Cross-National Differences in Psychosocial Factors of Perinatal Depression: A Systematic Review of India and Japan

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategies

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Review Process

3. Results

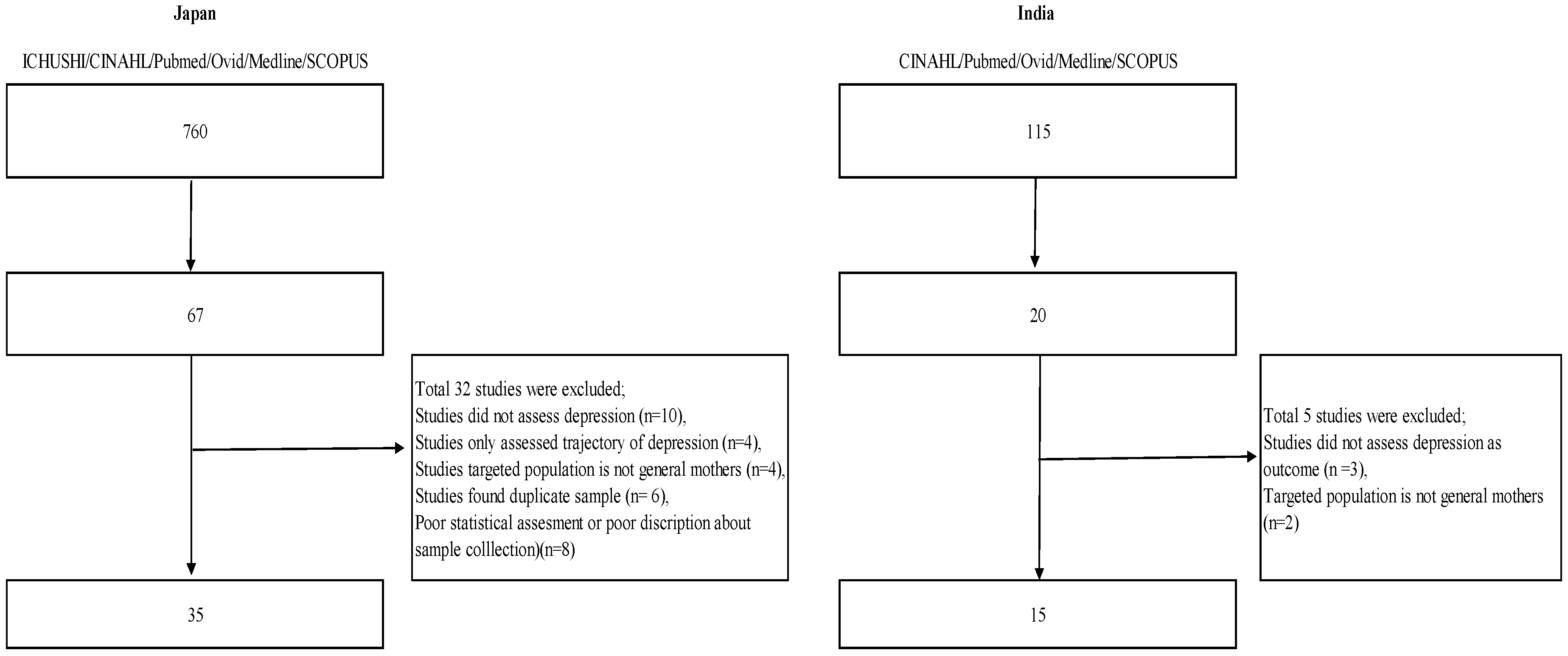

3.1. Article Extraction

3.2. Prevalence and Common Factors

3.3. Common Factors

3.4. Factors Identified Differently between the Two Countries

4. Discussion

4.1. The Prevalence of Antenatal and Postnatal Depression

4.2. Common Factors

4.3. Interpersonal Characteristics in the Cultural Contexts of Asian Countries

4.4. Interpersonal Factors in India and Japan

4.5. Preference of Male Infants, and Lower Socio-Economic Status in India

4.6. Implications for Clinical Practice and Suggestions for Future Study

4.7. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gavin, N.I.; Gaynes, B.N.; Lohr, K.N.; Meltzer-Brody, S.; Gartlehner, G.; Swinson, T. Perinatal depression: A systematic review of prevalence and incidence. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2005, 106, 1071–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Orsolini, L.; Valchera, A.; Vecchiotti, R.; Tomasetti, C.; Lasevoli, F.; Fornaro, M.; De Berardis, D.; Perna, G.; Pompili, M.; Bellantuono, C. Suicide during perinatal period: Epidemiology, risk factors, and clinical correlates. Front. Psychiatry 2016, 7, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klainin, P.; Arthur, D.G. Postpartum depression in Asian cultures: A literature review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2009, 46, 1355–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norhayati, M.N.; Hazlina, N.H.; Asrenee, A.R.; Emilin, W.M. Magnitude and risk factors for postpartum symptoms: A literature review. J. Affect. Disord. 2015, 175, 34–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biaggi, A.; Conroy, S.; Pawlby, S.; Pariante, C.M. Identifying the women at risk of antenatal anxiety and depression: A systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 2016, 191, 62–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwata, H.; Mori, E.; Tsuchiya, M.; Sakajo, A.; Maehara, K.; Ozawa, H.; Morita, A.; Maekawa, T.; Aoki, K.; Tamakoshi, K. Predictors of depressive symptoms in older Japanese primiparas at 1 month post-partum: A risk-stratified analysis. Jpn. J. Nurs. Sci. 2016, 13, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otake, Y.; Nakajima, S.; Uno, A.; Kato, S.; Sasaki, S.; Yoshioka, E.; Ikeno, T.; Kishi, R. Association between maternal antenatal depression and infant development: A hospital-based prospective cohort study. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2014, 19, 30–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitamura, T.; Yoshida, K.; Okano, T.; Kinoshita, K.; Hayashi, M.; Toyoda, N.; Ito, M.; Kudo, N.; Tada, K.; Kanazawa, K.; et al. Multicentre prospective study of perinatal depression in Japan: Incidence and correlates of antenatal and postnatal depression. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2006, 9, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, V.; Rodrigues, V.; DeSouza, N. Gender, poverty, and postnatal depression: A study of mothers in Goa, India. Am. J. Psychiatry 2002, 159, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The World Bank. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.DYN.TFRT.IN/ (accessed on 5 April 2017).

- Chandra, P.S.; Venkatasubramanian, G.; Thomas, T. Infanticidal ideas and infanticidal behavior in Indian women with severe postpartum psychiatric disorders. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2002, 190, 457–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shivalli, S.; Gururaj, N. Postnatal depression among rural women in South India: Do socio-demographic, obstetric and pregnancy outcome have a role to play? PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0122079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzumiya, H.; Yamashita, H.; Yoshida, K. Hokenkikan ga jisshi suru boshihoumon taishousha no sango utu byou zenkoku tashisetu chousa. Kousei no Shihyou 2004, 51, 1–5. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Vandenbroucke, J.P.; von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Pocock, S.J.; Poole, C.; Schlesselman, J.J.; Egger, M.; STROBE Initiative. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): Explanation and elaboration. Epidemiology 2007, 18, 805–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheela, C.N.; Venkatesh, S. Screening for postnatal depression in a tertiary care hospital. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. India 2016, 66, 72–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodhare, T.N.; Sethi, P.; Bele, S.D.; Gayatri, D.; Vivekanand, A. Postnatal quality of life, depressive symptoms, and social support among women in southern India. Women Health 2015, 55, 353–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, A.; Tyagi, P.; Kaur, P.; Puliyel, J.; Sreenivas, V. Association of birth of girls with postnatal depression and exclusive breastfeeding: An observational study. BMJ Open 2014, 4, e003545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srinivasan, N.; Murthy, S.; Singh, A.K.; Upadhyay, V.; Mohan, S.K.; Joshi, A. Assessment of burden of depression during pregnancy among pregnant women residing in rural setting of Chennai. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2015, 9, LC08–LC12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, A.R.; Edwin, S.; Joachim, N.; Mathew, G.; Ajay, S.; Joseph, B. Postnatal depression among women availing maternal health services in a rural hospital in South India. Pak. J. Med. Sci. 2015, 31, 408–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nongrum, R.; Thomas, E.; Lionel, J.; Jacob, K.S. Domestic violence as a risk factor for maternal depression and neonatal outcomes: A hospital-based cohort study. Indian J. Psychol. Med. 2014, 36, 179–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukose, A.; Ramthal, A.; Thomas, T.; Bosch, R.; Kurpad, A.V.; Duggan, C.; Srinivasan, K. Nutritional factors associated with antenatal depressive symptoms in the early stage of pregnancy among urban South Indian women. Matern. Child Health J. 2014, 18, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prost, A.; Lakshminarayana, R.; Nair, N.; Tripathy, P.; Copas, A.; Mahapatra, R.; Rash, S.; Gope, R.K.; Rath, S.; Bajpai, A.; et al. Predictors of maternal psychological distress in rural India: A cross-sectional community based study. J. Affect. Disord. 2012, 138, 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubey, C.; Gupta, N.; Bhasin, S.; Muthal, R.A.; Arora, R. Prevalence and associated risk factors for postpartum depression in women attending a tertiary hospital, Delhi, India. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2012, 58, 577–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savarimuthu, R.J.; Ezhilarasu, P.; Charles, H.; Antonisamy, B.; Kurian, S.; Jacob, K.S. Post-partum depression in the community: A qualitative study from rural South India. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2010, 56, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varma, D.; Chandra, P.S.; Thomas, T. Intimate partner violence and sexual coercion among pregnant women in India: Relationship with depression and post-traumatic stress disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 2007, 102, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, M.; Patel, V.; Jaswal, S.; de Souza, N. Listening to mothers: Qualitative studies on motherhood and depression from Goa, India. Soc. Sci. Med. 2003, 57, 1797–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandran, M.; Tharyan, P.; Muliyil, J.; Abraham, S. Post-partum depression in a cohort of women from a rural area of Tamil Nadu, India. Incidence and risk factors. Br. J. Psychiatry 2002, 181, 499–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kita, S.; Haruna, M.; Matsuzaki, M.; Kamibeppu, K. Associations between intimate partner violence (IPV) during pregnancy, mother-to-infant bonding failure, and postnatal depressive symptoms. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2016, 19, 623–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tachibana, Y.; Koizumi, T.; Takehara, K.; Kakee, N.; Tsujii, H.; Mori, R.; Inoue, E.; Ota, E.; Yoshida, K.; Kasai, K.; et al. Antenatal risk factors of postpartum depression at 20 weeks gestation in a Japanese sample: Psychosocial perspectives from a cohort study in Tokyo. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0142410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shirakata, M.; Tanaka, Y.; Souke, K.; Okuyama, Y.; Fujii, H.; Takada, M.; Sawa, R.; Ebina, A.; Kondo, Y.; Ono, R. Ninshinki no yotu to nyou shikkin, utsubyou tono kanren. Hyogo J. Matern. Health 2014, 23, 20–22. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Fukao, S.; Kabeyama, K. Association between depressive tendency and stress-coping ability of pregnant and postpartum women following assisted reproductive technology and conventional infertility treatment: A longitudinal survey from late pregnancy to 1 month postpartum. Jpn. Acad. Midwifery 2014, 28, 260–267. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amagai, S.; Emori, Y.; Murai, F.; Koizumi, J. Depression and life satisfaction in pregnant women: Associations with socio-economic status. Boseieisei 2014, 55, 387–395. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Minatani, M.; Kita, S.; Ohashi, Y.; Kitamura, T.; Haruna, M.; Sakanashi, K.; Tanaka, T. Temperament, character, and depressive symptoms during pregnancy: A Study of a Japanese population. Depres. Res. Treat. 2013, 140169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinjo, H.; Yuge, M.; Kawasaki, K.; Takeo, K.; Kishi, K.; Lertsakornsiri, M.; Maleewan, L.; Takahashi, C.; Maruyama, Y. Comparative study on depression and related factors among pregnant and postpartum women in Japan and Thailand. Sakudaigaku Kango Kenkyu Zasshi 2013, 5, 5–19. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Sugawara, S.; Ohira, H. The relationship between sense of coherence and mental health during the perinatal period. J. Child Health 2013, 72, 17–27. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urayama, A.; Nagayama, K.; Ooki, H. Ninshincyu no jisonkanjyoutokuseitekijikokouryokukan tosango yokuutu tono kanrensei. Parinatal Care 2013, 32, 617–623. [Google Scholar]

