A Sleep Questionnaire for Children with Severe Psychomotor Impairment (SNAKE)—Concordance with a Global Rating of Sleep Quality

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Dataset

2.2. The Sleep Questionnaire for Children with Severe Psychomotor Impairment (SNAKE)

- Disturbances going to sleep

- Disturbances remaining asleep

- Arousal and breathing disorders

- Daytime sleepiness

- Daytime behavior disorders

2.3. Global Rating of Sleep Quality

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

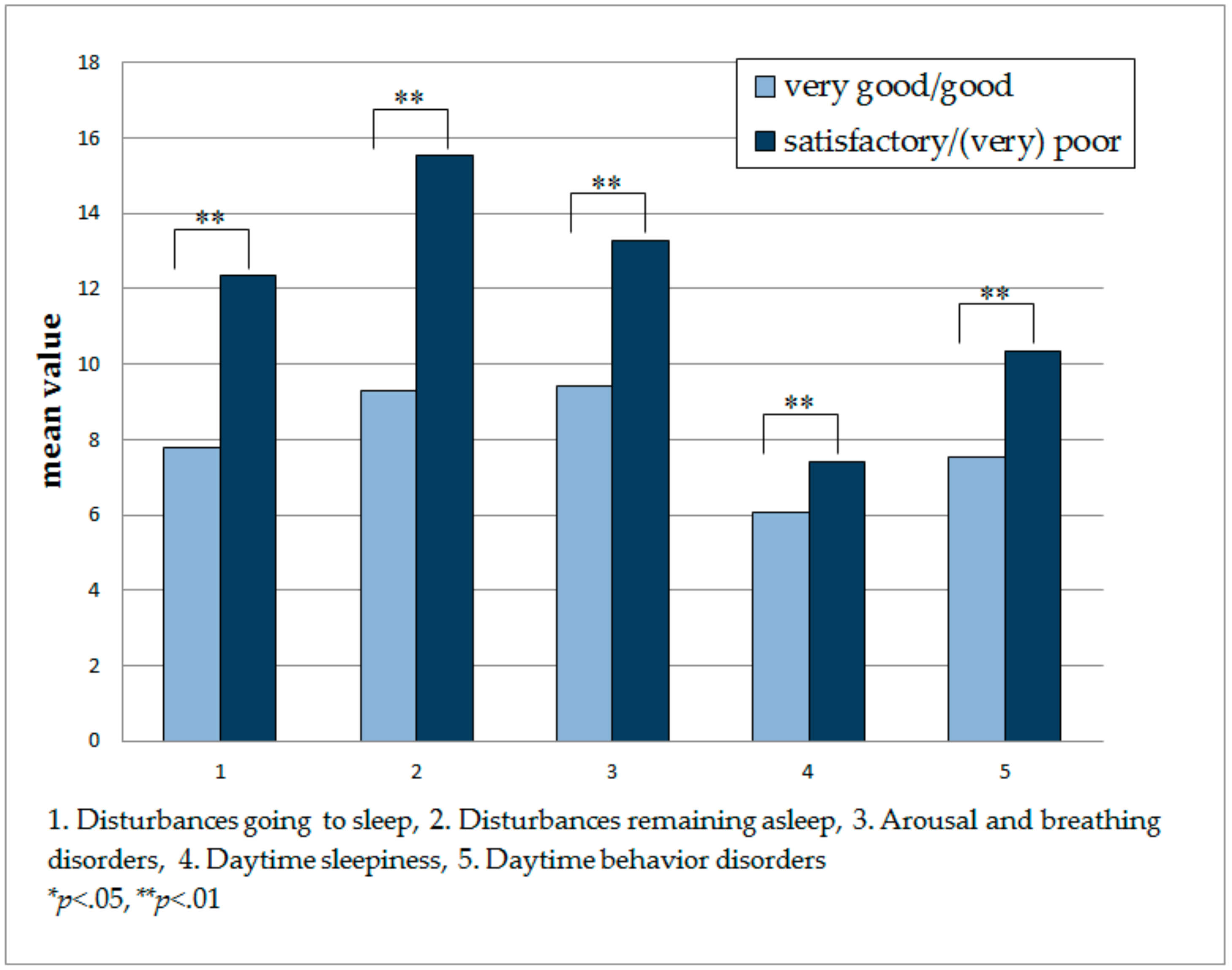

3.2. Relationship between the Global Rating of a Child’s Sleep and the SNAKE Scales

3.3. Relationship between Age and Sleep Ratings

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fraser, L.K.; Miller, M.; Hain, R.; Norman, P.; Aldridge, J.; McKinney, P.A.; Parslow, R.C. Rising national prevalence of life-limiting conditions in children in england. Pediatrics 2012, 129, e923–e929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fraser, L.K.; Lidstone, V.; Miller, M.; Aldridge, J.; Norman, P.; McKinney, P.A.; Parslow, R.C. Patterns of diagnoses among children and young adults with life-limiting conditions: A secondary analysis of a national dataset. Palliat. Med. 2014, 28, 513–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garske, D.; Schmidt, P.; Hasan, C.; Wager, J.; Zernikow, B. Palliativversorgung auf der pädiatrischen palliativstation “lichtblicke”—Eine retrospektive studie. Palliativmedizin 2016, 17, 302–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tietze, A.L.; Blankenburg, M.; Hechler, T.; Michel, E.; Koh, M.; Schluter, B.; Zernikow, B. Sleep disturbances in children with multiple disabilities. Sleep Med. Rev. 2012, 16, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Academy of Sleep Medicine. International Classification of Sleep Disorders: Diagnostic and Coding Manual, 2nd ed.; American Academy of Sleep Medicine: Westchester, IL, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Stores, G. Children’s sleep disorders: Modern approaches, developmental effects, and children at special risk. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 1999, 41, 568–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atmawidjaja, R.W.; Wong, S.W.; Yang, W.W.; Ong, L.C. Sleep disturbances in malaysian children with cerebral palsy. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2014, 56, 681–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Annaz, D.; Hill, C.M.; Ashworth, A.; Holley, S.; Karmiloff-Smith, A. Characterisation of sleep problems in children with Williams syndrome. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2011, 32, 164–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandeleur, M.; Walter, L.M.; Armstrong, D.S.; Robinson, P.; Nixon, G.M.; Horne, R.S. How well do children with cystic fibrosis sleep? An actigraphic and questionnaire-based study. J. Pediatr. 2017, 182, 170–176. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Newman, C.J.; O’Regan, M.; Hensey, O. Sleep disorders in children with cerebral palsy. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2006, 48, 564–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bloetzer, C.; Jeannet, P.Y.; Lynch, B.; Newman, C.J. Sleep disorders in boys with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Acta Paediatr. 2012, 101, 1265–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pera, M.C.; Romeo, D.M.; Graziano, A.; Palermo, C.; Messina, S.; Baranello, G.; Coratti, G.; Massaro, M.; Sivo, S.; Arnoldi, M.T.; et al. Sleep disorders in spinal muscular atrophy. Sleep Med. 2017, 30, 160–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ingram, D.G.; Churchill, S.S. Sleep problems in children with agenesis of the corpus callosum. Pediatr. Neurol. 2017, 67, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larson, A.M.; Ryther, R.C.; Jennesson, M.; Geffrey, A.L.; Bruno, P.L.; Anagnos, C.J.; Shoeb, A.H.; Thibert, R.L.; Thiele, E.A. Impact of pediatric epilepsy on sleep patterns and behaviors in children and parents. Epilepsia 2012, 53, 1162–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romeo, D.M.; Brogna, C.; Musto, E.; Baranello, G.; Pagliano, E.; Casalino, T.; Ricci, D.; Mallardi, M.; Sivo, S.; Cota, F.; et al. Sleep disturbances in preschool age children with cerebral palsy: A questionnaire study. Sleep Med. 2014, 15, 1089–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wirrell, E.; Blackman, M.; Barlow, K.; Mah, J.; Hamiwka, L. Sleep disturbances in children with epilepsy compared with their nearest-aged siblings. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2005, 47, 754–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramgopal, S.; Shah, A.; Zarowski, M.; Vendrame, M.; Gregas, M.; Alexopoulos, A.V.; Loddenkemper, T.; Kothare, S.V. Diurnal and sleep/wake patterns of epileptic spasms in different age groups. Epilepsia 2012, 53, 1170–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tietze, A.L.; Zernikow, B.; Michel, E.; Blankenburg, M. Sleep disturbances in children, adolescents, and young adults with severe psychomotor impairment: Impact on parental quality of life and sleep. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2014, 56, 1187–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morelius, E.; Hemmingsson, H. Parents of children with physical disabilities—Perceived health in parents related to the child’s sleep problems and need for attention at night. Child Care Health Dev. 2014, 40, 412–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adlington, K.; Liu, A.J.; Nanan, R. Sleep disturbances in the disabled child—A case report and literature review. Aust. Fam. Physician 2006, 35, 711–715. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Blankenburg, M.; Tietze, A.L.; Hechler, T.; Hirschfeld, G.; Michel, E.; Koh, M.; Zernikow, B. Snake: The development and validation of a questionnaire on sleep disturbances in children with severe psychomotor impairment. Sleep Med. 2013, 14, 339–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruni, O.; Ottaviano, S.; Guidetti, V.; Romoli, M.; Innocenzi, M.; Cortesi, F.; Giannotti, F. The sleep disturbance scale for children (SDSC). Construction and validation of an instrument to evaluate sleep disturbances in childhood and adolescence. J. Sleep Res. 1996, 5, 251–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, R.; Halevy, A.; Shuper, A. Children’s sleep disturbance scale in differentiating neurological disorders. Pediatr. Neurol. 2013, 49, 465–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owens, J.A.; Spirito, A.; McGuinn, M. The children’s sleep habits questionnaire (CSHQ): Psychometric properties of a survey instrument for school-aged children. Sleep 2000, 23, 1043–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Churchill, S.S.; Kieckhefer, G.M.; Bjornson, K.F.; Herting, J.R. Relationship between sleep disturbance and functional outcomes in daily life habits of children with down syndrome. Sleep 2015, 38, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breau, L.M.; Camfield, C.S. Pain disrupts sleep in children and youth with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2011, 32, 2829–2840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wayte, S.; McCaughey, E.; Holley, S.; Annaz, D.; Hill, C.M. Sleep problems in children with cerebral palsy and their relationship with maternal sleep and depression. Acta Paediatr. 2012, 101, 618–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortesi, F.; Giannotti, F.; Ottaviano, S. Sleep problems and daytime behavior in childhood idiopathic epilepsy. Epilepsia 1999, 40, 1557–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byars, A.W.; Byars, K.C.; Johnson, C.S.; DeGrauw, T.J.; Fastenau, P.S.; Perkins, S.; Austin, J.K.; Dunn, D.W. The relationship between sleep problems and neuropsychological functioning in children with first recognized seizures. Epilepsy Behav. 2008, 13, 607–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tietze, A.L.; Zernikow, B.; Otto, M.; Hirschfeld, G.; Michel, E.; Koh, M.; Blankenburg, M. The development and psychometric assessment of a questionnaire to assess sleep and daily troubles in parents of children and young adults with severe psychomotor impairment. Sleep Med. 2014, 15, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otto, M.T.; Tietze, A.-L.; Zernikow, B.; Wager, J. Sleep Questionnaire for Children with Severe Psychomotor Impairments—Manual; The German Paediatric Pain Centre and Paediatric Palliative Care Centre, Children’s and Adolescents’ Clinic Datteln: Datteln, Germany; University of Witten/Herdecke: Witten, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sleep Questionnaire for Children with Severe Psychomotor Impairments Version 1.0. German Paediatric Pain Centre and Paediatric Palliative Care Centre. Available online: http://www.deutsches-kinderschmerzzentrum.de/fileadmin/media/PDF-Dateien/englisch/Snake_engl_23_06_15.pdf (accessed on 31 January 2018).

