Eye-Tracking Studies on Sustainable Food Consumption: A Systematic Literature Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

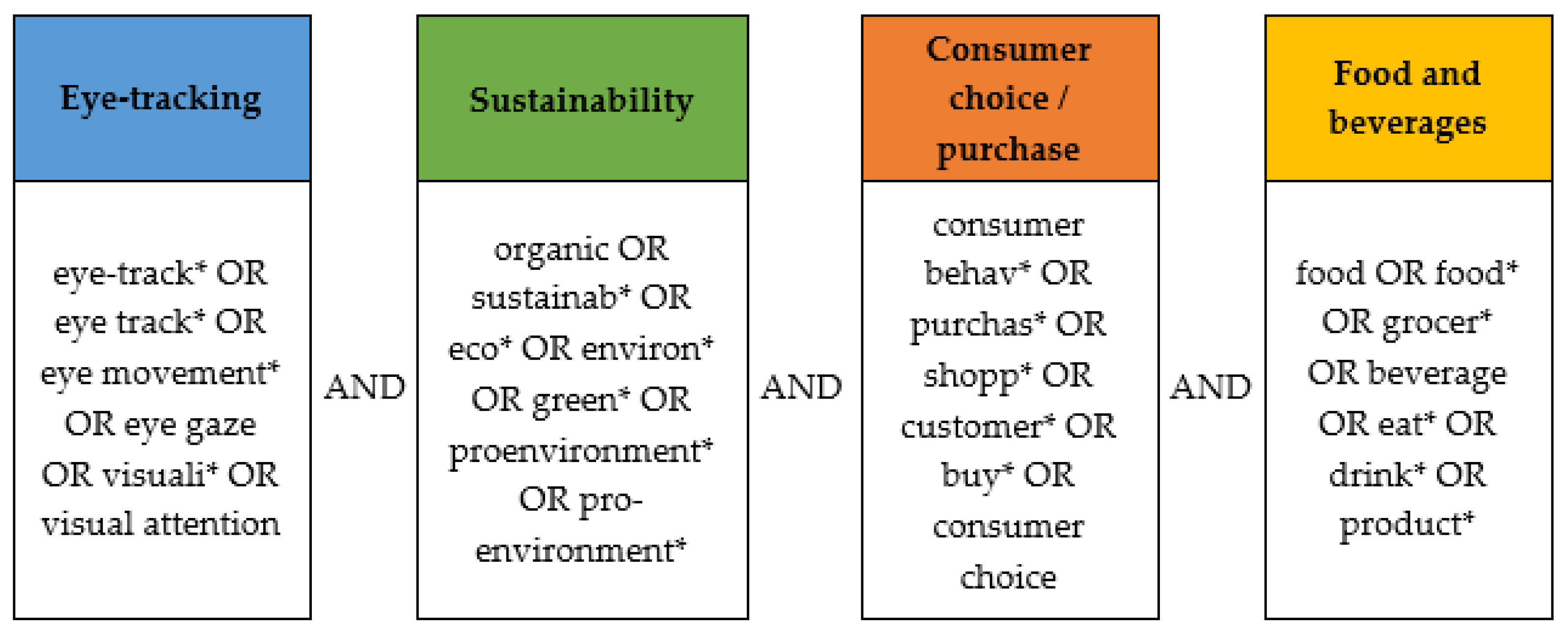

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Application of Eye-Tracking

3.2. Labeling

3.3. Consumer Attention

3.4. Consumer Choice and Preference

3.5. Consumer Attitude and Behavior

3.6. Willingness-to-Pay (WTP)

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Journal | # |

|---|---|

| Agribusiness | 1 |

| Agricultural Economics | 1 |

| Agronomy | 1 |

| Appetite | 1 |

| Behavioral Sciences | 1 |

| Beverages | 1 |

| Business Systems Research | 1 |

| European Review of Agricultural Economics | 1 |

| Foods | 1 |

| Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems | 1 |

| International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health | 1 |

| Journal of Agricultural & Food Industrial Organization | 1 |

| Journal of Agricultural and Applied Economics | 1 |

| Journal of Choice Modelling | 1 |

| Journal of Economic Behaviour & Organization | 1 |

| Journal of Food Products Marketing | 1 |

| Journal of Neuroscience, Psychology, & Economics | 1 |

| Journal of Sustainable Tourism | 1 |

| Psychological Science | 1 |

| Semiotica | 1 |

| Ecological Economics | 2 |

| Journal of Business Research | 2 |

| Journal of Cleaner Production | 2 |

| Journal of Retailing & Consumer Services | 2 |

| Sustainability | 4 |

| Food Quality and Preference | 6 |

| Research Area | Count | % |

|---|---|---|

| Business and Economics | 14 | 25.000 |

| Food Science and Technology | 11 | 19.643 |

| Environmental Sciences and Ecology | 8 | 14.286 |

| Science and Technology—Other Topics | 7 | 12.500 |

| Agriculture | 4 | 7.143 |

| Psychology | 3 | 5.357 |

| Engineering | 2 | 3.571 |

| Social Sciences—Other Topics | 2 | 3.571 |

| Arts and Humanities—Other Topics | 1 | 1.786 |

| Behavioural Sciences | 1 | 1.786 |

| Nutrition and Dietetics | 1 | 1.786 |

| Plant Sciences | 1 | 1.786 |

| Public, Environmental and Occupational Health | 1 | 1.786 |

| Research Area | Count | % |

|---|---|---|

| Food Science and Technology | 11 | 16.667 |

| Environmental Sciences | 9 | 13.636 |

| Economics | 8 | 12.121 |

| Green and Sustainable Science and Technology | 7 | 10.606 |

| Business | 6 | 9.091 |

| Environmental Studies | 6 | 9.091 |

| Agricultural Economics and Policy | 4 | 6.061 |

| Psychology, Multidisciplinary | 3 | 4.545 |

| Ecology | 2 | 3.030 |

| Engineering, Environmental | 2 | 3.030 |

| Agronomy | 1 | 1.515 |

| Behavioral Sciences | 1 | 1.515 |

| Hospitality, Leisure, Sport and Tourism | 1 | 1.515 |

| Humanities, Multidisciplinary | 1 | 1.515 |

| Nutrition and Dietetics | 1 | 1.515 |

| Plant Sciences | 1 | 1.515 |

| Public, Environmental and Occupational Health | 1 | 1.515 |

| Social Sciences, Interdisciplinary | 1 | 1.515 |

Appendix B

| Corresponding Measure | Measure in Reviewed Studies | Authors |

|---|---|---|

| Dwell time |

| [21,31,32,37,39,41,47,51,54] |

| Fixation count |

| [13,17,32,34,35,42,43,44,45,48,52,53,54,57,58] |

| Fixation distribution |

| [40] |

| Fixation duration |

| [13,17,22,24,34,35,36,40,42,43,44,45,48,51,53,55,56,57,61] |

| First fixation |

| [5,33] |

| Fixation likelihood |

| [14,46,49,50] |

| Number of intervalsto first fixation |

| [33] |

| Return visits |

| [24] |

| Saccades count |

| [43] |

| Saccades duration |

| [43] |

| Time to first fixation |

| [13,17,24,31,40,42,47,51,54,55] |

| Visit count |

| [17,44,45,48] |

| Visit duration |

| [5,17,38,42,44,45,48,59,60] |

References

- Anantharaman, M. Critical sustainable consumption: A research agenda. J. Environ. Stud. Sci. 2018, 8, 553–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaskas, S.; Panagiotarou, A.; Rigou, M. Impact of environmental concern, emotional appeals, and attitude toward the advertisement on the intention to buy green products: The case of younger consumer audiences. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waechter, S.; Sütterlin, B.; Siegrist, M. Desired and undesired effects of energy labels—An eye-tracking study. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0134132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Messer, K.D.; Costanigro, M.; Kaiser, H.M. Labeling food processes: The good, the bad and the ugly. Appl. Econ. Perspect. Policy 2017, 39, 407–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L.; Lim, Y.; Chang, P.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, M.; Wang, X.; Yu, X.; Lehto, M.R.; Cai, H. Ecolabel’s role in informing sustainable consumption: A naturalistic decision making study using eye tracking glasses. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 218, 685–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orquin, J.L.; Mueller Loose, S. Attention and choice: A review on eye movements in decision making. Acta Psychol. 2013, 144, 190–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Loo, E.J.; Grebitus, C.; Nayga, R.M.; Verbeke, W.; Roosen, J. On the measurement of consumer preferences and food choice behavior: The relation between visual attention and choices. Appl. Econ. Perspect. Policy 2018, 40, 538–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, D.J.; Orquin, J.L.; Visschers, V.H. Eye tracking and nutrition label use: A review of the literature and recommendations for label enhancement. Food Policy 2012, 37, 378–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, G.; Zhuang, X. Nutrition label processing in the past 10 years: Contributions from eye tracking approach. Appetite 2021, 156, 104859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liaukonyte, J.; Streletskaya, N.A.; Kaiser, H.M.; Rickard, B.J. Consumer response to “contains” and “free of” labeling: Evidence from lab experiments. Appl. Econ. Perspect. Policy 2013, 35, 476–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgianni, Y.; Maccioni, L.; Dignös, A.; Basso, D. A framework to evaluate areas of interest for sustainable products and designs. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bialkova, S.; van Trijp, H.C. An efficient methodology for assessing attention to and effect of nutrition information displayed front-of-pack. Food Qual. Prefer. 