Optimizing State Forest Institutions for Forest People: A Case Study on Social Sustainability from Tunisia

Abstract

:1. The Unsolved Sustainability Issue of “Forest People”

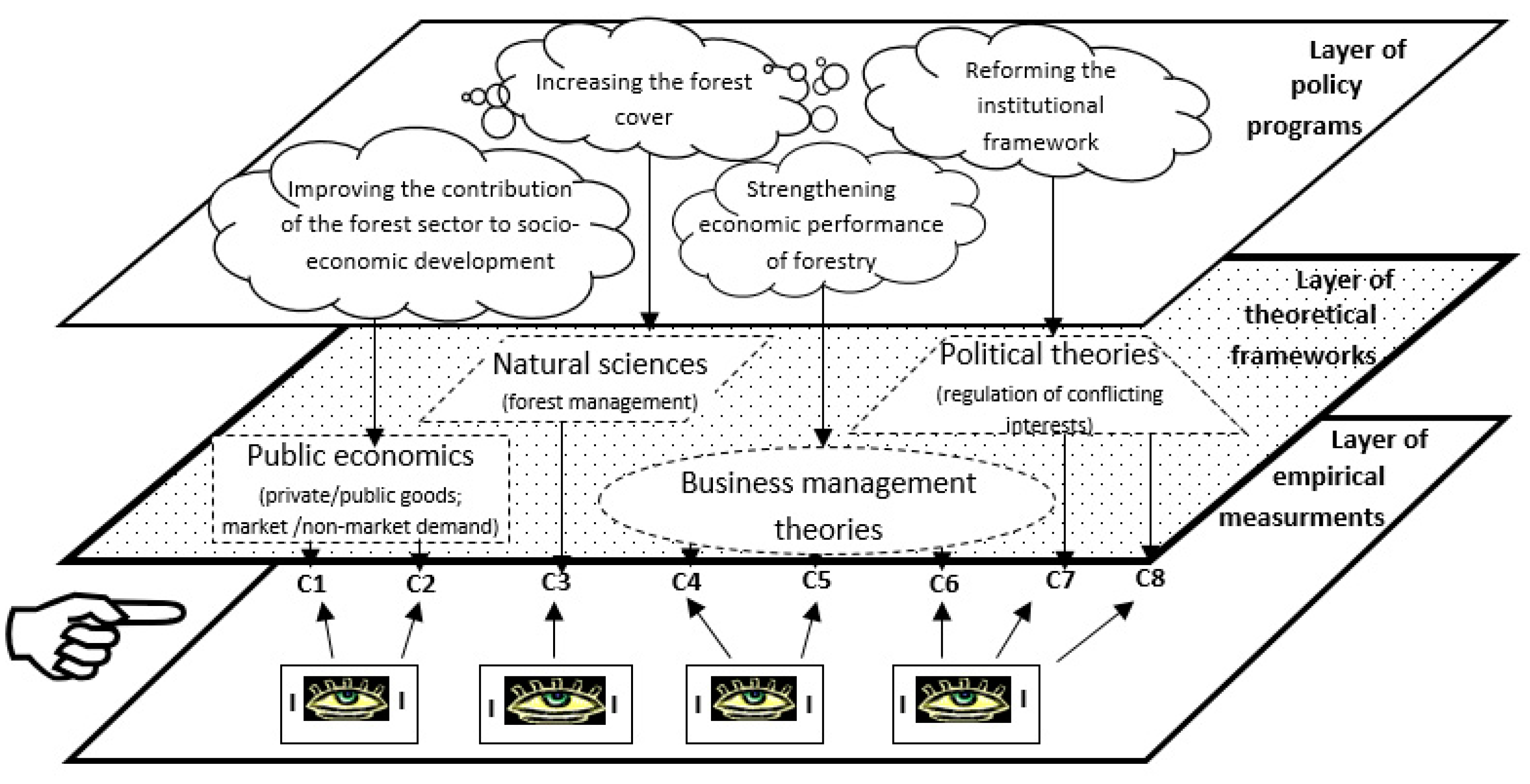

2. Comprehensive Model and Hypotheses Focused on Forest People

3. Triangulation of Multiple Empirical Methods

4. Overview of the Main Actors Involved in the Forest Policy in Tunisia

- The governmental actors: the General Directorate of Forests and its regional representations, state research institutions, the forest use authority, the Northwest Silvo-Pastoral office, different ministries (Agriculture, Tourism and Environment).

