Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for Inpatients with Psychosis (the REACH Study): Protocol for Treatment Development and Pilot Testing

Abstract

:1. Background

1.1. Summary

1.2. Rationale for the Current Project

2. Method

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Sample

2.3. Recruitment Procedures

2.4. Randomization

2.5. Treatment Conditions

2.5.1. Enhanced Treatment As Usual (eTAU)

2.5.2. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT)

- Acceptance is defined as one’s willingness to experience unwanted thoughts and feelings in the pursuit of a valued goal.

- Cognitive defusion involves taking a meta-cognitive perspective toward cognitions by treating thoughts as thoughts instead of as their literal content. For example, cognitive defusion of paranoid ideation would involve the patient taking the following perspective: “I’m noticing that I’m having the thought right now that…someone is trying to harm me.”

- Nonjudgmental attention to the present moment invokes the process of being mindful and aware of one’s ongoing experiences.

- Flexible perspective-taking involves recognizing the part of one’s self that is stable, consistent, and independent from transient mental events like thoughts and feelings.

- Personal values are defined as global, desired, and chosen life directions that make life worth living.

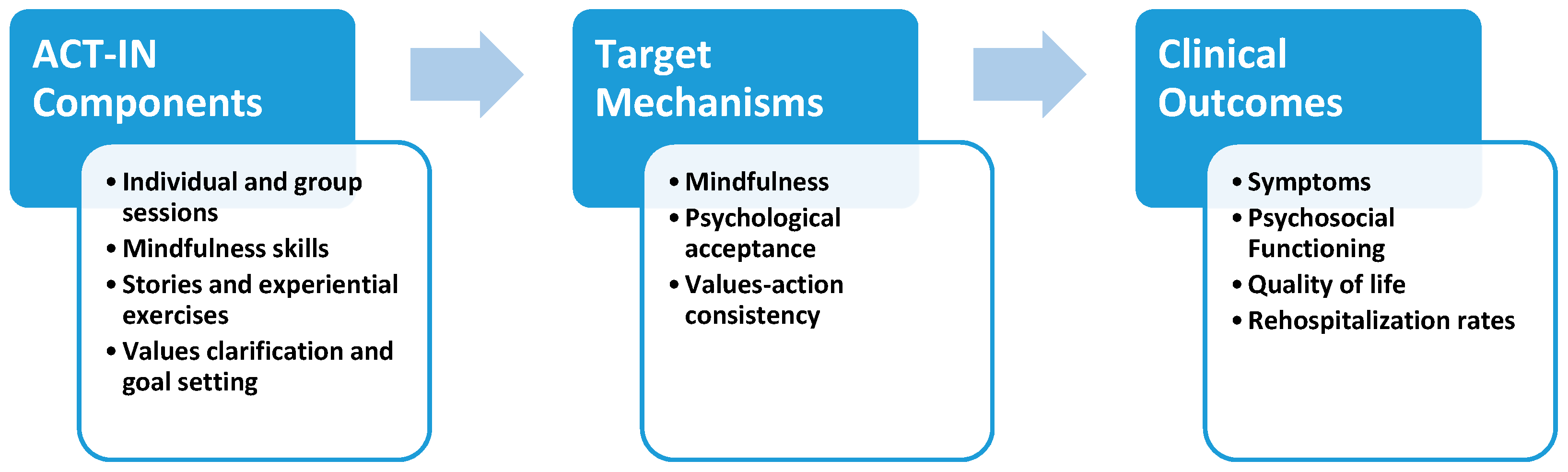

2.6. ACT for Inpatients (ACT-IN) Protocol

2.7. Study Therapists

2.8. Treatment Fidelity

2.9. Assessments

2.10. Assessors

2.11. Retention Efforts

3. Sample Size and Data Analysis Considerations

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Perala, J.; Suvisaari, J.; Saarni, S.I.; Kuoppasalmi, K.; Isometsa, E.; Pirkola, S.; Partonen, T.; Tuulio-Henriksson, A.; Hintikka, J.; Kieseppa, T.; et al. Lifetime prevalence of psychotic and bipolar I disorders in a general population. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2007, 64, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, C.J.L.; Lopez, A.D. The Global Burden of Disease; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Mueser, K.T.; McGurk, S.R. Schizophrenia. Lancet 2004, 363, 2063–2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, E.Q.; Birnbaum, H.G.; Shi, L.; Ball, D.E.; Kessler, R.C.; Moulis, M.; Aggarwal, J. The economic burden of schizophrenia in the United States in 2002. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2005, 66, 1122–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wheeler, A.; Robinson, E.; Robinson, G. Admissions to acute psychiatric inpatient services in Auckland, New Zealand: A demographic and diagnostic review. N. Z. Med. J. 2005, 118, U1752. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Young, L.D.; Harsch, H.H. Inpatient unit for combined physical and psychiatric disorders. Psychosomatics 1986, 27, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terkelsen, K.G.; Menikoff, A. Measuring the costs of schizophrenia. Implications for the post-institutional era in the US. Pharmacoeconomics 1995, 8, 199–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geller, J.L. A historical perspective on the role of state hospitals viewed from the era of the “revolving door”. Am. J. Psychiatry 1992, 149, 1526–1533. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sharfstein, S.S. Goals of inpatient treatment for psychiatric disorders. Annu. Rev. Med. 2009, 60, 393–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knapp, M.; Mangalore, R.; Simon, J. The global costs of schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 2004, 30, 279–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knapp, M. Costs of schizophrenia. Psychiatry 2005, 4, 33–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossau, C.D.; Mortensen, P.B. Risk factors for suicide in patients with schizophrenia: Nested case-control study. Br. J. Psychiatry 1997, 171, 355–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergen, J.; Hunt, G.; Armitage, P.; Bashir, M. Six-month outcome following a relapse of schizophrenia. Aust N. Z. J. Psychiatry 1998, 32, 815–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiden, P.J.; Olfson, M. Cost of relapse in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 1995, 21, 419–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jencks, S.F.; Williams, M.V.; Coleman, E.A. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 360, 1418–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tohen, M.; Stoll, A.L.; Strakowski, S.M.; Faedda, G.L.; Mayer, P.V.; Goodwin, D.C.; Kolbrener, M.L.; Madigan, A.M. The McLean First-Episode Psychosis Project: Six-month recovery and recurrence outcome. Schizophr. Bull. 1992, 18, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strasser, O.; Schmauss, M.; Messer, T. Rehospitalization rates of newly diagnosed schizophrenic patients on atypical neuroleptic medication. Psychiatr. Prax. 2004, 31 (Suppl 1), S38–S40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruscher, S.M.; de Wit, R.; Mazmanian, D. Psychiatric patients’ attitudes about medication and factors affecting noncompliance. Psychiatr. Serv. 1997, 48, 82–85. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lacro, J.P.; Dunn, L.B.; Dolder, C.R.; Leckband, S.G.; Jeste, D.V. Prevalence of and risk factors for medication nonadherence in patients with schizophrenia: A comprehensive review of recent literature. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2002, 63, 892–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caton, C.L.; Goldstein, J.M.; Serrano, O.; Bender, R. The impact of discharge planning on chronic schizophrenic patients. Hosp. Community Psychiatry 1984, 35, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaudiano, B.A. Cognitive behavior therapies for psychotic disorders: Current empirical status and future directions. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2005, 12, 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudiano, B.A. Is symptomatic improvement in clinical trials of cognitive-behavioral therapy for psychosis clinically significant? J. Psychiatr. Pract. 2006, 12, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rathod, S.; Phiri, P.; Kingdon, D. Cognitive behavioral therapy for schizophrenia. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2010, 33, 527–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tai, S.; Turkington, D. The evolution of cognitive behavior therapy for schizophrenia: Current practice and recent developments. Schizophr. Bull. 2009, 35, 865–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfammatter, M.; Junghan, U.M.; Brenner, H.D. Efficacy of psychological therapy in schizophrenia: Conclusions from meta-analyses. Schizophr. Bull. 2006, 32 (Suppl. 1), S64–S80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drury, V.; Birchwood, M.; Cochrane, R.; Macmillan, F. Cognitive therapy and recovery from acute psychosis: A controlled trial. I. Impact on psychotic symptoms. Br. J. Psychiatry 1996, 169, 593–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, S.; Tarrier, N.; Haddock, G.; Bentall, R.; Kinderman, P.; Kingdon, D.; Siddle, R.; Drake, R.; Everitt, J.; Leadley, K.; et al. Randomised controlled trial of cognitive-behavioural therapy in early schizophrenia: Acute-phase outcomes. Br. J. Psychiatry Suppl. 2002, 43, s91–s97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Startup, M.; Jackson, M.C.; Bendix, S. North Wales randomized controlled trial of cognitive behaviour therapy for acute schizophrenia spectrum disorders: Outcomes at 6 and 12 months. Psychol. Med. 2004, 34, 413–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moran, M. Psychosocial treatment rates for schizophrenia patients. Psychiatr. News 2003, 38, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Glick, I.D.; Sharfstein, S.S.; Schwartz, H.I. Inpatient psychiatric care in the 21st century: The need for reform. Psychiatr. Serv. 2011, 62, 206–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mullen, A. Mental health nurses establishing psychosocial interventions within acute inpatient settings. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2009, 18, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsh, J.; Boyle, J. Improving acute psychiatric hospital services according to inpatient experiences. A user-led piece of research as a means to empowerment. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2009, 30, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chadwick, P.; Hughes, S.; Russell, D.; Russell, I.; Dagnan, D. Mindfulness groups for distressing voices and paranoia: A replication and randomized feasibility trial. Behav. Cogn. Psychother. 2009, 37, 403–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, S.C.; Strosahl, K.D.; Wilson, K.G. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: An Experiential Approach to Behavior Change; Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association. Psychological Treatments. 2017. Available online: http://www.div12.org/psychological-treatments/treatments/acceptance-and-commitment-therapy-for-psychosis/ (accessed on 4 May 2017).

