Effect of Irrigation Water Quality and Soil Compost Treatment on Salinity Management to Improve Soil Health and Plant Yield

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

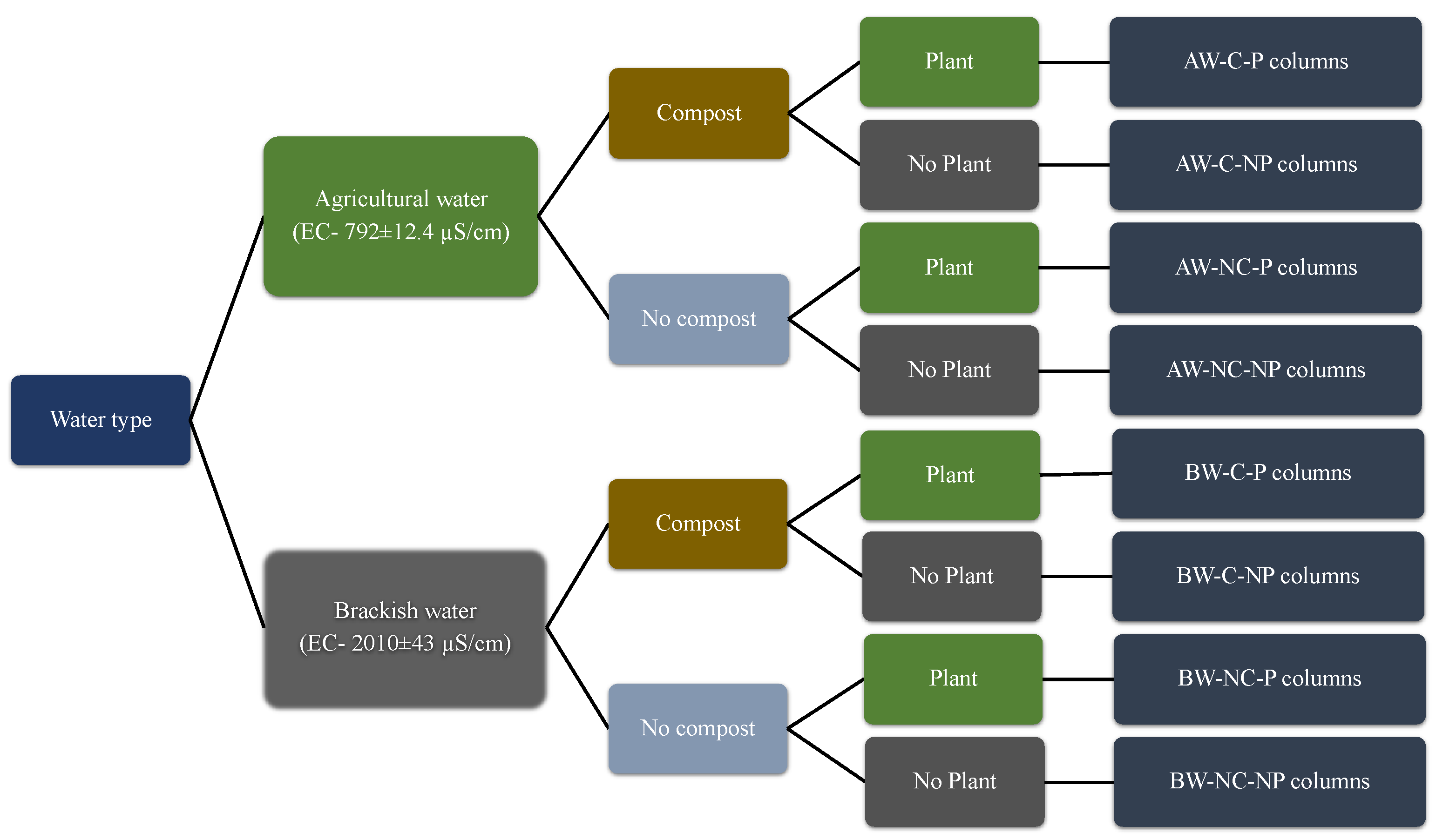

2.1. Experimental Design

2.2. Physicochemical Analysis of Irrigation Water, Leached Water, Soil, and Plants

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Impact of Compost Treatment on Soil Moisture Content and Soil EC