- Sugishita, Y.; Kamibeppu, K. Relationship between Prepartum and postpartum depression to use EPDS. Bosei Eisei 2013, 53, 444–450. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto, M. Mental health during pregnancy (part 1)—The correlation of depressive schemas with depressed mood in pregnant women. Boseieisei 2012, 52, 546–553. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Nagasaka, I.; Sano, S. Research into factors during pregnancy for predicting postpartum depression: From the viewpoint of prevention of child abuse. J. Child Health 2012, 71, 737–747. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Hayakawa, N.; Koide, T.; Okada, T.; Murase, S.; Aleksic, B.; Furumura, K.; Shiino, T.; Nakamura, Y.; Tamaji, A.; Ishikawa, N.; et al. The postpartum depressive state in relation to perceived rearing: A prospective cohort study. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e50220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kokubu, M.; Okano, T.; Sugiyama, T. Postnatal depression, maternal bonding failure, and negative attitudes towards pregnancy: A longitudinal study of pregnant women in Japan. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2012, 15, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinjo, H.; Kawasaki, K.; Takeo, K.; Yuge, M.; Maruyama, Y.; Kishi, K. Depression symptoms and related factors on pregnant and postpartum women in Japan. Sakudaigaku Kango Kenkyu Zasshi 2012, 3, 15–25. [Google Scholar]

- Mori, T.; Tsuchiya, K.; Matsumoto, K.; Suzuki, K.; Mori, N.; Takei, N. Psychosocial risk factors for postpartum depression and their relation to timing of onset: The Hamamatsu Birth Cohort (HBC) Study. J. Affect. Disord. 2011, 135, 341–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyake, Y.; Tanaka, K.; Sasaki, S.; Hirota, Y. Employment, income, and education and risk of postpartum depression: The Osaka Maternal and Child Health Study. J. Affect. Disord. 2011, 130, 133–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kikuchi, K.; Tomotake, M.; Iga, J.; Ueno, S.; Kahara, M.; Omori, T. Psychological features of pregnant women predisposing to depressive state during the perinatal period. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2010, 39, 1459–1468. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Iwamoto, S.; Nakamura, M.; Yamashita, H.; Yoshida, K. Impact of situation of pregnancy on depressive symptom of women in perinatal period. J. Natl. Inst. Public Health 2010, 59, 51–59. [Google Scholar]

