Recent Advances in Optical Sensing for the Detection of Microbial Contaminants

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Optical Sensing

2.1. Colorimetric Optical Sensors

2.2. Fluorescence Optical Sensors

2.3. Interferometric Optical Sensor

2.4. Plasmonic Optical Sensors

| Sensing Platform | Microbial Contaminant | Ligand | Sample | Concentration Range | LOD | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPR | Brucella melitensis | B70 aptamer | Milk | 102–106 CFU/mL | 27 ± 11 cells | [73] |

| SPR | L. monocytogenes | Wheat germ agglutinin | Milk | 1–8 log CFU/100 μL | 3.25 log CFU/100 μL | [31] |

| SPR | E. coli | Polyclonal antibodies | Milk | 105–108 CFU/mL | 6.3 × 104 cells | [74] |

| SPR | E. coli O157:H7 Salmonella enteritidis, L. monocytogenes | Polyclonal antibodies | Chicken | 106 CFU/mL | 14 CFU/25 mL, 6 CFU/25 mL, 28 CFU/25 mL | [75] |

| SPR | Endotoxin | - | LAL test reagent | 50–0.0005 EU/mL | <0.0005 EU/mL | [76] |

| SPR | E. coli | Antibodies | Aqueous solution | 3.8 × 106 to 9.76 × 108 CFU/mL | 1.1 × 106 CFU/mL | [77] |

| LSPR | S. aureus | Aptamer | Milk | 103–108 CFU/mL | 103 CFU/mL | [78] |

| LSPR | E. coli O157:H7 | Antibodies | Fresh lettuce | 101–106 cell/mL | 10 cell/mL | [79] |

| LSPR | E. coli O157:H7 | Antibodies | Aqueous solution | 101–105 CFU/mL | 10 CFU/mL | [80] |

| LSPR | E. coli O157:H7 | Antibodies | Aqueous solution | 101–105 CFU/mL | 10 CFU/mL | [81] |

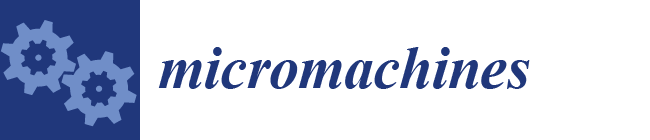

2.5. Raman Spectroscopy

3. Material Used for Optical Sensing Platforms

3.1. Nanomaterial-Based Optical Sensing

| Composite Nanomaterial | Sensing Platform | Microbial Contaminant | Concentration Range | LOD | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Au NPs/Silica NPs | LSPR | Lactobacillus acidophilus, S. typhimurium, Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 104–1012 CFU/L | 104 CFU/L | [98] |

| MnO2 Nanoflowers/QDs | Fluorescent immunoassay | E. coli, S. typhimurium. | 1.5 × 101–1.5 × 106 CFU/mL, 4 × 101–4 × 106 CFU/mL | 15 CFU/mL, 4 CFU/mL | [99] |

| CDs/MNPs | Fluorescent detection | E. coli, S. aureus | 102–103 CFU/mL | 3.5 × 102 CFU/mL 3 × 102 CFU/mL | [100] |

| GO/QDs | Photoluminescent Lateral-Flow Immunoassay | E. coli | 10 CFU/mL (standard buffer) 100 CFU/mL (bottled water and milk) | 2–105 CFU/mL | [101] |

| Ag/ZnO/rGO | SERS | E. coli | 5 × 104–5 × 108 CFU/mL | 104 CFU/mL | [102] |

| Ag NPs/rGO | SERS | E. coli | 1 × 105–2 × 108 CFU/mL | 1 × 105 CFU/mL | [103] |

| Au@Ag NP | SERS | S. typhimurium | 101–105 cells/mL | 15 CFU/mL | [104] |

| CDs-microspheres | Fluorescent immunoassay | E. coli O157:H7 | 2.4 × 102–2.4 × 107 CFU/mL | 2.4 × 107 CFU/mL | [105] |

| NBs/GNRs | SERS aptasensor | E. coli O157:H7 | 10–10,000 CFU/mL | 3 CFU/mL | [106] |

| Dual-functional metal complex- AuNPs | SERS aptasensor | Shigella sonnei | 10–106 CFU/mL | 10 CFU/mL | [107] |

| GQDs/GO | FRET immunosensor | Campylobacter jejuni | 10–106 cell/mL | 10 cell/mL | [108] |

| CQDs-MNPs | Fluorescent aptasensor | E. coli O157:H7 | 500–106 CFU/mL | 487 CFU/mL | [109] |

| Rhodamine B modified silica NP | Fluorescent assay | E. coli | 10–105 CFU/mL | 8 CFU/mL | [110] |

3.1.1. Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs)

