Glycosyltransferases and Transpeptidases/Penicillin-Binding Proteins: Valuable Targets for New Antibacterials

Abstract

:1. Introduction

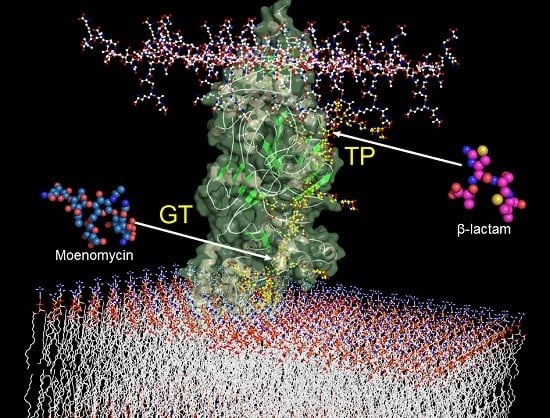

2. Penicillin-Binding Proteins: Classification, Structure and Function

3. Recent Developments in Transpeptidase Inhibitors

3.1. The β-Lactam Inhibitors of PBPs

3.1.1. Cephalosporins

3.1.2. Carbapenems

3.1.3. Monocyclic β-Lactams

3.2. Non-β-Lactams

3.3. Synergistic Combinations

4. Glycosyltrasferases Structure and Function

5. Synthesis of Lipid II and Analogous Substrates, and Their Use to Study the GT

6. Inhibitors of the Glycosyltrasferase

6.1. GT Inhibitors Based on Moenomycin and Lipid II Substrate

6.2. Glycosyltransferases Assays and Screening of Small Molecule Inhibitors

6.3. GT Inhibitor Identified by Structure-Based Virtual Screening

7. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vollmer, W.; Blanot, D.; de Pedro, M.A. Peptidoglycan structure and architecture. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2008, 32, 149–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouhss, A.; Trunkfield, A.E.; Bugg, T.D.; Mengin-Lecreulx, D. The biosynthesis of peptidoglycan lipid-linked intermediates. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2008, 32, 208–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terrak, M.; Ghosh, T.K.; van Heijenoort, J.; Van Beeumen, J.; Lampilas, M.; Aszodi, J.; Ayala, J.A.; Ghuysen, J.M.; Nguyen-Distèche, M. The catalytic, glycosyl transferase and acyl transferase modules of the cell wall peptidoglycan-polymerizing penicillin-binding protein 1b of Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 1999, 34, 350–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sauvage, E.; Kerff, F.F.; Terrak, M.; Ayala, J.A.; Charlier, P. The penicillin-binding proteins: Structure and role in peptidoglycan biosynthesis. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2008, 32, 234–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goffin, C.; Ghuysen, J.M. Multimodular penicillin-binding proteins: An enigmatic family of orthologs and paralogs. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 1998, 62, 1079–1093. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Banzhaf, M.; van den Berg van Saparoea, B.; Terrak, M.; Fraipont, C.; Egan, A.; Philippe, J.; Zapun, A.; Breukink, E.; Nguyen-Distèche, M.; den Blaauwen, T.; et al. Cooperativity of peptidoglycan synthases active in bacterial cell elongation. Mol. Microbiol. 2012, 85, 179–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lupoli, T.J.; Lebar, M.D.; Markovski, M.; Bernhardt, T.; Kahne, D.; Walker, S. Lipoprotein activators stimulate Escherichia coli penicillin-binding proteins by different mechanisms. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 52–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Born, P.; Breukink, E.; Vollmer, W. In vitro synthesis of cross-linked murein and its attachment to sacculi by PBP1A from Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 26985–26993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertsche, U.; Breukink, E.; Kast, T.; Vollmer, W. In vitro murein peptidoglycan synthesis by dimers of the bifunctional transglycosylase-transpeptidase PBP1B from Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 38096–38101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egan, A.J.F.; Biboy, J.; van’t Veer, I.; Breukink, E.; Vollmer, W. Activities and regulation of peptidoglycan synthases. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2015, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silver, L.L. Viable screening targets related to the bacterial cell wall. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2013, 1277, 29–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bush, K. A resurgence of β-lactamase inhibitor combinations effective against multidrug-resistant Gram-negative pathogens. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2015, 46, 483–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frère, J.-M.; Sauvage, E.; Kerff, F. From « An enzyme able to destroy penicillin » to carbapenemases: 70 years of beta-lactamase misbehavior. Curr. Drug Targets 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.-H.; Cohen, T.; Grad, Y.H.; Hanage, W.P.; O’Brien, T.F.; Lipsitch, M. Origin and proliferation of multiple-drug resistance in bacterial pathogens. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2015, 79, 101–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oppedijk, S.F.; Martin, N.I.; Breukink, E. Hit ’em where it hurts: The growing and structurally diverse family of peptides that target lipid-II. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Münch, D.; Sahl, H.-G. Structural variations of the cell wall precursor lipid II in Gram-positive bacteria—Impact on binding and efficacy of antimicrobial peptides. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2015, 1848, 3062–3071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, T.; Sahl, H.-G. Lipid II and other bactoprenol-bound cell wall precursors as drug targets. Curr. Opin. Investig. Drugs 2010, 11, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ling, L.L.; Schneider, T.; Peoples, A.J.; Spoering, A.L.; Engels, I.; Conlon, B.P.; Mueller, A.; Schäberle, T.F.; Hughes, D.E.; Epstein, S.; et al. A new antibiotic kills pathogens without detectable resistance. Nature 2015, 517, 455–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clardy, J.; Fischbach, M.A.; Walsh, C.T. New antibiotics from bacterial natural products. Nat. Biotechnol. 2006, 24, 1541–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nichols, D.; Cahoon, N.; Trakhtenberg, E.M.; Pham, L.; Mehta, A.; Belanger, A.; Kanigan, T.; Lewis, K.; Epstein, S.S. Use of ichip for high-throughput in situ cultivation of “uncultivable” microbial species. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010, 76, 2445–2450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Packiam, M.; Weinrick, B.; Jacobs, W.R.; Maurelli, A.T. Structural characterization of muropeptides from Chlamydia trachomatis peptidoglycan by mass spectrometry resolves “chlamydial anomaly”. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 11660–11665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liechti, G.W.; Kuru, E.; Hall, E.; Kalinda, A.; Brun, Y.V.; VanNieuwenhze, M.; Maurelli, A.T. A new metabolic cell-wall labelling method reveals peptidoglycan in Chlamydia trachomatis. Nature 2014, 506, 507–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zapun, A.; Vernet, T.; Pinho, M.G. The different shapes of cocci. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2008, 32, 345–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zapun, A.; Contreras-Martel, C.; Vernet, T. Penicillin-binding proteins and beta-lactam resistance. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2008, 32, 361–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slimings, C.; Riley, T.V. Antibiotics and hospital-acquired Clostridium difficile infection: Update of systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2014, 69, 881–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Heijenoort, J. Peptidoglycan hydrolases of Escherichia coli. