Elderly Men’s Experience of Information Material about Melanoma—A Qualitative Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Design

2.2. Setting

2.3. Data Collection

| Age | Numbers |

| 65 | 6 |

| 70 | 6 |

| 75 | 3 |

| n = 15 | |

| Marital status | Numbers |

| Married | 11 |

| Cohabiting | 1 |

| Single | 3 |

| n = 15 |

2.4. Data Analysis

| Meaning unit | Condensed content | Coding | Subcategory | Category |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ... I thought it was positive that caregivers act within the area, that was my thought. I could see my body but I have not found anything ... but I’m not exactly worried ... but as I said, I think it’s positive ... | Positive that healthcare is engaged in educating people | Knowing what skin cancer is | Availability—to use | Security—to act |

2.5. Ethical Considerations

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Results

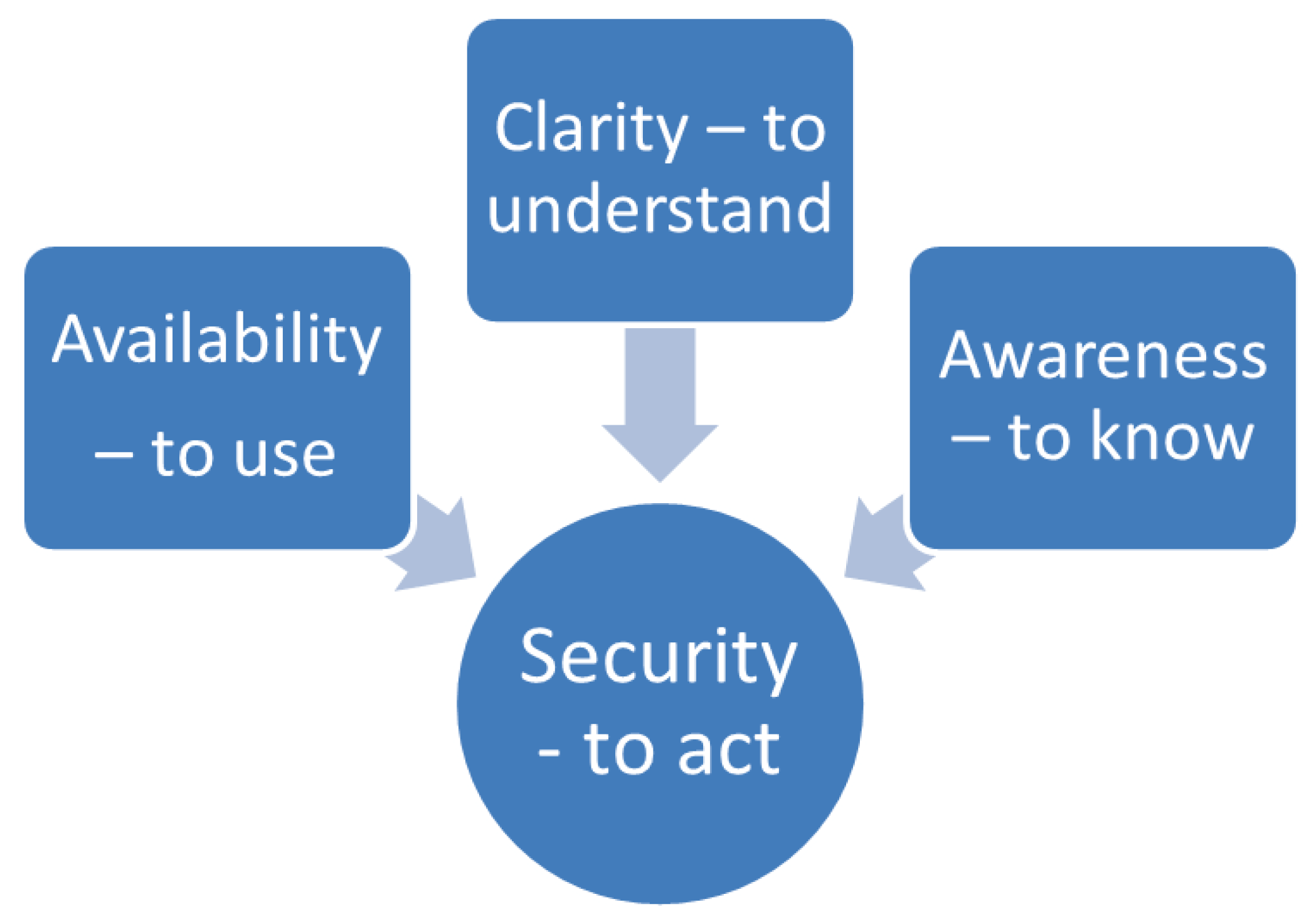

3.1.1. Security—To Act

“ ... I thought it was positive that it takes care of that problem, that was my thought, but I see the greater part of my body and I have not found anything ... but I’m not exactly worried due to no particular or way to do it I heard (laughs) ... no, I am not worried if I get home like this but as I said, I think it’s positive ...”

