Post-Monolingual Research Methodology: Multilingual Researchers Democratizing Theorizing and Doctoral Education

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- make original contributions to theoretical knowledge by using concepts, metaphors, images and modes of critical thinking from their full linguistic repertoire, and

- deal with the tensions created by English-only monolingual theory, research and education, including rigidities associated with just using English and theories available in English.

1.1. Current Research Informing Post-Monolingual Research Methodology

1.2. Aim and Main Conclusions

2. A Longitudinal Multi-Cohort Study: Collaborative Monolingual/Multilingual Research Methods

- The potential of post-monolingual research methodology across this time with changing cohorts of multilingual HDRs;

- The changes that the post-monolingual research methodology produced in the multilingual HDRs’ capabilities and willingness to use their complete linguistic repertoire to theorize, and

- The changes warranted in this post-monolingual research methodology itself as a result of multilingual HDRs’ demonstrated capabilities for theorizing.

- using HDRs’ multilingual capabilities to make original contributions to knowledge;

- using funds of theoretical knowledge in Zhongwen for research;

- multilingual HDRs’ intellectual agency in Anglophone teacher education;

- pedagogies for the transnational, reciprocal exchange of higher order knowledge;

- using teachers’ technological, pedagogical and content knowledge for cross-sociolinguistic language education, and

- sociocultural literacy learning for young children.

- democratizing research education conducted in the English language;

