Manganese(I)-Based CORMs with 5-Substituted 3-(2-Pyridyl)Pyrazole Ligands

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results

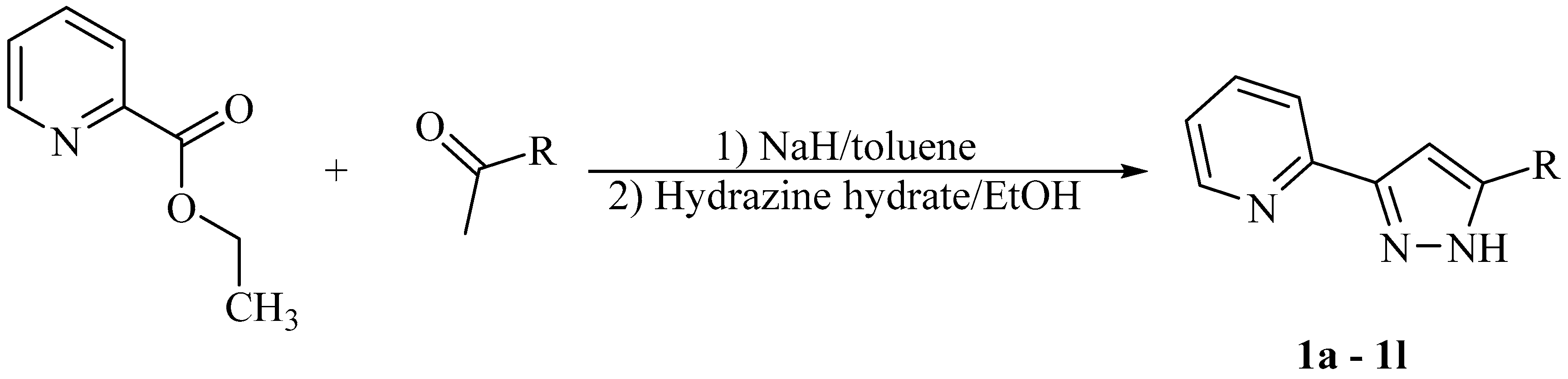

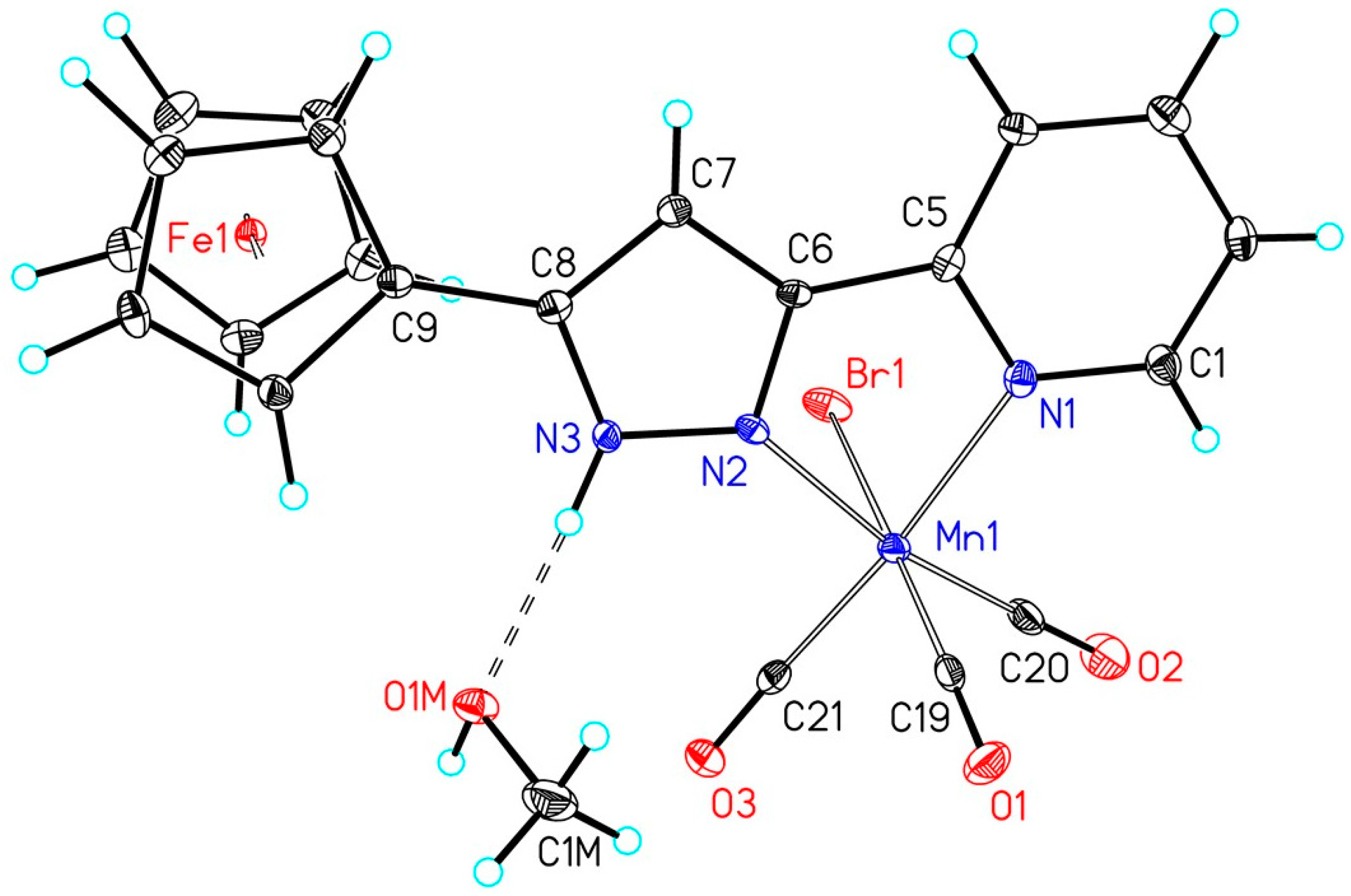

2.1. Synthesis of [(OC)3Mn(Br)(2-PyPzRH)] (2)

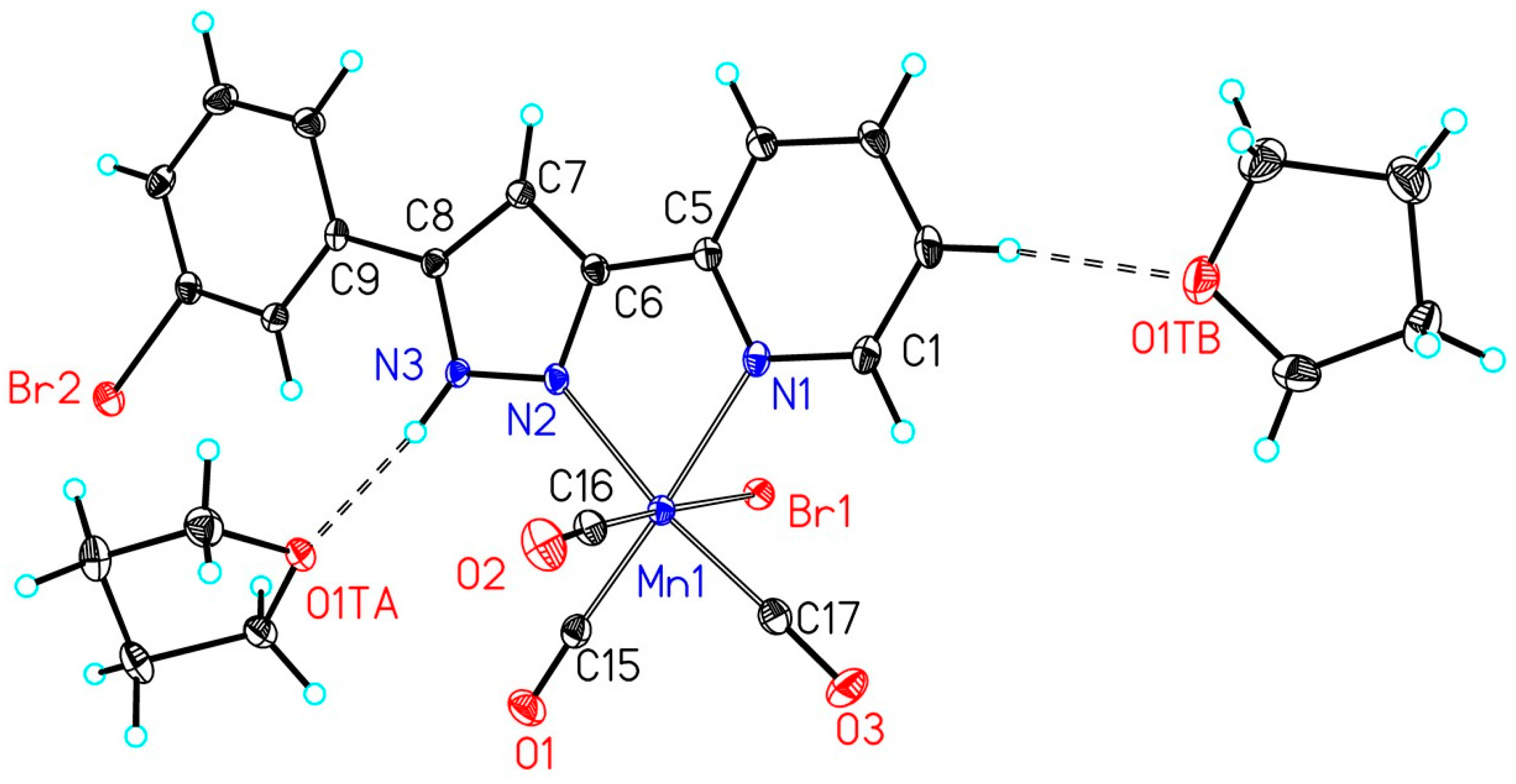

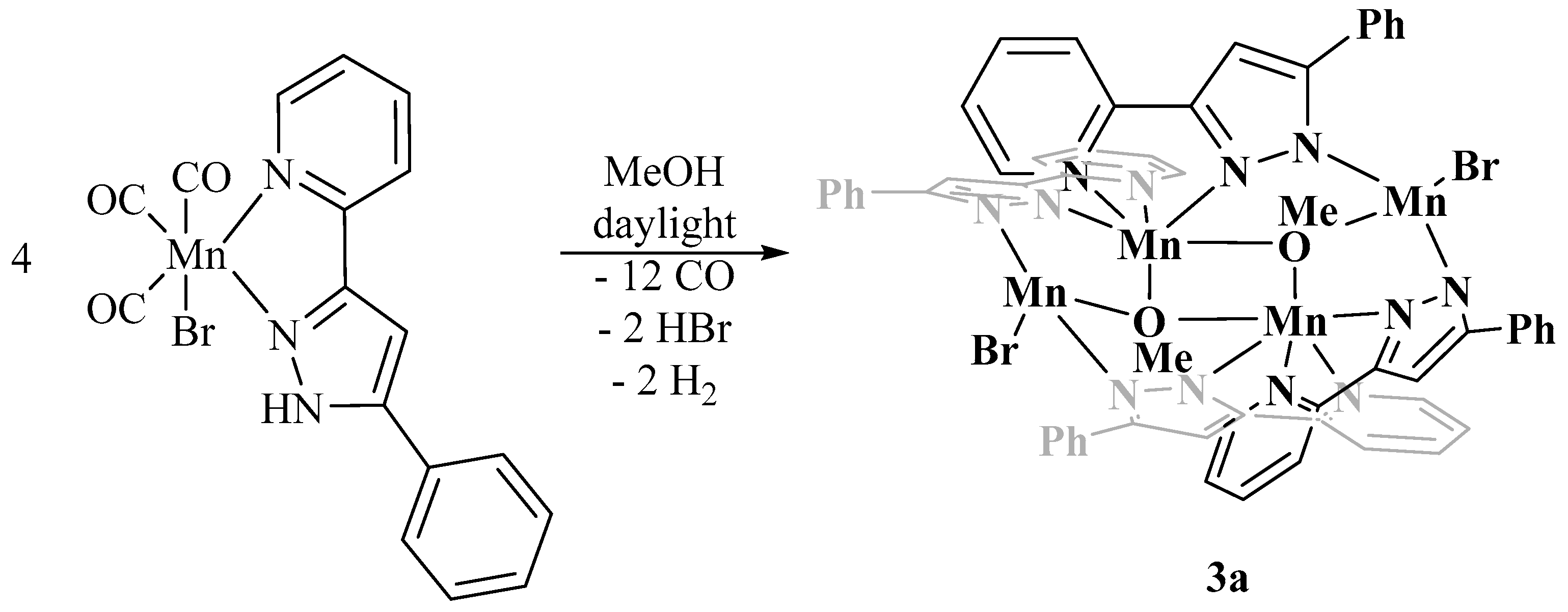

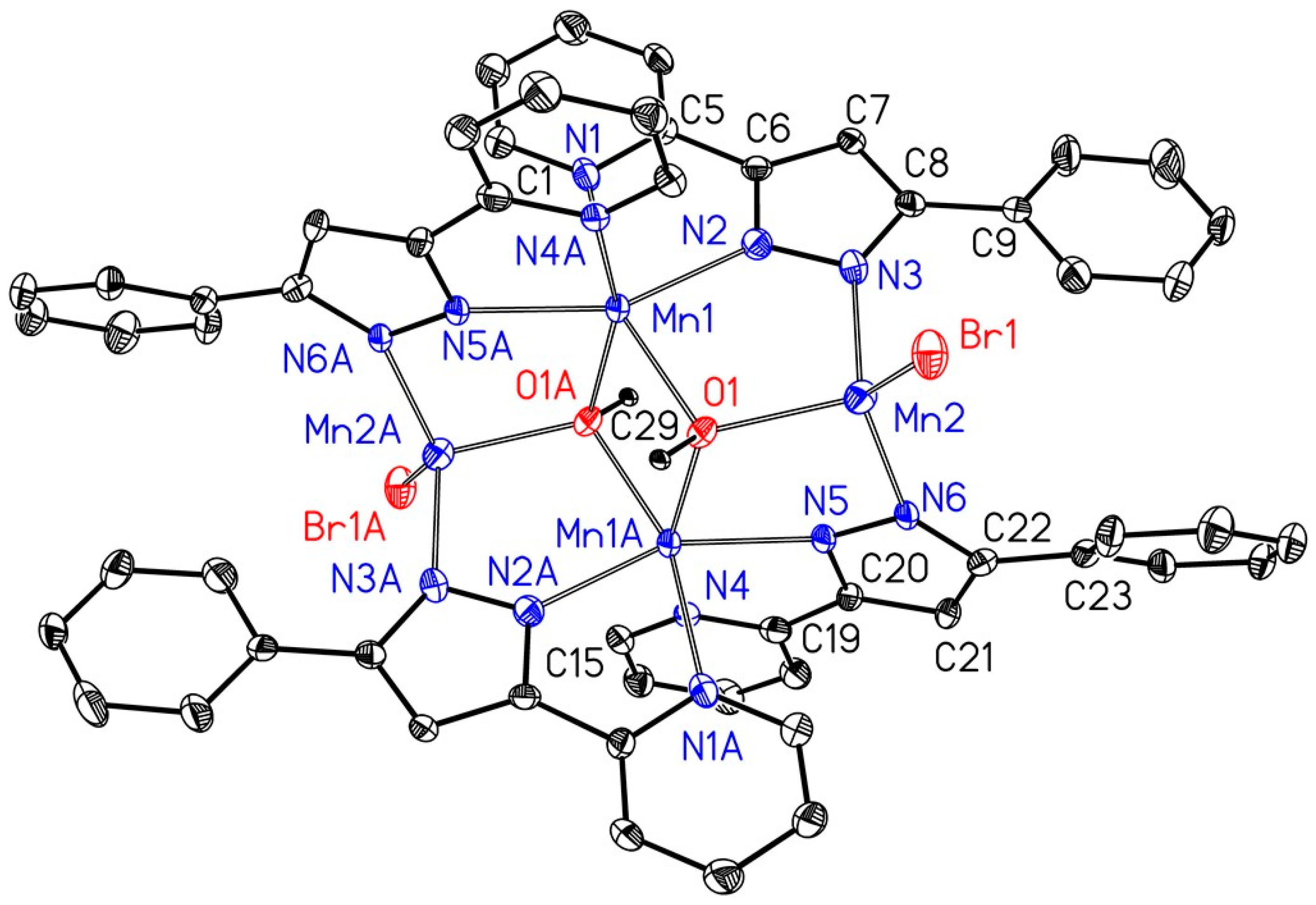

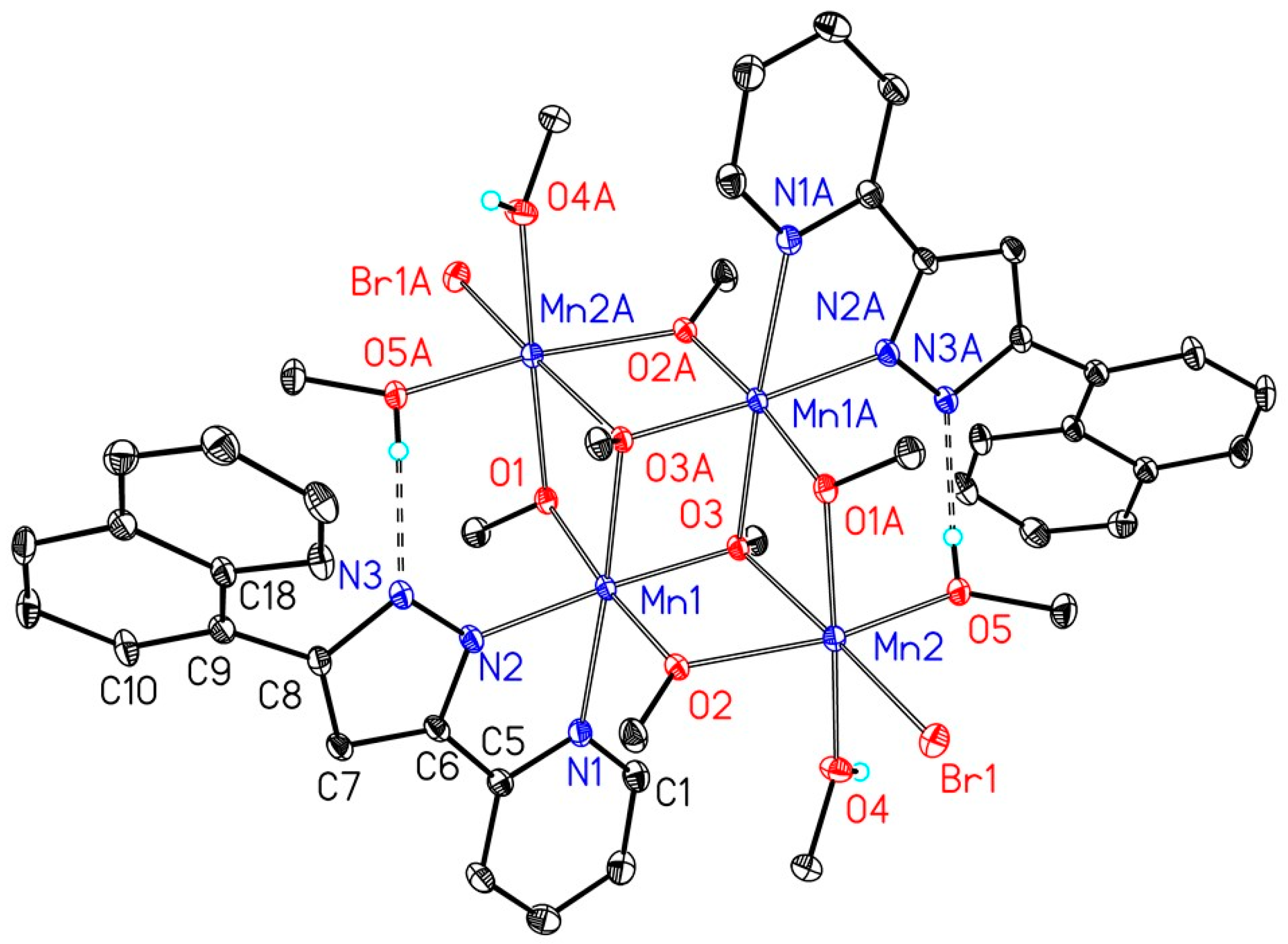

2.2. Degradation of [(OC)3Mn(Br)(2-PyPzRH)] (R = Ph, Naph) in Methanol

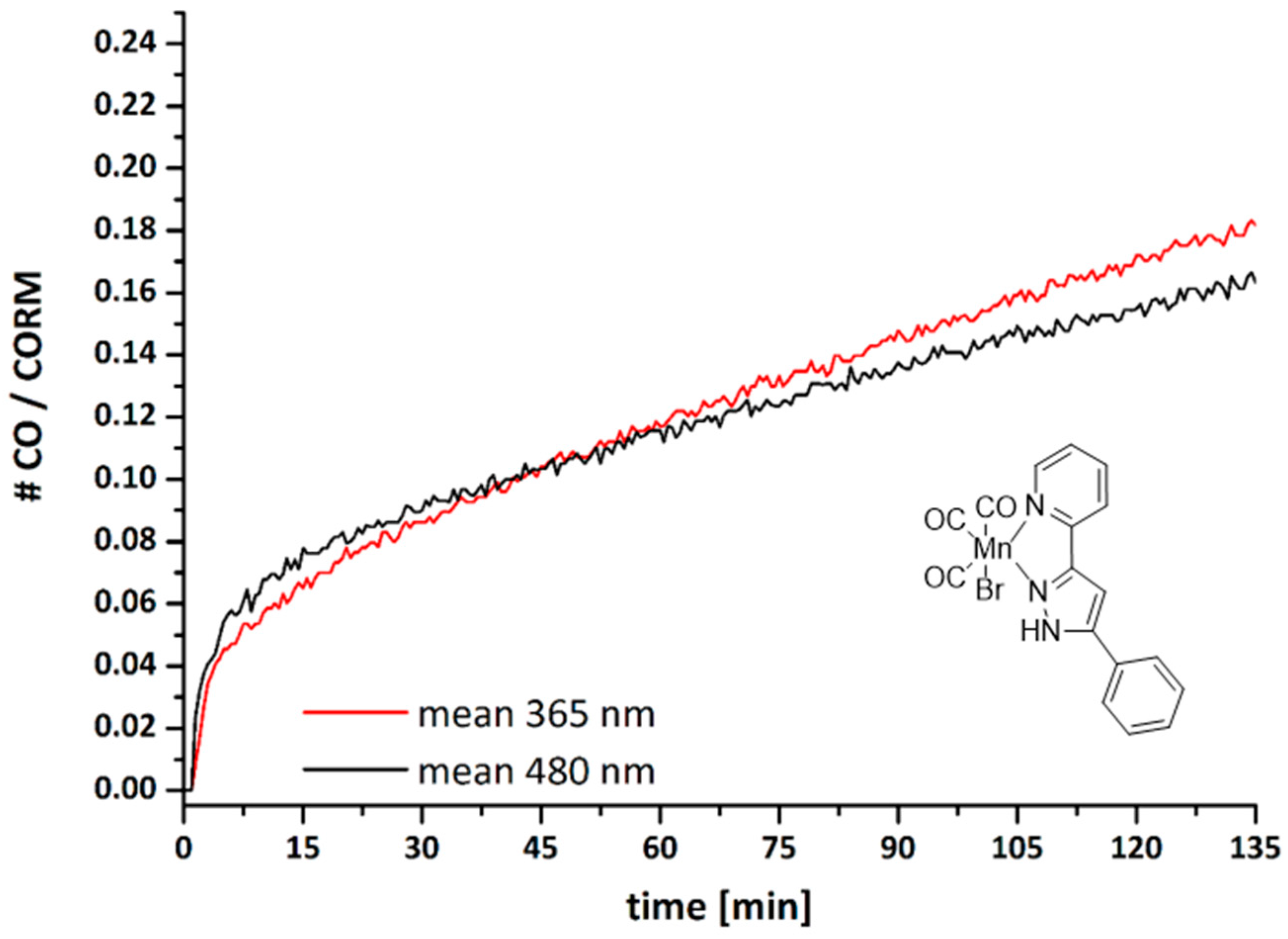

2.3. CO Release from [(OC)3Mn(Br)(2-PyPzPh)] (2)

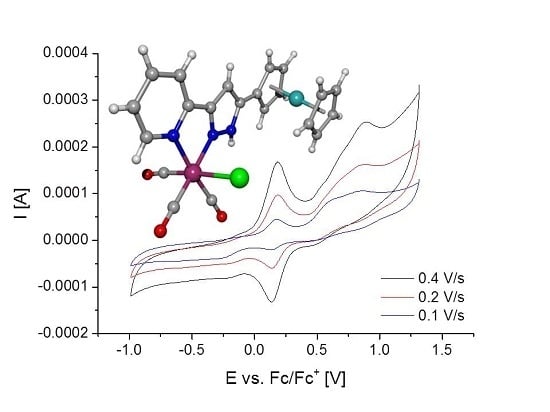

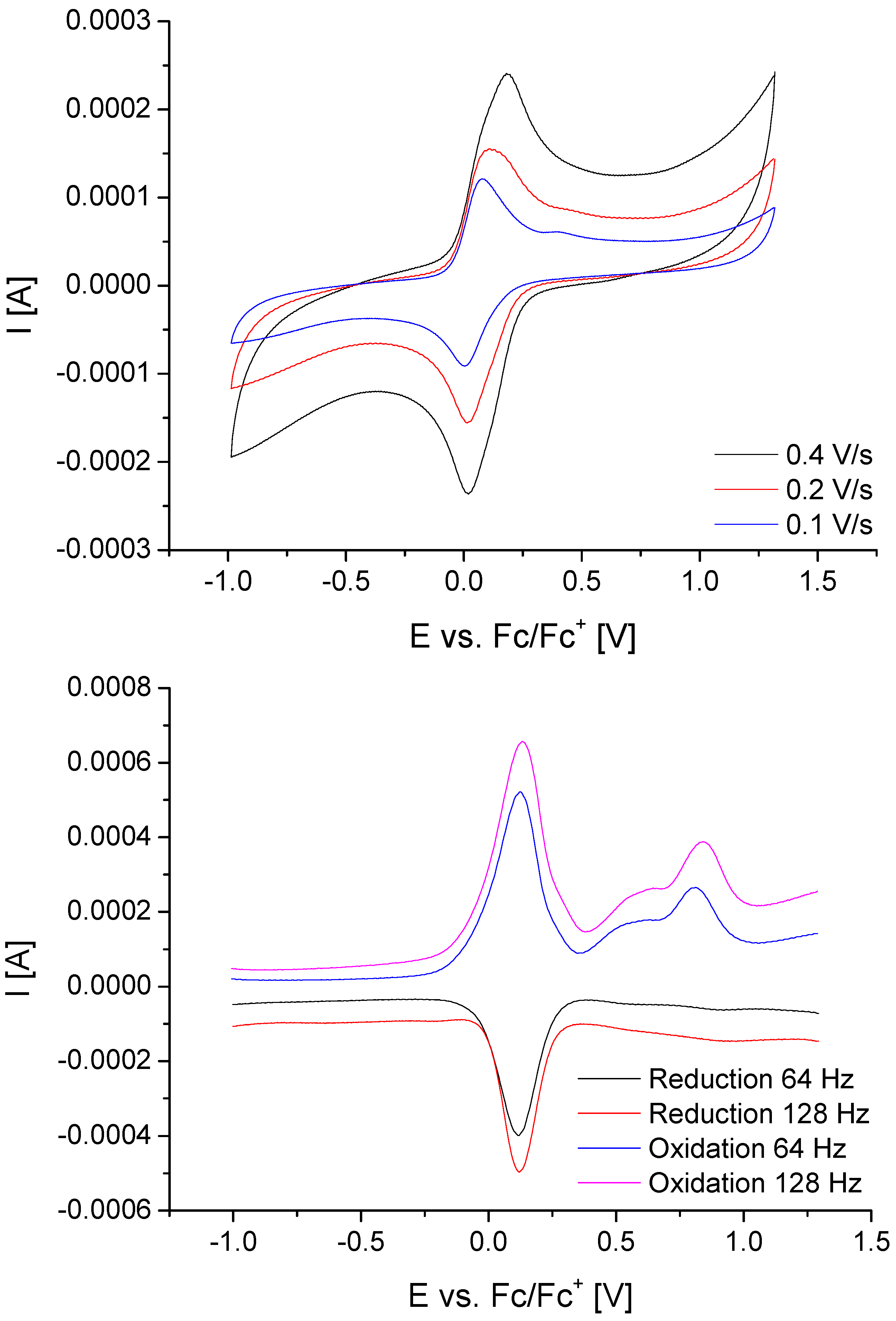

2.4. Electrochemical Studies of [(OC)3Mn(Br)(2-PyPzFc)] (2k)

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. General Remarks

