1. Introduction

Atopic eczema, synonymous with atopic dermatitis, is a common dermatological condition and in the top 50 of the most prevalent diseases worldwide [

1]. Management of atopic eczema takes place predominantly in primary care and topical corticosteroids are widely prescribed to provide symptomatic relief of this condition. The safety and efficacy of topical corticosteroids are well established, provided that these products are used according to guidelines. However, in reality, some patients, and perhaps even some prescribers and other healthcare professionals, still feel apprehensive about the safety of topical corticosteroids even when used appropriately [

2]. For example, patients or carers worry about skin thinning and systemic absorption leading to effects on growth and development. This situation remains, despite considerable efforts over many years by clinicians and researchers to highlight the therapeutic value and safety of topical corticosteroids when used correctly [

3,

4].

Fear and anxiety about applying topical corticosteroids is perhaps understandable if one considers the following contextual factors. Prescribing in dermatology can be seen as imprecise because often neither the patient nor the prescriber is certain about how much topical treatment to apply [

5]. Yet, patients rely heavily on the directions of their prescribers and the product literature in an effort to use topical corticosteroids correctly. The problem is compounded by the fact that most dispensed topical corticosteroid products carry labels that read ‘use as directed’ and ‘apply thinly’ as a norm. This in itself presents problems, as such instructions are subjective and ambiguous but, in the meantime, carry the connotation of being hazardous if not adhered to [

6,

7].

A number of studies have clearly shown that patients are not sufficiently advised by their healthcare professionals on topical corticosteroids and their use [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. Current evidence also indicates that the lack of patient education on topical corticosteroid use has had a negative impact on the treatment they receive [

12,

13]. Unjustified fears of topical corticosteroids interfere with patients’ adherence to treatment and potentially affect the treatment outcome. Such fears can potentially be overcome with effective patient education on topical corticosteroids, especially if targeted at changing core beliefs about topical corticosteroids [

12,

14]. This is a role that can be carried out by healthcare professionals, including community pharmacists.

Community pharmacists are well placed to ensure that patients have been adequately educated on their topical corticosteroids before treatment begins as they are often the health professionals that see the patient immediately before medication is provided to them [

15]. This role is doubly important considering that education about topical corticosteroid treatment is thought to be lacking from prescribers and manufacturers [

8,

10]. Even if the message regarding the correct application of topical treatments has been given by doctors and nurses, the pharmacist has an important role in reinforcing this message and ensuring that patients remember and understand what they have been told [

16]. It is also important to consider that some topical corticosteroids are available without prescription to self-medicating patients who may not have been seen by a prescriber at all. In such cases, the community pharmacist may be the only healthcare professional to have the opportunity to offer any patient counselling on topical corticosteroid use.

Appropriate educational intervention by pharmacists has been shown to effectively improve medication adherence [

15,

17,

18,

19]. This provides a strong rationale for advocating that community pharmacists play an active role in terms of educating patients who use topical corticosteroids, especially considering that adherence has been traditionally low in dermatology [

20]. Recently, a number of studies have investigated the role, personal views and diagnostic ability of the community pharmacist in dermatological conditions [

16,

21,

22] and their level of confidence in relation to topical corticosteroids [

23]. However, little is known about the relationship between the community pharmacist’s own knowledge and attitude towards information provision and their patient counselling behaviour. To investigate this important relationship, we designed, validated and conducted a survey that was informed by interviews, to examine community pharmacists’ knowledge, attitude towards information provision and self-reported patient counselling behaviour in relation to topical corticosteroids and adjunct therapy for the treatment of atopic eczema.

2. Materials and Methods

The study employed a sequential mixed-methods approach where face-to-face semi-structured interviews informed the design of a questionnaire. The questionnaire was validated and piloted before being sent to community pharmacists for completion and return. The study was approved by the University of Reading Research Ethics Committee (study number 15/12).