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT). 2010. Available online: https://contextualscience.org/039act_is_evidencebased039_says_us_government_agen (accessed on 4 May 2017).

- Walser, R.D.; Karlin, B.E.; Trockel, M.; Mazina, B.; Barr Taylor, C. Training in and implementation of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for depression in the Veterans Health Administration: Therapist and patient outcomes. Behav. Res. Ther. 2013, 51, 555–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, S.C.; Luoma, J.B.; Bond, F.W.; Masuda, A.; Lillis, J. Acceptance and commitment therapy: Model, processes and outcomes. Behav. Res. Ther. 2006, 44, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Öst, L.G. Efficacy of the third wave of behavioral therapies: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Behav. Res. Ther. 2008, 46, 296–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powers, M.B.; Zum Vörde Sive Vörding, M.B.; Emmelkamp, P.M. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: A meta-analytic review. Psychother. Psychosom. 2009, 78, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khoury, B.; Lecomte, T.; Gaudiano, B.A.; Paquin, K. Mindfulness interventions for psychosis: A meta-analysis. Schizophr. Res. 2013, 150, 176–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bach, P.; Hayes, S.C. The use of acceptance and commitment therapy to prevent the rehospitalization of psychotic patients: A randomized controlled trial. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2002, 70, 1129–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bach, P.; Hayes, S.C.; Gallop, R. Long term effects of brief Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for Psychosis. Behav. Modif. 2012, 36, 165–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaudiano, B.A.; Herbert, J.D. Acute treatment of inpatients with psychotic symptoms using Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: Pilot results. Behav. Res. Ther. 2006, 44, 415–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Overall, G.; Gorham, D. The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychol. Rep. 1962, 10, 799–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bach, P.; Gaudiano, B.A.; Hayes, S.C.; Herbert, J.D. Reduced believability of positive symptoms mediates improved hospitalization outcomes of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for psychosis. Psychos. Psychol. Soc. Integr. Approaches 2013, 5, 166–174. [Google Scholar]

- Gaudiano, B.A.; Herbert, J.D.; Hayes, S.C. Is it the symptom or the relation to it? Investigating potential mediators of change in acceptance and commitment therapy for psychosis. Behav. Ther. 2010, 41, 543–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- First, M.; Spitzer, R.; Gibbon, M.; Williams, J. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV, Research Version, Patient Edition. (SCID-I/P); Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Folstein, M.F.; Folstein, S.; McHugh, P.R. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J. Psychiatr. Res. 1975, 12, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canuso, C.M.; Pandina, G. Gender and schizophrenia. Psychopharmacol. Bull. 2007, 40, 178–190. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- National Institute of Mental Health. The Road Ahead: Research Parternships to Transform Services; Department of Health and Human Services: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2006.

