Methodological Issues in Antifungal Susceptibility Testing of Malassezia pachydermatis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Current Status of Antifungal Susceptibility Testing Methods

3. Antifungal Susceptibility Testing of Malassezia pachydermatis

3.1. The Test Conditions

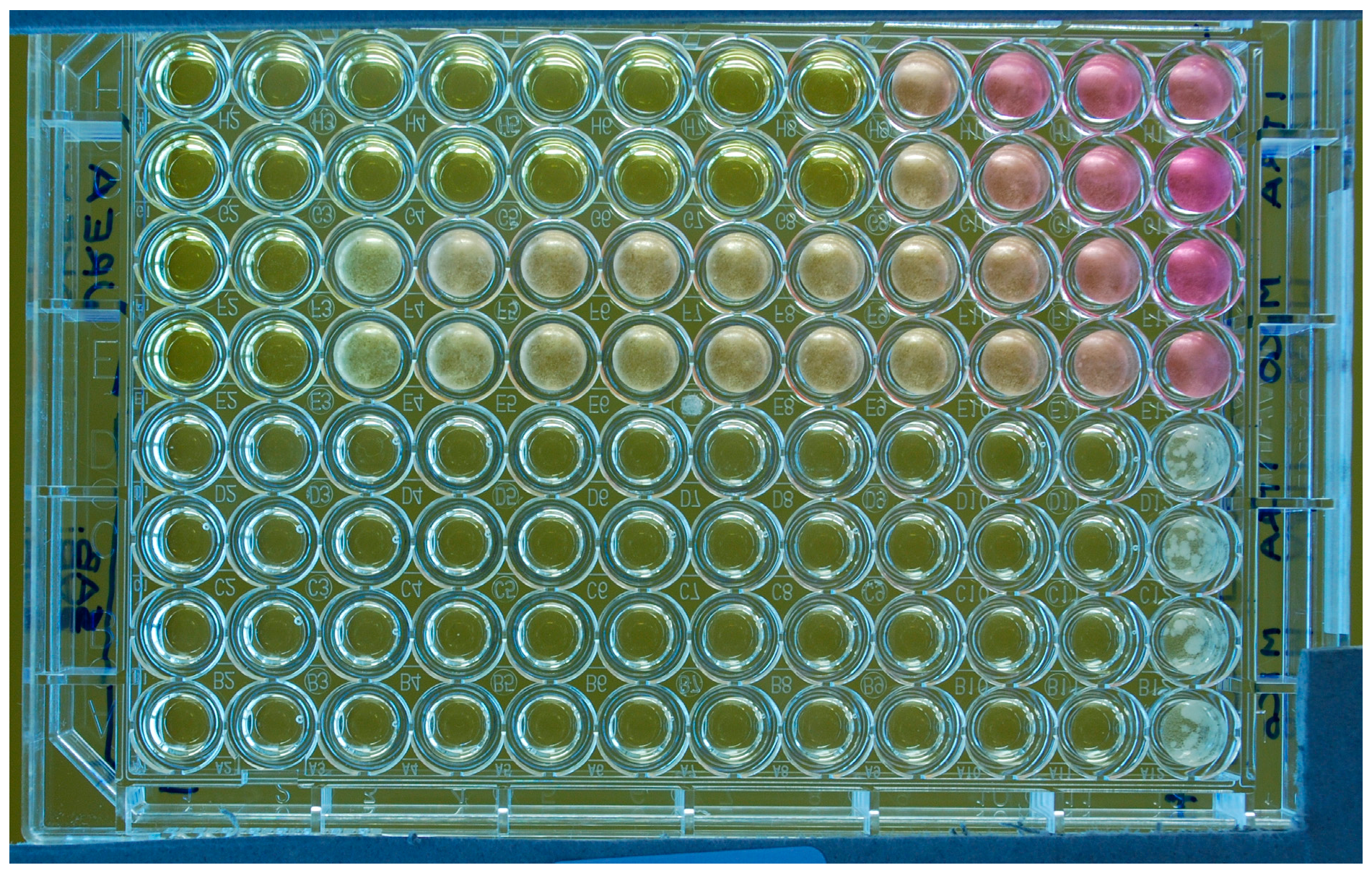

3.1.1. The Growth Medium in Broth-Based Techniques

3.1.2. The Growth Medium in Agar Dilution Assays

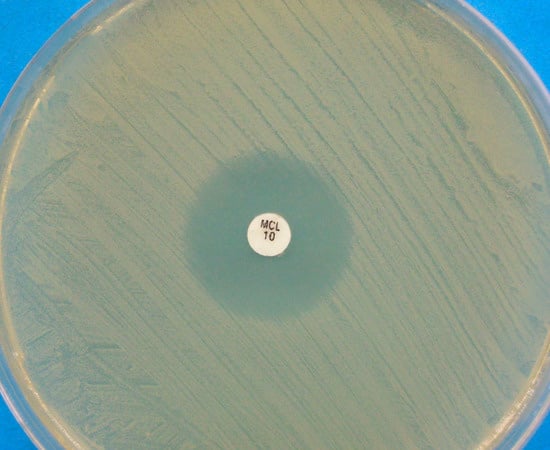

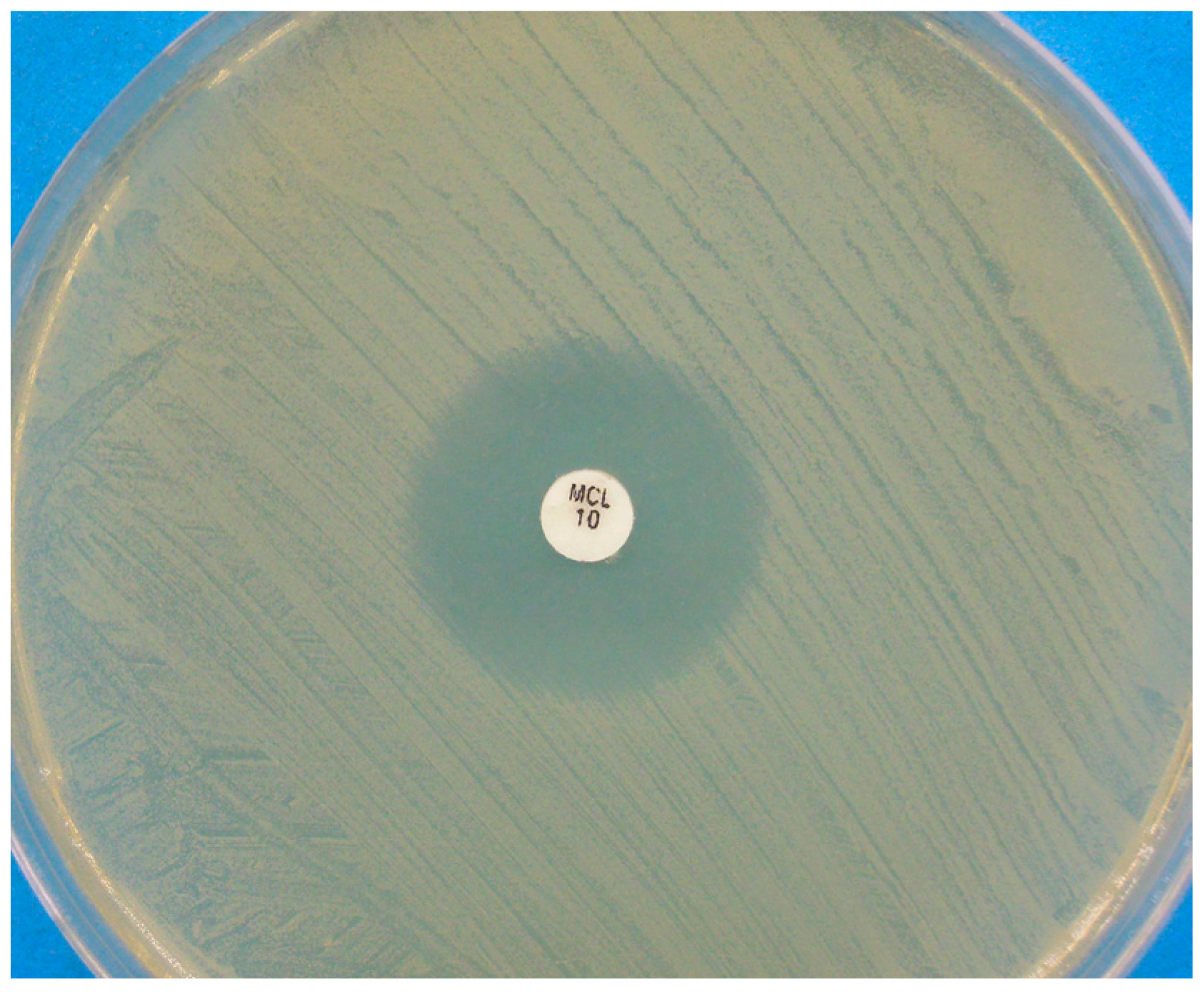

3.1.3. The Growth Medium in Agar Diffusion Assays

3.1.4. The Inoculum Preparation

3.1.5. Temperature and Length of Incubation

3.1.6. The Method of End-Point Determination in Broth- and Agar-Dilution Assays

3.1.7. The Quality Controls (QC)

4. Conclusions and Perspectives

Supplementary Materials

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bond, R.; Guillot, J.; Cabanes, J. Malassezia yeasts in animal diseases. In Malassezia and the Skin; Boekhout, T., Mayser, P., Velegraki, A., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2010; pp. 271–299. [Google Scholar]

- Gaitanis, G.; Magiatis, P.; Hantschke, M.; Bassukas, I.D.; Velegraki, A. The Malassezia genus in skin and systemic diseases. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2012, 25, 106–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, T.A.; Hill, P.B. The biology of Malassezia organisms and their ability to induce immune responses and skin disease. Vet. Dermatol. 