Teleworkability, Preferences for Telework, and Well-Being: A Systematic Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

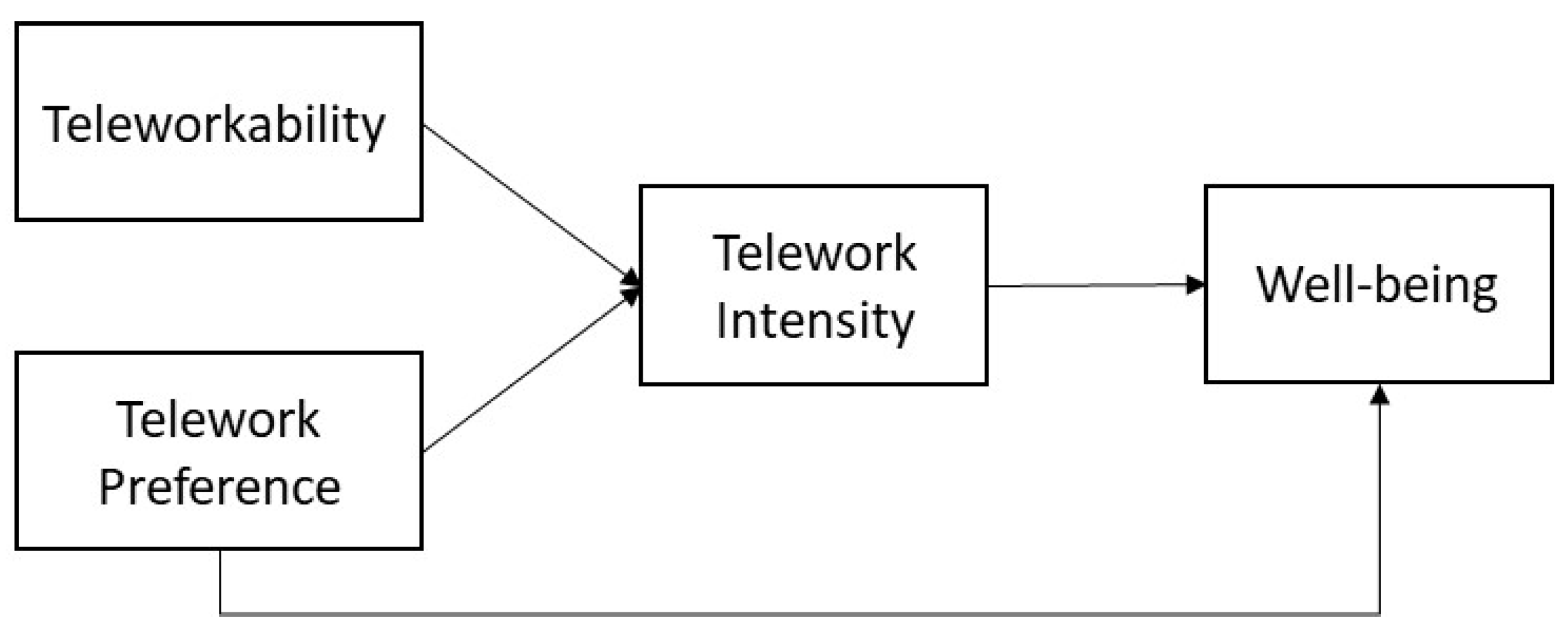

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Teleworkability and-Well-Being

