Communicating Effectively in Pediatric Cancer Care: Translating Evidence into Practice

Abstract

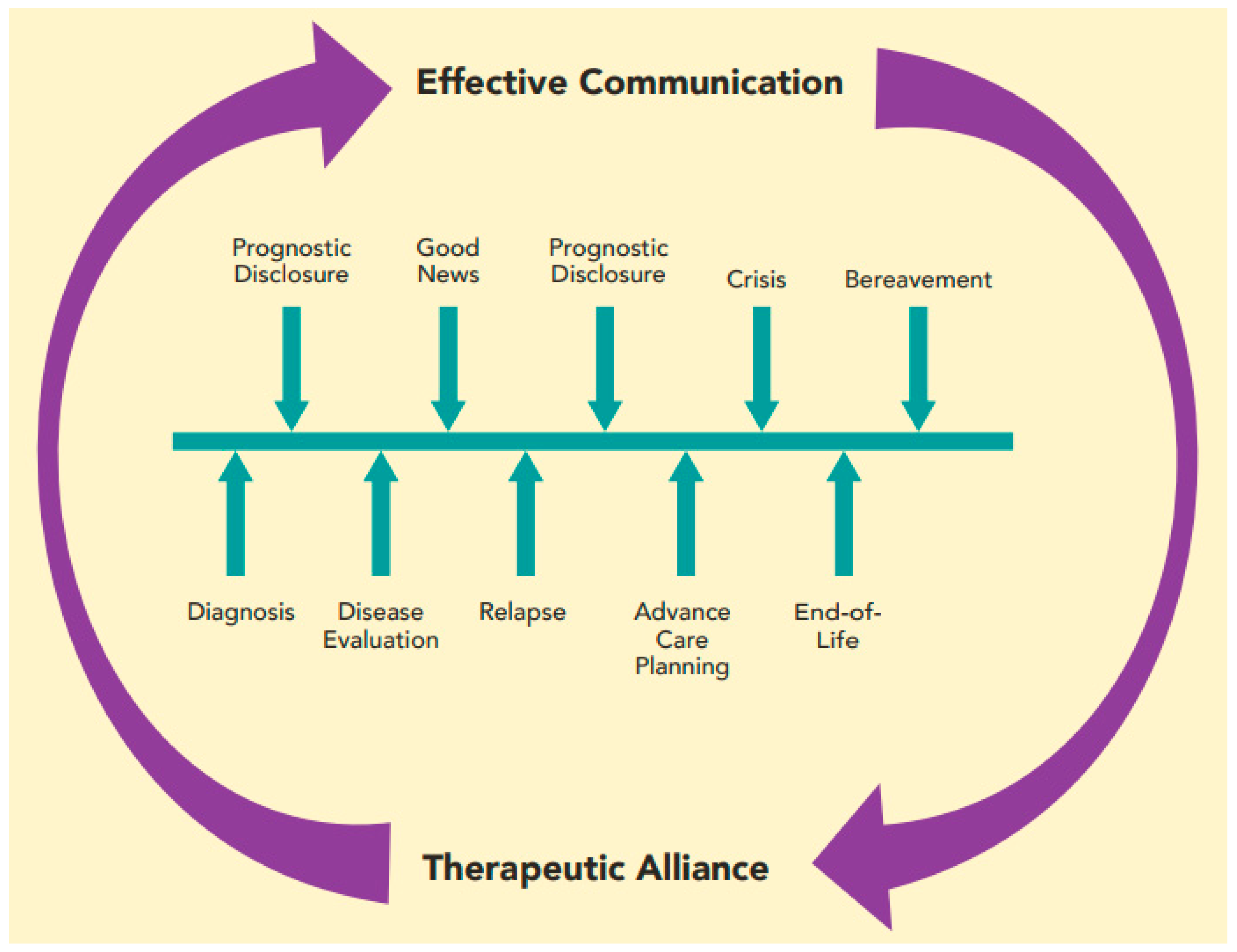

:1. Introduction

2. Communicating Diagnosis to Families in Distress

3. Prognostic Communication and the Importance of Hope

4. Communication with Families at the End of Life and During Bereavement

5. Cultivating Therapeutic Alliance in the Patient–Provider Relationship

6. Involving the Child

7. Communicating with Siblings and the Extended Family

8. An Interdisciplinary Team Approach to Communication

9. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ward, E.; DeSantis, C.; Robbins, A.; Kohler, B.; Jemal, A. Childhood and adolescent cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2014, 64, 83–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolfe, J.; Klar, N.; Grier, H.E.; Duncan, J.; Salem-Schatz, S.; Emanuel, E.J.; Weeks, J.C. Understanding of prognosis among parents of children who died of cancer. JAMA 2000, 284, 2469–2475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mack, J.W.; Grier, H.E. The Day One Talk. J. Clin. Oncol. 2004, 22, 563–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagerty, R.G.; Butow, P.N.; Ellis, P.M.; Dimitry, S.; Tattersall, M.H.N. Communicating prognosis in cancer care: A systematic review of the literature. Ann. Oncol. 2005, 16, 1005–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sisk, B.A.; Mack, J.W.; Ashworth, R.; DuBois, J. Communication in pediatric oncology: State of the field and research agenda. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2018, 65, e26727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epstein, R.M.; Street, R.L., Jr. Patient-Centered Communication in Cancer Care: Promoting Healing and Reducing Suffering; NIH Publication No. 07-6225; National Cancer Institute: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hays, R.M.; Valentine, J.; Haynes, G.; Geyer, J.R.; Villareale, N.; Mckinstry, B.; Varni, J.W.; Churchill, S.S. The seattle pediatric palliative care project: Effects on family satisfaction and health-related quality of life. J. Palliat. Med. 2006, 9, 716–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mack, J.W.; Weeks, J.C.; Wright, A.A.; Block, S.D.; Prigerson, H.G. End-of-life discussions, goal attainment, and distress at the end of life: Predictors and outcomes of receipt of care consistent with preferences. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010, 28, 1203–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nyborn, J.A.; Olcese, M.; Nickerson, T.; Mack, J.W. “Don’t try to cover the sky with your hands”: Parents’ experiences with prognosis communication about their children with advanced cancer. J. Palliat. Med. 2016, 19, 626–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ptacek, J.T.; Ptacek, J.J. Patients’ perceptions of receiving bad news about cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2001, 19, 4160–4164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mack, J.W.; Smith, T.J. Reasons why physicians do not have discussions about poor prognosis, why it matters, and what can be improved. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 30, 2715–2717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mack, J.W.; Wolfe, J.; Cook, E.F.; Grier, H.E.; Cleary, P.D.; Weeks, J.C. Hope and prognostic disclosure. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007, 25, 5636–5642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mack, J.W.; Cook, E.F.; Wolfe, J.; Grier, H.E.; Cleary, P.D.; Weeks, J.C. Understanding of prognosis among parents of children with cancer: Parental optimism and the parent-physician interaction. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007, 25, 1357–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mack, J.W.; Wolfe, J.; Grier, H.E.; Cleary, P.D.; Weeks, J.C. Communication about prognosis between parents and physicians of children with cancer: Parent preferences and the impact of prognostic information. J. Clin. Oncol. 