1. Introduction

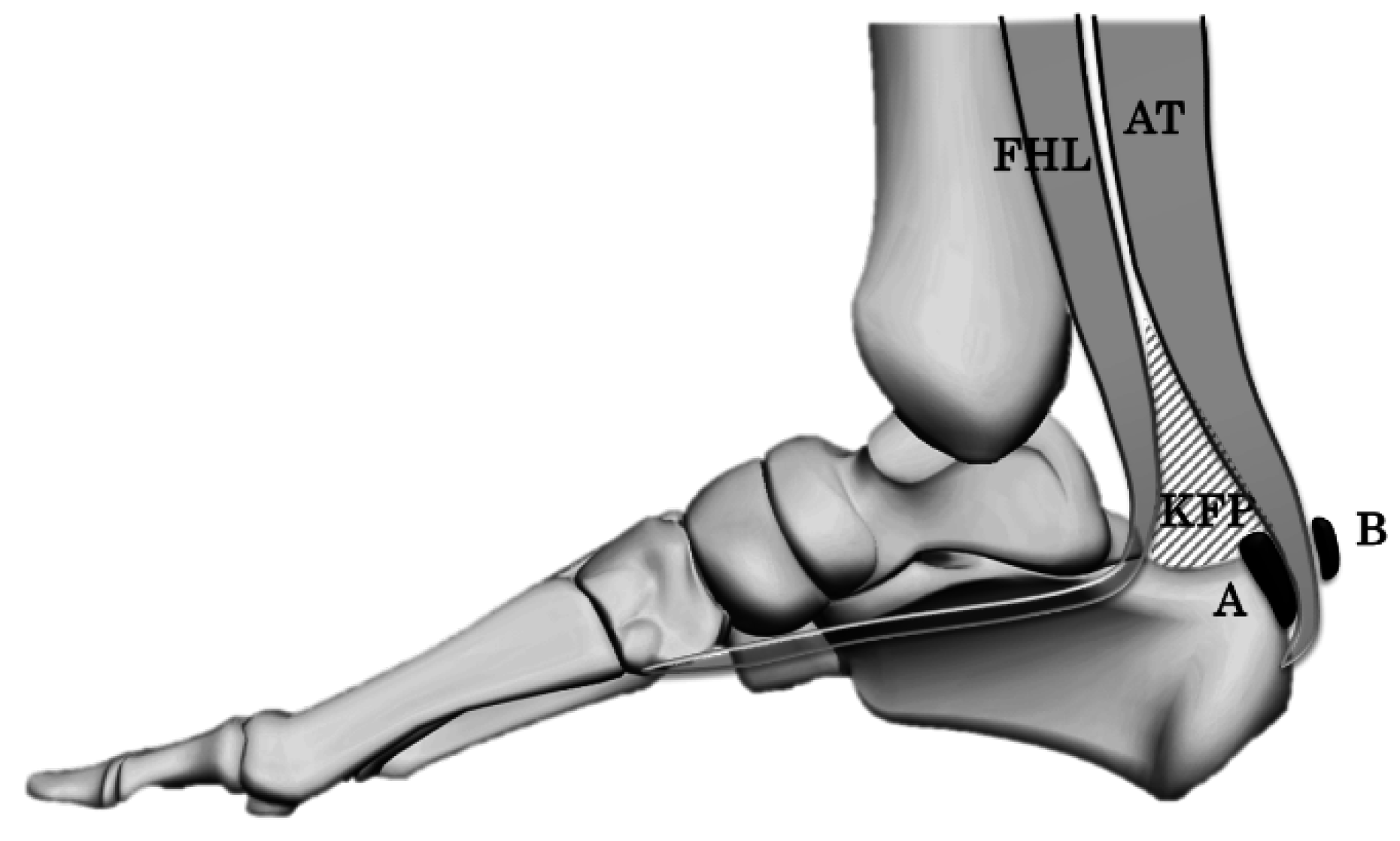

Achilles tendon bursitis is a common cause of heel pain. The Achilles tendon bursa consists of a subcutaneous and retrocalcaneal bursa (RB) (

Figure 1). The RB is located between Kager’s fat pad (KFP) and the Achilles tendon, and it moves with the KFP during ankle motion (plantar flexion and dorsiflexion) [

1].

RB has three functions: it acts as a shock absorber and a lubricator and removes debris from the posterior side of the Achilles tendon [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6].