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2011, 75, 636–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denome, S.A.; Elf, P.K.; Henderson, T.A.; Nelson, D.E.; Young, K.D. Escherichia coli mutants lacking all possible combinations of eight penicillin binding proteins: Viability, characteristics, and implications for peptidoglycan synthesis. J. Bacteriol. 1999, 181, 3981–3993. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vollmer, W.; Joris, B.; Charlier, P.; Foster, S. Bacterial peptidoglycan (murein) hydrolases. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2008, 32, 259–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarkar, S.K.; Chowdhury, C.; Ghosh, A.S. Deletion of penicillin-binding protein 5 (PBP5) sensitises Escherichia coli cells to beta-lactam agents. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2010, 35, 244–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dutta, M.; Kar, D.; Bansal, A.; Chakraborty, S.; Ghosh, A.S. A single amino acid substitution in the Ω-like loop of E. coli PBP5 disrupts its ability to maintain cell shape and intrinsic beta-lactam resistance. Microbiology 2015, 161, 895–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macheboeuf, P.; Contreras-Martel, C.; Job, V.; Dideberg, O.; Dessen, A. Penicillin binding proteins: Key players in bacterial cell cycle and drug resistance processes. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2006, 30, 673–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sauvage, E.; Derouaux, A.; Fraipont, C.; Joris, M.; Herman, R.; Rocaboy, M.; Schloesser, M.; Dumas, J.; Kerff, F.; Nguyen-Distèche, M.; et al. Crystal structure of penicillin-binding protein 3 (PBP3) from Escherichia coli. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e98042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertsche, U.; Kast, T.; Wolf, B.; Fraipont, C.; Aarsman, M.E.; Kannenberg, K.; von Rechenberg, M.; Nguyen-Distèche, M.; den Blaauwen, T.; Höltje, J.V.; et al. Interaction between two murein (peptidoglycan) synthases, PBP3 and PBP1B, in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 2006, 61, 675–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sung, M.T.; Lai, Y.T.; Huang, C.Y.; Chou, L.Y.; Shih, H.W.; Cheng, W.C.; Wong, C.H.; Ma, C. Crystal structure of the membrane-bound bifunctional transglycosylase PBP1b from Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 8824–8829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kishida, H.; Unzai, S.; Roper, D.I.; Lloyd, A.; Park, S.Y.; Tame, J.R. Crystal structure of penicillin binding protein 4 (dacB) from Escherichia coli, both in the native form and covalently linked to various antibiotics. Biochemistry 2006, 45, 783–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicholas, R.A.; Krings, S.; Tomberg, J.; Nicola, G.; Davies, C. Crystal structure of wild-type penicillin-binding protein 5 from Escherichia coli: Implications for deacylation of the acyl-enzyme complex. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 52826–52833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Typas, A.; Banzhaf, M.; van den Berg van Saparoea, B.; Verheul, J.; Biboy, J.; Nichols, R.J.; Zietek, M.; Beilharz, K.; Kannenberg, K.; von Rechenberg, M.; et al. Regulation of peptidoglycan synthesis by outer-membrane proteins. Cell 2010, 143, 1097–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paradis-Bleau, C.; Markovski, M.; Uehara, T.; Lupoli, T.J.; Walker, S.; Kahne, D.E.; Bernhardt, T.G. Lipoprotein cofactors located in the outer membrane activate bacterial cell wall polymerases. Cell 2010, 143, 1110–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pares, S.; Mouz, N.; Pétillot, Y.; Hakenbeck, R.; Dideberg, O. X-ray structure of Streptococcus pneumoniae PBP2x, a primary penicillin target enzyme. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1996, 3, 284–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maurer, P.; Todorova, K.; Sauerbier, J.; Hakenbeck, R. Mutations in Streptococcus pneumoniae penicillin-binding protein 2x: Importance of the C-terminal penicillin-binding protein and serine/threonine kinase-associated domains for beta-lactam binding. Microb. Drug Resist. 2012, 18, 314–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schweizer, I.; Peters, K.; Stahlmann, C.; Hakenbeck, R.; Denapaite, D. Penicillin-binding protein 2x of Streptococcus pneumoniae: The mutation Ala707Asp within the C-terminal PASTA2 domain leads to destabilization. Microb. Drug Resist. 2014, 20, 250–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, K.; Schweizer, I.; Beilharz, K.; Stahlmann, C.; Veening, J.-W.; Hakenbeck, R.; Denapaite, D. Streptococcus pneumoniae PBP2x mid-cell localization requires the C-terminal PASTA domains and is essential for cell shape maintenance. Mol. Microbiol. 2014, 92, 733–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sieradzki, K.; Pinho, M.G.; Tomasz, A. Inactivated pbp4 in highly glycopeptide-resistant laboratory mutants of Staphylococcus aureus. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 18942–18946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zapun, A.; Philippe, J.; Abrahams, K.A.; Signor, L.; Roper, D.I.; Breukink, E.; Vernet, T. In vitro reconstitution of peptidoglycan assembly from the Gram-positive pathogen Streptococcus pneumoniae. ACS Chem. Biol. 2013, 8, 2688–2696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lebar, M.D.; May, J.M.; Meeske, A.J.; Leiman, S.A.; Lupoli, T.J.; Tsukamoto, H.; Losick, R.; Rudner, D.Z.; Walker, S.; Kahne, D. Reconstitution of peptidoglycan cross-linking leads to improved fluorescent probes of cell wall synthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 10874–10877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levefaudes, M.; Patin, D.; de Sousa-d’Auria, C.; Chami, M.; Blanot, D.; Hervé, M.; Arthur, M.; Houssin, C.; Mengin-Lecreulx, D. Diaminopimelic Acid Amidation in Corynebacteriales: New insights into the role of ltsa in peptidoglycan modification. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 13079–13094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mainardi, J.-L.; Villet, R.; Bugg, T.D.; Mayer, C.; Arthur, M. Evolution of peptidoglycan biosynthesis under the selective pressure of antibiotics in Gram-positive bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2008, 32, 386–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiao, Y.; Lebar, M.D.; Schirner, K.; Schaefer, K.; Tsukamoto, H.; Kahne, D.; Walker, S. Detection of lipid-linked peptidoglycan precursors by exploiting an unexpected transpeptidase reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 14678–81461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pollock, J.J.; Ghuysen, J.M.; Linder, R.; Salton, M.R.; Perkins, H.R.; Nieto, M.; Leyh-Bouille, M.; Frere, J.M.; Johnson, K. Transpeptidase activity of Streptomyces d-alanyl-d carboxypeptidases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1972, 69, 662–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen-Distèche, M.; Leyh-Bouille, M.; Ghuysen, J.M. Isolation of the membrane-bound 26 000-Mr penicillin-binding protein of Streptomyces strain K15 in the form of a penicillin-sensitive d-alanyl-d-alanine-cleaving transpeptidase. Biochem. J. 1982, 207, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adam, M.; Damblon, C.; Jamin, M.; Zorzi, W.; Dusart, V.; Galleni, M.; el Kharroubi, A.; Piras, G.; Spratt, B.G.; Keck, W.; et al. Acyltransferase activities of the high-molecular-mass essential penicillin-binding proteins. Biochem. J. 1991, 279, 601–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Pedro, M.A.; Quintela, J.C.; Höltje, J.V.; Schwarz, H. Murein segregation in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1997, 179, 2823–2834. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lupoli, T.J.; Tsukamoto, H.; Doud, E.H.; Wang, T.-S.A.; Walker, S.; Kahne, D. Transpeptidase-mediated incorporation of d-amino acids into bacterial peptidoglycan. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 10748–10751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Dam, V.; Olrichs, N.; Breukink, E. Specific labeling of peptidoglycan precursors as a tool for bacterial cell wall studies. Chembiochem 2009, 10, 617–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuru, E.; Hughes, H.V.; Brown, P.J.; Hall, E.; Tekkam, S.; Cava, F.; de Pedro, M.A.; Brun, Y.V.; VanNieuwenhze, M.S. In Situ probing of newly synthesized peptidoglycan in live bacteria with fluorescent d-amino acids. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2012, 51, 12519–12523. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tipper, D.J.; Strominger, J.L. Mechanism of action of penicillins: A proposal based on their structural similarity to acyl-d-alanyl-d-alanine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1965, 54, 1133–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mpenge, M.A.; MacGowan, A.P. Ceftaroline in the management of complicated skin and soft tissue infections and community acquired pneumonia. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 2015, 11, 565–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghamrawi, R.J.; Neuner, E.; Rehm, S.J. Ceftaroline fosamil: A super-cephalosporin? Cleve. Clin. J. Med. 2015, 82, 437–444. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Davies, T.A.; Flamm, R.K.; Lynch, A.S. Activity of ceftobiprole against Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates exhibiting high-level resistance to ceftriaxone. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2012, 39, 534–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villegas-Estrada, A.; Lee, M.; Hesek, D.; Vakulenko, S.B.; Mobashery, S. Co-opting the cell wall in fighting methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: Potent inhibition of PBP 2a by two anti-MRSA beta-lactam antibiotics. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 9212–9213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hebeisen, P.; Heinze-Krauss, I.; Angehrn, P.; Hohl, P.; Page, M.G.; Then, R.L. In vitro and in vivo properties of Ro 63-9141, a novel broad-spectrum cephalosporin with activity against methicillin-resistant staphylococci. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2001, 45, 825–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henry, X.; Amoroso, A.; Coyette, J.; Joris, B. Interaction of ceftobiprole with the low-affinity PBP 5 of Enterococcus faecium. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2010, 54, 953–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henry, X.; Verlaine, O.; Amoroso, A.; Coyette, J.; Frere, J.M.; Joris, B. Activity of ceftaroline against Enterococcus faecium PBP5. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2013, 57, 6358–6360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zervosen, A.; Zapun, A.; Frère, J.-M. Inhibition of Streptococcus pneumoniae penicillin-binding protein 2x and Actinomadura R39 dd-peptidase activities by ceftaroline. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2013, 57, 661–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosowska-Shick, K.; McGhee, P.L.; Appelbaum, P.C. Affinity of ceftaroline and other beta-lactams for penicillin-binding proteins from Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2010, 54, 1670–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lovering, A.L.; Gretes, M.C.; Safadi, S.S.; Danel, F.; De Castro, L.; Page, M.G.; Strynadka, N.C. Structural Insights into the Anti- Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) Activity of Ceftobiprole. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 32096–32102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otero, L.H.; Rojas-Altuve, A.; Llarrull, L.I.; Carrasco-López, C.; Kumarasiri, M.; Lastochkin, E.; Fishovitz, J.; Dawley, M.; Hesek, D.; Lee, M.; et al. How allosteric control of Staphylococcus aureus penicillin binding protein 2a enables methicillin resistance and physiological function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 16808–16813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fishovitz, J.; Rojas-Altuve, A.; Otero, L.H.; Dawley, M.; Carrasco-López, C.; Chang, M.; Hermoso, J.A.; Mobashery, S. Disruption of allosteric response as an unprecedented mechanism of resistance to antibiotics. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 9814–9817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, D.; Strynadka, N.C. Structural basis for the beta lactam resistance of PBP2a from methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2002, 9, 870–876. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sauvage, E.; Kerff, F.; Fonze, E.; Herman, R.; Schoot, B.; Marquette, J.P.; Taburet, Y.; Prevost, D.; Dumas, J.; Leonard, G.; et al. The 2.4-A crystal structure of the penicillin-resistant penicillin-binding protein PBP5fm from Enterococcus faecium in complex with benzylpenicillin. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2002, 59, 1223–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelley, W.L.; Jousselin, A.; Barras, C.; Lelong, E.; Renzoni, A. Missense mutations in PBP2A Affecting ceftaroline susceptibility detected in epidemic hospital-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clonotypes ST228 and ST247 in Western Switzerland archived since Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015, 59, 1922–1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alm, R.A.; McLaughlin, R.E.; Kos, V.N.; Sader, H.S.; Iaconis, J.P.; Lahiri, S.D. Analysis of Staphylococcus aureus clinical isolates with reduced susceptibility to ceftaroline: An epidemiological and structural perspective. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2014, 69, 2065–2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, S.W.; Olsen, R.J.; Mehta, S.C.; Palzkill, T.; Cernoch, P.L.; Perez, K.K.; Musick, W.L.; Rosato, A.E.; Musser, J.M. PBP2a mutations causing high-level Ceftaroline resistance in clinical methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014, 58, 6668–6674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lahiri, S.D.; McLaughlin, R.E.; Whiteaker, J.D.; Ambler, J.E.; Alm, R.A. Molecular characterization of MRSA isolates bracketing the current EUCAST ceftaroline-susceptible breakpoint for Staphylococcus aureus: The role of PBP2a in the activity of ceftaroline. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2015, 70, 2488–2498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rybkine, T.; Mainardi, J.L.; Sougakoff, W.; Collatz, E.; Gutmann, L. Penicillin-binding protein 5 sequence alterations in clinical isolates of Enterococcus faecium with different levels of beta-lactam resistance. J. Infect. Dis. 1998, 178, 159–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fedarovich, A.; Cook, E.; Tomberg, J.; Nicholas, R.A.; Davies, C. Structural effect of the Asp345a insertion in penicillin-binding protein 2 from penicillin-resistant strains of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Biochemistry 2014, 53, 7596–7603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, S.; Zaniewski, R.P.; Marr, E.S.; Lacey, B.M.; Tomaras, A.P.; Evdokimov, A.; Miller, J.R.; Shanmugasundaram, V. Structural basis for effectiveness of siderophore-conjugated monocarbams against clinically relevant strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 22002–22007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, S.; Caspers, N.; Zaniewski, R.P.; Lacey, B.M.; Tomaras, A.P.; Feng, X.; Geoghegan, K.F.; Shanmugasundaram, V. Distinctive attributes of beta-lactam target proteins in Acinetobacter baumannii relevant to development of new antibiotics. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 20536–20545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sainsbury, S.; Bird, L.; Rao, V.; Shepherd, S.M.; Stuart, D.I.; Hunter, W.N.; Owens, R.J.; Ren, J. Crystal structures of penicillin-binding protein 3 from Pseudomonas aeruginosa: Comparison of native and antibiotic-bound forms. J. Mol. Biol. 2011, 405, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Berkel, S.S.; Nettleship, J.E.; Leung, I.K.H.; Brem, J.; Choi, H.; Stuart, D.I.; Claridge, T.D.W.; McDonough, M.A.; Owens, R.J.; Ren, J.; et al. Binding of (5S)-penicilloic acid to penicillin binding protein 3. ACS Chem. Biol. 2013, 8, 2112–2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trehan, I.; Morandi, F.; Blaszczak, L.C.; Shoichet, B.K. Using Steric Hindrance to Design New Inhibitors of Class C β-Lactamases. Chem. Biol. 2002, 9, 971–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweizer, H.P. Mechanisms of antibiotic resistance in Burkholderia pseudomallei: Implications for treatment of melioidosis. Future Microbiol. 2012, 7, 1389–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alm, R.A.; Johnstone, M.R.; Lahiri, S.D. Characterization of Escherichia coli NDM isolates with decreased susceptibility to aztreonam/avibactam: Role of a novel insertion in PBP3. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2015, 70, 1420–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomberg, J.; Temple, B.; Fedarovich, A.; Davies, C.; Nicholas, R.A. A highly conserved interaction involving the middle residue of the SXN active-site motif is crucial for function of class B penicillin-binding proteins: Mutational and computational analysis of PBP 2 from N. gonorrhoeae. Biochemistry 2012, 51, 2775–2784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maiden, M.C. Horizontal genetic exchange, evolution, and spread of antibiotic resistance in bacteria. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1998, 27 (Suppl. 1), S12–S20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sumita, Y.; Fukasawa, M. Potent activity of meropenem against Escherichia coli arising from its simultaneous binding to penicillin-binding proteins 2 and 3. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 1995, 36, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, T.A.; Shang, W.; Bush, K.; Flamm, R.K. Affinity of doripenem and comparators to penicillin-binding proteins in Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2008, 52, 1510–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mainardi, J.-L.; Hugonnet, J.-E.; Rusconi, F.; Fourgeaud, M.; Dubost, L.; Moumi, A.N.; Delfosse, V.; Mayer, C.; Gutmann, L.; Rice, L.B.; et al. Unexpected inhibition of peptidoglycan ld-transpeptidase from Enterococcus faecium by the beta-lactam imipenem. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 30414–30422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Triboulet, S.; Dubée, V.; Lecoq, L.; Bougault, C.; Mainardi, J.-L.; Rice, L.B.; Ethève-Quelquejeu, M.; Gutmann, L.; Marie, A.; Dubost, L.; et al. Kinetic features of l,d-transpeptidase inactivation critical for β-lactam antibacterial activity. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e67831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lecoq, L.; Dubée, V.; Triboulet, S.; Bougault, C.; Hugonnet, J.-E.; Arthur, M.; Simorre, J.-P. Structure of Enterococcus faeciuml,d-transpeptidase acylated by ertapenem provides insight into the inactivation mechanism. ACS Chem. Biol. 2013, 8, 1140–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Correale, S.; Ruggiero, A.; Capparelli, R.; Pedone, E.; Berisio, R. Structures of free and inhibited forms of the l,d-transpeptidase LdtMt1 from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2013, 69, 1697–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schanda, P.; Triboulet, S.; Laguri, C.; Bougault, C.M.; Ayala, I.; Callon, M.; Arthur, M.; Simorre, J.-P. Atomic model of a cell-wall cross-linking enzyme in complex with an intact bacterial peptidoglycan. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 17852–17860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lavollay, M.; Arthur, M.; Fourgeaud, M.; Dubost, L.; Marie, A.; Veziris, N.; Blanot, D.; Gutmann, L.; Mainardi, J.-L. The peptidoglycan of stationary-phase Mycobacterium tuberculosis predominantly contains cross-links generated by l,d-transpeptidation. J. Bacteriol. 2008, 190, 4360–4366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chowdhury, A.; Paul, P.; Bhattacharjee, A.; Talukdar, A. Das; Choudhury, M.D. Virtual high throughput screening of carbapenem derivatives as new generation carbapenemase and penicillin binding protein inhibitors: A hunt to save drug of last resort. Comb. Chem. High Throughput Screen. 2015, 18, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamachika, S.; Sugihara, C.; Kamai, Y.; Yamashita, M. Correlation between penicillin-binding protein 2 mutations and carbapenem resistance in Escherichia coli. J. Med. Microbiol. 2013, 62, 429–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aissa, N.; Mayer, N.; Bert, F.; Labia, R.; Lozniewski, A.; Nicolas-Chanoine, M.-H. A new mechanism to render clinical isolates of Escherichia coli non-susceptible to imipenem: Substitutions in the PBP2 penicillin-binding domain. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2015, 71, 76–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.G.P.; Dantier, C.; Desarbre, E. In vitro properties of BAL30072, a novel siderophore sulfactam with activity against multiresistant gram-negative bacilli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2010, 54, 2291–2302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landman, D.; Singh, M.; El-Imad, B.; Miller, E.; Win, T.; Quale, J. In vitro activity of the siderophore monosulfactam BAL30072 against contemporary Gram-negative pathogens from New York City, including multidrug-resistant isolates. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2014, 43, 527–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, P.G.; Stefanik, D.; Page, M.G.P.; Hackel, M.; Seifert, H. In vitro activity of the siderophore monosulfactam BAL30072 against meropenem-non-susceptible Acinetobacter baumannii. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2012, 67, 1167–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russo, T.A.; Page, M.G.P.; Beanan, J.M.; Olson, R.; Hujer, A.M.; Hujer, K.M.; Jacobs, M.; Bajaksouzian, S.; Endimiani, A.; Bonomo, R.A. In vivo and in vitro activity of the siderophore monosulfactam BAL30072 against Acinetobacter baumannii. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2011, 66, 867–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flanagan, M.E.; Brickner, S.J.; Lall, M.; Casavant, J.; Deschenes, L.; Finegan, S.M.; George, D.M.; Granskog, K.; Hardink, J.R.; Huband, M.D.; et al. Preparation, gram-negative antibacterial activity, and hydrolytic stability of novel siderophore-conjugated monocarbam diols. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2011, 2, 385–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy-Benenato, K.E.; Dangel, B.; Davis, H.E.; Durand-Réville, T.F.; Ferguson, A.D.; Gao, N.; Jahić, H.; Mueller, J.P.; Manyak, E.L.; Quiroga, O.; et al. SAR and Structural Analysis of Siderophore-Conjugated Monocarbam Inhibitors of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PBP3. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2015, 6, 537–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, A.; Kutschke, A.; Ehmann, D.E.; Patey, S.A.; Crandon, J.L.; Gorseth, E.; Miller, A.A.; McLaughlin, R.E.; Blinn, C.M.; Chen, A.; et al. Pharmacodynamic Profiling of a Siderophore-Conjugated Monocarbam in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: Assessing the Risk for Resistance and Attenuated Efficacy. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015, 59, 7743–7752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zervosen, A.; Sauvage, E.; Frère, J.M.; Charlier, P.; Luxen, A. Development of new drugs for an old target—The penicillin binding proteins. Molecules 2012, 17, 12478–12505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamura, N.; Matsushita, Y.; Kawano, Y.; Yoshioka, K. Synthesis and antibacterial activity of lactivicin derivatives. Chem. Pharm. Bull. (Tokyo) 1990, 38, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, T.; Charlier, P.; Herman, R.; Schofield, C.J.; Sauvage, E. Structural basis for the interaction of lactivicins with serine β-lactamases. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 53, 5890–5894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macheboeuf, P.; Fischer, D.S.; Brown, T., Jr.; Zervosen, A.; Luxen, A.; Joris, B.; Dessen, A.; Schofield, C.J. Structural and mechanistic basis of penicillin-binding protein inhibition by lactivicins. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2007, 3, 565–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Starr, J.; Brown, M.F.; Aschenbrenner, L.; Caspers, N.; Che, Y.; Gerstenberger, B.S.; Huband, M.; Knafels, J.D.; Lemmon, M.M.; Li, C.; et al. Siderophore receptor-mediated uptake of lactivicin analogues in gram-negative bacteria. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 3845–3855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dzhekieva, L.; Rocaboy, M.; Kerff, F.; Charlier, P.; Sauvage, E.; Pratt, R.F. Crystal structure of a complex between the actinomadura R39 dd -peptidase and a peptidoglycan-mimetic boronate inhibitor: Interpretation of a transition state analogue in terms of catalytic mechanism. Biochemistry 2010, 49, 6411–6419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dzhekieva, L.; Adediran, S.A.; Herman, R.; Kerff, F.; Duez, C.; Charlier, P.; Sauvage, E.; Pratt, R.F. Inhibition of dd-peptidases by a specific trifluoroketone: Crystal structure of a complex with the Actinomadura R39 dd-peptidase. Biochemistry 2013, 52, 2128–2138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Contreras-Martel, C.; Amoroso, A.; Woon, E.C.; Zervosen, A.; Inglis, S.; Martins, A.; Verlaine, O.; Rydzik, A.M.; Job, V.; Luxen, A.; et al. Structure-guided design of cell wall biosynthesis inhibitors that overcome beta-lactam resistance in Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). ACS Chem. Biol. 2011, 6, 943–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dzhekieva, L.; Kumar, I.; Pratt, R.F. Inhibition of bacterial dd-peptidases (penicillin-binding proteins) in membranes and in vivo by peptidoglycan-mimetic boronic acids. Biochemistry 2012, 51, 2804–2811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delmas, J.; Chen, Y.; Prati, F.; Robin, F.; Shoichet, B.K.; Bonnet, R. Structure and dynamics of CTX-M enzymes reveal insights into substrate accommodation by extended-spectrum beta-lactamases. J. Mol. Biol. 2008, 375, 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irwin, J.J.; Sterling, T.; Mysinger, M.M.; Bolstad, E.S.; Coleman, R.G. ZINC: A free tool to discover chemistry for biology. J. Chem. Inf. Model 2012, 52, 1757–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Daniel, P.I.; Peng, Z.; Pi, H.; Testero, S.A.; Ding, D.; Spink, E.; Leemans, E.; Boudreau, M.A.; Yamaguchi, T.; Schroeder, V.A.; et al. Discovery of a new class of non-β-lactam inhibitors of penicillin-binding proteins with Gram-positive antibacterial activity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 3664–3672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spink, E.; Ding, D.; Peng, Z.; Boudreau, M.A.; Leemans, E.; Lastochkin, E.; Song, W.; Lichtenwalter, K.; O’Daniel, P.I.; Testero, S.A.; et al. Structure-activity relationship for the oxadiazole class of antibiotics. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 58, 1380–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dive, G.; Bouillon, C.; Sliwa, A.; Valet, B.; Verlaine, O.; Sauvage, E.; Marchand-Brynaert, J. Macrocycle-embedded β-lactams as novel inhibitors of the Penicillin Binding Protein PBP2a from MRSA. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 64, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rani, N.; Saravanan, V.; Lakshmi, P.T.V.; Arunachalam, A. Allosteric site mediated active site inhibition of PBP2a using Quercetin 3-O-Rutinoside and its combination. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2015, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavanya, P.; Ramaiah, S.; Anbarasu, A. A Molecular Docking and Dynamics Study to Screen Potent Anti-Staphylococcal Compounds Against Ceftaroline Resistant MRSA. J. Cell. Biochem. 2015, 117, 542–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fedarovich, A.; Djordjevic, K.A.; Swanson, S.M.; Peterson, Y.K.; Nicholas, R.A.; Davies, C. High-throughput screening for novel inhibitors of Neisseria gonorrhoeae penicillin-binding protein 2. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e44918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, G.; Meier, T.I.; Kahl, S.D.; Gee, K.R.; Blaszczak, L.C. BOCILLIN FL, a sensitive and commercially available reagent for detection of penicillin-binding proteins. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1999, 43, 1124–1128. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- English, B.K. Limitations of beta-lactam therapy for infections caused by susceptible Gram-positive bacteria. J. Infect. 2014, 69 (Suppl. 1), S5–S9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahme, C.; Butterfield, J.M.; Nicasio, A.M.; Lodise, T.P. Dual beta-lactam therapy for serious Gram-negative infections: Is it time to revisit? Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2014, 80, 239–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banerjee, R.; Fernandez, M.G.; Enthaler, N.; Graml, C.; Greenwood-Quaintance, K.E.; Patel, R. Combinations of cefoxitin plus other β-lactams are synergistic in vitro against community associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2013, 32, 827–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzales, P.R.; Pesesky, M.W.; Bouley, R.; Ballard, A.; Biddy, B.A.; Suckow, M.A.; Wolter, W.R.; Schroeder, V.A.; Burnham, C.-A.D.; Mobashery, S.; et al. Synergistic, collaterally sensitive β-lactam combinations suppress resistance in MRSA. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2015, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, J.-Z. Methicillin/per-6-(4-methoxylbenzyl)-amino-6-deoxy-β-cyclodextrin 1:1 complex and its potentiation in vitro against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J. Antibiot. (Tokyo) 2013, 66, 517–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Río, A.; García-de-la-Mària, C.; Entenza, J.M.; Gasch, O.; Armero, Y.; Soy, D.; Mestres, C.A.; Pericás, J.M.; Falces, C.; Ninot, S.; et al. Fosfomycin plus Beta-lactams: Synergistic Bactericidal Combinations in Methicillin-resistant (MRSA) and Glycopeptide-Intermediate Resistant (GISA) Staphylococcus aureus Experimental Endocarditis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015, 60, 478–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nair, D.R.; Monteiro, J.M.; Memmi, G.; Thanassi, J.; Pucci, M.; Schwartzman, J.; Pinho, M.G.; Cheung, A.L. Characterization of a Novel Small Molecule That Potentiates β-Lactam Activity against Gram-Positive and Gram-Negative Pathogens. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015, 59, 1876–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guignard, B.; Vouillamoz, J.; Giddey, M.; Moreillon, P. A positive interaction between inhibitors of protein synthesis and cefepime in the fight against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2013, 32, 899–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lovering, A.L.; de Castro, L.H.; Lim, D.; Strynadka, N.C. Structural insight into the transglycosylation step of bacterial cell-wall biosynthesis. Science 2007, 315, 1402–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Y.; Barrett, D.; Zhang, Y.; Kahne, D.; Sliz, P.; Walker, S. Crystal structure of a peptidoglycan glycosyltransferase suggests a model for processive glycan chain synthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 5348–5353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heaslet, H.; Shaw, B.; Mistry, A.; Miller, A.A. Characterization of the active site of S. aureus monofunctional glycosyltransferase (Mtg) by site-directed mutation and structural analysis of the protein complexed with moenomycin. J. Struct. Biol. 2009, 167, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.Y.; Shih, H.W.; Lin, L.Y.; Tien, Y.W.; Cheng, T.J.; Cheng, W.C.; Wong, C.H.; Ma, C. Crystal structure of Staphylococcus aureus transglycosylase in complex with a lipid II analog and elucidation of peptidoglycan synthesis mechanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 6496–6501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terrak, M.; Sauvage, E.; Derouaux, A.; Dehareng, D.; Bouhss, A.; Breukink, E.; Jeanjean, S.; Nguyen-Distèche, M. Importance of the conserved residues in the peptidoglycan glycosyltransferase module of the class A penicillin-binding protein 1b of Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 28464–28470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Y.; Fuse, S.; Ostash, B.; Sliz, P.; Kahne, D.; Walker, S. Structural analysis of the contacts anchoring moenomycin to peptidoglycan glycosyltransferases and implications for antibiotic design. ACS Chem. Biol. 2008, 3, 429–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lovering, A.L.; De Castro, L.; Strynadka, N.C. Identification of dynamic structural motifs involved in peptidoglycan glycosyltransfer. J. Mol. Biol. 2008, 383, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bury, D.; Dahmane, I.; Derouaux, A.; Dumbre, S.; Herdewijn, P.; Matagne, A.; Breukink, E.; Mueller-Seitz, E.; Petz, M.; Terrak, M. Positive cooperativity between acceptor and donor sites of the peptidoglycan glycosyltransferase. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2015, 93, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.-S.A.; Lupoli, T.J.; Sumida, Y.; Tsukamoto, H.; Wu, Y.; Rebets, Y.; Kahne, D.E.; Walker, S. Primer preactivation of peptidoglycan polymerases. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 8528–8530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yunck, R.; Cho, H.; Bernhardt, T.G. Identification of MltG as a potential terminase for peptidoglycan polymerization in bacteria. Mol. Microbiol. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.-S.A.; Manning, S.A.; Walker, S.; Kahne, D. Isolated peptidoglycan glycosyltransferases from different organisms produce different glycan chain lengths. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 14068–14069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Offant, J.; Terrak, M.; Derouaux, A.; Breukink, E.; Nguyen-Distèche, M.; Zapun, A.; Vernet, T. Optimization of conditions for the glycosyltransferase activity of penicillin-binding protein 1a from Thermotoga maritima. FEBS J. 2010, 277, 4290–4298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, B.; Markwalder, J.A.; Wang, Y. Lipid II: Total synthesis of the bacterial cell wall precursor and utilization as a substrate for glycosyltransfer and transpeptidation by penicillin binding protein (PBP) 1b of Escherichia coli. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001, 123, 11638–11643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, B.; Markwalder, J.A.; Seitz, S.P.; Wang, Y.; Stein, R.L. A kinetic characterization of the glycosyltransferase activity of Eschericia coli PBP1b and development of a continuous fluorescence assay. Biochemistry 2002, 41, 12552–12561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- VanNieuwenhze, M.S.; Mauldin, S.C.; Zia-Ebrahimi, M.; Winger, B.E.; Hornback, W.J.; Saha, S.L.; Aikins, J.A.; Blaszczak, L.C. The first total synthesis of lipid II: The final monomeric intermediate in bacterial cell wall biosynthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 3656–3660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, X.Y.; Lo, M.C.; Brunner, L.; Walker, D.; Kahne, D.; Walker, S. Better substrates for bacterial transglycosylases. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001, 123, 3155–3156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Fechter, E.J.; Wang, T.S.; Barrett, D.; Walker, S.; Kahne, D.E. Synthesis of heptaprenyl-lipid IV to analyze peptidoglycan glycosyltransferases. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 3080–3081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gampe, C.M.; Tsukamoto, H.; Wang, T.S.; Walker, S.; Kahne, D. Modular synthesis of diphospholipid oligosaccharide fragments of the bacterial cell wall and their use to study the mechanism of moenomycin and other antibiotics. Tetrahedron 2011, 67, 9771–9778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shih, H.-W.; Chen, K.-T.; Cheng, T.-J.R.; Wong, C.-H.; Cheng, W.-C. A new synthetic approach toward bacterial transglycosylase substrates, Lipid II and Lipid IV. Org. Lett. 2011, 13, 4600–4603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Heijenoort, Y.; Gomez, M.; Derrien, M.; Ayala, J.; van Heijenoort, J. Membrane intermediates in the peptidoglycan metabolism of Escherichia coli: Possible roles of PBP 1b and PBP 3. J. Bacteriol. 1992, 174, 3549–3557. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Breukink, E.; van Heusden, H.E.; Vollmerhaus, P.J.; Swiezewska, E.; Brunner, L.; Walker, S.; Heck, A.J.; de Kruijff, B. Lipid II is an intrinsic component of the pore induced by nisin in bacterial membranes. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 19898–19903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, L.-Y.; Huang, S.-H.; Chang, Y.-C.; Cheng, W.-C.; Cheng, T.-J.R.; Wong, C.-H. Enzymatic synthesis of lipid II and analogues. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2014, 53, 8060–8065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranjan, R.; Marczewski, A.; Chojnacki, T.; Hertel, J.; Swiezewska, E. Search for polyprenols in leaves of evergreen and deciduous Ericaceae plants. Acta Biochim. Pol. 2001, 48, 579–584. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Perlstein, D.L.; Wang, T.S.; Doud, E.H.; Kahne, D.; Walker, S. The role of the substrate lipid in processive glycan polymerization by the peptidoglycan glycosyltransferases. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 48–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.-Y.; Guo, C.-W.; Chang, Y.-F.; Wang, J.-T.; Shih, H.-W.; Hsu, Y.-F.; Chen, C.-W.; Chen, S.-K.; Wang, Y.-C.; Cheng, T.-J.R.; et al. Synthesis and evaluation of a new fluorescent transglycosylase substrate: Lipid II-based molecule possessing a dansyl-C20 polyprenyl moiety. Org. Lett. 2010, 12, 1608–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biboy, J.; Bui, N.K.; Vollmer, W. In vitro peptidoglycan synthesis assay with lipid II substrate. Methods Mol. Biol. 2013, 966, 273–288. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Huang, S.H.; Wu, W.S.; Huang, L.Y.; Huang, W.F.; Fu, W.C.; Chen, P.T.; Fang, J.M.; Cheng, W.C.; Cheng, T.J.; Wong, C.H. New continuous fluorometric assay for bacterial transglycosylase using Forster resonance energy transfer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 17078–17089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrett, D.; Wang, T.S.; Yuan, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Kahne, D.; Walker, S. Analysis of glycan polymers produced by peptidoglycan glycosyltransferases. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 31964–31971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dumbre, S.; Derouaux, A.; Lescrinier, E.; Piette, A.; Joris, B.; Terrak, M.; Herdewijn, P. Synthesis of modified peptidoglycan precursor analogues for the inhibition of glycosyltransferase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 9343–9351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mesleh, M.F.; Rajaratnam, P.; Conrad, M.; Chandrasekaran, V.; Liu, C.M.; Pandya, B.; Hwang, Y.S.; Rye, P.T.; Muldoon, C.; Becker, B.; et al. Targeting bacterial cell wall peptidoglycan synthesis by inhibition of glycosyltransferase activity. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2015, 87, 190–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuegg, J.; Muldoon, C.; Adamson, G.; McKeveney, D.; Le Thanh, G.; Premraj, R.; Becker, B.; Cheng, M.; Elliott, A.G.; Huang, J.X.; et al. Carbohydrate scaffolds as glycosyltransferase inhibitors with in vivo antibacterial activity. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 7719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.-K.; Chen, K.-T.; Hu, C.-M.; Yun, W.-Y.; Cheng, W.-C. Synthesis of 1-C-Glycoside-Linked Lipid II Analogues Toward Bacterial Transglycosylase Inhibition. Chemistry 2015, 21, 7511–7519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, C.-H.; Schelwies, M.; Enck, S.; Huang, L.-Y.; Huang, S.-H.; Chang, Y.-F.; Cheng, T.-J.R.; Cheng, W.-C.; Wong, C.-H. Iminosugar C-Glycoside Analogues of α- d -GlcNAc-1-Phosphate: Synthesis and Bacterial Transglycosylase Inhibition. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 79, 8629–8637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perlstein, D.L.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, T.S.; Kahne, D.E.; Walker, S. The direction of glycan chain elongation by peptidoglycan glycosyltransferases. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 12674–12675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fraipont, C.; Sapunaric, F.; Zervosen, A.; Auger, G.; Devreese, B.; Lioux, T.; Blanot, D.; Mengin-Lecreulx, D.; Herdewijn, P.; Van Beeumen, J.; et al. Glycosyl transferase activity of the Escherichia coli penicillin-binding protein 1b: Specificity profile for the substrate. Biochemistry 2006, 45, 4007–4013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shih, H.-W.; Chang, Y.-F.; Li, W.-J.; Meng, F.-C.; Huang, C.-Y.; Ma, C.; Cheng, T.-J.R.; Wong, C.-H.; Cheng, W.-C. Effect of the peptide moiety of Lipid II on bacterial transglycosylase. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2012, 51, 10123–10126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McPherson, D.C.; Popham, D.L. Peptidoglycan synthesis in the absence of class A penicillin-binding proteins in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 2003, 185, 1423–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arbeloa, A.; Segal, H.; Hugonnet, J.E.; Josseaume, N.; Dubost, L.; Brouard, J.P.; Gutmann, L.; Mengin-Lecreulx, D.; Arthur, M. Role of class A penicillin-binding proteins in PBP5-mediated beta-lactam resistance in Enterococcus faecalis. J. Bacteriol. 2004, 186, 1221–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welzel, P. Syntheses around the transglycosylation step in peptidoglycan biosynthesis. Chem Rev 2005, 105, 4610–4660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuse, S.; Tsukamoto, H.; Yuan, Y.; Wang, T.-S.A.; Zhang, Y.; Bolla, M.; Walker, S.; Sliz, P.; Kahne, D. Functional and structural analysis of a key region of the cell wall inhibitor moenomycin. ACS Chem. Biol. 2010, 5, 701–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostash, B.; Walker, S. Moenomycin family antibiotics: Chemical synthesis, biosynthesis, and biological activity. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2010, 27, 1594–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huber, G. Moenomycin and Related Phosphorus-Containing Antibiotics. In Mechanism of Action of Antibacterial Agents; Hahn, F., Ed.; Springer-Verlag Berlin: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1979; pp. 135–153. [Google Scholar]

