1. Introduction

During the last few decades Spain has experienced a staggering growth of its migrant populations, rising from 0.52% in 1981 to 14% in 2011. Today, with the collapse of the economy and the burst of the real estate bubble, unemployment has soared to 5 million people, 21% of the active population—and 43% in the case of the young population. Today, and for the first time during the last three decades, the migration rate is negative—more people are leaving than arriving. The general economic contraction in terms of economic growth, consumption, savings and public expenditure has meant the ruin of many enterprises and economic initiatives. However, in such a somehow dramatic scenario, small business run by migrants are doing quite well, particularly in the service sector.

In the region of Catalonia, the service sector generated 63.1% of its GDP in 2001, with a prominent role in trading and tourism (which account for 35% of the total value of the services sector). During the first nine months of 2011, Catalonia received over 10 million tourists, translating into a profit of 8000 million euros [

1]. Amongst the most successful spots, the touristic resort of Lloret de Mar stands out. Tourism generates over 60% of its GDP and creates most of the local jobs, turning it into the fifth beach destination in volume of hotel rooms in Spain. Today it is the first touristic destination in Catalonia in terms of hotel bookings, and tourist spending reaches 430 million euros a year.

Lloret de Mar is a seashore tourist village located on the coast of Gerona, Catalonia. Formerly, its traditional local economy was primarily based on fishing and agriculture, although in the 18th century its port had already earned commercial relevance, and these traditional activities were gradually displaced and replaced by a nascent and profitable tourism sector. Initially, the resort attracted wealthy English and German tourists. During the 1950s, local dwellers, and particularly housewives who embarked on amateur entrepreneurship, started to rent rooms to a growing number of visitors. From the 1960s onwards, tourism underwent a fast and deep developmental momentum led both by Franco’s dictatorial regime and by the British tour-operator companies such as Thomson and Clarkson [

2]. From that point on, tourism grew steadily, transforming the small fishing village into a typical mass-tourism destination. Thus, whereas in the 1950s the town had only nine hotels, today it offers more than thirty-one thousand hotel rooms, over one hundred thousand apartments, and approximately two thousand camping sites. In fact, Lloret is well known in Europe for offering low-cost, all-inclusive packages to low-income Europeans (chiefly from Germany, Britain, France and, recently, Russia) who arrive

en masse in search of fun, beach, sun, food, drinks, partying, and the local cultural stereotypes—

flamenco,

paella,

toros, and so on [

3]. Nonetheless, the place is by no means what one might consider a typical Spanish village: its population, economy, infrastructure and sociocultural realities are indeed multicultural, heterogeneous and, in fact, distant from any traditional or cultural Spanish essence. Because of its low-cost character, Lloret de Mar has suffered from the same problems that many other mass touristic places have encountered: vandalism, noise pollution, alcohol and drug abuse, and lack of control. An illustrative example of that is the so-called

balconing phenomenon, a senseless practice usually performed by young drunken European tourists which consists in jumping from the balconies of the hotel straight to the swimming pool or to simply scuttle up the sides of buildings and jump from one balcony to another, causing injuries and even death. Recently, in order to portray a better image of Lloret de Mar, the population and the local administration have attempted to promote instead both strategic quality tourism and family tourism.

During the 1970s, tourism development caused a dramatic population growth triggered by both external (Europeans who established their second residence in Lloret) and internal (workers from Andalusia, Extremadura and Galicia seeking out job opportunities) immigration. In a nutshell, in less than half a century, the population of Lloret de Mar has increased twelve-fold and today’s population comprises 40,000 inhabitants concentrated in an area of just 48.7 km

2. Due to the general process of immigration, the number of newcomers from diverse origins has increased in the past three decades. Furthermore, during the summer months, the local population usually doubles or even triples. Nowadays, the permanent population mainly comprises Spanish (57%), EU residents (17.5%), Latin-Americans (6.2%), Africans (5%), and Asians (5%) [

4].

Amongst these newcomers, the arrival of Sindhi and Punjabi Indians is especially noticeable. They have quickly settled, scattered and expanded their businesses across town. Overall, there are at least 150 businesses run by Indians, and their community includes 2000 people, mostly males coming from deprived socioeconomic backgrounds. This population represents almost 4% of the foreign dwellers living in Lloret de Mar, whereas the Indian population settled in all of Spain represents just 0.07% of the whole population [

4]. Their presence in the country should be attributed—in the absence of relevant historical, sociocultural or political bilateral contacts between both countries—to the Indian Diaspora [

5], a particular migratory pattern that consisted of the expansion of Indian communities to different parts of the world through four main flows—the pre-colonial era, the indentured workers during the British colonization, skilled workers’ migration after the partition of India and, since the end of the 20th century, a new wave of highly qualified professionals and technologists [

6,

7,

8].