2.2. Employees Telework Preference and Well-Being

2.3. Telework Intensity and Well-Being

3. Methods

4. Results

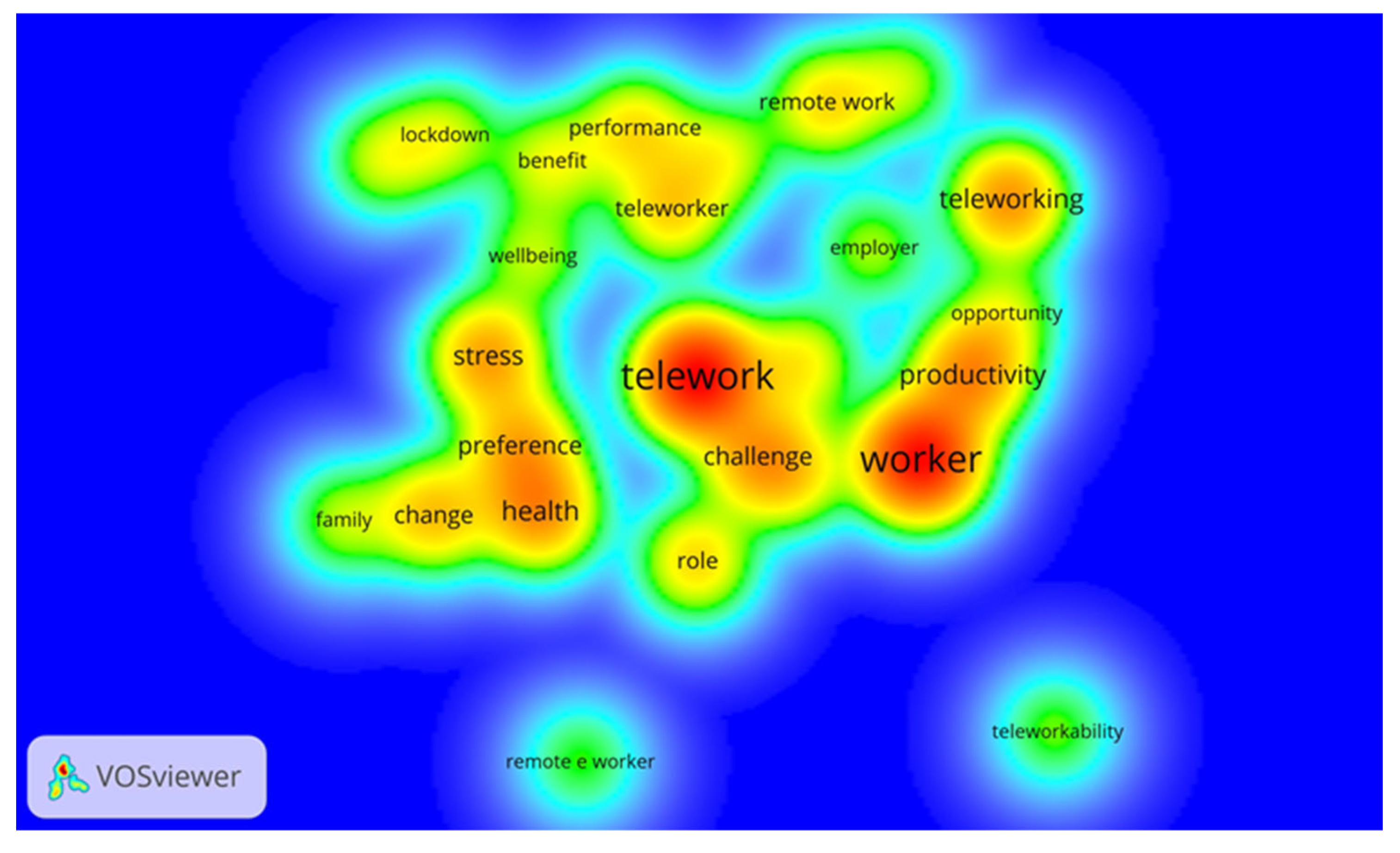

4.1. Bibliometric Results

4.2. Main Results by Variable

4.2.1. Teleworkability

4.2.2. Preference for Telework

4.2.3. Telework Intensity

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Authors | Title | Field | Study Goal | Methodology | Sample | Variables/Topics | Contributions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aczel, B.; Kovacs, M.; van der Lippe, T.; Szasz, B. 2021 [51] | Researchers working from home: Benefits and challenges | Generalistic | Whether working from home is the key or impediment to academics’ efficiency and work–life balance | Cross-sectional | N = 704 | Productivity; well-being; preference for telework | 70% of the subjects think that, in the future, they would be similarly or more efficient than before if they could spend more of their work-time at home. Regarding well-being, 66% of them would find it ideal to work from home more in the future than they did before the lockdown. |

| Adamovic, M. 2022 [72] | How does employee cultural background influence the effects of telework on job stress? The roles of power distance, individualism, and beliefs about telework | Management | Under what circumstances telework is beneficial or dysfunctional | Longitudinal | N = 604 | Job stress, cultural values, employees’ beliefs on telework effectiveness and isolation | Whether employees believe that telework negatively influence social isolation. Employees with high power distance scores have negative beliefs about telework, whereas employees with high individualism scores have positive beliefs about the effectiveness of telework. |

| Adrjan, P.; Ciminelli, G.; Judes, A.; Koelle, M.; Schwellnus, C.; Sinclair, T. 2021 [37] | Will it stay or will it go? Analysing developments in telework during COVID-19 using online job postings | International Organization | Adoption of telework across 20 countries | Quantitative. Longitudinal: 2019 to September, 2021 | 55 categories of job posted on the Indeed platform from 20 countries | Number of job positions requiring telework | Advertised telework almost tripled during the pandemic, with large differences both across sectors and across countries. The easing of restrictions only modestly reverses this increase. Digital preparedness plays an important role in mediating the response of advertised telework to changes in restrictions. |

| Alfanza, M. T. 2021 [44] | Telecommuting intensity in the context of COVID-19 pandemic: job performance and work–life balance | Economics and Business | Determining the relationship between telework intensity and employees’ work–life balance. Whether previous frameworks of WLB were still valid during the COVID-19 crisis | Cross-sectional | N = 396 | Telework intensity; job performance; work–life balance | Intensified telework had a negative relationship with employees’ WLB. No difference in the work done or the amount of time spent finishing a job at home and at the office. The WLB framework was still applicable. |

| Anderson, A. J.; Kaplan, S. A.; Vega, R. P. 2015 [49] | The impact of telework on emotional experience: When, and for whom, does telework improve daily affective well-being? | Psychology | To compare employees’ affective experience during the days that they telework and when they work at the office | Quantitative, multilevel | N = 102 US Public Services | Telework; affective well-being; individual differences | Telework improves affective well-being. Relationships between telework and positive affect are more positive for individuals higher in openness, lower in rumination, and more socially connected. |

| Arntz, M.; Ben Y. S.; Berlingieri, F. 2020 [50] | Working from home and COVID-19: The chances and risks for gender gaps | Economics and Business | Impact of telework on wages and employee availability. Develop a teleworkability index | Quantitative, longitudinal | BIBB/BauA 2018 Employment Survey, 20,000 German employees | Telework; gender | Employees without children who start teleworking do an extra hour a week of unpaid overtime, but report higher job satisfaction. |

| Babapour Chafi, C.; Hultberg, A.; and Bozic Yams, N. 2021 [66] | Post-pandemic office work: Perceived challenges and opportunities for a sustainable work environment | Economics and Business | The needs and challenges in remote and hybrid work and the potential for a sustainable future work environment | Qualitative | N = 53 Sweden. Public Services | Flexibility; autonomy; work–life balance; individual performance; lost comradery; isolation | Hybrid work provides the best of both remote and office work. To achieve the benefits of hybrid work, employers are expected to provide support and flexibility and re-design the physical and digital workplaces to fit the new and diverse needs of employees. |

| Becker, W. J.; Belkin, L. Y.; Tuskey, S. E.; Conroy, S. A.2022 [74] | Surviving remotely: How job control and loneliness during a forced shift to remote work impacted employee work behaviors and well-being | Human Resources | The impact of job control and work-related loneliness on employee work behaviors and well-being during the massive and abrupt move to remote work due to COVID-19 | Quantitative, longitudinal | 1st wave N = 334; 2nd wave N = 239 | Remote work; job control; work-related loneliness; well-being; counterproductive work behavior; depression | The beneficial impact of high perceived job control is conditioned by individual segmentation preferences such that the effects are stronger when segmentation preference is low. |

| Bérastégui, P. 2021 [38] | Teleworking in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic: enabling conditions for a successful transition | International Organization | Improve the understanding of companies and policymakers of what telework represents. | Theoretical | Telework; company culture; investment in technology; different management practices | Consensus that telework is unlikely to return to pre-pandemic levels, so it is expected to become established. | |

| Bentley, T. A., Teo, S. T., McLeod, L., Tan, F., Bosua, R., and Gloet, M. 2016 [48] | The role of organisational support in teleworker wellbeing: A socio-technical systems approach | Ergonomics | The role of organizational social support and specific support in influencing teleworker well-being. The mediating role of social isolation, and differences between low-intensity and hybrid teleworkers. | Quantitative, cross-sectional | N = 804. New Zealand | Support; psycho-logical strain; job satisfaction; social isolation; hybrid; low-intensity tele-work | Organizational social support and teleworker support increased job satisfaction and reduced psychological strain. Social isolation acts as a mediator. Differences were observed in hybrid and low-intensity teleworker sub-samples. |

| Bertoni, M.; Cavapozzi, D.; Pasini, G.; Pavese, C. 2021 [60] | Remote Working and Mental Health During the First Wave of the COVID-19 Pandemic | International Organization | To estimate the causal effect of remote working during the COVID-19 on mental health of senior Europeans. | Quantitative, longitudinal | N = 2860. 17 countries | Telework; mental health; gender; occupation; sector | Remote working increases the probability of sadness and depression. It is larger for women, respondents with children at home and singles, and in regions with low restrictions and low excess death rates due to COVID-19. |

| Biasi, P.; Checchi, D.; De Paola, M. 2022 [70] | Remote working during COVID-19 outbreak: workers’ well-being and productivity | Economics and Business | To study the multifaceted changes that represent telework | Quantitative, cross-sectional | N = 11,441. Italy | Attitude to remote work; productivity; work–life balance; gender differences | Respondents have a positive attitude towards remote work and would like to telework once the pandemic is over, especially in a hybrid model. The overlap of domestic and working spaces leaves workers, especially women, with difficulties to reconcile work and life needs. |