- Market actors, including wood and non-wood product industries.

- International organizations/donors who finance development projects, but also intervene in the elaboration of forest strategies and studies.

- Forest people living in and around forests who have limited legal use rights.

4.1. Insights into the Situation of Forest People in Tunisia

4.2. Relevant State Forest Institutions

4.2.1. The General Directorate of Forests and the regional institutions

4.2.2. Northwest Silvo-Pastoral Office

5. Results: Evaluation of the Performance of the Selected State Forest Institutions

5.1. The General Directorate of Forests and the regional institutions

5.1.1. Criterion 1: Orientation toward Market Demand

5.1.2. Criterion 2: Orientation toward Non-market Demand

5.1.3. Criterion 3: Sustainability of Forest Stands

5.1.4. Criterion 4: Technical Efficiency

5.1.5. Criterion 5: Profits from Forests for Forest People

5.1.6. Criterion 6: Orientation toward New Forest Goods

5.1.7. Criterion 7: Advocacy for Forestry

5.1.8. Criterion 8: Mediation of all Interests in Forests

5.2. Northwest Silvo-Pastoral Office

6. Discussion and Conclusions: Optimizing State Forest Institutions’ Performance regarding Forest People

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Tasks | State Institutions | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| National Level | Regional and Local Levels | |||

| Ministry of Agriculture | ||||

| General Directorate of Forests (DGF) | Forest Use Authority (REF) | Northwest Silvo-Pastoral Office (ODESYPANO) | Forest Divisions, Districts, Subdivisions, and Units * | |

| Forest policy formulation | ||||

| Engagement in designing forest laws, orders, decrees or other mandatory and/or voluntary prescriptions other than law, contribution to designing forest strategies and action plans. | ++ | + | 0 | ++ |

| Law implementation Enforcement of forest laws, implementation control | ++ | ++ | 0 | ++ |

| Information providing | ||||

| Extension services | + | 0 | ++ | + |

| Public reporting about forests | ++ | 0 | 0 | ++ |

| Economic support | ||||

| Financial support (incentives, compensations, investment credits, donations in kind) | + | 0 | ++ | 0 |

| Technical support (conducting operations in state-owned forests, extension excluded) | ++ | + | ++ | ++ |

| Implementation and support of development projects | ++ | 0 | ++ | ++ |

| Planning | ||||

| State-wide level | ++ | 0 | 0 | + |

| Regional level planning | ++ | 0 | ++ | ++ |

| Local level | ++ | 0 | ++ | ++ |

| Representing the owner (Setting the goals; Making decisions on concessions if some; etc.) | ++ | + | 0 | ++ |

| Management of state assets (Management of real estates, lands other than forests) | ++ | 0 | 0 | + |

| Management of forests | ||||

| Producing wood products | ++ | 0 | 0 | ++ |

| Producing non-wood products | ++ | 0 | 0 | ++ |

| Wood harvesting (organizing tenders for wood sales, thinning and sanitary cutting) | 0 | ++ | 0 | + |

| Non-wood products harvesting (Cork, Pistacia lentiscus, rosemary, mushrooms, charcoal, myrtle, thyme, Aleppo pine nuts, etc.) | 0 | ++ | 0 | + |

| Infrastructure amelioration and socio-economic development (Tracks, access to drinking water, etc.) | + | + | ++ | + |

