Research Foundations for Evidence-Informed Early Childhood Intervention Performance Checklists

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Background

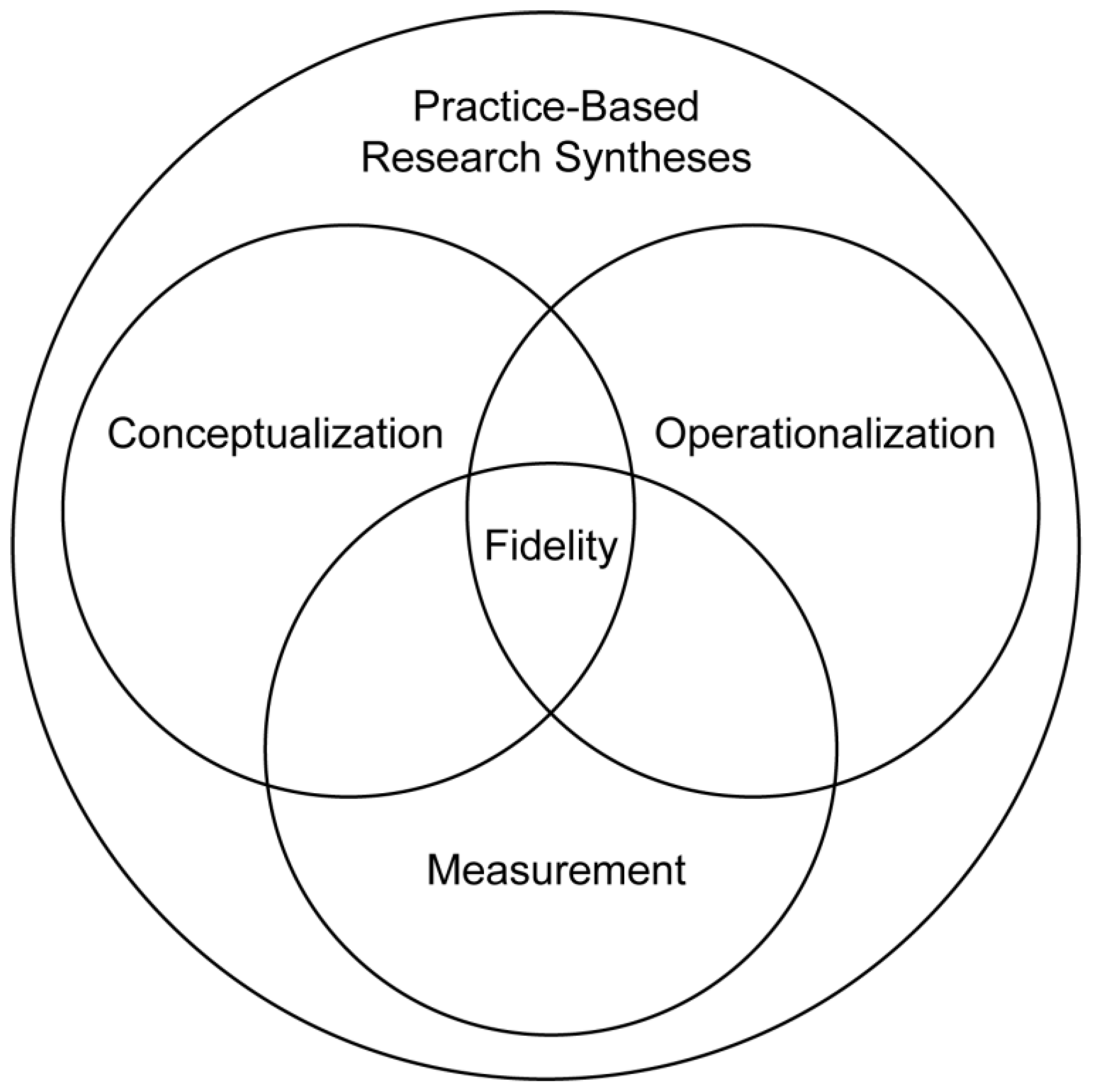

1.2. Procedure for Developing Evidence-Informed Performance Checklists

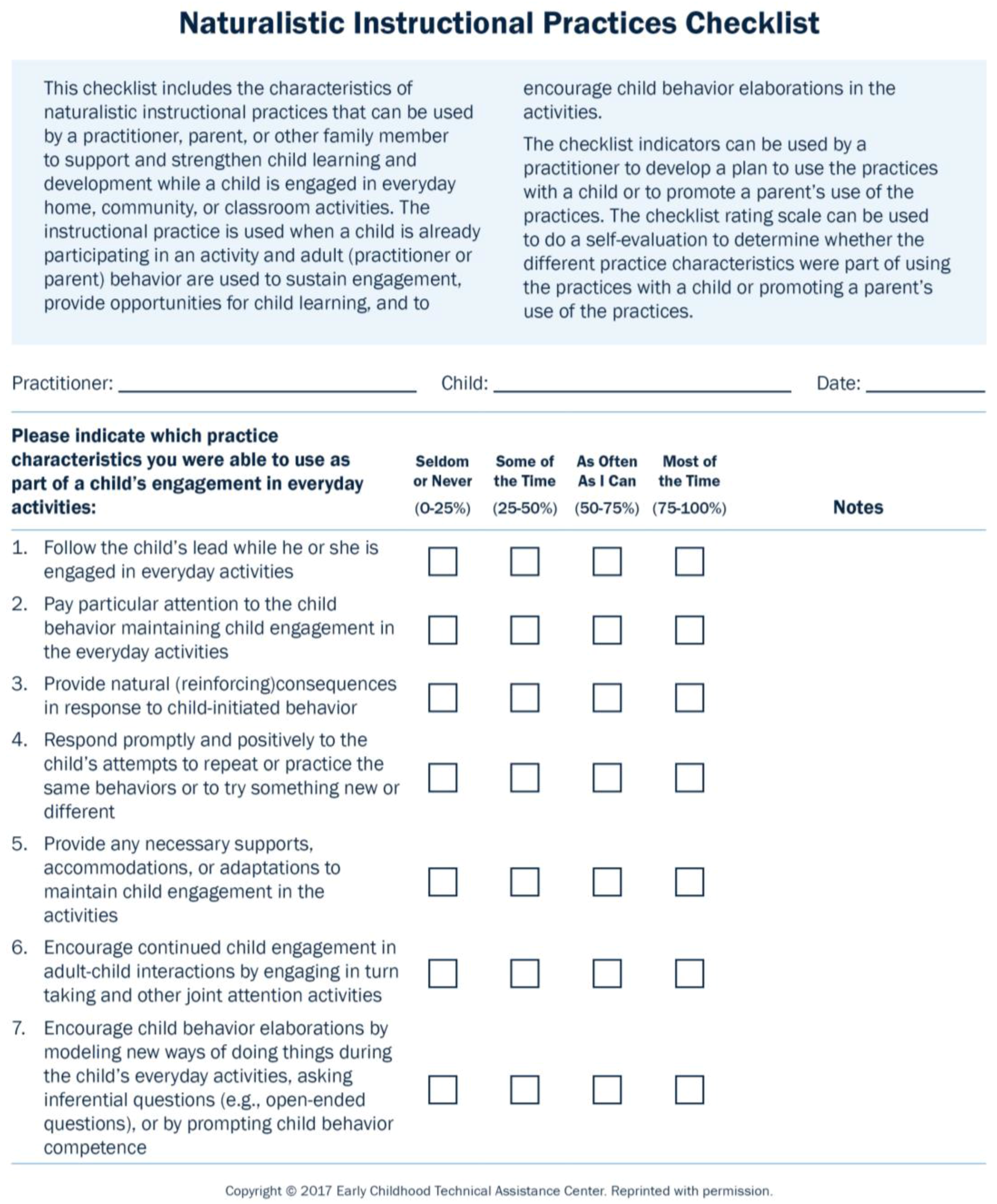

The practices on each checklist (e.g., naturalistic instruction) are conceptualized as a particular type of early childhood intervention practice; for example, [21]. The evidence for the checklist indicators was used to operationalize the key characteristics of the practice (e.g., following a child’s lead, sensitivity to child behavioral cues, responding promptly and positively to child behavior, and providing natural consequences to reinforce child behavior initiations as indicators of naturalistic instruction); for example, Dunst et al. [22] (p. 5). Figure 2 (p. 4) illustrates the checklist formatting for the Naturalistic Instructional Practices Checklist. The checklist includes seven key characteristics of this particular teaching strategy. The checklist also includes a description of the purpose of the practice, where and how the practice is used to facilitate and reinforce child learning, and guidelines for using the checklist to plan interventions (Read-do) and evaluate how well the practice was used with a child (Do-confirm) [4]. All of the performance checklists are formatted in an identical manner.

1.3. Evidence-Informed Performance Checklists

1.3.1. Assessment Practices Checklists

1.3.2. Environmental Practices Checklists

1.3.3. Family-Focused Practices Checklists

1.3.4. Instructional Practices Checklists

1.3.5. Interactional Practices Checklists

1.3.6. Teaming and Collaboration Practices Checklists

1.3.7. Transition Practices Checklists

2. Methodological Approach

2.1. Sources of Research Evidence

2.2. Types of Research Evidence

2.3. Focus of the Meta-Review

2.4. Scope of Evidence

2.5. Caveats

3. Findings

3.1. Assessment Practices

3.1.1. Authentic Child Assessment Practices

3.1.2. Child Strengths-Based Practices

3.1.3. Informed Clinical Opinion Practices

3.1.4. Engaging Families as Partner Practices

3.2. Environmental Practices

3.2.1. Assistive Technology Practices

3.2.2. Environmental Adaptation Practices

3.2.3. Natural Learning Opportunity Practices

3.2.4. Physical Activity Practices

3.3. Family-Focused Practices

3.3.1. Family-Centered Practices

3.3.2. Family Decision-Making and Engagement Practices

3.3.3. Family Capacity-Building Practices

3.4. Instructional Practices

3.5. Interactional Practices

3.6. Teaming Practices

3.6.1. Team Communication and Collaboration Practices

3.6.2. Family Involvement Practices

3.7. Transition Practices

4. Discussion and Conclusions

4.1. Summary of the Findings

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

4.3. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Type of Evidence | Checklist a | Sources of Evidence | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ES | 4 | Bagnato, S. J. (2007). Authentic assessment for early childhood intervention: Best practices. New York, NY: Guilford Press. | |

| RS | 4 | Bagnato, S.J., McKeating-Esterle, E., Fevola, A., Bortolamasi, P., & Neisworth, J.T. (2008). Valid use of clinical judgment (informed opinion) for early intervention eligibility: Evidence base and practice characteristics. Infants & Young Children, 21(4), 334–349, doi:10.1097/01.IYC.0000336545.90744.b0. | |

| RS | 3, 4 | Bagnato, S.J., Smith-Jones, J., Matesa, M., & McKeating-Esterle, E. (2006). Research foundations for using clinical judgment (informed opinion) for early intervention eligibility determination. Cornerstones, 2(3). Retrieved from http://www.puckett.org/Trace/cornerstones/cornerstones_vol2_no3.pdf. | |

