The Cultural Heritage of Montilla and the Printing Press since the Modern Age: Its Evolution and Relationship with Graphic Engineering Boosting the SDGs

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Precursors and History of the Printing Press

2.2. The Printing Press in Spain and Its Expansion throughout the New World

2.3. The Arrival of the Printing Press in Andalusia

2.4. From the Industrial Revolution to the Present Time: Technical Improvements of the Printing Press

3. Methodology and Materials

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Approximation to a Typographic Workshop of the 17th Century through the Etching of Stradanus

4.2. The Printing Press in Montilla in the 17th Century—Curiosities

4.3. Evolution of the Printing Press in Montilla

5. Conclusions

- -

- Ensuring equal access for men and women (SDG 4.3 and 4.5);

- -

- Improving their professional, personal, and social skills for employment (SDGs 4.4 and 4.6); promoting sustainable development and sustainable lifestyles; and valuing how culture contributes to sustainable development (SDG 4.7)

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tenllado’s Private Archive (Córdoba, Spain), Folder 116, n.d.

- Alfaro López, H.G.; Lafaye, J. Albores de la Imprenta. El Libro en España y Portugal y sus Posesiones en Ultramar (Siglos XV y XVI). Investigación Bibliotecológica. Archiconomía, Bibliotecología e Información; University of La Rioja: Logroño, Spain, 2003; pp. 183–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Printing History Association. To Encourage the Study of Printing History. History of Printing Timeline. Available online: https://printinghistory.org/timeline/ (accessed on 9 October 2023).

- Olivere, A.S. Manual de la Tipografía Española. El Arte de la Imprenta; Librería de D. Eduardo Oliveres: Madrid, Spain, 1852; pp. 9–18, 46–48, 81, 179–180, 204–206, 225–230, 297. [Google Scholar]

- Velduque Ballarín, M.J. El Origen de la Imprenta: La Xilografía. La Imprenta de Gutenberg. Revista de Claseshistoria. 2011. Available online: http://www.claseshistoria.com/revista/2011/articulos/velduque-imprenta-origen.html (accessed on 10 December 2023).

- Petit, N. Les Incunables: Livres Imprimés au XVe Siècle. Bibliotèque National Françaises. L’aventure du Livre. Available online: https://essentiels.bnf.fr/fr/livres-et-ecritures/histoire-du-livre-occidental/586fe06a-d438-4788-b994-c5b78c61634e-invention-imprimerie-15e-siecle/article/7ae46426-2b55-4849-9ff5-a52d8a76e1a8-naissance-imprimerie-en-occident (accessed on 26 May 2023).

- Clair, C. Historia de la Imprenta en Europa; Ollero & Ramos: Madrid, Spain, 1998; p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Mann, C. The Gutenberg Revolution: How Printing Changed the Course of History; Transworld Publishers Ltd.: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Cervantes, M. Don Quijote de la Mancha; Ed. Alhambra: Madrid, Spain, 1979; p. 530. [Google Scholar]

- Barbour, R. Renaissance Science and Literature. Minerva 2006, 44, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González Sarasa Hernáez, S. Delimitación Conceptual y Problemas Terminológicos en Torno a una Tipología Editorial del Libro Impreso. Anales de Documentación. 2011. Available online: https://digitum.um.es/digitum/handle/10201/25189 (accessed on 10 December 2023).

- Viñes Millet, C. La Imprenta Andaluza en la Edad Moderna. Materiales Para el Estudio del Papel de la Iglesia en la Cultura de Andalucía; Chronica Nova; Revista de Historia Moderna de la Universidad de Granada: Granada, Spain, 1978; p. 182. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/descarga/articulo/253056.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2023).