2005, 16, 4–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, D.W.; Miller, W.H.; Griffin, C.E. Malassezia dermatitis. In Muller and Kirk’s Small Animal Dermatology, 7th ed.; WB Saunders Co.: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2013; pp. 243–249. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, D.W.; Miller, W.H.; Griffin, C.E. Otitis externa. In Muller and Kirk’s Small Animal Dermatology, 7th ed.; WB Saunders Co.: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2013; pp. 741–773. [Google Scholar]

- Bond, R. Malassezia dermatitis. In Infectious Diseases of the Dog and Cat; WB Saunders Co.: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2006; pp. 565–569. [Google Scholar]

- Greene, C.E. Antifungal chemotherapy. In Infectious Diseases of the Dog and Cat; Greene, C.E., Ed.; WB Saunders Co.: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2006; pp. 542–550. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, D.W.; Miller, W.H.; Griffin, C.E. Antifungal therapy. In Muller and Kirk’s Small Animal Dermatology, 7th ed.; WB Saunders Co.: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2013; pp. 225–231. [Google Scholar]

- Negre, A.; Bensignor, E.; Guillot, J. Evidence-based veterinary dermatology: A systematic review of interventions for Malassezia dermatitis in dogs. Vet. Dermatol. 2009, 20, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, I.L.; Chiu, N.C.; Chi, H.; Hsu, C.H.; Chang, J.H.; Huang, D.T.; Huang, F.Y. Changing of bloodstream infections in a medical center neonatal intensive care unit. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chryssanthou, E.; Broberger, U.; Petrini, B. Malassezia pachydermatis fungaemia in a neonatal intensive care unit. Acta Paediatr. 2001, 90, 323–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gueho, E.; Simmons, R.B.; Pruitt, W.R.; Meyer, S.A.; Ahearn, D.G. Association of Malassezia pachydermatis with systemic infections of humans. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1987, 25, 1789–1790. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chang, H.J.; Miller, H.L.; Watkins, N.; Arduino, M.J.; Ashford, D.A.; Midgley, G.; Aguero, S.M.; Pinto-Powell, R.; von Reyn, C.F.; Edwards, W.; et al. An epidemic of Malassezia pachydermatis in an intensive care nursery associated with colonization of health care workers’ pet dogs. N. Engl. J. Med. 1998, 338, 706–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Sweih, N.; Ahmad, S.; Joseph, L.; Khan, S.; Khan, Z. Malassezia pachydermatis fungemia in a preterm neonate resistant to fluconazole and flucytosine. Med. Mycol. Case Rep. 2014, 5, 9–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cafarchia, C.; Figueredo, L.A.; Iatta, R.; Montagna, M.T.; Otranto, D. In vitro antifungal susceptibility of Malassezia pachydermatis from dogs with and without skin lesions. Vet. Microbiol. 2012, 155, 395–398. [Google Scholar]