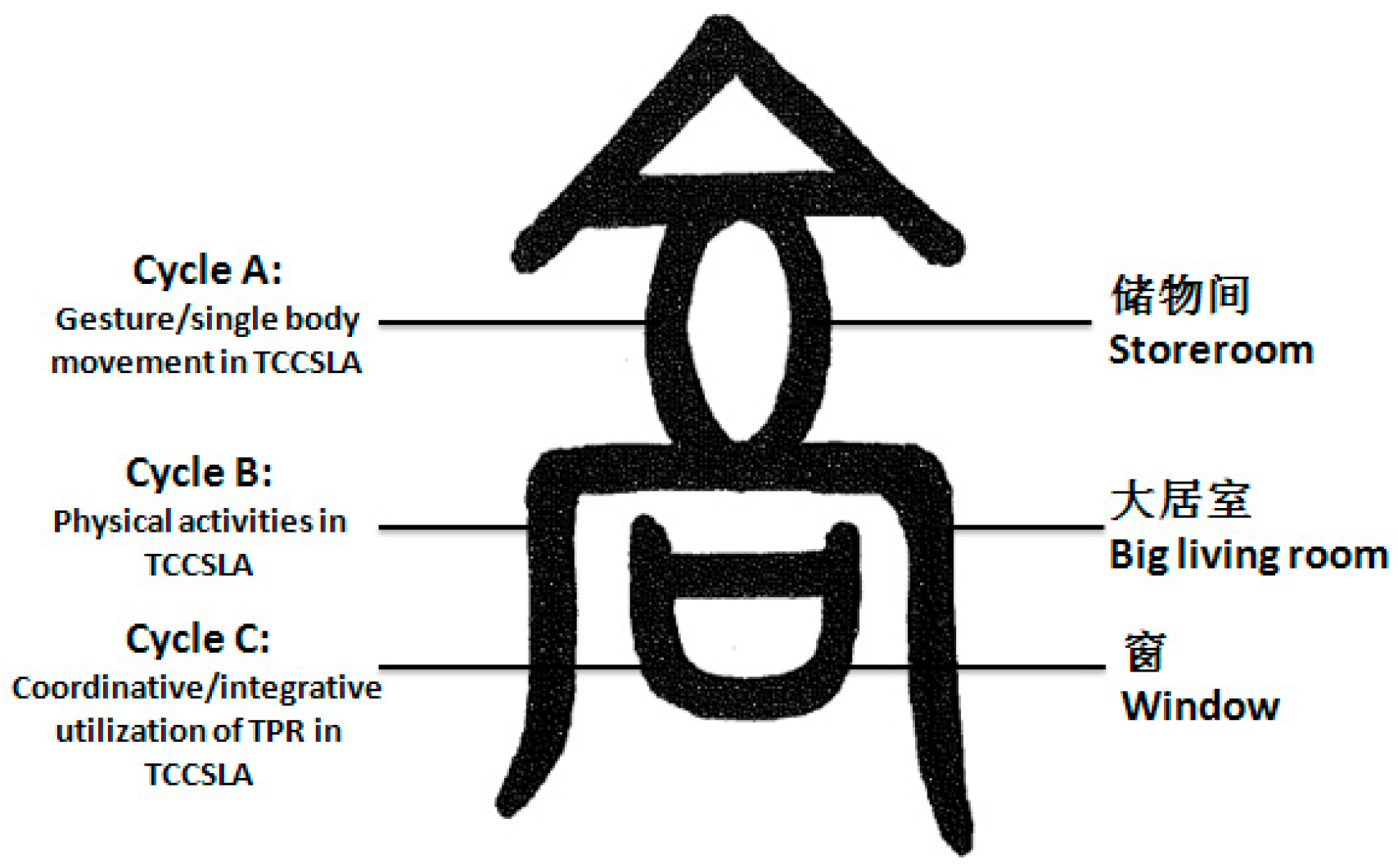

- embodying the teaching/learning of Zhongwen;

- an Australian/Chilean professional development program for early childhood educators, and

- modes of critical thinking in Zhongwen.

3. Results: Multilingual HDRs Developing Their Capabilities for Theorizing

- situating the use of metaphors, images, concepts and critical thinking as theoretical tools in reference to relevant literature;

- bringing forward, defining and constituting metaphors, images, concepts and modes of critique from Zhongwen as theoretic-linguistic tools, and

- using these theoretic-linguistic tools in a non-linear, iterative way to make meaningful analyses or interpretations of empirical observations or research processes.

3.1. Metaphors

3.2. Images

3.3. Concepts

3.4. Modes of Critical Thinking

4. Discussion: Theorising through Intercultural Divergences within/between Language

5. Conclusions

- intellectual merit of multilingual HDRs who understand more about theory and theorizing, and the contribution that their languages and intellectual cultures can make in this regard;

- the importance for universities of adding value to multilingual HDRs’ languages, for instance through them generating theoretic-linguistic resources;

- significance of constructing theoretic-linguistic dialogues among intellectual cultures to advance innovations in knowledge production;

- the importance of countering the press for standardization through English-only monolingualism and uniformity through privileging Anglo-American theoretical knowledge.

