Ecoepidemiology of Cryptococcus gattii in Developing Countries

Abstract

:1. Introduction

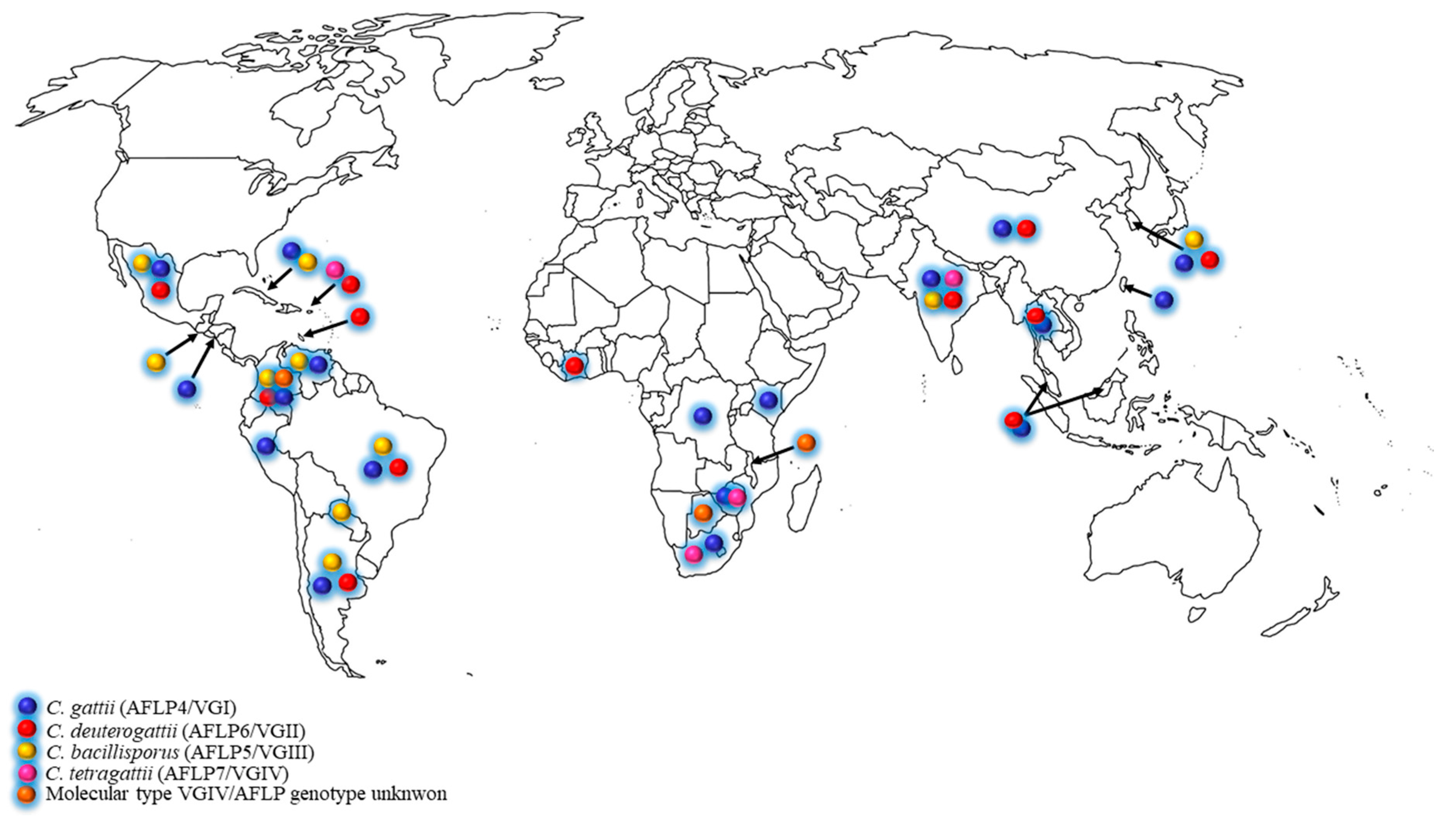

2. Cryptococcus gattii Species Complex Distribution in Developing Countries

2.1. Latin America

2.2. Africa

2.3. Asia

3. Antifungal Susceptibility among the C. gattii Species Complex

4. The C. gattii Species Complex: Four Molecular Types, Five Genotypes or Five Species?

5. Final Remarks

Acknowledgments

Author contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hagen, F.; Khayhan, K.; Theelen, B.; Kolecka, A.; Polacheck, I.; Sionov, E.; Falk, R.; Parnmen, S.; Lumbsch, H.T.; Boekhout, T. Recognition of seven species in the Cryptococcus gattii/Cryptococcus neoformans species complex. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2015, 78, 16–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- May, R.C.; Stone, N.R.H.; Wiesner, D.L.; Bicanic, T.; Nielsen, K. Cryptococcus: From environmental saprophyte to global pathogen. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2015, 14, 106–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajasingham, R.; Smith, R.M.; Park, B.J.; Jarvis, J.N.; Govender, N.P.; Chiller, T.M.; Denning, D.W.; Loyse, A.; Boulware, D.R. Global burden of disease of HIV-associated cryptococcal meningitis: An updated analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2017, 17, 873–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaturvedi, V.; Chaturvedi, S. Cryptococcus gattii: A resurgent fungal pathogen. Trends Microbiol. 2011, 19, 564–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kidd, S.E.; Hagen, F.; Tscharke, R.L.; Huynh, M.; Bartlett, K.H.; Fyfe, M.; MacDougall, L.; Boekhout, T.; Kwon-Chung, K.J.; Meyer, W. A rare genotype of Cryptococcus gattii caused the cryptococcosis outbreak on Vancouver Island (British Columbia, Canada). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 17258–17263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Datta, K.; Bartlett, K.H.; Baer, R.; Byrnes, E.; Galanis, E.; Heitman, J.; Hoang, L.; Leslie, M.J.; MacDougall, L.; Magill, S.S.; et al. Spread of Cryptococcus gattii into Pacific Northwest Region of the United States. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2009, 15, 1185–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cogliati, M.; D’Amicis, R.; Zani, A.; Montagna, M.T.; Caggiano, G.; De Giglio, O.; Balbino, S.; De Donno, A.; Serio, F.; Susever, S.; et al. Environmental distribution of Cryptococcus neoformans and C. gattii around the Mediterranean basin. FEMS Yeast Res. 2016, 16, fow045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khayhan, K.; Hagen, F.; Norkaew, T.; Puengchan, T.; Boekhout, T.; Sriburee, P. Isolation of Cryptococcus gattii from a Castanopsis argyrophylla tree hollow (Mai-Kaw), Chiang Mai, Thailand. Mycopathologia 2017, 182, 365–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vélez, N.; Escandón, P. Report on novel environmental niches for Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii in Colombia: Tabebuia guayacan and Roystonea regia. Med. Mycol. 2017, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon-Chung, K.J.; Bennett, J.E. High prevalence of Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii in tropical and subtropical regions. Zentralbl. Bakteriol. Mikrobiol. Hyg. A 1984, 257, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Galanis, E.; MacDougall, L.; Kidd, S.; Morshed, M.; The British Columbia Cryptococcus gattii working group. Epidemiology of Cryptococcus gattii, British Columbia, Canada, 1999–2007. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2010, 16, 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagen, F.; Boekhout, T. The search for the natural habitat of Cryptococcus gattii. Mycopathologia 2010, 170, 209–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chowdhary, A.; Randhawa, H.S.; Boekhout, T.; Hagen, F.; Klaassen, C.H.; Meis, J.F. Temperate climate niche for Cryptococcus gattii in Northern Europe. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2012, 18, 172–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Colom, M.F.; Hagen, F.; Gonzalez, A.; Mellado, A.; Morera, N.; Linares, C.; García, D.F.; Peñataro, J.S.; Boekhout, T.; Sánchez, M. Ceratonia siliqua (carob) trees as natural habitat and source of infection by Cryptococcus gattii in the Mediterranean environment. Med. Mycol. 2012, 50, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenberg, J.F.; Haulena, M.; Hoang, L.M.N.; Morshed, M.; Zabek, E.; Raverty, S.A. Cryptococcus gattii type VGIIa infection in harbor seals (Phoca vitulina) in British Columbia, Canada. J. Wildl. Dis. 2016, 52, 677–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kidd, S.E.; Chow, Y.; Mak, S.; Bach, P.J.; Chen, H.; Hingston, A.O.; Kronstad, J.W.; Bartlett, K.H. Characterization of environmental sources of the human and animal pathogen Cryptococcus gattii in British Columbia, Canada, and the Pacific Northwest of the United States. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 73, 1433–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagen, F.; Chowdhary, A.; Prakash, A.; Yntema, J.-B.; Meis, J.F. Molecular characterization of Cryptococcus gattii genotype AFLP6/VGII isolated from woody debris of divi-divi (Caesalpinia coriaria), Bonaire, Dutch Caribbean. Rev. Iberoam. Micol. 