Divergent Strategy in Marine Tetracyclic Meroterpenoids Synthesis

Abstract

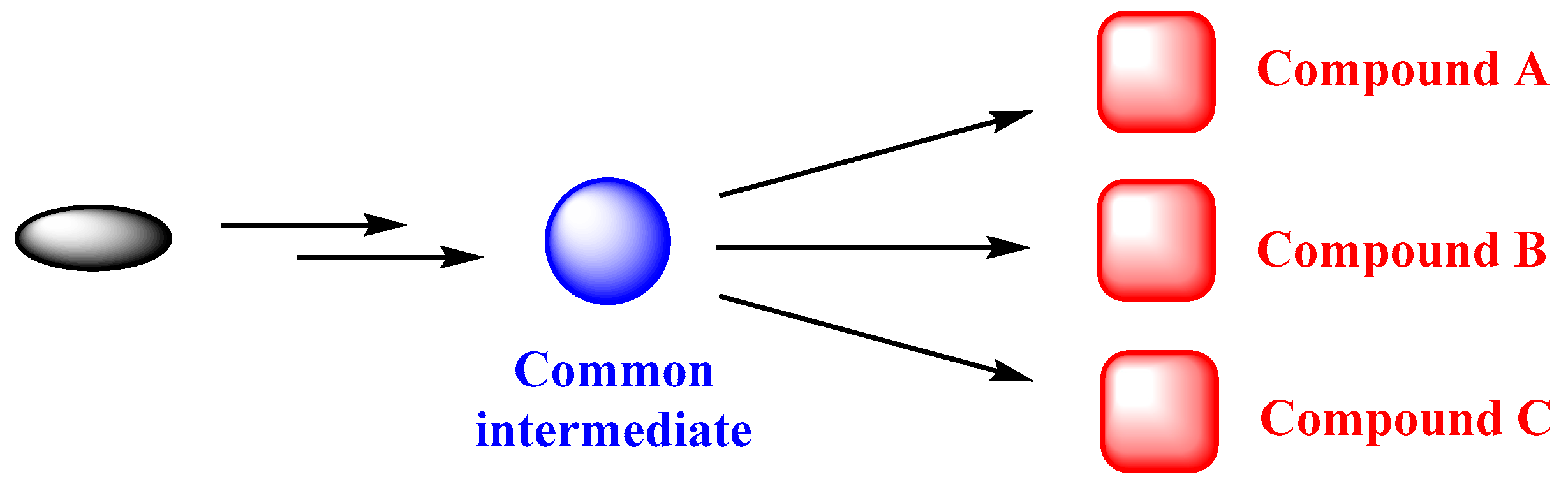

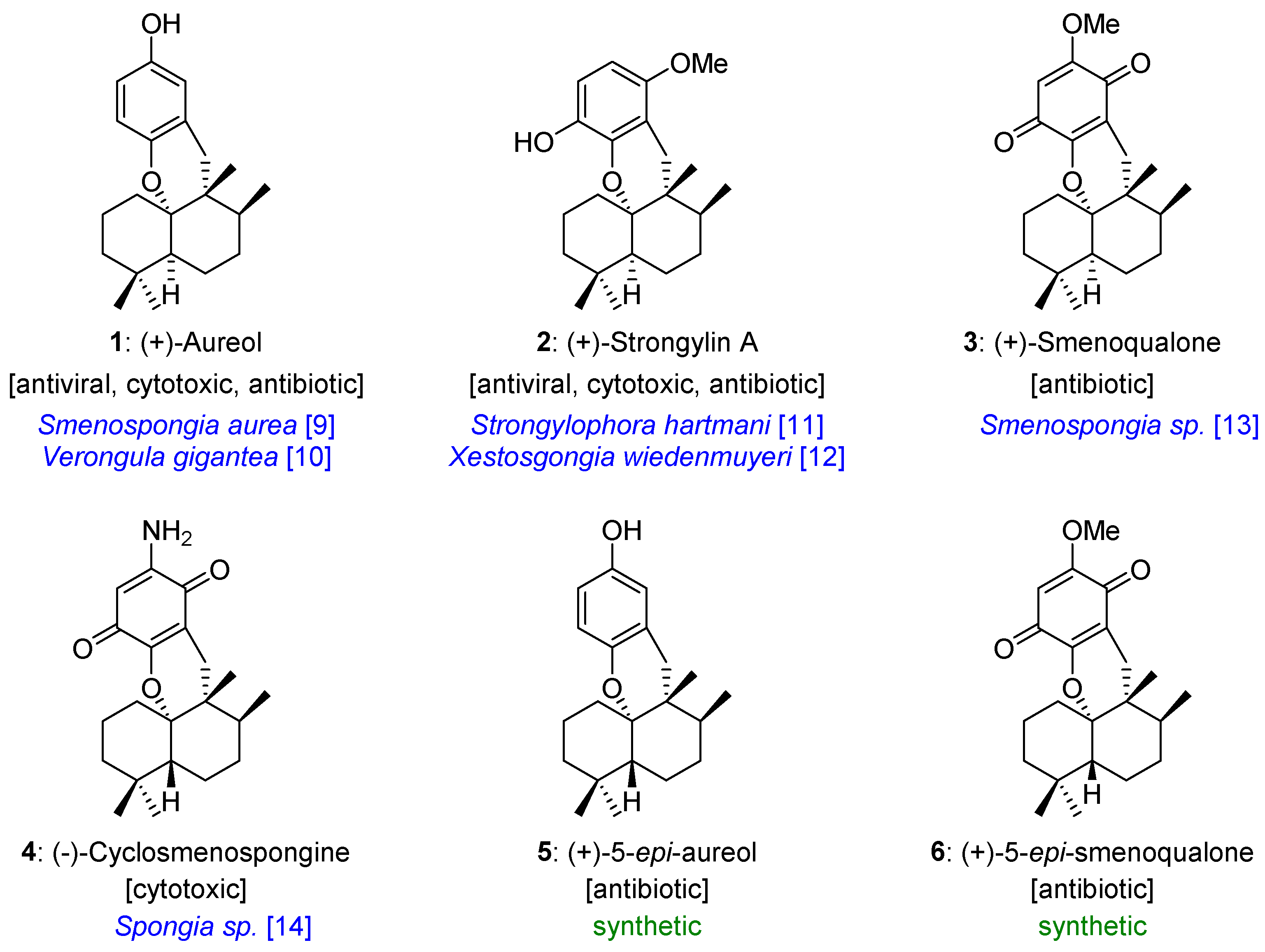

:1. Introduction

2. Synthesis of Aureol

2.1. Synthesis of Aureol from Key Intermediates 7–9

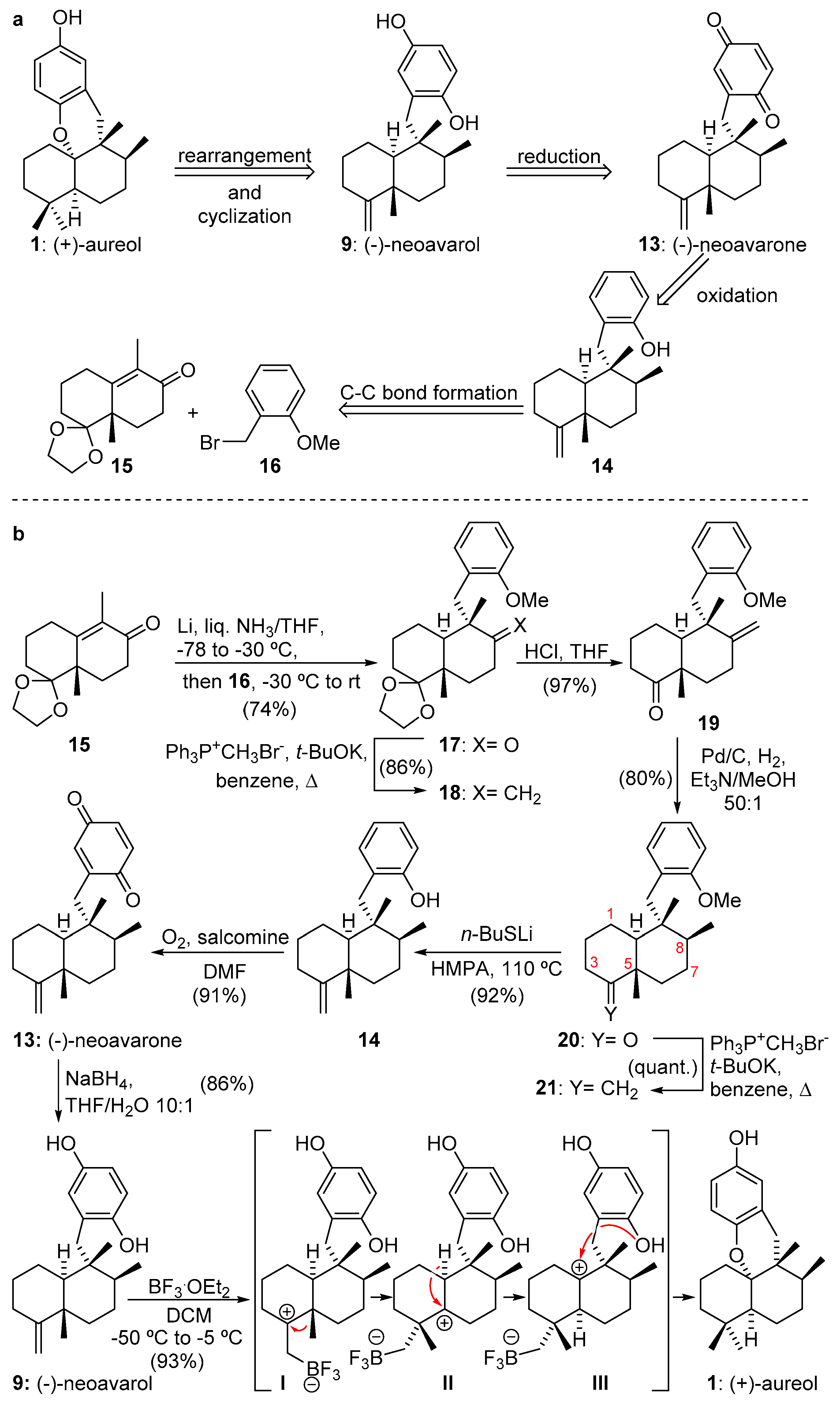

2.1.1. Capon’s Synthesis of (+)-Aureol

2.1.2. Katoh’s Synthesis of (+)-Aureol

2.2. Synthesis of Aureol from Key Intermediate 10

Magauer’s Synthesis of (+)-Aureol

2.3. Synthesis of Aureol from Key Intermediate 11

2.3.1. Marcos’s Synthesis of (−)-Aureol

2.3.2. George’s Synthesis of (+)-Aureol

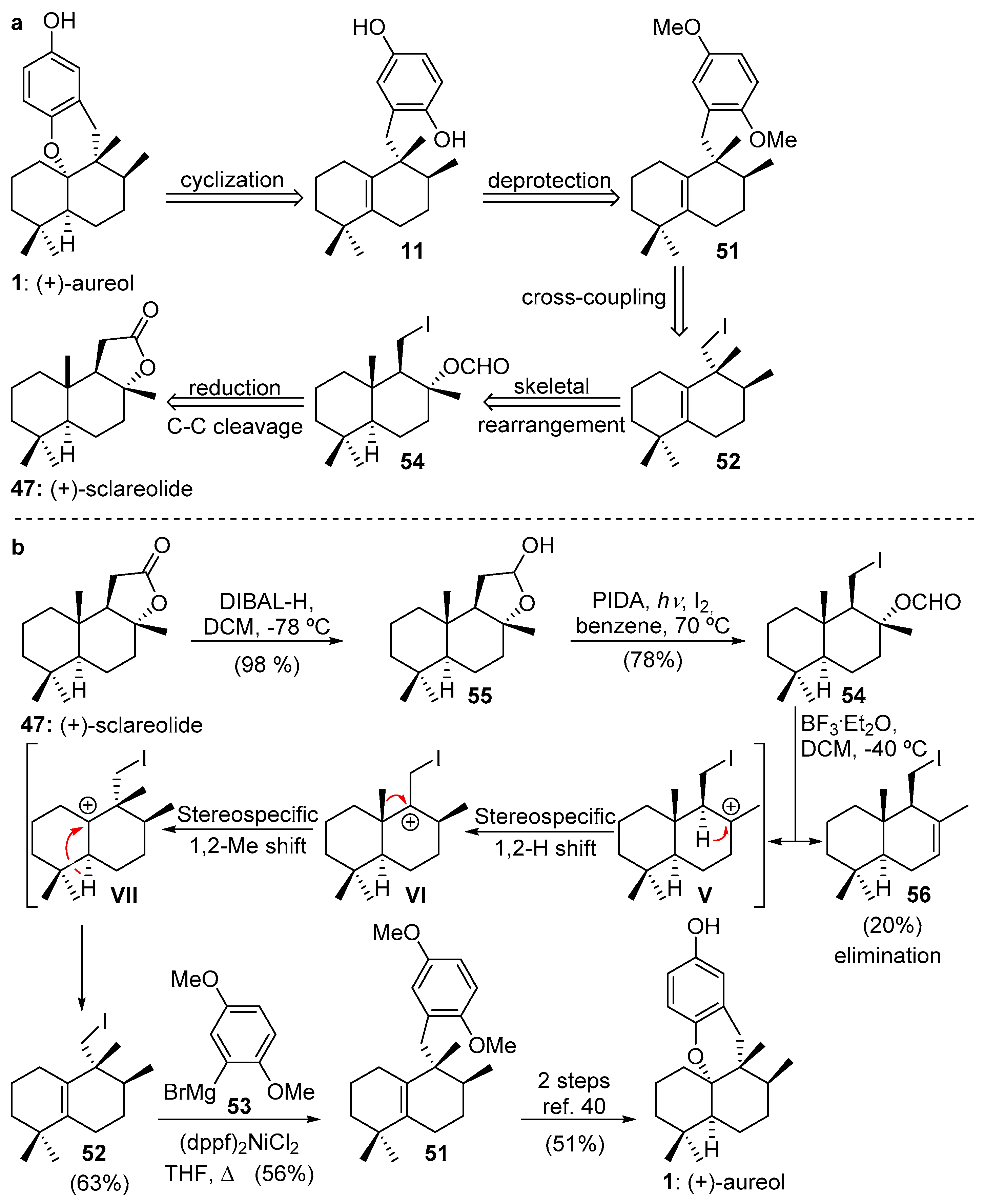

2.3.3. Wu’s Synthesis of (+)-Aureol

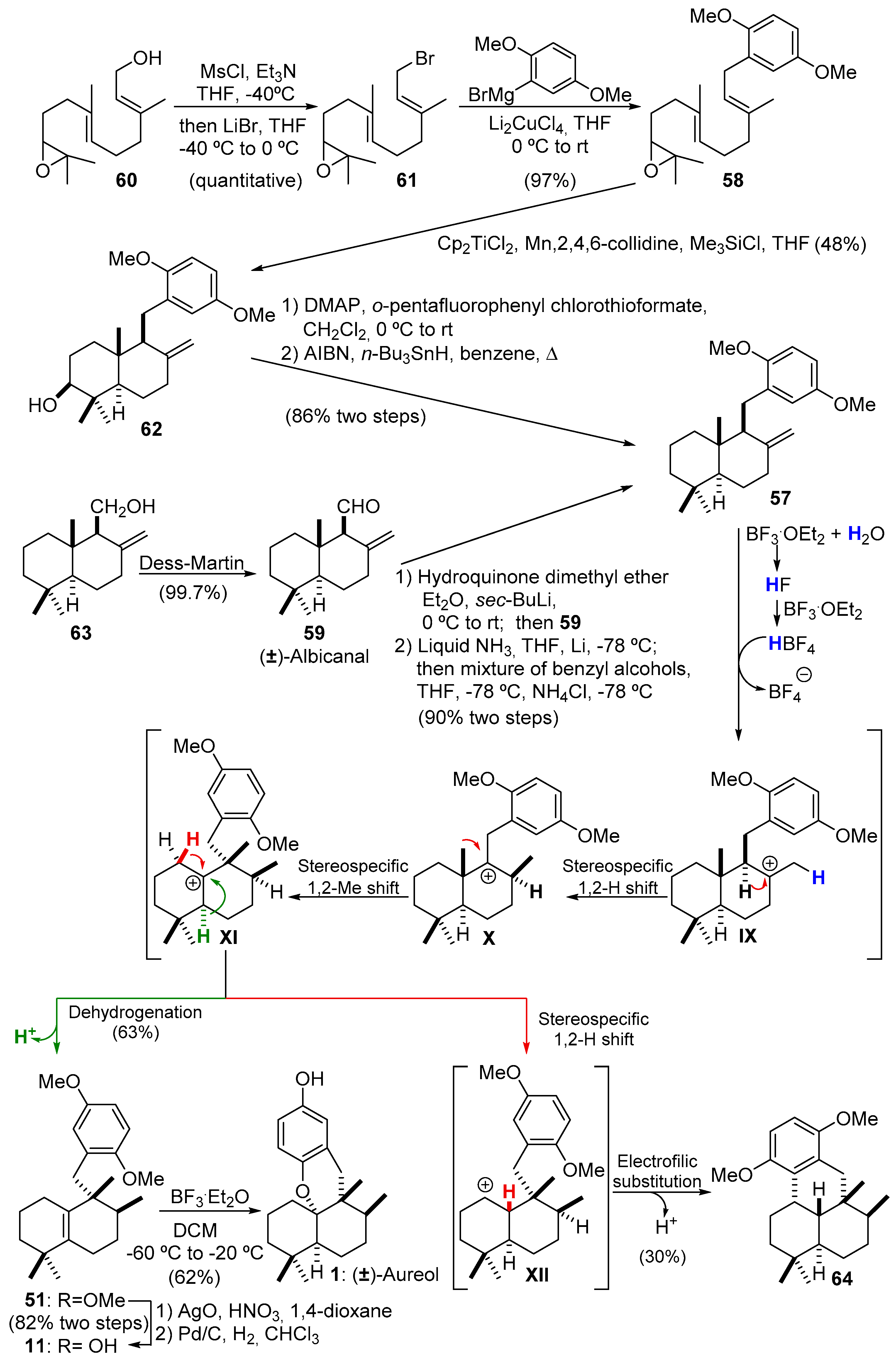

2.3.4. Rosales Martínez’s Synthesis of (±)-Aureol

3. Aureol as Pluripotent Late-Stage Intermediate for the Synthesis of Tetracyclic Meroterpenoids

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Boger, D.L.; Brotherton, C.E. Total synthesis of azafluoranthene alkaloids: Rufescine and imeluteine. J. Org. Chem. 1984, 49, 4050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, X.; Jia, Y. Divergent Strategy in Natural Product Total Synthesis. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 3752–3832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimokawa, J. Divergent strategy in natural product total synthesis. Tetrahedron Lett. 2014, 55, 6156–6162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Njardarson, J.T.; Gaul, C.; Shan, D.; Huang, X.-Y.; Danishefsky, S.J. Discovery of Potent Cell Migration Inhibitors through Total Synthesis: Lessons from Structure-Activity Studies of (+)-Migrastatin. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 1038–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S.B.; Simmons, B.; Mastracchio, A.; MacMillan, D.W.C. Collective synthesis of natural products by means of organocascade catalysis. Nature 2011, 475, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Katoh, T. Total synthesis of decahydrobenzo[d]xanthene sesquiterpenoids aureol, strongylin A, and stachyflin. Development of a new strategy for the construction of a common tetracyclic core structure. Heterocycles 2013, 87, 2199–2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, Y.; Wang, W.; Xu, T. Total synthesis of bioactive marine meroterpenoids: The cases of liphagal and frondosin B. Mar. Drugs 2018, 16, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wildermuth, R.; Speck, K.; Haut, F.-L.; Mayer, P.; Karge, B.; Broenstrup, M.; Magauer, T. A modular synthesis of tetracyclic meroterpenoid antibiotics. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Djura, P.; Stierle, D.B.; Sullivan, B.; Faulkner, D.J.; Arnold, E.V.; Clardy, J. Some metabolites of the marine sponges Smenospongia aurea and Smenospongia (. ident. Polyfibrospongia) echina. J. Org. Chem. 1980, 45, 1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciminiello, P.; Dell’Aversano, C.; Fattorusso, E.; Magno, S.; Pansini, M. Chemistry of Verongida sponges. 10. Secondary metabolite composition of the Caribbean sponge Verongula gigantea. J. Nat. Prod. 2000, 63, 263–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, A.E.; Rueth, S.A.; Cross, S.S. An antiviral sesquiterpene hydroquinone from the marine sponge Strongylophora hartmani. J. Nat. Prod. 1991, 54, 1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coval, S.J.; Conover, M.A.; Mierzwa, R.; King, A.; Puar, M.S.; Phife, D.W.; Pai, J.