In this section we recall concepts about hyperplane arrangements, Fan’s graph, characteristic varieties and resonance varieties. Each subsection concludes with several lemmas that are used to prove the main theorems of this paper.

2.3. Graphs of Fan Type

In this paper, we will use a graph defined by Fan in [

7]. We recall the definition of the graph, and then give lemmas that will be useful later.

Definition 2.1. Let be an arrangement of n distinct projective lines in . Let M denote the set of points in where two or more lines from the arrangement intersect and let be the subset of M consisting of points with multiplicity greater than or equal to three.

Define a graph denoted by

called a

graph of Fan type of the arrangement

as follows.

Let the set of points be the vertices of .

For each line , let . If the set is not empty, then choose an ordering of the points in given by . For each , choose a simple arc in that connects to , avoids all points in M, and avoids all arcs previously chosen. Let be the set of simple arcs chosen for the line . The edges of will consist of the set of arcs .

The vertices of graphs of Fan type are uniquely defined. However, the edges are not uniquely defined since any line containing more than two multiple points admits many orderings of those points that leads to different sets of edges. This situation motivates the following definition.

Definition 2.2. Let denote the set of all possible graphs of Fan type for the arrangement

We introduce the following definition for the sake of brevity.

Definition 2.1. If an arrangement in is the union of two nontrivial subarrangements and that intersect in exactly points of multiplicity two, then we say that is a general position partition of the arrangement.

We use the phrase “general position” since two distinct lines in the complex plane intersect transversely in a point of multiplicity two or have no point of intersection. We collect some useful properties of graphs of Fan type of an arrangement that imply has a decone with a general position partition.

Lemma 2.3. Let be a projective line arrangement in . If a graph of Fan type is disconnected, then has a decone with a general position partition.

Proof. Let C be a connected component of the graph F and let denote the set of all lines in that contain a vertex in C. Let . The set is non-empty as otherwise the graph F would be connected.

Let and . Suppose that and intersect in a point of multiplicity greater than two. (As the lines are in projective space, the multiplicity of their intersection is at least two.) As , then by definition the line contains a vertex in the connected component C of the graph F. By definition of graphs of Fan type, this means either is a vertex of the component C or there is a path from another vertex in C contained in to . In either case, this implies that contains a vertex in the connected component C; therefore, is in the set , which contradicts the fact that . Therefore, and intersect in a point of multiplicity two.

Let L be an arbitrary line in the arrangement . Then the decone has two components and , the images of and under the decone operation. As the arrangements and were in general position in projective space, their images are in general position in affine space after the decone. Therefore, has a decone with a general position partition. ☐

Lemma 2.4. Let be a projective arrangement of lines in containing at least three lines. If there is a line H in such that all multiple points contained in H are points of multiplicity two, then has a decone with a general position partition.

Proof. Let L denote any line in that is not H. Then the decone may be written as two subarrangements and . As all lines in intersect H in double points, the image of these lines will also intersect the image of H in double points in . Therefore, and are in general position. Whereby, we conclude that has a decone with a general position partition. ☐

Lemma 2.5. Suppose that all graphs in are connected and every hyperplane in contains a point of multiplicity at least three. If there is a graph such that F has an edge that is not part of a simple circuit, then has a decone with a general position partition.

Proof. Recall that a simple circuit is a path in a graph such that the first and last vertices of the path are the same, no vertices are repeated (except for the first vertex as the last vertex) and no edges are repeated.

Let L be the line in containing the edge e that is not part of a simple circuit in F. Let v and w denote the vertices of the edge e . The graph has two connected components. If not, then there is a simple path P from v to w. Combining the path P with the edge e would create a simple circuit containing e, which is a contradiction.

Denote the components of by and where is the component containing v and is the component containing w. Let denote the set of lines in containing vertices in except for L. Likewise let denote the set of lines in containing vertices in except for L. Since every line in contains a higher order multiple point, each line besides L must be in either or . Therefore, . The sets of lines and are disjoint. If they have a line, H, in common, then H would contain a vertex that is connected to v in and a vertex that is connected to w in . By definition of graphs of Fan type, there is a path between these two vertices, hence the vertices v and w are connected, which is a contradiction.