3.1.2. Availability—To Use

“... It is important to send it right to me (a target group of men over 65 years) and there’s no living man who does not open a letter, for me it’s quite obvious, if it does not perhaps show that it is advertising for any crap that I’m not interested in, then I throw it away ... Can you afford it and if you have the ability and technology to address it to the audience you want to reach, then it’s best ...”

3.1.3. Clarity—To Understand

“... You embrace so much more from an image than from a little text, a text you just skim through and you might not read anything special but a picture catches you a little bit differently, so I think this is really good and also you can see then if there is anything that you yourself may have to do ...”

3.1.4. Awareness—To Know

“... It was the personal approach where and then the folder that showed what it was all about, and images and some text, then I think most people read them, it should not be too much body text, but it has to be direct like that ... I do not just go and wait for it to happen, that I should suffer so to speak ...”

3.2. Discussion

3.3. Limitations

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest

References

- Black, L.; Runken, C.; Eaddy, M.; Shah, M. Chronic disease prevalence and burden in elderly men: An analysis of medical claims data. J. Health Care Finance 2007, 33, 68–78. [Google Scholar]

- Cummins, D.; Cummins, J.; Pantle, H.; Silverman, M.; Leonard, A.; Chanmugam, A. Cutaneous malignant melanoma. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2006, 81, 500–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markovic, S.N.; Erickson, L.A.; Rao, R.D.; McWilliams, R.R.; Kottschade, L.A.; Creagan, E.T.; Weenig, R.H.; Hand, J.L.; Pittelkow, M.R.; Pockaj, B.A.; et al. Malignant melanoma in the 21st century, part 1: Epidemiology, risk factors, screening, prevention, and diagnosis. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2007, 82, 364–380. [Google Scholar]

- Knight, C. Looking at skin cancer and effective sun protection. Br. J. Sch. Nurs. 2011, 6, 220–224. [Google Scholar]

- Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions, SALAR; National Board of Health and Welfare. Öppna jämförelser av cancersjukvårdens kvalitet och effektivitet. Jämförelser mellan landsting 2011; (In Swedish). Socialstyrelsen: Stockholm, Sweden, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Renzi, C.; Mastroeni, S.; Mannooranparampil, M.; Passarelli, F.; Potenza, C.; Pasquini, P. Reliability of self-reported information on skin cancer among elderly patients with squamous cell carcinoma. AEP 2011, 21, 551–554. [Google Scholar]

- Hodgetts, J. Diagnosis and management of malignant melanoma. CancerNurs. Pract. 2011, 10, 30–37. [Google Scholar]

- Wheller, T. Psychological consequences of malignant melanoma: Patients’ experiences and preferences. Nurs. Stand. 2006, 21, 42–46. [Google Scholar]

- Guile, K.; Nicholson, S. Does knowledge influence melanoma-prone behavior? Awareness, exposure, and sun protection among five social groups. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2004, 31, 641–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheller, T. Nursing the patient with malignant melanoma: Early intervention. Br. J. Nurs. 2009, 18, 288–292. [Google Scholar]

- LaGasse, N. Plastic surgery: Plastic surgeon and cosmetic dermatologist: Complications and liability. J. Leg. Nurs. Consult. 2011, 22, 15–19. [Google Scholar]

- Foster, L. Raising men’s awareness of the need to monitor their health. Kai Tiaki Nurs. N. Z. 2012, 18, 16–17. [Google Scholar]

- Bungay, H.; Cappello, R. “As long as the doctors know what they are doing”: Trust or ambivalence about patient information among elderly men with prostate cancer? Eur. J. Cancer Care 2009, 18, 470–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, D. Changed men: The embodied impact of prostate cancer. Qual. Health Res. 2009, 19, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendias, E.; Paar, D. Perceptions of health and self-care learning needs of outpatients with HIV/AIDS. J. Commun. Health Nurs. 2007, 24, 49–64. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, G. Men health 2007: The need for action. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2007, 61, 1959–1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nokes, K.; Nwakeze, P. Assessing self-management information needs of persons living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2005, 19, 607–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swedish Agency for Health and care Services & National Board of Health, Öppna. Jämförelser av Cancersjukvårdens Kvalitet och Effektivitet. Jämförelser Mellan Landsting 2011; (In Swedish). Socialstyrelsen: Stockholm, Sweden, 2011.