- Penn, D.L.; Mueser, K.T.; Tarrier, N.; Gloege, A.; Cather, C.; Serrano, D.; Otto, M.W. Supportive therapy for schizophrenia: Possible mechanisms and implications for adjunctive psychosocial treatments. Schizophr. Bull. 2004, 30, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buckley, L.A.; Maayan, N.; Soares-Weiser, K.; Adams, C.E. Supportive therapy for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, CD004716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stip, E.; Letourneau, G. Psychotic symptoms as a continuum between normality and pathology. Can. J. Psychiatry 2009, 54, 140–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abba, N.; Chadwick, P.; Stevenson, C. Responding mindfullly to distressing psychosis: A grounded theory analysis. Psychother. Res. 2007, 18, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farhall, J.; Greenwood, K.M.; Jackson, H.J. Coping with hallucinated voices in schizophrenia: A review of self-initiated strategies and therapeutic interventions. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2007, 27, 476–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martell, C.R.; Addis, M.E.; Jacobson, N.S. Depression in Context: Strategies for Guided Action; W.W. Norton: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, S.C.; Levin, M.; Plumb, J.; Boulanger, J.; Pistorello, J. Acceptance and commitment therapy and contextual behavioral science: Examining the progress of a distinctive model of behavioral and cognitive therapy. Behav. Ther. 2013, 44, 180–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mueser, K.T.; Corrigan, P.W.; Hilton, D.W.; Tanzman, B.; Schaub, A.; Gingerich, S.; Essock, S.M.; Tarrier, N.; Morey, B.; Vogel-Scibilia, S.; et al. Illness management and recovery: A review of the research. Psychiatr. Serv. 2002, 53, 1272–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kashdan, T.B.; Barrios, V.; Forsyth, J.P.; Steger, M.F. Experiential avoidance as a generalized psychological vulnerability: Comparisons with coping and emotion regulation strategies. Behav. Res. Ther. 2006, 44, 1301–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, S.; Strosahl, K.D.; Wilson, K.; Bissett, R.; Pistorello, J.; Toarmino, D.; Polusny, M.; Dykstra, T.; Batten, S.; Bergan, J.; et al. Measuring experiential avoidance: A preliminary test of a working model. Psychol. Rec. 2004, 54, 553–578. [Google Scholar]

- Tull, M.T.; Gratz, K.L.; Salters, K.; Roemer, L. The role of experiential avoidance in posttraumatic stress symptoms and symptoms of depression, anxiety, and somatization. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2004, 192, 754–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shawyer, F.; Ratcliff, K.; Mackinnon, A.; Farhall, J.; Hayes, S.C.; Copolov, D. The voices acceptance and action scale (VAAS): Pilot data. J. Clin. Psychol. 2007, 63, 593–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Udachina, A.; Thewissen, V.; Myin-Germeys, I.; Fitzpatrick, S.; O’Kane, A.; Bentall, R.P. Understanding the relationships between self-esteem, experiential avoidance, and paranoia: Structural equation modelling and experience sampling studies. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2009, 197, 661–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldstone, E.; Farhall, J.; Ong, B. Life hassles, experiential avoidance and distressing delusional experiences. Behav. Res. Ther. 2011, 49, 260–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villatte, M.; Monestes, J.L.; McHugh, L.; Freixa i Baque, E.; Loas, G. Adopting the perspective of another in belief attribution: Contribution of Relational Frame Theory to the understanding of impairments in schizophrenia. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry 2010, 41, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beevers, C.G.; Keitner, G.I.; Ryan, C.E.; Miller, I.W. Cognitive predictors of symptom return following depression treatment. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2003, 112, 488–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beevers, C.G.; Miller, I.W. Perfectionism, cognitive bias, and hopelessness as prospective predictors of suicidal ideation. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 2004, 34, 126–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beevers, C.G.; Miller, I.W. Unlinking negative cognition and symptoms of depression: Evidence of a specific treatment effect for cognitive therapy. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2005, 73, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garety, P.A.; Freeman, D.; Jolley, S.; Dunn, G.; Bebbington, P.E.; Fowler, D.G.; Kuipers, E.; Dudley, R. Reasoning, emotions, and delusional conviction in psychosis. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2005, 114, 373–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Purdon, C. Thought suppression and psychopathology. Behav. Res. Ther. 1999, 37, 1029–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rassin, E.; Merckelbach, H.; Muris, P. Paradoxical and less paradoxical effects of thought suppression: A critical review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2000, 20, 973–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegner, D.M. Ironic processes of mental control. Psychol. Rev. 1994, 101, 34–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wenzlaff, R.M.; Bates, D.E. Unmasking a cognitive vulnerability to depression: How lapses in mental control reveal depressive thinking. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 75, 1559–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tait, L.; Birchwood, M.; Trower, P. Predicting engagement with services for psychosis: Insight, symptoms and recovery style. Br. J. Psychiatry 2003, 182, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tait, L.; Birchwood, M.; Trower, P. Adapting to the challenge of psychosis: Personal resilience and the use of sealing-over (avoidant) coping strategies. Br. J. Psychiatry 2004, 185, 410–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shonin, E.; Van Gordon, W.; Griffiths, M.D. Do mindfulness-based therapies have a role in the treatment of psychosis? Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2014, 48, 124–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaudiano, B.A. Brief acceptance and commitment therapy for the acute treatment of hospitalized patients with psychosis. In CBT for Schizophrenia: Evidence Based Interventions and Future Directions; Steel, C., Ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2013; pp. 191–212. [Google Scholar]