-K.; Burrier, R.E.; Ahn, H.-S.; Boykow, G.C.; et al. Wiedendiol-A and -B, cholesteryl ester transfer protein inhibitors from the marine sponge Xestospongia wiedenmayeri. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1995, 5, 605–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourguet-Kondracki, M.L.; Martin, M.T.; Guyot, M. Smenoqualone, a novel sesquiterpenoid from the marine sponge Smenospongia sp. Tetrahedron Lett. 1992, 33, 8079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utkina, N.K.; Denisenko, V.A.; Scholokova, O.V.; Makarchenko, A.E. Determination of the Absolute Stereochemistry of Cyclosmenospongine. J. Nat. Prod. 2003, 66, 1263–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urban, S.; Capon, R.J. Marine sesquiterpene quinones and hydroquinones: Acid-catalyzed rearrangements and stereochemical investigations. Aust. J. Chem. 1994, 47, 1023–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speck, K.; Wildermuth, R.; Magauer, T. Convergent Assembly of the Tetracyclic Meroterpenoid (-)-Cyclosmenospongine by a Non-Biomimetic Polyene Cyclization. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 14131–14135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Speck, K.; Magauer, T. Evolution of a Polyene Cyclization Cascade for the Total Synthesis of (-)-Cyclosmenospongine. Chem. Eur. J. 2017, 23, 1157–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prokof’eva, N.G.; Utkina, N.K.; Chaikina, E.L.; Makarchenko, A.E. Biological activities of marine sesquiterpenoid quinones: Structure-activity relationships in cytotoxic and hemolytic assays. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2004, 139B, 169–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, A.E.; Cross, S.S.; Burres, N.S.; Koehn, F. Antiviral and Antitumor Terpene Hydroquinones from Marine Sponge and Methods of Use. U.S. Patent WO9,112,250, 22 August 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Longley, R.E.; McConnell, O.J.; Essich, E.; Harmody, D. Evaluation of marine sponge metabolites for cytotoxicity and signal transduction activity. J. Nat. Prod. 1993, 56, 915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakshmi, V.; Gunasekera, S.P.; Schmitz, F.J.; Ji, X.; Van der Helm, D. Acid-catalyzed rearrangement of arenerol. J. Org. Chem. 1990, 55, 4709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, M.; Suzuki, A.; Nakatani, M.; Fuchikami, T.; Inoue, M.; Katoh, T. An efficient synthesis of (+)-aureol via boron trifluoride etherate-promoted rearrangement of (+)-arenarol. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002, 43, 6929–6932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, A.; Nakatani, M.; Nakamura, M.; Kawaguchi, K.; Inoue, M.; Katoh, T. Highly improved synthesis of (+)-aureol via (-)-neoavarone and (-)-neoavarol, by employing salcomine oxidation and acid-induced rearrangement/cyclization strategy. Synlett 2003, 329–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakurai, J.; Oguchi, T.; Watanabe, K.; Abe, H.; Kanno, S.