- Barker, N. The invention of printing: Revolution within Revolution. Q. J. Libr. Congr. 1978, 35, 64–76. [Google Scholar]

- Castillejo Benavente, A. La Imprenta en Sevilla en el siglo XVI (1521–1600); Editorial Universidad de Córdoba y Universidad de Sevilla: Sevilla, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Vera, J.J.S. El Mecanismo del Arte de la Imprenta Para los Operarios que la Ejerzan; Imprenta de la Compañía: Madrid, Spain, 1822. [Google Scholar]

- Palacios, J.M. El Manual del Cajista. Comprende la Explicación de Todas las Operaciones del Arte de la Imprenta, y una Adición Gramatical Relativa á Dicho arte; Imprenta de Ducazcal y Compañía: Madrid, Spain, 1845. [Google Scholar]

- Consejo de la Hispanidad. Novísima Recopilación de las Leyes de España; Librería de D. Eduardo Oliveres: Madrid, Spain, 1805; Volume IV, pp. 122–123. [Google Scholar]

- Cavillon Giomi, J. La Difusión de la Prensa Andaluza en la España de Carlos IV (1789–1808). Cuadernos de Ilustración y Romanticismo. In Revista Digital del Grupo de Estudios del Siglo XVIII de la Universidad de Cádiz; Universidad de Cádiz: Cádiz, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohigas, P. El Libro Español; Editorial Gustavo Gili S.A.: Barcelona, Spain, 1965; pp. 249–272. [Google Scholar]

- Morán Reyes, A.A. “No hay término ni fin en hacer ni multiplicar libros”: Las casas de impresores y la diversificación de la cultura libresca durante el siglo XVII en la capital novohispane. Rev. Complut. Hist. Am. 2019, 45, 159–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez Márquez, C. La Impresión y el Comercio se Libros en la Sevilla del Quinientos; Universidad de Sevilla: Sevilla, Spain, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin, C. Los Cromberger: La Historia de una Imprenta del Siglo XVI en Sevilla y Méjico; Ediciones de Cultura Hispánica: Madrid, Spain, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Cisneros, J.M.V. La Imprenta en Córdoba, Ensayo Bibliográfico; Establecimiento Tipográfico Sucesores de Rivadeneyra: Madrid, Spain, 1900. [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez de Arellano, R. La Imprenta en Córdoba: Cartas Publicadas en el “Diario de Córdoba”. Sevilla. 1889. Available online: https://archive.org/details/AFA01546COR (accessed on 10 December 2023).

- Collantes Sánchez, C.M. El origen de la imprenta en Córdoba. Titivilus Int. J. Rare Books 2021, 7, 209–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CERIG, INO Grenoble EFPG; Coste, G. Imprimerie: La Revolution Numérique. 2005. Available online: http://cerig.pagora.grenoble-inp.fr/dossier/impression-numerique/page01.htm (accessed on 10 December 2023).

- Moran, J. Printing Presses. History and Development from the Fifteenth Century to Modern Times; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA; Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1973; pp. 49–90. Available online: https://books.google.es/books?id=N5O73Rde6UwC&printsec=frontcover&dq=intitle:Printing+intitle:Presses+inauthor:Moran&hl=en&sa=X&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false (accessed on 10 December 2023).

- Sung, K.M. Early 19th Century Parisian Publishing Culture. The Victory of the Novel and the Commercialization of Literature. J. Humanit. 2019, 109, 115–144. [Google Scholar]

- Hargrave, J. Disruptive Technological History: Papermaking to Digital Printing. J. Sch. Publ. 2013, 44, 221–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozcan, A. Examination of the printability parameters of IPA free offset printing. J. Graph. Eng. Des. 2017, 8, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintas-Froufe, E. Evolution of Advertising Communication in the Pre-war: Analysis of Federico Ribas Advertising Portfolio for Gal Fragrance House (1916–1936). Rev. Lat. Comun. Soc. 2012, 67, 430–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascales Salinas, B.; Lucas Saorín, P.; Mira Ros, J.M.; Pallarés Ruiz, A.; Sánchez-Pedreño Guillén, S. LATEX, Una Imprenta en sus Manos; Aula Documental de Investigación: Madrid, Spain, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Kottwitz, S. Latex. Create High-Quality and Professional-Looking Text, Articles and Books for Business and Science Using LaTeX; Packt Publishing: Birmingham, UK, 2021; pp. 35–36. [Google Scholar]