| Biron, M.; Turgeman-Lupo, K.; Levy, O. 2022 [77] | Integrating push–pull dynamics for understanding the association between boundary control and work outcomes in the context of mandatory work from home | Human Resources | How the constraints and benefits associated with working from home interact to shape employees’ exhaustion and goal-setting prioritization. | Quantitative, cross-sectional | N = 577. US, Israel | Working from home; boundary control; exhaustion; goal-setting/prioritization | WFH benefits (pull factors) attenuate the moderating effect of WFH constraints. |

| Brussevich, M; Dabla-Norris, D; Khalid, S. 2020 [25] | Who will Bear the Brunt of Lockdown Policies? Evidence from Tele-workability. Measures across Countries | International Organization | To present a new index of the feasibility to work from home to investigate what types of jobs are most at risk of layoffs during the lockdown | Quantitative | Occupation classification and worker-level data from 35 countries | Age; education; type of contract; company size; earnings; telework | Policies development to neutralizes differences due to demographic and distributional considerations both during the crisis and in its aftermath. |

| Camp, K. M.; Young, M.; Bushardt, S. C. 2022 [67] | A millennial manager skills model for the new remote work environment | Management | Skills model to explore millennial managers in the remote work, post-pandemic context | Theoretical | NA | Job satisfaction; productivity; commitment; work–life balance; flexibility; teamwork | The millennial manager skills model adapted to remote work in which communication, teamwork, and trust are key. |

| Charalampous, M.; Grant, C. A.; Tramontano, C. 2022 [81] | “It needs to be the right blend”: a qualitative exploration of remote e-workers’ experience and well-being at work | Human Resources | The impact of the remote e-working experience on employees’ well-being | Qualitative | 40 interviews | Affective, cognitive, social, professional, and physical well-being | Organizations should provide individuals with guidance on how to remote e-work effectively, and the importance of cultural change. |

| Charalampous, M.; Grant, C. A.; Tramontano, C. 2020 [85] | The development of the e-work well-being scale and further validation of the e-work life scale | Thesis | e-Work well-being scale | Qualitative | 63 narrative reviews, 40 interviews | Affective, cognitive, social, professional, and physical well-being | The EWW scale can be used within remote e-working populations. This scale can help academics, managers, and organizations to investigate remote e-working’s multi-dimensional impact on individuals. |

| Chambel, M. J., Castanheira, F., Santos, A.2022 [59] | Teleworking in times of COVID-19: the role of Family-Supportive supervisor behaviors in workers’ work-family management, exhaustion, and work engagement | Human Resources | Based on COR theory, the association between work–family relationships and employees’ well-being in teleworking situations was studied; specifically, the role of Family-Supportive Supervisor Behaviors (FSSB) as an important resource | Quantitative cross-sectional and longitudinal | Cross-sectional N = 318; longitudinal N = 290 | Telework; work–family relationships; FSSB; telework intensity; well-being | FSSB is related to positive outcomes for work–family relationship and well-being. Most of these relationships are influenced by telework intensity. |

| Contreras, F.; Baykal, E.; Abid, G.2020 [10] | E-leadership and teleworking in times of COVID-19 and beyond: What we know and where do we go | Psychology | In order to synthesize and move forward, this study analyzes the existing knowledge on teleworking and e-leadership, as well as the supposed challenges | Theoretical | Literature review | Telework; structure; e-leadership; productivity; well-being; environment | Telework success implies that managers must adjust the companies’ structure, making them less hierarchical, and developing new abilities to establish a strong and trustworthy relationship with their employees to maintain their competitiveness and employees’ well-being. Successful e-leadership must be able to consolidate and lead effective virtual teams to accomplish organizational goals. |

| Criscuolo, C.; Gal, P.; Leidecker, T.; Losma, F.; Nicoletti, G. 2021 [69] | The role of telework for productivity during and post-COVID-19: Results from an OECD survey among managers and workers | International Organization | Experiences and expectations about telework | Quantitative | N = 1306 managers, N = 3404 workers, 23 OECD countries | Telework; telework intensity; productivity; well-being | Managers and workers positively assess teleworking both for firm performance and for individual well-being, and wish to increase it substantially above pre-crisis levels. To increase coordination, more ICT, investment, and soft skills adapted to telework will be needed. |

| Cudanov, M.; Cvetkovié, A.; Savoiu, G. 2023 [73] | Telework Perceptions and Factors: What to Expect After the COVID-19 | Generalistic | The influence of ownership, industry, and support given by the organization to the employee | Quantitative | N = 166 | Telework benefits; telework problems; telework aversion, leaving home preferences; telework anxiousness | Public and private organizations differ on telework benefits, and between industries on telework problems. Telework is also perceived differently based on educational support. |

| de Macêdo, T.; Marques Cabral, A.; Lucas dos Santos, E; Castro, S.; Wilkson R.; de Souza Junior, C.; …; Soares, F. 2020 [52] | Ergonomics and telework: A systematic review | Prevention | To study scientific research on ergonomics and teleworking to determine the main benefits and disadvantages and to identify the main issues addressed by the authors | Systematic review | N = 36 | Teleworking; telecommuting; telecommuters; home office; ergonomics; human factors | The importance of telework for balancing professional and family life and well-being. It is necessary for companies to analyze how telework can impact on them. |

| Erro-Garcés, A.; Urien, B.; Čyras, G.; Janušauskienė V. M. 2022 [33] | Telework in Baltic Countries during the Pandemic: Effects on Wellbeing, Job Satisfaction, and Work-Life Balance | Generalistic | The direct effect of telework experience on well-being, mediated by work–life balance and job satisfaction | Quantitative, cross-sectional | N = 947, Baltic countries | Telework experience; work–life balance; job satisfaction; well-being; preference for telework | A positive experience while teleworking has a positive effect on perceived well-being, via work–life balance. In the “high preference” subsample, there is also a direct link between the experience of telework and well-being. |

| Fabrellas, A.G. 2022 [63] | How to ensure employees’ well-being in the digital age?: Discussing (new) working time policies as health and safety measures | Law and Politics | A legal analysis of working time policies in the Europe to determine their opportunity and potential to contribute to employees’ well-being in the digital age | Qualitative | NA | Flexible work; working time; well-being; Europe | The opportunity and potential for working time policies to contribute to employees’ well-being in the digital age, as they act as health and safety measures. |

| Fana, M.; Massimo, F. S.; Moro, A. 2021 [56] | Autonomy and control in mass remote working during the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from a cross-professional and cross-national analysis | International Organization | To study the effect of telework on autonomy, control, standardization, and teamwork across different occupations to highlight heterogeneity along the vertical division of labor | Qualitative | N = 50, France and Italy | Teleworkability; telework; autonomy; control; standardization; team work, division of labor | The impact of telework is not univocal and strongly depends on workers’ occupations and hierarchical positions. Economic activities and the way they have been affected by national economic lockdown also played an important role on the re-definition of actual content of tasks and their qualitative performance. |