- Pollard, S. Measuring Treatment Fidelity in Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for Psychosis. Unpublished Master of Clinical Psychology Thesis, School of Psychological Science, La Trobe University, Melbourne Australia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- McGrath, K.B.; Forman, E.M.; Ddel Mar Cabiya, M.; Hoffman, K.L.; Marques, K.; Moritra, E.; Zabell, J.A. Development and validation of the Drexel University ACT/CBT Therapist Adherence Rating Scale. In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Association for Behavior and Cognitive Therapies, Washington, DC, USA, November 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Shafer, A. Meta-analysis of the brief psychiatric rating scale factor structure. Psychol. Assess. 2005, 17, 324–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ventura, J.; Lukoff, D.; Nuechterien, K.; Liberman, R.P.; Green, M.F.; Shaner, A. Brief psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS): Expanded Version, Ver. 4.0; UCLA Department of Psychiatry and Biobehavioral Sciences: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Barkham, M.; Evans, C.; Margison, F.; McGrath, G.; Mellor-Clark, J.; Milne, D.; Connell, J. The rationale for developing and implementing core batteries in service settings and psychotherapy outcome research. J. Ment. Health 1998, 7, 35–47. [Google Scholar]

- Bilker, W.; Brensinger, C.; Kurtz, M.; Kohler, C.; Gur, R.; Siegel, S.; Gur, R. Development of an abbreviated schizophrenia quality of life scale using a new method. Neuropsychopharmacology 2003, 28, 773–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Federici, S.; Meloni, F.; Mancini, A.; Lauriola, M.; Olivetti Belardinelli, M. World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule II: Contribution to the Italian validation. Disabil. Rehabil. 2009, 31, 553–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyer, L.; Simeoni, M.; Loundou, A.; D’Amato, T.; Reine, G.; Lancon, C.; Auquier, P. The development of the S-QoL 18: A shortened quality of life questionnaire for patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 2010, 121, 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byerly, M.J.; Nakonezny, P.A.; Rush, A.J. The Brief Adherence Rating Scale (BARS) validated against electronic monitoring in assessing the antipsychotic medication adherence of outpatients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Schizophr. Res. 2008, 100, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linehan, M.M.; Heard, H.L. Treatment History Interview (THI); University of Washington: Seattle, WA, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Bond, F.W.; Hayes, S.C.; Baer, R.A.; Carpenter, K.M.; Guenole, N.; Orcutt, H.K.; Waltz, T.; Zettle, R.D. Preliminary psychometric properties of the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-II: A revised measure of psychological flexibility and experiential avoidance. Behav. Ther. 2011, 42, 676–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, K.G.; Sandoz, E.K.; Kitchens, J.; Roberts, M.E. The Valued Living Questionnaire: Defining and measuring valued action within a behavioral framework. Psychol. Rec. 2010, 60, 249–272. [Google Scholar]