Appendix B

| Criterion (C) | Ordinal Scale | Combination of Indicators | Performance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1: Orientation toward market demand | 3 | Supporting market revenue for forest people substantial a AND Support for professional marketing competence exists | 0 | |

| 2 | Supporting market revenue for forest people substantial AND Support for professional marketing competence does not exist | |||

| 1 | Supporting market revenue for forest people not substantial AND Support for professional marketing competence exists | |||

| 0 | Market revenue for forest people does not exist AND support for professional marketing competence does not exist | |||

| C2: Orientation toward non-market demand | 3 | Plans for production/provision of public/merit goods exist AND financial inflow for public/merit goods production/provision substantial b AND auditing exists | 2 | |

| 2 | Plans for production/provision of public/merit goods exist AND financial inflow for public/merit good production/provision substantial AND no auditing | |||

| 1 | All other combinations | |||

| 0 | No plans for production/provision of public/merit goods AND financial inflow for public/merit good production/provision not substantial AND auditing exists OR not | |||

| C3: Sustainability of forest stands | 3 | alternative A Sustained forest stands on the whole area (cca. 3/3) | alternative B (Obligation to sustain forest stands exist) AND (forest management plans exist for the substantial c forest part) AND (sustained forest stand requirements fulfilled on the whole area) | 1 |

| 2 | Sustained forest stands on the greater area (cca. 2/3) | (Obligation to sustain forest stands exists OR not) AND (forest management plans exist on substantial forest part) AND (sustained forest stand requirements fulfilled on the greater area) | ||

| 1 | Sustained forest stands on the lesser area (cca. 1/3) | All other combinations | ||

| 0 | No sustained forest stands | (Obligation to sustain forest stands does not exist) AND (no forest management plans for the substantial part of the forest) AND (sustained forest stand requirements fulfilled on whole OR greater area OR lesser area OR not fulfilled) | ||

| C4: Technical efficiency | 3 | Managerial accounting exists AND technical productivity of work is higher than the average for private enterprises | 1 | |

| 2 | Managerial accounting exists AND technical productivity of work is nearly the same as for private enterprises | |||

| 1 | Managerial accounting exists OR not) AND technical productivity is lower than the average for private enterprises | |||

| 0 | Presence OR absence of managerial accounting AND zero productivity | |||

| C5: Profits from forests for forest people | 3 | Freedom of harvesting substantial d AND profit-driven reform substantial e | 1 | |

| 2 | Freedom of harvesting exists f AND profit-driven reform substantial | |||

| 1 | Freedom of harvesting exists AND profit-driven reform exist g | |||

| 0 | No freedom of harvesting AND no profit-driven reform | |||

| C6: Orientation toward new forest goods | 3 | Existence of professional market information AND investments into new forest goods substantial h AND new external partners exist | 1 | |

| 2 | All other combinations | |||

| 1 | [Existence of professional market information AND no substantial investments into new forest goods AND no new external partners] OR [Absence of professional market information AND no substantial investments into new forest goods AND new external partners exist] OR [Absence of professional market information AND investments into new forest goods substantial AND no new external partners] | |||

| 0 | Absence of professional market information AND no substantial investments into new forest goods AND no new external partners | |||

| C7: Advocacy for forestry | 3 | Trustful cooperation with actors from the wood-based sector AND advocate’s role aspired AND advocate’s role accepted | 3 | |

| 2 | Trustful cooperation with actors from the wood-based sector AND advocate’s role not aspired AND advocate’s role accepted | |||

| 1 | Trustful cooperation with actors from the wood-based sector AND advocate’s role aspired AND advocate’s role not accepted | |||

| 0 | Trustful cooperation with actors from wood-based sector AND advocate’s role not aspired AND advocate’s role not accepted | |||

| C8: Mediation between all interests in forest | 3 | Trustful cooperation with actors from different sectors AND mediator’s role aspired AND mediator’s role accepted | 0 | |

| 2 | Trustful cooperation with actors from different sectors AND mediator’s role not aspired AND mediator’s role accepted | |||

| 1 | Trustful cooperation with actors from different sectors AND mediator’s role aspired AND mediator’s role not accepted | |||

| 0 | Trustful cooperation with actors from different sectors AND mediator’s role not aspired AND mediator’s role not accepted | |||

