I62− Anion Composed of Two Asymmetric Triiodide Moieties: A Competition between Halogen and Hydrogen Bond

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

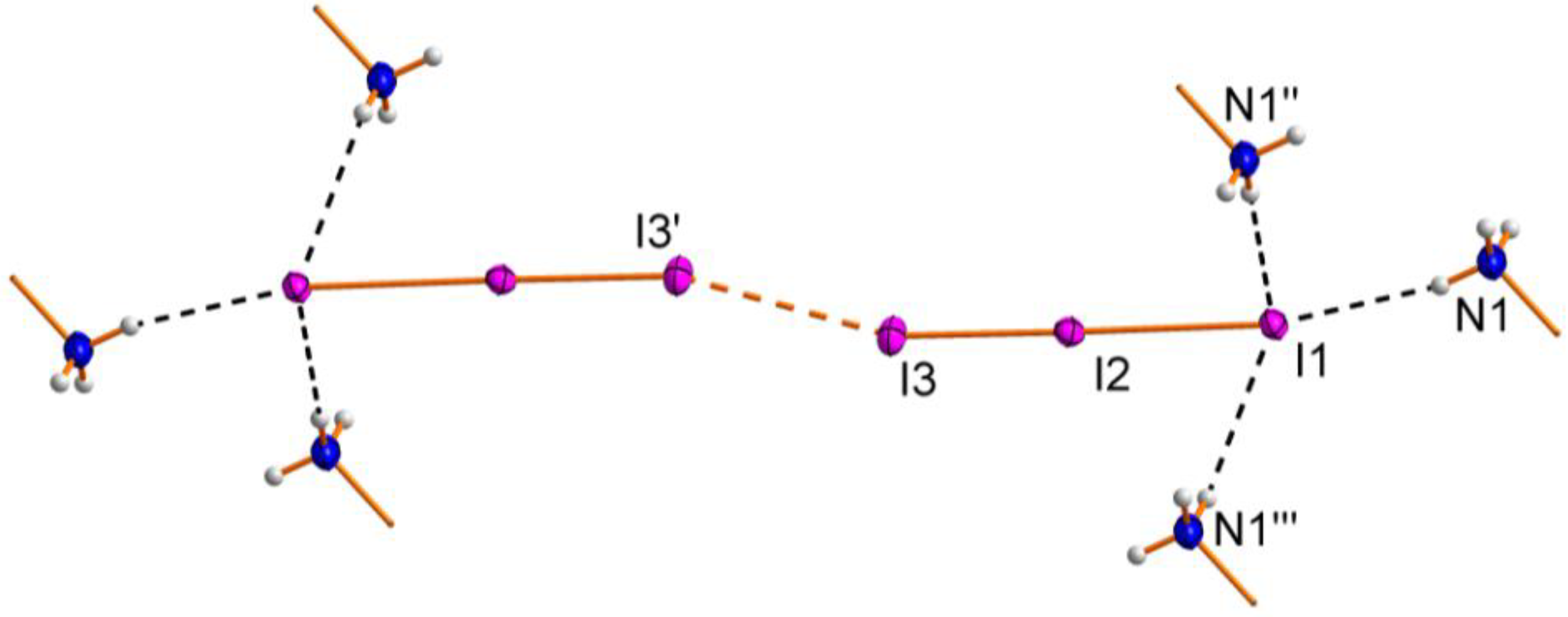

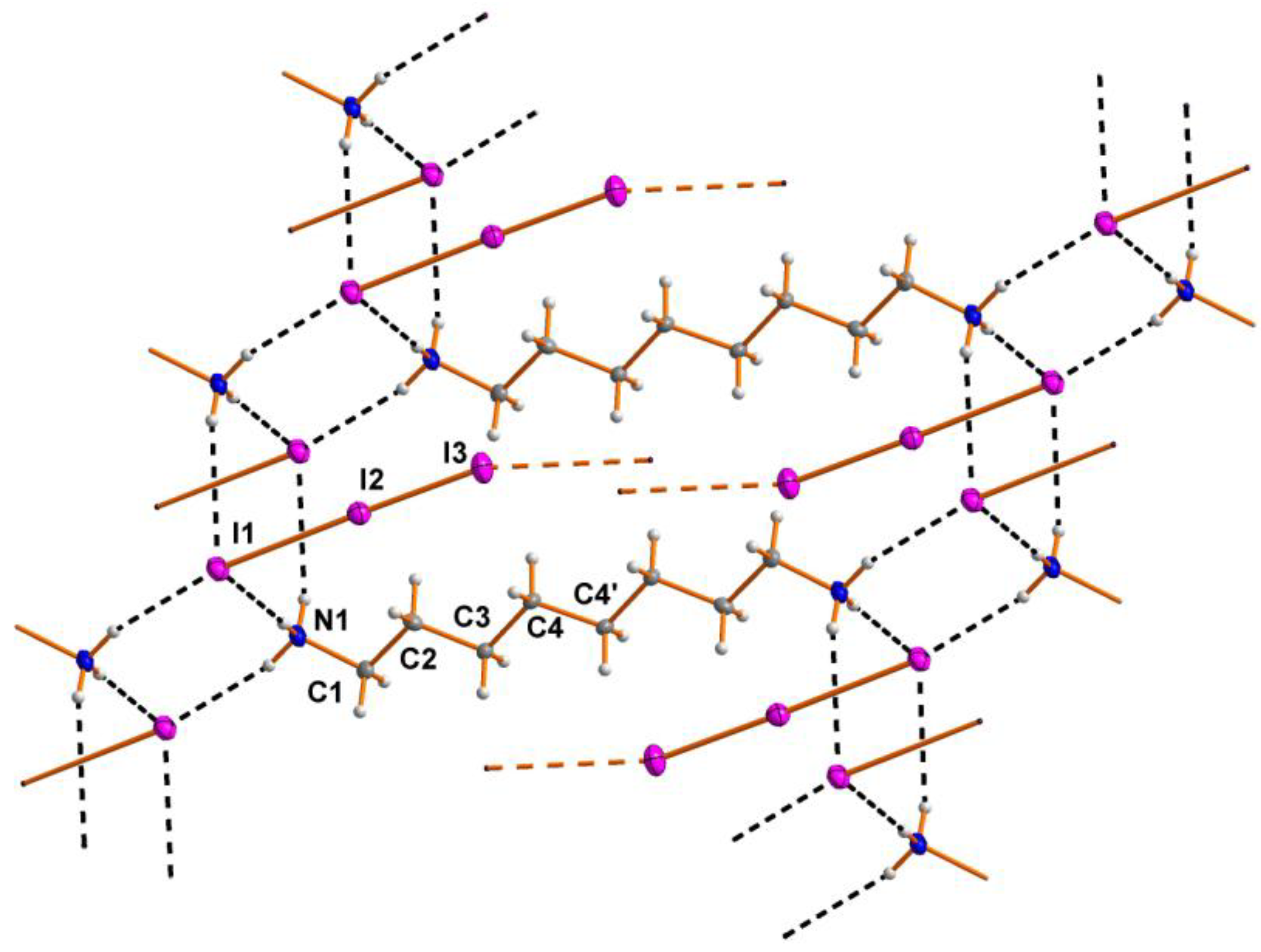

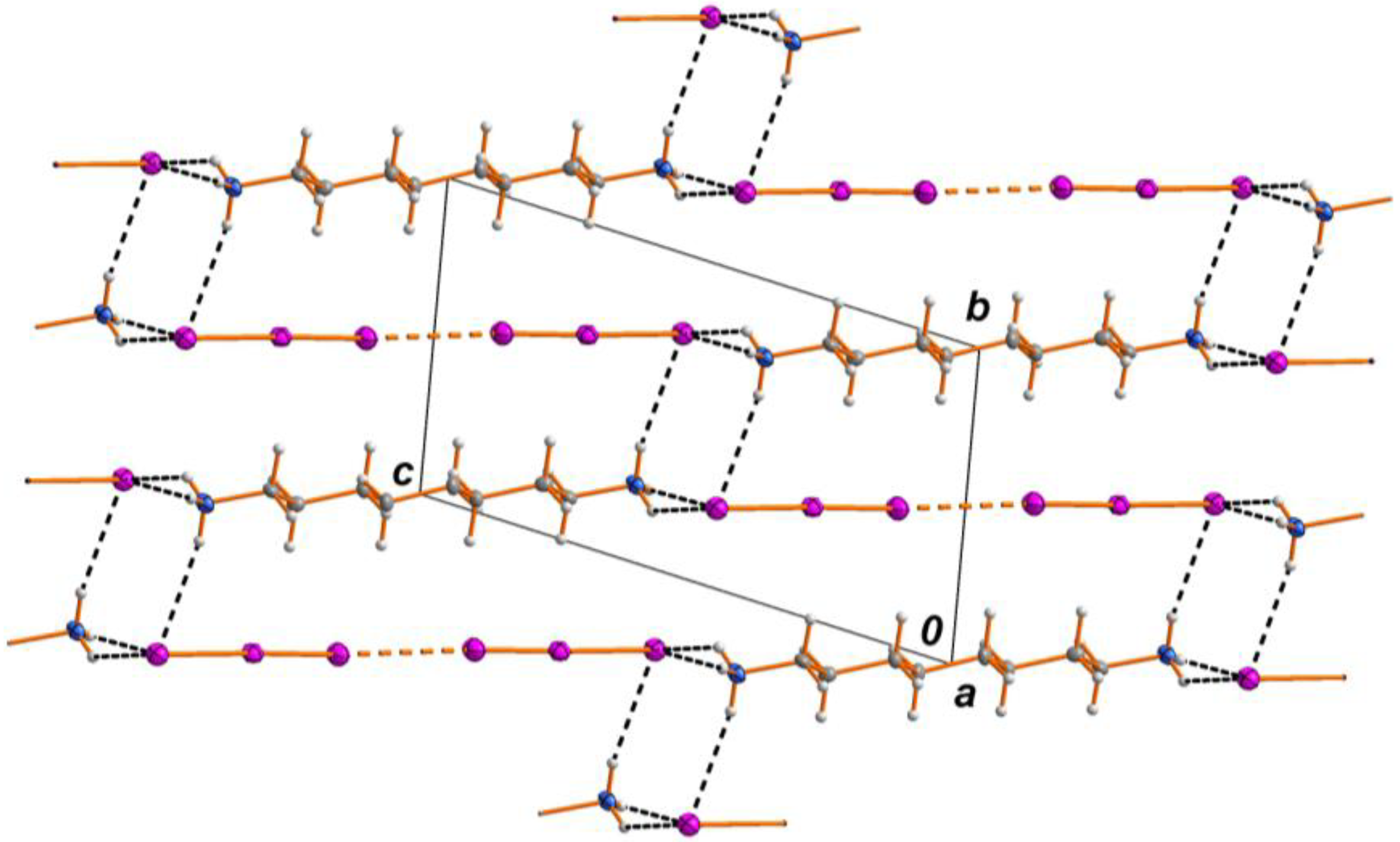

2.1. Crystal Structure

| Atoms | Distance | Atoms | Distance |

|---|---|---|---|

| I1–I2 | 3.1778(4) | I2–I3 | 2.7739(4) |

| I3–I3' | 3.5017(2) | N1–C1 | 1.500(6) |

| C1–C2 | 1.516(6) | C2–C3 | 1.537(7) |

| C3–C4 | 1.526(6) | C4–C4'' | 1.528(9) |

| I1–I2–I3 | 178.34(2) | I2–I3–I3' | 163.36(2) |

| N1–C1–C2–C3 | −176.8(4) | C1–C2–C3–C4 | 179.0(4) |

| C2–C3–C4–C4'' | −177.5(5) | - | - |

| D―H∙∙∙A | D―H | H∙∙∙A | D∙∙∙A | < (DHA) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N1―H12∙∙∙I1 | 0.885(8) | 2.727(13) | 3.592(4) | 166(4) |