The link between India, businesses and migration, however, is deeper and longer lasting. Indian entrepreneurs, who share a history of being transnational merchants and traders, have typically settled in free ports. This explains the early presence of Indians in Gibraltar, Andorra and the Canary Islands, where they settled during the second half of the 19th century and again during the 1960s and early 1970s. Drawn by the economic opportunities of tourism, pioneering Indian entrepreneurs arrived from Andorra and Barcelona (particularly after the Olympic Games of Barcelona in 1992) and spread along the northwestern coastal corridor, establishing their businesses across popular tourist spots such as Calella, Benidorm, Blanes, Salou and Lloret de Mar. They were followed by other countrymen who joined as employees and pretended to follow the steps of their bosses. Consequently, some of them eventually became entrepreneurs themselves. The new Indian entrepreneurship quickly displaced local (Catalan) and other (mostly Pakistani and Moroccans) competitors alike, and Moroccans were forced to specialize in other sectors (e.g., furriery, leather products, etc.), but most local retailers were pushed to rent or sell their stores. In the meantime, other ethnic businesses arrived and expanded, diversifying the local economy to meet new demands: Russian grocery stores, real estate agencies aimed at former Soviet Union clients; Chinese bars, supermarkets and bazaars; English pubs and German bars; Latin-American restaurants, halal butcher shops, etc.

What is remarkable in this case is the overwhelming presence of Indian workers and entrepreneurs in the service, particularly within the tourist sector: restaurants and fast-food chains (Tandoori restaurants, Turkish Döner kebabs, etc.), hairdressers, liquor stores, shoe shops and, above all, souvenir shops. A representative sample of 60 stores from the main commercial spots shows that the souvenir retail shops comprise 40% (24) of the stores, and Indians manage 92% of these, while “local” shopkeepers just run two in this area. Restaurants, bars, fast-food outlets and other food shops comprise 32% (19) of the sample: 10% of these are managed by Indians, and the rest (13) are run by local Catalans, British, Germans, Dutch or Latin-Americans. We also find two liquor stores that are both run by Indians, as it occurs in most of the cases observed in Lloret de Mar. The rest of the businesses found in the sampled area comprise generic services and tourist-orientated shops run by diverse collectives, both immigrants (Indians included) and locals: tattoo shops, “locutorios” (long-distance phone centers), traditional Moroccan jewelry, hairdressers, small supermarkets, and grocery stores.

It seems clear that in Lloret de Mar the “souvenir industry” is almost exclusively run by Indians. Throughout the exploitation of this particular economic niche, Indian businesses are coping quite well with the economic crisis since co-national workers keep arriving and joining it.

The souvenir retail sector involves at least 80% of the Indian entrepreneurs, retailers, storekeepers, traders, and workers. This sector is not a marginal one; it has hitherto been the main source of income for local entrepreneurs and shopkeepers. It is seasonal and its major activity happens during the summer, between June and the end of September. As a consequence, the Indian economy in Lloret de Mar appears to be a resilient economic “island” with a particular structure and its own external and internal socioeconomic connections. How can we explain such a concentration of businesses and Indian workers in that site? What kind of mechanisms do they share in order to resist the economic crisis? And what kind of internal socioeconomic structure do they present? Departing from these guiding inquiries our purpose is to unveil, throughout ethnographic and quantitative data, how this apparently typical tourist site hides indeed a vast, dense and complex micro-social reality with different social layers, varying interests and potential conflicts.

The unusual concentration of Indians both in an economic sector and in a given geographical area is well captured by the theoretical concept of “ethnic enclave” [

9,

10,

11], understood as a socioeconomic and cultural complex that provides economic advantages (which the mainstream economy would not be able to provide), to a certain population in a specific location. Ethnic enclaves appear more often in urban, multicultural, and dual labor market contexts [

12]. In Spain, we can add, the presence of ethnic enclaves is a sign of noteworthy sociocultural and economic complexity; especially if we take into account the fact that society was quite homogeneous until the 1980s.

The ethnic enclave theory was originally developed in the USA to explain the concentration of ethnic Cubans in Miami, although it was soon adopted to describe similar cases relating to those of Chinese and Korean origin in Los Angeles [

13], or of Pakistani roots in Manchester [

14]. Initially developed to analyze and to understand how newcomers adapted and integrated in the American society, it was built on previous theories of dual market theories [

15] and the theory of middleman minorities [

16]. According to Kaplan and Li [

17], an “ethnic enclave economy” is defined as:

… possessing a sizeable entrepreneurial class with diverse economic activities, and co-ethnicity between owners and workers and, to a lesser extent, consumers. But most importantly, they must evidence a geographic concentration of ethnic economic activities within an ethnically identifiable neighborhood with a minimum level of institutional completeness.

The ethnic enclave is a particular case of ethnic economy [

18]. Its main characteristic is the permanent concentration of a migrant population of the same ethnic group in a particular location (typically an urban area), who will eventually develop a variety of ethnic enterprises in a given specialized economic sector with a significant presence of co-national workers. But beyond its economic significance, the enclave can also be seen as a community strategy to overcome the barriers to access the mainstream labor market—labor being one of the most relevant paths to attain social integration—and to play a relevant societal role in terms of sociocultural cohesion, economic performance, and urban regeneration. According to the theory, in the ethnic enclave, ethnic solidarity articulates several forms of capital based on a common, shared ethnic identity: social capital (e.g., informal credit systems), relational capital (e.g., contacts, information, social networking,

etc.), and human capital (job opportunities, informal education, entrepreneurial training…). The enclave also reduces labor costs, increases competitiveness, and prevents undesirable consequences, because labor recruitment usually takes place through personal networks—

i.e., since workers come with references, they are loyal, flexible and adapt easily.