2011, 22, 592–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Serrano, P.; Tarancón, P.; Bonet, L.; Besada, C. Consumers’ visual attention and choice of ‘Sustainable Irrigation’-Labeled Wine: Logo vs. Text. Agronomy 2022, 12, 685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orquin, J.L.; Bagger, M.P.; Lahm, E.S.; Grunert, K.G.; Scholderer, J. The visual ecology of product packaging and its effects on consumer attention. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 111, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ares, G.; Giménez, A.; Bruzzone, F.; Vidal, L.; Antúnez, L.; Maiche, A. Consumer visual processing of food labels: Results from an eye-tracking study. J. Sens. Stud. 2013, 28, 138–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieters, R.; Wedel, M. Attention capture and transfer in advertising: Brand, pictorial, and text-size effects. J. Mark. 2004, 68, 36–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giray, C.; Yon, B.; Alniacik, U.; Girisken, Y. How does mothers’ mood matter on their choice of organic food? Controlled eye-tracking study. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 144, 1175–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wedel, M.; Pieters, R. A review of eye-tracking research in marketing. In Review of Marketing Research; Malhotra, N.K., Ed.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2008; pp. 123–147. ISBN 978-0-7656-2092-7. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, D.J.; Jeffery, R.W. Location, location, location: Eye-tracking evidence that consumers preferentially view prominently positioned nutrition information. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2011, 111, 1704–1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visschers, V.H.M.; Hess, R.; Siegrist, M. Health motivation and product design determine consumers’ visual attention to nutrition information on food products. Public Health Nutr. 2010, 13, 1099–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drexler, D.; Fiala, J.; Havlíčková, A.; Potůčková, A.; Souček, M. The effect of organic food labels on consumer attention. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2018, 24, 441–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamberz, J.; Litfin, T.; Teckert, Ö.; Meeh-Bunse, G. Is there a link between sustainability, perception and buying decision at the point of sale? Bus. Syst. Res. 2020, 11, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharafi, Z.; Soh, Z.; Guéhéneuc, Y.-G. A systematic literature review on the usage of eye-tracking in software engineering. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2015, 67, 79–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leon, F.A.; Spers, E.E.; de Lima, L.M. Self-esteem and visual attention in relation to congruent and non-congruent images: A study of the choice of organic and transgenic products using eye tracking. Food Qual. Prefer. 2020, 84, 103938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, F.; Khattak, A.; Ur Rehman, S.; Ashiq, M. Bibliometric analysis of green marketing research from 1977 to 2020. Publications 2021, 9, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homar, A.R.; Cvelbar, L.K. The effects of framing on environmental decisions: A systematic literature review. Ecol. Econ. 2021, 183, 106950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delafrooz, N.; Taleghani, M.; Nouri, B. Effect of green marketing on consumer purchase behavior. QSci. Connect 2014, 2014, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahbar, E.; Abdul Wahid, N. Investigation of green marketing tools’ effect on consumers’ purchase behavior. Bus. Strategy Ser. 2011, 12, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babakhani, N.; Lee, A.; Dolnicar, S. Carbon labels on restaurant menus: Do people pay attention to them? J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 51–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balcombe, K.; Fraser, I.; Williams, L.; McSorley, E. Examining the relationship between visual attention and stated preferences: A discrete choice experiment using eye-tracking. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2017, 144, 238–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beattie, G.; McGuire, L. Harnessing the unconscious mind of the consumer: How implicit attitudes predict pre-conscious visual attention to carbon footprint information on products. Semiotica 2015, 204, 253–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conoly, Y.K.; Lee, Y.M. Intrinsic and extrinsic cue words of locally grown food menu items and consumers’ choice at hyper-local restaurants: An eye-tracking study. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudinskaya, E.C.; Naspetti, S.; Zanoli, R. Using eye-tracking as an aid to design on-screen choice experiments. J. Choice Model. 2020, 36, 100232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gidlöf, K.; Lahm, E.S.; Wallin, A.; Otterbring, T. Eco depletion: The impact of hunger on prosociality by means of environmentally friendly attitudes and behavior. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 62, 102654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grebitus, C.; Roosen, J.; Seitz, C.C. Visual attention and choice: A behavioral economics perspective on food decisions. J. Agric. Food Ind. Organ. 2015, 13, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grebitus, C.; van Loo, E.J. Relationship between cognitive and affective processes, and willingness to pay for pesticide-free and GMO-free labeling. Agric. Econ. 2022, 53, 407–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyader, H.; Ottosson, M.; Witell, L. You can’t buy what you can’t see: Retailer practices to increase the green premium. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 34, 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmert, J.R.; Symmank, C.; Pannasch, S.; Rohm, H. Have an eye on the buckled cucumber: An eye tracking study on visually suboptimal foods. Food Qual. Prefer. 