| N1―H11∙∙∙I1' | 0.893(8) | 2.810(12) | 3.688(4) | 168(4) |

| N1―H13∙∙∙I1'' | 0.891(8) | 2.93(3) | 3.653(5) | 139(4) |

2.2. Spectrosopy

3. Experimental

| Empirical formula | C8H22I6N2 |

|---|---|

| Formula weight | 907.68 |

| T/K | 100(1) |

| Crystal system / Space group | triclinic/P-1 |

| a (Å) | 6.20008(14) |

| b (Å) | 7.0452(2) |

| c (Å) | 12.5770(3) |

| α (°) | 76.531(2) |

| β (°) | 78.842(2) |

| γ (°) | 84.574(2) |

| V (Å3)/Z | 523.46(2)/1 |

| μ (mm−1) | 8.888 |

| Absorption correction | analytical |

| Tmin./Tmax. | 0.102/0.850 |

| Reflections*/reflections (I > 2σ(I)) | 5489/5185 |

| θ range (°) | 2.98–28.99 |

| R(F)[I > 2σ(I)]/wR(F2) [all data] | 0.0341/0.0888 |

| Parameters / restraints / completeness | 87/9/100% |

| Δρmax./Δρmin (e·Å−3 ) | 1.530/−1.058 |

| CCDC-number | 864870 |

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tebbe, K.-F. Polyhalogen Cations and Polyhalide Anions. In Homoatomic Rings, Chains and Macromolecules of Main-Group Elements, 1st ed.; Rheingold, A.L., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1977; pp. 551–606. [Google Scholar]

- Coppens, P. Structural Aspects of Iodine-Containing Low-Dimensional Materials. In Extended Linear Chain Compounds; Miller, J.S., Ed.; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1982; Volume 1, pp. 333–356. [Google Scholar]

- Blake, A.J.; Devillanova, F.A.; Gould, R.O.; Li, W.S.; Lippolis, V.; Parsons, S.; Radek, C.; Schröder, M. Template self-assembly of polyiodide networks. Chem. Soc. Rev. 1998, 27, 195–205. [Google Scholar]

- Svensson, P.H.; Kloo, L. Synthesis, structure, and bonding in polyiodide and metal iodide-iodine systems. Chem. Rev. 2003, 103, 1649–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloo, L.; Rosdahl, J.; Svensson, P.H. On the intra- and intermolecular bonding in polyiodides. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2002, 1203–1209. [Google Scholar]

- Metrangolo, P.; Meyer, F.; Pilati, T.; Resnati, G.; Terraneo, G. Halogen bonding in supramolecular chemistry. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 6114–6127. [Google Scholar]

- Resnati, G.; Metrangolo, P. Halogen Bonding. In Encyclopedia of Supramolecular Chemistry; Atwood, J.L., Steed, J.W., Eds.; Taylor & Francis: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2007; Volume 1, pp. 628–635. [Google Scholar]

- Hasell, T.; Schmidtmann, M.; Cooper, A.I. Molecular doping of porous organic cages. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 14920–14923. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, Z.; Wang, Q.-X.; Zeng, M.-H. Iodine release and recovery, influence of polyiodide anions on electrical conductivity and nonlinear optical activity in an interdigitated and interpenetrated bipillared-bilayer metal–organic framework. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 4857–4863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, A.S.P.; Visscher, L.; Bolvin, H.; Saue, T.; Knecht, S.; Fleig, T.; Eliav, E. The electronic structure of the triiodide ion from relativistic correlated calculations: A comparison of different methodologies. J. Chem. Phys. 2010, 133, 064305. [Google Scholar]