4.2. General Procedures

4.3. X-Ray Structure Determinations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ji, X.; Damera, K.; Zheng, Y.; Yu, B.; Otterbein, L.E.; Wang, B. Toward Carbon Monoxide-Based Therapeutics: Critical Drug Delivery and Development Issues. J. Pharmaceut. Sci. 2016, 105, 406–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marhenke, J.; Trevino, K.; Works, C. The Chemistry, Biology and Design of Photochemical CO Releasing Molecules and the Efforts to detect CO for Biological Applications. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2016, 306, 533–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inaba, H.; Fujita, K.; Ueno, T. Design of Biomaterials for Intracellular Delivery of Carbon Monoxide. Biomater. Sci. 2015, 3, 1423–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schatzschneider, U. Novel Lead Structures and Activation Mechanisms for CO-Releasing Molecules (CORMs). Br. J. Pharmacol. 2015, 172, 1638–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakraborty, I.; Carrington, S.J.; Mascharak, P.K. Design Strategies to Improve the Sensitivity of Photoactive Metal Carbonyl Complexes (photoCORMs) to Visible Light and Their Potential as CO-Donors to Biological Targets. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014, 47, 2603–2611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heinemann, S.H.; Hoshi, T.; Westerhausen, M.; Schiller, A. Carbon Monoxide—Physiology, Detection and Controlled Release. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 3644–3660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Gallego, S.; Bernardes, G.J.L. Carbon-Monoxide-Releasing Molecules for the Delivery of Therapeutic CO in Vivo. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 9712–9721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzales, M.A.; Mascharak, P.K. Photoactive Metal Carbonyl Complexes as Potential Agents for Targeted CO Delivery. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2014, 133, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foresti, R.; Motterlini, R. CO-Releasing Molecules: Avoiding Toxicity and Exploiting the Beneficial Effects of CO for the Treatment of Cardiovascular Disorders. Future Med. Chem. 2013, 5, 367–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zobi, F. CO and CO-releasing Molecules in Medicinal Chemistry. Future Med. Chem. 2013, 5, 175–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romão, C.C.; Blättler, W.A.; Seixas, J.D.; Bernardes, G.J.L. Developing Drug Molecules for Therapy with Carbon Monoxide. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 3571–3583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mann, B.E. CO-releasing Molecules: A Personal View. Organometallics 2012, 31, 5728–5735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimmer, R.D.; Pierri, A.E.; Ford, P.C. Photochemically Activated Carbon Monoxide Release for Biological Targets. Toward Developing Air-Stable photoCORMs Labilized by Visible Light. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2012, 256, 1509–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schatzschneider, U. PhotoCORMs: Light-Triggered Release of Carbon Monoxide from the Coordination Sphere of Transition Metal Complexes for Biological Applications. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2011, 374, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schatzschneider, U. Photoactivated Biological Activity of Transition-Metal Complexes. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2010, 1451–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motterlini, R.; Otterbein, L.E. The Therapeutic Potential of Carbon Monoxide. Nat. Rev. 2010, 9, 728–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mann, B.E. Carbon Monoxide: An Essential Signalling Molecule. Top. Organomet. Chem. 2010, 32, 247–285. [Google Scholar]