| RS | 4 | Bosch, M., Faber, M.J., Cruijsbery, J., Voerman, G.E., Leatherman, S., Grol, R.P.T.M., …, Wensing, M. (2009). Effectiveness of patient care teams and the role of clinical expertise and coordination. Medical Care Research and Review, 66(6_suppl), 5S–35S, doi:10.1177/1077558709343295. | |

| RS | 1, 4 | Bryce, G.Y. (2010). The Use of Authentic Assessment in Eligibility Determination for Early Childhood Intervention Programs. Ann Arbor, MI, USA: ProQuest. | |

| RS | 1, 2 | Bult, M.K., Verschuren, O., Jongmans, M.J., Lindeman, E., & Ketelaar, M. (2011). What influences participation in leisure activities of children and youth with physical disabilities? A systematic review. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 32, 1521–1529, doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2011.01.045. | |

| RS | 1, 2 | Bult, M. (2012). Participation in Leisure Activities of Children and Adolescents with Physical Disabilities. Ridderberk, Netherlands: Ridderprint. Retrieved from https://dspace.library.uu.nl/bitstream/1874/255243/1/bult.pdf. | |

| ES | 1 | Chiarello, L.A., Banlett, D.I., Palisano, R.J., McCoy, S.W., Fiss, A.L., Jeffries, L., & Wilk, P. (2016). Determinants of participation in family and recreational activities of young children with cerebral palsy. Disability and Rehabilitation, 28(25), 2455–2468, doi:10.3109/09638288.2016.1138548. | |

| RS | 1, 4 | Coulthard, N. (2009). Service trends and practitioner competencies in early childhood intervention: A review of the literature. Retrieved from https://www.eciavic.org.au/documents/item/26. | |

| RS | 3 | Dunst, C.J. (2002). Family-centered practices: Birth through high school. Journal of Special Education, 36, 139–147, doi:10.1177/00224669020360030401. | |

| ES | 1 | Dunst, C.J., Hamby, D., Trivette, C.M., Raab, M., & Bruder, M.B. (2002). Young children’s participation in everyday family and community activity. Psychological Reports, 91, 875–897, doi:10.2466/PR0.91.7.875–897. | |

| RS | 2 | Dunst, C.J., Jones, T., Johnson, M., Raab, M., & Hamby, D.W. (2011). Role of children’s interests in early literacy and language development. CELLreviews, 4(5), 1–18. Retrieved from http://www.earlyliteracylearning.org/cellreviews/cellreviews_v4_n5.pdf. | |

| RS | 1 | Dunst, C.J., Raab, M., & Trivette, C.M. (2013). Methods for increasing child participation in interest-based language learning activities. Everyday Child Language Learning Tools, Number 4, 1–6. Retrieved from http://www.puckett.org/CECLL/ECLLReport_7_LearnOps.pdf. | |

| RS | 2 | Dunst, C.J., Trivette, C.M., & Hamby, D.W. (2012). Effect of interest-based interventions on the social-communicative behavior of young children with autism spectrum disorders. CELLreviews, 5(6), 1–10. Retrieved from http://www.earlyliteracylearning.org/cellreviews/cellreviews_v5_n6.pdf. | |

| RS | 2 | Dunst, C.J., Trivette, C.M., & Hamby, D.W. (2012). Meta-analysis of studies incorporating the interests of young children with autism spectrum disorders into early intervention practices. Autism Research and Treatment, 2012, 1–10, doi:10.1155/2012/462531. | |

| RS | 4 | Ericsson, K.A., & Charness, N. (1994). Expert performance: Its structure and acquisition. American Psychologist, 49, 725–747. | |

| RS | 4 | Ericsson, K.A., Krampe, R.T., & Tesch-Romer, C. (1993). The role of deliberate practice in the acquisition of expert performance. Psychological Review, 100, 363–406. | |

| RS | 1, 2 | Fiese, B.H., Tomcho, T.J., Douglas, M., Josephs, K., Poltrock, S., & Baker, T. (2002). A review of 50 years of research on naturally occuring family routines and rituals: Cause for celebration? Journal of Family Psychology, 16(4), 381–390, doi:10.1037//0893-3200.16.4.381. | |

| RS | 1, 3, 4 | Finello, K.M. (2011). Collaboration in the assessment and diagnosis of preschoolers: Challenges and opportunities. Psychology in Schools, 48(5), 442–253, doi:10. 1002/pits.20566. | |

| RS | 4 | Guralnick, S., Ludwig, S., & Englander, R. (2014). Domain of competence: Systems-based practice. Academic Pediatrics, 14, S70–S79. Retrieved from https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PDFs/Milestones/Systems-basedPracticePediatrics.pdf doi:10.1016/j.acap.2013.11.015. | |

| ES | 1 | Haney, M., & Cavallaro, C.C. (1996). Using ecological assessment in daily program planning for children with disabilities in typical preschool settings. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 16, 66–81. | |

| RS | 1, 2 | Kern, L., Maher Choutka, C., & Sokol, N.G. (2002). Assessment-based antecedent interventions used in natural settings to reduce challenging behavior: An analysis of the literature. Education and Treatment of Children, 25(1), 113–130. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/42900519. | |

| ES | 1, 2 | Kemp, C., Kishida, Y., Carter, M., & Sweller, N. (2013). The effect of activity type on the engagement and interaction of young children with disabilities in inclusive childcare. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 28, 134–143. | |

| RS | 3 | Knopf, H.T., & Swick, K.J. (2008). Using our understanding of families to strengthen family involvement. Early Childhood Education Journal, 35, 419–427, doi:10.1007/s10643-007-0198-z | |

| RS | 3 | Kyzar, K.B., Turnbull, A.P., Summers, J.A., & Gómez, V.A. (2012). The relationship of family support to family outcomes: A synthesis of key findings from research on severe disability. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 37(1), 31–44, doi:10.2511/027494812800903247. | |

| RS | 1 | Kim, A.-H., Vaughn, S., Elbaum, B., Hughes, M.T., Sloan, C.V.M., & Sridhar, D. (2003). Effects of toys or group composition for children with disabilities: A synthesis. Journal of Early Intervention, 25, 189–205, doi:10.1177/105381510302500304. | |

| ES | 3 | Larsson, M. (2000). Organising habilitation services: Team structures and family participation. Child: Care, Health and Development, 26(6), 501–514, doi:10.1046/j.1365–2214.2000.00169.x. | |

| RS | 1 | Lequia, J., Machalicek, W., & Rispoli, M.J. (2012). Effects of activity schedules on challenging behavior exhibited in children with autism spectrum disorders: A systematic review. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 6, 480–492, doi:10.1016/j.rasd.2011.07.008. | |

| ES | 1 | Lobo, M.A., Paul, D.A., Mackley, A., Maher, J., & Galloway, J.C. (2014). Instability of delay classification and determination of early intervention eligibility in the first two years of life. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 35(1), 117–126, doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2013.10.017. | |

| ES | 1, 2 | Mårtensson, F., Boldemann, C., Söderström, M., Blennow, M., Englund, J.-E., & Grahn, P. (2009). Outdoor environmental assessment of attention promoting settings for preschool children. Health and Place, 15, 1149–1157, doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2009.07.002. | |

| ES | 1 | Mihaylov, S.I., Jarvis, S.N., Colver, A.F., & Beresford, B. (2004). Identification and description of environmental factors that influence participation of children with cerebral palsy. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 46, 299–304. | |

| RS | 1 | Morgan, C., Novak, I., & Badawi, N. (2013). Enriched environments and motor outcomes in cerebral palsy: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatrics, 132(3), e735–e746, doi:10.1542/peds.2012-3985. | |

| RS | 1, 4 | Moore, T.G. (2008). Early Childhood Intervention: Core Knowledge and Skills. CCCH Working Paper 3. Parkville, Victoria, Australia: Centre for Community Child Health. | |

| ES | 4 | Mott, D.W., & Dunst, C.J. (2006). Use of presumptive eligibility for enrolling children in Part C early intervention. Journal of Early Intervention, 29, 22–31, doi:10.1177/105381510602900102. | |

| RS | 3 | Nash, J.K. (1990). Public Law 99-457: Facilitating family participation on the multidisciplinary team. Journal of Early Intervention, 14(4), 318–326, doi:10.1177/105381519001400403. | |

| RS | 3 | Nijhuis, B.J.G., Reinders-Messelink, H.A., de Blécourt, A.C.E., Olijve, C.V.G., Groothoff, J.W., Nakken, H., & Postema, K. (2007). A review of salient elements defining team collaboration in paediatric rehabilitation. Clinical Rehabilitation, 21(3), 195–211, doi:10.1177/0269215506070674. | |

| RS | 1 | Odom, S.L., Vitztum, J., Wolery, R., Lieber, J., Sandall, S., Hanson, M.J., …, Horn, E. (2004). Preschool inclusion in the United States: A review of research from an ecological systems perspective. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 4, 17–49, doi:10.1111/J.1471-3802.2004.00016.x. | |

| RS | 1 | Palisano, R.J., Chiarello, L.A., King, G.A., Novak, I., Stoner, T., & Fiss, A. (2012). Participation-based therapy for children with physical disabilities. Disability and Rehabilitation, 34, 1041–1052, doi:10.3109/09638288.2011.628740. | |

| RS | 1, 2 | Petrenchik, T.M., & King, G.A. (2011). Pathways to positive development: Childhood participation in everyday places and activities. In S. Bazyk (Ed.), Mental Health Promotion, Prevention, and Intervention with Children and Youth: A Guiding Framework for Occupational Therapy (pp. 71–94). Bethesda, MD: AOTA Press. | |

| RS | 2 | Raab, M., & Dunst, C.J. (2007). Influence of Child Interests on Variations in Child Behavior and Functioning. Asheville, NC, USA: Winterberry Press. | |

| RS | 2 | Raab, M., Dunst, C.J., & Hamby, D.W. (2013). Relationships between young children’s interests and early language learning. Everyday Child Language Learning Reports, Number 5, 1–14. Retrieved from http://www.cecll.org/download/ECLLReport_5_Interests.pdf. | |

| ES | 1 | Rosenberg, L., Bart, O., Ratzon, N.Z., & Jarus, T. (2013). Personal and environmental factors predict participation of children with and without mild developmental disabilities. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 22(5), 658–671, doi:10.1007/s10826-012-9619-8. | |

| ES | 1, 4 | Shernoff, E.S., Hill, C., Danis, B., Leventhal, B.L., & Wakschlag, L.S. (2014). Integrative consensus: A systematic approach to integrating comprehensive assessment data for young children with behavior problems. Infants & Young Children, 27(2), 92–110, doi:10.1097/IYC.0000000000000008. | |

| RS | 1 | Spagnola, M., & Fiese, B.H. (2007). Family routines and rituals: A context for development in the lives of young children. Infants and Young Children, 20(4), 284–299, doi:10.1097/01.IYC.0000290352.32170.5a. | |

| ES | 3 | Strauss, K., Benvenuto, A., Battan, B., Siracusano, M., Terribili, M., Curatolo, P., & Fava, L. (2015). Promoting shared decision making to strengthen outcome of young children with autism spectrum disorders: The role of staff competence. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 38, 48–63, doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2014.11.016. | |

| RS | 1 | Trivette, C.M., Dunst, C.J., Simkus, A., & Hamby, D.W. (2013). Methods for increasing child participation in everyday learning opportunities. Everyday Child Language Learning Reports, Number 7, 1–7. Retrieved from http://www.cecll.org/download/ECLLReport_7_LearnOps.pdf. | |

| RS | 1 | Van keer, I., & Maes, B. (2016). Contextual factors influencing the developmental characteristics of young children with severe to profound intellectual disability: A critical review. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 1–19, doi:10.3109/13668250.2016.1252458. | |

| RS | 1 | Wachs, T.D. (1999). Celebrating complexity: Conceptualization and assessment of the environment. In S.L. Friedman & T.D. Wachs (Eds.), Measuring environment across the life span: Emerging methods and concepts (pp. 357–392). Washington, DC, USA: American Psychological Association. | |

| RS | 1 | Wachs, T.D. (2000). Necessary but not Sufficient: The Respective Roles of Single and Multiple Influences on Individual Development. Washington, DC, USA: American Psychological Association. | |

| RS | 1, 2 | Weisner, T.S. (2002). Ecocultural understanding of children’s developmental pathways. Human Development, 45, 275–281, doi:10.1177/1529100615569721. | |