Let and be chosen arbitrarily. Suppose that and intersect in a point of multiplicity greater than two in . (We know the lines intersect in a point of at least multiplicity two as they are in .) Then will be a vertex in all graphs of Fan type. As , by definition there is a path from the point v to z in the graph . Likewise, as there is a path from the point z to the w in Combining these paths creates a path from v to w. This yields a contradiction as v and w are in distinct connected components. Therefore and intersect in a point of multiplicity two. As these lines were chosen arbitrarily, we see that and intersect in general position in .

Therefore, the arrangement has two subarrangements and the images of and respectively. These arrangements intersect in general position, therefore has a decone with a general position partition. ☐

Corollary 2.1. If does not have a decone with a general position partition, then for every it follows that F is connected, every edge in F is contained in a simple circuit and every hyperplane in contains a vertex in F.

Theorem 2.1. Let be an arrangement of projective lines. If there is an edge e on a line L such that for all with every simple circuit containing e has at least two edges contained in the line L, then has a decone with a general position partition.

Proof. From Lemma 2.3, we know that if any choice of Fan’s graph is disconnected, then the conclusion follows. Therefore, we assume that any choice of graph of Fan type from the collection is connected. Let be any choice of graph of Fan type that contains the edge e as described in the statement of the theorem. Let v and w denote the vertices of the edge e.

Let E denote the set of edges in F that are contained in the line L. Then, is a subgraph of F . If is connected, then there is a simple path from v to w. However, combining this path with the edge e would create a simple circuit in the graph F, but this contradicts the hypothesis that every simple circuit containing the edge e in the graph F has at least two edges contained in the line L since the path comes from Therefore the graph has at least two connected components and w and v are in different components.

Let denote the set of lines in that contain vertices with paths to v in . Let . Both of these arrangements are non-empty as v and w represent points of multiplicity greater than three. Let and be chosen arbitrarily. Suppose is a point of multiplicity greater than two. Then by definition of there is a path from the vertex to v. Therefore, by definition of the set , we have . However, this is a contradiction as . Therefore, the lines and intersect in a point of multiplicity two in the arrangement . As these lines were chosen arbitrarily, the arrangements and are in general position. Using L as the line at infinity will result in the arrangement that has a general position partition given by . ☐

2.4. Characteristic Varieties

The characteristic varieties can be defined for any space that is homotopy equivalent to CW-complex with finitely many cells in each dimension [

10]. In this paper, we restrict out attention to spaces that are complements of hyperplane arrangements.

Let be an arrangement of hyperplanes in . As the fundamental group has torsion-free abelianization with rank n, the character variety is identified with . A generating set for a presentation of the fundamental group is given by where each is a meridional loop around whose orientation is given by the complex structure.

Definition 2.3 ([

10]). The

characteristic varieties of the arrangement

are the cohomology jumping loci of

with coefficients in the rank 1 local systems over

:

where

determines a representation

,

that induces a rank one local system

.

In this paper, we shall only be concerned with the varieties where

and

. The characteristic varieties

depend (up to a monomial automorphism of the algebraic torus

) only on the fundamental group

(Subsection 2.5, [

10]), therefore we will also use the notation

.

2.4.1. Direct Products of Groups

Let denote an arrangement n of hyperplanes and let denote the fundamental group of the complement of the arrangement. Further suppose that where and have ranks and respectively. As G may be finitely presented with rank equal to the number of hyperplanes in the arrangement, it follows that and may also be finitely presented and . The characteristic variety is a subset of the algebraic torus .

Theorem 2.2. If is the fundamental group of an arrangement of n hyperplanes, then the characteristic varieties are isomorphic to Proof. Let

and

be the canonical CW complexes generated by finite presentations for

and

respectively. By Theorem 3.2 in [

11],

As the characteristic varieties depend only on the group, there are monomial automorphisms of the algebraic torus

such that

Thus, the varieties are isomorphic as desired. ☐

Corollary 2.1. Let be a projective arrangement of lines in .