- Groenewald, F.; Esterhuysen, C.; Dillen, J. Extensive theoretical investigation: Influence of the electrostatic environment on the I3-···I3-–anion–anion interaction. Theor. Chem. Acc. 2012, 131, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Otsuka, M.; Mori, H.; Kikuchi, H.; Takano, K. Density functional theory calculations of iodine cluster anions: Structures, chemical bonding nature, and vibrational spectra. Comput. Theor. Chem. 2011, 973, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, T.; Hennemann, M.; Murray, J.; Politzer, P. Halogen bonding: The σ-hole. J. Mol. Model. 2007, 13, 291–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Politzer, P.; Murray, J.S.; Clark, T. Halogen bonding: An electrostatically-driven highly directional noncovalent interaction. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2010, 12, 7748–7757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Politzer, P.; Murray, J.S. Halogen bonding: An interim discussion. ChemPhysChem 2013, 14, 278–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O´Regan, B.; Grätzel, M. A low-cost, high-efficiency solar cell based on dye-sensitized colloidal TiO2 films. Nature 1991, 353, 737–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorlov, S.; Kloo, L. Ionic liquid electrolytes for dye-sensitized solar cells. Dalton Trans. 2008, 2655–2666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, S.; Jo, Y.; Kim, K.-J.; Jun, Y.; Han, C.-H. High performance dye-sensitized solar cells with alkylpyridinium iodide salts in electrolytes. Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2011, 3, 512–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowley, J.G.; Meyer, G.J. Di- and tri-iodide reactivity at illuminated titanium dioxide interfaces. J. Phys. Chem. C 2011, 115, 6156–6161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Sun, R.; Shi, C.; Wu, Y.; Xia, M. Application of diaminium iodides in binary ionic liquid electrolytes for dye-sensitized solar cells. Int. J. Photoenergy 2011, 986869:1–986869:5. [Google Scholar]

- Thorsmølle, V.K.; Topgaard, D.; Brauer, J.C.; Zakeeruddin, S.M.; Lindman, B.; Grätzel, M.; Moser, J.-E. Conduction through viscoelastic phase in a redox-active ionic liquid at reduced temperatures. Adv. Mater. 2012, 24, 781–784. [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein, L.; Yourey, W.; Gural, J.; Amatucci, G.G. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy of electrochemically self-assembled lithium-iodine batteries. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2008, 155, A590–A598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yourey, W.; Weinstein, L.; Amatucci, G.G. Structure and charge transport of polyiodide networks for electrolytically in-situ formed batteries. Solid State Ionics 2011, 204, 80–86. [Google Scholar]

- Tyagi, D.; Varma, S.; Bhattacharya, K.; Jain, D.; Tripathi, A.K.; Pillai, C.G.S.; Bharadwaj, S.R. Iodine speciation studies on Bunsen reaction of S–I cycle using spectroscopic techniques. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2012, 37, 3621–3625. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez, S.; Novoa, J.; Mota, F. The mechanism of electrical conductivity along polyhalide chains. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1986, 132, 531–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marks, T.J.; Kalina, D.W. Highly Conductive Halogenated Low-Dimensional Materials. In Extended Linear Chain Compounds; Miller, J.S., Ed.; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1982; Volume 1, pp. 197–331. [Google Scholar]

- Hosseini, M.W. Molecular tectonics: From molecular recognition of anions to molecular networks. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2003, 240, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aakeröy, C.B.; Champness, N.R.; Janiak, C. Recent advances in crystal engineering. CrystEngComm 2010, 12, 22–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunet, P.; Simard, M.; Wuest, J.D. Molecular tectonics. Porous hydrogen-bonded networks with unprecedented structural integrity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997, 119, 2737–2738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resnati, G.; Metrangolo, P. Tectons: Definition and Scope. In Encyclopedia of Supramolecular Chemistry; Atwood, J.L., Steed, J.W., Eds.; Taylor & Francis: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2007; Volume 1, pp. 1484–1492. [Google Scholar]

- Svensson, P.H.; Gorlov, M.; Kloo, L. Dimensional caging of polyiodides. Inorg. Chem. 2008, 47, 11464–11466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abate, A.; Brischetto, M.; Cavallo, G.; Lahtinen, M.; Metrangolo, P.; Pilati, T.; Radice, S.; Resnati, G.; Rissanen, K.; Terraneo, G. Dimensional encapsulation of I-∙∙∙I2∙∙∙I- in an organic salt crystal matrix. Chem. Commun. 2010, 46, 2724–2726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, M.K.; Graf, J.; Reiss, G.J. Dimer oder nicht dimer, das ist hier die Frage: Zwei benachbarte I3--Ionen eingeschlossen in Hohlräumen einer komplexen Wirtsstruktur. Z. Naturforsch. B 2010, 65, 1462–1466. (In German) [Google Scholar]