Appendix B

| Type of Evidence | Checklist a | Sources of Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| RS | 2 | Ahn, S., & Fedewa, A.L. (2011). A meta-analysis of the relationship between children’s physical activity and mental health. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, doi:10.1093/jpepsy/jsq107. |

| RS | 1 | Alper, S., & Raharinirina, S. (2006). Assistive technology for individuals with disabilities: A review and synthesis of the literature. Journal of Special Education Technology, 21(2), 47–64, doi:10.1080/10400435.2012.723298. |

| RS | 1 | Billington, C. (2016). How Digital Technology can Support Early Language and Literacy Outcomes in Early Years Settings: A Review of the Literature Retrieved from http://www.literacytrust.org.uk/assets/0003/3409/How_digital_technology_can_support_early_language_and_literacy_outcomes_in_early_years_settings.pdf. |

| ES | 4 | Boldemann, C., Blennow, M., Dal, H., Martensson, F., Raustorp, A., Yuen, K., & Wester, U. (2006). Impact of preschool environment upon children’s physical activity and sun exposure. Preventive Medicine, 42, 301–308, doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2005.12.006. |

| ES | 2, 4 | Bower, J.K., Hales, D.P., Tate, D.F., Rubin, D.A., Benjamin, S.E., & Ward, D.S. (2008). The childcare environment and children’s physical activity. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 34(1), 23–29, doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2007.09.022. |

| RS | 1 | Branson, D., & Demchak, M. (2009). The use of augmentative and alternative communication methods with infants and toddlers with disabilities: A research review. AAC: Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 25(4), 274–286, doi:10.3109/07434610903384529. |

| RS | 2, 4 | Brown, H.E., Atkin, A.J., Panter, J., Wong, G., Chinapaw, M.J.M., & van Sluijs, E.M.F. (2016). Family-based interventions to increase physical activity in children: A systematic review, meta-analysis and realist synthesis. Obesity Reviews, 17(4), 345–360, doi:10.1111/obr.12362. |

| RS | 1 | Burnett, C. (2010). Technology and literacy in early childhood educational settings: A review of research. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy, 10, 247–270, doi:10.1177/1468798410372154. |

| RS | 2 | Campbell, K.J., & Hesketh, K.D. (2007). Strategies which aim to positively impact on weight, physical activity, diet and sedentary behaviours in children from zero to five years: A systematic review of the literature. Obesity Reviews, 8, 327–338, doi:10.1111/j.1467-789X.2006.00305.x. |

| RS | 1 | Campbell, P.H., Milbourne, S., Dugan, L.M., & Wilcox, M.J. (2006). A review of evidence on practices for teaching young children to use assistive technology devices. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 26, 3–13, doi:10.1177/02711214060260010101. |

| ES | 3 | Campbell, P.H., Milbourne, S., & Wilcox, M. (2008). Adaptation interventions to promote participation in natural settings. Infants and Young Children, 21(2), 94–106, doi:10.1097/01.IYC.0000314481.16464.75. |

| RS | 1 | Chantry, J., & Dunford, C. (2010). How do computer assistive technologies enhance participation in childhood occupations for children with multiple and complex disabilities? A review of the current literature. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 73, 351–365, doi:10.4276/030802210X12813483277107. |

| ES | 5 | Chiarello, L.A., Banlett, D.I., Palisano, R.J., McCoy, S.W., Fiss, A.L., Jeffries, L., & Wilk, P. (2016). Determinants of participation in family and recreational activities of young children with cerebral palsy. Disability and Rehabilitation, 28(25), 2455–2468, doi:10.3109/09638288.2016.1138548. |

| RS | 4 | Christian, H., Zubrick, S.R., Foster, S., Giles-Corti, B., Bull, F., Wood, L., …, Boruff, B. (2015). The influence of the neighborhood physical environment on early child health and development: A review and call for research. Health & Place, 33, 25–36, doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2015.01.005. |

| RS | 1 | Clarke, B., & Svanaes, S. (2014). Tablets for schools: An updated literature review on the use of tablets in education. London: Family Kids and Youth. Retrieved from http://maneele.drealentejo.pt/site/images/Literature-Review-Use-of-Tablets-in-Education-9-4-14.pdf. |

| RS | 1 | Desideri, L., Roentgen, U., Hoogerwerf, E.-J., & de Witte, L. (2013). Recommending assistive technology (AT) for children with multiple disabilities: A systematic review and qualitative synthesis of models and instruments for AT professionals. Technology and Disability, 25(1), doi:10.3233/TAD-130366. |

| ES | 5 | Dunst, C.J., Bruder, M.B., Trivette, C.M., Hamby, D., Raab, M., & McLean, M. (2001). Characteristics and consequences of everyday natural learning opportunities. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 21, 68–92, doi:10.1177/027112140102100202. |

| ES | 5 | Dunst, C.J., Bruder, M.B., Trivette, C.M., & Hamby, D.W. (2005). Young childre’s natural learning environments: Contrasting approaches to early childhood intervention indicate differential learning opportunities. Psychological Reports, 96, 231–234, doi:10.2466/pr0.96.1.231-234. |

| ES | 5 | Dunst, C.J., Bruder, M.B., Trivette, C.M., & Hamby, D.W. (2006). Everyday activity settings, natural learning environments, and early intervention practices. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 3, 3–10, doi:10.1111/j.1741-1130.2006.00047.x. |

| RS | 1, 3 | Dunst, C.J., & Hamby, D.W. (2015). Research synthesis of studies to promote parent and practitioner use of assistive technology and adaptations with young children with disabilities. In D.L. Edyburn (Ed.), Advances in special education technology (Vol. 1): Efficacy of assistive technology interventions (pp. 51–78). United Kingdom: Emerald Publishing. |

| RS | 5 | Dunst, C.J., Raab, M., & Trivette, C.M. (2013). Methods for increasing child participation in interest-based language learning activities. Everyday Child Language Learning Tools, Number 4, 1–6. Retrieved from http://www.puckett.org/CECLL/ECLLReport_7_LearnOps.pdf. |

| RS | 1 | Dunst, C.J., Trivette, C.M., & Hamby, D.W. (2012). Assistive technology and the communication and literacy development of young children with disabilities. CELLreviews, 5(7), 1–13. Retrieved from http://www.earlyliteracylearning.org/cellreviews/cellreviews_v5_n7.pdf. |

| ES | 5 | Dunst, C.J., Trivette, C.M., Hamby, D.W., & Bruder, M.B. (2006). Influences of contrasting natural learning environment experiences on child, parent, and family well-being. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 18, 235–250, doi:10.1007/s10882-006-9013-9. |

| RS | 1 | Dunst, C.J., Trivette, C.M., Hamby, D.W., & Simkus, A. (2013). Systematic review of studies promoting the use of assistive technology devices by young children with disabilities. Practical Evaluation Reports, 5(1), 1–32. Retrieved from http://www.puckett.org/Practical%20Evaluation%20reports/CPE_Report_Vol5No1.pdf. |

| RS | 5 | Dunst, C.J., Valentine, A., Raab, M., & Hamby, D.W. (2013). Relationship between child participation in everyday activities and early literacy and language development. CELLreviews, 6(1), 1–16. Retrieved from http://www.earlyliteracylearning.org/cellreviews/CELLreviews_v6_n1.pdf. |

| RS | 5 | Fiese, B.H., Tomcho, T.J., Douglas, M., Josephs, K., Poltrock, S., & Baker, T. (2002). A review of 50 years of research on naturally occuring family routines and rituals: Cause for celebration? Journal of Family Psychology, 16(4), 381–390, doi:10.1037//0893-3200.16.4.381. |

| RS | 1 | Floyd, K.K., Canter, L.L.S., Jeffs, T., & Judge, S.A. (2008). Assistive technology and emergent literacy for preschoolers: A literature review. Assistive Technology Outcomes and Benefits, 5, 92–102. |

| RS | 4 | Godbey, G. (2009). Outdoor Recreation, Health, and Wellness: Understanding and Enhancing the Relationship. Washington, DC, USA: Resources for the Future. |

| RS | 2 | Gordon, E.S., Tucker, P., Burke, S.M., & Carron, A.V. (2013). Effectiveness of physical activity interventions for preschoolers: A meta-analysis. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 84, 287–294, doi:10.1080/02701367.2013.813894. |

| ES | 4 | Henderson, K.E., Grode, G.M., O’Connell, M.L., & Schwartz, M.B. (2015). Environmental factors associated with physical activity in childcare centers. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 12, 43, doi:10.1186/s12966-015-0198-0. |

| RS | 2 | Hesketh, K.D., & Campbell, K.J. (2010). Interventions to prevent obesity in 0–5 year olds: An updated systematic review of the literature. Obesity, 18(Suppl. 1), S27–S35. |

| RS | 2, 4 | Hinkley, T., Crawford, D., Salmon, J., Okely, A.D., & Hesketh, K. (2008). Preschool children and physical activity: A review of correlates. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 34, 435–441. |

| RS | 2, 4 | Hinkley, T., Teychenne, M., Downing, K.L., Ball, K., Salmon, J., & Hesketh, K.D. (2014). Early childhood physical activity, sedentary behaviors and psychosocial well-being: A systematic review. Preventive Medicine, 62, 182–192, doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.02.007. |

| RS | 1, 5 | Isabelle, S., Bessey, F., Lawrence-Dragas, K., Blease, P., Shepherd, J., & Lane, S. (2002). Assistive technology for children with disabilities. Occupational Therapy in Health Care, 16(4), 29–51, doi:10.1300/J003v16n04_03. |

| ES | 4 | Jansson, M. (2010). Attractive playgrounds: Some factors affecting user interest and visiting patterns. Landscape Research, 35(1), 63–81, doi:10.1080/01426390903414950. |