Appendix C

| Criterion (C) | Ordinal Scale | Combination of Indicators | Performance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1: Orientation toward market demand | 3 | Supporting market revenue for forest people substantial a AND Support for professional marketing competence exists | 0 | |

| 2 | Supporting market revenue for forest people substantial AND Support for professional marketing competence does not exist | |||

| 1 | Supporting market revenue for forest people not substantial AND Support for professional marketing competence exists | |||

| 0 | Supporting market revenue for forest people not substantial AND Support for professional marketing competence does not exist | |||

| C2: Orientation toward non-market demand | 3 | Plans for production/provision of public/merit goods exist AND financial inflow for public/merit goods production/provision substantial b AND auditing exists | 2,5 | |

| 2 | Plans for production/provision of public/merit goods exist AND financial inflow for public/merit goods production/provision substantial AND no auditing | |||

| 1 | All other combinations | |||

| 0 | No plans for production/provision of public/merit goods AND financial inflow for public/merit goods production/provision not substantial AND (auditing exists OR not) | |||

| C3: Sustainability of forest stands | 3 | alternative A Sustained forest stands on the whole area (cca. 3/3) | alternative B (Obligation to sustain forest stands exist) AND (forest management plans exist for the substantial c forest part) AND (sustained forest stand requirements fulfilled on the whole area) | 1 |

| 2 | Sustained forest stands on the greater area (cca. 2/3) | (Obligation to sustain forest stands exists OR not) AND (forest management plans exist on substantial forest part) AND (sustained forest stand requirements fulfilled on the greater area) | ||

| 1 | Sustained forest stands on the lesser area (cca. 1/3) | All other combinations | ||

| 0 | No sustained forest stands | (Obligation to sustain forest stands does not exist) AND (no forest management plans for the substantial part of the forest) AND (sustained forest stand requirements fulfilled on whole OR greater area OR lesser area OR not fulfilled) | ||

| C4: Technical efficiency | 3 | Managerial accounting exists AND Support for new technology and high productivity high d | 1 | |

| 2 | (Managerial accounting exists OR not) AND Support for new technology and high productivity moderate | |||

| 1 | (Managerial accounting exists OR not) AND Support for new technology and high productivity low | |||

| 0 | (Presence OR absence of managerial accounting) AND No support for new technology and high productivity | |||

| C5: Profits from forests for forest people | 3 | Revenue from forests for forest people substantial e AND integration of people in realizing activities defined by development plans/projects substantial f | 2 | |

| 2 | Revenue from forests for forest people exist AND (integration of people in realizing activities defined by development plans/projects Substantial OR exits) | |||

| 1 | (Revenue from forests for forest people exist OR not) AND integration of people in realizing activities defined by development plans/projects exits | |||

| 0 | NO revenue from forests for forest people AND no integration of people in realizing activities defined by development plans/projects | |||

| C6: Orientation toward new forest goods | 3 | Existence of professional market information AND investments into new forest goods substantial g AND new external partners exist | 0 | |

| 2 | All other combinations | |||

| 1 | [Existence of professional market information AND no substantial investments into new forest goods AND no new external partners] OR [Absence of professional market information AND no substantial investments into new forest goods AND new external partners exist] OR [Absence of professional market information AND investments into new forest goods substantial AND no new external partners] | |||

| 0 | Absence of professional market information AND no substantial investments into new forest goods AND no new external partners | |||

| C7: Advocacy for forestry | 3 | Trustful cooperation with actors from the wood-based sector AND advocate’s role aspired AND advocate’s role accepted | 0 | |

| 2 | Trustful cooperation with actors from the wood-based sector AND advocate’s role not aspired AND advocate’s role accepted | |||

| 1 | Trustful cooperation with actors from the wood-based sector AND advocate’s role aspired AND advocate’s role not accepted | |||

| 0 | Trustful cooperation with actors from wood-based sector AND advocate’s role not aspired AND advocate’s role not accepted | |||

| C8: Mediation between all interests in forest | 3 | Trustful cooperation with actors from different sectors AND integration of people in the decision-making process substantial | 1,5 | |

| 2 | Trustful cooperation with actors from different sectors AND integration of people in the decision-making process moderately substantial | |||

| 1 | Trustful cooperation with actors from different sectors AND integration of people in the decision-making process exists | |||

| 0 | Trustful cooperation with actors from different sectors AND integration of people in the decision-making process does not exist | |||

