1. Introduction

This paper explores the characteristics and consequences of globalization of the local housing market in Barcelona, with special emphasis on the very recent Chinese investments. We discuss changes in the secondary circuit of capital [

1], and the contradictions between local and foreign capital and their dynamics. We also try to analyze the impact of recent Chinese market socialism [

2], and the processes of social differentiation of Chinese people in their residential location in the city. We also try to compare this recent Chinese investment realized by an economic elite with the less recent investment carried out by the Chinese diaspora.

The main hypothesis is that real estate investments are closely related to macroeconomic trends in the global economy, especially those of emerging countries and the People’s Republic of China. Hence, we should compare recent Chinese investments in the Barcelona market with the pioneering Japanese strategy in the 1980s. The second hypothesis is that Chinese society is becoming capitalist through its involvement in some Western countries, and notably in some selected cities, such as Barcelona [

3,

4].

Consequently, our objective is to define the economic strategies of Chinese investment for the local housing market, and social reactions to the creation of the new types of Chinatown [

5]. The first Chinatown originated from the great immigration flow of Chinese people to the Pacific coast of the United States in the second half of 19th Century. As the American lawyer William Lacy Pollard (1879–1963) pointed it out in 1931, the origin of the first American Chinatowns dates from the implementation of some local ordinances in San Francisco and Modesto (California) in the 1880s. These ordinances regulated the location of Chinese laundries. Pollard found a clear connection between the origin of laws that regulated urban zoning and the ethnic segregation of the Chinese population in these Californian cities [

6]. The first Chinatowns outside China originated from the concentration of laundries, which were mainly owned by Chinese migrants, together with other Chinese shops, restaurants, and business, as well as residences. In Europe, the Italian architect Franco Mancuso analyzed the origins of the zoning, and diffused this idea into the urban studies [

7]. The diffusion of Chinatowns all around North American cities has consolidated their more idyllic and less segregationist image. This image may appear today as a touristic resource in many other cities all over the world, and even in some cities located in China [

5].

Europe has a more recent Chinese immigration, which is remarkably different in its characteristics mainly because it is related to certain degree to important economic investments [

8,

9]. Chinatowns used to be more functional than an ethnopolis, probably because traditionally they were tourist attractions in this cities. In Europe, Italy has been the first country with a significant Chinese settlement, followed by other European capitals, mainly Paris [

10]. In Spain, the name of Chinatown was connected to some vice and poor neighbourhoods, where Chinese inhabitants were in fact absent. This is the case of Barcelona or Salamanca, where Chinese immigration and investments are quite recent. This allows their study and their processes, which lead to more interesting and stimulating trends, to be discovered.

First, we analyze the main trends in globalization from a general perspective. Second, we discuss the impact of globalization on local real estate. Third, we analyze the current segmentation of Barcelona’s real estate market. Fourth, we define the main residential strategies of Chinese people and firms in Barcelona. Finally, we present two conclusions about the formation of Barcelona’s Chinatown and the impact of Chinese investments on the local housing market.

2. Methodological Remarks

From a methodological point of view, it is necessary to remark on the difficulties of approaching the Chinese reality in Barcelona through the information provided by the Chinese residents or investors. There has been extremely poor results of fieldwork, and also of the majority of current statistics, at national, regional, or municipal levels. Interviews and even simple questions from non-Chinese people to the Chinese are normally not very fruitful. The excessive use of a simple statistical approach to social complex problems also contributes to the difficulty of producing new and valuable data. It can be said that we have been confronted with two different kinds of silence.

Nevertheless, it has been very important the results of five in deep interviews to some significant people and representative of institutions. From the famous lawyer’s office Roca Junyent, or the firms Century 21 and Barcelona Solutions (both dedicated to assessing Chinese firms in Barcelona), it has been possible to collect a lot of information about the process of Chinese real estate buying, and its criteria and location. The interview with representatives of the Catalan Tax Agency has furnished general data on urban land values that allow affirmation that there is not yet any negative consequence of the Chinese capital investments into the local urban land market. This conclusion has been confirmed with the Government official data on the Spanish municipalities of more than 50,000 inhabitants. Finally, many interviews with the representatives of the Barcelona’s Confucius Institute have given a lot of information about the behavior of the different groups of the local Chinese community.

It has been also very important to analyze the opinion generated of the Barcelona’s Chinese people, in order to determine changes on the public discourses and their social reception. This opinion has been analyzed from the archives of Barcelona’s most important newspaper La Vanguardia, a real Barcelona Times published since 1881, orienting the opinion of the city elites and diffused at a National level. Using the words “Chinese” and “Barcelona” it has been possible to identify thousands of articles between 1986 and 2014. In addition to the quantitative analysis of the total amount of information it has been also possible to do a more detailed study of a sample of the main articles published in the last 14 years, allowing a classification and an evaluation of the values diffused in the media.