| ES | 4, 5 | Kemp, C., Kishida, Y., Carter, M., & Sweller, N. (2013). The effect of activity type on the engagement and interaction of young children with disabilities in inclusive childcare. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 28, 134–143. |

| RS | 2, 4 | Kreichauf, S., Wildgruber, A., Krombholz, H., Gibson, E.L., Vögele, C., Nixon, C.A., …, Summerbell, C.D. (2012). Critical narrative review to identify educational strategies promoting physical activity in preschool. Obesity Reviews, 13(s1), 96–105, doi:10.1111/j.1467-789X.2011.00973.x. |

| RS | 1 | Lauricella, A.R., Blackwell, C.K., & Wartella, E. (2016). The “new” technology environment: The role of content and context on learning and development from mobile media. In R. Barr & D.N. Linebarger (Eds.), Media exposure during infancy and early childhood (pp. 1–23). Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing. |

| RS | 4, 5 | Lequia, J., Machalicek, W., & Rispoli, M.J. (2012). Effects of activity schedules on challenging behavior exhibited in children with autism spectrum disorders: A systematic review. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 6, 480–492, doi:10.1016/j.rasd.2011.07.008. |

| RS | 1 | Light, J., & McNaughton, D. (2012). Supporting the communication, language, and literacy development of children with complex communication needs: State of the science and future research priorities. Assistive Technology, 24(1), 34–44, doi:10.1080/10400435.2011.648717. |

| RS | 1 | Lovato, S., & Waxman, S.R. (2016). Young children learning from touch screens: Taking a wider view. Frontiers in Psychology. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4947576/pdf/fpsyg-07-01078.pdf doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01078. |

| RS | 2, 4 | Mihaylov, S.I., Jarvis, S.N., Colver, A.F., & Beresford, B. (2004). Identification and description of environmental factors that influence participation of children with cerebral palsy. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 46, 299–304. |

| RS | 1 | Millar, D.C., Light, J.C., & Schlosser, R.W. (2006). The impact of augmentative and alternative communication intervention on the speech production of individuals with developmental disabilities: A research review. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 49, 248–264. |

| RS | 1 | Mistrett, S.G., Hale, M.M., Diamond, C.M., Ruedel, K.L.A., Gruner, A., Sunshine, C., …, McInerney, M. (2001). Synthesis on the Use of Assistive Technology with Infants and Toddlers (Birth through Two). Retrieved from Washington, DC, USA: Retrieved from http://www.fctd.info/webboard/files/AIR_EI-AT_Report_2001.pdf. |

| RS | 2, 4 | Mitchell, J., Skouteris, H., McCabe, M., Ricciardelli, L.A., Milgrom, J., Baur, L.A., …, Dwyer, G. (2012). Physical activity in young children: A systematic review of parental influences. Early Child Development and Care, 182(11), 1411–1437, doi:10.1080/03004430.2011.619658. |

| RS | 2, 4 | Morgan, C., Novak, I., & Badawi, N. (2013). Enriched environments and motor outcomes in cerebral palsy: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatrics, 132(3), e735-e746, doi:10.1542/peds.2012-3985. |

| RS | 1 | Nicolson, A., Moir, L., & Millsteed, J. (2012). Impact of assistive technology on family caregivers of children with physical disabilities: A systematic review. Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology, 7(5), 345–349, doi:10.3109/17483107.2012.667194. |

| ES | 3 | Østensjø, S., Carlberg, E.B., & Vollestad, N.K. (2003). Everyday functioning in young children with cerebral palsy: Functional skills, caregiver assistance, and modifications of the environment. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 45, 603–612, doi:10.1017/S0012162203001105. |

| ES | 1, 3 | Østensjø, S., Carlberg, E.B., & Vøllestad, N.K. (2005). The use and impact of assistive devices and other environmental modifications on everyday activities and care in young children with cerebral palsy. Disability and Rehabilitation, 27, 849–861. |

| ES | 1 | Palaiologou, I. (2016). Children under five and digital technologies: Implications for early years pedagogy. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 24(1), 5–24, doi:10.1080/1350293X.2014.929876. |

| RS | 5 | Palisano, R.J., Chiarello, L.A., King, G.A., Novak, I., Stoner, T., & Fiss, A. (2012). Participation-based therapy for children with physical disabilities. Disability and Rehabilitation, 34, 1041–1052, doi:10.3109/09638288.2011.628740. |

| ES | 4 | Palisano, R.J., Tieman, B.L., Walter, S.D., Bartlett, D.J., Rosenbaum, P.L., Russell, D., & Hanna, S.E. (2003). Effect of environmental setting on mobility methods of children with cerebral palsy. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 45(2), 113–120, doi:10.1111/j.1469-8749.2003.tb00914.x. |

| RS | 4, 5 | Petrenchik, T.M., & King, G.A. (2011). Pathways to positive development: Childhood participation in everyday places and activities. In S. Bazyk (Ed.), Mental Health Promotion, Prevention, and Intervention with Children and Youth: A Guiding Framework for Occupational Therapy (pp. 71–94). Bethesda, MD, USA: AOTA Press. |

| ES | 5 | Rosenberg, L., Bart, O., Ratzon, N.Z., & Jarus, T. (2013). Personal and environmental factors predict participation of children with and without mild developmental disabilities. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 22(5), 658–671, doi:10.1007/s10826-012-9619-8. |

| RS | 2, 4 | Sallis, J.F., Prochaska, J.J., & Taylor, W.C. (2000). A review of correlates of physical activity of children and adolescents. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 32(5), 963–975, doi:10.1097/00005768-200005000-00014. |

| RS | 1 | Schlosser, R.W., & Sigafoos, J. (2006). Augmentative and alternative communication interventions for persons with developmental disabilities: Narrative review of comparative single-subject experimental studies. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 27(1), 1–29, doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2004.04.004. |

| RS | 5 | Spagnola, M., & Fiese, B.H. (2007). Family routines and rituals: A context for development in the lives of young children. Infants and Young Children, 20(4), 284–299, doi:10.1097/01.IYC.0000290352.32170.5a. |

| ES | 4 | Sugiyama, T., Okely, A.D., Masters, J.M., & Moore, G.T. (2012). Attributes of child care centers and outdoor play areas associated with preschoolers’ physical activity and sedentary behavior. Environment and Behavior, 44(3), 334–339, doi:10.1177/0013916510393276. |

| RS | 4 | Tremblay, L., Boudreau-Larivière, C., & Cimon-Lambert, K. (2012). Promoting physical activity in preschoolers: A review of the guidelines, barriers, and facilitators for implementation of policies and practices. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie Canadienne, 53(4), 280–290, doi:10.1037/a0030210. |

| ES | 5 | Trivette, C.M., Dunst, C.J., & Hamby, D. (2004). Sources of variation in and consequences of everyday activity settings on child and parenting functioning. Perspectives in Education, 22(2), 17–35. Retrieved from http://search.sabinet.co.za/pie/. |

| RS | 3 | Trivette, C.M., Dunst, C.J., Hamby, D.W., & O’Herin, C.E. (2010). Effects of different types of adaptations on the behavior of young children with disabilities. Research Brief (Tots N Tech Research Institute), 4(1), 1–26. Retrieved from http://www.puckett.org/returns_investments_tots_n_tech.php. |

| RS | 5 | Trivette, C.M., Dunst, C.J., Simkus, A., & Hamby, D.W. (2013). Methods for increasing child participation in everyday learning opportunities. Everyday Child Language Learning Reports, Number 7, 1–7. Retrieved from http://www.cecll.org/download/ECLLReport_7_LearnOps.pdf. |

| RS | 4, 5 | Wachs, T.D. (1999). Celebrating complexity: Conceptualization and assessment of the environment. In S.L. Friedman & T.D. Wachs (Eds.), Measuring environment across the life span: Emerging methods and concepts (pp. 357–392). Washington, DC, USA: American Psychological Association. |

| RS | 2 | Ward, D.S., Vaughn, A., McWilliams, C., & Hales, D. (2010). Interventions for increasing physical activity at child care. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 42(3), 526–534, doi:10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181cea406. |

| RS | 2 | Waters, E., de Silva-Sanigorski, A., Hall, B.J., Brown, T., Campbell, K.J., Gao, Y., …, Summerbell, C.D. (2011). Interventions for preventing obesity in children. Cochrane Reviews. Retrieved from http://www.cochrane.org/CD001871/PUBHLTH_interventions-for-preventing-obesity-in-children. |

Appendix C

| Type of Evidence | Checklist a | Sources of Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| RS | 3, 4 | Adler, K., Salanterä, S., Leino-Kilpi, H., & Grädel, B. (2015). An integrated literature review of the knowledge needs of parents with children with special health care needs and of instruments to assess these needs. Infants and Young Children, 28(1), 46–71, doi:10.1097/IYC.0000000000000028. |

| RS | 1 | Aikens, N., & Akers, L. (2011). Background Review of Existing Literature on Coaching. Washington, DC, USA: Mathematica Policy Research. Retrieved from http://www.first5la.org/files/07110_502.2CoachingLitRev_FINAL_07072011.pdf. |

| RS | 3 | Andresen, P.A., & Telleen, S.L. (1992). The relationship between social support and maternal behaviors and attitudes: A meta-analytic review. American Journal of Community Psychology, 20, 753–774. |

| ES | 3, 4 | Armstrong, M.I., Birnie-Lefcovitch, S., & Ungar, M.T. (2005). Pathways between social support, family well being, quality of parenting, and child resilience: What we know. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 14, 269–281, doi:10.1007/s10826-005-5054-4. |

| ES | 3 | Bailey, D.B., Jr., Nelson, L., Hebbler, K., & Spiker, D. (2007). Modeling the impact of formal and informal supports for young children with disabilities and their families. Pediatrics, 120, 992–1001, doi:10.1542/peds.2006-2775. |

| RS | 2, 3, 4 | Cunningham, B.J., & Rosenbaum, P.L. (2014). Measure of Processes of Care: A review of 20 years of research. Devlopmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 56(5), 445–452, doi:10.1111/dmcn.12347. |

| ES | 2, 3, 4 | Davis, K., & Gavidia-Payne, S. (2009). The impact of child, family, and professional support characteristics on the quality of life in families of young children with disabilities. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 34(2), 153–162, doi:10.1080/13668250902874608. |

| RS | 2, 3, 4 | Dempsey, I., & Keen, D. (2008). A review of processes and outcomes in family-centered services for children with a disability. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 28, 42–52, doi:10.1177/0271121408316699. |

| ES | 3 | Diaz, P., Stahl, J., Lovis-McMahon, D., Kim, S.H.Y., & Kwan, V.S.Y. (2013). Pathways to health services utilization: Overcoming economic barriers through support mechanisms. Advances in Applied Sociology, 3(4), 193–198, doi:10.4236/aasoci.2013.34026. |

| RS | 2, 3, 4 | Dunst, C.J. (2002). Family-centered practices: Birth through high school. Journal of Special Education, 36, 139–147, doi:10.1177/00224669020360030401. |