| Gavoille, N.; Hazans, M. 2022 [75] | Personality traits, remote work and productivity, Remote Work and Productivity | International Organization | To examine the link between personality traits and workers’ productivity when working from home | Quantitative | N = 1700 | Big Five traits; willingness to telework; productivity; job satisfaction | The necessity to personalize telework in order to maximize productivity and well-being |

| Grzegorczyk, M.; Mariniello, M.; Nurski, L.; Schraepen, T. 2021 [86] | Blending the physical and virtual: a hybrid model for the future of work | International Organization | To develop a Framework Agreement on Hybrid Work in order to facilitate hybrid work context within the European single market | Qualitative Systematic Review Review | NA | Teleworkability; hybrid work; equal opportunities; minimum protection levels for on-site and hybrid workers | The need for the creation of safeguards within the work environment to protect workers’ well-being and to ensure the efficient blending of remote and on-site workers, with no differences in the way they are treated or their career opportunities. |

| Gschwind, L.; Vargas, O. 2019 [61] | Telework and its effects in Europe, Telework in the 21st Century | Economics and Business | To analyze the increase demand for flexible workplaces and working time policies at the national, sectoral, and company levels in the EU | Quantitative | Not specified. Parting from 44,000 of 2015 European Working Conditions Survey | Incidence of telework; adoption by occupation and sector; working time; work organization; work–life balance; well-being; performance; policies at various levels | The framework agreement for telework on the European Union has changed the nature of dialogue and policy-making in relation to telework. A comparison of European countries reveals how telework can develop differently depending on social and economic settings. |

| Günther, N.; Hauff, S.; Gubernator, P. 2022 [79] | The joint role of HRM and leadership for teleworker well-being: An analysis during the COVID-19 pandemic | Human Resources | To identify telework-specific HRM practices and leadership behaviors, and examine their joint relationships with teleworkers’ work engagement and job satisfaction | Quantitative, longitudinal | 1st wave, N = 601/2nd wave, N = 262 | Telework-oriented HR management; telework-oriented leadership; social isolation; psychological strain; happiness; well-being | The joint role of HRM and leadership for teleworker well-being. Telework-oriented leadership mainly affected teleworkers’ happiness and well-being via strain by ensuring communication and information exchanges between teleworkers. |

| Hu, J.; Xu, H.; Yao, Y.; Zheng, L. 2021 [65] | Is Working from Home Here, to Stay? Evidence from Job Posting Data after the COVID-19 Shock | International Organization | To examine employees’ demand toward working from home (WFH) after the COVID-19 outbreak | Quasi-experiment | N = 3,964,881 online job postings. China | Working from home; teleworkability; salaries; companies’ size; productivity; labor market inequality | A substantial increment of WFH jobs post-COVID-19 in larger firms with lower pre-COVID-19 WFH adoption. The WFH transition is clearer in jobs with higher wages and stricter requirements, which suggests that WFH will stay, inducing long-term labor market implications. |

| Iordache, A. M. M.; Dura, C. C.; Coculescu, C.; Isac, C.; Preda, A. 2021 [64] | Using Neural Networks in Order to Analyze Telework Adaptability across the European Union Countries: A Case Study of the Most Relevant Scenarios to Occur in Romania | Environment and Public Health | Telework adoption by countries in the European Union and feasible scenarios to improve telework adaptability in Romania | Quantitative, cross-sectional | N = 24,123 from living, working, and COVID-19 (round 2) | Work equipment availability; satisfaction with the experience of working from home; risk of suffering from COVID-19; employees’ openness to WFH; work–life balance; satisfaction with the work done | Disparities in telework adaptability, depending on the country level of digitalization of their economy. For example, low to moderate: Greece and Spain; fair levels: France and Hungary; and high levels: Sweden, Germany, and Ireland. |

| Karatuna, I.; Joensson, S.; Muhonen, T. 2022 [71] | Job Demands, Resources, and Future Considerations: Academics’ Experiences of Working from Home During the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic | Psychology | Changes in academics’ job demands and resources related to changes in working conditions during the pandemic, how these changes have affected the perceived occupational well-being of academics, and what are the academics’ expectations and concerns for future academic working practices following the pandemic | Qualitative, semi-structured interviews | N= 26 Sweden | Face-to-face communication; WFH, digital capacity; work overload; organizational–social support; flexibility | Lack of face-to-face communication, work overload, and work–home interference. The resources reported online communication options, appropriate working conditions, organizational–social support, and individual factors. They perceived negative occupational well-being. Academics’ expectations for the future included the continuation of working online, flexibility in the choice of workspace, and strengthened digital capacity. |

| Kim, T.; Mullins, L. B.; Yoon, T. 2020 [54] | Supervision of telework: A key to organizational performance | Public Administration | To empirically examine the role of supervisors in managing and motivating teleworkers in order to improve organizational performance | Quantitative | N = 9773 US Public Administration | Performance; supervision; social integration; telework policy; resources for telework; sociodemographics (e.g., gender) | Supervision which includes results-based management and trust-building improves the performance of organizations where employees telework. |

| Lodovici, M. S., Ferrari, E., Paladino, E., Pesce, F., Frecassetti, P. Aram, E. 2021 [53] | The impact of teleworking and digital work on workers and society | International Organization | To analyze recent trends in telework, how it influences on workers, employers, and society, and the challenges for policymaking | Mixed: Literature review | Online interviews N = 26 Web survey N = 156 | Telework; telework impacts on employees, employers, and society; telework policies | An overview of the main legislative and policy measures adopted at EU and national level, in order to identify possible policy actions at EU level. |

| Michinov, E.; Ruiller, C.; Chedotel, F.; Dodeler, V.; Michinov, N. 2022 [87] | Work-From-Home During COVID-19 Lockdown: When Employees’ Well-Being and Creativity Depend on Their Psychological Profiles | Psychology | To study how working at home relates to intensity, familiarity with WFH, employees’ well-being and creativity, and to what extent psychological profiles combined with preference for solitude may influence the effects of WFH | Quantitative, cross-sectional | N = 946 France | WFH intensity; WFH familiarity; loneliness; stress; job satisfaction; work engagement; creativity; Big Five traits | Employees higher in affiliative profile perceived lower stress, higher levels of job satisfaction, work engagement, and perceived themselves as more creative. Companies need to differentiate which employees need more support when teleworking. |

| Miglioretti, M.; Gragnano, A.; Margheritti, S.; Picco, E.2021 [57] | Not all telework is valuable | Psychology | To validate a questionnaire on telework quality and to assess the impact of telework on employee engagement and work–family balance | Quantitative, cross-sectional | N = 260 Italy | Telework quality (high, low, and no telework); work engagement; work–life balance | High-quality telework is defined by agility, flexibility, and virtual leadership. Engagement and work–family balance are higher among HqT. |

| Nguyen, M. H.; Armoogum, J. 2021 [76] | Perception and preference for home-based telework in the COVID-19 era: A gender-based analysis in Hanoi, Vietnam | Generalistic | To explore the factors associated with the perception and the preference for more home-based telework (HBT) for male versus female teleworkers | Quantitative, cross-sectional | N = 355 Vietnam | Preference for telework; age; children | 56% of female teleworkers compared with 45% of male counterparts had a positive perception of HBT; 63% of women desired to continue teleworking after the COVID-19 pandemic compared with 39% of men. |