- Mussellini, C. Digital Publishing in Europe: A Focus on France, Germany, Italy and Spain. Publ. Res. Q. 2010, 26, 168–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skuta, P. Analysis of Interactive iPad Textbooks. AIP Conf. Proc. 2018, 2040, 030021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigarchian, H.G.; Logghe, S.; Verborgh, R.; Neve, W.; Salliau, F.; Mannens, E.; Van de Walle, R.; Schuurman, D. Hybrid e-TextBooks as comprehensive interactive learning enviroments. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2018, 26, 486–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, A.; Deuermeyer, E.; Nam, B.; Chu, S.L.; Queck, F. Exploring the 3D Printing Process for Young Children in Curriculum-Aligned Making in the Classroom. In Proceedings of the 2018 ACM Conference on Interaction Design and Children, Trondheim, Norway, 19–22 June 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geroni, P. Libraries, the long tail and the future of legacy print collections. Libr. Inf. Sci. Res. E-J. 2007, 17, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leionen, T.; Virnes, M.; Hietala, I.; Brinck, J. 3D Printing in the Wild: Adopting Digital Fabrication in Elementary School Education. Int. J. Art Des. Educ. 2020, 39, 600–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemorin, S.; Selwyn, N. Making the best of it? Exploring the realities of 3D printing in school. Res. Pap. Educ. 2017, 32, 578–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, W. The Effect of 3D Printing Technology on School Education. In International Symposium Modern Education and Human Sciences; MEHS: Zhangiajie, China, 2014; pp. 547–550. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, A.; Carrega, J.; D’Orey, R.; da Silva, B.M. From Pront to Pixels: Prototyping a Virtual Exhibition for the Faro Museum Poster Collection. In Advances in Design and Digital Communication IV, Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Design and Digital Communication, Digicom 2023, Barcelos, Portugal, 9–11 November 2023; Springer Series in Design and Innovation; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; Volume 35, pp. 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaimaris, D.; Patias, P.; Roustanis, T.; Poulopolus, K.; Faradimas, D. The Development of a Model System for the Visualization of Information on Cultural Activities and Events. Electronics 2023, 12, 4769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magadán, M.; Rivas-García, J. Driving variables of the Spanish publishing industry. Prof. Inf. 2018, 27, 1335–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magadán, M.; Rivas-García, J. Facing Innovation and Digitization: The Case of Spanish Printing Houses. Publ. Res. Q. 2021, 37, 168–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulten, P.; Viström, M.; Mejtolf, T. New printing technology and pricing. Sci. Direct Ind. Mark. Manag. 2009, 38, 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cauzzi, C.; De Francesca, V.; Longhi, L.; Viazzi, F. Librarians into the mirror: Meet the others to recognize ourselves. AIB Studi 2016, 52, 219–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manrique, A.; Morgado, A. Oficina de Tipo: Comparative Study of Wood Type Production Methods (CNC and Pantograph). In Advances in Design and Digital Communication IV, Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Design and Digital Communication, Digicom 2023, Barcelos, Portugal, 9–11 November 2023; Springer Series in Design and Innovation; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; Volume 35, pp. 459–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stradanus, I. Nova Reperta. Amberes; Phls Galle Escud. In Biblioteca Nacional de España, Biblioteca Digital Hispánica, (Sala Goya, Bellas Artes), ER/1605 MICROFILM P, 1000431280, p. 7. 1600. Available online: http://bdh-rd.bne.es/viewer.vm?id=0000223473 (accessed on 10 December 2023).