| ES | 2 | Dunst, C.J., Hamby, D.W., & Brookfield, J. (2007). Modeling the effects of early childhood intervention variables on parent and family well-being. Journal of Applied Quantitative Methods, 2, 268–288. |

| RS | 2, 3 | Dunst, C.J., & Trivette, C.M. (2009a). Capacity-building family systems intervention practices. Journal of Family Social Work, 12(2), 119–143, doi:10.1080/10522150802713322. |

| RS | 2, 3, 4 | Dunst, C.J., & Trivette, C.M. (2009). Meta-analytic structural equation modeling of the influences of family-centered care on parent and child psychological health. International Journal of Pediatrics, 2009, 1–9, doi:10.1155/2009/596840. |

| RS | 1, 2, 3, 4 | Dunst, C.J., Trivette, C.M., & Hamby, D.W. (2006). Family Support Program Quality and Parent, Family and Child Benefits. Asheville, NC, USA: Winterberry Press. |

| RS | 2, 3, 4 | Dunst, C.J., Trivette, C.M., & Hamby, D.W. (2007). Meta-analysis of family-centered helpgiving practices research. Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews, 13, 370–378, doi:10.1002/mrdd.20176. |

| RS | 1, 2, 3, 4 | Dunst, C.J., Trivette, C.M., & Hamby, D.W. (2008). Research synthesis and meta-analysis of studies of family-centered practices. Asheville, NC, USA: Winterberry Press. |

| RS | 3, 4 | Dunst, C.J., Trivette, C.M., & Jodry, W. (1997). Influences of social support on children with disabilities and their families. In M. Guralnick (Ed.), The Effectiveness of Early Intervention (pp. 499–522). Baltimore, MD, USA: Brookes. |

| RS | 3 | Guralnick, M.J. (2008). Family influences on early development: Integrating the science of normative development, risk and disability, and intervention. In K. McCartney & D. Phillips (Eds.), Blackwell Handbook of Early Childhood Development (pp. 44–61). Oxford, England: Blackwell. |

| ES | 3 | Guralnick, M.J., Hammond, M.A., Neville, B., & Connor, R.T. (2008). The relationship between sources and functions of social support and dimensions of child-and-parent-related stress. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 52, 1138–1154, doi:10.1111/j.1365-2788.2008.01073.x. |

| RS | 1, 3 | Halgunseth, L.C. (2009). Family engagement, diverse families and early childhood education programs: An integrated review of the literature. Young Children, 64(5), 56–58. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.libproxy.lib.unc.edu/ docview/197647848/fulltextPDF/6AE90A99362645CEPQ/11?accountid+14244. |

| RS | 1, 3 | Halgunseth, L.C., Peterson, A., Stark, D.R., & Moodie, S. (2009). Family Engagement, Diverse Families, and Early Childhood Education Programs: An Integrated Review of the Literature. Retrieved from http://www.buildinitiative.org/portals/0/uploads/documents/resource-center/diversity-and-equity-toolkit/halgunseth.pdf. |

| RS | 4 | Hassall, R., & Rose, J. (2005). Parental cognitions and adaptation to the demands of caring for a child with an intellectual disability: A review of the literature and implications for clinical interventions. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 33, 71–88. |

| RS | 3 | Hogan, B.E., Linden, W., & Najarian, B. (2002). Social support interventions: Do they work? Clinical Psychology Review, 22, 381–440. |

| ES | 2, 3 | King, G., King, S., Rosenbaum, P., & Goffin, R. (1999). Family-centered caregiving and well-being of parents of children with disabilities: Linking process with outcome. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 24, 41–53. |

| RS | 2, 3, 4 | King, S.M., Teplicky, R., King, G., & Rosenbaum, P. (2004). Family-centered service for children with cerebral palsy and their families: A review of the literature. Seminars in Pediatric Neurology, 11, 78–86, doi:10.1016/j.spen.2004.01.009. |

| RS | 2, 3, 4 | Kitson, A., Marshall, A., Bassett, K., & Zeitz, K. (2013). What are the core elements of patient-centred care? A narrative review and synthesis of the literature from health policy, medicine and nursing. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 69(1), 4–15, doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2012.06064.x. |

| RS | 1, 2, 3 | Knopf, H.T., & Swick, K.J. (2008). Using our understanding of families to strengthen family involvement. Early Childhood Education Journal, 35, 419–427, doi:10.1007/s10643-007-0198-z. |

| RS | 2, 4 | Kuhlthau, K.A., Bloom, S., Van Cleave, J., Knapp, A.A., Romm, D., Klatka, K., …, Perrin, J.M. (2011). Evidence for family-centered care for children with special health care needs: A systematic review. Academic Pediatrics, 11(2), 136–143, doi:10.1016/j.acap.2010.12.014. |

| RS | 2, 3, 4 | Kyzar, K.B., Turnbull, A.P., Summers, J.A., & Gómez, V.A. (2012). The relationship of family support to family outcomes: A synthesis of key findings from research on severe disability. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 37(1), 31–44, doi:10.2511/027494812800903247. |

| RS | 1, 3 | Mahoney, G., & Nam, S. (2011). The parenting model of developmental intervention. International Review of Research in Developmental Disabilities, 41, 74–118, doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-386495-6.00003-5. |

| ES | 4 | Mello, M.M., Burns, J.P., Truog, R.D., Studdert, D.M., Puopolo, A.L., & Brennan, T.A. (2004). Decision making and satisfaction with care in the pediatric intensive care unit: Findings from a controlled clinical trial. Pediatric Critical Care Medicine, 5(1), 40–47. |

| RS | 1 | Mortensen, J.A., & Mastergeorge, A.M. (2014). A meta-analytic review of relationship-based interventions for low-income families with infants and toddlers: Facilitating supportive parent-child interactions. Infant Mental Health Journal, 35(4), 336–353, doi:10.1002/imhj.21451. |

| RS | 2, 3, 4 | Rosenbaum, P., King, S., Law, M., King, G., & Evans, J. (1998). Family-centred service: A conceptual framework and research review. Physical and Occupational Therapy In Pediatrics, 18(1), 1–20. |

| ES | 1, 3 | Swanson, J., Raab, M., & Dunst, C.J. (2011). Strengthening family capacity to provide young children everyday natural learning opportunities. Journal of Early Childhood Research, 9, 66–80, doi:10.1177/1476718X10368588. |

| RS | 1, 3 | Tramonte, L., Gauthier, A.H., & Willms, J.D. (2015). Engagement and guidance: The effects of maternal parenting practices on children's development. Journal of Family Issues, 36(3), 396–420, doi:10.1177/0192513X13489959. |

| RS | 1, 2, 3, 4 | Trivette, C.M., & Dunst, C.J. (2007). Capacity-building family-centered helpgiving practices. Asheville, NC: Winterberry Press. |

| RS | 1, 2, 3 | Trivette, C.M., Dunst, C.J., & Hamby, D.W. (2010). Influences of family-systems intervention practices on parent-child interactions and child development. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 30, 3–19, doi:10.1177/0271121410364250. |

| ES | 1 | Trivette, C.M., Raab, M., & Dunst, C.J. (2014). Factors associated with Head Start staff participation in classroom-based professional development. Journal of Education and Training Studies, 2(4), 32–45, doi:10.11114/jets.v2i4.449. |

| RS | 3 | Turner, J.B., & Turner, R.J. (2013). Social relations, social integration, and social support. In C.S. Aneshensel, J.C. Phelan, & A. Bierman (Eds.), Handbook of the sociology of mental health (2nd ed., pp. 341–356). New York, NY: Springer. |

| RS | 3, 4 | Vanegas, S.B., & Abdelrahim, R. (2016). Characterizing the systems of support for families of children with disabilities: A review of the literature. Journal of Family Social Work, 19(4), 286–327, doi:1080/10522158.2016.1218399. |

| RS | 1, 3 | Vu, J.A., Hustedt, J.T., Pinder, W.M., & Han, M. (2015). Building early relationships: A review of caregiver–child interaction interventions for use in community-based early childhood programmes. Early Child Development and Care, 185(1), 138–154, doi:10.1080/03004430.2014.908864. |

| RS | 3 | Wills, T.A., & Ainette, M.G. (2012). Social networks and social support. In A. Baum, T.A. Revenson, & J. Singer (Eds.), Handbook of Health Psychology (2nd ed., pp. 465–492). New York, NY, USA: Psychology Press. |

Appendix D

| Type of Evidence | Checklist a | Sources of Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| RS | 1, 2, 3 | Aikens, N., & Akers, L. (2011). Background Review of Existing Literature on Coaching. Washington, DC, USA: Mathematica Policy Research. Retrieved from http://www.first5la.org/files/07110_502.2CoachingLitRev_FINAL_07072011.pdf. |

| RS | 2, 3 | Camargo, S.P.H., Rispoli, M., Ganz, J., Hong, E.R., Davis, H., & Mason, R. (2014). A review of the quality of behaviorally-based intervention research to improve social interaction skills of children with ASD in inclusive settings. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44, 2096–2116, doi:10.1007/s10803-014-2060-7. |

| RS | 1 | Crawford, S.K., Stafford, K.N., Phillips, S.M., Scott, K.J., & Tucker, P. (2014). Strategies for inclusion in play among children with physical disabilities in childcare centers: An integrative review. Physical and Occupational Therapy In Pediatrics, 34(4), 404–423 doi:10.3109/01942638.2014.904470. |

| RS | 2 | Dunst, C.J., & Kassow, D.Z. (2007). Characteristics of Interventions Promoting Parental Sensitivity to Child Behavior. Asheville, NC, USA: Winterberry Press. |

| ES | 1, 3 | Dunst, C.J., Raab, M., & Hamby, D.W. (2016). Interest-based everyday child language learning. Revista de Logopedia, Foniatria y Audiologia, 36, 153–161, doi:10.1016/j.rlfa.2016.07.003. |

| ES | 1, 3 | Dunst, C.J., Trivette, C.M., & Raab, M. (2014). Everyday child language learning early intervention practices. Infants and Young Children, 27(3), 207–219, doi:10.1097/IYC.0000000000000015. |

| RS | 1, 2 | Fukkink, R.G., & Lont, A. (2007). Does training matter? A meta-analysis and review of caregiver training studies. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 22, 294–311, doi:10.1016/j.ecresq.2007.04.005. |

| RS | 1, 2, 3 | Han, H.S. (2014). Supporting early childhood teachers to promote children’s social competence: Components for best professional development practices. Early Childhood Education Journal, 42, 171–179, doi:10.1007/s10643-013-0584-7. |

| RS | 1, 2 | Hancock, T.B., & Kaiser, A.P. (2006). Enhanced milieu teaching. In R.J. McCauley & M.E. Fey (Eds.), Treatment of Language Disorders in Children (pp. 203–236). Baltimore, MD, USA: Paul H. Brookes Publishing. |

| RS | 1, 2 | Kaat-van den Os, T., Danielle, J.A., Jongmans, M.J., Volman, M.C., & Lauteslager, P.E. (2017). Parent-implemented language interventions for children with a developmental delay: A systematic review. Journal of Policy and Practice in lntellectual Disabilities, doi:10.1111/jppi.12181. |