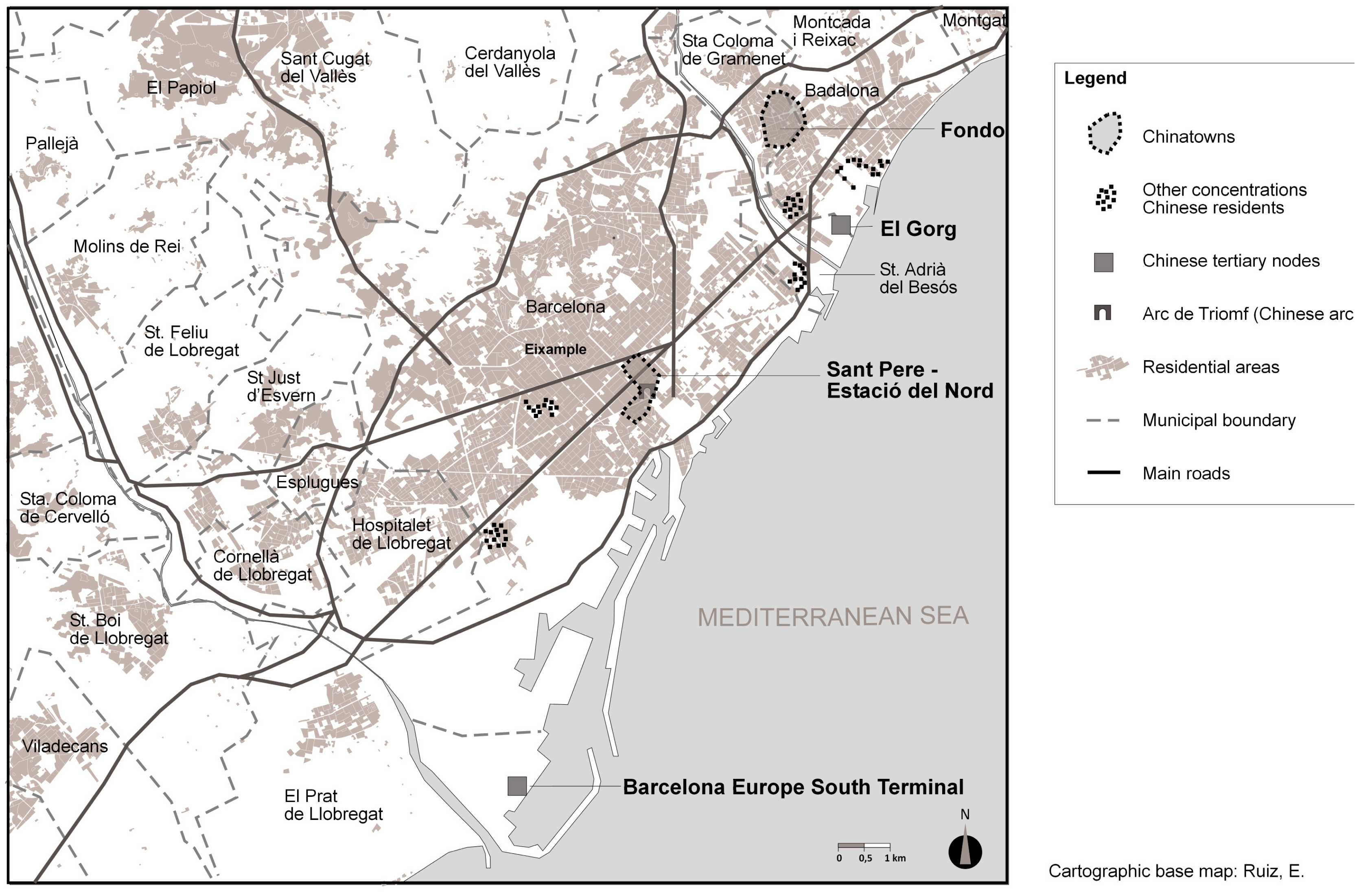

The traditional direct observation on the different Chinatowns in Metropolitan Barcelona (Fondo neighborhood in Santa Coloma de Gramanet and around the former Estació del Nord railway station), and the cartographic methodologies of geographers, together with a deep knowledge of the dynamics of the real-estate market, the authors have mainly supported the analysis.

3. On Globalization

Globalization has become real commonplace in all the economic, social, cultural, and political analyses, even more in the case of the urban studies. It is especially true since the publication of the first hypothesis of Saskia Sassen on global cities [

11]. The diffusion of the concept implies a multiplicity of conceptions, sometimes even contradictory, that contributes to a difficulty of definition of the complex process of integration of the global economy. From Sassen’s approach, the main emphasis was put into the dynamism of some big cities and in the supremacy of the financial capital, both connected in her study cases New York, London, and Tokyo, and further enlarged to many other big cities [

12]. However, the first conception of the globalization has been developed among the social historians, mainly by Immanuel Wallerstein in his fundamental analysis of the Modern World System [

13]. The concept aroused through the implementation of large-scale and a long-time points of view. Probably because of the homogenization consequences of the globalization processes, the concept has become very popular among sociologists, paradoxically more than among the economists who were very familiar with the traditional integration trends at a level of international trade and investments.

In the geography field, Peter Dicken published a pioneering study on the globalization of the economic system [

14]. From a critical point of view, Richard Peet analyzed the process as a societal development of capitalism itself [

15]. Outside of the Anglo-Saxon world, it is interesting to remark that many French scholars discuss the use of the term with preference to

mondialisation in accordance to the French roots of the quoted historical analysis, both the famous

Annales school or the work of Fernand Braudel [

16,

17]. The impact of the communications revolution based on the use of satellites, through computers, Internet, and cellular phones has allowed discussion about a real informational revolution that constitutes one of the strongest elements of the present globalization, probably more significant for the explanation of the social, cultural, and territorial changes. The Spanish sociologist, Manuel Castells, first analyzed this phenomenon at an urban scale [

18] before the publication of his important synthesis [

19]. As many other authors, he puts major emphasis on the technological aspects of the current revolution of economy, society, and time. The Brazilian geographer Milton Santos, in a similar direction, defined a new concept of nature as a technic-scientific-informational milieu based on the unicity of techniques that completes the definition of globalization [

20]. He also has elaborated a short analysis claiming for the building of alternatives to capitalist globalization, connecting the scientific explanation of the reality with the vindication of a more fair social system [

21]. Finally, in the field of the cultural anthropology, the cultural consequences of the globalization processes that too often appear as homogenization, could be understood as some kind of implicit form of imperialism, has been analyzed in depth by the Argentinian Garcia Canclini that defined the hybrid cultures dealing with modernity [

22].

This analysis is obviously too general, and needs to advance on different scales. A relatively naïve dualism can be observed in opinions about globalization itself. Many people interpret and describe globalization processes as “natural”, as if they were just another logical step in the evolution of humanity, and for this reason unobjectable, on the other side, many also are simply negationist, as demonstrates the many different antisystem organizations and protests. For this reason, it is more and more necessary to go forward in the analysis started by Milton Santos with a realistic evaluation of the positive aspects of the education, health, wellbeing, and comfort of the people connected with the globalization, not forgetting the negative aspects of general cultural homogenization and increasing social and economic disparities [

23].

This analysis needs to be completed with a geopolitical perspective because the complexity of the processes developed at a global scale. In this direction, it is necessary to put China, as the origin of the investments analyzed in this paper on the present international arena. The end of the dualism established between 1945 and 1989 does not imply any kind of unicity of the global political system. The “clash of civilizations” during the last decade of the twentieth century shows that simpler dualisms cannot explain the real complexity of current human society [

24]. The concept of BRICS (Brasil, Russia, India, China, South Africa) created by an economist from Goldman Sachs [

25] is not a real geopolitical category, but a conjunctural group of interests. Neither the old concept of the Third World, created in French sociology in the 1960s, nor the concept of the Fourth World including the poorest countries, are useful anymore: both are too general and simplistic. Russia maintains some elements of its former Soviet role at an international scale. The People’s Republic of China is not yet at the second pole, as in some way it is the heir of the Soviet Union. The balance of intense diplomatic work (with some important treaties like the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership or the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty) could be relevant and the permanent crisis of the European Union is not a minor element in this process of the reconstruction of the new political order.