- Arai, Y.; Takahashi, M. Family functioning and postpartum depression in women at one month postpartum. Kitasato Int. J. Nurs. Sci. 2009, 11, 1–9. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Ando, T.; Muto, T. The course of depression from pregnancy through one year postpartum: Predictors and moderators. Jpn. J. Dev. Psychol. 2008, 23, 283–293. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Sato, A.; Kitamiya, C.; Kudo, H.; Watanabe, M.; Menzawa, K.; Sasaki, H. Factors associated with late post-partum depression in Japan. Jpn. J. Nurs. Sci. 2009, 6, 27–36. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanazawa, R.; Narita, K.; Takahashi, H.; Kubato, C.; Yamada, A.; Godaigi, A.; Saga, M.; Akashi, Y. Edinburgh sango utubyou jikohyoukahyou kou tokutensha ni kyoutu suru haikei. Akita Nouson ikai shi 2008, 54, 30–34. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Endo, K.; Nishiwaki, M.; Yamakawa, Y.; Komatsu, R.; Hori, M.; Tutumi, K.; Misawa, K.; Kawasaki, K. Predictors of postpartum depression in the early postpartum stage. Yamagata Hoken Iryou Kenkyu 2008, 11, 1–8. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Mitamura, T.; Satou, H.; Mizukami, N. Risk factors of postpartum depression in low risk pregnant women. J. Jpn. Soc. Perinat. Neonatal Med. 2008, 44, 68–73. [Google Scholar]

- Sekizuka, M.; Sakai, A.; Shimada, K.; Tabuchi, N.; Kameda, Y. Relationship between stress coping ability and the degree of satisfaction with delivery or postpartum depression tendency. Boseieisei 2017, 48, 106–113. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Sato, N.; Morioka, Y.; Sato, A.; Oiji, A.; Murata, A. Relationships among mother’s postpartum emotional state, her own attachment style and attachment formation toward her baby. Boseieisei 2006, 47, 320–329. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Ninagawa, E.; Yamamoto, K.; Kawaguchi, N.; Tohi, T.; Yoshida, H.; Morinaga, H.; Kato, K.; Matsui, Y.; Nagamori, M.; Saito, M.; et al. Study on the Maternal Mental Health after Childbirth. Hokuriku J. Public Health 2005, 32, 45–48. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Tokiwa, Y. Relationship between self-evaluation of child birth experience and early postpartum depression. J. Jpn. Acad. Midwifery 2003, 17, 27–38. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwatani, S.; Hokutou, H.; Wakabayashi, N.; Yoshikawa, T.; Naruse, E. The relation among the mental states at the early stage of pregnancy. J. Jpn. Soc. Psychosomatic Obstet. Gynaecol. 2001, 6, 116–123. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamaki, R.; Murata, M.; Okano, T. Risk factors for postpartum depression in Japan. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 1997, 51, 93–98. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, J.L.; Holden, J.M.; Sagovsky, R. Detection of postnatal depression: Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br. J. Psychiatry 1987, 150, 782–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B.W. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Int. Med. 2001, 16, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, R.C.; Andrews, G.; Colpe, L.; Hiripi, E.; Mroczek, D.K.; Normand, S.L.; Walters, E.E.; Zaslavsky, A.M. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol. Med. 2002, 32, 959–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, C.T. The effects of postpartum depression on child development: A meta-analysis. Arch. Psychiatry Nurs. 1998, 12, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, G.; Pelosi, A.J.; Araya, R.; Dunn, G. Measuring psychiatric disorder in the community: A standardized assessment for use by lay interviewers. Psychol. Med. 1992, 22, 465–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zung, W.W. A self-rating depression scale. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1965, 12, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zigmond, A.S.; Snaith, R.P. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1983, 67, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radloff, L.S. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 1977, 1, 385–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- First, M.B.; Spitzer, R.L.; Gibbon, M.; Williams, J.B.W. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Patient Edition. (SCID-I/P); Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, M.C.; Srinivasan, K.; Stein, A.L.; Menezes, G.; Sumithra, R.; Ramchandani, P.G. Assessing prenatal depression in the rural developing world: A comparison of two screening measures. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2011, 14, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faisal-Cury, A.; Menezes, P.; Araya, R.; Zugaib, M. Common mental disorders during pregnancy: Prevalence and associated factors among low-income women in São Paulo, Brazil. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2009, 12, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golbasi, Z.; Kelleci, M.; Kisacik, G.; Cetin, A. Prevalence and correlates of depression in pregnancy among Turkish women. Matern. Child Health J. 2010, 14, 485–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okano, T.; Murata, M.; Masuji, S.; Tamaki, R.; Nomura, J.; Miyaoka, H.; Kitamura, T. Validity and reliability of Japanese Version of the EPDS (Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale). Arch. Psych. Diagn. Clin. Eval. 1996, 7, 525–533. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Kitamura, T.; Shima, S.; Sugawara, M.; Toda, M.A. Temporal variation of validity of self-rating questionnaires: Repeated use of the General Health Questionnaire and Zung’s Self-rating Depression Scale among women during antenatal and postnatal periods. Acta Psychiatry Scand. 1994, 90, 446–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitayama, S.; Markus, H.R.; Matsumoto, H.; Norasakkunkit, V. Individual and collective processes in the construction of the self: Self-enhancement in the United States and self-criticism in Japan. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1997, 72, 1245–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corbett, C.A.; Callister, L.C. Giving birth: The voices of women in Tamil Nadu, India. MCN Am. J. Matern. Child Nurs. 2012, 37, 298–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harada, N. Statistical analysis of risk factors for depression of mothers with a high score on Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. J. Health Sci. 2008, 5, 1–12. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Minami, T.; Ohara, T.; Muto, Y. Childbirth and childcare for mother: Focus of experience of ‘Childbirth Satogaeri’. J. Home Econ. Jpn. 2006, 57, 807–817. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama, M.; Ikeda, Y. Relationship between interpersonal conflicts and personality traits in friendship between mothers rearing little children. Jpn. J. Pers. 2013, 22, 285–288. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Labor and Health. 2016. Available online: http://www.mhlw.go.jp/file/05-Shingikai-11201000-Roudoukijunkyoku-Soumuka/0000118655.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2017).