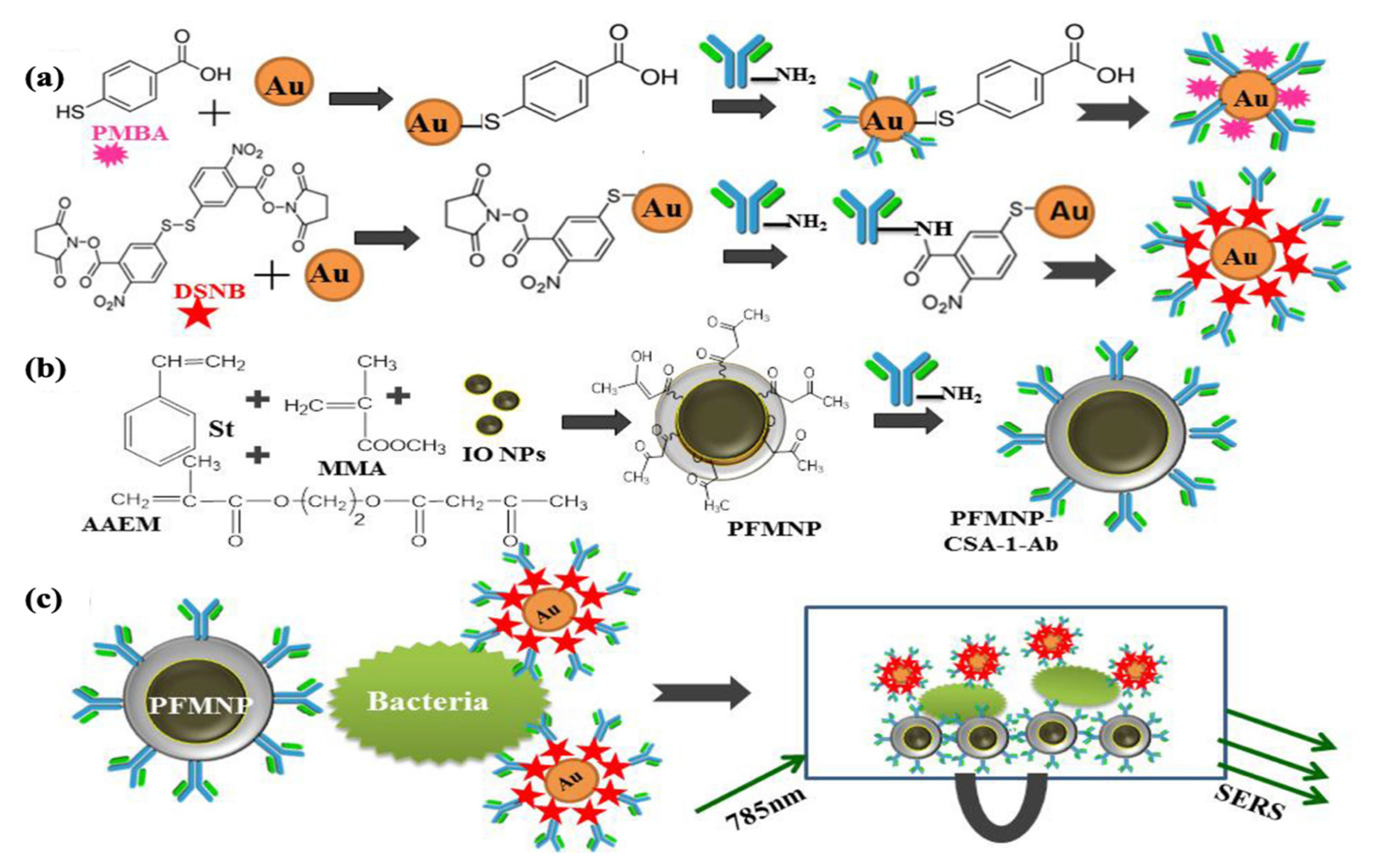

3.1.2. Magnetic Nanoparticles (MNPs)

3.1.3. Quantum Dots (QDs)

3.1.4. Carbon Nanomaterials

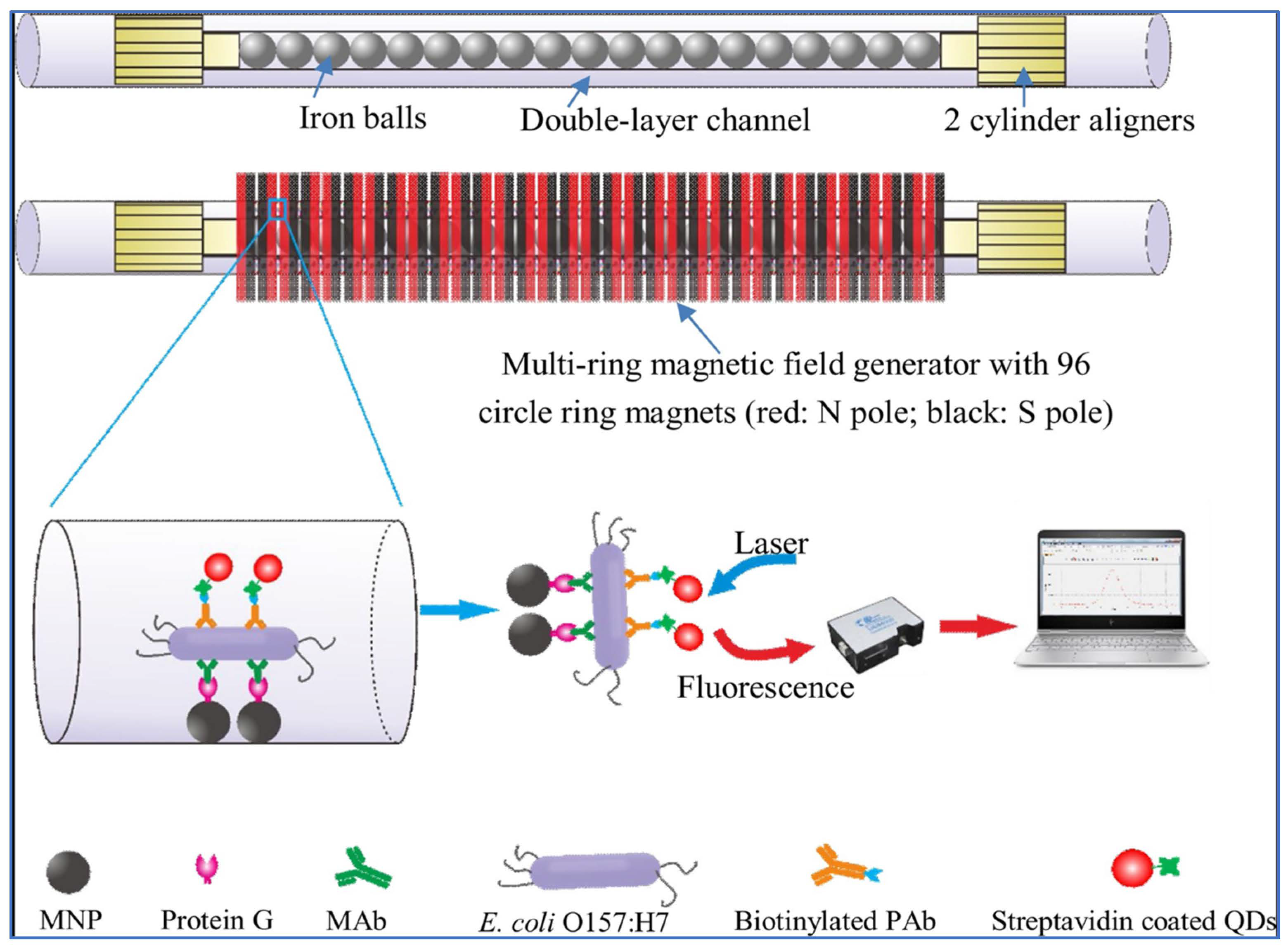

3.2. Molecular Imprinting-Based Optical Sensing

3.3. Hydrogel-Based Optical Sensing

4. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AAEM | Acetoacetoxy ethyl methacrylate |

| AFB 1 | Aflatoxin B 1 |

| AFM | Atomic force microscope |

| AIBN | Azobisisobutyronitrile |

| AuNPs | Gold nanoparticles |

| cApt | Complementary aptamer |

| CDs | Carbon dots |

| CFU | Colony forming unit |

| DSNB | 5,5′-dithiobis succinimidyl-2-nitrobenzoate |

| EGDMA | Ethylene glycol dimethylacrylate |

| ELISA | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| FMSs | Polyclonal antibody-modified microspheres |