| Norlander, P.; Erickson, Ch. 2022 [21] | The Role of Institutions in Job Teleworkability Before and After the COVID-19 Pandemic | International Organization | To examine various explanations for changes in the availability of telework job opportunities | Quantitative | N = 60,303,905 job level records N = 55,722,451 Firm level records | Task teleworkability; institutional teleworkability; interactions between these concepts; types of employer | Institutions have played a significant role in the availability of telework job opportunities before and after the COVID-19 pandemic, with an especially large effect of the government sector. |

| Otsuka, S.; Ishimaru, T.; Nagata, M.; Tateishi, S.; Eguchi, H.; Tsuji, M.; Ogami, A.; Matsuda, S.; Fujino, Y. 2021 [34] | A cross-sectional study of the mismatch between telecommuting preference and frequency associated with psychological distress among Japanese workers | Environment and Public Health | To analyze whether the mismatch between telework preference and its frequency is associated with psychological distress during the pandemic | Quantitative, cross-sectional | N= 33,302 Japan | Preference for telework; telework frequency; psychological distress; sociodemographics (age, sex, occupation, income, etc.) | The association between telework and psychological distress differs depending on employees’ preference; those who prefer telework reported less psychological distress. |

| Peters, P.; Batenburg, R. S. 2015 [58] | Telework adoption and formalization in organizations from a knowledge transfer perspective | Work Innovation | From a knowledge transfer perspective, this study analyses the consequences of telework on organizational knowledge transfer in order to explain variations in the adoption and formalization of telework practices | Quantitative, cross-sectional | N = 407 | Knowledge transfer; telework culture; management perception; time and place employees’ presence; output management; attitudes | It is more likely that companies adopt telework as a strategic HR tool if they have highly valued personnel, knowledge transfer risk is low, and if they anticipate higher commitment and productivity due to telework. |

| Ruiz-Caparrós, A. 2022 [18] | Factors determining teleworking before and during COVID-19: some evidence from Spain and Andalusia | Economics and Business | To analyze inequalities in access to telework, which factors determined telework in the pre-pandemic period and during the lockdown, and whether telework is related to the likelihood of suffering emotional disorders during lockdowns | Quantitative, comparative | N not specified from a national survey on ICT (Spain) and a regional study performed during the lockdown (Andalusia) | Sociodemographics (gender, age, educational attainment, and household composition); the type of knowledge acquired through ICT training; the nature of the ICT activity | ICT training is key to explaining the likelihood of telework. Some workers might experience difficulties in their transition. This could increase labor market segmentation, hindering the transition to a knowledge economy. No difference was identified between the place where one works and emotional disorders. |

| Schmitt, J. B.; Breuer, J.; Wulf, T. 2021 [88] | From cognitive overload to digital detox: Psychological implications of telework during the COVID-19 pandemic | Economics and Business | To analyze the relationships between the use of digital work tools, the feeling of cognitive overload, digital detox measures, perceived work performance, and well-being | Quantitative, cross-sectional | N = 403 Germany | Videoconferencing; text-based tools; age; children; cognitive overload; digital detox; performance; well-being (tension, demands, worries, etc.) | Text-based tools are associated with well-being. When using videoconferencing tools, the number of digital detox measures moderates the relationship between cognitive overload and the perception of work demands. |

| Somasundram, K. G.; Hackney, A.; Yung, M.; Du, B.; Oakman, J.; Nowrouzi-Kia, B.; Yazdani, A. 2022 [78] | Mental and physical health and well-being of Canadian employees who were working from home during the COVID-19 pandemic | International Organization | Due to its rapid increment during the pandemic, to understand teleworkers’ health and well-being and the possibility for WFH continuing in the future | Quantitative, longitudinal | N = 1617, 1st wave. N = 382, 2nd wave Analyzes only on 382 Canada | Sociodemographics; WFH preferences; workstation setup training; employment situation; hardware; usage of software; organizational return | Employees received more help and feedback from their colleagues and experienced a sense of community over time. All indicators improved as employees spent more time teleworking. |

| Sostero, M.; Milasi, S.; Hurley, J.; Fernandez-Macías, E.; Bisello, M. 2020 [24] | Teleworkability and the COVID-19 crisis: a new digital divide? | International Organization | To develop a conceptual analysis to identify the jobs that can be done from home and those that cannot, and on this basis quantify the fraction of employees that are in teleworkable occupations across EU countries, sectors, and socio-economic profiles | Quantitative, comparative | Not specified. Data from the EU labor force survey 2008 and 2019 | Teleworkable occupations; prevalence of telework; employment structure; work organization; regulation; management culture | Telework is skewed towards highly paid white-collar employment, but because of the pandemic, low–mid clerical workers also telework. Apart from differences on EU countries industrial and occupational structures, their differences were caused by work organization, regulation, and management culture. |

| Vayre, É.2021 [68] | Challenges in Deploying Telework: Benefits and Risks for Employees | Human Resources | To define telework and the situations it covers and to discuss both the benefits and the constraints associated with it | Theoretical | NA | Telework; organizational culture; well-being; work efficiency; participation | To prevent negative effects, a major change in managerial policies and practices, the redefinition of work efficiency, performance evaluation, and changes in employees’ representation are necessary. These cultural changes should be decided and implemented via a participative process. |

| Vayre, É.; Devif, J.; Gachet-Mauroz, T.; Morin-Messabel, Ch. 2021 [89] | Telework: What is at Stake for Health, Quality of Life at Work and Management Methods? | Human Resources | Studies telework and its impact on workload, working conditions, and health. Reports challenges of telework with day-to-day lives and gender equality. Studies of managerial culture and practices in mediated and remote work | Theoretical | NA | Telework; social cohesion; health; flexibility; autonomy; control; gender | Telework brings opportunities and risks to health and quality of life, professional equality, inclusion, and social cohesion. It challenges employees’ roles. It also encompasses heterogeneous configurations depending on how it is defined, deployed, accompanied, and regulated. It is complex to determine which effects it could have due to that complexity. |

| Vesala, H.; Tuomivaara, S. 2015 [55] | Slowing work down by teleworking periodically in rural settings? | Human Resources | To examine whether well-being changes during and after a retreat-type telework period in a rural environment | Quantitative, longitudinal | N = 46 | Psychosocial work environment (mental exhaustiveness, time pressure, goal clarity, negative feelings at work, etc.) | After the telework retreat, subjects experienced less time pressure, fewer interruptions, reduced negative feelings, less stress, and greater work satisfaction. Entrepreneurs and supervisors improved more than subordinates, but the results were more sustainable in the latter group. |

| Yamashita, S., Ishimaru, T., Nagata, T., Tateishi, S., Hino, A., Tsuji, M., …; Fujino, Y. 2022 [17] | Preference and frequency of teleworking in slinked with work functioning | Environment and Public Health | To examined whether telework preference and frequency were associated with work functioning impairments | Quantitative, cross-sectional | N = 27,036 Japan | Telework; preference for telework; telework intensity; work functioning impairments | A preference for telework was associated with work functioning impairments; the higher the preference, the greater the impairment. |