- Cafarchia, C.; Figueredo, L.A.; Iatta, R.; Colao, V.; Montagna, M.T.; Otranto, D. In Vitro evaluation of Malassezia pachydermatis susceptibility to azole compounds using E-test and CLSI microdilution methods. Med. Mycol. 2012, 50, 795–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jesus, F.P.K.; Lautert, C.; Zanette, R.A.; Mahl, D.L.; Azevedo, M.I.; Machado, M.L.S.; Dutra, V.; Botton, S.A.; Alves, S.H.; Santurio, J.M. In Vitro susceptibility of fluconazole-susceptible and -resistant isolates of Malassezia pachydermatis against azoles. Vet. Microbiol. 2011, 152, 161–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nascente, P.S.; Meinerz, A.R.M.; de Faria, R.O.; Schuch, L.F.D.; Meireles, M.C.A.; de Mello, J.R.B. CLSI broth microdilution method for testing susceptibility of Malassezia pachydermatis to thiabendazole. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2009, 40, 222–226. [Google Scholar]

- Nascente, P.S.; Nobre, M.O.; Schuch, L.F.; Lucia-Júnior, T.; Ferreiro, L.; Meireles, M.C.A. Evaluation of Malassezia pachydermatis antifungal susceptibility using two different methods. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2003, 34, 359–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rougier, S.; Borell, D.; Pheulpin, S.; Woehrlé, F.; Boisramé, B. A comparative study of two antimicrobial/anti-inflammatory formulations in the treatment of canine otitis externa. Vet. Dermatol. 2005, 16, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rambali, B.; Fernandez, J.A.; van Nuffel, L.; Woestenborghs, F.; Baert, L.; Massart, D.L.; Odds, F.C. Susceptibility testing of pathogenic fungi with itraconazole: A process analysis of test variables. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2001, 48, 163–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rex, J.H.; Pfaller, M.A. Has antifungal susceptibility testing come of age? Clin. Infect. Dis. 2002, 35, 982–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfaller, M.A. Antifungal drug resistance: Mechanisms, epidemiology, and consequences for treatment. Am. J. Med. 2012, 125, S3–S13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, E.M. Issues in antifungal susceptibility testing. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2008, 61, i13–i18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute. CLSI Document M27-A3: Reference Method for Broth Dilution Antifungal Susceptibility Testing of Yeasts, Approved Standard, 3rd ed.; CLSI: Wayne, PA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute. Reference Method for Broth Dilution Antifungal Susceptibility Testing of Yeasts, Fourth Informational Supplement; CLSI: Wayne, PA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cantón, E.; Espinel-Ingroff, A.; Pemán, J. Trends in antifungal susceptibility testing using CLSI reference and commercial methods. Expert Rev. Anti. Infect. Ther. 2009, 7, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arikan, S. Current status of antifungal susceptibility testing methods. Med. Mycol. 2007, 45, 569–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute. CLSI Document M44-A2: Reference Method for Antifungal Disk Diffusion Susceptibility Testing of Yeasts, Approved Guideline, 2nd ed.; CLSI: Wayne, PA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Subcommittee of the ESCMID/EUCAST. EUCAST definitive document EDef 7.1: Method for the determination of broth dilution MICs of antifungal agents for fermentative yeasts. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2008, 14, 398–405. [Google Scholar]