- National Board of Health & Cancer fonden, Populärvetenskapliga Fakta om Cancer Cancer. I Siffror 2009; (In Swedish). Socialstyrelsen: Stockholm, Sweden, 2009.

- Parks, C.; Turner, M.; Perry, M.; Lyons, R.; Chaney, C.; Hooper, E.; Conaway, M.R.; Burns, S.M. Educational needs: What female patients want from their cardiovascular health care providers. Med. Surg. Nurs. 2011, 20, 21–28. [Google Scholar]

- Koutsopoulou, S.; Papathanassoglou, E.; Katapodi, M.; Patiraki, E. A critical review of the evidence for nurses as information providers to cancer patients. J. Clin. Nurs. 2010, 19, 749–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shieh, S.-C.; Tung, H.-S.; Liang, S.-Y. Social support as influencing primary family caregiver burden in taiwanese patients with colorectal cancer. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2012, 44, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blows, E.; de Blas, J.; Scanion, K.; Richardson, A.; Ream, E. Information and support for older women with breast cancer. Cancer Nurs. Pract. 2011, 10, 31–37. [Google Scholar]

- Rosengren, K.; Athlin, E.; Segesten, K. Presence and availability: Staff conceptions of nursing leadership on an intensive care ward. J. Nurs. Manag. 2007, 15, 522–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosengren, K.; Bondas, T. Supporting “two-getherness”: Assumption for nurse managers working in a shared leadership model. Intens. Crit. Care Nurs. 2010, 26, 288–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelberg, J.; McIvor, A. Overcoming gaps in the management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in older patients. New insights. Drugs Aging 2010, 27, 367–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaglia, A.; Vercelli, M.; Lillini, R.; Mugno, E.; Coebergh, J.W.; Quinn, M.; Martinez-Garcia, C.; Capocaccia, R.; Micheli, A. Socio-economic factors and health care system characteristics related to cancer survival in the elderly. A population-based analysis in 16 European countries (ELDCARE project). Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2005, 54, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polit, D.; Beck, C.T. Nursing Research: Generating and Assessing Evidence for Nursing Practice; Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Cop: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Egberg Thyme, K.; Wiberg, B.; Lundman, B.; Hällgren Graneheim, U. Qualitative content analysis in art psychotherapy research: Concepts, procedures, and measures to reveal the latent meaning in pictures and the words attached to the pictures. Arts Psychother. 2013, 40, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Codex. Rules & Guidelines for Research. The Humanities and Social Sciences. Available online: http://www.codex.vr.se/en/forskninghumsam.shtml/ (accessed on 15 April 2013).

- Swedish Code of Statutes. 2010:659 Patientsäkerhetslagen. (Patient Safety Act). (In Swedish)Available online: http://www.socialstyrelsen.se/regelverk/lagarochforordningar/ (accessed on 27 October 2012).

- Swedish Agency for Health and care Services. Patient-Centeredness in Sweden’s Health System—An External Assessment and Six Steps for Progress. Available online: http://www.vardanalys.se/index.htm/ (accessed on 8 April 2013).

- Grosch, K.; Medvene, L.; Wolcott, H. Person-Centered caregiving instruction for geriatric nursing assistant students. J. Gerontol. Nurs. 2008, 34, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handy, P.; Sankar, N. Testicular self-examination—Knowledge of men attending a large Genito urinary medicine clinic. Health Educ. J. 2008, 67, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekman, I.; Wolf, A.; Olsson, L.-E.; Taft, C.; Dudas, K.; Schaufelberger, M.; Swedberg, K. Effects of person-centered care in patients with chronic heart failure: The PCC-HF study. Eur. Heart J. 2012, 33, 1112–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonovsky, A. Unravelling the Mystery of Health: How People Manage Stress and Stay Well; Jossey-Bass Inc.: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Crandall, L.; White, D.; Schuldheis, S.; Talerico, K.A. Initiating person-centered care practices in long-term care facilities. J. Gerontol. Nurs. 2007, 33, 47–56. [Google Scholar]