2014, 31, 193–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anzai, M.C.; dos Santos Lazéra, M.; Wanke, B.; Trilles, L.; Dutra, V.; de Paula, D.A.J.; Nakazato, L.; Takahara, D.T.; Simi, W.B.; Hahn, R.C. Cryptococcus gattii VGII in a Plathymenia reticulata hollow in Cuiabá, Mato Grosso, Brazil. Mycoses 2014, 57, 414–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linares, C.; Colom, M.F.; Torreblanca, M.; Esteban, V.; Romera, Á.; Hagen, F. Environmental sampling of Ceratonia siliqua (carob) trees in Spain reveals the presence of the rare Cryptococcus gattii genotype AFLP7/VGIV. Rev. Iberoam. Micol. 2015, 32, 269–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chowdhary, A.; Randhawa, H.S.; Prakash, A.; Meis, J.F. Environmental prevalence of Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii in India: An update. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2012, 38, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cicora, F.; Petroni, J.; Formosa, P.; Roberti, J. A rare case of Cryptococcus gattii pneumonia in a renal transplant patient. Transpl. Infect. Dis. 2015, 17, 463–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Refojo, N.; Perrotta, D.; Brudny, M.; Abrantes, R.; Hevia, A.I.; Davel, G. Isolation of Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii from trunk hollows of living trees in Buenos Aires City, Argentina. Med. Mycol. 2009, 47, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazza, M.; Refojo, N.; Bosco-Borgeat, M.E.; Taverna, C.G.; Trovero, A.C.; Rogé, A.; Davel, G. Cryptococcus gattii in urban trees from cities in North-eastern Argentina. Mycoses 2013, 56, 646–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cattana, M.E.; de los Ángeles Sosa, M.; Fernández, M.; Rojas, F.; Mangiaterra, M.; Giusiano, G. Native trees of the Northeast Argentine: Natural hosts of the Cryptococcus neoformans-Cryptococcus gattii species complex. Rev. Iberoam. Micol. 2014, 31, 188–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trilles, L.; dos Santos Lazéra, M.; Wanke, B.; Oliveira, R.V.; Barbosa, G.G.; Nishikawa, M.M.; Morales, B.P.; Meyer, W. Regional pattern of the molecular types of Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii in Brazil. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2008, 103, 455–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martins, L.M.S.; Wanke, B.; dos Santos Lazéra, M.; Trilles, L.; Barbosa, G.G.; de Macedo, R.C.L.; do Amparo Salmito Cavalcanti, M.; Eulálio, K.D.; Castro, J.A.; Silva, A.S.; et al. Genotypes of Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii as agents of endemic cryptococcosis in Teresina, Piauí (northeastern Brazil). Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2011, 106, 725–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nascimento, E.; Bonifácio da Silva, M.E.N.; Martinez, R.; von Zeska Kress, M.R. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis in an immunocompetent patient due to Cryptococcus gattii molecular type VGI in Brazil: A case report and review of literature. Mycoses 2014, 57, 442–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abegg, M.A.; Cella, F.L.; Faganello, J.; Valente, P.; Schrank, A.; Vainstein, M.H. Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii isolated from the excreta of Psittaciformes in a Southern Brazilian Zoological Garden. Mycopathologia 2006, 161, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lizarazo, J.; Escandón, P.; Agudelo, C.I.; Firacative, C.; Meyer, W.; Castañeda, E. Retrospective study of the epidemiology and clinical manifestations of Cryptococcus gattii infections in Colombia from 1997–2011. PLoS Neglect. Trop. Dis. 2014, 8, e3272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Escandón, P.; Castañeda, E. Long-term survival of Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii in stored environmental samples from Colombia. Rev. Iberoam. Micol. 2015, 32, 197–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Illnait-Zaragozí, M.T.; Hagen, F.; Fernández-Andreu, C.M.; Martínez-Machín, G.F.; Polo-Leal, J.L.; Boekhout, T.; Klaassen, C.H.; Meis, J.F. Reactivation of a Cryptococcus gattii infection in a cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus) held in the National Zoo, Havana, Cuba. Mycoses 2011, 54, e889–e892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boekhout, T.; Theelen, B.; Diaz, M.; Fell, J.W.; Hop, W.C.; Abeln, E.C.; Dromer, F.; Meyer, W. Hybrid genotypes in the pathogenic yeast Cryptococcus neoformans. Microbiology 2001, 147, 891–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olivares, L.R.C.; Martínez, K.M.; Cruz, R.M.B.; Rivera, M.A.M.; Meyer, W.; Espinosa, R.A.A.; Martínez, R.L.; Santos, G.M.R.P.Y. Genotyping of Mexican Cryptococcus neoformans and C. gattii isolates by PCR-fingerprinting. Med. Mycol. 2009, 47, 713–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González, G.M.; Casillas-Vega, N.; Garza-González, E.; Hernández-Bello, R.; Rivera, G.; Rodríguez, J.A.; Bocanegra-Garcia, V. Molecular typing of clinical isolates of Cryptococcus neoformans/Cryptococcus gattii species complex from Northeast Mexico. Folia Microbiol. 2016, 61, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, W.; Castañeda, A.; Jackson, S.; Huynh, M.; Castañeda, E.; the IberoAmerican cryptococcal study group. Molecular typing of IberoAmerican Cryptococcus neoformans isolates. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2003, 9, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freire, A.K.L.; dos Santos Bentes, A.; de Lima Sampaio, I.; Matsuura, A.B.J.; Ogusku, M.M.; Salem, J.I.; Wanke, B.; de Souza, J.V.B. Molecular characterisation of the causative agents of cryptococcosis in patients of a tertiary healthcare facility in the state of Amazonas-Brazil: Cryptococcosis in the state of Amazonas-Brazil. Mycoses 2012, 55, e145–e150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matos, C.S.; de Souza Andrade, A.; Oliveira, N.S.; Barros, T.F. Microbiological characteristics of clinical isolates of Cryptococcus spp. in Bahia, Brazil: Molecular types and antifungal susceptibilities. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2012, 31, 1647–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herkert, P.F.; Hagen, F.; de Oliveira Salvador, G.L.; Gomes, R.R.; Ferreira, M.S.; Vicente, V.A.; Muro, M.D.; Pinheiro, R.L.; Meis, J.F.; Queiroz-Telles, F. Molecular characterisation and antifungal susceptibility of clinical Cryptococcus deuterogattii (AFLP6/VGII) isolates from Southern Brazil. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2016, 35, 1803–1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Headley, S.A.; Di Santis, G.W.; de Alcântara, B.K.; Costa, T.C.; da Silva, E.O.; Pretto-Giordano, L.G.; Gomes, L.A.; Alfieri, A.A.; Bracarense, A.P.F.R.L. Cryptococcus gattii-induced infections in dogs from Southern Brazil. Mycopathologia 2015, 180, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Abreu, D.P.B.; Machado, C.H.; Makita, M.T.; Botelho, C.F.M.; Oliveira, F.G.; da Veiga, C.C.P.; dos Anjos Martins, M.; de Assis Baroni, F. Intestinal lesion in a dog due to Cryptococcus gattii type VGII and review of published cases of canine gastrointestinal cryptococcosis. Mycopathologia 2016, 182, 597–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, S.P.; Lazéra, M.; Santos, W.R.; Morales, B.P.; Bezerra, C.C.; Nishikawa, M.M.; Barbosa, G.G.; Trilles, L.; Nascimento, J.L.; Wanke, B. First isolation of Cryptococcus gattii molecular type VGII and Cryptococcus neoformans molecular type VNI from environmental sources in the city of Belém, Pará, Brazil. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2009, 104, 662–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, G.S.B.; Freire, A.K.L.; dos Santos Bentes, A.; de Souza Pinheiro, J.F.; de Souza, J.V.B.; Wanke, B.; Matsuura, T.; Jackisch-Matsuura, A.B. Molecular typing of environmental Cryptococcus neoformans/C. gattii species complex isolates from Manaus, Amazonas, Brazil. Mycoses 2016, 59, 509–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fortes, S.T.; Lazera, M.S.; Nishikawa, M.M.; Macedo, R.C.; Wanke, B. First isolation of Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii from a native jungle tree in the Brazilian Amazon rainforest. Mycoses 2001, 44, 137–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brito-Santos, F.; Barbosa, G.G.; Trilles, L.; Nishikawa, M.M.; Wanke, B.; Meyer, W.; Carvalho-Costa, F.A.; dos Santos Lazéra, M. Environmental isolation of Cryptococcus gattii VGII from indoor dust from typical wooden houses in the deep Amazonas of the Rio Negro basin. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0115866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Debourgogne, A.; Hagen, F.; Elenga, N.; Long, L.; Blanchet, D.; Veron, V.; Lortholary, O.; Carme, B.; Aznar, C. Successful treatment of Cryptococcus gattii neurocryptococcosis in a 5-year-old immunocompetent child from the French Guiana Amazon region. Rev. Iberoam. Micol. 2012, 29, 210–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loperena-Alvarez, Y.; Ren, P.; Li, X.; Bopp, D.J.; Ruiz, A.; Chaturvedi, V.; Rios-Velazquez, C. Genotypic characterization of environmental isolates of Cryptococcus gattii from Puerto Rico. Mycopathologia 2010, 170, 279–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Escandón, P.; Sánchez, A.; Firacative, C.; Castañeda, E. Isolation of Cryptococcus gattii molecular type VGIII, from Corymbia ficifolia detritus in Colombia. Med. Mycol. 2010, 48, 675–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Firacative, C.; Roe, C.C.; Malik, R.; Ferreira-Paim, K.; Escandón, P.; Sykes, J.E.; Castañón-Olivares, L.R.; Contreras-Peres, C.; Samayoa, B.; Sorrell, T.C.; et al. MLST and Whole-Genome-Based population analysis of Cryptococcus gattii VGIII links clinical, veterinary and environmental strains, and reveals divergent serotype specific sub-populations and distant ancestors. PLoS Neglect. Trop. Dis. 2016, 10, e0004861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steele, K.T.; Thakur, R.; Nthobatsang, R.; Steenhoff, A.P.; Bisson, G.P. In-hospital mortality of HIV-infected cryptococcal meningitis patients with C. gattii and C. neoformans infection in Gaborone, Botswana. Med. Mycol. 2010, 48, 1112–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogaerts, J.; Rouvroy, D.; Taelman, H.; Kagame, A.; Aziz, M.A.; Swinne, D.; Verhaegen, J. AIDS-associated cryptococcal meningitis in Rwanda (1983–1992): Epidemiologic and diagnostic features. J. Infect. 1999, 39, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karstaedt, A.S.; Crewe-Brown, H.H.; Dromer, F. Cryptococcal meningitis caused by Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii, serotype C, in AIDS patients in Soweto, South Africa. Med. Mycol. 2002, 40, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, J.; McCarthy, K.M.; Gould, S.; Fan, K.; Arthington-Skaggs, B.; Iqbal, N.; Stamey, K.; Hajjeh, R.A.; Brandt, M.E. Cryptococcus gattii infection: Characteristics and epidemiology of cases identified in a South African province with high HIV seroprevalence, 2002–2004. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2006, 43, 1077–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meiring, S.T.; Quan, V.C.; Cohen, C.; Dawood, H.; Karstaedt, A.S.; McCarthy, K.M.; Whitelaw, A.C.; Govender, N.P.; Group for Enteric; Respiratory and Meningeal disease Surveillance in South Africa (GERMS-SA). A comparison of cases of paediatric-onset and adult-onset cryptococcosis detected through population-based surveillance, 2005–2007. AIDS 2012, 26, 2307–2314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanhove, M.; Beale, M.A.; Rhodes, J.; Chanda, D.; Lakhi, S.; Kwenda, G.; Molloy, S.; Karunaharan, N.; Stone, N.; Harrison, T.S.; et al. Genomic epidemiology of Cryptococcus yeasts identifies adaptation to environmental niches underpinning infection across an African HIV/AIDS cohort. Mol. Ecol. 2016, 26, 1991–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kangogo, M.; Bader, O.; Boga, H.; Wanyoike, W.; Folba, C.; Worasilchai, N.; Weig, M.; Groß, U.; Bii, C.C. Molecular types of Cryptococcus gattii/Cryptococcus neoformans species complex from clinical and environmental sources in Nairobi, Kenya. Mycoses 2015, 58, 665–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Wyk, M.; Govender, N.P.; Mitchell, T.G.; Litvintseva, A.P. Multilocus sequence typing of serially collected isolates of Cryptococcus from HIV-infected patients in South Africa. Land GA, ed. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2014, 52, 1921–1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nyazika, T.K.; Hagen, F.; Meis, J.F.; Robertson, V.J. Cryptococcus tetragattii as a major cause of cryptococcal meningitis among HIV-infected individuals in Harare, Zimbabwe. J. Infect. 2016, 72, 745–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nyazika, T.K.; Herkert, P.F.; Hagen, F.; Mateveke, K.; Robertson, V.J.; Meis, J.F. In vitro antifungal susceptibility profiles of Cryptococcus species isolated from HIV-associated cryptococcal meningitis patients in Zimbabwe. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2016, 86, 289–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kassi, F.K.; Drakulovski, P.; Bellet, V.; Krasteva, D.; Gatchitch, F.; Doumbia, A.; Kouakou, G.A.; Delaporte, E.; Reynes, J.; Mallié, M.; et al. Molecular epidemiology reveals genetic diversity among 363 isolates of the Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii species complex in 61 Ivorian HIV-positive patients. Mycoses 2016, 59, 811–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Litvintseva, A.P.; Thakur, R.; Reller, L.B.; Mitchell, T.G. Prevalence of clinical isolates of Cryptococcus gattii serotype C among patients with AIDS in Sub-Saharan Africa. J. Infect. Dis. 2005, 192, 888–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiujiao, X.; Ai’e, X. Two cases of cutaneous cryptococcosis. Mycoses 2005, 48, 238–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capoor, M.R.; Mandal, P.; Deb, M.; Aggarwal, P.; Banerjee, U. Current scenario of cryptococcosis and antifungal susceptibility pattern in India: A cause for reappraisal. Mycoses 2008, 51, 258–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patil, R.T. Meningitis due to Cryptococcus gattii in an immunocompetent patient. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2013, 7, 2274–2275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Randhawa, H.S.; Kowshik, T.; Preeti Sinha, K.; Chowdhary, A.; Khan, Z.U.; Yan, Z.; Xu, J.; Kumar, A. Distribution of Cryptococcus gattii and Cryptococcus neoformans in decayed trunk wood of Syzygium cumini trees in north-western India. Med. Mycol. 2006, 44, 623–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Randhawa, H.S.; Kowshik, T.; Chowdhary, A.; Preeti Sinha, K.; Khan, Z.U.; Sun, S.; Xu, J. The expanding host tree species spectrum of Cryptococcus gattii and Cryptococcus neoformans and their isolations from surrounding soil in India. Med. Mycol. 2008, 46, 823–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, Z.U.; Randhawa, H.S.; Kowshik, T.; Chowdhary, A.; Chandy, R. Antifungal susceptibility of Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii isolates from decayed wood of trunk hollows of Ficus religiosa and Syzygium cumini trees in north-western India. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2007, 60, 312–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Girish Kumar, C.P.; Prabu, D.; Mitani, H.; Mikami, Y.; Menon, T. Environmental isolation of Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii from living trees in Guindy National Park, Chennai, South India. Mycoses 2010, 53, 262–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutch, R.S.; Nawange, S.R.; Singh, S.M.; Yadu, R.; Tiwari, A.; Gumasta, R.; Kavishwar, A. Antifungal susceptibility of clinical and environmental Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii isolates in Jabalpur, a city of Madhya Pradesh in Central India. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2015, 46, 1125–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bedi, N.G.; Nawange, S.R.; Singh, S.M.; Naidu, J.; Kavishwar, A. Seasonal prevalence of Cryptococcus neoformans var. grubii and Cryptococcus gattii inhabiting Eucalyptus terreticornis and Eucalyptus camaldulensis trees in Jabalpur City of Madhya Pradesh, Central India. J. Med. Mycol. 2012, 22, 341–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.C.; Chang, S.C.; Shih, C.C.; Hung, C.C.; Luhbd, K.T.; Pan, Y.S.; Hsieh, W.C. Clinical features and in vitro susceptibilities of two varieties of Cryptococcus neoformans in Taiwan. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2000, 36, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lui, G. Cryptococcosis in apparently immunocompetent patients. QJM 2006, 99, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Varma, A.; Diaz, M.R.; Litvintseva, A.P.; Wollenberg, K.K.; Kwon-Chung, K.J. Cryptococcus neoformans strains and infection in apparently immunocompetent patients, China. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2008, 14, 755–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, X.; Yao, Z.; Ren, D.; Liao, W.; Wu, J. Genotype and mating type analysis of Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii isolates from China that mainly originated from non-HIV-infected patients. FEMS Yeast Res. 2008, 8, 930–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dou, H.-T.; Xu, Y.-C.; Wang, H.-Z.; Li, T.-S. Molecular epidemiology of Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii in China between 2007 and 2013 using multilocus sequence typing and the DiversiLab system. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2015, 34, 753–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, S.-Y.; Lei, Y.; Kang, M.; Xiao, Y.-L.; Chen, Z.-X. Molecular characterisation of clinical Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii isolates from Sichuan province, China. Mycoses 2015, 58, 280–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lahiri Mukhopadhyay, S.; Bahubali, V.H.; Manjunath, N.; Swaminathan, A.; Maji, S.; Palaniappan, M.; Parthasarathy, S.; Chandrashekar, N. Central nervous system infection due to Cryptococcus gattii sensu lato in India: Analysis of clinical features, molecular profile and antifungal susceptibility. Mycoses 2017, 60, 749–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Randhawa, H.S.; Kowshik, T.; Chowdhary, A.; Prakash, A.; Khan, Z.U.; Xu, J. Seasonal variations in the prevalence of Cryptococcus neoformans var. grubii and Cryptococcus gattii in decayed wood inside trunk hollows of diverse tree species in north-western India: A retrospective study. Med. Mycol. 2011, 49, 320–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chowdhary, A.; Prakash, A.; Randhawa, H.S.; Kathuria, S.; Hagen, F.; Klaassen, C.H.; Meis, J.F. First environmental isolation of Cryptococcus gattii, genotype AFLP5, from India and a global review: Cryptococcus gattii, genotype AFLP5, from India. Mycoses 2013, 56, 222–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.H.; Choi, S.C.; Lee, K.W.; Kim, M.-N.; Hwang, S.M. Genotypes of clinical and environmental isolates of Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii in Korea. Mycobiology 2015, 43, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tay, S.T.; Lim, H.C.; Tajuddin, T.H.; Rohani, M.Y.; Hamimah, H.; Thong, K.L. Determination of molecular types and genetic heterogeneity of Cryptococcus neoformans and C. gattii in Malaysia. Med. Mycol. 2006, 44, 617–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tay, S.T.; Rohani, M.Y.; Soo Hoo, T.S.; Hamimah, H. Epidemiology of cryptococcosis in Malaysia: Epidemiology of Cryptococcus neoformans. Mycoses 2010, 53, 509–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liaw, S.-J.; Wu, H.-C.; Hsueh, P.-R. Microbiological characteristics of clinical isolates of Cryptococcus neoformans in Taiwan: Serotypes, mating types, molecular types, virulence factors, and antifungal susceptibility. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2010, 16, 696–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaocharoen, S.; Ngamskulrungroj, P.; Firacative, C.; Trilles, L.; Piyabongkarn, D.; Banlunara, W.; Poonwan, N.; Chaiprasert, A.; Meyer, W.; Chindamporn, A. Molecular epidemiology reveals genetic diversity amongst isolates of the Cryptococcus neoformans/C. gattii species complex in Thailand. PLoS Neglect. Trop. Dis. 2013, 7, e2297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, N.; Wickes, B.L.; Keller, S.M.; Fu, J.; Casadevall, A.; Jain, P.; Ragan, M.A.; Banerjee, U.; Fries, B.C. Molecular epidemiology of clinical Cryptococcus neoformans strains from India. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2005, 43, 5733–5742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Choi, Y.H.; Ngamskulrungroj, P.; Varma, A.; Sionov, E.; Hwang, S.M.; Carriconde, F.; Meyer, W.; Litvintseva, A.P.; Lee, W.G.; Shin, J.H.; et al. Prevalence of the VNIc genotype of Cryptococcus neoformans in non-HIV-associated cryptococcosis in the Republic of Korea: Molecular epidemiology of cryptococcosis in Korea. FEMS Yeast Res. 2010, 10, 769–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leechawengwongs, M.; Milindankura, S.; Sathirapongsasuti, K.; Tangkoskul, T.; Punyagupta, S. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis caused by Cryptococcus gattii VGII in a tsunami survivor from Thailand. Med. Mycol. Case Rep. 2014, 6, 31–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cogliati, M.; Chandrashekar, N.; Esposto, M.C.; Chandramuki, A.; Petrini, B.; Viviani, M.A. Cryptococcus gattii serotype-C strains isolated in Bangalore, Karnataka, India: Cryptococcus gattii in Bangalore. Mycoses 2012, 55, 262–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Illnait-Zaragozí, M.T.; Ortega-Gonzalez, L.M.; Hagen, F.; Martínez-Machin, G.F.; Meis, J.F. Fatal Cryptococcus gattii genotype AFLP5 infection in an immunocompetent Cuban patient. Med. Mycol. Case Rep. 2013, 2, 48–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casadevall, A.; Freij, J.B.; Hann-Soden, C.; Taylor, J. Continental drift and speciation of the Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii species complexes. mSphere 2017, 2, e00103-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engelthaler, D.M.; Meyer, W. Furthering the continental drift speciation hypothesis in the pathogenic Cryptococcus species complexes. mSphere 2017, 2, e00241-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espinel-Ingroff, A.; Aller, A.I.; Canton, E.; Castanon-Olivares, L.R.; Chowdhary, A.; Cordoba, S.; Cuenca-Estrella, M.; Fothergill, A.; Fuller, J.; Govender, N.; et al. Cryptococcus neoformans-Cryptococcus gattii species complex: An international study of wild-type susceptibility endpoint distributions and epidemiological cutoff values for fluconazole, itraconazole, posaconazole, and voriconazole. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012, 56, 5898–5906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espinel-Ingroff, A.; Chowdhary, A.; Gonzalez, G.M.; Guinea, J.; Hagen, F.; Meis, J.F.; Thompson, G.R.; Turnidge, J. Multicenter study of isavuconazole MIC distributions and epidemiological cutoff values for the Cryptococcus neoformans-Cryptococcus gattii species complex using the CLSI M27-A3 broth microdilution method. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015, 59, 666–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Trilles, L.; Meyer, W.; Wanke, B.; Guarro, J.; Lazéra, M. Correlation of antifungal susceptibility and molecular type within the Cryptococcus neoformans/C. gattii species complex. Med. Mycol. 2012, 50, 328–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Favalessa, O.C.; De Paula, D.A.J.; Dutra, V.; Nakazato, L.; Tadano, T.; dos Santos Lazera, M.; Wanke, B.; Trilles, L.; Walderez Szeszs, M.; Silva, D.; et al. Molecular typing and in vitro antifungal susceptibility of Cryptococcus spp from patients in Midwest Brazil. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2014, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagen, F.; Illnait-Zaragozi, M.-T.; Bartlett, K.H.; Swinne, D.; Geertsen, E.; Klaassen, C.H.W.; Boekhout, T.; Meis, J.F. In vitro antifungal susceptibilities and amplified fragment length polymorphism genotyping of a worldwide collection of 350 clinical, veterinary, and environmental Cryptococcus gattii isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2010, 54, 5139–5145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lockhart, S.R.; Iqbal, N.; Bolden, C.B.; DeBess, E.E.; Marsden-Haug, N.; Worhle, R.; Thakur, R.; Harris, J.R. Epidemiologic cutoff values for triazole drugs in Cryptococcus gattii: Correlation of molecular type and in vitro susceptibility. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2012, 73, 144–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perfect, J.R.; Dismukes, W.E.; Dromer, F.; Goldman, D.L.; Graybill, J.R.; Hamill, R.J.; Harrison, T.S.; Larsen, R.A.; Lortholary, O.; Nguyen, M.; et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of cryptococcal disease: 2010 update by the infectious diseases society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2010, 50, 291–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varma, A.; Kwon-Chung, K.J. Heteroresistance of Cryptococcus gattii to Fluconazole. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2010, 54, 2303–2311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, G.F.; Santos, J.R.A.; da Costa, M.C.; de Holanda, R.A.; Denadai, Â.M.L.; de Freitas, G.J.C.; Santos, Á.R.C.; Tavares, P.B.; Paixão, T.A.; Santos, D.A. Heteroresistance to itraconazole alters the morphology and increases the virulence of Cryptococcus gattii. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015, 59, 4600–4609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sionov, E.; Chang, Y.C.; Garraffo, H.M.; Kwon-Chung, K.J. Heteroresistance to fluconazole in Cryptococcus neoformans is intrinsic and associated with virulence. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2009, 53, 2804–2815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falagas, M.E.; Makris, G.C.; Dimopoulos, G.; Matthaiou, D.K. Heteroresistance: A concern of increasing clinical significance? Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2008, 14, 101–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.-Z.; Wang, Q.-M.; Göker, M.; Groenewald, M.; Kachalkin, A.V.; Lumbsch, H.T.; Millanes, A.M.; Wedin, M.; Yurkov, A.M.; Boekhout, T.; et al. Towards an integrated phylogenetic classification of the Tremellomycetes. Stud. Mycol. 2015, 81, 85–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.-Z.; Wang, Q.-M.; Theelen, B.; Groenewald, M.; Bai, F.-Y.; Boekhout, T. Phylogeny of tremellomycetous yeasts and related dimorphic and filamentous basidiomycetes reconstructed from multiple gene sequence analyses. Stud. Mycol. 2015, 81, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coenjaerts, F.E.J. The sixth international conference on Cryptococcus and cryptococcosis: The sixth international conference on Cryptococcus and cryptococcosis (ICCC). FEMS Yeast Res. 2006, 6, 312–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon-Chung, J. Is it a one, two, or more species system supported by the major species concept? In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Cryptococcus and Cryptococcosis, Boston, MA, USA, 24–28 June 2005; p. 43. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon-Chung, K.J.; Varma, A. Do major species concepts support one, two or more species within Cryptococcus neoformans? FEMS Yeast Res. 2006, 6, 574–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boekhout, T.; Bovers, M.; Fell, J.W.; Diaz, M.; Hagen, F.; Theelen, B.; Kuramae, E. How many species? In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Cryptococcus and Cryptococcosis, Boston, MA, USA, 24–28 June 2005; p. 44. [Google Scholar]