- Montes Balado, M.N. La Industria Agroalimentaria en la Pintura. Aplicación a los Grabados de Giovanni Stradanus; Universidad de Córdoba: Córdoba, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Montes Balado, N.; Porcuna Bermúdez, D.; Sanz Cabrera, J.; Sánchez-Pineda de las Infantas, M.T. Evolución de las almazaras en España desde la representada por Johannes Stradanus. Rev. DYNA 2019, 94, 513–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markey, L. Renaissance Invention. Stradanus’s Nova Reperta; Northwestern University Press: Evaston, IL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Fertel, M.D. La Science Pratique d l´Imprimerie. Contenant des Instrutions très-Faciles pour se Perfeccionner Dans cet art. Fertel: Saint Omer-M.D. 1723. Available online: https://books.google.bj/books?id=IwY_AAAAcAAJ&printsec=frontcover&hl=es&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false (accessed on 10 December 2023).

- La Lande, J. Arte de Hacer el Papel Según se Practica en Francia y Holanda, en la China y en el Japón; Pedro Marin: Madrid, Spain, 1778; pp. 136–141. [Google Scholar]

- De Franceschi, L. La storia della stampa vista da Elizabeth L. Eisenstein in Divine art, infernal machine. AIB Studi 2012, 52, 218–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintanilla Raso, M.C. Nobleza y Señoríos en el Reino de Córdoba. La Casa de Aguilar (Siglos XIV y XV); Publicaciones del Monte de Piedad y Caja de Ahorros de Córdoba: Córdoba, Spain, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Calvo Poyato, J. Guía Histórica de Montilla; Tipografía Católica: Córdoba, Spain, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Calvo Serrano, M.A. El Patrimonio Monumental de Montilla: Caso de la Parroquia de Santiago Apóstol; Universidad de Córdoba: Córdoba, Spain, 2020; pp. 1–38. Available online: https://helvia.uco.es/handle/10396/21273 (accessed on 10 December 2023).

- Morte Molina, J. Montilla: Apuntes Históricos de Esta Ciudad; Imprenta, Papelería y Encuadernación de M. de Sola Torices: Montilla, Spain, 1888; p. 179. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado Casado, J. Diccionario de Impresores Españoles: (Siglos XV–XVII); Arco Libros: Madrid, Spain, 1996; p. 474. [Google Scholar]

- Gascón Ricao, A. Los Tres Morales de Montilla. Juan Bautista de Morales, Cristóbal de Moral y Iuan de Morales, Hijo. En Cultura Sorda. Available online: https://cultura-sorda.org/los-tres-morales-de-montilla-juan-bautista-de-morales-cristobal-bautista-de-morales-y-iuan-bautista-de-morales-hijo/#_ftn2 (accessed on 10 December 2023).

- Parish Archive of Santiago de Montilla (A.P.S.M.), 5th Book of Christenings, f. 264v.

- Parish Archive of Santiago de Montilla (A.P.S.M.), 3rd Book of Wedding Bows, f. 2v.