Yet the case of the Indian enclave in Lloret de Mar presents some particularities. First, it contradicts mainstream sociological approaches since most authors deny the existence of ethnic enclaves in Spain due to the limited duration of migrant settlements and the relatively small size of their entrepreneurial communities, especially when compared to Cuban enclaves in Miami, Chicano enclaves in Los Angeles, or Chinese settlements in New York [

10,

11,

12,

13]. Secondly, and contrarily to what is commonly found, this case lacks both a fundamental supply for an ethnic-orientated demand and an ethnic quarter: Indians are orientated towards tourists in a non-marginal economic niche.

In this way, the aim of this paper is twofold. On the one hand, it seeks to provide a detailed description, using a mixed-method approach, of the emergence and expansion of an Indian economic enclave in a highly competitive tourist resort in Spain. The description will stress the resilient character of the enclave in a context of economic crisis and hardship, and it will provide a better understanding of the internal structure of the enclave in terms of socioeconomic arrangements and ethnic/class inequalities, too. On the other hand, it aims to be more theoretical in scope: it confirms the mixed embeddeness hypothesis to a certain extent, and it develops a discussion on how migrants establish and expand their social ties within the “host society”.

For this purpose, the article will develop the following sections; firstly methodology and techniques; then a discussion on the composition and nature of the ethnic enclave, its internal structure and the characteristics of the social networks of their members; and an approach to the local potential conflict. Finally, some conclusions are presented.

3. Discussion

In this section we will firstly describe the distinctive qualities of the enclave regarding the economic niche and its main commodity, the souvenir. Secondly, we will describe the structural composition and the social dynamics of the enclave. And thirdly, we will expose social inequalities within the enclave and between the Indian community and the wider society [

23].

3.1. The Souvenir Retail Sector and the Enclave

The souvenir retail sector shares some distinctive qualities that partly explain the development of an ethnic enclave and the attraction of non-skilled migrant workers and Indian businessmen: a) it is a seasonal activity, encompassing eight to nine months of work per year, with a peak during the summer; b) no particular human capital is needed to work in the sector: the souvenir is a very unspecific good (it might range from T-shirts, to postcards, beach towels, and even Mexican hats!), and no special skills, technical knowledge or even language proficiency is needed (some keywords in Spanish, English, Italian, German, French and Russian are enough); c) running the business does not require great economic capital, either. Although rent is expensive (from €30,000 to €60,000 annually, depending on the location), monthly payment and the provision of stock in advance by truthful dealers make the starting point relatively easy. Since an available workforce is abundant and inexpensive—due to a large pool of Indian workers willing to work under pressing conditions—overall profits are relatively good; d) innovation is rare and hardly successful because the kind of tourist that visits Lloret de Mar (students, youngsters, low-income tourists) are neither very selective nor sophisticated: they either look for standardized, cheap, stereotyped souvenirs somehow related to a stereotyped Spanish culture, or they are solely interested in the partying character of the resort; e) on the other hand, the sector is highly adaptable to small changes in, or alteration of, demand. In the cases in which one new product becomes successful (for instance, a particular T-shirt, umbrella, or a toy bagatelle made in China), it is rapidly plagiarized. According to one Indian shopkeeper: “these kind of commodities is what they are looking for (…) we do not make it difficult because another good is not going to work: this is a seasonal good and this is what these tourists want”; f) marketed goods are almost identical—because they are all provided by the same dealers—and, therefore, competition is extremely tough internally and externally (amongst Indians and between Indians and the rest).

The competitive pricing (accompanied by credit provided by the wholesalers), the externalization of personnel costs (due to unpaid family work and the employees’ circular migration), and the effective management of owners who are well connected to the local community through personal contacts carved out during long periods of residency, make these businesses very competitive and explain the replacement of former local and Moroccan dealers. One key aspect of the Indian success lies in performing what the anthropologist Clifford Geertz (1978) called

bazaar economy [

24], an imported commercial model from the countries of origin consisting in applying the maxims of the formal economy: everyone wants to buy cheap and sell expensive, the price is related to supply and demand, and there is free competition. The bazaar economy encompasses practices like bargaining, working long shifts, locating part of the stock out of the store, or attempting to convince customers to purchase their products.

3.2. Structural Composition of the Ethnic Enclave

Within the ethnic enclave there are different categories of employers and employees. Amongst the former we find entrepreneurs who own one or several businesses, and Indian shopkeepers who are not proprietors but rent the premises of third parties (usually local landlords). The latter usually operate at a smaller business scale due to these hiring constrictions and lack of capital. The average rental price for a shop in the town fluctuates from €40,000 to €60,000 annually, and shopkeepers are pressed to sell a certain amount of goods in order to obtain a minimum profit. Multi-owners tend to delegate the management of their stores to their relatives (children, wives, brothers) who, in turn, supervise one or two Indian workers per shop.