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| English | |

|---|---|

| Northern European Languages | |

| Afrikaans | |

| Celtic | |

| Danish | |

| Dutch | |

| Dutch and Related Languages | |

| Estonian | |

| Finnish | |

| German | |

| German and Related Languages | |

| Northern European | |

| Norwegian | |

| Swedish | |

| languages with fewer than 20 students | |

| Southern European Languages | |

| French | |

| Greek | |

| Italian | |

| Maltese | |

| Portuguese | |

| Spanish | |

| languages with fewer than 20 students | |

| Eastern European Languages | |

| Albanian | |

| Armenian | |

| Bosnian | |

| Bulgarian | |

| Croatian | |

| Czech | |

| Hungarian | |

| Latvian | |

| Lithuanian | |

| Macedonian | |

| Polish | |

| Romanian | |

| Russian | |

| Serbian | |

| Serbo-Croatian/Yugoslavian, so described | |

| Slovak | |

| Slovene | |

| Ukrainian | |

| languages with fewer than 20 students | |

| Southwest and Central Asian Languages | |

| Amharic | |

| Arabic | |

| Armenian | |

| Assyrian Neo-Aramaic | |

| Chaldean Neo-Aramaic | |

| Dari | |

| Hazaraghi | |

| Hebrew | |

| Iranic | |

| Kurdish | |

| Middle Eastern Semitic Languages | |

| Pashto | |

| Persian | |

| Persian (excluding Dari) | |

| Tigrinya | |

| Turkic | |

| Turkish | |

| Turkmen | |

| Uygur | |

| languages with fewer than 20 students | |

| Southern Asian Languages | |

| Bengali | |

| Fijian Hindustani | |

| Gujarati | |

| Hindi | |

| Indo-Aryan | |

| Kannada | |

| Konkani | |

| Malayalam | |

| Marathi | |

| Nepali | |

| Other Southern Asian Languages | |

| Punjabi | |

| Sindhi | |

| Sinhalese | |

| Southern Asian Languages | |

| Tamil | |

| Telugu | |

| Urdu | |

| languages with fewer than 20 students | |

| Southeast Asian Languages | |

| Bisaya | |

| Burmese | |

| Burmese and Related Languages | |

| Cebuano | |

| Filipino | |

| Haka | |

| Hmong | |

| Hmong-Mien | |

| Ilonggo (Hiligaynon) | |

| Indonesian | |

| Karen | |

| Khmer | |

| Lao | |

| Malay | |

| Other Southeast Asian Languages | |

| Tagalog | |

| Tagalog (Filipino) | |

| Tetum | |

| Thai | |

| Vietnamese | |

| languages with fewer than 20 students | |

| Eastern Asian Languages | |

| Cantonese | |

| Chinese | |

| Hakka | |

| Japanese | |

| Korean | |

| Mandarin | |

| Min Nan | |

| Mongolian | |

| Other Eastern Asian Languages | |

| Tibetan | |

| Wu | |

| languages with fewer than 20 students | |

| Australian Indigenous Languages | |

| Aboriginal English, so described | |

| Australian Indigenous Languages | |

| languages with fewer than 20 students | |

| Other Languages | |

| Acholi | |

| African Languages | |

| Afrikaans | |

| Akan | |

| American Languages | |

| Amharic | |

| Auslan | |

| Bari | |

| Bemba | |

| Dinka | |

| Fijian | |

| Harari | |

| Igbo | |

| Kinyarwanda (Rwanda) | |

| Kirundi (Rundi) | |

| Krio | |

| Luganda | |

| Madi | |

| Maori (New Zealand) | |

| Mauritian Creole | |

| Ndebele | |

| Nuer | |

| Oceanian Pidgins and Creoles | |

| Oromo | |

| Other Languages | |

| Papua New Guinea Languages | |

| Papuan Languages | |

| Samoan | |

| Shona | |

| Somali | |

| Swahili | |

| Tigrinya | |

| Tok Pisin (Neomelanesian) | |

| Tongan | |

| Yoruba | |

| Zulu | |

| languages with fewer than 20 students | |

References

- Singh, M. Worldly critical theorizing in Euro-American centered teacher education? In Global Teacher Education; Zhu, X., Zeichner, K., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 141–169. [Google Scholar]

- McGagh, J.; Marsh, H.; Western, M.; Thomas, P.; Hastings, A.; Mihailova, M.; Wenham, M. Review of Australia’s Research Training System; Australian Council of Learned Academies: Melbourne, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Illich, I. Shadow Work; Maple-Vail: York, PA, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, M. Connecting intellectual projects in China and Australia: Bradley’s international student-migrants, Bourdieu and productive ignorance. Aust. J. Educ. 2010, 54, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makarychev, A.; Morozov, V. Is “non-Western theory” possible? Int. Stud. Rev. 2013, 15, 328–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Government Department of Education and Training, Ethnicity Related Data. Available online: https://docs.education.gov.au/node/41736 (accessed on 15 September 2016).

- Gurlitt, J.; Renkl, A. Are high-coherent concept maps better for prior knowledge activation? Differential effects of concept mapping tasks on high school vs. university students. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2008, 24, 407–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- House, J. English as a global lingua franca. Lang. Teach. 2014, 47, 363–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M. Using Chinese knowledge in internationalising research education: Jacques Rancière, an ignorant supervisor and doctoral students from China. Glob. Soc. Educ. 2009, 7, 185–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balfour, R. University language policies, internationalism, multilingualism, and language development in South Africa and the UK. Camb. J. Educ. 2007, 37, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choy, S.; Li, M.; Singh, P. The Australian doctorate curriculum. Int. J. Res. Dev. 2015, 6, 165–182. [Google Scholar]

- Said, E. Out of Place: A Memoir; Granta Books: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Gogolin, I. The ‘monolingual habitus’ as the common feature in teaching in the language of the majority in different countries. Per Linguam 1997, 13, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doiz, A.; Lasagabaster, D.; Sierra, J. What does ‘international university’ mean at a European bilingual university? The role of languages and culture. Lang. Aware. 2014, 23, 172–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordin, M. Scientific Babel; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Takayama, K. Deploying the post-colonial predicaments of researching on/with ‘Asia’ in education. Discourse 2016, 37, 70–88. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, J. Teaching and learning for international students. Teach. Teach. 2011, 17, 631–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M. Pedagogies of intellectual equality for connecting with non-Western theories. In Precarious International Multicultural Education; Wright, H., Singh, M., Race, R., Eds.; Sense: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 237–258. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, M.; Manathunga, C.; Bunda, T.; Qi, J. Mobilising Indigenous and non-Western theoretic-linguistic knowledge in doctoral education. Knowl. Cult. 2016, 4, 54–68. [Google Scholar]