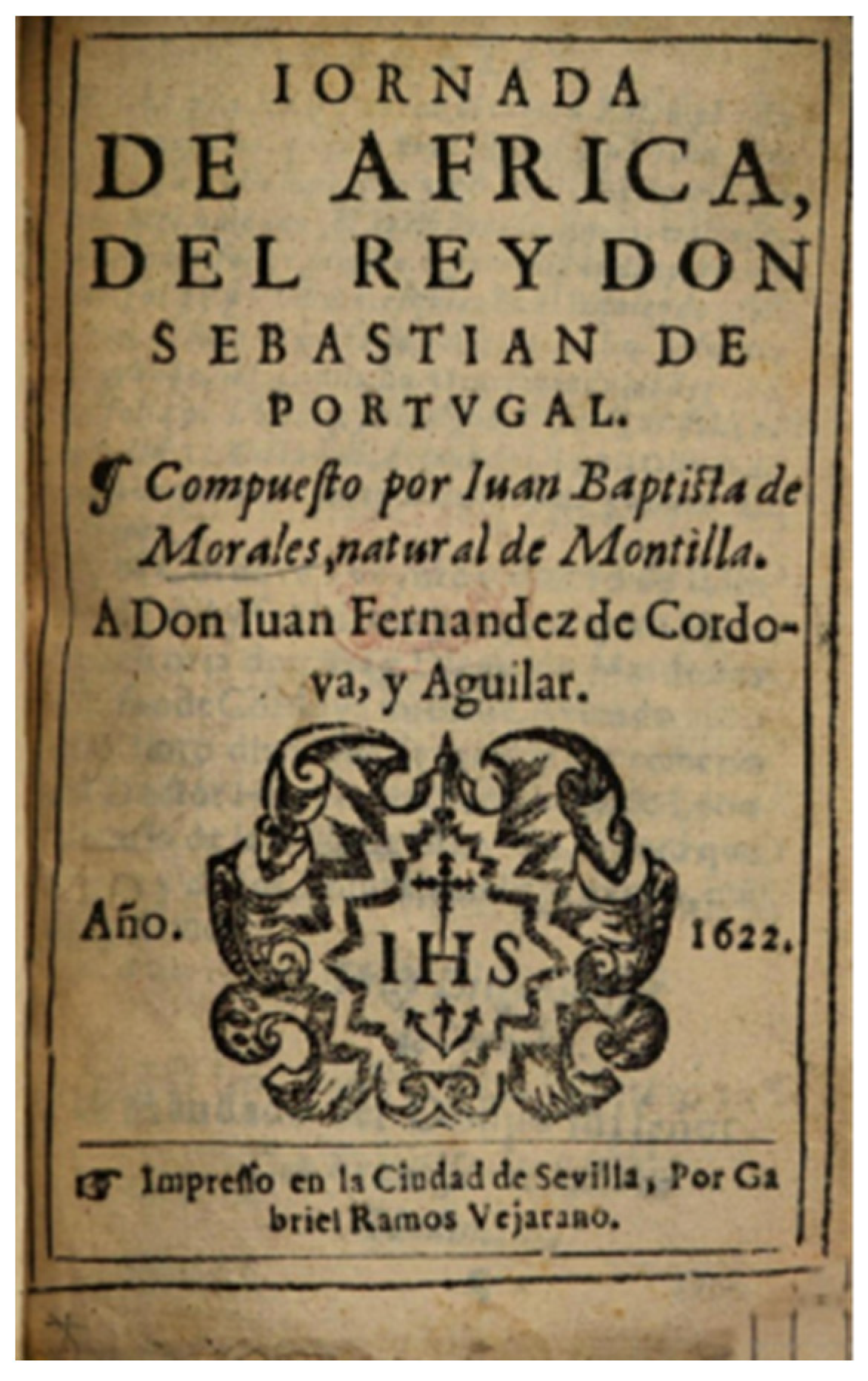

- Morales, J.B. Jornada de África del rey Don Sebastian de Portugal; Imp. Gabriel Ramos Vejarano: Sevilla, Spain, 1622; In Fundación Biblioteca Manuel Ruiz Luque (Montilla), Reg. 15394. [Google Scholar]

- Historical Archive of Notary Protocols of Montilla (A.H.P.N.M), 7th Notary, File 1185, f. 246.

- Peñalver Gómez, E. La Imprenta en Sevilla en el Siglo XVII; Universidad de Sevilla: Sevilla, Spain, 2019; p. 439. Available online: https://idus.us.es/handle/11441/89775 (accessed on 10 December 2023).

- Rodríguez Lobo, F. Corte en Aldea, y Noches de Invierno; Imprenta de Juan Bautista de Morales: Montilla, Spain, 1622; Available online: http://bdh-rd.bne.es/viewer.vm?id=0000080796&page=1 (accessed on 10 December 2023).