3.2. Impact of Compost Treatment on Leaching of Ions and Organics from Soil

3.3. Impact of Compost Treatment on Soil Compositions

3.4. Impact of Compost Treatment on Reduction in Nutrient Leaching

3.5. Impact of Plants on Nutrient Leaching

3.6. Impact of Compost on Plant Yield, Soil, and Leaching of Ions from the Soil Profile

| Irrigation Water Type | Soil Treatment | Fresh Weight of Biomass (g) | Dry Biomass (g) | Plant Height | Root Length (cm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (cm) | |||||

| Impact of compost-treated soil on different types of water irrigation and percentage increase in the plant growth measures in harvested plants | |||||

| Brackish water | No compost | 11 ± 2.3 ab | 2.1 ± 0.3 a | 114 ± 11.9 a | 19 ± 0.4 c |

| Brackish water | Compost | 18 ± 2.0 a | 3.1 ± 0.8 a | 132 ± 3 a | 42 ± 2 a |

| Compost/No compost | 63.60% | 50.00% | 15.80% | 121.10% | |

| Agricultural water | No compost | 10 ± 2.0 b | 1.87 ± 0.2 a | 118 ± 8.6 a | 33 ± 5 b |

| Agricultural water | Compost | 15 ± 4.2 ab | 3.2 ± 0.9 a | 128 ± 14.6 a | 37 ± 1 ab |

| Compost/No compost | 50.00% | 50.00% | 8.50% | 12.10% | |

| p-value | C | 0.006 | 0.010 | 0.058 | 0.000 |

| IW | 0.246 | 0.890 | 1.000 | 0.015 | |

| CxIW | 0.688 | 0.680 | 0.527 | 0.000 | |

| Impact on percentage increase in the plant growth measures in harvested plants with varying irrigation water types | |||||

| Agricultural water/Brackish water (No-compost columns) | −9.10% | 0.00% | 3.50% | 73.70% | |

| Agricultural water/ Brackish water (Compost-treated columns) | −16.70% | 0.00% | −3.00% | −13.50% | |

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pitman, M.G.; Läuchli, A. Global impact of salinity and agricultural ecosystems. In Salinity: Environment-Plants-Molecules; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2002; pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Phour, M.; Sindhu, S.S. Soil Salinity and Climate Change: Microbiome-Based Strategies for Mitigation of Salt Stress to Sustainable Agriculture. In Climate Change and Microbiome Dynamics: Carbon Cycle Feedbacks; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 191–243. [Google Scholar]

- Khasanov, S.; Kulmatov, R.; Li, F.; van Amstel, A.; Bartholomeus, H.; Aslanov, I.; Sultonov, K.; Kholov, N.; Liu, H.; Chen, G. Impact assessment of soil salinity on crop production in Uzbekistan and its global significance. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2023, 342, 108262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewster, J. Flowering and Seed Production in Overwintered Cultivars of Bulb Onions: I. Effects of Different Raising Environments, Temperatures and Daylengths. J. Hortic. Sci. 1982, 57, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corwin, D.L. Climate change impacts on soil salinity in agricultural areas. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2021, 72, 842–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, R.C.; Velasco-Cruz, C.; Darapuneni, M.; Montgomery, R.; Grant, L. Southwest-adapted maize germplasm as a potential genetic resource for selection of salinity tolerant cultivars. Crop Sci. 2022, 62, 286–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M.I.; Farooq, M.; Muscolo, A.; Rehman, A. Crop diversification and saline water irrigation as potential strategies to save freshwater resources and reclamation of marginal soils—A review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 28695–28729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welle, P.D.; Mauter, M.S. High-resolution model for estimating the economic and policy implications of agricultural soil salinization in California. Environ. Res. Lett. 2017, 12, 094010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalcante, E.S.; Lacerda CFd Costa, R.N.T.; Gheyi, H.R.; Pinho, L.L.; Bezerra, F.M.S.; de Oliveira, A.C.; Canjá, J.F. Supplemental irrigation using brackish water on maize in tropical semi-arid regions of Brazil: Yield and economic analysis. Sci. Agrícola 2021, 78, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillel, D. Salinity Management for Sustainable Irrigation: Integrating Science, Environment, and Economics; World Bank Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Anikwe, M. Soil Management for enhanced crop productivity. In Proceedings of the 57th Annual General Meeting of the Association of Deans of Agriculture in Nigerian Universities (ADAN), Abakaliki, Nigeria, 15–18 June 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Mohanavelu, A.; Naganna, S.R.; Al-Ansari, N. Irrigation induced salinity and sodicity hazards on soil and groundwater: An overview of its causes, impacts and mitigation strategies. Agriculture 2021, 11, 983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Hur, M.; Shainberg, I.; Bakker, D.; Keren, R. Effect of soil texture and CaCO3 content on water infiltration in crusted soil as related to water salinity. Irrig. Sci. 1985, 6, 281–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemper, W.; Rosenau, R. Aggregate stability and size distribution. In Methods of Soil Analysis: Part 1 Physical and Mineralogical Methods; American Society of Agronomy, Inc.: Madison, WI, USA, 1986; Volume 5, pp. 425–442. [Google Scholar]