- Larsen, D.; Attkisson, C.; Hargreaves, W.; Nguyen, T. Assessment of client/patient satisfaction: Development of a general scale. Eval. Program Plan. 1979, 2, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraemer, H.C.; Mintz, J.; Noda, A.; Tinklenberg, J.; Yesavage, J.A. Caution regarding the use of pilot studies to guide power calculations for study proposals. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2006, 63, 484–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraemer, H.C.; Kupfer, D.J. Size of treatment effects and their importance to clinical research and practice. Biol. Psychiatry 2006, 59, 990–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szymanski, S.R.; Cannon, T.D.; Gallacher, F.; Erwin, R.J.; Gur, R.E. Course of treatment response in first-episode and chronic schizophrenia. Am. J. Psychiatry 1996, 153, 519–525. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Leucht, S.; Engel, R.R. The relative sensitivity of the Clinical Global Impressions Scale and the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale in antipsychotic drug trials. Neuropsychopharmacology 2006, 31, 406–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emsley, R.; Rabinowitz, J.; Medori, R. Time course for antipsychotic treatment response in first-episode schizophrenia. Am. J. Psychiatry 2006, 163, 743–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leucht, S.; Davis, J.M.; Engel, R.R.; Kane, J.M.; Wagenpfeil, S. Defining ‘response’ in antipsychotic drug trials: Recommendations for the use of scale-derived cutoffs. Neuropsychopharmacology 2007, 32, 1903–1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hedeker, D. Generalized linear mixed models. In Encyclopedia of Statistics in Behavioral Sciences; Everitt, B.S., Howell, D.C., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon, D.P.; Fritz, M.S.; Williams, J.; Lockwood, C.M. Distribution of the product confidence limits for the indirect effect: Program PRODCLIN. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 384–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Measure | Construct Assessed | Method | Time Points |

|---|---|---|---|

| Screening and Diagnosis | |||

| Mini-Mental state Exam (MMSE) [49] | Cognitive impairment | Interviewer | BL |

| Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) [48] | Axis I diagnosis | Interviewer | BL |

| Psychiatric Symptoms | |||

| Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) [45,82] | Psychiatric symptoms | Interviewer | BL,DC,4 |

| Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation (CORE) [83] | Psychiatric symptoms | Self-Report | BL,DC,4 |

| Functioning | |||

| Heinrichs Brief Quality of Life Scale [84] | Quality of Life | Interviewer | BL,DC,4 |

| WHO Disability Assessment Schedule (WHODAS)-12 [85] | Psychosocial Functioning | Self-Report | BL,DC,4 |

| Schizophrenia-Quality of Life-18 (S-QOL-18) [86] | Quality of Life | Self-Report | BL,DC,4 |

| Treatment Adherence/Utilization | |||

| Brief Adherence Rating Scale (BARS) [87] | Medication adherence | Interviewer | 4 |

| Treatment History Interview-4 (THI-4) [88] | Treatment utilization | Interviewer | 4 |

| Mechanisms Measures | |||

| Cognitive and Affective Mindfulness Scale-Revised | Mindfulness | Self-report | BL,DC,4 |

| Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-II (AAQ-II) [61,89] | Psychological acceptance | Self-report | BL,DC,4 |

| Valuing Questionnaire (VQ) [90] | Values-consistent living | Self-report | BL,DC,4 |

| Acceptability/Satisfaction | |||

| Client Satisfaction Questionnaire-8 (CSQ-8) [91] | Treatment satisfaction | Self-report | DC |

| Qualitative Post-Treatment Interview | Treatment satisfaction | Interview | DC |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gaudiano, B.A.; Davis, C.H.; Epstein-Lubow, G.; Johnson, J.E.; Mueser, K.T.; Miller, I.W. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for Inpatients with Psychosis (the REACH Study): Protocol for Treatment Development and Pilot Testing. Healthcare 2017, 5, 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare5020023

Gaudiano BA, Davis CH, Epstein-Lubow G, Johnson JE, Mueser KT, Miller IW. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for Inpatients with Psychosis (the REACH Study): Protocol for Treatment Development and Pilot Testing. Healthcare. 2017; 5(2):23. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare5020023

Chicago/Turabian StyleGaudiano, Brandon A., Carter H. Davis, Gary Epstein-Lubow, Jennifer E. Johnson, Kim T. Mueser, and Ivan W. Miller. 2017. "Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for Inpatients with Psychosis (the REACH Study): Protocol for Treatment Development and Pilot Testing" Healthcare 5, no. 2: 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare5020023