2017, 60, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismael, D.; Ploeger, A. Consumers’ emotion attitudes towards organic and conventional food: A comparison study of emotional profiling and self-reported method. Foods 2020, 9, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, M.; Campbell, B.; Liu, Y. Local and organic preference: Logo versus text. J. Agric. Appl. Econ. 2019, 51, 328–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maccioni, L.; Borgianni, Y.; Basso, D. Value perception of green products: An exploratory study combining conscious answers and unconscious behavioral aspects. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyerding, S.G.H.; Merz, N. Consumer preferences for organic labels in Germany using the example of apples—Combining choice-based conjoint analysis and eye-tracking measurements. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 181, 772–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyerding, S.G.H. Combining eye-tracking and choice-based conjoint analysis in a bottom-up experiment. J. Neurosci. Psychol. Econ. 2018, 11, 28–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oselinsky, K.; Johnson, A.; Lundeberg, P.; Holm, A.J.; Mueller, M.; Graham, D.J. GMO food labels do not affect college student food selection, despite negative attitudes towards GMOs. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, E.; Kilic, B.; Cubero Dudinskaya, E.; Naspetti, S.; Solfanelli, F.; Zanoli, R. Message in a bottle: An exploratory study on the role of wine-bottle design in capturing consumer Attention. Beverages 2023, 9, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padilha, L.G.; Malek, L.; Umberger, W.J. Sustainable meat: Looking through the eyes of Australian consumers. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkovic, S.; Orquin, J.L. Implicit statistical learning in real-world environments leads to ecologically rational decision making. Psychol. Sci. 2018, 29, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peschel, A.O.; Orquin, J.L.; Loose, S.M. Increasing consumers’ attention capture and food choice through bottom-up effects. Appetite 2019, 132, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proi, M.; Dudinskaya, E.C.; Naspetti, S.; Ozturk, E.; Zanoli, R. The role of eco-labels in making environmentally friendly choices: An eye-tracking study on aquaculture products with Italian consumers. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rihn, A.L.; Yue, C. Visual attention’s influence on consumers’ willingness-to-pay for processed food products. Agribusiness 2016, 32, 314–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samant, S.S.; Seo, H.S. Effects of label understanding level on consumers’ visual attention toward sustainability and process-related label claims found on chicken meat products. Food Qual. Prefer. 2016, 50, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sola, H.M.; Kljusuric, J.G.; Roncevic, I. The impact of bio-label on the decision-making behavior. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2022, 6, 1002521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Songa, G.; Slabbinck, H.; Vermeir, I.; Russo, V. How do implicit/explicit attitudes and emotional reactions to sustainable logo relate? A neurophysiological study. Food Qual. Prefer. 2019, 71, 485–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, R.; Todo, Y.; Funaki, Y. How can we motivate consumers to purchase certified forest coffee? Evidence from a laboratory randomized experiment using eye-trackers. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 150, 107–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Loo, E.J.; Caputo, V.; Nayga, R.M., Jr.; Seo, H.-S.; Zhang, B.; Verbeke, W. Sustainability labels on coffee: Consumer preferences, willingness-to-pay and visual attention to attributes. Ecol. Econ. 2015, 118, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Loo, E.J.; Nayga, R.M., Jr.; Campbell, D.; Seo, H.-S.; Verbeke, W. Using eye tracking to account for attribute non-attendance in choice experiments. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2018, 45, 333–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Loo, E.J.; Grebitus, C.; Roosen, J. Explaining attention and choice for origin labeled cheese by means of consumer ethnocentrism. Food Qual. Prefer. 2019, 78, 103716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Loo, E.J.; Grebitus, C.; Verbeke, W. Effects of nutrition and sustainability claims on attention and choice: An eye-tracking study in the context of a choice experiment using granola bar concepts. Food Qual. Prefer. 2021, 90, 104100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.J.; Hou, C.X.; Zhang, M.M.; Niu, J.C.; Lai, Y.; Fu, H.L. Leveraging user comments for the construction of recycled water infrastructure-evidence from an eye-tracking experiment. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammann, J.; Arbenz, A.; Mack, G.; Nemecek, T.; El Benni, N. A review on policy instruments for sustainable food consumption. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2023, 36, 338–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, R.; Nyström, M.; Holmqvist, K. Sampling frequency and eye-tracking measures: How speed affects durations, latencies, and more. J. Eye Mov. Res. 2010, 3, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leube, A.; Rifai, K. Sampling rate influences saccade detection in mobile eye tracking of a reading task. J. Eye Mov. Res. 2017, 10, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wedel, M.; Pieters, R. Eye fixations on advertisements and memory for brands: A model and findings. Mark. Sci. 2000, 19, 297–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janiszewski, C. The influence of display characteristics on visual exploratory search behavior. J. Consum. Res. 1998, 25, 290–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ares, G.; Mawad, F.; Giménez, A.; Maiche, A. Influence of rational and intuitive thinking styles on food choice: Preliminary evidence from an eye-tracking study with yogurt labels. Food Qual. Prefer. 2014, 31, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunert, K.G. Sustainability in the food sector: A consumer behaviour perspective. Int. J. Food Syst. Dyn. 2011, 2, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pernice, K.; Nielsen, J. How to Conduct Eye Tracking Studies. Available online: https://media.nngroup.com/media/reports/free/How_to_Conduct_Eyetracking_Studies.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2023).