Almost all successful Indian proprietors have been living in Spain for a long time (usually over fifteen years), and they have already acquired Spanish nationality. Their level of expertise is quite high within their own business sector, as most started working in the sector as employees themselves. During those years, they accrued enough capital to further expand in the same or other economic sectors, and they built an extensive social network that includes both local Spaniards of different professional statuses and an ample cluster of locally residing countrymen. Having several stores involves the possibility of dealing with larger capitals and bulkier volumes of goods, placing these owners in a more advantageous position than other entrepreneurs vis-à-vis the suppliers. The high level of local embeddedness and prestige within their own community makes them crucial middlemen between both communities. In fact, these entrepreneurs play a relevant local role promoting and fostering Hindu culture and traditions, even though their contact with the homeland is already sparse and discontinuous.

Most, if not all, Indian businessmen consider education a central tenet for upward socioeconomic mobility and they are in many cases proud parents of motivated children who perform well at formal education (usually in technical or scientific careers). Members of this small and select group of businessmen (with no more than 10 members) are cohesive and well attuned: they offer mutual support when needed in the form of financial and business information, manpower provision or informal loans with slight or no interest [

25].

Both renters and owners (mostly Sindhis) exclusively employ co-national Indian workers (mostly Punjabi), adducing that “it is simpler to work with them and easier to understand each other”. This may be true, but the fact is that co-nationals represent a wide pool of men who are less reluctant than other local or other emigrant workers to accept less advantageous labor conditions in terms of contract, salary or working schedule.

Employees are in most cases young and middle-aged men from depleted rural and urban Indian backgrounds. Businesses and migration are in this case usually a masculine matter. Men account for 70% of the population and, as it happens with other communities in Spain (of Pakistani or Bangladeshi origin, for instance), their public presence and their role in the businesses is still very limited. The chain of migration is normally driven by family or by the former acquaintances and, once in Lloret de Mar, the employees are hired by owners of other ethnic origin. They have usually been in Spain for less than five years and their degree of local integration is poor in terms of socioeconomic, cultural or linguistic interaction with locals. When interviewed, most of these workers affirm that their aim is to be self-employed in the long run. Self-employment is a major motivation for this community in particular. As a Moroccan shopkeeper describes it: “Most of them leave their country to succeed, to work, and they have a strong desire to improve (...) they do not care to work long hours for low salaries.” Some of them decided to work in the industrial or agricultural sector as a way to save money and establish their own business faster. In some of the cases, we observe that when an employee has been working long enough for the same person, he will eventually get help from his boss to create his own business. However, economic competition is fierce within the ethnic market and not all employers are willing to do so.

Still, among workers or employees, there are some internal inequalities related to ethnic origin that might affect recruitment preferences and strategies, internal alliances (in terms of religious or regional affinities) or rivalries—although we contend that more research is needed in this line in order to confirm such assertions. As one Sikh male put it:

Now there are more Sikhs than Lloret Hindus. All the workers here are Sikhs. In many stores the owners are Hindus, but the workers are Sikhs. There are some Sikhs who are also owners, they have restaurants. But we have not been here for a long time…Hindu–Sikh, there are no problems; we all have respect, the same language.

(13H01G)

Employees’ expenditure habits are austere for several reasons: the demanding working hours leave them little margin for leisure, they usually share home and living expenses with other countrymen, and their vital and social interests remain in India, where they anxiously expect to return to when possible. Indian workers in general are involved in a kind of

circular migration [

26] between their homeland and Lloret de Mar. According to 13H01G (Sikh employee), “Stores close for three months, usually from the 15th November to 15th February. During this period I go back to India and I help my family with farming.” Another employee (13H05G) states: “We stay in India for two to four months, with the family, and we do not work. We usually close from January to February. In India we are with the family. We don’t work there, we enjoy life. If we earn money we spend it all.”

Such a singular pattern of migration is possible thanks to the extraordinary regularization processes conducted in Spain over the last decade. In general, there are three ways for migrants to obtain both work and residence permits in Spain: through the general scheme, via the annual quota system or through a process of extraordinary regularization. The Migration Act of 2000 states that immigrants wishing to work in Spain need a work permit before leaving their countries. In practice, the issuance of a work visa in India by a businessman based in Spain is unrealistic: the process is too complex and this modality only seems feasible when a given businessman wishes firmly to extend a contract to relatives or close countrymen. On the other hand, Indian entrepreneurs are reluctant to offer jobs to non-regularized co-nationals, because they are always at risk of workplace inspections, and penalties for irregular contracts can involve a large fine. In practice, although a minority could enter Spain with a tourist or student visa, or with both a valid or false work permit, most immigrants entered the country “illegally” and regularized their situation once in Spain. Since 1986, Spain has conducted at least six extraordinary regularization processes that have helped a vast number of immigrants become integrated in the national labor market. Between 2002 and 2005, more than 400,000 people regularized their situation and only in 2005 the Ministry of Labor and Social Security opened a special regularization period that received more than 700,000 applications, of which 90% were granted. In turn, another 400,000 people, most of whom were spouses and children under sixteen years old, obtained their “papers” by virtue of their kinship ties with the latter.

3.3. Ethnic Enclaves as Homogeneous Entities

Ethnic enclaves are usually defined as homogeneous entities without relevant internal diversity, probably because it is assumed that their members share a common goal: to integrate or assimilate within the wider society or to find a reasonable alternative to the lack of opportunities when the path to the mainstream labor market is blocked. The fact is, as we have suggested above, that we actually found a wide amalgam of relevant differences within the enclave in terms of resources, upward mobility paths, property, ethnic origin, socioeconomic background, etc.