Appendix D

| Date | Interview Number | Type of Interview | Position of the Interviewee | Institution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25/05/2016 | Interview 1 | Sent via email | Responsible for silvo-pastoral development | General Directorate of Forests |

| 21/09/2016 | Interview 2 | Questionnaire | Responsible for forest protection | General Directorate of Forests |

| 21/09/2016 | Interview 3 | Face-to-face | Responsible for forest product sales | Forest Use Authority |

| 22/09/2016 | Interview 4 | Face-to-face | Responsible in the Environment department | Ministry of Environment |

| 29/09/2016 | Interview 5 | Questionnaire | Responsible for silvo-pastoral development | General Directorate of Forests |

| 29/11/2016 | Interview 6 | Sent via email | Responsible for silvo-pastoral development | General Directorate of Forests |

| 09/12/2016 | Interview 7 | Phone interview | Lecturer in forest science | Silvo-Pastoral Institute of Tabarka (Tunisia) |

| 15/12/2016 | Interview 8 | Sent via email | Responsible for silvo-pastoral development | General Directorate of Forests |

| 24/01/2017 | Interview 9 | Sent via email | Responsible for silvo-pastoral development | General Directorate of Forests |

| 30/01/2017 | Interview 10 | Sent via email | Responsible for and coordinator of projects | Northwest Silvo-Pastoral Office |

| 30/01/2017 | Interview 11 | Sent via email | Responsible for silvo-pastoral development | General Directorate of Forests |

| 01/02/2017 | Interview 12 | Sent via email | Responsible for and coordinator of projects | Northwest Silvo-Pastoral Office |

| 08/02/2017 | Interview 13 | Sent via email | Responsible for administrative and financial affairs | General Directorate of Forests |

| 10/02/2017 | Interview 14 | Phone interview | Doctoral students working on ecotourism | National Agronomic Institute of Tunisia |

| 27/02/2017 | Interview 15 | Sent via email | Responsible for silvo-pastoral development | General Directorate of Forests |

References

- Pierce Colfer, C.J. Marginalized Forest Peoples’ Perceptions of the Legitimacy of Governance: An Exploration. World Dev. 2011, 39, 2147–2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, S. Forest Peoples, Numbers Across the World; Forest Peoples programme: Moreton-in-Marsch, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sikor, T.; Stahl, J.; Enters, T.; Ribot, J.C.; Singh, N.; Sunderlin, W.D.; Wollenberg, L. REDD-plus, forest people’s rights and nested climate governance. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2010, 20, 423–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J. Afforestation and reforestation in the clean development mechanism of the Kyoto Protocol: Implications for forests and forest people. Int. J. Glob. Environ. Issues 2002, 2, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tounsi, K.; Ben Mimoun, A. Forest Population in Tunisia: Towards a National Socio-Economic Referential Framework; Direction Générale des Forêts/Ministère de l’agriculture; GIZ-Tunis: Tunis, Tunisia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- République Tunisienne. Code forestier et ses textes d’application; Imprimerie Officielle de la République Tunisienne: Tunis, Tunisia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Statistics. Monthly Bulletin of Statistics: January 2017. 2017. Available online: http://beta.ins.tn/en/publication/statistics-monthly-bulletin-january-2017 (accessed on 21 April 2017).