- Tessema, N.; Yadeta, D.; Kebede, A.; Ayele, G.T. Soil and irrigation water salinity, and its consequences for agriculture in Ethiopia: A systematic review. Agriculture 2022, 13, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornes, F.; Belda, R.M.; Carrión, C.; Noguera, V.; García-Agustín, P.; Abad, M. Pre-conditioning ornamental plants to drought by means of saline water irrigation as related to salinity tolerance. Sci. Hortic. 2007, 113, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwiczak, A.; Osiak, M.; Cárdenas-Pérez, S.; Lubińska-Mielińska, S.; Piernik, A. Osmotic stress or ionic composition: Which affects the early growth of crop species more? Agronomy 2021, 11, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, S.; Zhou, B.; Wang, Q.; Tao, W. Evaluation of irrigation water salinity and leaching fraction on the water productivity for crops. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2020, 13, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beecher, H. Effect of saline water on rice yields and soil properties in the Murrumbidgee Valley. Aust. J. Exp. Agric. 1991, 31, 819–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kranz, C.N.; McLaughlin, R.A.; Johnson, A.; Miller, G.; Heitman, J.L. The effects of compost incorporation on soil physical properties in urban soils–A concise review. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 261, 110209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cogger, C.; Hummel, R.; Hart, J.; Bary, A. Soil and redosier dogwood response to incorporated and surface-applied compost. HortScience 2008, 43, 2143–2150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadshirazi, F.; McLaughlin, R.A.; Heitman, J.L.; Brown, V.K. A multi-year study of tillage and amendment effects on compacted soils. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 203, 533–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weindorf, D.C.; Zartman, R.E.; Allen, B. Effect of compost on soil properties in Dallas, Texas. Compost. Sci. Util. 2006, 14, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggelides, S.; Londra, P. Effects of compost produced from town wastes and sewage sludge on the physical properties of a loamy and a clay soil. Bioresour. Technol. 2000, 71, 253–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masmoudi, S.; Magdich, S.; Rigane, H.; Medhioub, K.; Rebai, A.; Ammar, E. Effects of compost and manure application rate on the soil physico-chemical layers properties and plant productivity. Waste Biomass Valorization 2020, 11, 1883–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gates, T.K.; Cody, B.M.; Donnelly, J.P.; Herting, A.W.; Bailey, R.T.; Mueller Price, J. Assessing selenium contamination in the irrigated stream–aquifer system of the Arkansas River, Colorado. J. Environ. Qual. 2009, 38, 2344–2356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jayakumar, M.; Surendran, U.; Raja, P.; Kumar, A.; Senapathi, V. A review of heavy metals accumulation pathways, sources and management in soils. Arab. J. Geosci. 2021, 14, 2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, T.J.; Han, K.J.; Muir, J.P.; Weindorf, D.C.; Lastly, L. Dairy manure compost effects on corn silage production and soil properties. Agron. J. 2008, 100, 1541–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, N.; Flury, M.; Hinman, C.; Cogger, C.G. Chemical and Physical Characteristics of Compost Leachates. A Review Report Prepared for the Washington State Department of Transportation; Washington State University: Puyallup, WA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Zlotopolski, V. Magnetic treatment reduces water usage in irrigation without negatively impacting yield, photosynthesis and nutrient uptake in lettuce. Int. J. Appl. Agric. Sci. 2017, 3, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, T.T.K.; Le, T.H.; Tran, C.-S.; Nguyen, P.-T.; Thai, V.-N.; Bui, X.-T. Compost to improve sustainable soil cultivation and crop productivity. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2022, 6, 100211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, A.A.; Chowdhury, S.; Schlager, V.; Oliver, A.; Puissant, J.; Vazquez, P.G.; Jehmlich, N.; von Bergen, M.; Griffiths, R.I.; Gleixner, G. Soil fungal: Bacterial ratios are linked to altered carbon cycling. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Ataka, M.; Kominami, Y.; Yoshimura, K.; Kitayama, K. A constant microbial C/N ratio mediates the microbial nitrogen mineralization induced by root exudation among four co-existing canopy species. Rhizosphere 2021, 17, 100317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.C. The influence of soil microbial community structure on carbon and nitrogen partitioning in plant/soil ecosystems. PeerJ Preprints 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, M.I.; Mujawar, L.H.; Shahzad, T.; Almeelbi, T.; Ismail, I.M.; Oves, M. Bacteria and fungi can contribute to nutrients bioavailability and aggregate formation in degraded soils. Microbiol. Res. 2016, 183, 26–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Hasini, S.; De Nobili, M.; El Azzouzi, M.; Azim, K.; Douaik, A.; Laghrour, M.; El Idrissi, Y.; El Alaoui El Belghiti, M.; Zouahri, A. The influence of compost humic acid quality and its ability to alleviate soil salinity stress. Int. J. Recycl. Org. Waste Agric. 2020, 9, 21–31. [Google Scholar]