If then is isomorphic to Proof. From Lemma 2.2, we conclude that . Also, . Therefore, using Theorem 2.2 twice, the conclusion follows. ☐

2.5. Resonance Varieties

Let

be an arrangement in

. Then, the cone of the arrangement

is an arrangement in

. We denote the projectivization of the arrangement in

by

. The intersection poset is the set of non-empty intersections of hyperplanes in the arrangement and is denoted by

The rank of an element

is equal to the codimension of the space

X in

. The rank

n elements are denoted by

.

Falk introduced the resonance varieties associated to an arrangement in [

12]. We recall the basic notation and ideas here and direct the interested reader to Falk’s original work for more information. Let

be the graded Orlik–Solomon algebra associated to an arrangement generated by

where

is associated to

. If we fix an element

, then the map

defined by left multiplication creates a complex

as

. Notice that

where

. Therefore, we associate each

ω with a vector

.

As

is a complex, we denote the cohomology of the complex by

. Finally, we define the

resonance varieties associated to the arrangement by

The following definition follows from Lemma 3.14 in [

12]:

Definition 2.4. Let

be a central arrangement of hyperplanes. For each

with

X contained in at least three hyperplanes in

, the

local component of X in

is given by

We will denote this component by the simpler notation

when there is no confusion about the arrangement.

The next lemma follows easily from the definition as each vertex corresponds to a point in of multiplicity at least three, hence a rank two component of .

Lemma 2.6. Let be a projective arrangement of lines in Each vertex in a graph of Fan type of induces a non-trivial local component of the resonance varieties in .