References

- Allen, T.D.; Golden, T.D.; Shockley, K.M. How Effective Is Telecommuting? Assessing the Status of Our Scientific Findings. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest 2015, 16, 40–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazekami, S. Mechanisms to improve labor productivity by performing telework. Telecommun. Policy 2020, 44, 101868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares, A.I. Telework and health effects review. Int. J. Health 2017, 3, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Konradt, U.; Hertel, G.; Schmook, R. Quality of management by objectives, task-related stressors, and non-task-related stressors as predictors of stress and job satisfaction among teleworkers. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2003, 12, 61–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, T.C.; Wilhelm, P.V.B.; Tabak, B.M. The role of non-critical business and telework propensity in international stock markets during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Int. Financ. Mark. Inst. Money 2022, 79, 101598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. EU Labour Force Survey. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=EU_labour_force_survey (accessed on 13 February 2023).

- Belzunegui-Eraso, A.; Erro-Garcés, A. Teleworking in the Context of the COVID-19 Crisis. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warr, P. Work, Unemployment, and Mental Health; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Buomprisco, G.; Ricci, S.; Perri, R.; De Sio, S. Health and Telework: New Challenges after COVID-19 Pandemic. Eur. J. Environ. Public Health 2021, 5, em0073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras, F.; Baykal, E.; Abid, G. E-leadership and teleworking in times of COVID-19 and beyond: What we know and where do we go. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 590271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A.M.; Christianson, M.K.; Price, R.H. Happiness, Health, or Relationships? Managerial Practices and Employee Well-Being Tradeoffs. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2007, 21, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gajendran, R.; Harrison, D. The good, the bad, and the unknown about telecommuting: Meta-analysis of psychological mediators and individual consequences. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 1524–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martin, B.H.; MacDonnell, R. Is telework effective for organizations? Manag. Res. Rev. 2012, 35, 602–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giménez-Nadal, J.I.; Molina, J.A.; Velilla, J. Work time and well-being for workers at home: Evidence from the American Time Use Survey. Int. J. Manpow. 2020, 41, 184–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal, M.T.; Anwar, I.; Khan, N.A.; Saleem, I. Work during COVID-19: Assessing the influence of job demands and resources on practical and psychological outcomes for employees. Asia-Pacific J. Bus. Adm. 2021, 13, 293–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouwerkerk, J.W.; Bartels, J. Is Anyone Else Feeling Completely Nonessential? Meaningful Work, Identification, Job Insecurity, and Online Organizational Behavior during a Lockdown in The Netherlands. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamashita, S.; Ishimaru, T.; Nagata, T.; Tateishi, S.; Hino, A.; Tsuji, M.; Ikegami, K.; Muramatsu, K.; Fujino, Y. Association of preference and frequency of teleworking with work functioning impairment: A nationwide cross-sectional study of Japanese full-time employees. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2022, 64, e363–e368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, A.C. Factors determining teleworking before and during COVID-19: Some evidence from Spain and Andalusia. Appl. Econ. Anal. 2022, 30, 196–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dingel, J.I.; Neiman, B. How many jobs can be done at home? J. Public Econ. 2020, 189, 104235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barac, K.; Plant, K.; Kunz, R.; Kirstein, M. Audit practice: A straightforward trade or a complex system? Int. J. Audit. 2021, 25, 797–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norlander, P.; Erickson, C. The Role of Institutions in Job Teleworkability before and after the COVID-19 Pandemic. Discussion Paper, No. 1172, Global Labor Organization (GLO). Essen. 2022. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/265054 (accessed on 14 November 2022).

- Asgari, H.; Jin, X. Toward a Comprehensive Telecommuting Analysis Framework. Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board 2015, 2496, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spilker, M.A.A. Making Telework Work: The Effect of Telecommuting Intensity on Employee Work Outcomes; ProQuest, University of Missouri-Saint Louis: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sostero, M.; Milasi, S.; Hurley, J.; Fernandez-Macías, E.; Bisello, M. Teleworkability and the COVID-19 Crisis: A New Digital Divide? JRC Working Papers Series on Labour, Education and Technology; No. 2020/05; European Commission, Joint Research Centre (JRC): Seville, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Brussevich, M.; Dabla-Norris, E.; Khalid, S. Who Will Bear the Brunt of Lockdown Policies? Evidence from Tele-workability Measures Across Countries; International Monetary Fund: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom, N.; Liang, J.; Roberts, J.; Ying, Z.J. Does Working from Home Work? Evidence from a Chinese Experiment. Q. J. Econ. 2021, 130, 165–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marks, M.A.; Mathieu, J.E.; Zaccaro, S.J. A Temporally Based Framework and Taxonomy of Team Processes. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2001, 26, 356–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, P.; Tijdens, K.G.; Wetzels, C. Employees’ opportunities, preferences, and practices in telecommuting adoption. Inf. Manag. 2004, 41, 469–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hive. Available online: https://hive.com/blog/remote-work-survey-2020-hive/ (accessed on 12 January 2023).

- GitLab. Available online: https://about.gitlab.com/resources/downloads/remote-work-report-2021.pdf/ (accessed on 12 January 2013).

- Rounds, J.B.; Tracey, T.J. From trait-and-factor to person-environment fit counseling: Theory and process. In Career Counseling: Contemporary Topics in Vocational Psychology; Walsh, W.B., Osipow, S.H., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1990; pp. 1–44. [Google Scholar]

- Longua, J.; DeHart, T.; Tennen, H.; Armeli, S. Personality moderates the interaction between positive and negative daily events predicting negative affect and stress. J. Res. Pers. 2009, 43, 547–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Erro-Garcés, A.; Urien, B.; Čyras, G.; Janušauskienė, V.M. Telework in Baltic Countries during the Pandemic: Effects on Wellbeing, Job Satisfaction, and Work-Life Balance. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otsuka, S.; Ishimaru, T.; Nagata, M.; Tateishi, S.; Eguchi, H.; Tsuji, M.; Fujino, Y. A cross-sectional study of the mismatch between telecommuting preference and frequency associated with psychological distress among Japanese workers in the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2021, 63, e636–e640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traqq.team. Available online: https://traqq.com/blog/permanent-remote-work-here-is-a-swot-analysis-to-decide-if-it-is-sustainable/ (accessed on 16 January 2023).

- Eurofound Fifth round of the Living, Working and COVID-19 e-Survey: Living in a New Era of Uncertainty; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2022.