- Duong, T.T.T. Compost Effects on Soil Properties and Plant Growth. Ph.D. Thesis, School of Agriculture, Food and Wine, Adelaide, Australia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Malik, Z.; Malik, N.; Noor, I.; Kamran, M.; Parveen, A.; Ali, M.; Sabir, F.; Elansary, H.O.; El-Abedin, T.K.Z.; Mahmoud, E.A.; et al. Combined Effect of Rice-Straw Biochar and Humic Acid on Growth, Antioxidative Capacity, and Ion Uptake in Maize (Zea mays L.) Grown Under Saline Soil Conditions. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2023, 42, 3211–3228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadshirazi, F.; Brown, V.; Heitman, J.; McLaughlin, R. Effects of tillage and compost amendment on infiltration in compacted soils. J. Soil Water Conserv. 2016, 71, 443–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faucette, L.; Jordan, C.; Risse, L.; Cabrera, M.; Coleman, D.; West, L. Evaluation of stormwater from compost and conventional erosion control practices in construction activities. J. Soil Water Conserv. 2005, 60, 288–297. [Google Scholar]

- Favaretto, N.; Cherobim, V.F.; de Medeiros Silveira, F.; Timofiecsyk, A.; Skalitz, R.; Barth, G.; Pauletti, V.; Dieckow, J.; Vezzani, F.M. Can application of liquid dairy manure onto no-tillage oxisols reduce runoff, sediment, phosphorus, and nitrogen losses over 9 years of natural rainfall? Geoderma 2022, 405, 115406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, D.; Fransen, S.; Bary, A.; Cogger, C. Fertilizer nitrogen replacement value of food residuals composted with yard trimmings, paper or wood wastes. Compost. Sci. Util. 1998, 6, 6–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoitink, H.A.; Grebus, M.E. Status of biological control of plant diseases with composts. Compost. Sci. Util. 1994, 2, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, N.; Crohn, D.M. Compost induced soil salinity: A new prediction method and its effect on plant growth. Compost. Sci. Util. 2012, 20, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D. Johnson Su Bioreactor. March 2016. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DxUGk161Ly8 (accessed on 18 November 2022).