- Huddleston, P.T.; Behe, B.K.; Driesener, C.; Minahan, S. Inside-outside: Using eye-tracking to investigate search-choice processes in the retail environment. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 43, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinhardt, G.; Gärtner, S.; Wagner, T. Ökologische Fußabdrücke von Lebensmitteln und Gerichten in Deutschland. Available online: https://www.umweltbundesamt.de/sites/default/files/medien/6232/dokumente/ifeu_2020_oekologische-fussabdruecke-von-lebensmitteln.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2023).

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, K.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author (Year) | Sampling Country | Food | Sample Size after Eye-Tracking and Participant Information | Sustainable Stimuli | Apparatus | Methodology | Measure | Key Findings on Sustainable Food Consumption |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Babakhani, N. et al., (2020) [31] | Australia | Menu: 6 burgers, 4 drinks, and 4 desserts | 54 (17 control, 19 carbon label, and 18 local farmer group) 17–67 years, 32 years on average and 62% female | Local farmer and carbon footprint label | Desktop mounted eye-tracker Tobii TX-300 (300 Hz) [Tobii AB, Danderyd, Sweden] | Eye-tracking, interview, questionnaire | Dwell time, time to first fixation | Carbon and local farmer labels do not influence menu choices and capture little consumer attention. |

| Balcombe, K. et al., (2017) [32] | UK | Meat on pepperoni pizza | 100 Wide range of ages (larger portion of young people than in the population as well as few participants over 55 years), 53 female and 47 male | Organic and country-of-origin label (farming system) | EyeLink II, SR Research (500 Hz) [SR Research Ltd., Ottawa, ON, Canada] | Eye-tracking, questionnaire | Dwell time, fixation count | Consumers who value sustainable characteristics of food (organic, country-of-origin) are more likely to pay attention to these characteristics. |

| Beattie, G. & McGuire, L. (2015) [33] | UK | Muesli, washing powder, ice lollies, and cake mix | 32 University undergraduates | Carbon footprint label | ASL Model 504 remote eye tracker (120 Hz) [Applied Sciences Laboratory, Spokane, WA, USA] and mpeg2 video editing program | Eye-tracking, implicit association test, questionnaire | First fixation, number of intervals to first fixation | Consumers with a positive attitude toward carbon footprint do not spend significantly more time paying attention to the carbon footprint label, but they are more likely to pay attention to it first (than to other labels) than consumers with a more negative attitude. Carbon footprint labeling stands out for some consumers when the size of the label is matched with other labels. |

| Conoly, Y.K. and Lee, Y.M. (2023) [34] | USA | Menu choice | 50 19–64 years, 30.76 years on average, 26 (52%) female and 24 (48%) male, 56% (n = 28) Undergraduate or graduate students | Region-of-origin (local) label | Tobii X2-60 screen-based eye tracker [Tobii AB, Danderyd, Sweden], 17-inch monitor (1280 × 1024 pixel), and Tobii Studio Analysis 1.152 software | Eye-tracking, questionnaire | Fixation count, fixation duration | The extrinsic cue word local on menu choices relates to visual attention. Participants who choose the menu item with the word local appear to look at it more frequently before making their final menu selection. |

| Drexler, D. et al., (2018) [21] | Czech Republic | Cucumbers, peppers, apple juice, milk, mead, yogurt, and flour | 147 (88 experimental group and 59 control group) 20–23 years, 64 female and 24 male experimental group, 41 female and 18 male control group Students | Local and organic label | SMI RED 250 (250 Hz) [SensoMotoric Instruments, Teltow, Germany] | Eye-tracking, interviews | Dwell time | Eco-labels (local or organic label) attract consumer attention and play a role in decision-making, but a third of the consumers pay no attention to them. |

| Dudinskaya, E. et al., (2020) [35] | Italy | Ruminants’ meat | 23 24 years average age, 8 female and 15 male Young participants (students) and meat consumers | Country-of-origin, organic, Halal, animal feeding, protected geographical indication, and carbon footprint label | Tobii X2-60 screen-based eye-tracker (60 Hz) [Tobii AB, Danderyd, Sweden] with iMotions software | Choice experiment, eye-tracking, questionnaire | Fixation count, fixation duration | Origin and organic labels have a significant positive effect on consumer choice, but a third of the consumers choose their meat without paying attention to its origin. |