- Arendrup, M.C.; Cuenca-Estrella, M.; Lass-Flörl, C.; Hope, W.; the EUCAST-AFST. EUCAST technical note on the EUCAST definitive document EDef 7.2: Method for the determination of broth dilution minimum inhibitory concentrations of antifungal agents for yeasts EDef 7.2 (EUCAST-AFST). Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2012, 18, 246–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfaller, M.A.; Andes, D.; Diekema, D.J.; Espinel-Ingroff, A.; Sheehan, D. CLSI Subcommittee for Antifungal Susceptibility Testing. Wild-type MIC distributions, epidemiological cutoff values and species-specific clinical breakpoints for fluconazole and Candida: Time for harmonization of CLSI and EUCAST broth microdilution methods. Drug Resist. Updat. 2010, 13, 180–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cafarchia, C.; Figueredo, L.A.; Favuzzi, V.; Surico, M.R.; Colao, V.; Iatta, R.; Otranto, D. Assessment of the antifungal susceptibility of Malassezia pachydermatis in various media using a CLSI protocol. Vet. Microbiol. 2012, 159, 536–540. [Google Scholar]

- Peano, A.; Beccati, M.; Chiavassa, E.; Pasquetti, M. Evaluation of the antifungal susceptibility of Malassezia pachydermatis to clotrimazole, miconazole and thiabendazole using a modified CLSI M27-A3 microdilution method. Vet. Dermatol. 2012, 23, 131–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Álvarez-Pérez, S.; García, M.E.; Peláez, T.; Blanco, J.L. Genotyping and antifungal susceptibility testing of multiple Malassezia pachydermatis isolates from otitis and dermatitis cases in pets: Is it really worth the effort? Med. Mycol. 2016, 54, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bernardo, F.M.; Martins, H.M.; Martins, M.L. A survey of mycotic otitis externa of dogs in Lisbon. Rev. Iberoam. Micol. 1998, 15, 163–165. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Brito, E.H.S.; Fontenelle, R.O.S.; Brilhante, R.S.N.; Cordeiro, R.A.; Monteiro, A.J.; Sidrim, J.J.C. The anatomical distribution and antimicrobial susceptibility of yeast species isolated from healthy dogs. Vet. J. 2009, 182, 320–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brito, E.H.S.; Fontenelle, R.O.S.; Brilhante, R.S.N.; Cordeiro, R.A.; Soares Júnior, F.A.; Monteiro, A.J. Phenotypic characterization and in vitro antifungal sensitivity of Candida spp. and Malassezia pachydermatis strains from dogs. Vet. J. 2007, 174, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cafarchia, C.; Iatta, R.; Immediato, D.; Puttilli, M.R.; Otranto, D. Azole susceptibility of Malassezia pachydermatis and Malassezia furfur and tentative epidemiological cut-off values. Med. Mycol. 2015, 53, 743–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiavassa, E.; Tizzani, P.; Peano, A. In vitro antifungal susceptibility of Malassezia pachydermatis strains isolated from dogs with chronic and acute otitis externa. Mycopathologia 2014, 178, 315–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coutinho, S.D.; Paula, C.R. Susceptibility to antifungal agents of Malassezia pachydermatis isolates from dogs. Pol. J. Vet. Sci. 2001, 4, 77–81. [Google Scholar]

- Eichenberg, M.; Appelt, C.E.; Berg, V.; Cunha Muschner, A.; de Oliveira Nobre, M.; da Matta, D.; Alves, S.; Ferreiro, L. Susceptibility of Malassezia pachydermatis to azole antifungal agents evaluated by a new broth microdilution method. Acta Sci. Vet. 2003, 31, 75–80. [Google Scholar]