- Raina, P.; O’Donnell, M.; Rosenbaum, P.; Brehaut, J.; Walter, S.D.; Russell, D.; Swinton, M.; Zhu, B.; Wood, E. The health and well-being of caregivers of children with cerebral palsy. Pediatrics 2005, 115, e626–e636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zernikow, B. Palliativversorgung von Kindern, Jugendlichen und Jungen Erwachsenen; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Zernikow, B.; Gertz, B.; Hasan, C. Pädiatrische Palliativversorgung—Herausfordernd Anders. Bundesgesundheitsblatt 2017, 60, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Measure | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Disturbances going to sleep | - | - | - | - | - |

| 2. Disturbances remaining asleep | 0.57 ** | - | - | - | - |

| 3. Arousal and breathing disorders | 0.34 ** | 0.45 ** | - | - | - |

| 4. Daytime sleepiness | 0.10 | 0.36 ** | 0.37 ** | - | - |

| 5. Daytime behavior disorders | 0.45 ** | 0.50 ** | 0.30 ** | 0.14 * | - |

| 6. Global sleep rating | 0.61 ** | 0.73 ** | 0.41 ** | 0.23 ** | 0.44 ** |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dreier, L.A.; Zernikow, B.; Blankenburg, M.; Wager, J. A Sleep Questionnaire for Children with Severe Psychomotor Impairment (SNAKE)—Concordance with a Global Rating of Sleep Quality. Children 2018, 5, 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/children5020020

Dreier LA, Zernikow B, Blankenburg M, Wager J. A Sleep Questionnaire for Children with Severe Psychomotor Impairment (SNAKE)—Concordance with a Global Rating of Sleep Quality. Children. 2018; 5(2):20. https://doi.org/10.3390/children5020020

Chicago/Turabian StyleDreier, Larissa Alice, Boris Zernikow, Markus Blankenburg, and Julia Wager. 2018. "A Sleep Questionnaire for Children with Severe Psychomotor Impairment (SNAKE)—Concordance with a Global Rating of Sleep Quality" Children 5, no. 2: 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/children5020020