- Duzdemir, O.; Kurunc, A.; Unlukara, A. Response of pea (Pisum sativum) to salinity and irrigation water regime. Bulg. J. Agric. Sci. 2009, 15, 400–409. [Google Scholar]

- Mazumder, P.; Akhil, P.; Khwairakpam, M.; Mishra, U.; Kalamdhad, A.S. Enhancement of soil physico-chemical properties post compost application: Optimization using Response Surface Methodology comprehending Central Composite Design. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 289, 112461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, A.; Fatima, Q.U.A.; Umer, T.; Nazeer, S.; Irum, A.; Ullah, G.; Butt, B.; Khan, A.A.; Saddozai, U.K.; Ullah, S.; et al. Manure additions in different texture soils to enhance maize root penetration. Pak. J. Biotechnol. 2023, 20, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laboratory, A.A.S. Compost Analysis Report; The Pennsylvania State University: University Park, PA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Crohn, D.M. Assessing Compost Quality for Agriculture ANR publication 8514; University of California: Richmond, CA, USA, 2016; p. 12. [Google Scholar]

- Prajapati, J. The essential nutrient element for the crop. Int. J. All Res. Writ. 2019, 1, 17–22. [Google Scholar]

- White, P.J.; Broadley, M.R. Calcium in plants. Ann. Bot. 2003, 92, 487–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weng, X.; Li, H.; Ren, C.; Zhou, Y.; Zhu, W.; Zhang, S.; Liu, L. Calcium regulates growth and nutrient absorption in poplar seedlings. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 887098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaul, O. Magnesium transport and function in plants: The tip of the iceberg. Biometals 2002, 15, 307–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagliari, P.; Kaiser, D.; Rosen, C.; Lamb, J. The Nature of Phosphorus in Soils; Nutrient Management, University of Minnesota Extension: St Paul, MN, USA, 2017; FO-6795-C. [Google Scholar]

- Selvaraj, V.; Sankar, J. Characterisation of magnesium toxicity, its influence on amino acid synthesis pathway and biochemical parameters of tea. Res. J. Phytochem. 2010, 4, 67–77. [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhry, A.H.; Nayab, S.; Hussain, S.B.; Ali, M.; Pan, Z. Current understandings on magnesium deficiency and future outlooks for sustainable agriculture. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.G.; Waskom, R.M.; Bauder, T.A. Managing Sodic Soils. 2012. Available online: https://extension.colostate.edu/topic-areas/agriculture/managing-sodic-soils-0-504/ (accessed on 9 March 2023).

- Weishaar, J.L.; Aiken, G.R.; Bergamaschi, B.A.; Fram, M.S.; Fujii, R.; Mopper, K. Evaluation of specific ultraviolet absorbance as an indicator of the chemical composition and reactivity of dissolved organic carbon. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2003, 37, 4702–4708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Zhao, X.; Wu, W.; Hou, J.; Zhang, W.; Tang, D.K.H.; Zhang, X.; Yang, G.; Zhang, Z.; Yao, Y.; et al. Biotic and abiotic effects of manganese salt and apple branch biochar co-application on humification in the co-composting of hog manure and sawdust. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 482, 149077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayhew, L. Humic substances in biological agriculture. Acres 2004, 34, 54–61. [Google Scholar]

- Amlinger, F.; Peyr, S.; Geszti, J.; Dreher, P.; Karlheinz, W.; Nortcliff, S. Beneficial Effects of Compost Application on Fertility and Productivity of Soils; Federal Ministry for Agriculture and Forestry, Environment and Water Management (Lebensministerium.at): Wien, Austria, 2007; 173p. [Google Scholar]

- Roghanian, S.; Hosseini, H.M.; Savaghebi, G.; Halajian, L.; Jamei, M.; Etesami, H. Effects of composted municipal waste and its leachate on some soil chemical properties and corn plant responses. Int. J. Agric. Res. Rev. 2012, 2, 801–814. [Google Scholar]

- Hanay, A.; Büyüksönmez, F.; Kiziloglu, F.M.; Canbolat, M.Y. Reclamation of saline-sodic soils with gypsum and MSW compost. Compost. Sci. Util. 2004, 12, 175–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UC-IPM. University of California Statewide Integrated Pest Management Program (UC IPM). Nutrient and Mineral Excesses, Salinity, and Salt Toxicity. 2021. Available online: https://ipm.ucanr.edu/PMG/GARDEN/ENVIRON/salttoxicity.html (accessed on 9 March 2023).