2006, 24, 5265–5270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorne, S.; Oglov, V.; Armstrong, E.-A.; Hislop, T.G. Prognosticating futures and the human experience of hope. Palliat. Support. Care 2007, 5, 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamihara, J.; Nyborn, J.A.; Olcese, M.E.; Nickerson, T.; Mack, J.W. Parental Hope for Children with Advanced Cancer. Pediatrics 2015, 135, 868–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feudtner, C. Collaborative Communication in Pediatric Palliative Care: A Foundation for Problem-Solving and Decision-Making. Pediatr. Clin. N. Am. 2007, 54, 583–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mack, J.W.; Cronin, A.M.; Kang, T.I. Decisional regret among parents of children with cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 34, 4023–4029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Back, A.L.; Arnold, R.M.; Baile, W.F.; Tulsky, J.A.; Fryer-Edwards, K. Approaching difficult communication tasks in oncology. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2005, 55, 164–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, V.A.; Jacobsen, J.; Greer, J.A.; Pirl, W.F.; Temel, J.S.; Back, A.L. The cultivation of prognostic awareness through the provision of early palliative care in the ambulatory setting: A communication guide. J. Palliat. Med. 2013, 16, 894–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Quality Forum. National Voluntary Consensus Standards for Nursing-Sensitive Care: A Consensus Report; National Quality Forum: Washington, DC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Maurer, S.H.; Hinds, P.S.; Spunt, S.L.; Furman, W.L.; Kane, J.R.; Baker, J.N. Decision making by parents of children with incurable cancer who opt for enrollment on a phase I trial compared with choosing a do not resuscitate/terminal care option. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010, 28, 3292–3298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shinjo, T.; Morita, T.; Hirai, K.; Miyashita, M.; Sato, K.; Tsuneto, S.; Shima, Y. Care for imminently dying cancer patients: Family members’ experiences and recommendations. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010, 28, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michon, B.; Balkou, S.; Hivon, R.; Cyr, C. Death of a child: Parental perception of grief intensity—End-of-life and bereavement care. Paediatr. Child Health 2003, 8, 363–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgs, E.J.; McClaren, B.J.; Sahhar, M.A.R.; Ryan, M.M.; Forbes, R. “A short time but a lovely little short time”: Bereaved parents’ experiences of having a child with spinal muscular atrophy type 1. J. Paediatr. Child Health 2016, 52, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meert, K.L.; Thurston, C.S.; Thomas, R. Parental coping and bereavement outcome after the death of a child in the pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatr. Crit. Care Med. 2001, 2, 324–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Contro, N.; Larson, J.; Scofield, S.; Sourkes, B.; Cohen, H. Family perspectives on the quality of pediatric palliative care. JAMA 2002, 156, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snaman, J.M.; Kaye, E.C.; Torres, C.; Gibson, D.V.; Baker, J.N. Helping parents live with the hole in their heart: The role of health care providers and institutions in the bereaved parents’ grief journeys. Cancer 2016, 122, 2757–2765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jankovic, M.; Masera, G.; Uderzo, C.; Conter, V.; Adamoli, L.; Spinetta, J.J. Meetings with parents after the death of their child from leukemia. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 1989, 6, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mead, N.; Bower, P. Patient-centredness: A conceptual framework and review of the empirical literature. Soc. Sci. Med. 2000, 51, 1087–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trevino, K.M.; Fasciano, K.; Prigerson, H.G. Patient-oncologist alliance, psychosocial well-being, and treatment adherence among young adults with advanced cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 31, 1683–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mack, J.W.; Block, S.D.; Nilsson, M.; Wright, A.; Trice, E.; Friedlander, R.; Paulk, E.; Prigerson, H.G. Measuring therapeutic alliance between oncologists and patients with advanced cancer: The human connection scale. Cancer 2009, 115, 3302–3311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trevino, K.M.; Maciejewski, P.K.; Epstein, A.S.; Prigerson, H.G. The lasting impact of the therapeutic alliance: Patient-oncologist alliance as a predictor of caregiver bereavement adjustment. Cancer 2015, 121, 3534–3542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masera, G.; Spinetta, J.J.; Jankovic, M.; Ablin, A.R.; Buchwall, I.; Van Dongen-Melman, J.; Eden, T.; Epelman, C.; Green, D.M.; Kosmidis, H.V.; et al. Guidelines for a therapeutic alliance between families and staff: A report of the SIOP Working Committee on Psychosocial Issues in Pediatric Oncology. Med. Pediatr. Oncol. 1998, 30, 183–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavin, L.A.; O’Malley, J.E.; Koocher, G.P.; Foster, D.J. Communication of the cancer diagnosis to pediatric patients: Impact on long-term adjustment. Am. J. Psychiatry 1982, 139, 179–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palazzi, D.L.; Lorin, M.I.; Turner, T.L.; Ward, M.A.; Cabrera, A.G. Communicating with Pediatric Patients and Their Families: The Texas Children’s Hospital Guide for Physicians, Nurses and Other Healthcare Professionals; Texas Children’s Hospital: Houston, TX, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Levine, D.; Lam, C.G.; Cunningham, M.J.; Remke, S.; Chrastek, J.; Klick, J.; Macauley, R.; Baker, J.N. Best practices for pediatric palliative cancer care: A primer for clinical providers. J. Support. Oncol. 2013, 11, 114–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nitschke, R.; Caldwell, S.; Jay, S. Therapeutic choices in end-stage cancer. J. Pediatr. 1986, 108, 330–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyon, M.E.; McCabe, M.A.; Patel, K.M.; D’angelo, L.J. What do adolescents want? An exploratory study regarding end-of-life decision-making. J. Adolesc. Health 2004, 35, 529.e1–529.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weaver, M.S.; Baker, J.N.; Gattuso, J.S.; Gibson, D.V.; Sykes, A.D.; Hinds, P.S. Adolescents’ preferences for treatment decisional involvement during their cancer. Cancer 2015, 121, 4416–4424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyon, M.E.; Garvie, P.A.; McCarter, R.; Briggs, L.; He, J.; D’Angelo, L.J. Who will speak for me? Improving end-of-life decision-making for adolescents with HIV and their families. Pediatrics 2009, 123, e199–e206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dallas, R.H.; Kimmel, A.; Wilkins, M.L.; Rana, S.; Garcia, A.; Cheng, Y.I.; Wang, J.; Lyon, M.E. Acceptability of family-centered advanced care planning for adolescents with HIV. Pediatrics 2016, 138, e20161854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madrigal, V.N.; McCabe, B.; Cecchini, C.L.M.E. The respecting choices interview: Qualitative assessment. In Proceedings of the Pediatric Academic Societies Meeting, San Francisco, CA, USA, 6–9 May 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Aging with Dignity. Available online: https://www.agingwithdignity.org/shop/product-details/voicing-my-choices (accessed on 8 March 2018).