- Xie, R.H.; He, G.; Koszycki, D.; Walker, M.; Wen, S.W. Fetal sex, social support, and postpartum depression. Can. J. Psychiatry 2009, 54, 750–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moriizumi, R. An empirical study of sex preferences for children in Japan. J. Popul. Probl. 2008, 64, 1–20. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). Available online: http://www.oecd.org/eco/surveys/INDIA-2017-OECD-economic-survey-overview.pdf (accessed on 30 November 2017).

- Kowal, P.; Afshar, S. Health and the Indian caste system. Lancet 2015, 385, 415–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shidhaye, R.; Lyngdoh, T.; Murhar, V.; Samudre, S.; Krafft, T. Predictors, help-seeking behaviour and treatment coverage for depression in adults in Sehore district, India. Br. J. Psychiatry Open 2017, 3, 212–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Austin, M.P.; Frilingos, M.; Lumley, J.; Hadzi-Pavlovic, D.; Roncolato, W.; Acand, S.; Saint, K.; Segal, N.; Parker, G. Brief antenatal cognitive behaviour therapy group intervention for the prevention of postnatal depression and anxiety: A randomized controlled trial. J. Affect. Disord. 2008, 105, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brugha, T.S.; Morrell, C.J.; Slade, P.; Walters, S.J. Universal prevention of depression in women postnatally: Cluster randomized trial evidence in primary care. Psychol. Med. 2011, 41, 739–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zlotnick, C.T.; Miller, I.W.; Pearlstein, T.; Howard, M.; Sweeney, P. A preventive intervention for pregnant women on public assistance at risk for postpartum depression. Am. J. Psychiatry 2006, 163, 1443–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weissman, M.M.; Markowitz, J.C.; Klerman, G. Comprehensive Guide to Interpersonal Psychotherapy; Basic Books: NewYork, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- White, R.G.; Sashidharan, S.P. Towards a more nuanced global mental health. Br. J. Psychiatry 2014, 204, 415–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, S.; Orr, D.M. Ethnographic perspectives on global mental health. Transcult. Psychiatry 2016, 53, 685–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assari, S. Cross-country variation in additive effects of socio-economics, health behaviors, and comorbidities on subjective health of patients with diabetes. J. Diabetes Metab. Disord. 2014, 13, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Article Number | Author | Language | Study Design | Time Frame | Sample Size | Outcome Measurements | Prevalence (Antenatal) | Prevalence (Postnatal) | Factors of Antenatal Depression | Factors of Postnatal Depression |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I1 | Sheela & Vankatesh (2016) [16] | English | Cross sectional | Between 4–7 weeks postpartum | 1600 (analysed: 1600) | EPDS (≥13) | NA | 7% | NA | Delayed breastfeeding, female infant |

| I2 | Bodhare et al., (2015) [17] | English | Cross sectional | Between 6-8 weeks postpartum | 287 (analysed: 274) | PHQ-9 | NA | 40% | NA | Teenagers, poor education, poor socioeconomic status, depressive symptoms |

| I3 | Jain et al., (2015) [18] | English | Cross sectional | Within 2 days postpartum | 1537 (analysed: unknown) | EPDS | NA | NA | NA | Mixed breast feeding |

| I4 | Shivalli & Gururaj. (2015) [13] | English | Cross sectional | Between 4 and 6 weeks postpartum | 118 (analysed: 102) | EPDS (≥13) | NA | 65% | NA | Poor socioeconomic status (below poverty line), female baby, complication of pregnancy |

| I5 | Srinivasan et al., (2015) [19] | English | Cross sectional | During pregnancy | 100 (analysed: 100) | EPDS (≥13) | NA | 26% | First trimester, idealistic distortion, partner’s history of depression | NA |

| I6 | Johnson et al., (2015) [20] | English | Cross sectional | Within 6-8 weeks postpartum | 123 (analysed: 123) | EPDS (≥12) | NA | 46% | NA | Depressed mood during pregnancy, staying only with husband, lower self esteem |