- Cogger, C.G. Potential compost benefits for restoration of soils disturbed by urban development. Compost. Sci. Util. 2005, 13, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, S.; Mondal, R. Effect of amendments and saline irrigation water on soil properties and yields of rice and wheat in a highly sodic soil. J. Agric. Sci. 1994, 122, 351–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giusquiani, P.; Pagliai, M.; Gigliotti, G.; Businelli, D.; Benetti, A. Urban Waste Compost: Effects on Physical, Chemical, and Biochemical Soil Properties; American Society of Agronomy, Crop Science Society of America, and Soil Science Society of America: Madison, WI, USA, 1995; Volume 24, pp. 175–182. [Google Scholar]

- Schulz, H.; Dunst, G.; Glaser, B. Positive effects of composted biochar on plant growth and soil fertility. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2013, 33, 817–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.; Su, X.; Jiang, X.; Yao, W.; Chen, S.; Yang, Q.; Ning, S. Irrigation salinity affects water infiltration and hydraulic parameters of red soil. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Irrigation Water | pH | EC | TDS | Alkalinity | SAR | Na+ | Ca2+ | Mg2+ | K+ | Cl− | NO3− | SO42− |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (mS/cm) | (mg/L) | (mg/L as CaCO3) | (mg/L) | |||||||||

| Brackish water | 8.05 | 2.010 | 1088 | 290 | 9.0 | 307 | 61.9 | 15.7 | 2.2 | 29.3 | 0.5 | 664 |

| Agricultural water | 7.08 | 0.792 | 413 | 160 | 6.4 | 130 | 21.8 | 5.5 | 5.3 | 16.9 | 0.24 | 233 |

| Irrigation Water Type | Soil Treatment | Plant | Soil Electrical Conductivity (mS/cm) | Soil Moisture Content (m3/m3) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–15 cm | 15–30 cm | 30–45 cm | 0–15 cm | 15–30 cm | 30–45 cm | |||

| Brackish water | No compost | No plant | 3.000 ± 0.554 ab | 2.401 ± 0.235 d | 2.557 ± 0.280 d | 0.252 ± 0.037 a | 0.237 ± 0.012 b | 0.245 ± 0.012 c |

| Brackish water | Compost | No plant | 2.752 ± 0.505 b | 2.942 ± 0.287 b | 3.541 ± 0.399 ab | 0.242 ± 0.019 abc | 0.246 ± 0.014 a | 0.300 ± 0.014 a |

| Brackish water | No compost | Plant | 2.930 ± 0.597 ab | 2.756 ± 0.296 bc | 3.063 ± 0.336 c | 0.231 ± 0.015 bc | 0.222 ± 0.014 d | 0.275 ± 0.021 b |

| Brackish water | Compost | Plant | 3.058 ± 0.350 a | 3.666 ± 0.364 a | 3.668 ± 0.498 a | 0.230 ± 0.013 c | 0.224 ± 0.009 d | 0.280 ± 0.016 b |

| Agricultural water | No compost | No plant | 2.249 ± 0.243 c | 2.090 ± 0.388 e | 2.245 ± 0.376 e | 0.252 ± 0.023 a | 0.248 ± 0.011 a | 0.257 ± 0.023 c |

| Agricultural water | Compost | No plant | 2.076 ± 0.267 c | 2.430 ± 0.414 d | 3.209 ± 0.650 c | 0.244 ± 0.024 abc | 0.253 ± 0.008 a | 0.300 ± 0.016 a |

| Agricultural water | No compost | Plant | 2.112 ± 0.384 c | 1.852 ± 0.123 f | 2.167 ± 0.203 e | 0.246 ± 0.027 ab | 0.234 ± 0.015 bc | 0.271 ± 0.024 b |

| Agricultural water | Compost | Plant | 2.277 ± 0.301 c | 2.670 ± 0.298 c | 3.320 ± 0.497 bc | 0.230 ± 0.015 c | 0.228 ± 0.008 cd | 0.283 ± 0.028 a |

| p-value | C | 0.001 | 0.094 | 0.501 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| P | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.115 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.452 | ||

| IW | 0.083 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.200 | ||

| CxP | 0.965 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.312 | 0.000 | ||