Some authors assume that working in an enclave means obtaining advantages in comparison to the mainstream labor market: it provides better returns, equal or better returns on human capital investment, it enables access to work without having to rely on employers, it benefits the ethnic group because it increases their income levels or ensures upward mobility at least for second generations [

15,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34]. Some other authors argue precisely the opposite [

35,

36,

37,

38,

39], and point out the social costs that ethnic economies and ethnic enclaves in general represent for migrants, preventing them from being incorporated into the wider society. Some of these authors remark that advantages of the enclave are clearer to employers than to employees, as we sustain in this text. The ethnic enclave, under this negative perspective, is seen as a ghetto, an economic and cultural circumscribed reality that impedes social integration or/and assimilation of newcomers, limiting at the same time their possibilities to improve labor conditions, language proficiency, access to education, social networking and capital, or even the possibilities to marry outside of the ethnic group. All these factors are indeed clear barriers to such integration or assimilation within the wider society. According to these authors, too, the non-wage rewards adduced seem restricted to co-ethnic workers recruited through personal networks and, therefore, workers are usually loyal, flexible and less reluctant to accept lower wages.

In fact, these contradictory views can be overcome by paying more attention to the internal differences and inequalities within the ethnic enclaves, a reality that has been scarcely analyzed or addressed from the ethnic economy theory. More specifically, the analysis of the personal networks [

40] shows that employers’ networks are more geographically dispersed, with social relationships located both in origin and in destination, while employees’ networks tend to be strongly based in origin. These differences between owners and employees can be taken as a proxy of the different ways of adaptation to the host society, namely

mixed embeddedness in the first case and

circular mobility in the second one.

As the Figures show, the social networks of entrepreneurs and workers are diametrically opposed: while the former show a great degree of heterogeneity (

mixed embeddeness), with both Indian and Spanish contacts, the latter are more homogeneous, showing a majority presence of co-ethnics (of similar social background). Although visually there is a clear difference between networks, some qualitative data is needed to further explain the differences in terms of access to resources (in terms of social and economic capital) and the reasons for such differential access (see [

41]). As it will be explained, the contrasting network structures between workers and employers reflect major differences in terms of expectations, social needs, economic strategies, social mobility and integration. Using qualitative data and network analysis, we will try to show why ethnicity might sometimes be less important than class in the articulation, forging and expansion of these social ties.

According to Putnam, [

42] ties might be assessed in terms of

bonding (close ties with “people like us”) and

bridging (links beyond “group cleavages”). People may bond along some social dimensions (e.g., ethnicity) and bridge across others (e.g., class). In our case, we observed high levels of bonding along ethnicity,

i.e., relationships are formed among Indians, and between workers and employers; but less between the Indians and the Spanish. We might assert that relationships between the local Spanish population and Indians are scarce in terms of social interactions. However, Indian entrepreneurs tend to bridge ethnic divisions more easily, creating relationships with Spanish professionals from the same or other social classes. In other words, although ethnicity (bonding) hinders the relationship between locals and foreigners, we might also appreciate clear class relationships (bridging) between entrepreneurs and specific local professionals—

i.e., bridging the ethnic divide through inter-ethnic class connections.

Figure 1.

On the right, we do have a typical worker’s social network with virtually all his social relations from India and a significant part settled in this country. On the left, we have the typical social network of an entrepreneur, with virtually all contacts settled in Spain and a remarkable number of network members from Spain—generally professionals related to businesses [

43].

Figure 1.

On the right, we do have a typical worker’s social network with virtually all his social relations from India and a significant part settled in this country. On the left, we have the typical social network of an entrepreneur, with virtually all contacts settled in Spain and a remarkable number of network members from Spain—generally professionals related to businesses [

43].

Although more data is needed, we have also observed intra-ethnic differences between workers and entrepreneurs. According to our ethnographic data, Hindu-Sindhi entrepreneurs arrived first, established their business and expanded their economic influence by means of kinship links— i.e., incorporating sons, nephews or other male relatives into their businesses—and employing other co-nationals (both Punjabis and Sindhis) alike. Thereafter, and especially from 2000 onwards, Sikh Punjabis began to arrive in greater numbers. According to one worker: “there are some Punjabi that run shops, maybe seven, eight or ten, but no more. Most [of the entrepreneurs] are Sindhi, particularly here in Spain.” However, although this connection might be relevant in terms of more complex bonding/bridging relationships, it is risky to draw such strong connection based on the available data.

The observed homogeneity of personal networks, in the case of workers, reflects a lack of alternatives in terms of social integration within the local society. Circular migration, poor language command, long working hours, limited consumption, limited cultural capital and sharing most of the time and space with co-ethnics do not leave them many opportunities to interact with the local population, making it very difficult to develop weak ties with the Spanish. Furthermore, enclave completeness provides a mini Indian town in which to fulfill their immediate needs. In addition, workers generally state that they do not feel the need to meet Spanish people because their sociocultural interests and references remain in India.