- García, M.D.; Martí-Rujas, J.; Metrangolo, P.; Peinador, C.; Pilati, T.; Resnati, G.; Terraneo, G.; Ursini, M. Dimensional caging of polyiodides: Cation-templated synthesis using bipyridinium salts. CrystEngComm 2011, 13, 4411–4416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Reiss, G.J.; van Megen, M. Two new polyiodides in the 4,4’-bipyridinium diiodide/iodine system. Z. Naturforsch. B 2012, 67, 5–10. [Google Scholar]

- Van Megen, M.; Reiss, G.J. The pseudosymmetric structure of bis(pentane-1,5-diaminium) iodide tris(triiodide). Acta Cryst. E 2012, 68, o1331–o1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, M.; Albrecht, M.; Gossen, V.; Peters, T.; Hoffmann, A.; Raabe, G.; Valkonen, A.; Rissanen, K. Anion–π interactions in salts with polyhalide anions: Trapping of I42−. Chem. Eur. J. 2010, 16, 12446–12453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garzón-Tovar, L.; Duarte-Ruiz, Á.; Wurst, K. Non-classical hydrogen bond (CH∙∙∙I) directed self-assembly formation of a novel 1D supramolecular polymer, based on a copper complex [Cu{(CH3)2SO}6]I4. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2013, 32, 64–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redel, E.; Röhr, C.; Janiak, C. An inorganic starch–iodine model. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 2009, 2103–2105. [Google Scholar]

- Takeoka, Y.; Fukasawa, M.; Matsui, T.; Kikuchi, K.; Rikukawa, M.; Sanui, K. Intercalated formation of two-dimensional and multi-layered perovskites in organic thin films. Chem. Commun. 2005, 378–380. [Google Scholar]

- Frank, W.; Reiss, G.J. Bis(1,6-diammoniohexane) tetraaquahydrogen(1+) hexachlororhodate(III) dichloride, [H3N(CH2)6NH3]2[H9O4][RhCl6]Cl2: Chain-like [H9O4]+ ions enclosed in the cavities of a complex organic-inorganic framework. Inorg. Chem. 1997, 36, 4593–4595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Yu, J.; Corma, A. Extra-large-pore zeolites: Bridging the gap between micro and mesoporous structures. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 3120–3145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vizi, M.Z.; Knobler, C.B.; Owen, J.J.; Khan, M.I.; Schubert, D.M. Structures of self-assembled nonmetal borates derived from α,ω-diaminoalkanes. Cryst. Growth Des. 2006, 6, 538–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidlhofer, B.; Pienack, N.; Bensch, W. Synthesis of inorganic-organic hybrid thiometallate materials with a special focus on thioantimonates and thiostannates and in situ X-Ray Scattering Studies of their Formation. Z. Naturforsch. B 2010, 65, 937–975. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, J.Y.; Schauss, V. A novel nanostructured open-channel coordination polymer with an included fused-polyiodide ring. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2002, 1945–1947. [Google Scholar]

- Reiss, G.J.; van Megen, M. Synthesis, structure and spectroscopy of a new polyiodide in the α,ω-diazaniumalkane iodide/iodine system. Z. Naturforsch. B 2012, 67, 447–451. [Google Scholar]

- Reiss, G.J. Personal communication to the Cambridge Structural Database. deposition number CCDC 786078. Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Reiss, G.J.; Engel, J.S. Crystal Engineering of a new layered polyiodide using 1,9-diammoniononane as a flexible template cation. Z. Naturforsch. B 2004, 59, 1114–1117. [Google Scholar]