- González Ramírez, D. Corte en aldea (1622) de Rodrigues Lobo: Un manual de cortesanía portugués en su contexto español. Criticón 2018, 134, 211–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez de Cardona, M. Maravillas de la Naturaleza en que se Contienen Dos Mil Secretos de Cosas Naturales Dispuestos por Abecedario a Modo de Aforismos Recogidos de la Lección de Diversos y Graves Autores; Imprenta del Exmo.: Montilla, Spain, 1629; In Fundación Biblioteca Manuel Ruiz Luque (Montilla), Reg. 13714. [Google Scholar]

- Morales, C.B. Pronunciaciones Generales de Lenguas, Ortografía, Escuela de Leer, Escribir, y Contar, y Sinificacion de Letras en la Mano; Imprenta de Juan Bautista de Morales: Montilla, Spain, 1623; Available online: http://bdh.bne.es/bnesearch/detalle/bdh0000039726 (accessed on 10 December 2023).

- de Arriaga Joseph, F.G. Fiestas que Celebro la Noble Villa de Vaena a la Canonizacion de los Gloriosos Mártires del Japon; Imprenta del Exmo.: Montilla, Spain, 1624; In Fundación Biblioteca Manuel Ruiz Luque (Montilla), Reg. 13768. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro, P. Famosa Vitoria y Grandiosa Presa que Algunas Galeras de Napoles, Florencia y Sicilia Alcançaron de un Renegado Morisco Natural de Ossuna, General de ocho Galeras del Turco Miércoles Quatro de Otubre Dia de s. Francisco Deste Año de 1623; Pedro Navarro: Montilla, Spain, 1623; Available online: https://iberian.ucd.ie/view/iberian:32266 (accessed on 10 December 2023).

- Jiménez Barranco, A.L. Los Cinco Años de Manuel de Payva en Montilla. Perfiles Montillanos. 2010. Available online: https://perfilesmontillanos.blogspot.com/2010/11/ (accessed on 10 December 2023).

- Historical Archive of Notary Protocols of Montilla (A.H.P.N.M), 1st Desk, File 48, f. 211.

- Historical Archive of Notary Protocols of Montilla (A.H.P.N.M), 5th Desk, File 802, f.f. 277 and 492–495.

- Mendoza, F.V. Panegírico por la Poesía; Imprenta de Manuel de Payva: Montilla, Spain, 1627; In Fundación Biblioteca Manuel Ruiz Luque (Montilla), Reg. 15393. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado Moral, C. El Panegírico por la Poesía de Fernando de Vera y Mendoza en la Preceptiva Poético del Siglo de Oro. Córdoba; Universidad de Córdoba: Córdoba, Spain, 2013; p. 16. Available online: https://helvia.uco.es/xmlui/handle/10396/10879 (accessed on 10 December 2023).

- Domínguez Bordona, J. Memorial Dado por Juan Serrano de Bargas Maestro Impresor de Libros en Sevilla en Julio de 1625 Sobre los Excesos en Materia de Libros; Revista de Archivos, Bibliotecas y Museos, Cuerpo Facultativo de Archiveros, Bibliotecarios y Anticuarios: Madrid, Spain, 1926; pp. 224–227. [Google Scholar]

- Diario Córdoba de Comercio, Industria, Administración, Noticias y Avisos. Núm. 13, de 19 de Septiembre de 1888. In Biblioteca Virtual de Prensa Histórica. Available online: https://prensahistorica.mcu.es/es/catalogo_imagenes/grupo.do?path=2000843090 (accessed on 10 December 2023).

| Year | Book |

|---|---|

| 1622 | Corte en aldea y noches de imbierno (Village Court and Winter Nights) |

| 1623 | Pronunciaciones generales de lenguas, ortografía, escuela de leer, escribir, y contar, y sinificacion de latras en la mano (General Pronunciations of Languages, Grammar, Reading school, Writing, and Counting, and the Meaning of Hand-Written Letters) |

| 1623 | Copia de una carta que nuestro santissimo padre Gregorio Decimo Quinto escrivio al serenissimo rey de la Gran Bretaña (Copy of a Letter that our Holy Father Gregorio the Fifteenth wrote to His Serene Highness King of Great Britain) |

| 1623 | Respuesta del serenissimo príncipe de Gales a la carta de nuestro santissimo padre Gregorio XV (Reply of His Serene Highness Prince of Wales to the letter of our Father Gregorio the 15th) |