- Van der Geest, I.M.M.; van den Heuvel-Eibrink, M.M.; van Vliet, L.M.; Pluijm, S.M.F.; Streng, I.C.; Michiels, E.M.C.; Pieters, R.; Darlington, A.-S.E. Talking about death with children with incurable cancer: Perspectives from parents. J. Pediatr. 2015, 167, 1320–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kreicbergs, U.; Valdimarsdóttir, U.; Onelöv, E.; Henter, J.-I.; Steineck, G. Talking about death with children who have severe malignant disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 351, 1175–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaye, E.C.; Snaman, J.M.; Johnson, L.; Levine, D.; Powell, B.; Love, A.; Smith, J.; Ehrentraut, J.H.; Lyman, J.; Cunningham, M.; et al. Communication with children with cancer and their families throughout the illness journey and at the end-of-life. In Palliative Care in Pediatric Oncology; Wolfe, J., Jones, B.L., Kreicbergs, U., Jankovic, M., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Levetown, M. Communicating with children and families: From everyday interactions to skill in conveying distressing information. Pediatrics 2008, 121, e1441–e1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaab, E.M.; Owens, G.R.; MacLeod, R.D. Siblings caring for and about pediatric palliative care patients. J. Palliat. Med. 2014, 17, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eilertsen, M.-E.B.; Eilegård, A.; Steineck, G.; Nyberg, T.; Kreicbergs, U. Impact of social support on bereaved siblings’ anxiety. J. Pediatr. Oncol. Nurs. 2013, 30, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahlin, C. (Ed.) Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care, 3rd ed.; National Concensus Project for quality palliative care; Hospice and Palliative nurses Association: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, A.R.; Bastian, R.G.; Apenteng, B.A. Communication within hospice interdisciplinary teams: A narrative review. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Med. 2016, 33, 996–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linz, A. Interdisciplinary Care Team Development for Pediatric Oncology Palliative Treatment; The University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center: Oklahoma City, OK, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Fineberg, I.C. Preparing professionals for family conferences in palliative care: Evaluation results of an interdisciplinary approach. J. Palliat. Med. 2005, 8, 857–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powazki, R.D.; Walsh, D. The Family conference in palliative medicine: A practical approach. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Med. 2014, 31, 678–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powazki, R.D. The family conference in oncology: Benefits for the patient, family, and physician. Semin. Oncol. 2011, 38, 407–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roth, M.; Wang, D.; Kim, M.; Moody, K. An assessment of the current state of palliative care education in pediatric hematology/oncology fellowship training. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2009, 53, 647–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kushner, K.; Meyer, D. Family physicians’ perceptions of the family conference. J. Fam. Pract. 1989, 28, 65–68. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

| Functions | Communication Methods |

|---|---|

| Responding to emotions | Evaluate and appraise distress Offer validation, empathy, and support |

| Exchanging information | Identify depth of information the patient or caregiver desires |

| Acknowledge the abundance of information available online | |

| Consider findings presented without seeming dismissive | |

| Making decisions | Partner with patient and family to identify goals of care |

| Align treatment plan with stated goals | |

| Fostering healing relationships | Develop mutual trust, understanding, and commitment |

| Clarify roles and expectations of patient and provider | |

| Enabling self-management | Encourage active engagement in all aspects of care |

| Invite discussion and questions from patients and families | |

| Managing uncertainty | Recognize limitations in knowledge |

| Name uncertainties and address associated fears |

| Components | Key Steps | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Prepare the setting | Quiet location | |