- Bovers, M.; Hagen, F.; Kuramae, E.E.; Boekhout, T. Six monophyletic lineages identified within Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii by multi-locus sequence typing. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2008, 45, 400–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, W.; Boekhout, T.; Castañeda, E.; Karaoglu, H.; Ngamskulrungroj, P.; Kidd, S.; Escandón, P.; Hagen, F.; Narszewska, K.; Velegraki, A. Molecular characterization of the Cryptococcus neoformans species complex. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Cryptococcus and Cryptococcosis, Boston, MA, USA, 24–28 June 2005; pp. 41–42. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon-Chung, K.J.; Bennett, J.E.; Wickes, B.L.; Meyer, W.; Cuomo, C.A.; Wollenburg, K.R.; Bicanic, T.A.; Castañeda, E.; Chang, Y.C.; Chen, J.; et al. The case for adopting the “species complex” nomenclature for the etiologic agents of cryptococcosis. mSphere 2017, 2, e00357-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, K.E.; Dwyer, C.; Campbell, L.T.; Carter, D.A. Species in the Cryptococcus gattii complex differ in capsule and cell size following growth under capsule-inducing conditions. mSphere 2016, 1, e00350-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, G.R.; Albert, N.; Hodge, G.; Wilson, M.D.; Sykes, J.E.; Bays, D.J.; Firacative, C.; Meyer, W.; Kontoyiannis, D.P. Phenotypic differences of Cryptococcus molecular types and their implications for virulence in a Drosophila model of infection. Infect. Immun. 2014, 82, 3058–3065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, J.W.; Jacobson, D.J.; Kroken, S.; Kasuga, T.; Geiser, D.M.; Hibbett, D.S.; Fisher, M.C. Phylogenetic species recognition and species concepts in fungi. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2000, 31, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Souza, C.A.; Kronstad, J.W.; Taylor, G.; Warren, R.; Yuen, M.; Hu, G.; Jung, W.H.; Sham, A.; Kidd, S.E.; Tangen, K.; et al. Genome variation in Cryptococcus gattii, an emerging pathogen of immunocompetent hosts. MBio 2011, 2, e00342-10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngamskulrungroj, P.; Gilgado, F.; Faganello, J.; Litvintseva, A.P.; Leal, A.L.; Tsui, K.M.; Mitchell, T.G.; Vainstein, M.H.; Meyer, W. Genetic diversity of the Cryptococcus species complex suggests that Cryptococcus gattii deserves to have varieties. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e5862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallet, J. Hybridization as an invasion of the genome. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2005, 20, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagen, F.; Lumbsch, H.T.; Arsic Arsenijevic, V.; Badali, H.; Bertout, S.; Billmyre, R.B.; Bragulat, M.R.; Cabañes, F.J.; Carbia, M.; Chakrabarti, A.; et al. Importance of resolving fungal nomenclature: The case of multiple pathogenic species in the Cryptococcus Genus. mSphere 2017, 2, e00238-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Continent | Species | Source | Country |