- Barry, N.P.E.; Sadler, P.J. Exploration of the Medical Periodic Table: Towards New Targets. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 5106–5131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaim, W.; Schwerderski, B. Bioinorganic Chemistry: Inorganic Elements in the Chemistry of Life: An Introduction and Guide; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Frausto da Silva, J.J.R.; Williams, R.J.P. The Biological Chemistry of the Elements: The Inorganic Chemistry of Life, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Maret, W. Metallomics: A Primer of Integrated Biometal Sciences; Imperial College Press: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, L.G.; Aschner, M. (Eds.) Manganese in Health and Disease; The Royal Society of Chemistry: Cambridge, UK, 2015.

- Mede, R.; Lorett-Velásquez, V.P.; Klein, M.; Görls, H.; Schmitt, M.; Gessner, G.; Heinemann, S.H.; Popp, J.; Westerhausen, M. Carbon Monoxide Release Properties and Molecular Structures of Thiophenolatomanganese(I) Carbonyl Complexes of the Type [(OC)4Mn(µ-S-aryl)]2. Dalton Trans. 2015, 44, 3020–3033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kautz, A.C.; Kunz, P.C.; Janiak, C. CO-Releasing Molecule (CORM) Conjugate Systems. Dalton Trans. 2016, 45, 18045–18063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, D.; Boyer, C. Macromolecular and Inorganic Nanomaterials Scaffolds for Carbon Monoxide Delivery: Recent Developments and Future Trends. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2015, 1, 895–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gläser, S.; Mede, R.; Görls, H.; Seupel, S.; Bohlender, C.; Wyrwa, R.; Schirmer, S.; Dochow, S.; Reddy, G.U.; Popp, J.; et al. Remote-Controlled Delivery of CO via Photoactive CO-Releasing Materials on a Fiber Optical Device. Dalton Trans. 2016, 45, 13222–13233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohlender, C.; Gläser, S.; Klein, M.; Weisser, J.; Thein, S.; Neugebauer, U.; Popp, J.; Wyrwa, R.; Schiller, A. Light-Triggered CO Release from Nanoporous Non-Wovens. J. Mater. Chem. B 2014, 2, 1454–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mede, R.; Klein, M.; Claus, R.A.; Krieck, S.; Quickert, S.; Görls, H.; Neugebauer, U.; Schmitt, M.; Gessner, G.; Heinemann, S.H.; et al. CORM-EDE1: A Highly Water-Soluble and Nontoxic Manganese-Based photoCORM with a Biogenic Ligand Sphere. Inorg. Chem. 2016, 55, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dördelmann, G.; Pfeiffer, H.; Birkner, A.; Schatzschneider, U. Silicium Dioxide Nanoparticles as Carriers for Photoactivatable CO-Releasing Molecules (PhotoCORMs). Inorg. Chem. 2011, 50, 4362–4367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dördelmann, G.; Meinhardt, T.; Sowik, T.; Krueger, A.; Schatzschneider, U. CuAAC Click Functionalization of Azide-Modified Nanodiamond with a Photoactivatable CO-Releasing Molecule (PhotoCORM) Based on [Mn(CO)3(tpm)]+. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 11528–11530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukherjee, R. Coordination Chemistry with Pyrazole-Based Chelating Ligands: Molecular Structural Aspects. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2000, 203, 151–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schowtka, B.; Görls, H.; Westerhausen, M. 3-(1-Adamantyl)-, 3-Ferrocenyl- and 3-(2-Furanyl)-Substituted 5-(2-Pyridyl)pyrazole as Well as Lithium and Zinc Complexes. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 2014, 640, 907–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schowtka, B.; Müller, C.; Görls, H.; Westerhausen, M. Synthesis, Structures and Spectroscopic Properties of 3-Aryl-5-(2-pyridyl)pyrazoles and Related Pyrazoles. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 2014, 640, 916–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Lezama, M.; Höpfl, H.; Zúñiga-Villarreal, N. Tricarbonyl[(1–5-η)-pentadienyl]manganese: A Source of Benzeneselenatomanganese Derivatives of Diverse Nuclearity. Organometallics 2010, 29, 1537–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germán-Acacio, J.M.; Reyes-Lezama, M.; Zúñiga-Villarreal, N. Synthesis and Structural Studies of Phosphorus Carbonyl Manganacycles Containing the Tetraphenyldiselenoimidodiphosphinato Ligand. J. Organomet. Chem. 2006, 691, 3223–3231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, W.A.; Serrano, R.; Weichmann, J. Metallcarbonyl Synthesen XIII. Eine Mangan–Mangan-Dreifachbindung. J. Organomet. Chem. 1983, 246, C57–C60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooft, R. COLLECT, Data Collection Software; Nonius B.V.: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Otwinowski, Z.; Minor, W. Processing of X-Ray Diffraction Data Collected in Oscillation Mode. In Methods in Enzymology, Macromolecular Crystallography; Carter, C.W., Sweet, R.M., Eds.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1997; Part A; Volume 276, pp. 307–326. [Google Scholar]