| Fernández-Serrano, P. et al., (2022) [13] | Spain | Wine | 64 (32 front-labels and 32 back-labels) 18–63 years front-labels and 18–61 years back-labels | Sustainable Irrigation label | Tobii Pro-Nano screen-based eye-tracker [Tobii AB, Danderyd, Sweden] with Tobii Pro Lab-Full Edition 1.152 software (60 Hz) | Choice experiment, eye-tracking, questionnaire | Fixation count, fixation duration, time to first fixation | Consumers prefer logo and picture labels over text labels. Consumer choice is directly related to the attention they pay to sustainable irrigation label. Consumers are willing to pay a premium for products (wine) with sustainable production characteristics. |

| Gidlöf, K. et al., (2021) [36] | Sweden | Pasta | Study 1: 60, study 2: 100 Study 1: 24.25 years average age, 21 female and 39 male Study 2: 25 years average age, 58 female and 42 male | Organic label | Study 1: Tobii Pro [Tobii AB, Danderyd, Sweden] Glasses 2 (50 Hz) Study 2: Tobii Pro Spectrum eye tracker (1200 Hz) [Tobii AB, Danderyd, Sweden] | Eye-tracking, questionnaire | Fixation duration | Visual attention and consumer choices to eco-labelled food options is relative equal among hungry or satiated consumers. |

| Giray, C. et al., (2022) [17] | Turkey | Banana, apple, strawberry, carrot, and tomato | 60 (30 experiment group and 30 control group) 20–45 years, 60 woman all with children aged 0–18 | Organic label (organic purchase decisions and consumption) | Tobii T120 (120 Hz) [Tobii AB, Danderyd, Sweden], 17-inch monitor (1280 × 1024 pixel), Adobe Flash software, and Attention Toll 5.2 software | Eye-tracking, questionnaire | Fixation count, fixation duration, time to first fixation, visit count, visit duration | The price of organic products has a significant negative impact on the purchase of organic products, but visual attention (longer gaze at the organic area) increases the likelihood of a purchase. The level of knowledge correlates with organic purchases. |

| Grebitus, C. et al., (2015) [37] | USA | Cheddar cheese | 130 Higher share of younger participants, 65 female and 65 male, better educated and higher income on average than the general population, household size on average between 2 and 3 | Hormone-free, country-of-origin, region-of-origin, and biodegradable packaging label | Tobii R T60 XL screen-based eye-tracker (60 Hz) [Tobii AB, Danderyd, Sweden] and Tobii Studio 2.2 software | Choice experiment, eye-tracking | Dwell time | Applying organic labels has a significant and positive effect on consumer decisions and choice. The probability of choosing an organic product decreases if consumers are not familiar with it. However, visual attention probably works against this behavior. |

| Grebitus, C. and van Loo, E.J. (2022) [38] | USA | Medjool dates | 117 30 years average age, 56.4% female and 43.6% male, slightly higher than income of the population | Pesticide-free and genetically modified organisms-free (GMO-free) label | Tobii T60 XL screen-based eye-tracker (60 Hz) [Tobii AB, Danderyd, Sweden] and Tobii Studio 2.2 software | Choice experiment, eye-tracking, questionnaire | Visit duration | Consumers are willing to pay a premium for products with sustainable production characteristics. Higher visual attention to a particular production method label brings with it consumer concerns and consumer attachment to the region. |

| Guyader, H. et al., (2017) [39] | Sweden | Coffee and fabric softener | 66 23 year average age Students | Organic and fair-trade label (colored price tags to signal eco-friendly products) | SMI eye-tracking glasses (60 Hz and 1280x 960 pixel video resolution) [SensoMotoric Instruments, Teltow, Germany] with SMI BeGaze software | Eye-tracking | Dwell time | Participants paying attention to environmentally friendly food pay a premium. Priming can increase consumers’ visual attention to sustainable labeling. The color green influences visual attention since it is associated with organic and natural characteristics. |

| Helmert, J.R. et al., (2017) [40] | Germany | Cucumber, banana, piece of butter, juice carton, carrot, apple, milk carton, and pile of cookies | 30 40 years average age, 21 female | Visually suboptimal food | EyeLink 1000 eye-tracking system (1000 Hz) [SR Research Ltd., Ottawa, Ontario, CA] and 19-inch CRT monitor (Iiyama Vision Master 451; screen resolution 1024 × 768 pixels) | Eye-tracking, questionnaire | Fixation distribution, fixation duration, time to first fixation | Consumers prefer impeccable food compared to suboptimal food when shopping. When impeccable and suboptimal foods have differently designed price tags, a positive trend towards purchasing suboptimal food emerges. |

| Ismael, D. and Ploeger, A. (2020) [41] | Germany | Apple, orange juice (bottles), walnut, oregano, red bell pepper, coffee, and pear fruit | 46 19–48 years, 65% female and 35% male, 96% moderate to very good level of knowledge on organic food, 75% students, 20% employees, and 5% neither students nor employees | Organic label (organic and conventional sample) | SMI RED-250 screen-based eye-tracker (60 Hz) [SensoMotoric Instruments, Teltow, Germany] | Choice experiment, eye-tracking, questionnaire | Dwell time | There are no significant differences in implicit food-elicited emotions between organic and conventional food items. |

| Katz, M. et al., (2019) [42] | USA | Apples, blueberries, and sweet corn | 255 (88 apples, 81 blueberries, and 86 sweet corn) 37, 44, and 38 years average age (apple, blueberries, and sweet corn), 60%, 57%, and 69% female | Organic and country-of-origin label Sustainably (certified organic, local) grown logo labeled vs. text labeled produce | Tobii X1 Light screen-based eye-tracker (60 Hz) [Tobii AB, Danderyd, Sweden] and Tobii Studio 3.0.2.218 software | Choice experiment, eye-tracking | Fixation count, fixation duration, time to first fixation, visit duration | Local logo labels attract consumer attention quicker and have a longer eye-tracking time than text labels. Consumers prefer local and organic products to non-local and non-organic products. Consumers are also willing to pay a higher price for products with logo labels than for products with text or no labels. |