- Adrjan, P.; Ciminelli, G.; Judes, A.; Koelle, M.; Schwellnus, C.; Sinclair, T. Will It Stay or Will it Go? Analysing Developments in Telework during COVID-19 Using Online Job Postings Data; OECD Productivity Working Papers; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bérastégui, P. Teleworking in the Aftermath of the COVID-19 Pandemic: Enabling Conditions for a Successful Transition; ETUI: Brussels, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Modroño, P.; Pesole, A.; López-Igual, P. Assessing gender inequality in digital labour platforms in Europe. Internet Policy Rev. 2022, 11, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henke, R.M.; Benevent, R.; Schulte, P.; Rinehart, C.; Crighton, K.A.; Corcoran, M. The Effects of Telecommuting Intensity on Employee Health. Am. J. Health Promot. 2016, 30, 604–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagata, T.M.; Nagata, M.M.; Ikegami, K.M.; Hino, A.M.; Tateishi, S.M.; Tsuji, M.M.; Matsuda, S.M.; Fujino, Y.M.; Mori, K.M. Intensity of Home-Based Telework and Work Engagement during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2021, 63, 907–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiden, M.; Widar, L.; Wiitavaara, B.; Boman, E. Telework in academia: Associations with health and well-being among staff. High. Educ. 2020, 81, 707–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Gao, J. Does Telework Stress Employees Out? A Study on Working at Home and Subjective Well-Being for Wage/Salary Workers. J. Happiness Stud. 2019, 21, 2649–2668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alfanza, M.T. Telecommuting Intensity in the Context of COVID-19 Pandemic: Job Performance and Work-Life Balance. Econ. Bus. 2021, 35, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorrell, S.; Gatersleben, B.; Druckman, A. The limits of energy sufficiency: A review of the evidence for rebound effects and negative spillovers from behavioural change. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2020, 64, 101439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahan, N.; Naveed, S.; Zeshan, M.; Tahir, M. How to Conduct a Systematic Review: A Narrative Literature Review. Cureus 2016, 8, e864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Adams, J.; Hillier-Brown, F.C.; Moore, H.J.; Lake, A.A.; Araujo-Soares, V.; White, M.; Summerbell, C. Searching and synthesising ‘grey literature’ and ‘grey information’ in public health: Critical reflections on three case studies. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bentley, T.; Teo, S.; McLeod, L.; Tan, F.; Bosua, R.; Gloet, M. The role of organisational support in teleworker wellbeing: A socio-technical systems approach. Appl. Ergon. 2016, 52, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, A.J.; Kaplan, S.A.; Vega, R.P. The impact of telework on emotional experience: When, and for whom, does telework improve daily affective well-being? Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2015, 24, 882–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arntz, M.; Ben Yahmed, S.; Berlingieri, F. Working from Home and COVID-19: The Chances and Risks for Gender Gaps. Intereconomics 2020, 55, 381–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aczel, B.; Kovacs, M.; van der Lippe, T.; Szaszi, B. Researchers working from home: Benefits and challenges. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0249127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Macêdo, T.A.M.; Cabral, E.L.d.S.; Silva Castro, W.R.; de Souza Junior, C.C.; da Costa Junior, J.F.; Pedrosa, F.M.; da Silva, A.B.; de Medeiros, V.R.F.; de Souza, R.P.; Cabral, M.A.L.; et al. Ergonomics and telework: A systematic review. Work 2020, 66, 777–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lodovici, M.S.; Ferrari, E.; Paladino, E.; Pesce, F.; Frecassetti, P.; Aram, E. The Impact of Teleworking and Digital Work on Workers and Society. Policy Department for Economic, Scientific and Quality of Life Policies Directorate-General for Internal Policies, EU Parlament. PE 662.904. April 2021. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2021/662904/IPOL_STU(2021)662904(ANN05)_EN.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2022).

- Kim, T.; Mullins, L.B.; Yoon, T. Supervision of Telework: A Key to Organizational Performance. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2021, 51, 263–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vesala, H.; Tuomivaara, S. Slowing work down by teleworking periodically in rural settings? Pers. Rev. 2015, 44, 511–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fana, M.M.; Sabato, F.; Moro, A. Autonomy and control in mass remote working during the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from a cross-professional and cross-national analysis. In LEM Working Paper Series, No. 2021/28; Scuola Superiore Sant’Anna, Laboratory of Economics and Management (LEM): Pisa, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Miglioretti, M.; Gragnano, A.; Margheritti, S.; Picco, E. Not All Telework is Valuable. J. Work. Organ. Psychol. 2021, 37, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, P.; Batenburg, R. Telework adoption and formalisation in organisations from a knowlegde transfer perspective. Int. J. Work Innov. 2015, 1, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambel, M.J.; Castanheira, F.; Santos, A. Teleworking in times of COVID-19: The role of Family-Supportive supervisor behaviors in workers’ work-family management, exhaustion, and work engagement. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2022, 1, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertoni, M.; Cavapozzi, D.; Pasini, G.; Pavese, C. Remote Working and Mental Health During the First Wave of the COVID-19 Pandemic. SSRN. 2015. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4111999 (accessed on 20 November 2022).

- Gschwind, L.; Vargas, O. Telework and its effects in Europe. In Telework in the 21st Century; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2019; pp. 36–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kozlowski, S.W.J.; Klein, K.J. A multilevel approach to theory and research in organizations: Contextual, temporal, and emergent processes. In Multilevel Theory, Research, and Methods in Organizations: Foundations, Extensions, and New Directions; Klein, K.J., Kozlowski, S.W.J., Eds.; Jossey-Bass: Hoboken, NY, USA, 2000; pp. 3–90. [Google Scholar]

- Fabrellas, A.G. How to Ensure Employees’ Well-Being in the Digital Age?: Discussing (new) Working Time Policies as Health and Safety Measures. IDP Rev. De Internet Derecho Y Política Rev. D’internet Dret I Política 2022, 35, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Iordache, A.M.M.; Dura, C.C.; Coculescu, C.; Isac, C.; Preda, A. Using Neural Networks in Order to Analyze Telework Adaptability across the European Union Countries: A Case Study of the Most Relevant Scenarios to Occur in Romania. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Xu, H.; Yao, Y.; Zheng, L. Is Working from Home Here to Stay? Evidence from Job Posting Data after the COVID-19 Shock. Working Paper SSRN. 2021. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers (accessed on 14 November 2022).

- Babapour Chafi, M.; Hultberg, A.; Yams, N.B. Post-Pandemic Office Work: Perceived Challenges and Opportunities for a Sustainable Work Environment. Sustainability 2022, 14, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camp, K.M.; Young, M.; Bushardt, S.C. A millennial manager skills model for the new remote work environment. Manag. Res. Rev. 2022, 45, 635–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vayre, E. Challenges in deploying telework: Benefits and risks for employees. In Digital Transformations in the Challenge of Activity and Work: Understanding and Supporting Technological Changes; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021; Volume 3, pp. 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Criscuolo, C.; Gal, P.; Leidecker, T.M.; Losma, F.; Nicoletti, G. The role of telework for productivity during and post-COVID-19: Results from an OECD survey among managers and workers; OECD: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biasi, P.; Checchi, D.; De Paola, M. Remote working during COVID-19 outbreak: Workers’ well-being and productivity. Politica Econ. J. Econ. Policy 2022, 1, 3–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatuna, I.; Jönsson, S.; Muhonen, T. Job Demands, Resources, and Future Considerations: Academics’ Experiences of Working From Home During the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 908640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamovic, M. How does employee cultural background influence the effects of telework on job stress? The roles of power distance, individualism, and beliefs about telework. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2021, 62, 102437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čudanov, M.; Cvetković, A.; Săvoiu, G. Telework Perceptions and Factors: What to Expect after the COVID-19. In Sustainable Business Management and Digital Transformation: Challenges and Opportunities in the Post-COVID Era; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 509–524. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, W.J.; Belkin, L.Y.; Tuskey, S.E.; Conroy, S.A. Surviving remotely: How job control and loneliness during a forced shift to remote work impacted employee work behaviors and well-being. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2022, 61, 449–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavoille, N.; Hazans, M. Personality Traits, Remote Work and Productivity. IZA Discussion Papers, No. 15486. 2022, pp. 1–47. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4233436 (accessed on 20 November 2022).