| All desired parties present and seated | ||

| Minimize interruptions | ||

| Elicit understanding | One HCP takes the lead, asks family to describe their current understanding | “What have you heard so far about what is going on?” |

| Provide “warning shot” | “I’m afraid we have difficult news to discuss.” | |

| “Unfortunately, the scans didn’t show what we hoped.” | ||

| Give the diagnosis | Use clear language | “Your child has leukemia, which is a kind of cancer.” |

| Avoid euphemisms | ||

| Use the word cancer | ||

| Pause | Stop speaking | |

| Allow the family to process information | ||

| Elicit questions | ||

| Discuss treatment | Discuss expected location and duration of treatment | “We will use a combination of surgery followed by medicines called chemotherapy to treat the cancer. Most of the chemotherapy will be given during inpatient hospitalizations lasting 3–5 days. Overall, treatment will last for about 6 months.” |

| Explain different modalities | ||

| Provide alternative options | ||

| Pause | Stop speaking | |

| Allow the family to process information | ||

| Elicit questions | ||

| Define goals of therapy | Provide clear, honest communication regarding curative intent | “The goal of therapy is to cure your child’s cancer.” |

| “Unfortunately, there is no cure for this cancer at this time. The goal of treatment will be to minimize symptoms, improve quality of life, and prolong life.” | ||

| Pause | Stop speaking | |

| Allow the family to process information | ||

| Elicit questions | ||

| Address causation | If accurate, clearly state that cancer was not preventable | “We don’t know what causes this kind of cancer, but we know that there is nothing that you or your child did to cause it. You did the right thing by bringing your child in when you did.” |

| Dispel concerns that cancer resulted from something child or family did or did not do | ||

| Summarize key points | Restate the diagnosis, goals of therapy, and discussion of causation | “For today, what I want you to understand is that your child has cancer. We plan to treat with chemotherapy and the goal of treatment is cure. There is nothing you or your child could have done to prevent this and this is not your fault.” |

| Conclude conversation | Offer reassurance that information will be discussed again at future visits | “We will discuss all of this information again, so don’t worry if you can’t remember everything. I will see you in clinic again tomorrow afternoon. If you have any concerns before then, you can always call the clinic at...” |

| Plan for next visit | ||

| Provide contact information for urgent issues |

| Step 1. Assess understanding of disease and prognosis | |

| |

| Step 2. Facilitate development of prognostic awareness by imagining poorer health | |

| |

| Step 3. Assess response and consider urgency of need to deliver prognostic information | |

| If the patient is ambivalent about prognostic discussion and disease is stable: |

|

| If the patient is ambivalent about prognosis discussion but disease is worsening: |

|

| If the patient is ready to discuss prognosis, regardless of disease state: |

|

|

| Age | Communication Goals |

|---|---|

| Infants |

|

| Toddlers |

|

| School-Aged Children |

|

| Adolescents |

|

| Potential Pitfalls | Phrases to Avoid | Alternative Phrases |

|---|---|---|

| Placing burden of understanding on the family | “Do you understand what I’ve told you?” | “Does this make sense?”“Tell me what you’ve been hearing from the team.” |

| Appearing to give up | “There is nothing more we can do.” | “I wish we had a treatment to cure this disease. We will continue to do everything in our power to care for (child’s name).” |

| Claiming understanding | “I understand how you feel.” | “I can’t imagine how you must be feeling. I wish we had better news. What might be helpful for you right now?” |

| Using clichés, emphasizing the positives | “This will make you a better/stronger person.” | “May I just sit with you for a while?” |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Blazin, L.J.; Cecchini, C.; Habashy, C.; Kaye, E.C.; Baker, J.N. Communicating Effectively in Pediatric Cancer Care: Translating Evidence into Practice. Children 2018, 5, 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/children5030040

Blazin LJ, Cecchini C, Habashy C, Kaye EC, Baker JN. Communicating Effectively in Pediatric Cancer Care: Translating Evidence into Practice. Children. 2018; 5(3):40. https://doi.org/10.3390/children5030040

Chicago/Turabian StyleBlazin, Lindsay J., Cherilyn Cecchini, Catherine Habashy, Erica C. Kaye, and Justin N. Baker. 2018. "Communicating Effectively in Pediatric Cancer Care: Translating Evidence into Practice" Children 5, no. 3: 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/children5030040