2.1. Semi-Structured Interviews

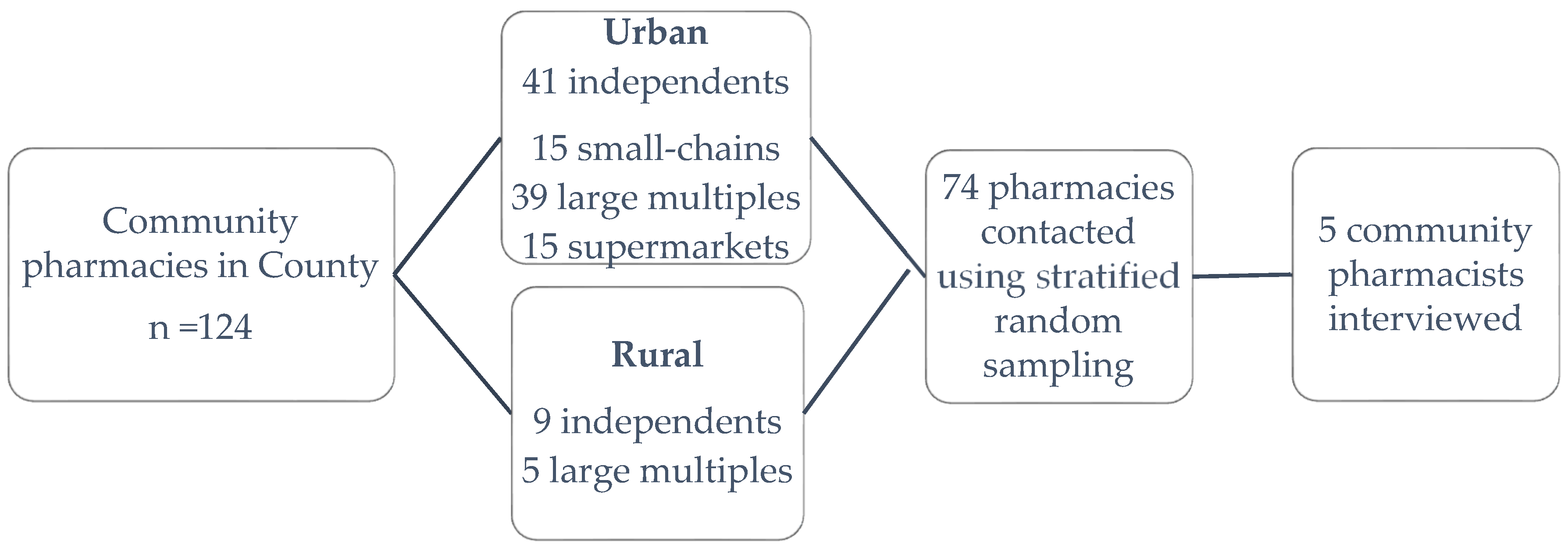

Stratified random sampling was used to invite pharmacists working in a range of settings to interview using addresses listed in a public NHS database of pharmacies for Berkshire (one English county) (

Figure 1). A total of 74 participant invitation letters were posted, with 12 or 13 going to each business type/location combination. The letter was addressed to ‘the pharmacist’ and invited them to a face-to-face interview about their views and ideas on the use of topical corticosteroids. A reminder letter was sent to pharmacies that had not responded after a month. Face-to-face, semi-structured interviews were conducted with the five community pharmacists (representing rural independent, urban independent and urban large multiple pharmacies) working in one English county who responded to the invitations. The interviewees each had between 13 and 34 years of community pharmacy experience. Each face-to-face interview was conducted in the setting of the interviewees’ pharmacy and lasted approximately 20 min.

Four pre-formulated vignettes were designed and validated during a preliminary phase, with a consortium of four pharmacists based at the School of Pharmacy (SOP). The vignettes were followed by a fixed number of questions that explored ideas about the cases further. Each vignette focussed on a different scenario likely to be encountered in a community pharmacy relating to skin conditions requiring a topical corticosteroid: (1) dispensing a topical corticosteroid prescription for an infant; (2) receiving a prescription for a potent topical corticosteroid; (3) addressing a customer’s request for an over-the-counter (OTC) topical corticosteroid based on a General Practitioner’s (GP’s) advice; (4) advice sought by a customer in relation to OTC topical corticosteroids (

Table 1). In the questions that followed, participants were invited to comment on the cases in detail.

Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim but anonymised and then analysed using thematic analysis. Major themes arising from the analyses were subsequently used for informing the design of the main questionnaire.