| FRET | Fluorescence resonance energy transfer |

| GNRs | Gold nanorods |

| GO | Graphene oxide |

| HEMA | 2-Hydroxyethyl methacrylate |

| LAMP | loop-mediated isothermal amplification |

| LOD | Limit of detection |

| LOQ | The limit of quantification |

| LSPR | Localized surface plasmon resonance |

| MAH | N-methacryloyl-L-histidine methyl ester |

| MAPA | N-methacryl-(L)-phenylalanine |

| MBA | 4-mercapto benzoic acid |

| MC-LR | Microcystin-LR |

| MIP | Molecularly imprinted polymer |

| MMA | Methyl methacrylate |

| MNPs | Magnetic nanoparticles |

| MPA | 3-mercaptopropionic acid |

| NBs | Nanobones |

| NPs | Nanoparticles |

| OTA | Ochratoxin A |

| OTS | Octadecyltrichlorosilanes |

| PFMNPs | Polymeric magnetic nanoparticles |

| PLS-DA | Partial least squares discriminant analysis |

| pNIPAM | poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) |

| POC | Point-of-care |

| QDs | Quantum dots |

| rGO | Reduced graphene oxide |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscope |

| SERS | Surface enhanced Raman scattering |

| SPR | Surface plasmon resonance |

| St | Styrene |

| TMB | 3,5,3′,5′ tetramethyl benzidine |

| UFOB | U-bent fiber optic probe |

References

- Serwecinska, L. Antimicrobials and antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Water 2020, 12, 3313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doron, S. Bacterial Infections: Overview. Int. Encycl. Public Health 2020, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbashir, S.; Parveen, S.; Schwarz, J.; Rippen, T.; Jahncke, M.; DePaola, A. Seafood pathogens and information on antimicrobial resistance: A review. Food Microbiol. 2018, 70, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picciotti, U.; Dalbon, V.A.; Ciancio, A.; Colagiero, M.; Cozzi, G.; De Bellis, L.; Finetti-sialer, M.M.; Greco, D.; Ippolito, A.; Lahbib, N.; et al. “Ectomosphere”: Insects and Microorganism Interactions. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geletu, U.S.; Usmael, M.A.; Ibrahim, A.M. Isolation, identification, and susceptibility profile of E. coli, Salmonella, and S. aureus in dairy farm and their public health implication in Central Ethiopia. Vet. Med. Int. 2022, 2022, 887977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, L.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, Z. Antimicrobial resistance of pathogens causing nosocomial bloodstream infection in Hubei Province, China, from 2014 to 2016: A multicenter retrospective study. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fusco, V.; Abriouel, H.; Benomar, N.; Kabisch, J.; Chieffi, D.; Cho, G.-S.; Franz, C.M.A.P. Opportunistic Food-Borne Pathogens. In Food Safety and Preservation; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; ISBN 9780128149560. [Google Scholar]

- Llor, C.; Bjerrum, L. Antimicrobial resistance: Risk associated with antibiotic overuse and initiatives to reduce the problem. Ther. Adv. Drug Saf. 2014, 5, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sekoni, K.F.; Oreagba, I.A.; Oladoja, F.A. Antibiotic utilization study in a teaching hospital in Nigeria. JAC-Antimicrob. Resist. 2022, 4, dlac093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maragakis, L.L.; Perencevich, E.N.; Cosgrove, S.E. Clinical and economic burden of antimicrobial resistance. Expert Rev. Anti-Infect. Ther. 2014, 6, 751–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, C.J.; Ikuta, K.S.; Sharara, F.; Swetschinski, L.; Robles Aguilar, G.; Gray, A.; Han, C.; Bisignano, C.; Rao, P.; Wool, E.; et al. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: A systematic analysis. Lancet 2022, 399, 629–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadgostar, P. Antimicrobial resistance: Implications and costs. Infect. Drug Resist. 2019, 12, 3903–3910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gizaw, Z. Public health risks related to food safety issues in the food market: A systematic literature review. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2019, 24, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhalla, T.C.; Monika; Sheetal; Savitri. International Laws and Food-Borne Illness. In Food Safety and Human Health; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; ISBN 9780128163337. [Google Scholar]