The economic, cultural, and migratory expansion of China at the scale of Barcelona must be analyzed in this context.

4. On the Globalization of Real Estate Markets

Real estate markets were traditionally local until the final decades of the 20th century. A detailed analysis of evolutions and trends is required to understand their subsequent globalization. Global-financial dynamics and their local consequences must both be examined. Among the general lack of data, studies arising from different and significant cities around the world could afford important information on this process in order to put the evolution of urban land markets into the general theory.

Urban real estate plays a key role in the more general process of capital accumulation, as first pointed out by Henry Lefebvre [

26], and later discussed by David Harvey [

1]. The built environment, urban real estate, and the housing market should be considered in the frame of circuits of capital in advanced capitalism. In the search for constant accumulation of capital, a crisis of over-accumulation is avoided through spatial restructuring and credit expansion. Spatial restructuring requires a capital switch from the primary circuit of production to the secondary circuit of the built environment, and so urban real estate, and the city, is situated at the center of capital accumulation. In his classical essay, Logan and Molotch have described the city as a growth machine in this same way [

27]. This book has been reedited 20 years later with a new preface, and John R. Logan has also published an interesting book on Chinese cities [

28].

A process of internationalization of real estate has taken place at the same time as a process of internationalization and globalization of the economic system [

14], leading to capital accumulation at a global scale, and as a process of internationalization into the local real estate [

29]. Hence, capital switches from the first to the second circuit have gone beyond state limits and state economy. Some (mainly financial) international agents have created the right conditions for international capital flows. There is a discussion on the role of the state in this process, and it seems that in spite of the general weakening of states in front of globalization in general, at the level of the urban real estate this role has been very strong, at least in the case of the United States [

30]. Some international agents, mainly financial, have created the conditions for international capital flows, that the laws and regulation of the States has reinforced and encouraged. In this regard, the recent economic crisis, as shown in the subprime mortgage crisis starting in the USA [

31] and its diffusion to Europe and some other countries, has had an important impact.

The recession in Spain was triggered by the simultaneous occurrence of a general recession, rooted in the mortgage crisis of the USA, and the explosion of the Spanish real estate bubble [

32,

33]. It is not a conjunctural crisis, and is inextricably linked to the Spanish economic model and the “long wave” of the Spanish economy [

34]. Spain’s economic system, which is mainly based on tourism and the construction sector, was forged during the Franco regime in the 1940s and consolidated from the end of the 1990s, until it simply collapsed. The Spanish recession reveals the centrality of property in the Spanish economy [

35], which is also the case in other contexts, such as China, East Asia, or Japan, as shown by Fulong Wu [

36]. The housing sector, real estate, is connected directly with capital accumulation, and the wider economic system.

Japanese investment in American and British real estate markets was probably the first serious step in the globalization of ownership of urban buildings [

37,

38]. These investments were not included in the first circuit of capital, but were a result of the financial bubble [

39]. One explanation for this process could be that the weakness of Japan’s enormous industrial development after the end of the Second World War led to direct capital investment overseas, placing Japan at the top of the 1989 ranking [

40]. It would be interesting to examine whether other major foreign investments in real estate overseas, such as Chinese investments in this case study, have the same cycle of success and failure as Japanese investments.

The internationalization of Barcelona’s real estate market, through connection with global financial trends, began with the integration of Spain into the European Union in 1986 [

41]. The tourism economy of coastal areas and of the main towns and cities meant that this process has spread at different levels of investment. The official number of international tourists in Spain was 48.5 million in 2001 and 64.9 million in 2014 [

42]. The contemporary “brick bubble” that burst in Spain with the international recession in 2007 has stimulated foreign investments (