-I.; Ishikawa, M.; Katoh, T. Highly efficient total synthesis of the marine natural products (+)-avarone, (+)-avarol, (-)-neoavarone, (-)-neoavarol and (+)-aureol. Chem. Eur. J. 2008, 14, 829–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukuyama, T.; Lin, S.C.; Li, L. Facile reduction of ethyl thiol esters to aldehydes: Application to a total synthesis of (+)-neothramycin A methyl ether. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990, 112, 7050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, T.; Danishefsky, S.J.; de Gala, S. A Concise Total Synthesis of (±)-Mamanuthaquinone by Using an exo-Diels–Alder Reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1994, 33, 853–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buter, J.; Heijnen, D.; Wan, I.C.; Bickelhaupt, F.M.; Young, D.C.; Otten, E.; Moody, D.B.; Minnaard, A.J. Stereoselective Synthesis of 1-Tuberculosinyl Adenosine; a Virulence Factor of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 81, 6686–6696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcos, I.S.; Conde, A.; Moro, R.F.; Basabe, P.; Díez, D.; Urones, J.G. Synthesis of quinone/hydroquinone sesquiterpenes. Tetrahedron 2010, 66, 8280–8290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcos, I.S.; Hernández, F.A.; Sexmero, M.J.; Díez, D.; Basabe, P.; Pedrero, A.B.; García, N.; Sanz, F.; Urones, J.G. Synthesis and absolute configuration of (-)-chettaphanin II. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002, 43, 1243–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcos, I.S.; Hernández, F.A.; Sexmero, M.J.; Díez, D.; Basabe, P.; Pedrero, A.B.; García, N.; Urones, J.G. Synthesis and absolute configuration of (-)-chettaphanin I