Social links, however, need to be observed from both sides: Indian migrants are commonly regarded by the Spanish local population as unskilled, non-educated, or rural populations coming from low-class backgrounds—although this is not always so! In the case of Spain, conflict, inequality and resentment against migrants have been increasing during the last years for two main reasons. Firstly, because the migration rate has increased dramatically during the last three decades (see above). A relatively homogeneous local society in terms of ethnic and cultural background has experienced a fast process of ethnic diversification, and the perception and response from particular sectors of society has been one of fear, suspicion or rejection against certain communities, ethnicities or religious and cultural practices. Secondly, because foreigners have been an easy target to blame in times of unemployment and economic difficulties.

The case of Indian entrepreneurs provides a different picture. Their heterogeneous networks show high levels of bonding (with the co-ethnic cluster) and bridging (with Spanish professionals). Their role within their own community is central and influent: they do accrue significant economic and social capital and play a central role as community brokers in several spheres—from religion and culture (local Hindu association) to formal institutions (police, banks, city council, etc.).

Although most Indian entrepreneurs have previously been workers, they have experienced social upward mobility through all these years and the chance to make and extend ties with Spaniards. There is therefore an economic component in the nature of these ties that precludes open ethnic discrimination. Their extension of ties is, in general, a matter of class, but also a matter of time and space. But where are these weak ties coming from?

A great number of ties correspond to local professionals somehow related to their business: council administrative staff, lawyers, consultants, bankers and, above all, Spanish providers who, over time, have become friends. Furthermore, although it might sound trivial, proximity and time of residence do play a fundamental role in the extension of ties. According to McPherson

et al. “the most basic source of homophily is space: We are more likely to have contact with those who are closer to us in geographic location than those who are distant” (quoted in [

44] (p. 514)). On the other hand, time is also crucial: many Indian entrepreneurs have been living in town for at least fifteen years and they already have Spanish nationality. They have settled permanently in Spain with their own families and they have been forging and expanding their social contacts in a wide myriad of contexts: neighborhood, school, local shops (bakery, pharmacy, butchers, stationery shops,

etc.), local institutions (associations, city council,

etc.), local gym, and so on. As a matter of fact, when all tourists return at the end of the summer season, Lloret de Mar is a small village where everyone knows everyone else.