- Pfaller, M.A. Flavophospholipol use in animals: Positive implications for antimicrobial resistance based on its microbiologic properties. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2006, 56, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, H.; van Heijenoort, Y.; Tamura, T.; Mizoguchi, J.; Hirota, Y.; van Heijenoort, J. In vitro peptidoglycan polymerization catalysed by penicillin binding protein 1b of Escherichia coli K-12. FEBS Lett. 1980, 110, 245–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Berardino, M.; Dijkstra, A.; Stuber, D.; Keck, W.; Gubler, M. The monofunctional glycosyltransferase of Escherichia coli is a member of a new class of peptidoglycan-synthesising enzymes. FEBS Lett. 1996, 392, 184–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butaye, P.; Devriese, L.A.; Haesebrouck, F. Influence of different medium components on the in vitro activity of the growth-promoting antibiotic flavomycin against enterococci. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2000, 46, 713–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rebets, Y.; Lupoli, T.; Qiao, Y.; Schirner, K.; Villet, R.; Hooper, D.; Kahne, D.; Walker, S. Moenomycin resistance mutations in Staphylococcus aureus reduce peptidoglycan chain length and cause aberrant cell division. ACS Chem. Biol. 2014, 9, 459–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reed, P.; Veiga, H.; Jorge, A.M.; Terrak, M.; Pinho, M.G. Monofunctional transglycosylases are not essential for Staphylococcus aureus cell wall synthesis. J. Bacteriol. 2011, 193, 2549–2556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derouaux, A.; Sauvage, E.; Terrak, M. Peptidoglycan glycosyltransferase substrate mimics as templates for the design of new antibacterial drugs. Front. Immunol. 2013, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramachandran, V.; Chandrakala, B.; Kumar, V.P.; Usha, V.; Solapure, S.M.; de Sousa, S.M. Screen for inhibitors of the coupled transglycosylase-transpeptidase of peptidoglycan biosynthesis in Escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2006, 50, 1425–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terrak, M.; Nguyen-Distèche, M. Kinetic characterization of the monofunctional glycosyltransferase from Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 2006, 188, 2528–2532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanchaert, B.; Wyseure, T.; Breukink, E.; Adams, E.; Declerck, P.; Van Schepdael, A. Development of a liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry assay for the bacterial transglycosylation reaction through measurement of Lipid II. Electrophoresis 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, T.J.; Sung, M.T.; Liao, H.Y.; Chang, Y.F.; Chen, C.W.; Huang, C.Y.; Chou, L.Y.; Wu, Y.D.; Chen, Y.H.; Cheng, Y.S.; et al. Domain requirement of moenomycin binding to bifunctional transglycosylases and development of high-throughput discovery of antibiotics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 431–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, T.-J.R.; Wu, Y.-T.; Yang, S.-T.; Lo, K.-H.; Chen, S.-K.; Chen, Y.-H.; Huang, W.-I.; Yuan, C.-H.; Guo, C.-W.; Huang, L.-Y.; et al. High-throughput identification of antibacterials against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and the transglycosylase. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2010, 18, 8512–8529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gampe, C.M.; Tsukamoto, H.; Doud, E.H.; Walker, S.; Kahne, D. Tuning the moenomycin pharmacophore to enable discovery of bacterial cell wall synthesis inhibitors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 3776–3779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, M; Zhou, M.; Zuo, Z.; Tang, X.; Liu, J.; Ma., X. Structure-based virtual screening for glycosyltrasferase51. Mol. Simul. 2008, 34, 849–856. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Chan, F.-Y.; Sun, N.; Lui, H.-K.; So, P.-K.; Yan, S.-C.; Chan, K.-F.; Chiou, J.; Chen, S.; Abagyan, R.; et al. Structure-based design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of isatin derivatives as potential glycosyltransferase inhibitors. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2014, 84, 685–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derouaux, A.; Turk, S.; Olrichs, N.K.; Gobec, S.; Breukink, E.; Amoroso, A.; Offant, J.; Bostock, J.; Mariner, K.; Chopra, I.; et al. Small molecule inhibitors of peptidoglycan synthesis targeting the lipid II precursor. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2011, 81, 1098–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sosic, I.; Anderluh, M.; Sova, M.; Gobec, M.; Mlinaric-Rascan, I.; Derouaux, A.; Amoroso, A.; Terrak, M.; Breukink, E.; Gobec, S. Structure-activity relationships of novel tryptamine-based inhibitors of bacterial transglycosylase. J. Med. Chem. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons by Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sauvage, E.; Terrak, M. Glycosyltransferases and Transpeptidases/Penicillin-Binding Proteins: Valuable Targets for New Antibacterials. Antibiotics 2016, 5, 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics5010012

Sauvage E, Terrak M. Glycosyltransferases and Transpeptidases/Penicillin-Binding Proteins: Valuable Targets for New Antibacterials. Antibiotics. 2016; 5(1):12. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics5010012

Chicago/Turabian StyleSauvage, Eric, and Mohammed Terrak. 2016. "Glycosyltransferases and Transpeptidases/Penicillin-Binding Proteins: Valuable Targets for New Antibacterials" Antibiotics 5, no. 1: 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics5010012