- Clegg, S. On the problem of theorising. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2012, 31, 407–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marker, M. Theories and disciplines as sites of struggle. Can. J. Nativ. Educ. 2004, 28, 102–110. [Google Scholar]

- Biesta, G.; Allan, J.; Edwards, R. The theory question in research capacity building in education. Br. J. Educ. Stud. 2011, 59, 225–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markovsky, B. Graduate training in sociological theory and theory construction. Sociol. Perspect. 2008, 51, 423–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weick, K. What theory is not, theorizing is. Adm. Sci. Q. 1995, 40, 385–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swedberg, R. On Charles’ Peirce’s lecture “how to theorize.”. Sociologica 2012, 2, 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Sutton, R.; Staw, B. What theory is not. Adm. Sci. Q. 1995, 40, 371–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swedberg, R. Before theory comes theorizing or how to make social science more interesting. Br. J. Sociol. 2016, 67, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swedberg, R. Theorizing in sociology and social science. Theory Soc. 2012, 41, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weick, K. Theory construction as disciplined imagination. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 516–531. [Google Scholar]

- Spickard, J. Ethnocentrism, social theory and Non-Western sociologies of religion toward a Confucian alternative. Int. Sociol. 1989, 13, 173–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudestam, K.; Newton, R. Surviving Your Dissertation: A Comprehensive Guide to Content and Process; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery, S. Science in Translation; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Levitt, R.; Janta, B.; Shehabi, A.; Jones, D.; Valentini, E. The Supply of and Demand for UK Born and Educated Academic Researchers with Skills in Languages Other Than English; (Technical Report); RAND Corporation: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hamel, R. Engaging a plurilingual scientific community: Multiple languages for international academic publications. Anthropol. News. 2010, 51, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, R.; Muller, J. The discourse of ‘voice’ and the problem of knowledge and identity in the sociology of education. Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 1999, 20, 189–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, M. Education, globalisation and the ‘voice of knowledge’. J. Educ. Work 2009, 22, 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, R. Acceptable and unacceptable immigrants: How opposition to immigration in Britain is affected by migrants’ region of origin. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2011, 37, 1017–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J. Multilingualism: Understanding Linguistic Diversity; Bloomsbury: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ndhlovu, F. A decolonial critique of diaspora identity theories and the notion of superdiversity. Diaspora Stud. 2016, 9, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, N.; Lewis, M. From truncated to sociopolitical emergence: A critique of super-diversity in sociolinguistics. Int. J. Sociol. Lang. 2016, 241, 97–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piller, I. Monolingual ways of seeing multilingualism. J. Multicult. Discourses 2016, 11, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M. Urban education across the post-colonial, post-cold War South Pacific: Changes in the trans-national order of theorizing. In Second International Handbook of Urban Education; Pink, W., Noblit, G., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, M.; Cui, G. Internationalising Western doctoral education through bilingual research literacy. Pertan. J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2011, 19, 535–545. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, M.; Qi, J. The educational travels of Tibetan knowledge. In Indigenous People; Craven, R., Bodkin-Andrews, G., Mooney, J., Eds.; Information Age Publishing: Charlotte, NC, USA, 2013; pp. 123–148. [Google Scholar]

- Jullien, F. On the Universal, the Uninform, the Common and Dialogue between Cultures; Polity Press: Cambridge: UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, M.; Fu, D. Flowery inductive rhetoric meets creative deductive arguments. Int. J. Asia Pac. Stud. 2008, 4, 121–137. [Google Scholar]

- Parr, N. Who goes to university? The changing profile of our students. The Conversation, 25 May 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, M.; Fu, D. Are we uncritical, unfocussed, plagiarising rote learners? In Changing University Learning and Teaching; McConachie, J., Ed.; PostEd Press: Teneriffe, Autralia, 2008; pp. 261–280. [Google Scholar]

- Schneiderhan, E. Theorizing resistance. Br. J. Sociol. 2016, 67, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kvale, S.; Brinkman, S. Interviews; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, L.; Nguyen, N. Re-imagining teachers’ identity and professionalism under the condition of international education. Teach. Teach. 2015, 21, 958–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, D. Threatening Anthropology; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Rancière, J. The Ignorant Schoolmaster; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Hilliard, C. To Exercise Our Talents; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, M.; Harreveld, R.; Chen, C. The presupposition of equality of theoretical assets from diverse educational cultures. In Cultural and Social Diversity and the Transition from Education to Work; Tchibozo, G., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Nethrlands, 2012; pp. 75–94. [Google Scholar]