- Todd, E.C.D. Foodborne diseases: Overview of biological hazards and foodborne diseases. Encycl. Food Saf. 2014, 1, 221–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bantawa, K.; Sah, S.N.; Subba Limbu, D.; Subba, P.; Ghimire, A. Antibiotic resistance patterns of Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, Salmonella, Shigella and Vibrio isolated from chicken, pork, buffalo and goat meat in eastern Nepal. BMC Res. Notes 2019, 12, 766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Castillo, F.Y.; Loera-Muro, A.; Jacques, M.; Garneau, P.; Avelar-González, F.J.; Harel, J.; Guerrero-Barrera, A.L. Waterborne pathogens: Detection methods and challenges. Pathogens 2015, 4, 307–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seboka, B.T.; Hailegebreal, S.; Yehualashet, D.E.; Kabthymer, R.H.; Negas, B.; Kanno, G.G.; Tesfa, G.A.; Yasmin, F. Methods used in the spatial analysis of diarrhea: A protocol for a systematic review. Med. Case Rep. Study Protoc. 2022, 3, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, J.; Wong, L.P.; Chua, Y.P.; Channa, N.; Mahar, R.B.; Yasmin, A.; Vanderslice, J.A.; Garn, J.V. Quantitative microbial risk assessment of drinking water quality to predict the risk of waterborne diseases in primary-school children. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nnachi, R.C.; Sui, N.; Ke, B.; Luo, Z.; Bhalla, N.; He, D.; Yang, Z. Biosensors for rapid detection of bacterial pathogens in water, food and environment. Environ. Int. 2022, 166, 107357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lobnik, A.; Turel, M.; Korent, S. Optical chemical sensors: Design and applications. In Advances in Chemical Sensors; BoD–Books on Demand: Paris, France, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mocan, T.; Matea, C.T.; Pop, T.; Mosteanu, O.; Buzoianu, A.D.; Puia, C.; Iancu, C.; Mocan, L. Development of nanoparticle-based optical sensors for pathogenic bacterial detection. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2017, 15, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Kumar, V.; Dhanjal, D.S.; Datta, S.; Prasad, R.; Singh, J. Biological biosensors for monitoring and diagnosis. In Microbial Biotechnology: Basic Research and Applications; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 317–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poltronieri, P.; Mezzolla, V.; Primiceri, E.; Maruccio, G. Biosensors for the detection of food pathogens. Foods 2014, 3, 511–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pebdeni, A.B.; Roshani, A.; Mirsadoughi, E.; Behzadifar, S.; Hosseini, M. Recent advances in optical biosensors for specific detection of E. coli bacteria in food and water. Food Control 2022, 135, 108822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, J.; Schanzle, J.A.; Tabacco, M.B. Real-time detection of bacterial contamination in dynamic aqueous environments using optical sensors. Anal. Chem. 2004, 76, 1411–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Sheng, B.; Peng, L.; Huang, Y.; Ni, Z. Flexible and optical fiber sensors composited by graphene and PDMS for motion detection. Polymers 2019, 11, 1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, T.; Zheng, Z.; Guo, K.; Zhao, J.; Dai, Q.; Li, H.; Pons-Moll, G.; Liu, Y. DoubleFusion: Real-Time Capture of Human Performances with Inner Body Shapes From a Single Depth Sensor. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 7287–7296. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, M.; Huang, K.; Xu, W. Ultrasensitive magnetic DNAzyme-copper nanoclusters fluorescent biosensor with triple amplification for the visual detection of E. coli O157:H7. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2020, 167, 112475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masdor, N.A.; Altintas, Z.; Shukor, M.Y.; Tothill, I.E. Subtractive inhibition assay for the detection of Campylobacter jejuni in chicken samples using surface plasmon resonance. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 13642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghu, H.V.; Kumar, N. Rapid Detection of Listeria monocytogenes in Milk by Surface Plasmon Resonance Using Wheat Germ Agglutinin. Food Anal. Methods 2020, 13, 982–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.A.; DeGrasse, J.A.; Yakes, B.J.; Croley, T.R. Rapid and sensitive detection of cholera toxin using gold nanoparticle-based simple colorimetric and dynamic light scattering assay. Anal. Chim. Acta 2015, 892, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torun, Ö.; Hakki Boyaci, I.; Temür, E.; Tamer, U. Comparison of sensing strategies in SPR biosensor for rapid and sensitive enumeration of bacteria. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2012, 37, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guven, B.; Basaran-Akgul, N.; Temur, E.; Tamer, U.; Boyaci, I.H. SERS-based sandwich immunoassay using antibody coated magnetic nanoparticles for Escherichia coli enumeration. Analyst 2011, 136, 740–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Sun, H.; Yang, W.; Fang, Y. Optical methods for label-free detection of bacteria. Biosensors 2022, 12, 1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, M.D.P.; Yamada-Ogatta, S.F.; Teixeira Tarley, C.R. Electrochemical and Bioelectrochemical Sensing Platforms for Diagnostics of COVID-19. Biosensors 2023, 13, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.Z.; Liu, Q.A.; Liu, Y.L.; Weng, G.J.; Zhu, J.; Li, J.J. Recent progress in the optical detection of pathogenic bacteria based on noble metal nanoparticles. Microchim. Acta 2021, 188, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebralidze, I.I.; Laschuk, N.O.; Poisson, J.; Zenkina, O.V. Colorimetric Sensors and Sensor Arrays. Nanomater. Des. Sens. Appl. 2019, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.D.; Lv, C.H.; Yuan, X.L.; He, M.; Lai, J.P.; Sun, H. A novel fluorescent optical fiber sensor for highly selective detection of antibiotic ciprofloxacin based on replaceable molecularly imprinted nanoparticles composite hydrogel detector. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2021, 328, 129000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkin, T.; Dave, D.P.; Milner, T.E.; Rylander, H.G., III. Interferometric fiber-based optical biosensor to measure ultra-small changes in refractive index. In Optical Fibers and Sensors for Medical Applications II, Proceedings of the International Symposium on Biomedical Optics, San Jose, CA, USA, 22–23 January 2002; SPIE: Cergy, France, 2002; Volume 4616, pp. 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perçin, I.; Idil, N.; Bakhshpour, M.; Yılmaz, E.; Mattiasson, B.; Denizli, A. Microcontact imprinted plasmonic nanosensors: Powerful tools in the detection of salmonella paratyphi. Sensors 2017, 17, 1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, C.S.; Jean, N.; Hogan, C.A.; Blackmon, L.; Jeffrey, S.S.; Holodniy, M.; Banaei, N.; Saleh, A.A.E.; Ermon, S.; Dionne, J. Rapid identification of pathogenic bacteria using Raman spectroscopy and deep learning. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chattopadhyay, S.; Sabharwal, P.K.; Jain, S.; Kaur, A.; Singh, H. Functionalized polymeric magnetic nanoparticle assisted SERS immunosensor for the sensitive detection of S. typhimurium. Anal. Chim. Acta 2019, 1067, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, O.S.; Bedwell, T.S.; Esen, C.; Garcia-Cruz, A.; Piletsky, S.A. Molecularly imprinted polymers in electrochemical and optical sensors. Trends Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 294–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.; Rushworth, J.V.; Hirst, N.A.; Millner, P.A. Biosensors for whole-cell bacterial detection. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2014, 27, 631–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.T.; Lee, Y.C.; Lai, Y.H.; Lim, J.C.; Huang, N.T.; Lin, C.T.; Huang, J.J. Review of integrated optical biosensors for point-of-care applications. Biosensors 2020, 10, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauriz, E. Clinical applications of visual plasmonic colorimetric sensing. Sensors 2020, 20, 6214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kandasamy, K.; Jannatin, M.; Chen, Y.C. Rapid detection of pathogenic bacteria by the naked eye. Biosensors 2021, 11, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, G.; Lu, M.; Huang, X.; Li, T.; Xu, D. Application of gold-nanoparticle colorimetric sensing to rapid food safety screening. Sensors 2018, 18, 4166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, L.; Li, N. Noble metal nanoparticles-based colorimetric biosensor for visual quantification: A mini review. Chemosensors 2019, 7, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Duan, N.; Qiu, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, Z. Colorimetric aptasensor for the detection of Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium using ZnFe2O4-reduced graphene oxide nanostructures as an effective peroxidase mimetics. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2017, 261, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suaifan, G.A.R.Y.; Alhogail, S.; Zourob, M. Rapid and low-cost biosensor for the detection of Staphylococcus aureus. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2017, 90, 230–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, B.; Kumar, S.; Kaushik, B.K. Trends, challenges, and advances in optical sensing for pathogenic bacteria detection (PathoBactD). Biosens. Bioelectron. X 2023, 14, 100352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.A.; Park, S.Y.; Cha, Y.; Gopala, L.; Lee, M.H. Strategies of Detecting Bacteria Using Fluorescence-Based Dyes. Front. Chem. 2021, 9, 743923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elahi, N.; Kamali, M.; Baghersad, M.H.; Amini, B. A fluorescence Nano-biosensors immobilization on Iron (MNPs) and gold (AuNPs) nanoparticles for detection of Shigella spp. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2019, 105, 110113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pathak, A.; Venugopal, P.; Nair, B.G.; Suneesh, P.V.; Satheesh Babu, T.G. Facile pH-sensitive optical detection of pathogenic bacteria and cell imaging using multi-emissive nitrogen-doped carbon dots. Microchem. J. 2020, 159, 105324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahari, D.; Babamiri, B.; Salimi, A.; Salimizand, H. Ratiometric fluorescence resonance energy transfer aptasensor for highly sensitive and selective detection of Acinetobacter baumannii bacteria in urine sample using carbon dots as optical nanoprobes. Talanta 2021, 221, 121619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, A.P.F.; Zourob, M.; Turner, A. Principles of Bacterial Detection: Biosensors, Recognition Receptors and Microsystems; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, F.; Chang, T.L.; Liu, T.; Wu, D.; Du, H.; Liang, J.; Tian, F. Label-free detection of Staphylococcus aureus bacteria using long-period fiber gratings with functional polyelectrolyte coatings. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2019, 133, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janik, M.; Brzozowska, E.; Czyszczoń, P.; Celebańska, A.; Koba, M.; Gamian, A.; Bock, W.J.; Śmietana, M. Optical fiber aptasensor for label-free bacteria detection in small volumes. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2021, 330, 129316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudak, F.C.; Boyaci, I.H. Rapid and label-free bacteria detection by surface plasmon resonance (SPR) biosensors. Biotechnol. J. 2009, 4, 1003–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asir, S.; Bakhshpour, M.; Unal, S.; Denizli, A. Nanoparticle-based plasmonic devices for bacteria and virus recognition. Mod. Pract. Healthc. Issues Biomed. Instrum. 2022, 167–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Zeng, X.; Liang, J. Surface plasmon resonance: An introduction to a surface spectroscopy technique. J. Chem. Educ. 2010, 87, 742–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Knoll, W.; Dostalek, J. Bacterial pathogen surface plasmon resonance biosensor advanced by long range surface plasmons and magnetic nanoparticle assays. Anal. Chem. 2012, 84, 8345–8350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, P.; Fatehbasharzad, P.; Colombo, M.; Fiandra, L.; Prosperi, D. Multifunctional magnetic gold nanomaterials for cancer. Trends Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 995–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaya, H.O.; Cetin, A.E.; Azimzadeh, M.; Topkaya, S.N. Pathogen detection with electrochemical biosensors: Advantages, challenges and future perspectives. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2021, 882, 114989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Singh, R.; Wang, Y.; Marques, C.; Zhang, B.; Kumar, S. Advances in novel nanomaterial-based optical fiber biosensors—A review. Biosensors 2022, 12, 843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waswa, J.; Irudayaraj, J.; DebRoy, C. Direct detection of E. coli O157:H7 in selected food systems by a surface plasmon resonance biosensor. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2007, 40, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemburu, S.; Wilkins, E.; Abdel-Hamid, I. Detection of pathogenic bacteria in food samples using highly-dispersed carbon particles. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2005, 21, 491–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petryayeva, E.; Krull, U.J. Localized surface plasmon resonance: Nanostructures, bioassays and biosensing—A review. Anal. Chim. Acta 2011, 706, 8–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellas, V.; Hu, D.; Mazouzi, Y.; Mimoun, Y.; Blanchard, J.; Guibert, C.; Salmain, M.; Boujday, S. Gold nanorods for LSPR biosensing: Synthesis, coating by silica, and bioanalytical applications. Biosensors 2020, 10, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, S.Y.; Heo, N.S.; Bajpai, V.K.; Jang, S.C.; Ok, G.; Cho, Y.; Huh, Y.S. Development of a cuvette-based LSPR sensor chip using a plasmonically active Transparent Strip. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2019, 7, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dursun, A.D.; Borsa, B.A.; Bayramoglu, G.; Arica, M.Y.; Ozalp, V.C. Surface plasmon resonance aptasensor for Brucella detection in milk. Talanta 2022, 239, 123074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamasaki, T.; Miyake, S.; Nakano, S.; Morimura, H.; Hirakawa, Y.; Nagao, M.; Iijima, Y.; Narita, H.; Ichiyama, S. Development of a surface plasmon resonance-based immunosensor for detection of 10 major O-Antigens on shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli, with a gel displacement technique to remove bound bacteria. Anal. Chem. 2016, 88, 6711–6717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Tsuji, S.; Kitaoka, H.; Kobayashi, H.; Tamai, M.; Honjoh, K.I.; Miyamoto, T. Simultaneous detection of Escherichia coli O157:H7, Salmonella enteritidis, and Listeria monocytogenes at a very low level using simultaneous enrichment broth and multichannel SPR biosensor. J. Food Sci. 2017, 82, 2357–2363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akimov, N.; Scudder, J.; Ye, J.Y. Refinement of an open-microcavity optical biosensor for bacterial endotoxin test. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2021, 191, 113436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakano, S.; Nagao, M.; Yamasaki, T.; Morimura, H.; Hama, N.; Iijima, Y.; Shinomiya, H.; Tanaka, M.; Yamamoto, M.; Matsumura, Y.; et al. Evaluation of a surface plasmon resonance imaging-based multiplex O-antigen serogrouping for Escherichia coli using eleven major serotypes of Shiga-toxin-producing E. coli. J. Infect. Chemother. 