- King, S.; O’Brien, C.; Edelman, P.; Fazio, S. Evaluation of person-centered care essentials program: Importance of trainers in achieving targeted outcomes. Gerontol. Geriatr. Educ. 2011, 32, 379–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlström, E.; Ekman, I. Organisational culture and change: Implementing person-centered care. J. Health Organ. Manag. 2012, 26, 175–191. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley, S.L.; de Bellis, A.; Guerin, P.; Walters, B.; Wotherspoon, A.; Cecchin, M.; Paterson, J. Reenacted case scenarios for undergraduate healthcare students to illustrate person-centered care in dementia. Educ. Gerontol. 2010, 36, 809–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaye, L.; Crittenden, J.; Charland, J. Invisible older men: What we know about older men’s use of healthcare and social services. Generations 2008, 32, 9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Loiselle, C.; Dubios, S. The impact of multimedia informational intervention on healthcare service use among women and men newly diagnosed with cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2009, 32, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindström, B.; Eriksson, M. Salutogenesis. J. Epidemiol. Commun. Health 2005, 59, 440–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vugt, H.V.; Roobol, M.; Venderbos, L.; Joosten-van Zwanenburg, E.; Essink-Bot, M.; Steyerberg, E.; Bangma, C.; Korfage, I. Informed decision making on PSA testing for the detection of prostate cancer: An evaluation of a Leaflet with risk indicator. Eur. J. Cancer 2010, 46, 669–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davison, B.; Breckon, E. Factors influencing treatment decision making and information preferences of prostate cancer patients on active surveillance. Patient Educ. Couns. 2012, 87, 369–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, S. Developing a service to support men with testicular cancer. Cancer Nurs. Pract. 2010, 9, 14–21. [Google Scholar]

- Townsend, A. Support for men newly diagnosed with prostate cancer. Nurs. Stand. 2010, 25, 40–45. [Google Scholar]

- Mathers, S.; McKenzie, G.; Robertson, E. A necessary evil: The experiences of men with prostate cancer undergoing imaging procedures. Radiography 2011, 17, 284–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, D.; Kiely, M.; Smith, A.; Velikova, G.; House, A.; Selby, P. Anxiety disorders in cancer patients: Their nature, associations, and relation to quality of life. J. Clin. Oncol. 2002, 20, 3137–3148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenthal, W.G.; Cruess, D.G.; Schuchter, L.M.; Ming, M.E. Correspondence of recipient and provider perceptions of social support among patients diagnosed with or at risk for malignant melanoma. J. Health Psychol. 2003, 8, 705–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajdarevic, S.; Schmitt-Egenolf, M.; Brulin, C.; Sundbom, E.; Hörnsten, Å. Malignant melanoma: Gender patterns in care seeking for suspect marks. J. Clin. Nurs. 2011, 20, 2676–2684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamama-Raz, Y. Does psychological adjustment of melanoma survivors differs between genders? Psycho-Oncology 2012, 21, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tryggvadóttir, L.; Gislum, M.; Hakulinen, T.; Klint, Å.; Engholm, G.; Storm, H.H.; Bray, F. Trends in the survival of patients diagnosed with malignant melanoma of the skin in the Nordic countries 1964ߝ2003 followed up to the end of 2006. Acta Oncol. 2010, 49, 665–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalton, S.O.; Schüz, J.; Engholm, G.; Johansen, C.; Kjaer, S.K.; Steding-Jessen, M.; Storm, H.H.; Olsen, J.H. Social inequality in incidence of and survival from cancer in a populationbased study in Denmark, 1994ߝ2003: Summary of findings. Eur. J. Cancer. 2008, 44, 2074–2085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elo, S.; Kynga, S.H. The qualitative content analysis process. J. Adv. Nurs. 2008, 62, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2013 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Rosengren, K. Elderly Men’s Experience of Information Material about Melanoma—A Qualitative Study. Healthcare 2013, 1, 5-19. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare1010005

Rosengren K. Elderly Men’s Experience of Information Material about Melanoma—A Qualitative Study. Healthcare. 2013; 1(1):5-19. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare1010005

Chicago/Turabian StyleRosengren, Kristina. 2013. "Elderly Men’s Experience of Information Material about Melanoma—A Qualitative Study" Healthcare 1, no. 1: 5-19. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare1010005