| RS | 1, 2 | Kaiser, A.P., & Trent, J.A. (2007). Communication intervention for young children with disabilities: Naturalistic approaches to promoting development. In S.L. Odom, R.H. Horner, M.E. Snell, & J. Blacher (Eds.), Handbook of Developmental Disabilities (pp. 224–245). New York, NY, USA: Guilford Press. |

| RS | 1, 2, 3 | Koegel, L.K., Koegel, R.L., Fredeen, R.M., & Gengoux, G.W. (2008). Naturalistic behavioral approaches to treatment. In K. Chawarska, A. Klin, & F.R. Volkmar (Eds.), Autism spectrum disorders in infants and toddlers: Diagnosis, assessment, and treatment (pp. 207–242). New York, NY: Guilford Press. |

| RS | 1, 2 | Mahoney, G., Perales, F., Wiggers, B., & Herman, B. (2006). Responsive teaching: Early intervention for children with Down Syndrome and other disabilities. Down’s Syndrome: Research and Practice, 11, 18–28. |

| RS | 1, 3 | Marquis, J.G., Horner, R.H., Carr, E.G., Turnbull, A.P., Thompson, M., Behrens, G.A., …, Doolabh, A. (2000). A meta-analysis of positive behavior support. In R. Gersten, E.P. Schiller, & S. Vaughn (Eds.), Contemporary Special Education Research: Syntheses of the Knowledge Base on Critical Instructional Issues (Vol. 11, pp. 137–178). Mahwah, NJ, USA: Erlbaum. |

| RS | 1, 2 | Meadan, H., Ostrosky, M.M., Zaghlawan, H.Y., & Yu, S.Y. (2009). Promoting the social and communicative behavior of young children with autism spectrum disorders: A review of parent-implemented intervention studies. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 29, 90–104, doi:10.1177/0271121409337950. |

| RS | 2 | Odom, S.L., Vitztum, J., Wolery, R., Lieber, J., Sandall, S., Hanson, M.J., …, Horn, E. (2004). Preschool inclusion in the United States: A review of research from an ecological systems perspective. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 4, 17–49, doi:10.1111/J.1471-3802.2004.00016.x. |

| RS | 1, 2 | Peterson, P. (2004). Naturalistic language teaching procedures for children at risk for language delays. Behavior Analyst Today, 5, 404–424, doi:10.1037/h0100047. |

| RS | 1, 2, 3 | Pindiprolu, S.S. (2012). A review of naturalistic interventions with young children with autism. Journal of the International Association of Special Education, 13(1), 69–78. |

| RS | 2 | Raab, M., & Dunst, C.J. (2009). Magic seven steps to responsive teaching: Revised and updated. Asheville, NC: Winterberry Press. |

| RS | 2 | Raab, M., Dunst, C.J., Johnson, M., & Hamby, D.W. (2013). Influences of a responsive interactional style on young children's language acquisition. Everyday Child Language Learning Reports, Number 4, 1–23. Retrieved from http://www.cecll.org/download/ECLLReport_4_Responsive.pdf. |

| RS | 1, 3 | Rakap, S., & Parlak-Rakap, A. (2011). Effectiveness of embedded instruction in early childhood special education: A literature review. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 19, 79–96, doi:10.1080/1350293X.2011.548946. |

| RS | 1, 2 | Rakap, S., & Rakap, S. (2014). Parent-implemented naturalistic language interventions for young children with disabilities: A systematic review of single-subject experimental research studies. Educational Research Review, 13, 35–51, doi:10.1016/j.edurev.2014.09.001. |

| RS | 1, 2 | Roberts, M.Y., & Kaiser, A.P. (2011). The effectiveness of parent-implemented language interventions: A meta-analysis. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 20, 180–199, doi:10.1044/1058-0360(2011/10-0055). |

| RS | 1, 2, 3 | Rous, B., Hallam, R., Grove, J., Robinson, S., & Machara, M. (2003). Parent Involvement in Early Care and Education Programs: A Review of the Literature. Lexington, KY: University of Kentucky, Interdisciplinary Human Development Institute. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Beth_Rous/puclication/253661005_Parent_Involvement._in_Early_Care_and_Education_Programs_A_Review_of_the_Literature/links./56c26d4608ae2dc3eb8848b9.pdf. |

| RS | 1, 2, 3 | Schreibman, L., Dawson, G., Stahmer, A.C., Landa, R., Rogers, S.J., McGee, G.G., …, Halladay, A. (2015). Naturalistic developmental behavioral interventions: Empirically validated treatments for autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45, 2411–2428, doi:10.1007/s10803-015-2407-8. |

| RS | 1, 2 | Snyder, P.A., Rakap, S., Hemmeter, M.L., McLaughlin, T.W., Sandall, S., & McLean, M.E. (2015). Naturalistic instructional approaches in early learning: A systematic review. Journal of Early Intervention, 37(1), 69–97, doi:10.1177/1053815115595461. |

| RS | 1, 2 | Trembath, D., Mahler, N., & Hudry, K. (2016). Evidence from systematic review indicates that parents can learn to implement naturalistic interventions leading to improved language skills in their children with disabilities. Evidence-Based Communication Assessment and Intervention, 10(2), 101–107, doi:10.1080/17489539.2016.1231387. |

| ES | 3 | VanDerHeyden, A.M., Snyder, P., Smith, A., Sevin, B., & Longwell, J. (2005). Effects of complete learning trials on child engagement. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 25, 81–94. |

| RS | 1, 2, 3 | Wolery, M. (1994). Instructional strategies for teaching young children with special needs. In M. Wolery & J.S. Wilbers (Eds.), Including Children with Special Needs in Early Childhood Programs (pp. 119–140). Washington, DC, USA: National Association for the Education of Young Children. |

| ES | 1, 2 | Woods, J., Kashinath, S., & Goldstein, H. (2004). Effects of embedding caregiver-implemented teaching strategies in daily routines on children's communication outcomes. Journal of Early Intervention, 26, 175–193. |

| RS | 1 | Woods, J.J., Wilcox, M.J., Friedman, M., & Murch, T. (2011). Collaborative consultation in natural environments: Strategies to enhance family-centered supports and services. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 42, 379–392, doi:10.1044/0161-1461(2011/10-0016). |

Appendix E

| Type of Evidence | Checklist a | Sources of Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| RS | 1 | Aikens, N., & Akers, L. (2011). Background Review of Existing Literature on Coaching. Washington, DC, USA: Mathematica Policy Research. Retrieved from http://www.first5la.org/files/07110_502.2CoachingLitRev_FINAL_07072011.pdf. |

| RS | 1, 4 | Bakermans-Kranenburg, M.J., van IJzendoorn, M.H., & Juffer, F. (2003). Less is more: Meta-analyses of sensitivity and attachment interventions in early childhood. Psychological Bulletin, 129, 195–215. |

| RS | 2, 3 | Crawford, S.K., Stafford, K.N., Phillips, S.M., Scott, K.J., & Tucker, P. (2014). Strategies for inclusion in play among children with physical disabilities in childcare centers: An integrative review. Physical and Occupational Therapy In Pediatrics, 34(4), 404–423, doi:10.3109/01942638.2014.904470. |

| RS | 1, 4 | de Wolff, M.S., & van IJzendoorn, M.H. (1997). Sensitivity and attachment: A meta-analysis on parental antecedents of infant attachment. Child Development, 68, 571–591. |

| RS | 1, 3, 4 | Dunst, C.J. (2007). Social-Emotional Consequences of Response-Contingent Learning Opportunities. Asheville, NC, USA: Winterberry Press. |

| RS | 1, 3 | Dunst, C.J., Gorman, E., & Hamby, D.W. (2010). Effcts of adult verbal and vocal contingent responsiveness on increases in infant vocalizations. CELLreviews, 3(1), 1–11. Retrieved from http://www.earlyliteracylearning.org/cellreviews/cellreviews_v3_n1.pdf. |

| RS | 1, 4 | Dunst, C.J., & Kassow, D.Z. (2008). Caregiver sensitivity, contingent social responsiveness, and secure infant attachment. Journal of Early and Intensive Behavior Intervention, 5, 40–56. Retrieved from http://www.jeibi.com/. |

| RS | 1, 3, 4 | Dyches, T.T., Smith, T.B., Korth, B.B., Roper, S.O., & Mandleco, B. (2012). Positive parenting of children with developmental disabilities: A meta-analysis. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 33, 2213–2220, doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2012.06.015. |

| RS | 1, 3, 4 | Eshel, N., Daelmans, B., Cabral de Mello, M., & Martines, J. (2006). Responsive parenting: Interventions and outcomes. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 84(12), 991–998, doi:10.1590/S0042-96862006001200016. |

| RS | 1, 3, 4 | Fukkink, R.G., & Lont, A. (2007). Does training matter? A meta-analysis and review of caregiver training studies. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 22, 294–311, doi:10.1016/j.ecresq.2007.04.005. |

| RS | 2, 3, 4 | Han, H.S. (2014). Supporting early childhood teachers to promote children’s social competence: Components for best professional development practices. Early Childhood Education Journal, 42, 171–179, doi:10.1007/s10643-013-0584-7. |

| RS | 1, 3, 4 | Landry, S.H., Taylor, H., Guttentag, C., & Smith, K.E. (2008). Responsive parenting: Closing the learning gap for children with early developmental problems. In L.M. Glidden (Ed.), International Review of Research in Mental Retardation (1st ed., Vol. 36). New York, NY, USA: Academic Press. |

| ES | 1, 3, 4 | Lohaus, A., Keller, H., Ball, J., Elben, C., & Voelker, S. (2001). Maternal sensitivity: Components and relations to warmth and contingency. Parenting: Science and Practice, 1, 267–284. |

| RS | 1, 3, 4 | Mahoney, G., & Nam, S. (2011). The parenting model of developmental intervention. International Review of Research in Developmental Disabilities, 41, 74–118, doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-386495-6.00003-5. |

| RS | 1, 3, 4 | Mesman, J., Van IJzendoorn, M.H., & Bakermans-Kranenburg, M.J. (2012). Unequal in opportunity, equal in process: Parental sensitivity promotes positive child development in ethnic minority families. Child Development Perspectives, 6, 207–319, doi:10.1111/j.1750-8606.2011.00223.x. |

| RS | 1, 3 | Mooney-Doyle, K., Deatrick, J.A., & Horowitz, J.A. (2015). Tasks and communication as an avenue to enhance parenting of children birth-5 years: An integrative review. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 30(1), 184–207, doi:10.1016/j.pedn.2014.03.002. |

| RS | 1, 3, 4 | Mortensen, J.A., & Mastergeorge, A.M. (2014). A meta-analytic review of relationship-based interventions for low-income families with infants and toddlers: Facilitating supportive parent-child interactions. Infant Mental Health Journal, 35(4), 336–353, doi:10.1002/imhj.21451. |

| RS | 1, 3 | Murza, K.A., Schwartz, J.B., Hahs-Vaughn, D.L., & Nye, C. (2016). Joint attention interventions for children with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, 51(3), 236–251, doi:10.1111/1460-6984.12212. |