| 1624 | Declaracion de las prodigiosas señales del monstruoso pescado que se hallo en un rio de Polonia en Alemania cuyo retrato se embio a España este año de 1624 (Declaration of the Prodigious Signs of the Monstruous Fish Found in a River of Poland in Germany whose Portrait was sent to Spain this Year of 1624) |

| 1624 | Varios prodigios y prodigiosos monstruos que se an visto en el mundo. Y explicación de lo sinifican… (Several Marvels and Prodigious Monsters that have been seen in the World. And an Explanation of what they mean…) |

| 1624 | Viaje a Roma para el año santo del jubileo (Trip to Rome for the Holy Year of the Jubilee) |

| 1625 | Ramilletes de documentos christianos y avisos morales del caton christiano (Bundles of Christian Documents and Moral Warnings of the Christian Canon) |

| 1629 | Corte de aldea y noches de invierno (Village Court and Winter Nights) |

| 1629 | Traduccion de la Primavera (Translation of “Spring”) |

| 1631 | Chançonetas que canto la música de la catedral de Cordova en la fiesta del insigne altar que se dedico en 15 de enero de 1631 (Songs Sung by the Orchestra of Córdoba Cathedral in the Festivity of the Distinguished Altar on 15 January 1631) |

| 1633 | Semon que predico el dia del peraphico patriarca san Francisco en su convento dedicado al mismo glorioso sancto su padre (Speech Given by Patriarch San Francisco on Peraphico Day in his Monastery Dedicated to his Glorious Father) |

| 1633 | Memorial que envio a la santidad de nuestro santissimo padre Urbano VIII en orden a la canonización del santo rey don Fernando por la ciudad de Sevilla (Memorial sent to our Holy Father Urbano the Eighth for the Canonization of His Holy Highness King Fernando by the City of Seville) |

| Year | Book |

|---|---|

| 1626 | Relaciones. Copia de lo que se halla en las provanças hechas para la canoniçcacion del venerable padre maestro Juan de Avila, predicador apostólico destos reynos, y en particular de Andaluzia (Relationships. Copy of what is found in the Provinces made for the Canonization of the Venerable Father Juan de Avila, Apostolic Preacher of this Kingdom, Particularly Andalusia) |

| 1626 | Discurso en la confeccion de Alchermes (Discourse on the Making of Alchermes) |

| 1629 | Maravillas de la naturaleza en que se contienen dos mil secretos de cosas naturales dispuestos por abecedario a modo de aforismos recogidos de la lección de diversos y graves autores (Marvels of Nature, Containing Two Thousand Secrets of natural things ordered alphabetically as a list of aphorisms gathered from the teachings of diverse and important authors) |

| 1628 | Hermandad cristiana. Ermandad christiana en favor de vivos, y difundos, para librarse de las penas del purgatorio, alcançar con otros bienes de Dios n.s. en esta vida (Christian Brotherhood. Christian Brotherhood in favor of the living, and the dead, to avoid the sufferings of purgatory, attaining with other goods of God our Lord in this life) |

| 1631 | Primera parte del arte de servir a nuestra señora y entretenimiento para sus devotos (First part of serving Our Lady and entertainment for her devotees) |

| 1634 | Romances y chançonetas que se cantaron en la profession de doña Francisca de Cordona y Ribera hija de los marqueses de Priego y ahora soror Francisca de la Cruz y de los Angeles (Romances and songs that were sung in the profession of Mrs. Francisca de Cordona and Ribera, daughter of the Marquises of Priego and now sister Francisca de la Cross and the Angels) |

| 1634 | Fiestas que celebro la noble villa de Vaena a la canonizacion de los gloriosos mártires del Japon (Festivities that were celebrated in the noble small town of Vaena for the canonization of the glorious martyrs of Japan) |

