies to design textured materials: From microporous and mesoporous oxides to nanonetworks and hierarchical structures. Chem. Rev. 2002, 102, 4093–4138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, Z.; Wang, F.; Xin, F.; Zhang, B. Simple solvothermal routes to synthesize 3d BiOBrxI1−x microspheres and their visible-light-induced photocatalytic properties. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2011, 50, 6688–6694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, F.; Sun, Y.; Fu, M.; Wu, Z.; Lee, S.C. Room temperature synthesis and highly enhanced visible light photocatalytic activity of porous BiOI/BiOCl composites nanoplates microflowers. J. Hazard. Mater. 2012, 219–220, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, X.; Hao, R.; Liang, M.; Zuo, X.; Nan, J.; Li, L.; Zhang, W. One-pot solvothermal synthesis of three-dimensional (3d) BiOI/BiOCl composites with enhanced visible-light photocatalytic activities for the degradation of bisphenol-a. J. Hazard. Mater. 2012, 233–234, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.; Li, F.; Zhang, M.; Li, T.; Cao, W. Preparation and first-principles study for electronic structures of BiOI/BiOCl composites with highly improved photocatalytic and adsorption performances. J. Mol. Catal. A 2016, 423, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Lu, G.; Wang, Y.; Guo, Y.; Guo, Y. A high activity photocatalyst of hierarchical 3d flowerlike ZnO microspheres: Synthesis, characterization and catalytic activity. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2012, 377, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Ai, Z.; Jia, F.; Zhang, L. Generalized one-pot synthesis, characterization, and photocatalytic activity of hierarchical BiOX (X = Cl, Br, I) nanoplate microspheres. J. Phys. Chem. C 2008, 112, 747–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.B.; Chen, G.; Zhou, C.; Shen, Z.Y.; Jin, R.C.; Sun, J.X. New photocatalyst biocl/bioi composites with highly enhanced visible light photocatalytic performances. Dalton Trans. 2011, 40, 6751–6758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asahi, R.; Morikawa, T.; Ohwaki, T.; Aoki, K.; Taga, Y. Visible-light photocatalysis in nitrogen-doped titanium oxides. Science 2001, 293, 269–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ai, Z.; Ho, W.; Lee, S.; Zhang, L. Efficient photocatalytic removal of no in indoor air with hierarchical bismuth oxybromide nanoplate microspheres under visible light. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009, 43, 4143–4150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sing, K.S. Reporting physisorption data for gas/solid systems with special reference to the determination of surface area and porosity (recommendations 1984). Pure Appl. Chem. 1985, 57, 603–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Liu, Y.Z.; Wang, L.Q.; Ye, F. Low Temperature Preparation and Photocatalytic Activity Study of BiOI Powder. Environ. Prot. Sci. 2015, 41, 79–82. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.; Ai, Z.; Ho, W.; Chen, M.; Lee, S. Ultrasonic spray pyrolysis synthesis of porous Bi2WO6 microspheres and their visible-light-induced photocatalytic removal of NO. J. Phys. Chem. C 2010, 114, 6342–6349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.Z.; Yang, S.G.; Hong, J.; Sun, C. Low-temperature preparation and microwave photocatalytic activity study of TiO2-mounted activated carbon. J. Hazard. Mater. 2007, 142, 208–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, Y.; Laursen, A.B.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, G.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, X.; Dahl, S.; Chorkendorff, I. Layered nanojunctions for hydrogen-evolution catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 3621–3625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, K.; Chen, H.; Peng, T.; Ke, D.; Yi, H. Photocatalytic degradation of methyl orange in aqueous suspension of mesoporous titania nanoparticles. Chemosphere 2007, 69, 1361–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Liu, Y.; Liu, N.; Han, Y.; Zhang, X.; Huang, H.; Lifshitz, Y.; Lee, S.T.; Zhong, J.; Kang, Z. Water splitting. Metal-free efficient photocatalyst for stable visible water splitting via a two-electron pathway. Science 2015, 347, 970–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.C.; Lei, P.X.; Ji, H.W.; Ma, W.H.; Zhao, J.C. Photocatalysis by Titanium oxide and polyoxometalate/TiO2 cocatalysts. Intermediates and mechanistic study. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2004, 38, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.M.; Zhang, T.W.; Zeng, Y.W.; Hayakawa, S.; Tsuru, K.; Osaka, A. Large-scale preparation of ordered Titania nanonods with enhanced photocatalytic activity. Langmuir 2005, 21, 6995–7002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.X.; Wang, D.G.; Zhou, X.; Li, C. A theoretical study on the mechanism of photocatalytic oxygen evolution on BiVO4 in agueous solution. Chem. Eur. J. 2013, 19, 1320–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, R.; Imanishi, A.; Murakoshi, K.; Nakato, Y. In situ FTIR studies of primary intermediates of photocatalytic reactions on nanocrystalline TiO2 films in contact with aqueous solutions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 7443–7450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, W.; Guo, Y.; Wang, S.; He, H.; Sun, C.; Yang, S. A novel ternary plasmonic photocatalyst: Ultrathin g-C3N4 nanosheet hybrided by Ag/AgVO3 nanoribbons with enhanced visible-light photocatalytic performance. Appl. Catal. B 2015, 165, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Element | O 1s | Cl 2p | Bi 4f | I 3d |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atomic % | 30.57 | 2.44 | 22.03 | 7.09 |

| Catalyst | Surface Area/m2·g−1 | Pore Volume (cm3·g−1) | Pore Size (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| BiOI | 42.4 | 0.20 | 15.7 |

| BiOCl | 17.0 | 0.046 | 8.8 |

| BiOCl/BiOI | 37.7 | 0.20 | 16.8 |

| Light Irradiation | Photocatalysts | Kapp (min−1) | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| UV | BiOCl | 0.0022 | 0.979 |

| BiOBr | 0.0036 | 0.996 | |

| BiOI | 0.0036 | 0.998 | |

| BiOI/BiOBr | 0.0025 | 0.998 | |

| BiOI/BiOCl | 0.0044 | 0.998 | |

| Visible | BiOCl | 0.0016 | 0.976 |

| BiOBr | 0.0026 | 0.998 | |

| BiOI | 0.0050 | 0.999 | |

| BiOI/BiOBr | 0.0078 | 0.999 | |

| BiOI/BiOCl | 0.0100 | 0.999 |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, Y.; Xu, J.; Wang, L.; Zhang, H.; Xu, P.; Duan, X.; Sun, H.; Wang, S. Three-Dimensional BiOI/BiOX (X = Cl or Br) Nanohybrids for Enhanced Visible-Light Photocatalytic Activity. Nanomaterials 2017, 7, 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano7030064

Liu Y, Xu J, Wang L, Zhang H, Xu P, Duan X, Sun H, Wang S. Three-Dimensional BiOI/BiOX (X = Cl or Br) Nanohybrids for Enhanced Visible-Light Photocatalytic Activity. Nanomaterials. 2017; 7(3):64. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano7030064

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Yazi, Jian Xu, Liqiong Wang, Huayang Zhang, Ping Xu, Xiaoguang Duan, Hongqi Sun, and Shaobin Wang. 2017. "Three-Dimensional BiOI/BiOX (X = Cl or Br) Nanohybrids for Enhanced Visible-Light Photocatalytic Activity" Nanomaterials 7, no. 3: 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano7030064