| CxIW | 0.161 | 0.016 | 0.552 | 0.039 | 0.006 | 0.457 | ||

| IWxP | 0.212 | 0.746 | 0.366 | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.145 | ||

| CxIWxP | 0.126 | 0.315 | 0.847 | 0.449 | 0.003 | 0.048 | ||

| Irrigation Water | Soil Treatment | Plant | Total Mass of Leaching (mg) | SAR in 6 Days (Before Planting) | SAR after 56 Days of Irrigation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NO3− | Cl− | Na+ | Ca2+ | Mg2+ | K+ | DOC | |||||

| Brackish water | No compost | No plant | 1012 ± 34 ab | 604 ± 11 a | 991 ± 37 ab | 952 ± 24 abc | 248 ± 12 bc | 37 ± 4 bcd | 133 ± 15 b | 1.8 ± 0.1 a | 4.4 ± 0.2 b |

| Brackish water | No compost | Plant | 996 ± 110 abc | 488 ± 42 ab | 694 ± 64 bc | 1206 ± 114 a | 392 ± 16 a | 40 ± 3 bc | 80 ± 1 cd | 1.9 ± 0.1 a | 3.3 ± 0.2 c |

| Brackish water | Compost | No plant | 570 ± 50 d | 562 ± 39 ab | 1114 ± 92 a | 1293 ± 53 a | 309 ± 16 b | 65 ± 4 a | 248 ± 13 a | 1.8 ± 0.1 a | 4.2 ± 0.3 b |

| Brackish water | Compost | Plant | 759 ± 7 cd | 426 ± 80 ab | 855 ± 133 ab | 999 ± 133 ab | 152 ± 19 d | 20 ± 2 f | 72 ± 16 d | 2.0 ± 0.0 a | 5.6 ± 0.2 a |

| Agricultural water | No compost | No plant | 1078 ± 155 a | 525 ± 31 ab | 524 ± 33 cd | 717 ± 22 bc | 219 ± 13 cd | 34 ± 1 cde | 121 ± 14 bc | 1.7 ± 0.0 a | 2.6 ± 0.2 d |

| Agricultural water | No compost | Plant | 804 ± 124 bcd | 494 ± 49 ab | 345 ± 23 d | 696 ± 53 bc | 222 ± 21 cd | 24 ± 2 ef | 84 ± 5 cd | 2.0 ± 0.1 a | 2.2 ± 0.1 de |

| Agricultural water | Compost | No plant | 910 ± 78 abc | 553 ± 20 ab | 504 ± 15 cd | 826 ± 26 bc | 229 ± 4 c | 47 ± 2 b | 245 ± 15 a | 2.0 ± 0.1 a | 2.1 ± 0.1 e |

| Agricultural water | Compost | Plant | 593 ± 33 d | 448 ± 44 ab | 391 ± 61 d | 623 ± 29 c | 197 ± 10 cd | 27 ± 2 def | 118 ± 8 bcd | 1.7 ± 0.1 a | 3.3 ± 0.2 c |

| p-value | C | 0.000 | 0.207 | 0.323 | 0.402 | 0.000 | 0.004 | 0.000 | 0.768 | 0.000 | |

| P | 0.010 | 0.002 | 0.000 | 0.200 | 0.322 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.214 | 0.003 | ||

| IW | 0.740 | 0.739 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.348 | 0.926 | 0.000 | ||

| CxP | 0.275 | 0.309 | 0.867 | 0.002 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.156 | 0.000 | ||

| CxIW | 0.054 | 0.336 | 0.482 | 0.627 | 0.001 | 0.249 | 0.116 | 0.898 | 0.000 | ||

| IWxP | 0.000 | 0.228 | 0.036 | 0.365 | 0.687 | 0.108 | 0.034 | 0.187 | 0.188 | ||

| CxIWxP | 0.103 | 0.771 | 0.368 | 0.082 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.378 | 0.085 | 0.012 | ||

| Irrigation Water | Soil Treatment | Plant | Organic Matter (%) | Increase OM from Raw Soil (%) | Organic Carbon (%) | Increase OC from Raw Soil (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brackish water | No compost | No plant | 15.1 ± 0.1 b | −7.9 | 3.9 ± 0.1 b | −15.5 * |