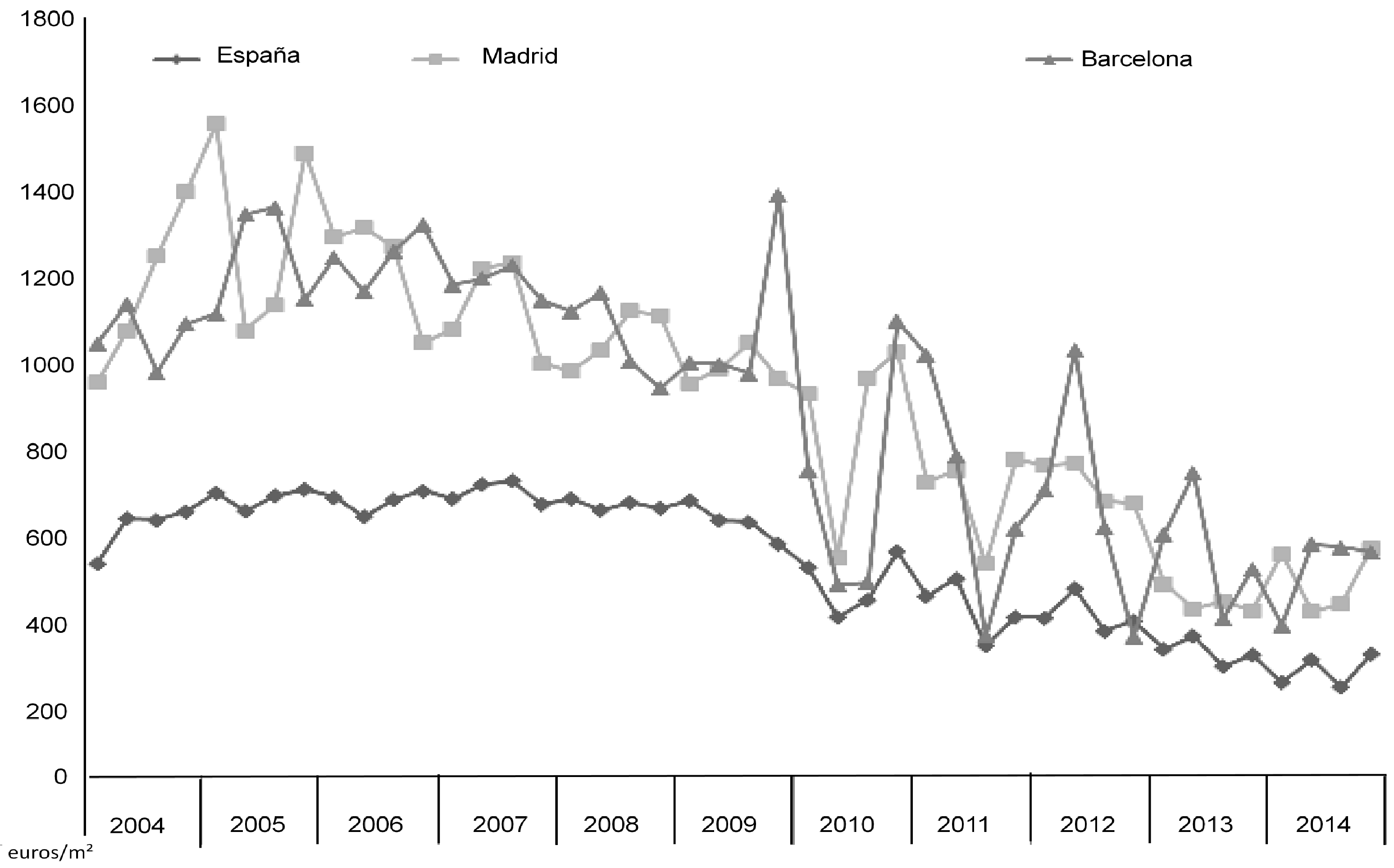

Figure 1). The price of second hand housing in Barcelona fell by 41.9% between 2008 and 2013, and that of new housing dropped by 36.6%, and was still falling in 2014. The nationality of foreign buyers is very similar to the composition of tourist flows (French, Dutch, British, and Italian), with a decline in Russian buyers after the ruble collapsed, and a significant proportion of Chinese investors. The implementation of the well-known “golden visa” law in Spain at the end of 2013 could reinforce this kind of investment. The “golden visa” was established in September 2013, with a minimum of €500,000 established for any kind of investment. According to press reports during the first 15 months of implementation of the law, the total amount of golden visa investment in Spain was €369.7 million compared to 1100 in Portugal [

43].

The main actors in this kind of emigration are the more-or-less official Chinese emigration agencies and the lawyer’s offices that act as intermediaries with local real estate companies.

At the beginning of 2016, the real situation was a very fragmented housing market, where the Chinese played a very interesting role.

5. The Fragmentation of the Real Estate Market

The fragmentation of urban land markets is due to at least two factors. First, we must differentiate between three types of property from a functional point of view: residential, which constitutes the main focus of this paper; industrial/production; and commercial (retail/offices). Second, in terms of Chinese demand, investors in properties for production must be divided into elite investors seeking a golden visa, and local diaspora investors both the different typologies and this social segmentation produces a very fragmented real-estate market even regarding a unique ethnic community.

Investors in production appear to be strongly connected to the general strategies of the People’s Republic of China [

44]. Although these strategies are not always well-known, and are regulated by at least eight official institutions, there are two public banks that channel public resources for foreign investment [

45]. China’s foreign investment has grown in recent years, since at least 2000, when the policy “Go Global” was incorporated into the 10th (2000–2005) and 11th (2005–2010) Five-Year Plan by the Chinese Government. If we consider data on foreign direct investment, China is currently the second most important country in the world [

46], and accounts for more than 18,000 enterprises overseas. Most of them are public enterprises, and only a few are private, such as Hutchinson Wampoa, the Hongkonesee Company investing in Barcelona.

Between 2005 and 2013, China’s investment in real estate was the fourth highest in the world, after energy and power, metals, and finance [

47]. Moreover, China’s investment in Europe experienced faster growth from 2013 onwards, mainly in sectors such as real estate. Europe emerged as one of the top destinations for Chinese foreign investment globally [

48]. Some of the investment in Europe is due to the ideal geo-economic position of the Mediterranean sea for goods’ transportation from China to Europe, as the “old continent” is the main market for China’s goods. This explains Chinese companies’ recent investment in the transport sector and logistics [

49]. Notably, in 2009, a container terminal was purchased in Piraeus harbor, in Greece, by Cosco, a Chinese state company. Despite its economic crisis, Greece is likely to become the main entry point for China’s goods to Europe. The same logic could explain the investment of 800 million euros in Barcelona’s port, in a new container terminal named BEST (Barcelona Europe South Terminal), by the private company Hutchinson. Approved in 2006, the terminal began operation in 2012, and is now being enlarged.

Chinese commercial investments are strongly related to residential investments [

44]. It is not yet clear whether the initiative is due to the actions of individual citizens or is to some extent directed by the political strategies of the People’s Republic of China. The key factor for answering this question lies in the maintenance of the official limit to the total amount of Chinese capital that can be taken out of the country annually, at $50,000 per capita and per year, according to Hurun Report, one of the most important Chinese business magazines [

50].

Therefore, two Chinese communities are acting in the Barcelona real estate market today, with different strategies and consequences for the local housing market. The most recent group of golden visa investors are members of the Chinese economic elite or high level government employees who buy new apartments in the center of the city or in some of the wealthy suburbs, and have no connection with any other investment. Even though they do not plan to live in the city in the short-term, they use their houses temporarily or rent them while waiting for retirement or a worsening of living conditions in China.

The second community is comprised of Chinese people who live and work in Barcelona. This community could also be divided into different groups. The first group is that of Chinese people connected to universities or with executive jobs in private companies (advisors, translators and managers). This group acts in a very individual way, like other foreign people or even the same local social group, with a remarkable level of cultural integration. Second, and very similar to this first group, are Chinese children adopted by local families [

51]. Between 1997 and 2007, a total of 12,408 Chinese children were adopted throughout Spain, forming the first community of international adoptions. Since 2007, the numbers of internationally adopted children have been declining, probably because of the impact of the recession on families’ everyday lives [

52]. Third, is the group of people in the diaspora who arrive with family capital to invest in small to medium-sized private businesses. This third group constitutes the main focus of our paper and requires deeper analysis.

6. Chinese Residential Strategies in the Barcelona Metropolitan Area

The immigration of Chinese people in Barcelona, as in Spain in general, is a very recent phenomenon. Spain has traditionally been a country of emigration until the last decades of the twentieth century. A relevant Latin American political immigration in the 1970s, with some well-known writers—the two Nobel prize winners, Garcia Márquez and Vargas Llosa, are the most famous of them, but there were many others like the Argentinian Cortázar or the Chilean Bolaño—and artists has prefigured a first and dramatic change in the direction of the migratory trends. In the 1990s, an important flow of labor migrants coming from Latin America (especially from Ecuador, Colombia, and Bolivia), Africa (mainly from Morocco and Senegal), and Asia (mainly from the Philippines and Pakistan) has changed the demographic structures of the majority of Spanish regions and its cities, that has been stopped with the beginning of the economic crisis in 2008 [

53].