- Nguyen, M.H.; Armoogum, J. Perception and Preference for Home-Based Telework in the COVID-19 Era: A Gender-Based Analysis in Hanoi, Vietnam. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biron, M.; Turgeman-Lupo, K.; Levy, O. Integrating push–pull dynamics for understanding the association between boundary control and work outcomes in the context of mandatory work from home. Int. J. Manpow. 2022, 44, 299–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somasundram, K.G.; Hackney, A.; Yung, M.; Du, B.; Oakman, J.; Nowrouzi-Kia, B.; Yazdani, A. Mental and physical health and well-being of Canadian employees who were working from home during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günther, N.; Hauff, S.; Gubernator, P. The joint role of HRM and leadership for teleworker well-being: An analysis during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ger. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2022, 36, 353–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, C.A.; Wallace, L.M.; Spurgeon, P.C. An exploration of the psychological factors affecting remote e-worker’s job effectiveness, well-being and work-life balance. Empl. Relat. Int. J. 2013, 35, 527–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charalampous, M.; Grant, C.A.; Tramontano, C. “It needs to be the right blend”: A qualitative exploration of remote e-workers’ experience and well-being at work. Empl. Relat. Int. J. 2022, 44, 335–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloisi, A.; DE Stefano, V. Essential jobs, remote work and digital surveillance: Addressing the COVID-19 pandemic panopticon. Int. Labour Rev. 2022, 161, 289–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graen, G.B.; Uhl-Bien, M. Relationship-based approach to leadership: Development of leader-member exchange (LMX) theory of leadership over 25 years: Applying a multi-level multi-domain perspective. Leadersh. Q. 1995, 6, 219–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charalampous, M.; Grant, C.A.; Tramontano, C. The Development of the E-Work Well-Being Scale and Further Validation of the e-Work Life Scale. Ph. D. Thesis, Coventry University, London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Grzegorczyk, M.; Mariniello, M.; Nurski, L.; Schraepen, T. Blending the Physical and Virtual: A Hybrid Model for the Future of Work; Bruegel Policy Contribution: Brussels, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Michinov, E.; Ruiller, C.; Chedotel, F.; Dodeler, V.; Michinov, N. Work-From-Home during COVID-19 Lockdown: When Employees’ Well-Being and Creativity Depend on Their Psychological Profiles. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 862987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmitt, J.B.; Breuer, J.; Wulf, T. From cognitive overload to digital detox: Psychological implications of telework during the COVID-19 pandemic. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 124, 106899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vayre, É.; Devif, J.; Gachet-Mauroz, T.; Morin-Messabel, C. Telework: What is at Stake for Health, Quality of Life at Work and Management Methods? In Digitalization of Work: New Spaces and New Working Times; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2022; Volume 5, pp. 73–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Publication Year | Number of Papers | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 3 | 6.25% |

| 2016 | 1 | 2.08% |

| 2019 | 1 | 2.08% |

| 2020 | 6 | 12.50% |

| 2021 | 19 | 39.58% |

| 2022 | 18 | 37.50% |

| 48 | 100.00% |

| Type | Authors | Citations | Title | Journal/Source | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peer-reviewed | Bentley, T. A., Teo, S. T., McLeod, L., Tan, F., Bosua, R., and Gloet, M. 2016 [48] | 529 | The role of organisational support in teleworker wellbeing: A socio-technical systems approach | Applied Ergonomics | 2016 |

| Peer-reviewed | Anderson, A. J.; Kaplan, S. A.; and Vega, R. P. [49] | 333 | The impact of telework on emotional experience: When, and for whom, does telework improve daily affective well-being? | European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology | 2015 |

| Peer-reviewed | Contreras, F.; Baykal, E.; and Abid, G. [10] | 320 | E-leadership and teleworking in times of COVID-19 and beyond: What we know and where do we go | Frontiers in Psychology | 2020 |

| Peer-reviewed | Sostero, M.; Milasi, S.; Hurley, J.; Fernandez-Macías, E.; and Bisello, M. [24] | 226 | Teleworkability and the COVID-19 crisis: a new digital divide? | JRC Working Papers Series on Labour, Education and Technology | 2020 |

| Peer-reviewed | Arntz, M., Ben Yahmed, S., and Berlingieri, F. [50] | 137 | Working from home and COVID-19: The chances and risks for gender gaps | Intereconomics | 2020 |

| Peer-reviewed | Aczel, B., Kovacs, M., Van Der Lippe, T., and Szaszi, B. [51] | 103 | Researchers working from home: Benefits and challenges | PLoS ONE | 2021 |

| “Grey” literature | Brussevich, M., Dabla-Norris, M. E., and Khalid, S. [25] | 103 | Who will Bear the Brunt of Lockdown Policies? Evidence from Tele-workability. Measures across Countries | IMF Working Papers | 2020 |

| Peer-reviewed | de Macêdo, T. A. M., Cabral, E. L. D. S., Silva Castro, W. R., de Souza Junior, C. C., da Costa Junior, J. F., Pedrosa, F. M., … and Másculo, F. S. [52] | 92 | Ergonomics and telework: A systematic review | Journal of Prevention, Assessment & Rehabilitation | 2020 |

| “Grey” literature | Lodovici, M. S. [53] | 58 | The impact of teleworking and digital work on workers and society | EEMPL Committee | 2021 |

| Peer-reviewed | Kim, T.; Mullins, L. B.; Yoon, T. [54] | 52 | Supervision of telework: A key to organizational performance | The American Review of Public Administration | 2021 |

| Peer-reviewed | Vesala, H. and Tuomivaara, S. [55] | 52 | Slowing work down by teleworking periodically in rural settings? | Personnel Review | 2015 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Urien, B. Teleworkability, Preferences for Telework, and Well-Being: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10631. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151310631

Urien B. Teleworkability, Preferences for Telework, and Well-Being: A Systematic Review. Sustainability. 2023; 15(13):10631. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151310631

Chicago/Turabian StyleUrien, Begoña. 2023. "Teleworkability, Preferences for Telework, and Well-Being: A Systematic Review" Sustainability 15, no. 13: 10631. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151310631