On the sagittal plane, the RB is compressed by ankle dorsiflexion, leading to impingement between the calcaneal tuberosity and the Achilles tendon [

2,

3]. Flexor hallucis longus (FHL) contraction facilitates the invagination of the KFP to the RB [

2]. This type of compressive force is thought to be a cause of bursitis [

2]. However, in the horizontal plane, the kinetics of the RB and the influence of FHL contraction are not well examined. The purpose of this study was to assess the shape (thickness) of the RB in the horizontal plane with respect to ankle position with or without FHL contraction. Our hypothesis was that the thickness of the RB in the horizontal plane changes with respect to the ankle position with or without FHL contraction.

2. Materials and Methods

Forty feet of 20 healthy female volunteers (mean, 24.3 years; SD, 4.3 years) with the occupation of physiotherapist were examined (mean, BMI 20.3; SD, 1.5). None of the subjects had a history of significant injury around the ankle.

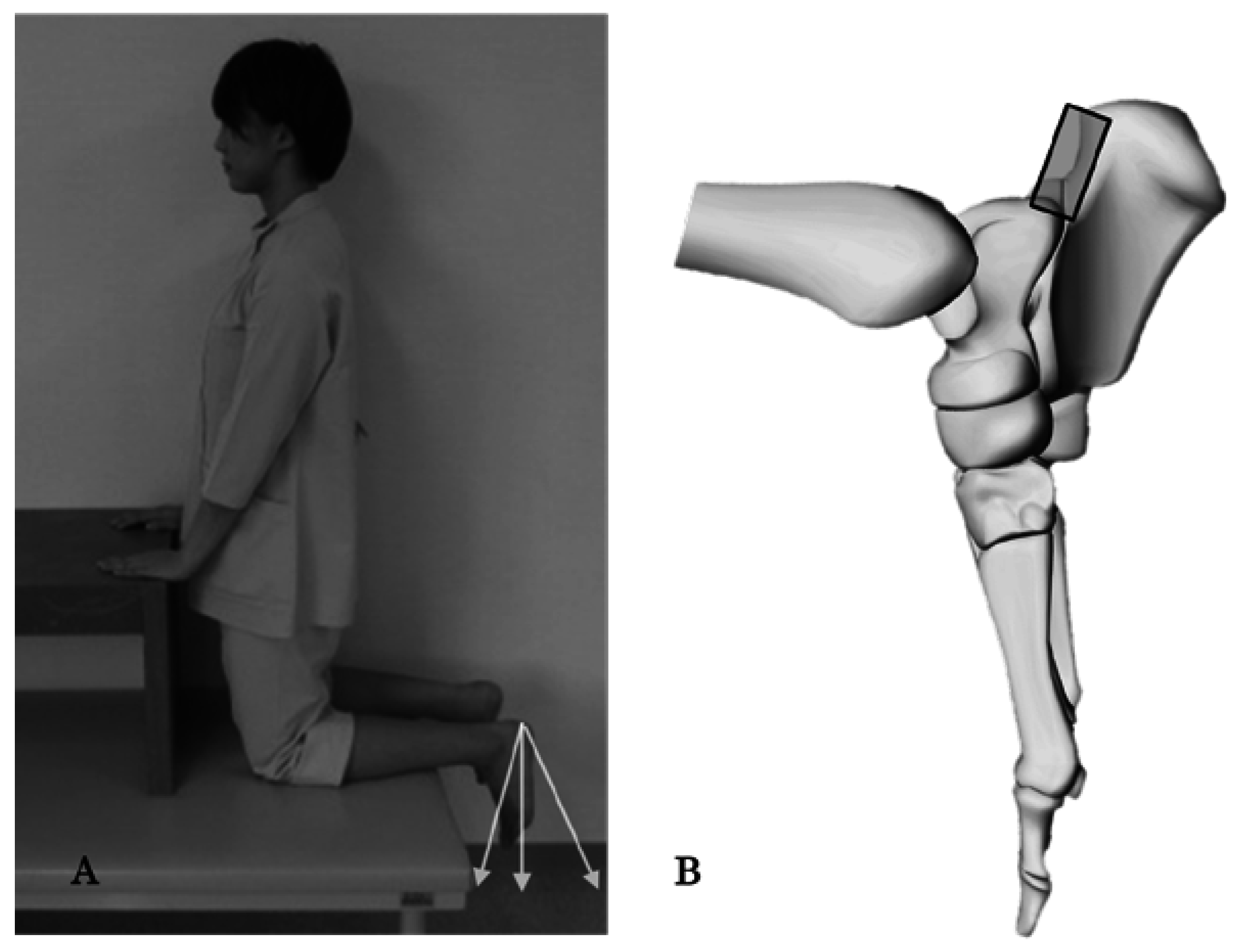

The thickness of RB was measured using an ultrasound imaging system (Prosound α-7, Hitachi, Japan) in three ankle positions (20° dorsiflexion, neutral, and 40° plantar flexion) with or without FHL contraction; all subjects were kneeling (90° hip flexion, 90° knee flexion) to relax the gastrocnemius (