- SADABS 2.10; Bruker-AXS Inc.: Madison, WI, USA, 2002.

- Sheldrick, G.M. A Short History of SHELX. Acta Cryst. 2008, A64, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spek, A.L. Structure Validation in Chemical Crystallography. Acta Cryst. 2009, D65, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- XP; Siemens Analytical X-ray Instruments Inc.: Karlsruhe, Germany, 1990; Madison, WI, USA, 1994.

- POV-Ray; Persistence of Vision Raytracer: Victoria, Australia, 2007.

| Complex | R 1 | δ(13C CO{1H})/ppm | ν(CO)/cm−1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2a | Ph | 223.5, 223.9 | 2021, 1895 |

| 2b | 1-Naph | 223.8, 223.3, 221.5 | 2026, 1948, 1912 |

| 2c | 2-Anth | n.o.2 | 2023, 1931, 1904 |

| 2d | 1-Pyr | n.o. 2 | 2027, 1930, 1898, 1864 |

| 2e | C6H4-4-Br | 228.5, 226.3 | 2020, 1940, 1906, 1886 |

| 2f | C6H4-3-Br | 223.2, 221.5 | 2024, 1914, 1862, 1838 |

| 2g | C6H-2,3,5,6-Me4 (Dur) | 222.9, 220.6 | 2022, 1940, 1902 |

| 2h | 2-Py | 222.3, 221.2, 220.9 | 2024, 1932, 1892 |

| 2i | 2-Fu | n.o. 2 | 2024, 1933, 1895 |

| 2j | 2-Thi | n.o. 2 | 2020, 1910 |

| 2k | Fc | 224.1, 223.5, 221.9 | 2023, 1931, 1911, 1866 |

| 2l | 1-Ad | n.o. 2 | 2030, 1943, 1913, 1893 |

| Complex | Mn1–Br1 | Mn1–CtransPy | Mn1–CtransPz | Mn1–CtransBr | Mn1–NPy | Mn1–NPz |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2a | 252.43(5) | 182.2(3) | 181.5(3) | 186.5(3) | 208.2(2) | 202.9(2) |

| 2b | 254.00(11) | 180.9(6) | 181.3(6) | 180.9(6) | 207.9(5) | 202.4(5) |

| 2e | 254.20(5) | 181.3(3) | 180.7(3) | 180.3(3) | 208.2(2) | 203.1(2) |

| 2f | 253.86(4) | 182.0(3) | 179.9(3) | 179.7(3) | 206.9(2) | 201.9(2) |

| 2g | 254.97(4) | 181.0(2) | 181.4(2) | 180.6(2) | 207.60(16) | 203.58(16) |

| 2h | 253.78(4) | 182.4(2) | 180.4(2) | 180.6(2) | 208.32(17) | 202.83(17) |

| 2i | 255.38(4) | 181.5(2) | 181.0(2) | 180.4(2) | 207.72(19) | 203.36(19) |

| 2j | 255.66(4) | 181.8(3) | 181.0(3) | 181.2(3) | 207.8(2) | 202.20(18) |

| 2k | 254.78(9) | 181.4(5) | 180.5(5) | 181.5(5) | 206.8(4) | 201.7(4) |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mede, R.; Gläser, S.; Suchland, B.; Schowtka, B.; Mandel, M.; Görls, H.; Krieck, S.; Schiller, A.; Westerhausen, M. Manganese(I)-Based CORMs with 5-Substituted 3-(2-Pyridyl)Pyrazole Ligands. Inorganics 2017, 5, 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/inorganics5010008

Mede R, Gläser S, Suchland B, Schowtka B, Mandel M, Görls H, Krieck S, Schiller A, Westerhausen M. Manganese(I)-Based CORMs with 5-Substituted 3-(2-Pyridyl)Pyrazole Ligands. Inorganics. 2017; 5(1):8. https://doi.org/10.3390/inorganics5010008

Chicago/Turabian StyleMede, Ralf, Steve Gläser, Benedikt Suchland, Björn Schowtka, Miles Mandel, Helmar Görls, Sven Krieck, Alexander Schiller, and Matthias Westerhausen. 2017. "Manganese(I)-Based CORMs with 5-Substituted 3-(2-Pyridyl)Pyrazole Ligands" Inorganics 5, no. 1: 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/inorganics5010008