- Garau, M.; Pereiro, M.; del Palacio, A. In vitro susceptibilities of Malassezia species to a new triazole, albaconazole (UR-9825), and other antifungal compounds. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2003, 47, 2342–2344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon, M.A.; Lapa, E.W.; Passero, P.G. Improved method for azole antifungal susceptibility testing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1988, 26, 1874–1877. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gupta, A.K.; Kohli, Y.; Li, A.; Faergemann, J.; Summerbell, R.C. In Vitro susceptibility of the seven Malassezia species to ketoconazole, voriconazole, itraconazole and terbinafine. Br. J. Dermatol. 2000, 142, 758–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hensel, P.; Austel, M.; Wooley, R.E.; Keys, D.; Ritchie, B.W. In Vitro and in vivo evaluation of a potentiated miconazole aural solution in chronic Malassezia otitis externa in dogs. Vet. Dermatol. 2009, 20, 429–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiss, G.; Radványi, S.; Szigeti, G. New combination for the therapy of canine otitis externa I microbiology of otitis externa. J. Small Anim. Pract. 1997, 38, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorenzini, R.; Mercantini, R.; de Bernardis, F. In vitro sensitivity of Malassezia spp. to various antimycotics. Drugs Exp. Clin. Res. 1985, 11, 393–395. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lyskova, P.; Vydrzalova, M.; Mazurova, J. Identification and antimicrobial susceptibility of bacteria and yeasts isolated from healthy dogs and dogs with otitis externa. J. Vet. Med. A Physiol. Pathol. Clin. Med. 2007, 54, 559–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murai, T.; Nakamura, Y.; Kano, R.; Watanabe, S.; Hasegawa, A. Susceptibility testing of Malassezia pachydermatis using the urea broth microdilution method. Mycoses 2002, 45, 84–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, Y.; Kano, R.; Murai, T.; Watanabe, S.; Hasegawa, A. Susceptibility testing of Malassezia species using the urea broth microdilution method. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2000, 44, 2185–2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakano, Y.; Wada, M.; Tani, H.; Sasai, K.; Baba, E. Effects of β-thujaplicin on anti-Malassezia pachydermatis remedy for canine otitis externa. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2005, 67, 1243–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nascente, P.S.; Cleff, M.B.; Meinerz, A.R.M.; Xavier, M.O.; Schuch, L.F.D.; Meireles, M.C.A.; Braga de Mello, J.R. Comparison of the broth microdilution technique and ETEST to ketoconazole front Malassezia pachydermatis. Braz. J. Vet. Res. Anim. Sci. 2009, 46, 222–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijima, M.; Kano, R.; Nagata, M.; Hasegawa, A.; Kamata, H. An azole-resistant isolate of Malassezia pachydermatis. Vet. Microbiol. 2011, 149, 288–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasquetti, M.; Chiavassa, E.; Tizzani, P.; Danesi, P.; Peano, A. Agar diffusion procedures for susceptibility testing of Malassezia pachydermatis: Evaluation of Mueller–Hinton agar plus 2% glucose and 0.5 µg/mL methylene blue as the test medium. Mycopathologia 2015, 180, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pietschmann, S.; Hoffmann, K.; Voget, M.; Pison, U. Synergistic effects of miconazole and polymyxin B on microbial pathogens. Vet. Res. Commun. 2009, 33, 489–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prado, M.R.; Brito, E.H.S.; Brilhante, R.S.N.; Cordeiro, R.A.; Leite, J.J.G.; Sidrim, J.J.C. Subculture on potato dextrose agar as a complement to the broth microdilution assay for Malassezia pachydermatis. J. Microbiol. Methods 2008, 75, 341–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rincón, S.; Cepero de García, M.C.; Espinel-Ingroff, A. A modified Christensen’s urea and CLSI broth microdilution method for testing susceptibilities of six Malassezia species to voriconazole, itraconazole, and ketoconazole. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2006, 44, 3429–3431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, A. In vitro activity of climbazole, clotrimazole and silver-sulphadiazine against isolates of Malassezia pachydermatis. Zentralbl. Veterinarmed. B 1997, 44, 193–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugita, T.; Tajima, M.; Ito, T.; Saito, M.; Tsuboi, R.; Nishikawa, A. Antifungal activities of tacrolimus and azole agents against the eleven currently accepted Malassezia species. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2005, 43, 2824–2829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uchida, Y.; Nakade, T.; Kitazawa, K. In Vitro activity of five antifungal agents against Malassezia pachydermatis. Nihon Juigaku Zasshi 1990, 52, 851–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velegraki, A.; Alexopoulos, E.C.; Kritikou, S.; Gaitanis, G. Use of fatty acid RPMI 1640 media for testing susceptibilities of eight Malassezia species to the new triazole posaconazole and to six established antifungal agents by a modified NCCLS M27-A2 microdilution method and Etest. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2004, 42, 3589–3593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe, S.; Koike, A.; Kano, R.; Nagata, M.; Chen, C.; Hwang, C.Y. In Vitro susceptibility of Malassezia pachydermatis isolates from canine skin with atopic dermatitis to ketoconazole and itraconazole in East Asia. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2014, 76, 579–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiler, C.B.; de Jesus, F.P.K.; Nardi, G.H.; Loreto, E.S.; Santurio, J.M.; Coutinho, S.D. Susceptibility variation of Malassezia pachydermatis to antifungal agents according to isolate source. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2013, 44, 174–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weseler, A.; Geiss, H.K.; Saller, R.; Reichling, J. Antifungal effect of Australian tea tree oil on Malassezia pachydermatis isolated from canines suffering from cutaneous skin disease. Schweiz. Arch. Tierheilkd. 2002, 144, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guého, E.; Midgley, G.; Guillot, J. The genus Malassezia with description of four new species. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 1996, 69, 337–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoeprich, P.D.; Finn, P.D. Obfuscation of the activity of antifungal antimicrobics by culture media. J. Infect. Dis. 1972, 126, 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoeprich, P.D.; Huston, A.C. Effect of culture media on the antifungal activity of miconazole and amphotericin B methyl ester. J. Infect. Dis. 1976, 134, 336–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tatsumi, Y.; Yokoo, M.; Arika, T.; Yamaguchi, H. In Vitro antifungal activity of KP-103, a novel triazole derivative, and its therapeutic efficacy against experimental plantar tinea pedis and cutaneous candidiasis in guinea pigs. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2001, 45, 1493–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murai, T.; Nakamura, Y.; Kano, R.; Watanabe, S.; Hasegawa, A. Homogeneous cell suspension of Malassezia pachydermatis obtained with an ultrasonic homogenizer. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2002, 64, 381–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rex, J.H.; Pfaller, M.A.; Walsh, T.J.; Chaturvedi, V.; Espinel-Ingroff, A.; Ghannoum, M.A. Antifungal susceptibility testing: Practical aspects and current challenges. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2001, 14, 643–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arthington-Skaggs, B.A.; Lee-Yang, W.; Ciblak, M.A.; Frade, J.P.; Brandt, M.E.; Hajjeh, R.A. Comparison of visual and spectrophotometric methods of broth microdilution MIC end point determination and evaluation of a sterol quantitation method for in vitro susceptibility testing of fluconazole and itraconazole against trailing and nontrailing Candida isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2002, 46, 2477–2481. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Palacin, C.; Tarragó, C.; Ortiz, J.A. In Vitro activity of sertaconazole against Malassezia furfur and pachydermatis in different culture media. Methods Find. Exp. Clin. Pharmacol. 1998, 20, 451–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameter | Broth-Method | Disk-Diffusion Method |