3.4. Opening Pandora’s Box: Inequality and Conflict

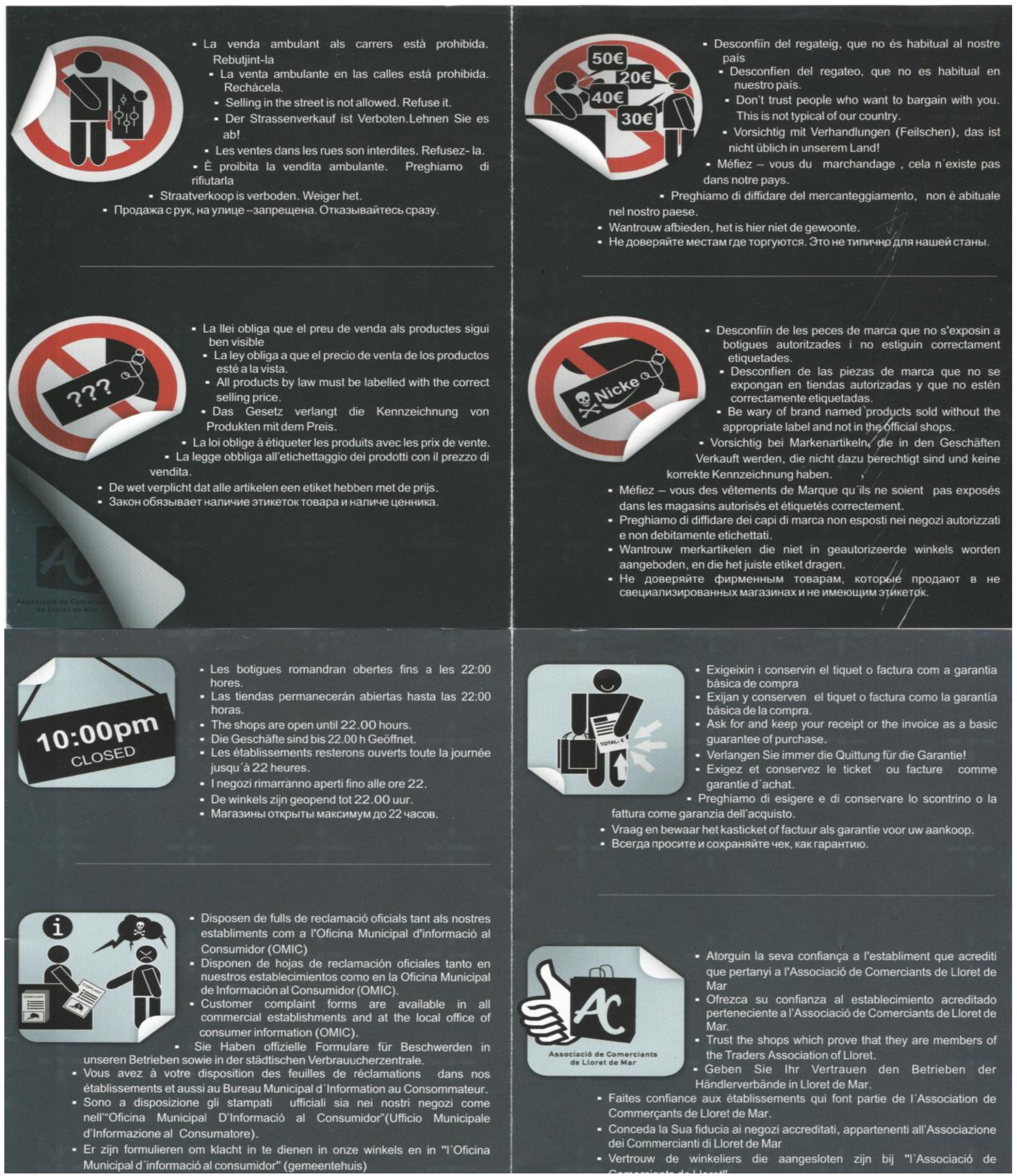

Generally, it is argued, enclave economies emerge and develop in marginal economic niches. In this case, however, the enclave economy enters in open competition with an economic sector traditionally developed and controlled by corporative local shopkeepers. Some Indian owners have tried to play an active role in the Associació de Comerciants (Local Retailers Association) but they have been unsuccessful, because Indians are seen by the local shopkeepers who still run their own shops as aggressive competitors. Such a competition has activated two types of protectionist measures: institutional and civil. In the first instance, the local council, under great pressure by native traders, has imposed stricter regulations regarding working hours (opening and closing hours), stock display (prohibition of displaying the stock outside the shop), goods (prohibition of certain products: pointer lasers, megaphones, etc.), market policy and price transparency (products must display their prices clearly). However, fighting fire with fire brings undesirable consequences for everyone. Both the Local Retailers Association and the city council have led a smear campaign against such practices, adding unproven accusations and fuelling defamation, gossip and conflict against what is seen as unfair competition and commercial practices (i.e., bazaar economy’s practices). According to one of these local retailers, “Indians come because this is a joke. They do not pay taxes, they steal…and the government does nothing.” The campaign is indeed reproducing and reinforcing negative cultural stereotypes and fostering increasing rivalries and tensions. As the picture of the flyer shows, the local campaign, translated into eight languages, is designed to tackle some misguided economic behaviors directly associated with the Indian community.

In the second instance, at the civil level, a significant portion of the local population shows open discursive hostility against Indians. Xenophobia has never been an issue in Lloret de Mar and, as we have argued above, Indians entrepreneurs do have a wide number of Spanish people in their social networks, but the economic crisis and this kind of campaigns are contributing to change the attitude of some local collectives: local shopkeepers who are still in business and social sectors particularly hit by the crisis—

i.e., unemployed and poor dwellers, for instance. As in those small rural communities typically studied by anthropologists, rumors and gossip have a persuasive effect regardless of whether they are true or false, creating and spreading stereotypes and prejudices [

45,

46,

47]. For instance, most local shopkeepers and residents of Lloret alike agreed on the following arguments based on rumors of unlikely veracity: Indian businesses enjoy moratoriums for which they are freed from when paying taxes during the first years of activity; trade is usually transferred to a family member who benefit from these exemptions; some laws openly benefit foreigners; they do not pay social insurance for the workers; most workers are illegal; these workers must work three years for free in order to repay the cost of the migration process to the employer; they sell stolen, fake or illegal goods; the ethnic enclave institution operates as a mafia when black money is laundered; they hide good prices and cheat customers; they always incur in unfair competition; they evade inspections and police control, claiming they do not understand Spanish,

etc.In this scenario, however, a flagrant contradiction arises. A great number of shops run by Indians have been previously transferred from local shopkeepers for a substantial amount of money. While on the one hand shopkeepers blame Indians for unfair competition and

cannibalistic expansion, on the other hand, economic profit prevails at the end of the day. In other words, these apparent sociocultural and ethnic conflicts seem to have economic roots. According to one local shopkeeper:

We have two more stores leased to Indians. We need to survive, we cannot…well, yes, it is a contradiction, but what can I do? And that’s what happens in Lloret…I am against what is happening, but if an Indian guy appears and offers me €60,000 straightaway, for a five-year contract, and pays for two years in advance, and I don’t even think about it...I take the money and I close down the business...

These contradictions reflect multifaceted practices and discourses in terms of class, ethnicity and economic relationships. As Ryan puts it, the distinction between bridging and bonding “tends to be understood on the basis of the ethnicity of the people involved. Therefore, insufficient attention has been paid to the actual resources flowing between these ties or to the kinds of relationships developing between the actors involved” [

41]. In this way, our case invites further applying Ryan’s suggestion. As a matter of fact, empirical studies of the agglomeration phenomenon in economic niches have shown that the nature of these dense spaces fosters competition as well as cooperation [

48]; and such competition/cooperation relationship is clearly reveled through ethnographic data.

According to Hari, a 27-year-old Indian worker: “The boss [an Indian entrepreneur] is a false bastard. He lets the system work. But, why is the city council allowing so many licenses [for Indian shops]? Sure! Because that makes money…there is no friendship here, everyone looks only their own interests. I hate the Indian economic system and the passivity of the Hindu leaders. You know? Many workers are warned not to talk to Spaniards who ask questions.”