| I7 | Nongrum et al., (2014) [21] | English | Longitudinal | T1: During pregnancy, T2: After delivery | 150 (analysed: 132) | EPDS (≥12) | NA | NA | NA | Domestic violence |

| I8 | Lukose et al., (2014) [22] | English | Cross sectional | 12 weeks of pregnancy | 366 (anallysed: 366) | K-10 ≥ 6 | 33% | NA | Antenatal depression: Having nausea, vomitting, anemia. | NA |

| I9 | Prost et al., (2012) [23] | English | Cross sectional | 6 weeks after delivery | 5801 | K10 scores > 15 | NA | 12% | NA | Younger age or older age, assetqualities, health problem during pregnancy, health problem during delivery, health problem during postnatal period, alcohol consumption during pregnancy, unwanted pregnancy of father |

| I10 | Dubey et al., (2011) [24] | English | Cross sectional | T1: 34 weeks of pregnancy, T2: Within 7 days postpartum | T1: 213 T2: 293 (analysed: 506) | EPDS (≥10) | NA | 6% | NA | Family structure, socioeconomic status, marital status, female baby |

| I11 | Savarimuthu et al., (2010) [25] | English | Cross sectional | Between 2 and 4 weeks postpartum | 137 (analysed: 137) | EPDS (≥12) | NA | 26% | NA | Teenagers or older age (>30), education less than 6 years, family history of depression, thought of aborting current pregnancy, unhappy mariage reported, alcohol consumption of husband, delivery of girl |

| I12 | Varma et al., (2007) [26] | English | Cross sectional | During pregnancy | 203 (analysed: unknown) | BDI | NA | NA | A history of sexual coercion, lower life satisfaction | NA |

| I13 | Rodorigues et al., (2003) [27] | English | Qualitative | 6–8 weeks postpartum | 39 (analysed: unknown) | EPDS (≥12) | NA | NA | NA | Unemployment |

| I14 | Patel et al., (2002) [10] | English | Longitudinal | T1: 6-8 weeks postpartum, T2: 6 month postpartum | 252 (analysed: 252) | EPDS (≥12) | NA | T1:23% T2: 8% | NA | Antenatal psychiatric morbidity, unplanned pregnancy |

| I15 | Chandran et al., (2002) [28] | English | Longitudinal | T1: 34 weeks of pregnancy, T2: 6 weeks after delivery | 384 (analysed: 354) | CIS-R (structured interview) | T1:16% | T2:19% | NA | Delivery of female infant, poor support, lower income (<1001 rupees), problems with in laws, poor relationship with parents, nagative life event in previous year |

| Article Number | Author | Language | Design | Time Frame | Sample Size | Outcome Measurements | Prevalence (Antenatal) | Prevalence (Postnatal) | Factors of Antenatal Depression | Factors of Postnatal Depression |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J1 | Kita et al., (2016) [29] | English | Longitudinal | T1: Late pregnancy T2: One month postpartum | T1: 832 T2: 610 (analysed: 562) | HADS | NA | NA | Antenatal intimate partner violence | NA |

| J2 | Iwata et al., (2016) [7] | English | Longitudinal | T1: Within a few days after childbirth T2: One month postpartum | T1–T2: 479 (analysed: 455) | EPDS (≥9) | NA | T1: 21% T2: 21% | NA | Depression early postpartum, financial burden, dissatisfaction with appraisal support, physical burden in daily life, concerns about child rearing |

| J3 | Tachibana et al., (2015) [30] | English | Longitudinal | T1: 20 weeks of gestation T2: Within a few days after childbirth T3: One month postpartum | T1: 1717 T2: 1335 T3: 1383 (analysed: 1133) | EPDS (≥9) | NA | T1: 41% | NA | High EPDS score during pregnancy, a perceived lack of family cohesion, primipara, current physical illness treatment |

| J4 | Otake et al., (2015) [8] | English | Longitudinal | T1: 25–35 weeks of pregnancy T2: 1–4 months postpartum T3: 6 months postpartum | T1: 309 T2: 267 T3: 154 (analysed: 154) | EPDS (≥9) | T1: 5% | T2: 13% | Past depressive symptoms, worrying, obsessivene character | NA |

| J5 | Shirakata et al., (2014) [31] | Japanese | Cross sectional | 8–12 weeks, 23–27weeks, and 35–40 gestational weeks of pregnancy | 658 (analysed: 352) | CES-D | NA | NA | Severe back pain | NA |

| J6 | Fukao & Kabeyama. (2014) [32] | Japanese | Longitudinal | T1: Late pregnancy T2: 2–7 days postpartum T3: One month postpartum | T1–T3: 97 (analysed: 97) | EPDS (≥9) | NA | NA | Lower sense of coherence. | Lower sense of coherence |

| J7 | Amagai. (2014) [33] | Japanese | Longitudinal | T1: Late pregnancy T2: One month postpartum | T1: 264 T2: 192 (analysed:153) | EPDS (≥9) | NA | T2: 21% | NA | Financial burden, non-permanent position of partner |