| Lamberz, J. et al., (2020) [22] | Germany | Juice | 32 | Organic label Sustainable and regional food (regionality) | Tobii Pro Glasses 2 (50 or 100 Hz) [Tobii AB, Danderyd, Sweden] | Eye-tracking, questionnaire | Fixation duration | Consumer with a positive attitude towards sustainable food fixate on sustainable packaging and sustainable display elements longer, deal more intensively with product information, and are more likely to remember sustainable product features and individual display elements. Sustainable information is more likely to be perceived by consumers if it is displayed at eye-level. A positive attitude towards sustainability tends to increase the willingness-to-pay for sustainable food. |

| Leon, F.A. et al., (2020) [24] | Brazil | Transgenic and organic products | 30 18–30 years Study or work at the university campus | Organic label Organic and non-organic products | Tobii T120 screen-based eye-tracker (120 Hz) [Tobii AB, Danderyd, Sweden] and 17-inch monitor | Choice experiment, eye-tracking | Fixation duration, time to first fixation, return visits | Visual attention is influenced by self-esteem and image congruence in food decision-making. Women are more likely to buy food with sustainable logos than men because they are associated with high self-esteem behavior. |

| Maccioni, L. et al., (2019) [43] | Italy | Different products (not all foods) | 43 20–45 years, 20 female and 23 male, various backgrounds Approx. half currently studying or have studied engineering while the other ones were mainly involved in humanistic studies | Green products (communicating sustainable features) | Tobii X2-60 Hz screen-based eye-tracker (60 Hz) [Tobii AB, Danderyd, Sweden], 23-inch LCD color monitor, TEA Captiv T-Sens GSR, and Tobii Pro Studio software | Eye-tracking, questionnaire | Fixation count, fixation duration, saccades count, saccades duration | Consumers’ interest in sustainability issues is not reflected in their consumption decisions. Sustainable foods cause no increased emotional involvement among consumers than conventional foods. Price is a relevant issue and consumers may be discouraged from purchasing green products. |

| Meyerding, S.G.H. and Merz, N. (2018) [44] | Germany | Braeburn apples | 73 34.86 years average age, 35 female and 38 male | Organic label | Tobii Pro Glasses 2 (50 Hz) [Tobii AB, Danderyd, Sweden], 27-inch flat screen monitor with a common resolution of 1280 × 1024 pixel, and Tobii Pro Lab 1.58 software | Choice experiment, eye-tracking, questionnaire | Fixation count, fixation duration, visit count, visit duration | Low-involvement products attract less visual attention than high-involvement products. Different organic labels play a less important role in decision-making processes than expected since visual attention influences purchase decision-making processes. Higher prices tend to reduce the purchase probability. |

| Meyerding, S.G.H. (2018) [45] | Germany | Tomatoes | 17 27 years average age, 10 female and 7 male | Organic, country-of origin, fair-trade, and carbon footprint label | Tobii Pro Glasses 2 (50 or 100 Hz) [Tobii AB, Danderyd, Sweden], 42-inch screen, and Tobii Pro Lab 1.55.5126 (x64) software | Choice experiment, eye-tracking, questionnaire | Fixation count, fixation duration, visit count, visit duration | Unless it is a top-down situation, there is no significant relationship between visual attention and selection. Picture labels receive more visual attention than text labels. Higher and lower prices receive more visual attention than medium prices. |

| Orquin, J.L. et al., (2020) [14] | Denmark | Consumer products (packaged dairy product categories) | Study 1: 91 Study 2: no eye-tracking 21–59 years | Organic and Keyhole label | Tobii 2150 screen-based eye-tracker (50 Hz) [Tobii AB, Danderyd, Sweden], EyeLink 1000 (1000 Hz) [SR Research Ltd., Ottawa, Ontario, CA], and Tobii Studio Software | Choice experiment, eye-tracking | Fixation likelihood | Salience, size, and distance (bottom-up factors) increase the likelihood that consumers fixate on food. The preference for brand-related elements leads to the neglect of sustainable elements. |

| Oselinsky, K. et al., (2021) [46] | USA | Different foods from food categories, including cookies, ice creams, crackers, nuts, chips, salty snacks (pretzels, cheese puffs, and rice cakes), yogurts, soups, cereals, meats, pizzas, canned fruit, canned vegetables, and frozen fruit and vegetables | 434 (203 phase 1: 70 GMO free, 63 contains GMOs, and 70 control; 231 phase 2: 61 GMO free, 128 contains GMOs, and 42 control) 19 years average age (generation z), 62% female phase 1 and 61% female phase 2, Undergraduate students | GMO-free label | EyeLink 1000 (1000 Hz) [SR Research Ltd., Ottawa, Ontario, CA] | Choice experiment, eye-tracking, questionnaire | Fixation likelihood | Consumers who at least once fixate on sustainable labels spend some portion of time looking at them. Consumers pay attention to sustainable labels, but the labels have no significant impact on food choices. |

| Ozturk, E. et al., (2023) [47] | Italy | Two different shaped wine bottles | 24 20–59 years (30.25 years average age), equal gender distribution Students and non-research staff from university | Organic label | Tobii X2-60 screen-based eye-tracker (60 Hz) [Tobii AB, Danderyd, Sweden], LCD monitor with a resolution of 1920 × 1080 pixel, and iMotions 7.1 software (60 Hz) | Eye-tracking | Dwell time, time to first fixation | Shoulder area and the top of a bottle are the best parts for drawing consumers’ visual attention and interest to organic labels. The type of bottle determines the choice of the best place for the organic label. |

| Padilha, L.G. et al., (2021) [48] | Australia | Chicken meat products | 30 Older than 18 years, 60% female and 40% male, 8% university degree | RSPC approved farming scheme, free-range, accredited free-range, and antibiotic-free label | Tobii Pro TX300 screen-based eye-tracker (300 Hz) [Tobii AB, Danderyd, Sweden] and Tobii Pro Lab 1.123 software | Choice experiment, eye-tracking, interview, questionnaire | Fixation count, fixation duration, visit count, visit duration | Consumers notice (fixate on) most sustainable labels. |