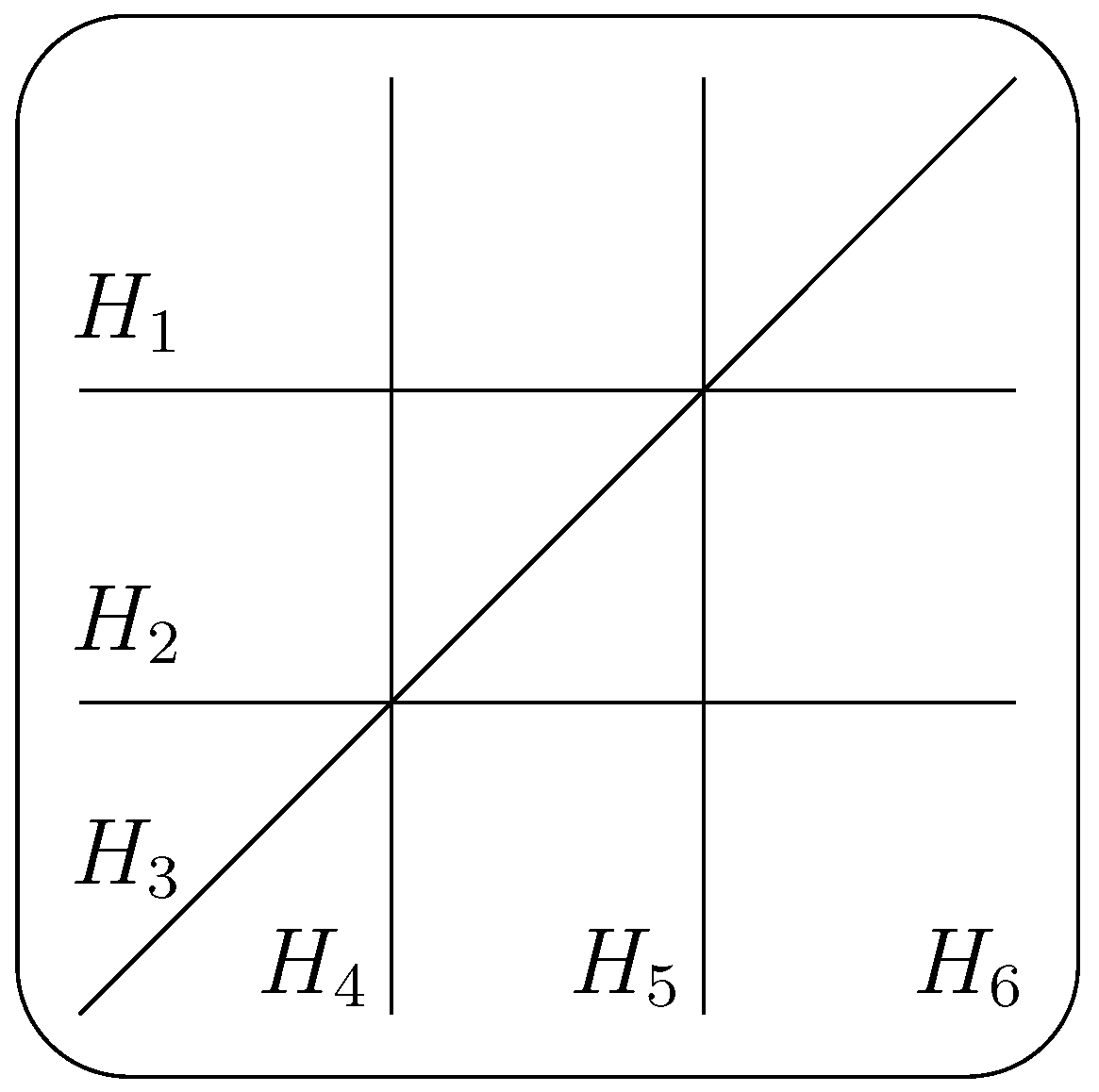

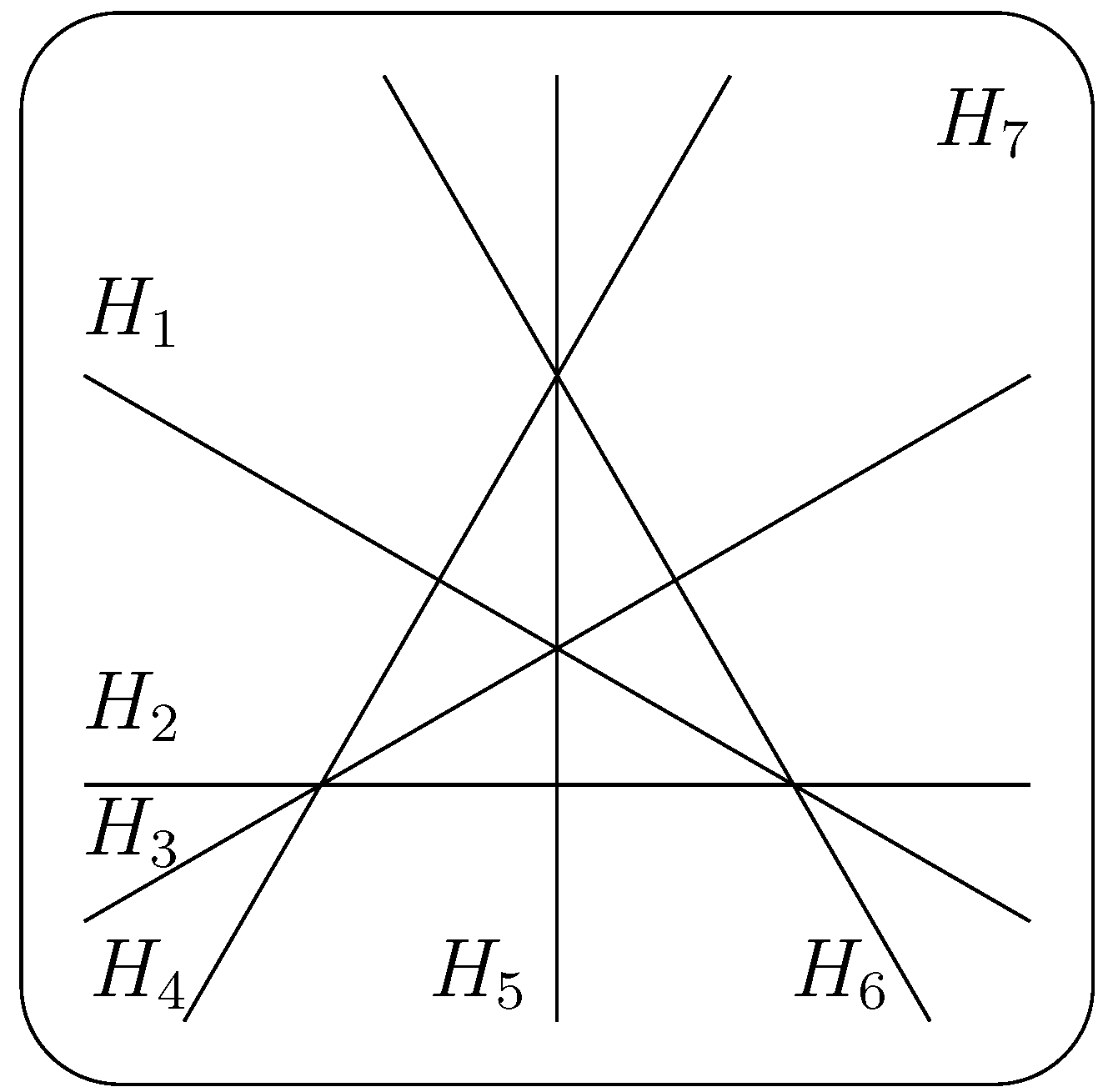

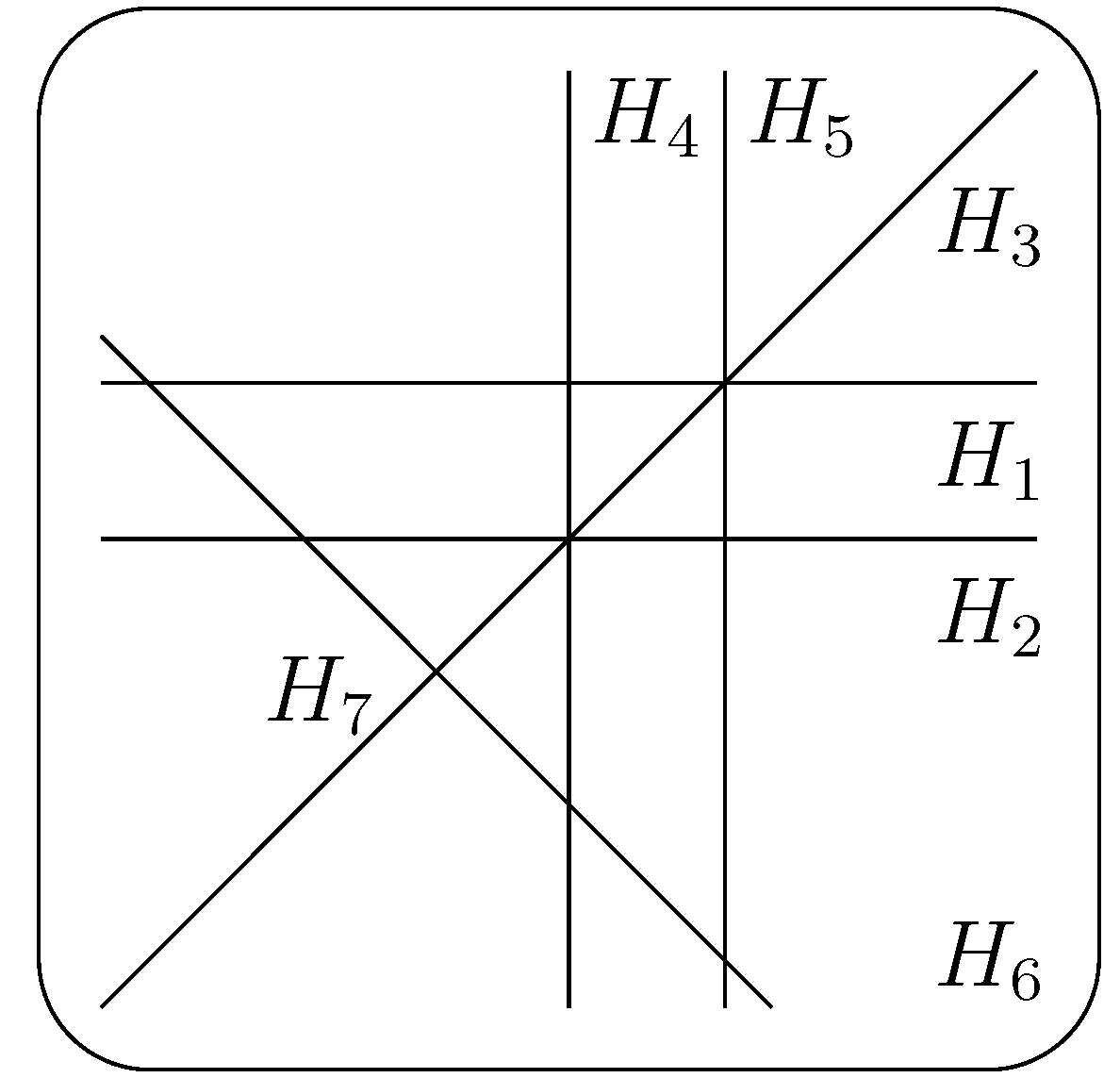

Example 2.1. Consider the arrangement

in

defined by the polynomial

. This is the rank 3 braid arrangement with associated matroid

. We may depict the real part of the projectivization of this arrangement in

Figure 1. Using the labeling of the lines as in the figure, we have four local components in

. Let

denote the point in

where the lines labelled by

intersect. The four local components are

Let

be the canonical set of basis vectors for

. Associate each hyperplane

with the vector

. Then we may write

as the span of the vectors

and

.

Notation 2.1. Let be any variety that is the union of linear subspaces. Then, each point may be regarded as a vector . Denote by the linear subspace of spanned by the vectors

Theorem 2.3. Let be a central arrangement of n hyperplanes such thatwhere .

Then, the resonance variety decomposes into a union of varieties such that the intersection of and is the trivial vector. Proof. By Theorem 5.2 in [

11], the tangent cone

of the characteristic variety

at the point

coincides with the resonance variety