- Seklani, M. La Population de la Tunisie; Comité International de Coordination des Recherches Nationales de Démographie (CICRED): Paris, France, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Boussaïdi, N. Impacts of the Anthropogenic Activities on the Tunisian Cork oak Forest: A Test of Projection in the Future of an Ecosystem (Case of Cork Oak Forest of Kroumirie-Northwest of Tunisia). Ph.D. Thesis, Universite De Cartage Tunis, Tunis, Tunisia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bouju, S.; Gardin, J.; Auclair, L. La politique fait-elle pousser les arbres? Essai d’interprétation des permanences et mutations de la gestion forestière en Tunisie (1881–2016). Les Cahiers d’Outre-Mer 2016, 273, 221–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auclair, L.; Gardin, J. La gestion d’un milieu forestier: Entre intervention publique et stratégies paysannes (la Kroumirie, Tunisie). In Environnement et Sociétés Rurales en Mutation: Approches Alternatives; Picouet, M., Sghaier, M., Genin, D., Abaab, A., Guillaume, H., Elloumi, M., Eds.; IRD editions: Paris, France, 2004; pp. 291–306. [Google Scholar]

- Auclair, L.; Saidi, M.R. Charbonnage en Tunisie: Les filières informelles révélatrices de la crise du monde rural. Forêt Méditerranéenne 2002, 2, 133–148. [Google Scholar]

- Direction Générale des Forêts; Banque Mondiale. Diagnostic institutionnel et juridique de l’administration des forêts, recommandations et scénarii cible: Réformes institutionnelles et juridiques du secteur forestier; Direction Générale des Forêts; Banque Mondiale: Tunis, Tunisia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hasnaoui, A.; Krott, M. Political Drivers of Forest Management in Mediterranean Countries: A Comparative Study of Tunisia, Italy, Portugal and Turkey. J. New Sci. 2018, 14, 3366–3378. [Google Scholar]

- Krott, M.; Stevanov, M. Comprehensive comparison of State forest institutions by a causative benchmark-model. Allg. Forst Jagdztg. 2008, 179, 57–64. [Google Scholar]