2018, 24, 443–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khateb, H.; Klös, G.; Meyer, R.L.; Sutherland, D.S. Development of a label-free LSPR-apta sensor for Staphylococcus aureus detection. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2020, 3, 3066–3077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, N.; Choi, S.W.; Chang, H.J.; Chun, H.S. Rapid detection of Escherichia coli O157:H7 in fresh lettuce based on Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance combined with immunomagnetic separation. J. Food Prot. 2018, 81, 713–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaghubi, F.; Zeinoddini, M.; Saeedinia, A.R.; Azizi, A.; Samimi Nemati, A. Design of Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance (LSPR) biosensor for immunodiagnostic of E. coli O157:H7 using gold nanoparticles conjugated to the chicken antibody. Plasmonics 2020, 15, 1481–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L.; Zhang, L.; Huang, Y.; Chen, L.; Zhang, G.; Shen, Z.; Zhang, J.; Xiao, Z.; Chen, T. Amplifying the signal of localized surface plasmon resonance sensing for the sensitive detection of Escherichia coli O157:H7. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 3288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Liu, W.; Tang, J.; Wang, J.; Liu, Q.; Wen, P.; Wang, M.; Pan, Y.; Gu, B.; Zhang, X. Applications of Raman Spectroscopy in bacterial infections: Principles, advantages, and shortcomings. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 683580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bräuer, B.; Thier, F.; Bittermann, M.; Baurecht, D.; Lieberzeit, P.A. Raman studies on surface-imprinted polymers to distinguish the polymer surface, imprints, and different bacteria. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2022, 5, 160–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Hu, Q.; Li, C.; Zhang, F.; Gu, H.; Wang, X.; Li, S.; Xue, L.; Madl, T.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Wide-range, rapid, and specific identification of pathogenic bacteria by Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy. ACS Sens. 2021, 6, 2911–2919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saletnik, A.; Saletnik, B.; Puchalski, C. Overview of popular techniques of raman spectroscopy and their potential in the study of plant tissues. Molecules 2021, 26, 1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Jiménez, A.I.; Lyu, D.; Lu, Z.; Liu, G.; Ren, B. Surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy: Benefits, trade-offs and future developments. Chem. Sci. 2020, 11, 4563–4577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jans, H.; Huo, Q. Gold nanoparticle-enabled biological and chemical detection and analysis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2023; advance article. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Hu, Z.; Yang, D.; Xie, S.; Jiang, Z.; Niessner, R.; Haisch, C.; Zhou, H.; Sun, P. Bacteria detection: From powerful SERS to its advanced compatible techniques. Adv. Sci. 2020, 7, 202001739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thvenot, D.R.; Toth, K.; Durst, R.A.; Wilson, G.S. Electrochemical biosensors: Recommended definitions and classification (Technical Report). Pure Appl. Chem. 1999, 71, 2333–2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sau, T.K.; Rogach, A.L.; Jäckel, F.; Klar, T.A.; Feldmann, J. Properties and Applications of Colloidal Nonspherical Noble Metal Nanoparticles. Adv. Mater. 2010, 22, 1805–1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moores, A.; Goettmann, F. The plasmon band in noble metal nanoparticles: An introduction to theory and applications. New J. Chem. 2006, 30, 1121–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, F.; Yang, Y.; Xie, X.; Wang, L.; Deng, K.; Xia, X.; Yang, X.; Huang, H. Prompting peroxidase-like activity of gold nanorod composites by localized surface plasmon resonance for fast colorimetric detection of prostate specific antigen. Analyst 2018, 143, 5038–5045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malekzad, H.; Sahandi Zangabad, P.; Mirshekari, H.; Karimi, M.; Hamblin, M.R. Noble metal nanoparticles in biosensors: Recent studies and applications. Nanotechnol. Rev. 2017, 6, 301–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Rao, H.; Luo, M.; Xue, X.; Xue, Z.; Lu, X. Noble metal nanoparticles growth-based colorimetric strategies: From monocolorimetric to multicolorimetric sensors. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2019, 398, 113003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivakumar, R.; Dinh, V.P.; Lee, N.Y. Ultraviolet-induced in situ gold nanoparticles for point-of-care testing of infectious diseases in loop-mediated isothermal amplification. Lab Chip 2021, 21, 700–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, H.; Kuča, K.; Bhatia, S.K.; Saini, K.; Kaushal, A.; Verma, R.; Bhalla, T.C.; Kumar, D. Applications of Nanotechnology in Sensor-Based Detection of Foodborne Pathogens. Sensors 2020, 20, 1966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Q.; Wu, W. Nanomaterial-based optical biosensors for the detection of foodborne bacteria. Food Rev. Int. 2020, 38, 655–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, S.M.; Kim, D.K.; Lee, S.Y. Aptamer-functionalized localized surface plasmon resonance sensor for the multiplexed detection of different bacterial species. Talanta 2015, 132, 112–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Zhou, X.; Luan, Y.; Cao, Y.; Wang, N.; Lu, Y.; Liu, T.; Xu, W. A sensitive electrochemical sensor modified with multi-walled carbon nanotubes doped molecularly imprinted silica nanospheres for detecting chlorpyrifos. J. Sep. Sci. 2020, 43, 954–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhaisare, M.L.; Gedda, G.; Khan, M.S.; Wu, H.F. Fluorimetric detection of pathogenic bacteria using magnetic carbon dots. Anal. Chim. Acta 2016, 920, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morales-Narváez, E.; Naghdi, T.; Zor, E.; Merkoçi, A. Photoluminescent lateral-flow immunoassay revealed by graphene oxide: Highly sensitive paper-based pathogen Detection. Anal. Chem. 2015, 87, 8573–8577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, Y.C.; Fang, H.Y.; Chen, D.H. Fabrication of Ag/ZnO/reduced graphene oxide nanocomposite for SERS detection and multiway killing of bacteria. J. Alloys Compd. 2017, 695, 1145–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yang, J.; Zhong, T.; Zhao, N.; Liu, Q.Q.; Shi, H.F.; Xu, H.M. Fast and green synthesis of silver nanoparticles/reduced graphene oxide composite as efficient surface-enhanced Raman scattering substrate for bacteria detection. Monatshefte Chem. 2017, 148, 1155–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, N.; Chang, B.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Z.; Wu, S. Salmonella typhimurium detection using a surface-enhanced Raman scattering-based aptasensor. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2016, 218, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, P.; Yan, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Du, Y.; Qu, C.; Song, Y.; Zhou, D.; Qu, S.; et al. Cell-based fluorescent microsphere incorporated with carbon dots as a sensitive immunosensor for the rapid detection of Escherichia coli O157 in milk. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2021, 179, 113057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Lu, C.; Li, Y.; Xue, L.; Zhao, C.; Tian, G.; Bao, Y.; Tang, L.; Lin, J.; Zheng, J. Gold nanobones enhanced ultrasensitive Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering aptasensor for detecting Escherichia coli O157:H7. ACS Sens. 2020, 5, 588–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Duan, N.; He, C.; Yu, Q.; Dai, S.; Wang, Z. Surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopic–based aptasensor for Shigella sonnei using a dual-functional metal complex-ligated gold nanoparticles dimer. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2020, 190, 110940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghani, Z.; Mohammadnejad, J.; Hosseini, M.; Bakhshi, B.; Rezayan, A.H. Whole cell FRET immunosensor based on graphene oxide and graphene dot for Campylobacter jejuni detection. Food Chem. 2020, 309, 125690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Li, Y.; Xu, Y.; Gan, Z.; Zou, X.; Shi, J.; Huang, X.; Li, Z.; Li, Y. Green one-step synthesis of carbon quantum dots from orange peel for fluorescent detection of Escherichia coli in milk. Food Chem. 2021, 339, 127775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aisyiyah Jenie, S.N.; Kusumastuti, Y.; Krismastuti, F.S.H.; Untoro, Y.M.; Dewi, R.T.; Udin, L.Z.; Artanti, N. Rapid fluorescence quenching detection of Escherichia coli using natural silica-based nanoparticles. Sensors 2021, 21, 881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Awwal, N.; Masjedi, M.; El-Dweik, M.; Anderson, S.H.; Ansari, J. Nanoparticle immuno-fluorescent probes as a method for detection of viable E. coli O157:H7. J. Microbiol. Methods 2022, 193, 106403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manoharan, H.; Kalita, P.; Gupta, S.; Sai, V.V.R. Plasmonic biosensors for bacterial endotoxin detection on biomimetic C-18 supported fiber optic probes. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2019, 129, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Wang, H.; Xu, X. Amikacin- and AuNP-mediated colorimetric biosensor for the rapid and sensitive detection of bacteria. LWT 2022, 172, 114189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdoodt, N.; Basso, C.R.; Rossi, B.F.; Pedrosa, V.A. Development of a rapid and sensitive immunosensor for the detection of bacteria. Food Chem. 2017, 221, 1792–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, F.; Yan, C.; Jia, Q.; Wu, W.; Cao, Y. A Novel Aptamer Lateral Flow Strip for the Rapid Detection of Gram-positive and Gram-negative Bacteria. J. Anal. Test. 2023, 7, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gloag, L.; Mehdipour, M.; Chen, D.; Tilley, R.D.; Justin Gooding, J.; Gloag, L.; Mehdipour, M.; Chen, D.; Tilley, R.D.; Gooding, J.J. Advances in the application of magnetic nanoparticles for sensing. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, 1904385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Zheng, L.; Cai, G.; Liu, N.; Liao, M.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Lin, J. A microfluidic biosensor for online and sensitive detection of Salmonella typhimurium using fluorescence labeling and smartphone video processing. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2019, 140, 111333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, E.; Li, D.; Yin, P.; Xie, Q.; Li, Y.; Lin, Q.; Duan, Y. A novel surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS) strategy for ultrasensitive detection of bacteria based on three-dimensional (3D) DNA walker. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2021, 172, 112758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Zhou, M.; Li, Y.; Liang, Z.; Li, Y.; Yu, L.; Liu, Y.; Liang, Y.; Chen, L.; Yang, C. A new optical fiber probe-based quantum dots immunofluorescence biosensors in the detection of Staphylococcus aureus. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Huang, R.; Li, G.; He, Y.; Chen, C.; Xiao, W.; Ding, P. Optimization of synthesis and modification of ZnSe/ZnS quantum dots for fluorescence detection of Escherichia coli. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2017, 18, 3654–3659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, L.; Zheng, L.; Zhang, H.; Jin, X.; Lin, J. An ultrasensitive fluorescent biosensor using high gradient magnetic separation and quantum dots for fast detection of foodborne pathogenic bacteria. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2018, 265, 318–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, L.; Xue, L.; Huang, F.; Cai, G.; Qi, W.; Zhang, M.; Han, Q.; Wang, Z.; Lin, J. A Microfluidic biosensor based on magnetic nanoparticle separation, quantum dots labeling and MnO2 nanoflower amplification for rapid and sensitive detection of Salmonella typhimurium. Micromachines 2020, 11, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Kumari, A.; Kaushal, N.; Saifi, A.; Mohanta, G.; Sachdev, A.; Kumar, K.; Deep, A.; Saha, A. Recent advances in the applications of carbon nanostructures on optical sensing of emerging aquatic pollutants. ChemNanoMat 2022, 8, e202200011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiremath, S.D.; Bhosle, A.A.; Nayse, A.; Biswas, S.; Biswas, M.; Bhasikuttan, A.C.; Banerjee, M.; Chatterjee, A. A redox-coupled carbon dots-MnO2 nanosheets based sensory platform for label-free and sensitive detection of E. coli. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2021, 339, 129918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A.H.A.; Bergua, J.F.; Morales-Narváez, E.; Mekoçi, A. Validity of a single antibody-based lateral flow immunoassay depending on graphene oxide for highly sensitive determination of E. coli O157:H7 in minced beef and river water. Food Chem. 2019, 297, 124965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ondera, T.J.; Hamme, A.T. A gold nanopopcorn attached single-walled carbon nanotube hybrid for rapid detection and killing of bacteria. J. Mater. Chem. B 2014, 2, 7534–7543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosbach, K. Molecular imprinting. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1994, 19, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piletsky, S.A.; Subrahmanyam, S.; Turner, A.P.F. Application of molecularly imprinted polymers in sensors for the environment and biotechnology. Sens. Rev. 2001, 21, 292–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emir Diltemiz, S.; Denizli, A.; Ersöz, A.; Say, R. Molecularly imprinted ligand-exchange recognition assay of DNA by SPR system using guanosine and guanine recognition sites of DNA. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2008, 133, 484–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayden, O.; Mann, K.J.; Krassnig, S.; Dickert, F.L. Biomimetic ABO Blood-Group Typing. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006, 45, 2626–2629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gast, M.; Sobek, H.; Mizaikoff, B. Advances in imprinting strategies for selective virus recognition a review. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2019, 114, 218–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idil, N.; Hedström, M.; Denizli, A.; Mattiasson, B. Whole cell based microcontact imprinted capacitive biosensor for the detection of Escherichia coli. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2017, 87, 807–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asliyüce, S.; Bereli, N.; Uzun, L.; Onur, M.A.; Say, R.; Denizli, A. Ion-imprinted supermacroporous cryogel, for in vitro removal of iron out of human plasma with beta thalassemia. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2010, 73, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altintas, Z.; Guerreiro, A.; Piletsky, S.A.; Tothill, I.E. NanoMIP based optical sensor for pharmaceuticals monitoring. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2015, 213, 305–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gascoine, P.; Lacey, R.; Wren, S.P.; Sun, T.; Karim, K.; Piletsky, S.A.; Grattan, K.T.V. Computational design and fabrication of optical fibre fluorescent chemical robes for the detection of cocaine. J. Light. Technol. 2015, 33, 2572–2579. [Google Scholar]