Figure 2). A 14 MHz linear array probe was used to measure the thickness of RB. The thickness of RB in the horizontal plane was defined as the distance between the posteromedial talar process and the calcaneal tuberosity (

Figure 3). Before the study, the reliability of RB thickness measurement was calculated using the intraclass correlation coefficient, which ranged from 0.82 to 0.95 in each condition (ankle position and FHL contraction). The data were analyzed using the non-repeating two-way factorial analysis of variance and Tukey’s method for the post-hoc test.

p ≤ 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

3. Results

Without FHL contraction, the mean thickness of the RB was 2.6 mm in dorsiflexion, 2.4 mm in neutral, and 2.3 mm in plantar flexion (

Table 1). With FHL contraction, the mean thickness of the RB was 2.5 mm in dorsiflexion, 2.5 mm in neutral, and 2.3 mm in plantar flexion. No significant differences were detected with respect to either ankle position or FHL contraction.

4. Discussion

In healthy subjects, the thickness of the RB in the horizontal plane did not change significantly with respect to the ankle position with or without FHL contraction. These results could be interpreted as the subtle change in the horizontal thickness of the RB being related to a pathological condition in the Kager triangle and it could be measured with the ultrasound easily, accurately and dynamically.

In the Kager triangle, the RB moves with KFP [

2,

7]. The KFP consist of three parts: a superficial Achilles tendon–associated part, a deep FHL-associated part, and distal calcaneal bursal wedge [

2]. On the sagittal plane, during ankle plantar flexion, the calcaneal wedge pushes into the RB [

2], and the angle between the Achilles tendon and the calcaneus widens [

2]. FHL contraction facilitates the invagination of the KFP to the RB; however, our study showed a consistent thickness of the RB during ankle motion in the horizontal plane. In addition to the role of shock absorber, the RB acts as a lubricator and removes debris from the posterior side of the Achilles tendon [

4,

5,

6], and the healthy RB contains highly viscous synovial fluid [

8]. Its viscoelastic properties are thought to neutralize compressive stress and resist deformation or corruption during ankle motion.

There are several limitations of this study. First, the sample size of the subjects was limited and all the subjects were young females. Second, disparity in the mechanical axis of the lower limb and the influence of gastrocnemius contraction were not evaluated. Last, the stiffness of the RB wall and the pressure of the RB fluid were not measured. Further study is needed.

5. Conclusions

This study showed that in healthy subjects, the thickness of the RB in the horizontal plane did not change with respect to the ankle position with or without FHL contraction.

Author Contributions

Misako Hamada, Minori Ota and Nobuhide Azuma conducted the acquisition of data; Misako Hamada and Kotaro Yamakado were drafting of manuscript and wrote the main paper. All authors discussed the study conception and design, the results and implications at all stages.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Theobald, P.; Bydder, G.; Dent, C.; Nokes, L.; Pugh, N.; Benjamin, M. The functional anatomy of Kager’s fat pad in relation to retrocalcaneal problems and other hindfoot disorders. J. Anat. 2006, 208, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benjamin, M.; Kumai, T.; Milz, S.; Boszczyk, B.M.; Boszczyk, A.A.; Ralphs, J.R. The skeletal attachment of tendons—Tendon ‘entheses’. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. 2002, 133-A, 931–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rufai, A.; Ralphs, J.R.; Benjamin, M. Structure and histopathology of the insertional region of the human Achilles tendon. J. Orthop. Res. 1995, 13, 585–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benjamin, M.; McGonagle, D. The enthesis organ concept and its relevance to the spondyloarthropathies. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2009, 649, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kumai, T.; Takakura, Y.; Rufai, A.; Milz, S.; Benjamin, M. The functional anatomy of the human anterior talofibular ligament in relation to ankle sprains. J. Anat. 2002, 200, 457–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaw, H.M.; Benjamin, M. Structure-function relationships of enthesis in relation to mechanical load and exercise. Scand. J. Mad. Sci. Sports 2007, 17, 303–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johannes, I.; Somford, M.P.; Hoornenborg, D.; van Dijk, C.N. Eponyms of the Kager Triangle. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 2012, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canoso, J.J.; Liu, N.; Traill, M.R. Physiology of the retrocalcaneal bursa. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 1988, 47, 910–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).