|---|---|---|---|

| Latin America | C. gattii s.s. | Clinical, Environmental, Veterinary | Argentina [21,22,23,24], Brazil [25,26,27,28], Colombia [29,30], Cuba [31], Honduras [32], Mexico [33,34], Peru [35] |

| C. deuterogattii | Clinical, Environmental, Veterinary | Brazil [18,25,26,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44], Colombia [29,30], French Guiana [45], Mexico [33,34], Puerto Rico [46] | |

| C. bacillisporus | Clinical, Environmental | Argentina [23], Brazil [25], Colombia [29,30,47], Cuba [48], Guatemala [48], Mexico [33,34], Paraguay [48], Venezuela [48] | |

| C. tetragattii | Environmental | Colombia [35], Mexico [33,34], Puerto Rico [46] | |

| Africa | C. gattii s.l. | Clinical, Environmental | Botswana [49], Rwanda [50], South Africa [51,52,53], Zambia [54] |

| C. gattii s.s. | Clinical | D.R. Congo [32], Kenya [55], South Africa [56], Zimbabwe [57,58] | |

| C. deuterogattii | Clinical | Ivory Coast [59] | |

| C. tetragattii | Clinical, Veterinary | Botswana [60], Malawi [60], South Africa [57]; Zimbabwe [57,58] | |

| Asia | C. gattii s.l. | Clinical, Environmental | China [61,62,63], India [64,65,66,67,68,69], Taiwan [70] |

| C. gattii s.s. | Clinical, Environmental | China [71,72,73,74,75], India [76,77,78], Korea [79], Malaysia [80,81], Taiwan [82], Thailand [8,83] | |

| C. deuterogattii | Clinical | China [71,74,75], India [84], Korea [79,85], Malaysia [80,81], Thailand [83,86] | |

| C. bacillisporus | Clinical, Environmental | India [78], Korea [79,85] | |

| C. tetragattii | Clinical, Veterinary | India [87] |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Herkert, P.F.; Hagen, F.; Pinheiro, R.L.; Muro, M.D.; Meis, J.F.; Queiroz-Telles, F. Ecoepidemiology of Cryptococcus gattii in Developing Countries. J. Fungi 2017, 3, 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof3040062

Herkert PF, Hagen F, Pinheiro RL, Muro MD, Meis JF, Queiroz-Telles F. Ecoepidemiology of Cryptococcus gattii in Developing Countries. Journal of Fungi. 2017; 3(4):62. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof3040062

Chicago/Turabian StyleHerkert, Patricia F., Ferry Hagen, Rosangela L. Pinheiro, Marisol D. Muro, Jacques F. Meis, and Flávio Queiroz-Telles. 2017. "Ecoepidemiology of Cryptococcus gattii in Developing Countries" Journal of Fungi 3, no. 4: 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof3040062