- Stevanov, M.; Krott, M. Measuring the success of state forest institutions through the example of Serbia and Croatia. Int. For. Rev. 2013, 15, 368–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevanov, M.; Krott, M.; Curman, M.; Krajter Ostoić, S.; Stojanovski, V. The (new) role of public forest administration in Western Balkans: Examples from Serbia, Croatia, FYR Macedonia, and Republika Srpska. Can. J. For. Res. 2018, 48, 898–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. A General Framework for Analyzing Sustainability of Social-Ecological Systems. Science 2009, 325, 419–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chudy, R.; Stevanov, M.; Krott, M. Strategic options for state forest institutions in Poland: Evaluation by the 3L Model and ways ahead. Int. For. Rev. 2016, 18, 387–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Motta Bustamante, J.; Stevanov, M.; Krott, M.; Ferreira de Carvalho, E. Brazilian State Forest Institutions: Implementation of forestry goals evaluated by the 3L Model. Land Use Policy 2018, 79, 531–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dressler, H.W.; McDermott, M.; Schusser, C. The politics of community forestry in a global age: A critical analysis. For. Policy Econ. 2015, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuman, W.L. Social Research Methods: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches; Pearson New International: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Selmi, K.; Tissaoui, M.; Bacha, S. Results of the Second National Forest and Pastoral Inventory 2010; Republic of Tunisia: Tunis, Tunisia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- DGF. Rapport d’activités de l’année 2014; Direction Générale des Forêts: Tunis, Tunisia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- DGF. Rapport d’activités de 2015; Direction Générale des Forêts: Tunis, Tunisia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- DGF; FAO. Actualisation du Plan de développement communautaire Ordha-Khaddouma; Direction Générale des Forêts; Food and Agriculture Organization: Tunis, Tunisia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- DGF; FAO. Actualisation du plan de développement communautaire Jbel Zaghouan; Direction Générale des Forêts; Food and Agriculture Organization: Tunis, Tunisia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- DGF. Programme National d’activités pour l’année 2015; Direction Générale des Forêts: Tunis, Tunisia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- DGF. État des plans d’aménagement des forêts en Tunisie: Septembre 2016; Direction Générale des Forêts: Tunis, Tunisia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- DGF. Résultats du premier inventaire forestier national en Tunisie; Direction Générale des Forêts/Ministère de l’agriculture, République Tunisienne: Tunis, Tunisia, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- DGF. Superficies incendiées en hectare par année (2001–2015); Direction Générale des Forêts: Tunis, Tunisia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Färe, R.; Lovell, C.A.K. Measuring the technical efficiency of production. J. Econ. Theory 1978, 19, 150–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DGF. Programme National d’activités pour l’année 2011; Direction Générale des Forêts: Tunis, Tunisia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- DGF. Programme National d’activités pour l’année 2012; Direction Générale des Forêts: Tunis, Tunisia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- DGF. Programme National d’activités pour l’année 2013; Direction Générale des Forêts: Tunis, Tunisia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- DGF. Programme National d’activités pour l’année 2014; Direction Générale des Forêts: Tunis, Tunisia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- REF. Rapport annuel d’activité pour l’annnée 2014; Régie d’Exploitation Forestière: Tunis, Tunisia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- REF. Rapport annuel d’activités pour l’année 2015; Régie d’Exploitation Forestière: Tunis, Tunisia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- DGF. Exemple de convention pour la cogestion dans les forêts (Administration-Association); Direction Générale des Forêts: Tunis, Tunisia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- ODESYPANO. Manuel de procédures opérationnelles pour la mise en œuvre de la sous composante promotion des activités génératrices de revenus: (Projet PNO4); Quatrième Projet de Développement des Zones Montagneuses et Forestières du Nord-Ouest; Office de Développement Sylvo-Pastoral du Nord-Ouest: Béja, Tunisia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ring, I.; Schröter-Schlaack, C. (Eds.) Instrument Mixes for Biodiversity Policies; POLICYMIX Report; Issue No. 2/2011; Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research—UFZ: Leipzig, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Klooster, D.J. Toward Adaptive Community Forest Management: Integrating Local Forest Knowledge with Scientific Forestry. Econ. Geogr. 2002, 78, 43–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bala, P.A. The Potential Role of Local Knowledge in Community Forest Management: The Case of Kidundakiyave Miombo woodland, Tanzania. Master’s Thesis, Copenhagen University, Copenhagen, Denmark, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Do Thi, H.; Krott, M.; Böcher, M.; Juerges, N. Toward successful implementation of conservation research: A case study from Vietnam. Ambio 2018, 47, 608–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burns, S.L.; Krott, M.; Sayadyan, H.; Giessen, L. The World Bank Improving Environmental and Natural Resource Policies: Power, Deregulation, and Privatization in (Post-Soviet) Armenia. World Dev. 2017, 92, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.S.; Giessen, L. Formal and Informal Interests of Donors to Allocate Aid: Spending Patterns of USAID, GIZ, and EU Forest Development Policy in Bangladesh. World Dev. 2017, 94, 250–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DGF; PCFM. Stratégie nationale de développement et de gestion durable des forêts et parcours et plan d’action (2015–2024); Direction Générale des Forêts/Ministère de l’agriculture; projet régional Silva Mediterranea-PCFM/GIZ-Tunis: Tunis, Tunisia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- République Tunisienne. Programme d’investissement forestier en Tunisie: plan d’investissement; République Tunisienne: Tunis, Tunisia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Karsenty, A.; Ongolo, S.Y. Can “fragile states” decide to reduce their deforestation? The inappropriate use of the theory of incentives with respect to the REDD mechanism. For. Policy Econ. 2012, 18, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krott, M. Forest Policy Analysis; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- DGF. Projet de réforme du code forestier. proposition pour la modification d’articles sélectionnés; Direction Générale des Forêts: Tunis, Tunisia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Carlsson, L.; Berkes, F. Co-Management: Concepts and Methodological Implications Co-management: Concepts and methodological implications. J. Environ. Manag. 2005, 75, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maryudi, A.; Devkota, R.R.; Schusser, C.; Yufanyi, C.; Salla, M.; Aurenhammer, H.; Rotchanaphatharawit, R.; Krott, M. Back to basics: Considerations in evaluating the outcomes of community forestry. For. Policy Econ. 2012, 14, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schusser, C.; Krott, M.; Yufanyi Movuh, M.C.; Logmani, J.; Devkota, R.R.; Maryudi, A.; Salla, M.; Bach, N.D. Powerful stakeholders as drivers of community forestry—Results of an international study. For. Policy Econ. 2015, 58, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Criteria (C) | Explanation of the Criteria |