- Jullien, F. The Book of Beginning; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, M. Translating Studies of Asia: A Curriculum Statement for Negotiation in Australian Schools; Australian Curriculum Studies Association: Canberra, Australia, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, M.; Huang, X. Declassifying Sino-Anglo divisions over critical theorising. Compare 2013, 43, 549–566. [Google Scholar]

- Nie, J.; Gilbertson, A.; de Roubaix, M.; Staunton, C.; van Niekerk, A.; Tucker, J.; Rennie, S. Healing without waging war: Beyond military metaphors in medicine and HIV cure research. American J. Bioeth. 2016, 16, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakoff, G.; Johnson, M. Metaphors We Live By; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, H. Democratising English Language Research Education in the Face of Eurocentric Knowledge Transfer. Ph.D. Thesis, Western Sydney University, Penrith, Australia, 20 January 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rancière, J. Hatred of Democracy; Verso: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Phadi, M.; Manda, O. The language of class: Southern Sotho and Zulu meanings of ‘middle class’ in Soweto. S. Afr. Rev. Sociol. 2010, 41, 81–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shteir, A.; Lightman, B. (Eds.) Figuring It Out: Science, Gender and Visual Culture; Dartmouth College: Hanover, UK, 2006.

- Swedberg, R. Can you visualize theory? Sociol. Theory 2016, 34, 250–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, T. Shake Your Amazing Body. Master of Education Honours research Thesis, Western Sydney University, Penrith, Australia, 31 March 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kigamwa, J.; Ndemanu, M. Translingual practice among African immigrants in the US. J. Multiling. Multicult Dev. 2016, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carleheden, M. What conception of the theoretical does ‘theorizing’ presuppose? Br. J. Sociol. 2016, 67, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, J. Multilingual Critique in Transnational Education. Ph.D. Thesis, Western Sydney University, Penrith, Australia, 30 August 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Alatas, F. Alternative Discourses in Asian Social Science; Sage: New Delhi, India, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, M. Learning from China to internationalise Australian research education: Pedagogies of intellectual equality and ‘optimal ignorance’ of ERA journal rankings. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 2011, 48, 395–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egege, S.; Kutieleh, S. Critical thinking: Teaching foreign notions to foreign students. Int. Educ. J. 2004, 4, 75–85. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, S. Chinese Modes of Critical Thinking. Ph.D. Thesis, Western Sydney University, Penrith, Australia, 30 August 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Snowden, A. Ethics and originality in doctoral research in the UK. Nurse Res. 2014, 21, 12–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, G. Worrying about China: The Language of Chinese Critical Inquiry; Harvard University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Rutar, S. Multilingual learning and teaching as a principle of inclusive practice. Sodob. Pedagog. 2014, 65, 10–25. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, H. Matters of Exchange; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Macedo, D.; Dendrinos, B.; Gounari, P. Hegemony of English; Routledge, New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, D.; Wynyard, R. (Eds.) The McDonaldization of Higher Education; Information Age Publishing: Charlotte, NC, USA, 2006.

| Concept | Word for Word Translation | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| 教学做合一 | “教” means teaching; “学” means learning; “做” means doing, and “合一” means to combine, to unite. | teaching, doing and learning is one combined process and not three separate processes |

| 循序渐进 | 循xún means ‘in accordance’, 序xù means ‘order’, 渐jiàn means ‘gradually’, 进jìn means ‘progress or improve’ | making progress and improvements in study/work at a reasonable pace |

| Hanzi | Pinyin | English Translation |

|---|---|---|

| 因材施教, 因财施教 | yin cai shi jiao, yin cai shi jiao | teaching according to aptitude (versus) teaching according to money |

| 生如夏花,却被折下 | shēng rú xiahuā, què bei zhéxià | life is as summer flowers, but it is snapped off |

| 温故而知新 | wēn gù er zhī xīn | Getting to the unknown through the known. |

© 2017 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Singh, M. Post-Monolingual Research Methodology: Multilingual Researchers Democratizing Theorizing and Doctoral Education. Educ. Sci. 2017, 7, 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci7010028

Singh M. Post-Monolingual Research Methodology: Multilingual Researchers Democratizing Theorizing and Doctoral Education. Education Sciences. 2017; 7(1):28. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci7010028

Chicago/Turabian StyleSingh, Michael. 2017. "Post-Monolingual Research Methodology: Multilingual Researchers Democratizing Theorizing and Doctoral Education" Education Sciences 7, no. 1: 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci7010028