| J8 | Minatani et al., (2013) [34] | English | Cross sectional | Late pregnancy | 601 (analysed: 601) | EPDS (≥9) | NA | NA | Women’s negative response towards the current pregnancy, low self-directedness and high harm avoidance, perisistence, self transcendence. | NA |

| J9 | Kinjo et al., (2013) [35] | Japanese | Cross sectional | T1: During pregnancy T2: One month postpartum | T1: 320 T2: 289 (analysed: 289) | CES-D | T1: 31% | T2: 33% | Unplanned pregnancy, financial burden | Unplanned pregnancy, financial burden, history of depression |

| J10 | Sugawara & Ohira. (2013) [36] | Japanese | Longitudinal | T1: Middle pregnancy T2: Late pregnancy T3: One month postpartum | T1–T3: 80 (analysed: 72) | EPDS (≥9) | T1: 16% T2: 12% | T3: 16% | NA | Lower sense of coherence, poor social support |

| J11 | Urayama et al., (2013) [37] | Japanese | Longitudinal | T1: Within five days postpartum T2: One month postpartum | T1: 101 T2: 101 (analysed: 100) | EPDS (≥9) | NA | T1: 33% T2: 18% | NA | Lower self efficacy, lower self esteem |

| J12 | Sugishita & Kamibeppu. (2013) [38] | Japanese | Longitudinal | T1: Late pregnancy T2: One month postpartum | T1: 161 T2: 121 (analysed:121) | EPDS (≥9) | T1: 14% | T2: 19% | NA | Antenatal depression |

| J13 | Miyamoto. (2012) [39] | Japanese | Cross sectional | During pregnancy | 128 (analysed: 128) | EPDS (≥9) | 15% | NA | Depressive schema, Intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), poor relationship with partner | NA |

| J14 | Nagasaka & Sano. (2012) [40] | Japanese | Longitudinal | T1: Early pregnancy T2: One month postpartum T3: Four month postpartum | T1: 3080 T2: 2420 T3: 2420 (analysed: 2420) | EPDS (≥9) | NA | T2: 13% T3: 12% | NA | T4: teenager, primiparas, unwanted pregnancy, poor support from husband, smoking, history of mental illness, concern about childrearing, economic concern, concern about social relations with other mothers, concern about other relative |

| J15 | Hayakawa et al., (2012) [41] | English | Longitudinal | T1: Early postpartum T2: Late pregnancy T3: One month postpartum | T1–T3: 467 (analysed: 448) | EPDS (≥9) | T2: 13.2% | NA | NA | Lower maternal care (PBI) |

| J16 | Kokubu et al., (2012) [42] | English | Longitudinal | T1: Late pregnancy T2: Early postpartum T3: One month postpartum | T1–T3: 109 (analysed: 99) | EPDS (≥9) | NA | NA | NA | Antenatal anxiety |

| J17 | Kinjo et al., (2011) [43] | Japanese | Cross sectional | T1: During pregnancy T2: One month postpartum | T1: 158 T2: 164 (analysed:164) | CES-D | T1: 30.4% | T2: 24.4% | Perceived stress, lower self esteem, poor social support | Perceived stress, lower self esteem, poor social support |

| J18 | Mori et al., (2011) [44] | English | Cross sectional | Within 4 weeks postpartum | 675 (analysed: 675) | EPDS (≥9) | NA | T1:11% | NA | Early onset depression (within 4 weeks): Lack of emotional support, psychiatric history Late onset depression (5–12 weeks): younger age(less than 25 years old), older age (older than 36 years old), history of depression |

| J19 | Miyake et al., (2011) [45] | English | Cross sectional | Between 3 and 4 months postpartum | 771 (analysed: 771) | EPDS (≥9) | NA | 14% | NA | Fulltime workers |

| J20 | Kikuchi et al., (2010) [46] | Japanese | Longitudinal | T1: Middle pregnancy T2: One month postpartum | T1: 243 T2: 163 (analysed: 113) | EPDS (≥9) | NA | 15% | NA | Personality (Neuroticism, low extravert, low agreeableness, low conciousness, emotional oriented coping style), high protection from father |

| J21 | Iwamoto et al., (2010) [47] | Japanese | Longitudinal | T1: Late pregnancy T2: 5 days postpartum T3: One month postpartum T4: 4 months postpartum | 590 (analysed: 590) | EPDS (≥9) | NA | NA | Unplanned pregnancy | Unplanned pregnancy, pregnancy by infertility treatment |

| J22 | Arai & Takahashi. (2009) [48] | Japanese | Cross sectional | One month postpartum | 283 (analysed: 149) | EPDS (≥9) | NA | 21% | NA | Overall functioning, lower affective responsiveness, lower affective involvement |

| J23 | Ando & Muto. (2009) [49] | Japanese | Longitudinal | T1: During pregnancy, T2: 5 weeks postpartum, T3: 3 months postpartum, T4: 6 months postpartum, T5: 1 year after delivery | T1-3: 522 (analysed: 407) | EPDS (≥9) | NA | NA | NA | Unwanted pregnancy, less delighted with fetal movement, morning sickness, conflict with work life balance, poor marital relationship, self absorption, lower self esteem, low attachment with others |