| Brackish water | Compost | No plant | 22.5 ± 0.6 a | 29.4 | 8.2 ± 0.3 a | 43.3 |

| Brackish water | No compost | Plant | 15.5 ± 0.6 b | −5 | 4.1 ± 0.1 b | −12.1 * |

| Brackish water | Compost | Plant | 22.9 ± 1.3 a | 32.1 | 8.4 ± 0.6 a | 47.3 |

| Agricultural water | No compost | No plant | 15.5 ± 0.8 b | −5.0 * | 3.9 ± 0.3 b | −15.6 * |

| Agricultural water | Compost | No plant | 22.3 ± 2.1 a | 28.5 | 7.6 ± 1.0 a | 32.7 |

| Agricultural water | No compost | Plant | 15.8 ± 1.2 b | −3.4 * | 4.1 ± 0.5 b | −12.1 * |

| Agricultural water | Compost | Plant | 22.2 ± 1.5 a | 27.7 | 7.4 ± 0.4 a | 30.2 |

| p-value | C | 0.000 | 0.000 | |||

| P | 0.592 | 0.682 | ||||

| CxP | 0.840 | 0.814 | ||||

| CxIW | 0.405 | 0.126 | ||||

| CxIWxP | 0.840 | 0.702 | ||||

| Irrigation Water | Soil Treatment | Plant | Total Mass of NO3− Irrigated (mg) | Total Mass of NO3− Leached Water (mg) | Total Mass of NO3− Leached from Soil (mg) | Leaching Reduction by Compost (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Impact of compost on NO3− leaching reduction for brackish water irrigation | ||||||

| Brackish water | No compost | No plant | 3.6 | 975 | 971.0 | |

| Brackish water | Compost | No plant | 3.6 | 581 | 577.9 | 40.5 |

| Brackish water | No compost | Plant | 3.6 | 994 | 990.0 | |

| Brackish water | Compost | Plant | 3.6 | 760 | 756.7 | 23.6 |

| Impact of compost on NO3− leaching reduction for agricultural water irrigation | ||||||

| Agricultural water | No compost | No plant | 1.8 | 1078 | 1076.5 | |

| Agricultural water | Compost | No plant | 1.8 | 906 | 903.7 | 16.1 |

| Agricultural water | No compost | Plant | 1.8 | 804 | 802.4 | |

| Agricultural water | Compost | Plant | 1.8 | 598 | 595.9 | 25.7 |

| Impact of plant on NO3− leaching reduction for brackish water irrigation | ||||||

| Brackish water | No compost | No plant | 3.6 | 975 | 970.9 | |

| Brackish water | No compost | Plant | 3.6 | 994 | 990.0 | −2.0 * |

| Brackish water | Compost | No plant | 3.6 | 581 | 577.9 | |

| Brackish water | Compost | Plant | 3.6 | 760 | 756.7 | −30.9 * |

| Impact of plant on NO3− leaching reduction for agricultural water irrigation | ||||||

| Agricultural water | No compost | No plant | 1.8 | 1078 | 1076.6 | |

| Agricultural water | No compost | Plant | 1.8 | 804 | 802.5 | 25.5 |

| Agricultural water | Compost | No plant | 1.8 | 906 | 903.8 | |

| Agricultural water | Compost | Plant | 1.8 | 598 | 595.9 | 34.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Suvendran, S.; Johnson, D.; Acevedo, M.; Smithers, B.; Xu, P. Effect of Irrigation Water Quality and Soil Compost Treatment on Salinity Management to Improve Soil Health and Plant Yield. Water 2024, 16, 1391. https://doi.org/10.3390/w16101391

Suvendran S, Johnson D, Acevedo M, Smithers B, Xu P. Effect of Irrigation Water Quality and Soil Compost Treatment on Salinity Management to Improve Soil Health and Plant Yield. Water. 2024; 16(10):1391. https://doi.org/10.3390/w16101391

Chicago/Turabian StyleSuvendran, Subanky, David Johnson, Miguel Acevedo, Breana Smithers, and Pei Xu. 2024. "Effect of Irrigation Water Quality and Soil Compost Treatment on Salinity Management to Improve Soil Health and Plant Yield" Water 16, no. 10: 1391. https://doi.org/10.3390/w16101391