|---|---|

| Orientation toward market demand | Concerns forest goods and services that can be exchanged on the market (e.g., wood) and the market limits. |

| Orientation toward non-market demand | Relates to forest goods and services that cannot be exchanged on the market (public goods) or those which are considered as necessary to secure public welfare (merit goods) |

| Sustainability of forest stands | Refers to the policy goal of maintaining forest size and the capability to continually produce wood using forest management theories. |

| Technical efficiency | Refers to the efficiency that allows production to approach the maximum. |

| Profit from forests | Concerns the evaluation of the importance of revenue generated from forests. |

| Orientation toward new forest goods | Focuses on the orientation of institutions toward developing new sources of revenue from forests. |

| Advocacy for forestry | Relates to the role, within political processes, of forest institutions in managing the use and protection of forests. The advocacy’s role shows the focus of the institution on specific interests in forests without considering all different actors’ interests. |

| Mediation between all interests in the forest | Deals with the capability of the institution to apply forest governance. It is an opportunity for stakeholders to take part in policy processes. |

| Criteria (C) | Indicators for GDF Evaluation | Indicators for NWSPO Evaluation | Evaluation Result for GDF | Evaluation Results for NWSPO |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1 Orientation toward market demand | Supporting market revenue for forest people; Support for professional marketing competence | Supporting market revenue for forest people; Support for professional marketing competence | 0 | 0 |

| C2 Orientation toward non-market demand | Plans for production/provision of public/merit goods; financial inflow for public/merit goods production/ provision; Auditing | Plans for production/provision of public/merit goods; financial inflow for public/merit goods production/ provision; Auditing | 2 | 2.5 |

| C3 Sustainability of forest stands | Obligation to sustain forest stands; forest management plans; fulfilment of sustained forest stand requirements | Obligation to sustain forest stands; forest management plans; fulfilment of sustained forest stand requirements | 1 | 1 |

| C4 Technical efficiency | Managerial accounting; technical productivity of work | Managerial accounting; Support for new technology and high productivity | 1 | 1 |

| C5 Profits from forests for forest people | Freedom of harvesting; profit-driven reforms; | Revenue from forests for forest people; integration of people in the implementation of activities defined by development plans/projects | 1 | 2 |

| C6 Orientation toward new forest goods | Existence of professional market information; investments in new forest goods; existence of new external partners | Existence of professional market information investments in new forest goods; existence of new external partners | 1 | 0 |

| C7 Advocacy for forestry | Trustful cooperation with actors from the wood-based sector; aspiration to role of advocate; acceptance of role of advocate | Trustful cooperation with actors from the wood-based sector, aspiration to role of advocate; acceptance of role of advocate | 3 | 0 |

| C8 Mediation of all interests | Trustful cooperation with actors from different sectors; aspiration to role of mediator; acceptance of role of mediator | Trustful cooperation with actors from different sectors; integration of people in the decision-making process | 0 | 1.5 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hasnaoui, A.; Krott, M. Optimizing State Forest Institutions for Forest People: A Case Study on Social Sustainability from Tunisia. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1954. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11071954

Hasnaoui A, Krott M. Optimizing State Forest Institutions for Forest People: A Case Study on Social Sustainability from Tunisia. Sustainability. 2019; 11(7):1954. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11071954

Chicago/Turabian StyleHasnaoui, Ameni, and Max Krott. 2019. "Optimizing State Forest Institutions for Forest People: A Case Study on Social Sustainability from Tunisia" Sustainability 11, no. 7: 1954. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11071954

APA StyleHasnaoui, A., & Krott, M. (2019). Optimizing State Forest Institutions for Forest People: A Case Study on Social Sustainability from Tunisia. Sustainability, 11(7), 1954. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11071954