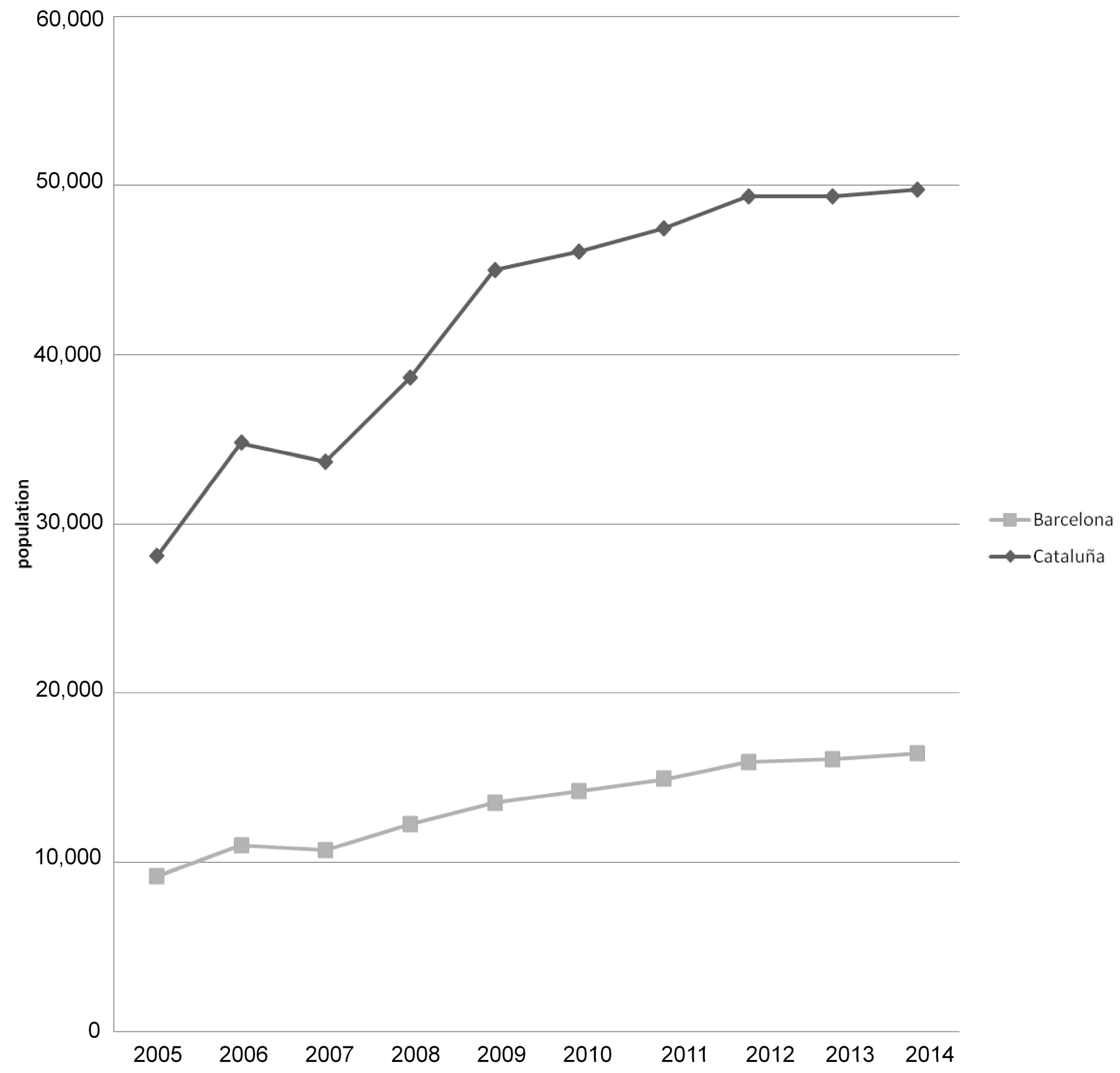

Chinese immigration almost coincided with the beginning of the new century in many of the municipalities of the Barcelona’s Metropolitan Area (AMB). In 2000, there were only 4900 Chinese people officially registered, more than two-thirds in the municipalities of Barcelona and Santa Coloma de Gramenet. This community has been growing annually, and reached 31,326 people in 2014 in the whole AMB, with the same proportion in the two quoted localities. The number of Chinese people has increased six fold between 2000 and 2014, and remains until today the only foreign community with constantly increasing numbers (

Figure 2). It is probably not a great Chinese community, if compared with other cities around the world, but it already appears as a very relevant new social element that requires detailed analysis [

54].

Barcelona is a very interesting case study. At the beginning of the 20th century, especially during the years of the First World War—the neutrality of Spain in the war enabled Barcelona’s manufacturers to trade with the two powers in a very conflictive landscape of espionage and big business—the popular district around the harbor was occupied by leisure and marginal activities (prostitution, drugs, music halls, and others). In spite of the local name for this district, a French journalist dubbed it the

Barrio Chino as its atmosphere was very similar to the Chinatowns on the western coast of the United States. It is important to remark that the meaning of "barrio chino" in Spanish is not “Chinatown” in English. It cannot be understood as a literal translation, it has another meaning. Although no Chinese people lived in this neighborhood at the time, the name stuck in international literature and cinema, and in the collective conscience of the Barcelona people [

55,

56,

57]. Urban planning and urban policies have periodically tried to clean up this part of the city and finally they succeeded right at the end of the century, when many North African and Asian (but not Chinese) immigrants had already colonized the area [

58].

The first public emergence of a Chinese community in the city was detected at the beginning of the 21st century, 100 years after the emergence of the

Barrio Chino. The traditional textile wholesale shops in the new Sant Pere neighborhood [

59] were progressively bought by Chinese people, as in many other European cities. Chinese immigrants maintain this traditional activity, with products that are now mainly produced in China. Some local residents reacted in an (also traditional) xenophobic way, and mainly criticized the activity rather than the people [

5]. From 2001 to 2010, at least 13 relevant articles on the conflict were published in

La Vanguardia. Chinese associations came together to resolve the conflict, at the same time as increasing numbers of Chinese immigrants arrived and moved into the surrounding areas and some other parts of the Metropolitan Area. Finally, in 2015, the local leader of the protest joined the board of the Chinese women’s association as a cultural advisor, as a big gesture of peace making.