| RS | 1, 4 | Nievar, M.A., & Becker, B.J. (2008). Sensitivity as a privileged predictor of attachment: A second perspective on De Wolff and van Ijzendoorn’s meta-analysis. Social Development, 17, 102–114, doi:10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00417.x. |

| RS | 1, 2, 3 | Odom, S.L., & Diamond, K.E. (1998). Inclusion of young children with special needs in early childhood education: The research base. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 13, 3–25. |

| RS | 2, 3 | Odom, S.L., Vitztum, J., Wolery, R., Lieber, J., Sandall, S., Hanson, M.J., …, Horn, E. (2004). Preschool inclusion in the United States: A review of research from an ecological systems perspective. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 4, 17–49, doi:10.1111/J.1471-3802.2004.00016.x. |

| RS | 1, 3, 4 | Paschall, K.W., & Mastergeorge, A.M. (2016). A review of 25 years of research in bidirectionality in parent-child relationships: An examination of methodological approaches. International Journal of Behavior and Development, 40, 422–451, doi:10.1177/0165025415607379. |

| RS | 1, 3 | Pennington, L., Goldbart, J., & Marshall, J. (2004). Interaction training for conversational partners of children with cerebral palsy: A systematic review. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, 39, 151–170, doi:10.1080/13682820310001625598. |

| RS | 1, 3 | Raab, M., Dunst, C.J., Johnson, M., & Hamby, D.W. (2013). Influences of a responsive interactional style on young children’s language acquisition. Everyday Child Language Learning Reports, Number 4, 1–23. Retrieved from http://www.cecll.org/download/ECLLReport_4_Responsive.pdf. |

| RS | 1, 3, 4 | Richter, L. (2004). The Importance of Caregiver-Child Interactions for the Survival and Healthy Development of Young Children: A Review. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, Department of Child and Adolescent Health and Development. |

| RS | 1, 3, 4 | Roggman, L.A., Boyce, L.K., & Innocenti, M.S. (2008). Developmental Parenting: A Guide for Early Childhood Practitioners. Baltimore, MD, USA: Paul H. Brookes. |

| RS | 1, 3, 4 | Shonkoff, J.P., & Phillips, D.A. (Eds.). (2000). From Neurons to Neighborhoods: The Science of Early Childhood Development. Washington, DC, USA: National Academy Press. |

| RS | 1, 3, 4 | Tramonte, L., Gauthier, A.H., & Willms, J.D. (2015). Engagement and guidance: The effects of maternal parenting practices on children's development. Journal of Family Issues, 36(3), 396–420, doi:10.1177/0192513X13489959. |

| RS | 1, 3, 4 | Vu, J.A., Hustedt, J.T., Pinder, W.M., & Han, M. (2015). Building early relationships: A review of caregiver-child interaction interventions for use in community-based early childhood programmes. Early Child Development and Care, 185(1), 138–154, doi:10.1080/03004430.2014.908864. |

| RS | 1, 3, 4 | Ware, J. (2016). Creating a Responsive Environment for People with Profound and Multiple Learning Difficulties (2nd ed.). London, UK: David Fulton Publishers. |

| RS | 1, 3 | Warren, S.F., & Brady, N.C. (2007). The role of maternal responsivity in the development of children with intellectual disabilities. Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews, 13, 330–338, doi:10.1002/mrdd.20177. |

| RS | 1, 3, 4 | White, P.J., O’Reilly, M., Streusand, W., Levine, A., Sigafoos, J., Lancioni, G.E., …, Aguilar, J. (2011). Best practices for teaching joint attention: A systematic review of the intervention literature. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 5, 1283–1295, doi:10.1016/j.rasd.2011.02.003. |

| RS | 1, 2 | Williams, K.E., Berthelsen, D., Nicholson, J.M., & Viviani, M. (2015). Systematic literature review: Research on Supported Playgroups. Brisbane, Australia: Queensland University of Technology. |

Appendix F

| Type of Evidence | Checklist a | Sources of Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| RS | 1, 2 | Abelson, M.A., & Woodman, R.W. (1983). Review of research on team effectiveness: lmplications for teams in schools. School Psychology Review, 12(2), 125–136. Retrieved from http://psycnet.apa.org/psycinfo/1983-31253-001. |

| RS | 1, 2 | Agote, L., Aramburu, N., & Lines, R. (2016). Authentic leadership perception, trust in the leader, and followers’ emotions in organizational change processes. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 52(1), 35–63, doi:10.1177/0021886315617531. |

| ES | 1 | Allen, N.E., Foster-Fishman, P.G., & Salem, D.A. (2002). Interagency teams: A vehicle for service delivery reform. Journal of Community Psychology, 30, 475–497. |

| RS | 1, 2 | Beal, D.J., Cohen, R.R., Burke, M.J., & McLendon, C.L. (2003). Cohesion and performance in groups: A meta-analytic clarification of construct relations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 989–1004. |

| RS | 1, 2 | Bell, S.T. (2004). Setting the stage for effective teams: A meta-analysis of team design variables and team effectiveness (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from http://oaktrust.library.tamu.edu/bitstream/handle/1969.1/1110/etd-tamu-2004B-PSYC-Bell-3.pdf?sequence=1. |

| RS | 1, 2 | Bosch, M., Faber, M.J., Cruijsbery, J., Voerman, G.E., Leatherman, S., Grol, R.P.T.M., …, Wensing, M. (2009). Effectiveness of patient care teams and the role of clinical expertise and coordination. Medical Care Research and Review, 66(6_suppl), 5S–35S, doi:10.1177/1077558709343295. |

| RS | 1, 2 | Burke, C.S., Stagl, K.C., Klein, C., Goodwin, G.F., Salas, E., & Halpin, S.M. (2006). What type of leadership behaviors are functional in teams? A meta-analysis. Leadership Quarterly 17, 288–307. |

| RS | 1, 2 | Burke-Smalley, L.A., & Hutchins, H.M. (2007). Training transfer: An integrative literature review. Human Resource Development Review. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/249674889 doi:10.1177/1534484307303035. |

| ES | 1, 2 | Cavalier, J.C., Klein, J.D., & Cavalier, F.J. (1995). Effects of cooperative learning on performance, attitude, and group behaviors in a technical team environment. Educational Technology Research and Development, 43(3), 61–72. Retrieved from https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2FBF02300456?LI=true doi:10.1007/BF02300456. |

| RS | 1, 2 | Coulthard, N. (2009). Service trends and practitioner competencies in early childhood intervention: A review of the literature. Retrieved from https://www.eciavic.org.au/documents/item/26. |

| RS | 1, 2 | D'Innocenzo, L., Mathieu, J.E., & Kukenberger, M.R. (2016). A meta-analysis of different forms of shared leadership: Team performance relations. Journal of Management, 42(7), 1964–1991, doi:10.1177/0149206314525205. |

| RS | 3 | Dunst, C.J. (2002). Family-centered practices: Birth through high school. Journal of Special Education, 36, 139–147, doi:10.1177/00224669020360030401. |

| RS | 1 | Dunst, C.J., Trivette, C.M., & Hamby, D.W. (2010). Meta-analysis of the effectiveness of four adult learning methods and strategies. International Journal of Continuing Education and Lifelong Learning, 3(1), 91–112. |

| RS | 1, 2, 3 | Finello, K.M. (2011). Collaboration in the assessment and diagnosis of preschoolers: Challenges and opportunities. Psychology in Schools, 48(5), 442–253, doi:10. 1002/pits.20566. |

| RS | 1, 2 | Foster-Fishman, P.G., Berkowitz, S.L., Lounsbury, D.W., Jacobson, S., & Allen, N.A. (2001). Building collaborative capacity in community coalitions: A review and integrative framework. American Journal of Community Psychology, 29, 241–261. |

| RS | 1, 2 | Gully, S.M. (2002). A meta-analysis of team-efficacy, potency, and performance: Interdependence and level of analysis as moderators of observed relationships. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 819–832. |

| RS | 2, 3 | Guralnick, S., Ludwig, S., & Englander, R. (2014). Domain of competence: Systems-based practice. Academic Pediatrics, 14, S70-S79. Retrieved from https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PDFs/Milestones/Systems-basedPracticePediatrics.pdf doi:10.1016/j.acap.2013.11.015. |

| RS | 1, 2 | Guzzo, R.A., & Dickson, M.W. (1996). Teams in organizations: Recent research on performance and effectiveness. Annual Review of Psychology, 47, 307–338. |

| RS | 1, 2 | Herlihy, M. (2016). Conceptualising and facilitating success in interagency collaborations: Implications for practice from the literature. Journal of Psychologists and Counsellors in Schools, 26(1), 117–124, doi:10.1017/jgc.2016.11. |

| RS | 1 | Hillier, S.L., Civetta, L., & Pridham, L. (2010). A systematic review of collaborative models for health and education professionals working in school settings and implications for training. Education for Health, 23(3), 1–12. |

| RS | 1, 2 | Hoch, J.E. (2014). Shared leadership, diversity, and information sharing in teams. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 29(5), 541–564, doi:10.1108/JMP-02-2012-0053. |

| RS | 3 | King, S.M., Teplicky, R., King, G., & Rosenbaum, P. (2004). Family-centered service for children with cerebral palsy and their families: A review of the literature. Seminars in Pediatric Neurology, 11, 78–86, doi:10.1016/j.spen.2004.01.009. |

| RS | 1 | Klein, C., DiazGranados, D., Salas, E., Le, H., Burke, C.S., Lyons, R., & Goodwin, G.F. (2009). Does team building work? Small Group Research, 40(2), 181–222, doi:10.1177/1046496408328821. |

| ES | 1, 3 | Larsson, M. (2000). Organising habilitation services: Team structures and family participation. Child: Care, Health and Development, 26(6), 501–514, doi:10.1046/j.1365-2214.2000.00169.x. |

| RS | 1 | Lemieux-Charles, L., & McGuire, W. (2006). What do we know about health care team effectiveness: A review of the literature. Medical Care Research and Review, 63, 263–300. |

| RS | 1, 2 | Lumsden, G., Lumsden, D., & Wiethoff, C. (2014). Communicating in groups and teams: Sharing leaderships (5th ed.). Boston: Wadsworth. |

| RS | 1 | Mattessich, P.W., & Monsey, B.R. (1992). Collaboration: What Makes It Work. A Review of Research Literature on Factors Influencing Successful Collaboration. St. Paul, MN, USA: Amherst H. Wilder Foundation. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED390758). |

| RS | 1, 2 | Mickan, S., & Rodger, S. (2000). Characteristics of effective teams: A literature review. Australian Health Review, 23(3), 201–208, doi:10.1071/AH000201. |

| RS | 3 | Nash, J.K. (1990). Public Law 99-457: Facilitating family participation on the multidisciplinary team. Journal of Early Intervention, 14(4), 318–326, doi:10.1177/105381519001400403. |