- Agasti, S.S.; Rana, S.; Park, M.H.; Kim, C.K.; You, C.C.; Rotello, V.M. Nanoparticles for detection and diagnosis. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2010, 62, 316–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idil, N.; Bakhshpour, M.; Perçin, I.; Mattiasson, B. Whole cell recognition of Staphylococcus aureus using biomimetic SPR sensors. Biosensors 2021, 11, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özgür, E.; Topçu, A.A.; Yılmaz, E.; Denizli, A. Surface plasmon resonance based biomimetic sensor for urinary tract infections. Talanta 2020, 212, 120778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gür, S.D.; Bakhshpour, M.; Denizli, A. Selective detection of Escherichia coli caused UTIs with surface imprinted plasmonic nanoscale sensor. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2019, 104, 109869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çimen, D.; Aslıyüce, S.; Tanalp, T.D.; Denizli, A. Molecularly imprinted nanofilms for endotoxin detection using an Surface Plasmon Resonance sensor. Anal. Biochem. 2021, 632, 114221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akgönüllü, S.; Armutcu, C.; Denizli, A. Molecularly imprinted polymer film based plasmonic sensors for detection of ochratoxin A in dried fig. Polym. Bull. 2022, 79, 4049–4067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akgönüllü, S.; Yavuz, H.; Denizli, A. SPR nanosensor based on molecularly imprinted polymer film with gold nanoparticles for sensitive detection of aflatoxin B1. Talanta 2020, 219, 121219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkmen, D.; Yilmaz, T.; Bakhshpour, M.; Denizli, A. An alternative approach for bacterial growth control: Pseudomonas spp. imprinted polymer-based surface plasmon resonance sensor. IEEE Sens. J. 2022, 22, 3001–3008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezdekova, J.; Zemankova, K.; Hutarova, J.; Kociova, S.; Smerkova, K.; Adam, V.; Vaculovicova, M. Magnetic molecularly imprinted polymers used for selective isolation and detection of Staphylococcus aureus. Food Chem. 2020, 321, 126673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Cui, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, J. Preparation of fluorescent molecularly imprinted polymers via pickering emulsion interfaces and the application for visual sensing analysis of Listeria Monocytogenes. Polymer 2019, 11, 984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Li, J.; Song, X.; Xu, K.; Wang, J.; Zhao, C. Label-Free Detection of Staphylococcus aureus based on bacteria-imprinted polymer and turn-on fluorescence probes. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2021, 4, 420–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Cid, P.; Jiménez-Rosado, M.; Romero, A.; Pérez-Puyana, V. Novel Trends in Hydrogel Development for Biomedical Applications: A Review. Polymer 2022, 14, 3023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Y.; Yu, M.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Long, L.; Tan, H.; Li, N.; Xu, L.; Xu, J. Highly sensitive strain sensor and self-powered triboelectric nanogenerator using a fully physical crosslinked double-network conductive hydrogel. Nano Energy 2022, 104, 107955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C.; Huang, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, Z.; Chen, C.; Ye, Y.; Guo, S. Robust superhydrophobic wearable piezoelectric nanogenerators for self-powered body motion sensors. Nano Energy 2023, 107, 108095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Wang, H.; Wang, J.; Chen, Y.; Li, C.; Zhong, K.; Xiang, J.; Jia, P. Fabrication of a High-Strength, Tough, Swelling-Resistant, Conductive Hydrogel via Ion Cross-Linking, Directional Freeze-Drying, and Rehydration. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2023, 9, 2694–2705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Agate, S.; Salem, K.S.; Lucia, L.; Pal, L. Hydrogel-Based Sensor Networks: Compositions, Properties, and Applications—A Review. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2021, 4, 140–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Zhai, J.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, N.; Xie, X. Hydrogel-Based Optical Ion Sensors: Principles and Challenges for Point-of-Care Testing and Environmental Monitoring. ACS Sens. 2021, 6, 1990–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.; Wu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, D.; Meng, L.; Chen, Y.; Tang, X. Recent applications of hydrogels in food safety sensing: Role of hydrogels. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 129, 244–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, J.; Tanner, M.G.; Venkateswaran, S.; Stone, J.M.; Zhang, Y.; Bradley, M. A hydrogel-based optical fibre fluorescent pH sensor for observing lung tumor tissue acidity. Anal. Chim. Acta 2020, 1134, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunda, N.S.K.; Chavali, R.; Mitra, S.K. A hydrogel based rapid test method for detection of Escherichia coli (E. coli) in contaminated water samples. Analyst 2016, 141, 2920–2929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.; Macconaghy, K.I.; Guarnieri, M.T.; Kaar, J.L.; Stoykovich, M.P. Quantification of Metabolic Products from Microbial Hosts in Complex Media Using Optically Diffracting Hydrogels. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2022, 5, 1252–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Li, G.; He, Y.; Luo, D.; Li, L.; Guo, J.; Ding, P.; Yang, F. High-efficient and sustainable biodegradation of microcystin-LR using Sphingopyxis sp. YF1 immobilized Fe3O4@chitosan. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2020, 185, 110633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Li, S.; Ye, X.; Ning, B.; Bai, J.; Peng, Y.; Li, L.; Han, T.; Zhou, H.; Gao, Z.; et al. Cu/Au/Pt trimetallic nanoparticles coated with DNA hydrogel as target-responsive and signal-amplification material for sensitive detection of microcystin-LR. Anal. Chim. Acta 2020, 1134, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Mao, Y.; Huang, D.; He, Z.; Yan, J.; Tian, T.; Shi, Y.; Song, Y.; Li, X.; Zhu, Z.; et al. Portable visual quantitative detection of aflatoxin B1 using a target-responsive hydrogel and a distance-readout microfluidic chip. Lab Chip 2016, 16, 3097–3104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Idil, N.; Aslıyüce, S.; Perçin, I.; Mattiasson, B. Recent Advances in Optical Sensing for the Detection of Microbial Contaminants. Micromachines 2023, 14, 1668. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi14091668

Idil N, Aslıyüce S, Perçin I, Mattiasson B. Recent Advances in Optical Sensing for the Detection of Microbial Contaminants. Micromachines. 2023; 14(9):1668. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi14091668

Chicago/Turabian StyleIdil, Neslihan, Sevgi Aslıyüce, Işık Perçin, and Bo Mattiasson. 2023. "Recent Advances in Optical Sensing for the Detection of Microbial Contaminants" Micromachines 14, no. 9: 1668. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi14091668