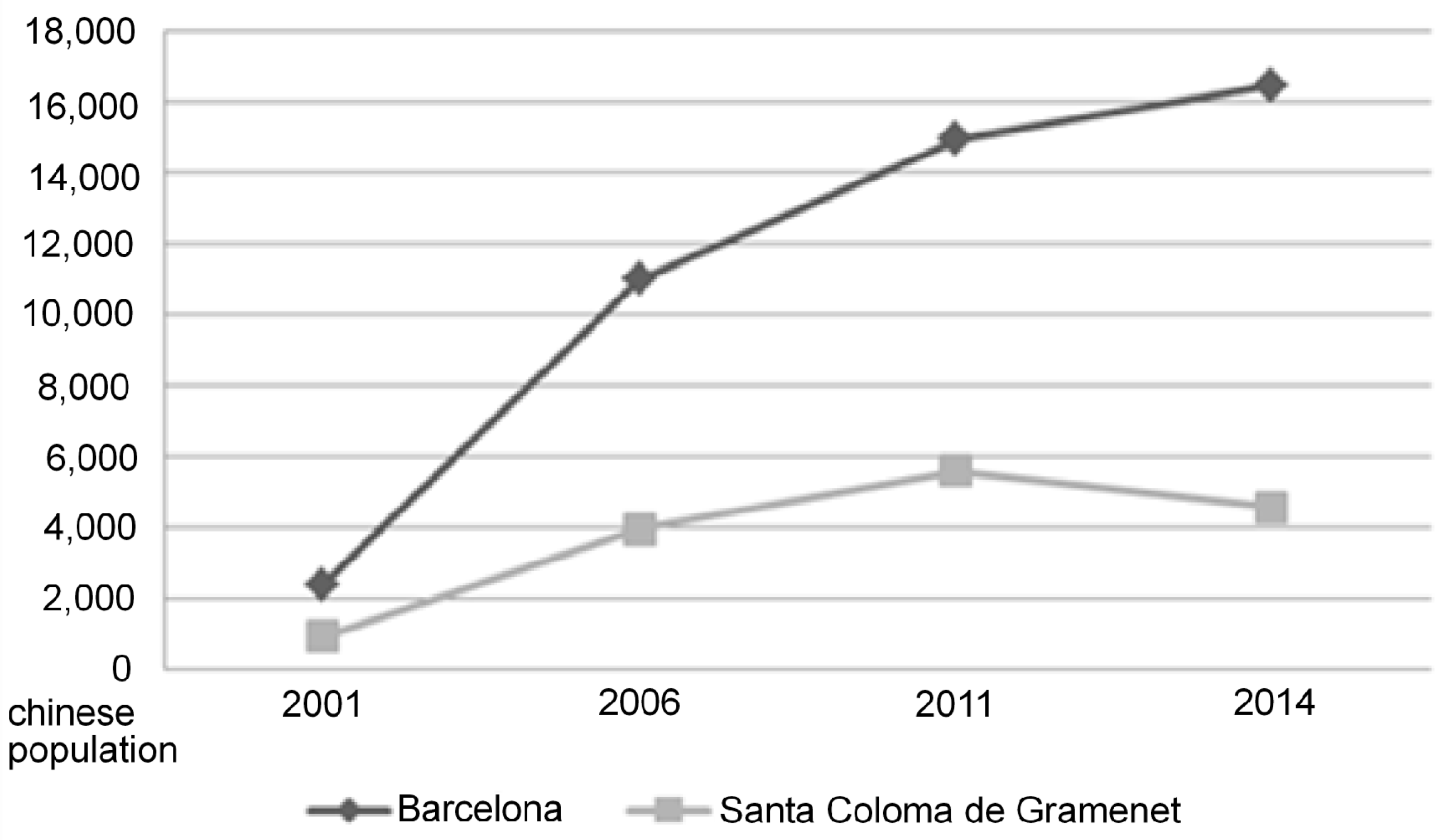

In the official census of 2001, there were 2418 Chinese people in the city of Barcelona, and 930 in the municipality of Santa Coloma de Gramenet, mostly in the Fondo neighborhood. Five years later, the figures in municipal records were 10,986 and 3962, respectively. Therefore, there was a five-fold growth in Barcelona, and a four-fold increase in Santa Coloma de Gramenet, especially in Fondo neighborhood. From the information data arising of different interviews and fieldwork it could be said that the main residential strategy of immigrants was to live as close as possible to their Chinese businesses.