2.2. Questionnaire Design

A questionnaire was designed to explore knowledge, attitudes to information provision, and frequency of self-reported counselling behaviours of pharmacists in relation to the use of topical corticosteroids and adjunct therapy in atopic eczema within a community pharmacy setting. The relevant National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guideline [

24] and the British National Formulary (BNF) [

25] were used to devise 19 factual questions on the correct treatment of atopic eczema covering the five themes derived from the interviews. The five themes were:

non-pharmacological therapy, indication for use of topical corticosteroid (

topical corticosteroid indication), safety/effectiveness of topical corticosteroid (

topical corticosteroid safety), application/instructions of topical corticosteroid (

topical corticosteroid application) and

topical corticosteroid formulations (detailed in the results section). Matching attitude (towards providing patients with information related to the above 19 facts) and counselling behaviour (frequency of providing this information in practice) questions were then devised with the help of five SOP pharmacists who reviewed the questions and provided feedback.

A web-based survey was developed and formatted using Bristol Online Survey consisting of four sections: Section A: 19 factual (knowledge) questions with fixed-response of Yes, No or Don’t know options; Section B: 19 matching attitude questions presented in a random order with a five-point Likert response scales from strongly agree to strongly disagree; Section C: 19 matching counselling behaviour questions enquiring about frequency of advice provided with five-point Likert response scales ranging from never to always; and Section D: pharmacists’ demographics relating to gender, age, work responsibility and details of any additional training on dermatology treatments. The questionnaire was formatted so that participants had to answer all questions within a section before the next section appeared and once they had submitted one section, they were unable to return to the previous section to change their answers. The online questionnaire was tested again with two pharmacists within the SOP to assess face and content validity.

The internet link to the online questionnaire, a cover letter and a participant information letter were emailed to all 294 community pharmacists working within one medium-sized chain of community pharmacies, with branches covering mainly the South East, Central and West of England but with branches also in the North of England, in August 2015. This one pharmacy chain was targeted for expediency—through an established teacher-practitioner relationship with the chain, we were able to gain the support and approval of the superintendent pharmacist for the work to go ahead, learn about the total number of pharmacists employed by the chain (to calculate the response rate) and to email all the pharmacists (via a secondary contact). A reminder email was sent to all the pharmacists on 1 September 2015 and the data collection stopped on 30 September 2015. Data were extracted directly from the Bristol Online Survey into the Statistical Package for the Social Science (SPSS) (Version 21.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.) and analysed anonymously. Expert statistical advice was provided by Reading Statistical Services, which involved a statistician examining the questionnaire and the data generated extensively to advise on the suitable choice of analysis. Spearman rank correlation coefficient was used to evaluate the associations between attitude to information provision and self-reported counselling behaviour with the accepted level of statistical significance being p < 0.05.

4. Discussion

This is the first study that has used a mixed-methods approach to explore the counselling role of community pharmacists in the UK in relation to the use of topical corticosteroids in atopic eczema/atopic dermatitis. The face-to-face interviews provided insights about the types of knowledge pharmacists deemed important to communicate in topical corticosteroid related cases. Five main themes were derived and used to formulate a questionnaire to measure the general knowledge, attitude to information provision and self-reported frequency of counselling behaviour of a wider group of community pharmacists in relation to the use of topical corticosteroids and adjunct treatment. Community pharmacists had a good general understanding of most areas relating to topical corticosteroids and adjunct therapy in atopic eczema. In addition, they mostly agreed with statements about what patients should know/understand in line with current advice about the treatment of atopic eczema and indicated that they counselled patients about these during their practice. However they were less likely to provide patient counselling on the safety of topical corticosteroids, possibly due to their own lack of knowledge in this area. Less than 50% of the pharmacists correctly answered questions relating to skin thinning and use of topical corticosteroids in young children. This could be explained by the facts that less than 40% of the pharmacists in the current study had undertaken additional/postgraduate training in dermatological treatment and the majority of those who had, had carried out the training over 7 years ago. This number is lower than another UK study carried out by Tucker [

16] where 65% had undertaken training; CPPE) training packages were reported to be the most commonly used sources with about 50% in both studies.

Community pharmacists play a vital role in educating patients in the use of topical corticosteroids [

15]. However, it is important that pharmacists themselves have the correct understanding before they pass on advice and knowledge to patients and carers. Research has shown that misleading information provided by pharmacists leads to a major impact on the perceptions of topical corticosteroids in the general public [

26]. Charman et al. [

12] found that 73% of patients or carers worried about using topical corticosteroids on their own or their child’s skin and 30% were unable to correctly classify the most commonly used topical corticosteroids. In the current study, over 60% of pharmacists had incorrect knowledge on the number of potency categories in existence and 75% believed that it is not important for the patients to know the potency of their topical corticosteroid. Also, only 44% understood that side effects are uncommon when topical corticosteroids are used appropriately and, interestingly, a similar result (44%) was reported in a study carried out in Australia reporting baseline pharmacist knowledge, which was significantly increased post-education to 89% [

27].