. More explicitly, there is a linear isomorphism

from the tangent space of

at

to

such that

.

Let be a coordinate ring for and let be a coordinate ring for the tangent space of in Then the variety is defined by an ideal generated by the union of an ideal and the set . Therefore, the tangent cone of the variety at is defined by the ideal generated by an ideal and the set . In a similar manner, the tangent cone of at denoted by is defined by the ideal generated by an ideal and the set . Therefore, the tangent cone of V at is given by . From the definition of the ideals generating and , the varieties are orthogonal. Therefore, the subspaces and intersect only at the origin.

As , there is a monomial automorphism g of inducing a linear isomorphism of tangent cones such that . Combined with the map , we have . Define . Then, as linear isomorphisms preserve unions and intersections of linear subspaces, the conclusion of the theorem follows. ☐

Theorem 2.4. Let be an arrangement of projective lines in such that>where the varieties are not trivial. Let be the decomposition of the resonance variety from Theorem 2.3. If either or does not have local components, then has a decone with a general position partition. Proof. Suppose that both and do not have local components. Then there are no multiple points in the arrangement . Deconing with respect to any line will result in an arrangement of lines in general position. Thus an arrangement that has a general position partition.

Without loss of generality, assume

has local components and

does not have local components. Let

be the set of lines in

containing points that induce local components in

and let

. If

, then every line in the arrangement induces a local component contained in

. Then

. However, as

[

12],

must be the trivial subspace. By hypothesis,

is not trivial, therefore its tangent cone and the variety

are not trivial subspaces. Therefore we have a contradiction and may conclude that

and

are not empty. In fact,

as it contains at least one local component.

Any line and must intersect in a point of multiplicity two. If they intersect in a higher order point, the intersection induces a local component, but the lines in do not induce local components. Therefore, and intersect in general position in

Pick any line and consider . The images of and intersect transversely in , thus has a decone with a general position partition. ☐