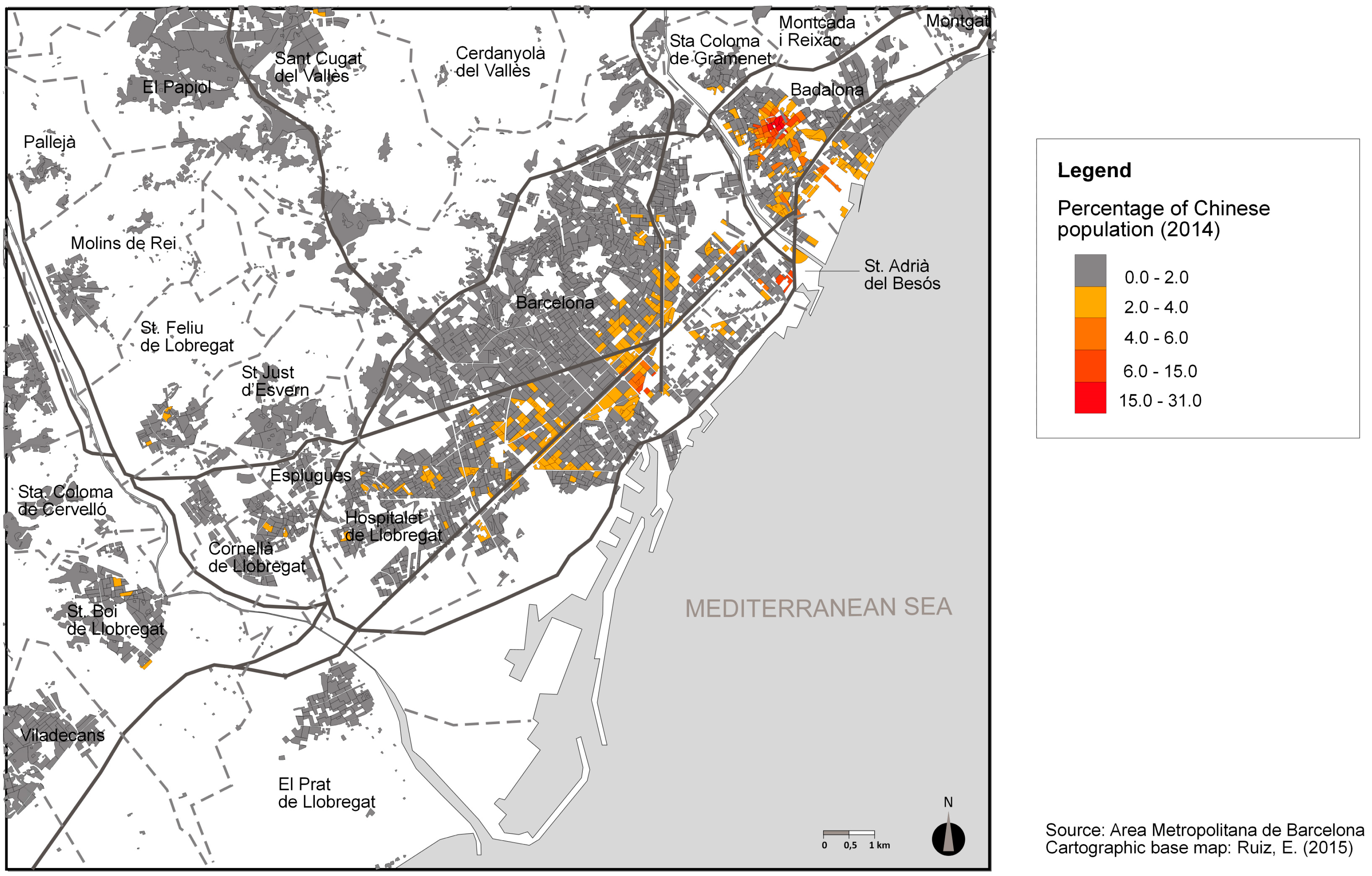

Therefore, from a spatial point of view, this signaled the start of two different Chinatowns in the eastern part of the Metropolitan Area: one in Barcelona around the Arc de Triomf (around 15% of registered people are Chinese people) near the traditional textile wholesale shops in the Sant Pere neighborhood, and the other in the already quoted neighborhood of Fondo, in Santa Coloma de Gramenet, (between 15% and 30% of registered people are Chinese in the central parts of this neighborhood) (

Figure 3). The area of Fondo was the first to ask for a Chinese gate, according to the traditional model of Chinatowns. This area has a high density of Chinese people living in relatively poor houses, as well as Chinese restaurants, shops, and services mainly frequented by Chinese people. The request for a gate was refused. The Chinese population of Fondo continued to increase until 2011, when it reached a peak of 5585 inhabitants. Since then, it has decreased slightly, though there is still a very visible concentration of Chinese inhabitants on maps and in the landscape.

In contrast, the Chinese population in Barcelona has continued to increase until today. As it has already been remarked, this is the only foreign community that grew during the years of the recession, although there has been a slowdown. At the end of 2014, there were 16,435 Chinese people in Barcelona (

Figure 4). Public opinion is not as xenophobic as it was at first, but is almost always connected to negative aspects. In all the newspapers, there are stories connected to prostitution, mafia, drugs, and illegal games. The analysis of the news published in the already quoted

La Vanguardia demonstrates an intense interest on the Barcelona’s Chinese population and their activities. In 1986, 993 stories related with Chinese people were published and, in 2014, this number has risen to more than 2000. The general trend has been the constant growth, with some maximums in 1989, 1992, or 1998. The recent news, since the year 2000, has been analyzed for its content and the discourse produced. It is possible to identify five different groups of topics: (1) conviviality problems, with both a positive or negative evaluation; (2) big investments of Chinese capitals; (3) retail activities, also positively or negatively evaluated; (4) criminality and illegal activities; and (5) a diversity of news regarding the increase of Chinese population in some parts of the city or other various topics, in general positive information.

In these 14 years, the discourse has notably changed. At the beginning of 2000, the stories dealt with conviviality problems, concerning the commercial competition with other local retailers. After 2003, this discourse became more and more connected to Chinese criminal activities (fraud, forgery, or labor exploitation). However, since 2005, also it is possible to identify a new story related to the commercial dynamism of the Barcelona’s Chinese firms. In fact, it appears the increasing image of the P.R. of China is as a big economic power, connected to the biggest Chinese investments, like the harbor infrastructure. In spite of this change into the orientation of the public discourse, both positive and negative opinions are maintained. It seems that it is strategic to differentiate the first Chinese residents from the new big investors and tourists. In conclusion, far from the international public rejection of the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989, the impressive economic rise of People’s Republic of China seems to have contributed to the amelioration both of the local public opinion and of the self-respect of Chinese people. These data comes both from selected interviews and from the analysis of the newspapers’ discourses [

60].

Many of the newly arrived Chinese people live very close to the textile wholesale area, around the former Estació del Nord railway station. A real Barcelona Chinatown has developed, with a concentration of Chinese people and businesses (

Figure 5). The majority of people are from the southern part of the Zhejiang province, from the district of Qingtian and the city of Wenzhou [

61]. After the failed Fondo initiative to build a Chinese gate, many Chinese people more or less consciously adopted the 19th century Arc de Triomf as their own gate. Many days at dawn, Chinese people can be seen doing tai chi on the grass around the arch. More symbolic is the fact that the official celebration of Chinese New Year in 2015 took place in front of it. Tourist policies for a Chinatown in the city have not yet been considered, unlike many other cities in the world [

5]. Even the Chinese people and their associations do not appear to be very interested in the construction of a more classical Chinatown. They seem to be more concerned with a process of social integration into a western way of life, and into Barcelona’s traditions.

Another concentration of visible Chinese activities can be found on the border of the municipalities of Sant Adrià del Besòs and Badalona. These areas contain many warehouses for a range of products, not just textiles: sports, home, food, electronics, and jewelry [

62]. Most of the owners and workers live in Fondo, but the clients are not just Chinese shoppers in the region: many are non-Chinese buyers from all around Catalonia and even the south of France (

Figure 6).