| Year | Books |

|---|---|

| 1625 | Relacion del auto de fe celebrado en Sevilla en 30 de noviembre de 1624, dirigido a Miguel Alvarez Salvador, familiar del santo oficio y regidor perpetuo de la villa de Alcala de Guadaira (Report of the burning of a heretic in Seville on 30 November 1624, addressed to Miguel Alvarez Salvador, kin of the holy service and perpetual councilor of the small town of Alcala de Guadaira) |

| 1625 | Tratado y relación del auto publico de fee que se hizo en la ciudad de Sevilla el dia de san Andres, sábado 30 de noviembre, por mandado del santo oficio de la inquisición de la misma ciudad (Treatise and report of the public burning of a heretic in the city of Seville on San Andres Day, Saturday 30 November, ordered by the holy service of the Inquisition of that city) |

| 1625 | Verdadera relación de la grandiosa vitoria, que las armadas de España han tenido en las entradas de Brasil, la qual queda por el rey don Felipe Quarto. Dase también aviso de la refiega de los navios sobre la baia y los días que duraron las batallas (True report of the grandiose victory of the Spanish Armada in the entries of Brazil for our King Felipe the Fourth. It also includes the report of the battles of the ships on the bay and the days that they lasted) |

| 1625 | Apologia en defensa del padre maestro fran Fernando de Luxan. (Case in the defense of Father Fran Fernando de Luxan) |

| 1626 | Sermon predicado en la fiesta de la exaltación de la cruz y del sanctissimo sacramento de la eucaristhia, en la ciudad de Cordova. (Sermon preached in the festivity of the passion of the Cross and the holy sacrament of the eucharist, in the city of Córdoba) |

| 1626 | Discurso del doctor Lorenço de Samillan medico desta ciudad de Sevilla en que se tratan tres puntos tocantes a la curación del sarampión y viruelas, muy necesarios y por el consiguiente se tocan algunas questiones de no menos importancia. (Speech of Dr. Lorenço de Samillan, physician of the city of Seville, which tackles three points related to measles and smallpox, which are very necessary, and therefore, other matters of similar relevance are also approached) |

| 1627 | Panegyrico por la poesía (Panegyric for poetry) |

| Century | Printing Press |

|---|---|

| 17th | Juan Bautista de Morales |

| Manuel de Payua | |

| Printing Press of the Marquis of Priego | |

| 18th | ------- |

| 19th | Printing press of Garnelo |

| Printing press of Francisco de Paula Moreno | |

| Printing press of M. de Sola Torices | |

| El Progreso Typographic Establishment | |

| José Córdoba Aguilera Typographic Establishment | |

| La Campiña Printing Press | |

| 20th | Gave |

| Printing press of San José | |

| La Industria Printing Press | |

| Luis Raigón Printers | |

| La Española Printing Press | |

| La Gutenberg | |

| Montilla Agraria | |

| San Francisco Solano | |

| La Montillana | |

| Sarmiento | |

| XXI | Gave Graphic Arts |

| La Gutenberg Printing Press | |

| Servitalonario.com | |

| M.C. Graphic Printing Press |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rey-García, J.; Calvo-Serrano, M.-A.; Montes-Tubío, F.d.P.; Bellido-Vela, E.; Triviño-Tarradas, P. The Cultural Heritage of Montilla and the Printing Press since the Modern Age: Its Evolution and Relationship with Graphic Engineering Boosting the SDGs. Sustainability 2024, 16, 541. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16020541

Rey-García J, Calvo-Serrano M-A, Montes-Tubío FdP, Bellido-Vela E, Triviño-Tarradas P. The Cultural Heritage of Montilla and the Printing Press since the Modern Age: Its Evolution and Relationship with Graphic Engineering Boosting the SDGs. Sustainability. 2024; 16(2):541. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16020541

Chicago/Turabian StyleRey-García, José, María-Araceli Calvo-Serrano, Francisco de Paula Montes-Tubío, Elena Bellido-Vela, and Paula Triviño-Tarradas. 2024. "The Cultural Heritage of Montilla and the Printing Press since the Modern Age: Its Evolution and Relationship with Graphic Engineering Boosting the SDGs" Sustainability 16, no. 2: 541. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16020541