Although the BNF, a drug formulary that all UK pharmacists refer to, has clearly indicated that ‘treatment should not necessarily be reserved to treat only the worst areas’, only 23% of the respondents in this study had the correct knowledge on this, which could explain why only 22% reported they would provide such advice routinely; yet more than half (54%) actually believed that it is important for patients or carers to know this same information. This suggests that increasing pharmacist knowledge or empowering them in other ways could potentially increase the provision of counselling in this area. This is also true in term of pharmacists’ knowledge about topical corticosteroid potency; 63% did not know the potency grading, but 75% believed it is still important for the patient to know, and despite this, 73% would routinely provide advice on topical corticosteroid potency. This raises the question that if the pharmacists themselves do not have the correct knowledge, they could misinform patients and lead to topical corticosteroid phobia. Our study has highlighted the need for evidence-based health literacy education for pharmacists in order to avoid patient misunderstanding of topical corticosteroids. A study in Australia on topical corticosteroid phobia also highlighted this issue [

26].

In the UK, General Pharmaceutical Council standards for pharmacy professionals stipulate that all pharmacists should provide patient-centred care [

28]. However, our study indicates that while community pharmacists believe they have a role in providing advice on topical corticosteroid use as well as non-drug management of atopic eczema, they expressed that medication counselling is difficult due to patients often being unable to speak to a pharmacist. For example, one participant stated: “

So it is up to us (the pharmacists) to pass on the message. But it depends if they get to speak to the pharmacist or not.” Some felt a dilemma when selling OTC topical corticosteroid products especially when another healthcare professional suggests that the patient should buy a product not licensed for the particular indication. For example, one participant said: “

GPs telling people to buy topical steroid that I am not supposed to sell them for. Or nurses as well telling them to go to the pharmacy to buy it to put on your face. Or my child is 7 and the doctor told me to come and buy this. Cause they could make it very difficult for us”.

Pharmacists in this study stated that they would frequently counsel the patient on the quantity of topical corticosteroid to be applied but a third did not use the finger-tip unit as a guide. This finding is also in-line with the interview findings, where only one out of the five interviewees used the finger-tip unit in their counselling, whereas other pharmacists articulated ambiguous or confusing advice on the amount to be used (

Table 2). For topical corticosteroid formulations, fewer pharmacists believed this area is important for the patients to know and this was reflected in the section on self-reported counselling behaviours. In terms of topical corticosteroid safety and effectiveness, although nearly all the pharmacists had a positive attitude, they did not routinely provide counselling on this topic. This could be due to lack of opportunity to discuss this topic in a consultation. Due to time constraints, pharmacists may prefer to counsel patients or carers on application of topical corticosteroids and use of emollients than specifically on topical corticosteroid safety. Points regarding time and counselling opportunity also came out from the interviews; for example, one participant stated: “

by giving an MUR have more time. Usually be able to find out how they use their cream”. Potentially, if time is not the limiting factor, i.e., pharmacist time could be freed up for counselling, then improving pharmacists’ attitudes towards information provision could potentially improve counselling behaviour on the use of topical corticosteroids in the treatment of atopic eczema, as generally there is a positive association between the two concepts.

The strengths of this study are that we have used the mixed-method approach in which the second phase of the study was partly developed from the first. The qualitative study helped us to generate themes to be tested in the questionnaire, but vice versa, findings from the questionnaires could also be explained through insights obtained from the interviews. Also, the study obtained responses anonymously with pharmacists representing different age groups, years in practice and both genders completing and returning the questionnaire. We acknowledge that this study does have some limitations. The fact that we only used one medium-sized pharmacy chain for the distribution of the questionnaire and given the relatively small sample and response rate, mainly from pharmacy managers, restricts the generalisability of these findings to the wider community pharmacy population. Also, we cannot be sure that participants did not take time out to research answers for the knowledge section and cannot prevent the inherent biases in self-reporting of behaviours in questionnaires (rather than actually measuring behaviours).