|---|---|---|

| Test medium | Roswell Park Memorial Institute Medium (RPMI-1640) with glutamine, without bicarbonate. Glucose concentration: 0.2% (EUCAST 2%) | Mueller-Hinton agar + 2% glucose + 0.5 mg/L methylene blue |

| Inoculum size | 0.5 × 103–2.5 × 103 CFU/mL (EUCAST 1 × 105–5 × 105) | 0.5 Mc Farland standard (1 × 106 to 5 × 106 CFU/mL) |

| Microdilution plates | 96 U-shaped wells (EUCAST flat-bottom wells) | NA |

| Temperature and incubation time | Candida spp., 48 h a at 35 °C (EUCAST 24 h) Cryptococcus neoformans, 72 h at 35 °C | 35 °C for 20–24 h Some strains of Candida glabrata, Candida krusei, and Candida parapsilosis often require 48 h |

| Reading method | Visual (EUCAST Spectrophotometric 530 nm) | Measurement of zone size |

| Drug | Ref. | Format | N° | Range | MIC50 | MIC90 | CBS 1879 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMB | Prado et al. (2008) [57] | BMD | 50 | ND | ND | 2 a | Not tested |

| Brito et al. (2009) [37] | BMD | 20 | 0.25 b | 0.25 | 0.25 | Not tested | |

| Velegraki et al. (2004) [62] | BMD | 1 | 0.12 b | NA | NA | Not tested | |

| E-test | 1 | 0.5 b | NA | NA | Not tested | ||

| Brito et al. (2007) [38] | AD | 32 | 0.125–8 | 0.5 | 8 | Not tested | |

| MCZ | Uchida et al. (1990) [61] | BMD | 42 | 0.16–>80 | 1.25 | 20 | 2.5 |

| Gordon et al. (1988) [44] | BMD | 7 | 0.009–0.039 | ND | ND | Not tested | |

| Pietschmann et al. (2008) [56] | BMD | 1 | 2.92 | NA | NA | 2.92 | |

| Hensel et al. (2009) [46] | BMD | 24 | 0.03–0.5 | 0.125 | 0.25 | Not tested | |

| Peano et al. (2012) [34] | BMD | 51 | 0.03–16 | 2 | 4 | Not tested | |

| ITZ | Murai et al. (2002) [50] | BMD | 24 | 1.6 b | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 |

| Garau et al. (2003) [43] | BMD | 10 | ≤0.03–0.06 | ≤0.03 | 0.06 | Not tested | |

| Eichenberg et al. (2003) [42] | BMD | 82 | 0.007–0.125 | 0.06 | 0.125 | Not tested | |

| Rincon et al. (2006) [58] | BMD | 3 | 0.03–0.125 | NA | NA | 0.06 | |

| Prado et al. (2008) [57] | BMD | 50 | ND | ND | <0.03 a | Not tested | |

| Brito et al. (2009) [37] | BMD | 20 | ≤0.03–0.25 | ≤0.03 | ≤0.03 | Not tested | |

| Jesus et al. (2011) [17] | BMD | 30 | 0.01–1 | 0.125 | 0.5 | Not tested | |

| Nascente et al. (2003) [19] | BMD | 24 | 0.03–4 | 0.125 | 0.5 | Not tested | |

| E-test | 35 | 0.002–2 | 0.003 | 0.016 | Not tested | ||

| Velegraki et al. (2004) [62] | BMD | 1 | 0.06 b | NA | NA | Not tested | |

| E-test | 1 | 0.12 b | NA | NA | Not tested | ||

| Nijma et al. (2011) [54] | BMD | 30 | <0.03–2 | <0.03 | <0.03 | <0.03 | |

| E-test | 30 | <0.03–8 | <0.03 | <0.03 | <0.03 | ||

| Nakamura et al. (2000) [51] | BMD | 12 | 0.8–6.3 | ND | ND | Not tested | |

| AD | 12 | 0.4–6.3 | ND | ND | Not tested | ||

| Gupta et al. (2000) [45] | AD | 4 | ≤0.03 b | NA | NA | ≤0.03 | |

| Sugita et al. (2005) [60] | AD | 6 | 0.016 b | NA | NA | Not tested | |

| Brito et al. (2007) [38] | AD | 32 | ≤0.0075 b | ≤0.0075 | ≤0.0075 | Not tested | |

| TER | Murai et al. (2002) [50] | BMD | 24 | 3.2 b | 3.2 | 3.2 | 3.2 |

| Weseler et al. (2002) [65] | BMD | 9 | 0.2–1.6 | NA | NA | Not tested | |

| Velegraki et al. (2004) [62] | BMD | 1 | 0.12 | NA | NA | Not tested | |

| E-test | 1 | NA c | - | - | Not tested | ||

| Gupta et al. (2000) [45] | AD | 4 | ≤0.03 b | NA | NA | ≤0.03 |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Peano, A.; Pasquetti, M.; Tizzani, P.; Chiavassa, E.; Guillot, J.; Johnson, E. Methodological Issues in Antifungal Susceptibility Testing of Malassezia pachydermatis. J. Fungi 2017, 3, 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof3030037

Peano A, Pasquetti M, Tizzani P, Chiavassa E, Guillot J, Johnson E. Methodological Issues in Antifungal Susceptibility Testing of Malassezia pachydermatis. Journal of Fungi. 2017; 3(3):37. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof3030037

Chicago/Turabian StylePeano, Andrea, Mario Pasquetti, Paolo Tizzani, Elisa Chiavassa, Jacques Guillot, and Elizabeth Johnson. 2017. "Methodological Issues in Antifungal Susceptibility Testing of Malassezia pachydermatis" Journal of Fungi 3, no. 3: 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof3030037