| J24 | Satoh et al., (2009) [50] | English | Cross sectional | 4 months postpartum | 169 (analysed: 169) | EPDS (≥9) | NA | 23% | NA | General health abnormality, poor sociability, abnormality, worry about baby care, poor cooperation of the husband |

| J25 | Kanazawa et al., (2008) [51] | Japanese | Longitudinal | T1: During pregnancy, T2: Within a few days after delivery, T3: One month postpartum | 112 (analysed: 111) | EPDS (≥9) | NA | 14% | financial burden, smoking or alcohol comsumption durin pregnancy. | Lower confidence of child rearing, perceived stress with childrearing, concern about baby’s condition |

| J26 | Endo et al., (2008) [52] | Japanese | Longitudinal | T1: 5th day postpartum T2: One month postpartum | 57 (analysed: 57) | EPDS (≥9) | NA | 30% | NA | Older age, maternity blues |

| J27 | Mitamura.(2008) [53] | Japanese | Longitudinal | T1: Within a few days after delivery T2: One month postpartum | T1: 549 T2: 503 (analysed: 503) | EPDS (≥9) | NA | 8% | NA | Teenagers, divorce during pregnancy or after delivery, history of mental illness, maternity blues |

| J28 | Sekizuka et al., (2007) [54] | Japanese | Longitudinal | T1: Late pregnancy, T2: Between 3–5 days after delivery | T1-2: 54 (analysed: 54) | SDS | NA | NA | NA | Lower sense of coherence, lower satisfaction of delivery |

| J29 | Sato et al., (2006) [55] | Japanese | Longitudinal | T1: Late pregnancy, T2: 5th day postpartum, T3: One month postpartum, T4: Three month postpartum | T1–T3: 58 (analysed: 58) | SDS | NA | NA | NA | T4: Multipara, Living with extended family, perceived negative relationship with their husband, biological mother, difficulty in baby’s treatment, lack of satisfaction from husband’s support and mother’s support, unbalanced working model, negative feeling toward the baby, negative feeling toword the baby, low maternal attachment, anxiety regarding children |

| J30 | Kitamura et al., (2006) [9] | English | Longitudinal | T1: Late pregnancy T2: One month T3: Three months postpartum | T1–T3: 303 | SCID | T1: 5% | T2: 5% | Younger age, negative attitude towards the current pregnancy | Poor accomodation, disatisfaction with child sex |

| J31 | Ninagawa et al., (2005) [56] | Japanese | Cross sectional | 2 month postpartum | 332 (analysed: 289) | EPDS (≥9) | NA | 16% | NA | Extended family household |

| J32 | Suzumiya et al., (2004) [14] | Japanese | Cross sectional | Within 3 months postpartum | 3370 (analysed: 3370) | EPDS (≥9) | NA | 14% | NA | Pregnancy anomaly, experience of seeing psychiatrist or counsellors, Previous still birth, miscarriage, experience that family has passed away, poor social support from biological parents, poor social support from others, satisfied with regidencial place, financial burden, illness of infant |

| J33 | Tokiwa.(2003) [57] | Japanese | Cross sectional | Within seven days pospartum | 1500 (analysed: 932) | EPDS (≥9) | NA | NA | NA | Negative birth experience, dissatisfaction with medical staffs, younger age, higher anxiety |

| J34 | Iwatani et al., (2001) [58] | Japanese | Longitudinal | T1: Early pregnancy T2: Five days postpartum T3: One month postpartum | T1–T2: 252 (analysed: 252) | SDS (T1 and T2) EPDS (T2) | T1: 31% | T2: 13% | Primiparas | Maternity blues |

| J35 | Tamaki et al., (1997) [59] | English | Longitudinal | T1: One month postpartum, T2: Three months postpartum T3: Four months postpartum | T1: 672 T2: 1096 T3: 822 T4: 913 (analysed: 672) | EPDS (≥9) | NA | T1: 18% T2: 12.1% T3: 6.7% | NA | T1: primiparas, worry about child care, higher anxiety, T2: negative life events, worry about childcare, higher anxiety |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Takegata, M.; Ohashi, Y.; Lazarus, A.; Kitamura, T. Cross-National Differences in Psychosocial Factors of Perinatal Depression: A Systematic Review of India and Japan. Healthcare 2017, 5, 91. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare5040091

Takegata M, Ohashi Y, Lazarus A, Kitamura T. Cross-National Differences in Psychosocial Factors of Perinatal Depression: A Systematic Review of India and Japan. Healthcare. 2017; 5(4):91. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare5040091

Chicago/Turabian StyleTakegata, Mizuki, Yukiko Ohashi, Anisha Lazarus, and Toshinori Kitamura. 2017. "Cross-National Differences in Psychosocial Factors of Perinatal Depression: A Systematic Review of India and Japan" Healthcare 5, no. 4: 91. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare5040091