| Perkovic, S. and Orquin, J.L. (2018) [49] | Denmark | Choice sets of processed foods | 71 18–74 years (45.73 years average age), 19 female and 52 male | Organic and Keyhole label | Tobii T60 XL screen-based eye-tracker (60 Hz) [Tobii AB, Danderyd, Sweden] and screen resolution of 1920 × 1200 pixel | Eye-tracking, questionnaire | Fixation likelihood | Consumers generally prefer products with two organic labels over products with either one label or no label. For non-label users, the choice is almost random for products with organic labels. When organic food and healthy food are positively correlated, consumers pay more attention to organic food when assessing the healthiness of food. In this case consumers are more likely to focus on the organic information and more likely to choose products with an organic label. |

| Peschel A.O. et al., (2019) [50] | Denmark | Tomatoes, chocolate, and yoghurt | 127 75% in the 18–24 year age group, 57% female Students (57% undergraduate students) | Organic label | Tobii T60 XL screen-based eye-tracker (60 Hz) [Tobii AB, Danderyd, Sweden] and Tobii Studio software | Choice experiment, eye-tracking | Fixation likelihood | A larger and visually more eye-catching label significantly increases the fixation likelihood of that organic label. The consumers’ fixation on the organic label decides whether they choose the product or not, same as the design of the organic label. |

| Proi, M. et al., (2023) [51] | Italy | Smoked salmon and smoked sea bass | 61 18–64 years, 54% female and 46% male, students and workers, most participants were aged between 35 and 44 years, had a doctoral degree and were employed | Aquaculture Stewardship Council (ASC), Friend of the Sea, and GGN certified aquaculture label | Tobii X2-60 screen-based eye-tracker (60 Hz) [Tobii AB, Danderyd, Sweden], 22-inch monitor screen, and iMotions Attention Tool 8.0 software | Choice experiment, eye-tracking | Dwell time, fixation duration, time to first fixation | Size and salience of eco-labels influence visual attention. Larger organic labels, but not higher salience, help consumers cognitively process the organic label. Shape, symbols, and the language in which the organic label is written influence consumer preference. |

| Rihn, A.L. and Yue, C. (2016) [52] | USA | Apple juice and salad mix | 93 51 years average age without young (<12 years old) children at home, 73% female | Organic, country-of-origin, and nutrient content claim label | Tobii X1 Light Eye Tracker (60 Hz) [Tobii AB, Danderyd, Sweden] | Experimental auction, eye-tracking, questionnaire | Fixation count | Consumers are willing to pay a premium for local produced food. |

| Samant, S.S. and Seo, H.S. (2016) [53] | USA | Chicken breast meat products | 29 44 years average age, 18 female and 11 male | Organic label | RED, SMI eye-tracker (120 Hz) [SensoMotoric Instruments, Teltow, Germany], 22-inch monitor screen, stimulus presentation software (Experiment suite 360 TM), and BeGaze software | Eye-tracking | Fixation count, fixation duration | Consumers who are familiar with sustainable labels pay attention to them for longer than consumers who are not. When the meaning and purpose of organic labels are understood, visual attention and positive purchase intention are pronounced. |

| Sola, H.M. et al., (2022) [54] | Croatia | Mashed tomato and mix of spices | 33 18–65 years | Organic and Bio label | Tobii Sticky online platform for webcam-based eye-tracking (15 Hz) [Tobii AB, Danderyd, Sweden], Tobii Sticky software, and G*Power | Eye-tracking, questionnaire | Dwell time, fixation count, time to first fixation | The color of the organic label matters. Organic labeling is essential for organic packaging and must be highlighted on the packaging. |

| Song, L. et al., (2019) [5] | USA | Product categories: bakery, beverage, canned/jarred/ dried goods, cooking/baking goods and spices, dairy, frozen food, health, and seafood, kitchen/ cleaning/ bathroom supplies, meat and seafood, produce, snacks, and others | 156 | Organic, non- GMO, certified Humane, Program for the Endorsement of Forest Certification (PEFC), Sustainable Forestry Initiative, 100% recycled paperboard, Forest Stewardship Council, Dolphin Safe, Rainforest Alliance certified, Fair-trade certified, and transitional certified by QAI label | Tobii Pro Glasses 2 (50 or 100 Hz) [Tobii AB, Danderyd, Sweden] and Tobii Pro Lab software | Eye-tracking, observation, questionnaire | First fixation, visit duration | Organic labels are neither the first nor the longest fixated products in consumers’ product evaluation process. Organic labels receive little attention in competition with other product information. Consumers are less price sensitive when purchasing eco-labelled products and expect better product quality. Consumers rely on habitual shopping (54% of consumers do not fixate on any product information for the items they buy). |

| Songa, G. et al., (2019) [55] | Belgium | Dairy products | 89 20–25 years (22 years average age), 67% female Students | Recyclable label | SMI-RED250 eye-tracker (250 Hz) [SensoMotoric Instruments, Teltow, Germany], Dell 17.3-inch monitor, and face recoding software (Noldus FaceReader5) | Face reader, eye-tracking, implicit association test, questionnaire | Fixation duration, time to first fixation | The amount of time consumers view logos and the spontaneous emotional response dependents on consumers’ implicit attitudes. A positive implicit attitude towards sustainability means that an organic label is recognized more quickly. The longer consumers fixate on an organic label, the stronger the connection between implicit attitudes and spontaneous emotional reaction. |

| Takahashi, R. et al., (2018) [56] | Japan | Coffee | 246 (123 group with information and 123 group without information) 21 years average age, 47% female (41% female group with information and 53% female group without information) Students | Certified coffee | Tobii T60 screen-based eye-tracker (60 Hz) [Tobii AB, Danderyd, Sweden] and 17-inch single-screen | Choice experiment, eye-tracking, questionnaire | Fixation duration | Images of forests on certified forest coffee labels attract consumers’ visual attention and further stimulate the actual purchase of certified forest coffee. Information about the certification program displayed on the certified coffee has no purchasing effect. Awareness and level of interest in sustainability issues of certified coffee and purchase experiences have no influence on consumer-purchasing behavior. Consumers’ visual attention to the certification program logo, coffee product name, or a promotional statement does not influence choice. |