and (-)-chettaphanin II. Tetrahedron 2003, 59, 685–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, T.; Poupon, E.; Rueden, E.J.; Kim, S.H.; Theodorakis, E.A. Unified Synthesis of Quinone Sesquiterpenes Based on a Radical Decarboxylation and Quinone Addition Reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 12261–12267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, T.; Xiang, A.X.; Theodorakis, E.A. Enantioselective total synthesis of avarol and avarone. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1999, 38, 3089–3091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuan, K.K.W.; Pepper, H.P.; Bloch, W.M.; George, J.H. Total Synthesis of (+)-Aureol. Org. Lett. 2012, 14, 4710–4713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharpless, K.B.; Young, M.W. Olefin synthesis. Rate enhancement of the elimination of alkyl aryl selenoxides by electron-withdrawing substituents. J. Org. Chem. 1975, 40, 947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majetich, G.; Grieco, P.A.; Nishizawa, M. Total synthesis of β-elemenone. J. Org. Chem. 1977, 42, 2327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.-L.; Li, H.-J.; Wang, M.; Wang, J.-H.; Wu, Y.-C. A six-step synthetic approach to marine natural product (+)-aureol. Tetrahedron Lett. 2018, 59, 945–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Concepción, J.I.; Francisco, C.G.; Freire, R.; Hernández, R.; Salazar, J.A.; Suárez, E. Iodosobenzene diacetate, an efficient reagent for the oxidative decarboxylation of carboxylic acids. J. Org. Chem. 1986, 51, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosales, A.; Muñoz-Bascón, J.; Roldán-Molina, E.; Rivas-Bascón, N.; Padial, N.M.; Rodríguez-Maecker, R.; Rodríguez-García, I.; Oltra, J.E. Synthesis of (±)-Aureol by Bioinspired Rearrangements. J. Org. Chem. 2015, 80, 1866–1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosales Martínez, A.; Enríquez, L.; Jaraíz, M.; Pozo Morales, L.; Rodríguez-García, I.; Díaz Ojeda, E. A Concise Route for the Synthesis of Tetracyclic Meroterpenoids: (±)-Aureol Preparation and Mechanistic Interpretation. Mar. Drugs 2020, 18, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosales Martínez, A.; Pozo Morales, L.; Díaz Ojeda, E.; Castro Rodríguez, M.; Rodríguez-García, I. The Proven Versatility of Cp2TiCl. J. Org. Chem. 2021, 86, 1311–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rosales Martínez, A.; Rodríguez-García, I.; López-Martínez, J.L. Divergent Strategy in Marine Tetracyclic Meroterpenoids Synthesis. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 273. https://doi.org/10.3390/md19050273

Rosales Martínez A, Rodríguez-García I, López-Martínez JL. Divergent Strategy in Marine Tetracyclic Meroterpenoids Synthesis. Marine Drugs. 2021; 19(5):273. https://doi.org/10.3390/md19050273

Chicago/Turabian StyleRosales Martínez, Antonio, Ignacio Rodríguez-García, and Josefa L. López-Martínez. 2021. "Divergent Strategy in Marine Tetracyclic Meroterpenoids Synthesis" Marine Drugs 19, no. 5: 273. https://doi.org/10.3390/md19050273

APA StyleRosales Martínez, A., Rodríguez-García, I., & López-Martínez, J. L. (2021). Divergent Strategy in Marine Tetracyclic Meroterpenoids Synthesis. Marine Drugs, 19(5), 273. https://doi.org/10.3390/md19050273