| RS | 1, 2 | Nicolaides, V.C., LaPort, K.A., Chen, T.R., Tomassetti, A.J., Weis, E.J., Zaccaro, S.J., & Cortina, J.M. (2014). The shared leadership of teams: A meta-analysis of proximal, distal, and moderating relationships. The Leadership Quarterly, 25, 923–942, doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2014.06.006. |

| RS | 1, 2, 3 | Nijhuis, B.J.G., Reinders-Messelink, H.A., de Blécourt, A.C.E., Olijve, C.V.G., Groothoff, J.W., Nakken, H., & Postema, K. (2007). A review of salient elements defining team collaboration in paediatric rehabilitation. Clinical Rehabilitation, 21(3), 195–211, doi:10.1177/0269215506070674. |

| RS | 1, 2 | Ruddy, G., & Rhee, K. (2005). Transdisciplinary teams in primary care for the underserved: A literature review. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 16, 248–256. |

| RS | 1, 2 | Salas, E., DiazGranados, D., Klein, C., Burke, C.S., Stagl, K.C., Goodwin, G.F., & Halpin, S.M. (2008). Does team training improve team performance? A meta-analysis. Human Factors, 50(6), 903–933, doi:10.1518/001872008X375009. |

| RS | 1 | Salisbury, C.L., & Dunst, C.J. (1997). Home, school, and community partnerships: Building inclusive teams. In B. Rainforth & J. York-Barr (Eds.), Collaborative Teams for Students with Severe Disabilities (2nd ed., pp. 57–87). Baltimore, MD, USA: Brookes. |

| RS | 1, 2 | Stajkovic, A.D., Lee, D., & Nyberg, A.J. (2009). Collective efficacy, group potency, and group performance: Meta-analyses of their relationships, and test of a mediation model. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(3), 814–828, doi:10.1037/a0015659. |

| RS | 1, 2 | Stewart, G.L. (2006). A meta-analytic review of relationships between team design features and team performance. Journal of Management 32(1), 29–55. |

| ES | 1, 2 | Strauss, K., Benvenuto, A., Battan, B., Siracusano, M., Terribili, M., Curatolo, P., & Fava, L. (2015). Promoting shared decision making to strengthen outcome of young children with autism spectrum disorders: The role of staff competence. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 38, 48–63, doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2014.11.016. |

| RS | 1, 2 | Wang, D., Waldman, D.A., & Zhang, Z. (2014). A meta-analysis of shared leadership and team effectiveness. Journal of Applied Psychology, 99(2), 181–198, doi:10.1037/a0034531. |

| RS | 1, 2 | Weaver, S.J., Rosen, M.A., Salas, E., Baum, K.D., & King, H.B. (2010). Integrating the science of team training: Guidelines for continuing education. Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/49695589 doi:10.1002/chp.20085. |

| RS | 2 | Xyrichis, A., & Lowton, K. (2008). What fosters or prevents interprofessional teamworking in primary and community care? A literature review. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 45, 140–153, doi:10. I016j.ijnurstu.2007.0l.015. |

Appendix G

| Type of Evidence | Checklist a | Sources of Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| RS | 1 | Affleck, G., Tennen, H., & Rowe, J. (1991). Infants in Crisis: How Parents Cope with Newborn Intensive Care and Its Aftermath. New York, NY, USA: Springer-Verlag. |

| ES | 1 | Affleck, G., Tennen, H., Rowe, J., Roscher, B., & Walker, L. (1989). Effects of formal support on mothers' adaptation to the hospital-to-home transition of high-risk infants: The benefits and costs of helping. Child Development, 60, 488–501. |

| RS | 1 | Auger, K.A., Kenyon, C.C., Feudtner, C., & Davis, M.M. (2014). Pediatric hospital discharge interventions to reduce subsequent utilization: A systematic review. Journal of Hospital Medicine, 9(4), 251–260, doi:10.1002/jhm.2134. |

| RS | 3 | Baughan, C. (2012). An Examination of Predictive Factors Related to School Adjustment for Children with Disabilities Transitioning into formal School Settings. Retrieved from http://tigerprints.clemson.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1964&context=all_dissertations. |

| RS | 1 | Boykova, M. (2016). Transition from hospital to home in parents of preterm infants: A literature review. Journal of Perinatal & Neonatal Nursing, 30(4), 327–348, doi:10.1097/JPN.0000000000000211. |

| RS | 1 | Clow, P., Dunst, C.J., Trivette, C.M., & Hamby, D.W. (2005). Educational outreach (academic detailing) and physician prescribing practices. Cornerstones, 1(1), 1–9. Retrieved from http://www.puckett.org/Trace/cornerstones/cornerstones_vol1_no1.pdf. |

| RS | 1 | Desai, A.D., Popalisky, J., Simon, T.D., & Mangione-Smith, R.M. (2015). The effectiveness of family-centered transition processes from hospital settings to home: A review of the literature. Hospital Pediatrics, 5(4), 219–231, doi:10.1542/hpeds.2014-0097. |

| ES | 1, 2 | Dunst, C.J., & Bruder, M.B. (2006). Early intervention service coordination models and service coordinator practices. Journal of Early Intervention, 28, 155–165, doi:10.1177/105381510602800301. |

| RS | 1 | Dunst, C.J., & Gorman, E. (2006). Practices for increasing referrals from primary care physicians. Cornerstones, 2(5), 1–10. Retrieved from http://www.puckett.org/Trace/cornerstones/cornerstones_vol2_no5.pdf. |

| ES | 1 | Dunst, C.J., Trivette, C.M., Shelden, M., & Rush, D.D. (2006). Academic detailing as an outreach strategy for increasing referrals to early intervention. Snapshots, 2(3), 1–9. Retrieved from http://www.tracecenter.info/snapshots/snapshots_vol2_no3.pdf. |

| RS | 1 | Goyal, N.K., Teeters, A., & Ammerman, R.T. (2013). Home visiting and outcomes of preterm infants: A systematic review. Pediatrics, 132, 502–516, doi:10.1542/peds.2013-0077. |

| ES | 2 | Hadden, D.S. (1998). The Impact of Interagency Agreements Written to Facilitate the Transition from Early Intervention to Preschool. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/2142/80278. |

| RS | 1, 2, 3 | Herlihy, M. (2016). Conceptualising and facilitating success in interagency collaborations: Implications for practice from the literature. Journal of Psychologists and Counsellors in Schools, 26(1), 117–124, doi:10.1017/jgc.2016.11. |

| ES | 2 | Hoover, P.J. (2001). Mothers' Perceptions of the Transition Process from Early Intervention to Early Childhood Special Education: Related Stressors, Supports, and Coping Skills. Retrieved from https://theses.lib.vt.edu/theses/available/etd-04242001-221132/unrestricted/Hoover.Paula.PDF. |

| RS | 2, 3 | Kagan, S.L., & Neuman, M.J. (1998). Lessons from three decades of transition research. Elementary School Journal, 98, 365–379. |

| RS | 1 | Lopez, G.L., Anderson, K.H., & Feutchinger, J. (2012). Transition of premature infants from hospital to home life. Neonatal Network, 31(4), 207–214. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3662297/. |

| RS | 2 | Malone, D.G., & Gallagher, P. (2009). Transition to special education: A review of the literature. Early Education and Development, 20(4), 584–602, doi:10.1080/10409280802356646. |

| RS | 3 | O’Brien, M. (1991). Promoting successful transition into school: A review of current intervention practices (ERIC No. ED 374 921). Retrieved from http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED374921.pdf. |

| RS | 2 | Pang, Y. (2010). Facilitating family involvement in early intervention to preschool transition. The School Community Journal, 20(2), 183–198. |

| RS | 3 | Peters, S. (2010). Literature Review: Transition from Early Childhood Education to School. Wellington, New Zealand: Ministry of Education, New Zealand. Retrieved from http://ece.manukau.ac.nz/__data/assets/pdf_file/0008/85841/956_ECELitReview.pdf. |

| ES | 2 | Podvey, M.C., & Hinojosa, J. (2009). Transition from early intervention to preschool special education services: Family-centered practice that promotes positive outcomes. Journal of Occupational Therapy, Schools, & Early Intervention, 2(2), 73–83, doi:10.1080/19411240903146111. |

| RS | 1, 2, 3 | Rice, M.L., & O’Brien, M. (1990). Transitions: Times of change and accommodation. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 9(4), 1–14, doi:10.1177/027112149000900402. |

| RS | 2, 3 | Rosenkoetter, S., Schroeder, C., Rous, B., Hains, A., Shaw, J., & McCormick, K. (2009). A Review of Research in Early Childhood Transition: Child and Family Studies (Technical Report #5). Retrieved from http://www.niusileadscape.org/docs/FINAL_PRODUCTS/LearningCarousel/ResearchReviewTransition.pdf. |

| RS | 2, 3 | Rous, B.S., & Hallam, R.A. (2012). Transition services for young children with disabilities: Research and future directions. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 31(4), 232–240, doi:10.1177/0271121411428087. |

| RS | 2, 3 | Skouteris, H., Watson, B., & Lum, J. (2012). Preschool children’s transition to formal schooling: The importance of collaboration between teachers, parents and children. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 37(4), 78–85. |

| RS | 1 | Smith, V.C., Hwang, S.S., Dukhovny, D., Young, S., & Pursley, D.M. (2013). Neonatal intensive care unit discharge preparation, family readiness and infant outcomes: Connecting the dots. Journal of Perinatology, 33, 415–421, doi:10.1038/jp.2013.23. |

| RS | 1, 2, 3 | Vogler, P., Crivello, G., & Martin, W. (2008). Early childhood transitions research: A review of concepts, theory, and practice, Working Paper 48. The Open University. Retrieved from http://oro.open.ac.uk/16989/1/Vogler_et_al_Transitions_PDF.DAT.pdf. |

| ES | 1 | Williams, P.D., & Williams, A.R. (1997). Transition from hospital to home by mothers of preterm infants: Path analysis results over three time periods. Families, Systems, & Health, 15(4), 429–446, doi:10.1037/h0089838. |

| RS | 3 | Yeboah, D.A. (2002). Enhancing transition from early childhood phase to primary education: Evidence from the research literature. Early Years, 22(1), 51–68, doi:10.1080/09575140120111517. |

References

- National Institute of Standards and Technology. 2017–2018 Baldrige Excellence Framework (Education); Quality Press: Milwaukee, WI, USA, 2017.

- Blazey, M.L. Insights to Performance Excellence 2013–2014: Understanding the Integrated Management System and the Baldrige Criteria; ASQ Quality Press: Milwaukee, WI, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Gawande, A. Better: A Surgeon's Notes on Performance; Metropolitan Books: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Gawande, A. The Checklist Manifesto: How to Get Things Right; Metropolitan Books: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Oxman, A.D. Systematic reviews: Checklists for review articles. Br. Med. J. 1994, 309, 648–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roper, N.; Dunst, C.J. Early childhood intervention competency checklists. CASEtools 2006, 2, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, C. Credible Checklists and Quality Questionnaires: A User-Centered Design Method; Morgan Kaufman: Waltham, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Karges-Bone, L. A Checklist for Everything: Simple Assessment Tools for Student Projects, Grants and Parent Communication; Teaching and Learning Company: Carthage, IL, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]