| van Loo, E.J. et al., (2015) [57] | USA | Roasted ground coffee | 81 Each age and income category is represented, 53% female, sample slightly biased towards higher education | Organic, fair-trade, Rainforest Alliance, and carbon footprint label | RED, SMI screen-based eye-tracker (120 Hz) [SensoMotoric Instruments, Teltow, Germany], high- resolution computer screen (22-inch), Experiment Suite 360°, and BeGaze software 3.0 | Choice experiment, eye-tracking, questionnaire | Fixation count, fixation duration | Sustainability criterions are more valued by consumers who spend more time attending to and fixating on them. Consumer preference increases when an organic label is on the coffee package. Consumers who place more value on sustainability aspects and/or price will also pay more attention to this information when making food choices. Sustainability aspects therefore attract a high degree of visual attention. Consumers who value sustainability aspects and visually pay more attention to sustainability information are also willing to pay more for sustainable products. |

| van Loo, E.J. et al., (2018) [58] | USA | Roasted ground coffee | 81 Each age and income category is represented, 53% female, sample slightly biased towards higher education | Organic, fair-trade, Rainforest Alliance, and carbon footprint label | RED, SMI screen-based eye-tracker (120 Hz) [SensoMotoric Instruments, Teltow, Germany], 56 cm computer screen (screen resolution 1680 × 1050 pixel), Experiment Suite 360°, and BeGaze software 3.0 | Choice experiment, eye-tracking | Fixation count | Consumers who don’t visually pay attention to sustainability logos are actually ignoring organic labels. Consumer preference increases when an organic logo is present on coffee packaging. |

| van Loo, E.J. et al., (2019) [59] | USA | Cheddar cheese | 103 At least 18 years of age, equal share of female and male, higher share of young and of higher educated participants, compared to general population, cheese consumer | Country-of-origin, region-of-origin, hormone-free, and biodegradable packaging label | Tobii X2-60 (60 Hz) [Tobii AB, Danderyd, Sweden], high-resolution computer screen, and Tobii Studio 2.2 software | Choice experiment, eye-tracking | Visit duration | Consumers pay attention to various attributes when selecting food. However, the country-of-origin label is the most attended label when choosing foods. |

| van Loo, E.J. et al., (2021) [60] | USA | Granola bar | 115 | Rainforest Alliance, fair-trade, non-GMO, and not genetically engineered label | Tobii X2-60 (60 Hz) [Tobii AB, Danderyd, Sweden], high-resolution computer screen, and Tobii Studio 3.4.5 software | Choice experiment, eye-tracking, questionnaire | Visit duration | Visual attention to sustainable claims influences product choice. Higher visual attention is associated with a higher likelihood of food choice. The higher the price, the less likely the consumer is to choose the sustainable food. When consumers focus (fixate) on an attribute for longer, this leads to a higher preference for that attribute. |

| Zhang, M.J. et al., (2023) [61] | China | Recycled water | 94 43 female and 51 male | Recyclable label | Tobii Pro Fusion (250 Hz) [Tobii AB, Danderyd, Sweden] | Eye-tracking, questionnaire | Fixation duration | The perceived benefit and quality of recycled water has a positive effect on the population’s willingness-to-purchase, while the perceived risk of recycled water influences the willingness-to-purchase negatively. The higher the visual attention to user comments, the more likely it is to stimulate and promote the public’s perceived usefulness of recycled water. |

| Categories | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age ranges | ||

| 18–30 years | 3 | 7.9 |

| 19–48 years | 3 | 7.9 |

| 18–59 years | 3 | 7.9 |

| 18–65 years | 11 | 28.9 |

| Not specified | 18 | 47.3 |

| University students | 9 | 23.7 |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 1.575 | 57.0 |

| Male | 1.193 | 43.0 |

| Sustainability Labels | % | Sustainability Labels | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Organic | 23.5 | Forest Stewardship Council | 1.2 |

| Country-of-origin | 8.2 | Free-range | 1.2 |

| Carbon footprint | 7.1 | Free-range (accredited) | 1.2 |

| Fair-trade | 7.1 | Friend of the Sea | 1.2 |

| Non-GMO, GMO-free | 4.7 | GGN certified aquaculture | 1.2 |

| Rainforest Alliance | 4.7 | Green products | 1.2 |

| Region-of-origin | 3.5 | Halal | 1.2 |

| Biodegradable packaging | 2.4 | Local | 1.2 |

| Hormone-free | 2.4 | Local farmer | 1.2 |

| Keyhole | 2.4 | Not genetically engineered | 1.2 |

| Recyclable | 2.4 | Nutrient content claim | 1.2 |

| 100% recycled paperboard | 1.2 | Pesticide-free | 1.2 |

| Animal feeding | 1.2 | PEFC | 1.2 |

| Antibiotic-free | 1.2 | Protected geographical indication | 1.2 |

| ASC | 1.2 | RSPC approved farming scheme | 1.2 |

| Bio | 1.2 | Sustainable Forestry Initiative | 1.2 |

| Certified coffee | 1.2 | Sustainable Irrigation | 1.2 |

| Certified Humane | 1.2 | Transitional certified by QAI | 1.2 |

| Dolphin Safe | 1.2 | Visually suboptimal food | 1.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ruppenthal, T. Eye-Tracking Studies on Sustainable Food Consumption: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16434. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152316434

Ruppenthal T. Eye-Tracking Studies on Sustainable Food Consumption: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability. 2023; 15(23):16434. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152316434

Chicago/Turabian StyleRuppenthal, Tonia. 2023. "Eye-Tracking Studies on Sustainable Food Consumption: A Systematic Literature Review" Sustainability 15, no. 23: 16434. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152316434

APA StyleRuppenthal, T. (2023). Eye-Tracking Studies on Sustainable Food Consumption: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability, 15(23), 16434. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152316434