- Reiss, G.J.; Engel, J.S. Hydrogen bonded 1,10-diammoniodecane—An example of an organo-template for the crystal engineering of polymeric polyiodides. CrystEngComm 2002, 4, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, M.; Marzilli, L.G.; Kistenmacher, T.J. Protonated 1-methylcytosine triiodide. Acta Cryst. B 1978, 34, 2030–2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tebbe, K.-F.; Freckmann, B.; Horner, M.; Hiller, W.; Strähle, J. Verfeinerung der Kristallstruktur des Ammoniumtriiodids, NH4I3. Acta Cryst. C 1985, 41, 660–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etter, M.C.; MacDonald, J.C.; Bernstein, J. Graph-set analysis of hydrogen-bond patterns in organic crystals. Acta Cryst. B 1990, 46, 256–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deplano, P.; Ferraro, J.R.; Mercuri, M.L.; Trogu, E.F. Structural and Raman spectroscopic studies as complementary tools in elucidating the nature of the bonding in polyiodides and in donor-I2 adducts. Coord. Chem. Rev. 1999, 188, 71–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrosetti, R.; Bellucci, G.; Bianchini, R.; Bigoli, F.; Deplano, P.; Pellinghelli, M.A.; Trogu, E.F. Kinetic and mechanistic study of the reaction between dithiomalonamides and diiodine. Crystal structure of the compounds 3,5-bis(ethylamino)-1,2-dithiolylium triiodide and 3,5-bis(morpholino)-1,2-dithiolylium iodide monohydrate. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1991, 2, 339–347. [Google Scholar]

- Kalina, D.W.; Lyding, J.W.; Ratajack, M.T.; Kannewurf, C.R.; Marks, T.J. Bromine as a partial oxidant. Oxidation state and charge transport in brominated nickel and palladium bis(diphenylglyoximates). A comparison with the iodinated materials and resonance Raman structure-spectra correlations for polybromides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1980, 102, 7854–7862. [Google Scholar]

- Egli, R.A. Neue Bestimmungsmethode für organisch gebundenes Iod, Brom und Chlor. Z. Anal. Chem. 1969, 247, 39–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CrysAlisPro, version 1.171.33.42; Oxford Diffraction Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 2009.

- Sheldrick, G.M. A short history of SHELX. Acta Cryst. A 2008, 64, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, B.C.; Coyle, J.A.; Ibers, J. Redetermination of the structure of nitrosylpenta-amminecobalt(III) dichloride. J. Chem. Soc. A 1971, 2146–2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peuronen, A.; Valkonen, A.; Kortelainen, M.; Rissanen, K.; Lahtinen, M. Halogen bonding-based “catch and release”: Reversible solid-state entrapment of elemental iodine with monoalkylated dabco salts. Cryst. Growth Des. 2012, 12, 4157–4169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, M.-H.; Wang, Q.-X.; Tan, Y.-X.; Hu, S.; Zhao, H.-X.; Long, L.-S.; Kurmoo, M. Rigid pillars and double walls in a porous metal-organic framework: Single-crystal to single-crystal, controlled uptake and release of iodine and electrical conductivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 2561–2563. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J.; Wang, D.; Guo, W.; Du, S.; Tang, Z.K. Reversible control of the orientation of iodine molecules inside the AlPO4–11 crystals. J. Phys. Chem. C 2012, 116, 4423–4430. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.; Chen, B.; Fredrickson, D.C.; DiSalvo, F.J.; Lobkovsky, E.; Adams, J.A. Crystal structures of (pyrene)10(i3−)4(i2)10 and [1,3,6,8-tetrakis(methylthio)pyrene]3(I3−)3(I2)7: structural trends in fused aromatic polyiodides. Chem. Mater. 2003, 15, 1420–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2013 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Van Megen, M.; Reiss, G.J. I62− Anion Composed of Two Asymmetric Triiodide Moieties: A Competition between Halogen and Hydrogen Bond. Inorganics 2013, 1, 3-13. https://doi.org/10.3390/inorganics1010003

Van Megen M, Reiss GJ. I62− Anion Composed of Two Asymmetric Triiodide Moieties: A Competition between Halogen and Hydrogen Bond. Inorganics. 2013; 1(1):3-13. https://doi.org/10.3390/inorganics1010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleVan Megen, Martin, and Guido J. Reiss. 2013. "I62− Anion Composed of Two Asymmetric Triiodide Moieties: A Competition between Halogen and Hydrogen Bond" Inorganics 1, no. 1: 3-13. https://doi.org/10.3390/inorganics1010003