In June, 2010, the Confucius Institute of Barcelona was created to consolidate Chinese cultural diffusion in the entire autonomous region of Catalonia. The Confucius Institute of Barcelona was first organized as a foundation with the involvement of three universities (the University of Barcelona, the Autonomous University of Barcelona, and Beijing Foreign Studies University) and Casa Asia (a public institution of the Spanish Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the municipality of Barcelona). This means that its activities can extend beyond the traditional academic tasks of the other institutes, and it has gained official recognition with the Hanban prize of the Institute Confucius of Excellence in December 2014. It is just one of 443 Confucius Institutes worldwide at the beginning of 2015, and clearly indicates one strategy of the Chinese government. The diffusion of Chinese language and culture was firmly established by this Institute, while academic exchanges are increasing every year. Many of the Chinese students who come to Barcelona try to stay in the city on completion of their courses, working as advisors, translators, or even administrative staff for Chinese firms and business. These people develop a residential strategy that is very similar to the same level of locals.

In addition to the two aforementioned Chinatowns, another clear pattern can be observed in the location of the Chinese population in the Barcelona Metropolitan Area: the dispersion of Chinese all around the central districts. This could be explained by various factors. One is that some Chinese residents in Barcelona have been quite successful in their business. This increasingly large group seeks to improve their living conditions in bigger, better apartments. Proximity to their businesses continues to be their main strategy for location, but the new factor is the radical change in their businesses. There are still some typical Chinese bazaars, but normally these Chinese residents buy bars and restaurants that they keep as they were, with the same specialties as before. The owners and workers—the workers are members of the family or used to live in the same apartment as the owner, in a very traditional way—are Chinese, but the businesses offer typical regional products from Spanish regions, especially observed in tapas restaurant (the typical Spanish-style appetizers). This is the beginning of what is in some way a silent Chinatown, as also seems to be the case in some parts of Paris. It is a form of the clear integration of many successful Chinese people into Barcelona’s social and spatial structure.

Other than proximity to businesses, the strategies for residential location of any group of Chinese people remain relatively obscure. Of course, price plays an important role, but some traditional superstitions, like Zen orientation, or the good and bad luck associated with houses’ street numbers are also factors. Men mainly take the initiative, but the final decision remains in the women’s hands. Comfort and even luxury are introduced progressively as important concepts in this process of social integration of former socialist citizens into capitalist cities [

63].

Thus, some of Barcelona’s Chinese people are becoming progressively similar to the increasing number of Chinese tourists, who are regarded as one of the highest spending tourists in Spain. The figures for Chinese tourists in Barcelona in 2013 were 73,906, only less than 1% of the total number of tourists, but their spending per capita was €1132.2 which makes them the second biggest spending nationality, behind the Americans. This is one indicator of the same process of class differentiation found in the People’s Republic of China itself.

7. Main Conclusions

The first conclusions are that we should be wary of simplifying and unifying a very complex reality. China is a vast, diverse country, both culturally and socially, with a very long, rich history. In addition to the increasing population of China itself, there are many communities of Chinese people overseas. These communities also have long, diverse histories in different parts of the world. This factor, which is not always seriously considered, means that the word “Chinese” could be interpreted as a reductionist, local construct that tends to simplify different cultural, social, and geographical realities. This simplification is the basis of the ignorant, xenophobic discourses that are often found in the media. Chinese expansion in the Pacific and the Indian Ocean Rim is distinct from the 19th century Chinese emigration to the western coast of the United States or the forced emigration to Spanish Cuba. Likewise, people escaping from the Chinese communist revolution have little in common with the diaspora in the times of the “One Country, Two Systems” principle. This diaspora is associated with the recent phenomenon of Chinese immigration to Barcelona, which is just beginning to be studied.

The second conclusion concerns the Chinatowns in Barcelona. Regarding the relevance of the Chinese inhabitants in the urban space in Barcelona, it should be stressed that Chinatowns are different than in the North American and South-Eastern cities. As in other European cities [

64], in spite of the concentration of Chinese migrants in some neighborhoods, their origin of Chinatowns is different from those found in other continents. The particuliarity in Europe is that the Chinese community does not tend to form separate neighborhoods, creating urban enclaves characterized by Chinese cultural symbols. Despite this, the neighborhood of Fondo has tried the construction of an arch, which was refused by the local community.

In the case of Barcelona, there are some particularities. The Chinatown in Barcelona is based on immigrant flows that acquire a relevant dimension especially at the beginning of the 21st century. The settlement has, therefore, a relatively short history of settlement in the city. Those particularities separate it from the traditional model of Chinatown, and bring it closer to what has been termed as a postmodern Chinatown [

65]. In the case of Barcelona, the Chinese communities have tried to integrate in the urban space of the city through their melting in the general residential market. Although, in certain neighborhoods, Chinese inhabitants may be quite abundant their presence is in general unnoticed, as we have previously discussed.

The third conclusion is that the present Chinese system should be regarded as market socialism [

2]. In contrast to the late capitalism of the market in the Western world and the capitalism of the state in the former Soviet Union, China has emerged with its own productivist economic system controlled by one Communist party, with a plan to move from the role of world manufacturer to that of a mass consumption society. Consequently, the egalitarian society will be transformed into a new class-based society, which involves an internal process of dramatic urbanization of the population, and an external process of integration of the diaspora in Western societies, with strong connections to the mainland.

From this second conclusion, two other conclusions can be drawn that are as ambitious as they are impossible to verify. One is related to the impressive economic expansion of China. The other is related to the political consequences of the process itself.

The third conclusion can only be formulated at the level of a general hypothesis. The main challenge is whether it is possible for the People’s Republic of China to maintain its predominantly high position in all production rankings. The recent reduction in growth rates could herald the decline of the Chinese model, and its replacement by another global power. Similarly, in spite of the many structural differences, we could compare foreign investments in China with the rise and fall of Japanese foreign investments in the last century.

Finally, the fourth conclusion regards the geopolitical dimension of the current Chinese expansion worldwide, which is still an open question. It is impossible to draw general conclusions from one case study. The scale of studies on Chinese expansion in Europe and even in the West (including the important case of Australia) should be increased. This European and Western expansion has followed a very different strategy from that of African and Latin American investments, which have reached enormous amounts of capital in many different economic sectors, especially raw materials and infrastructures. Chinese investment in foreign real estate has begun in the USA, Europe, and Australia and could continue in Spain.

This paper indicates that more in-depth research is required in this area, as the question has not yet been answered.