Likewise, the relationship between owners and employees is not horizontal or equal. According to one owner, “I don’t allow any employee to visit my home. It is no good they know what I have or how I live. They only have to worry about doing a good job!” Although some employers have helped employees out to establish their own business (offering loans, contacts, advice, etc.), in general, employers are reluctant to help out workers who will probably become competitors in the future.

Indian workers and entrepreneurs, in turn, also criticize local commercial practices. As one Indian interviewee put it, “Spanish shopkeepers don’t want to work. They prefer to enjoy, to live comfortably, without striving, and to close early in the afternoon.”

The most critical and intolerant Spanish shopkeepers towards their Indian competitors were precisely those who were still in charge of their businesses. Most local shopkeepers had already rented, transferred or sold their shops to Indian shopkeepers and aversion was seldom openly displayed because it would attempt against economic interests. Furthermore, the lobby of local shopkeeper is not unitary, because some members of the Local Retailers Association do actually rent their shops to Indians.

The city official who led the campaign against the informal economy (see

Figure 2) openly stated its concern over the growing Indian presence in Lloret de Mar although, as in the case of mass tourism, the council and the local community highly benefit from that source of income. As Hari put it, a large part of the taxes collected by the municipality comes from Indian businesses: issuing permits, and fees and tax payments.

Figure 2.

Flyer of the aggressive campaign against unfair competition addressed to the clientele (tourists) in eight languages. The flyers warn about the existence of unlawful activities: informal economy, street hawking, selling of fake goods, etc., and provides some advices to fight these activities.

Figure 2.

Flyer of the aggressive campaign against unfair competition addressed to the clientele (tourists) in eight languages. The flyers warn about the existence of unlawful activities: informal economy, street hawking, selling of fake goods, etc., and provides some advices to fight these activities.

4. Conclusions

This paper has documented ethnographically the emergence and expansion of what is theoretically defined as an ethnic enclave, a protected environment operating under a niche market within an economic sector dominated by one particular ethnic group, the Indian community in this case. Through the mixed-methods approach we have attempted to show some of the obstacles migrants face in building social ties with the local host society.

The existence of ethnic enclaves in Spain is a sign of growing ethnic and sociocultural complexity. The ethnic enclave, by definition, offers sociocultural and economic protection when the access to the labor market is blocked. Furthermore, the ethnic enclave is also characterized by

institutional completeness [

49] in the sense that their ethnic population reproduces cultural, religious or social referents to fulfill their immediate needs. Nevertheless, the very nature of the enclave is contradictory. On the one hand, as we have seen, it provides a number of advantages: it strengthens cohesion and ethnic identity; it streamlines the flow of information, job opportunities and contacts; it is a learning space; it reduces labor costs,

etc. On the other hand, to be part of the enclave also means limited integration; increased domestic competition; generation of ethnic inscrutability; generation of exploitative relations,

etc. Consequently, although participation in the enclave is a potential route to overcome marginalization in the general labor market, the reality of the enclave appears to be far more complex than the theory and the classical case studies show. It could be argued that the context in which the enclave was created and developed shows complex layers where different agents target different interests or resources. In such a dense ethnographic context we find, at least, tourists; traditional local merchants; diverse kinds of ethnic entrepreneurs (from small shopkeepers to multi-owners, tenants or distributors of Indian and other origins); dealers and distributors who play a significant role in the economic niche at issue; and local dwellers and administrators who are active agents in the process of integration of the minority groups. The influence of the economic crisis, the increasing competition for limited resources and the process of expansion of the ethnic enclave, are fueling a growing social tension among these different agents.

Most authors tend to represent the ethnic enclave as a homogeneous socioeconomic entity. However, as network analysis and ethnography show, a deeply stratified relationship between employers and employees has been observed (in terms of internal ethnicity and class), thus indicating an uneven distributive flow of resources amongst the different actors. These differ in terms of social integration, time of residence, social mobility, social and economic capital and migratory patterns. While workers are involved in a pattern of circular migration that prevents their full integration in the “host society”, employers, contrary to what might seem, present low levels of transnationalism: their interests (economic, social networking, family obligations) are already in Spain (for a discussion on entrepreneurship and transnationalism, see: [

50,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56]).

To conclude, some final points might be worth considering. Most descriptions of ethnic enclaves tend to present them as cohesive homogeneous entities, therefore making it difficult to understand the internal socioeconomic dynamic, the processes of exploitation, and the resilient nature of the enclave. Our case study offers an alternate portrayal. Firstly, within the enclave, some people show high levels of transnationalism, while others display patterns of local embeddedness. More specifically, while entrepreneurs are well integrated in the host society and their visits to India are rare, employees’ level of integration is low and their contact with India is frequent by virtue of circular migration. Secondly, while most of the characteristics of the ethnic enclave exposed by the literature can be found among entrepreneurs (integration, informal credits, upward mobility, social capital, flux of ideas, etc.), most of the negative aspects of the enclave might be found instead among workers (exploitation, limited integration and upward mobility, absence of informal credit, etc.).

As the visual material demonstrated, the networks’ compositions clearly represent the contradictions and inequalities between Indian workers and entrepreneurs, which operate along with both class (employers and employees) and intra-ethnic (we assume between Punjabis and Sindhis) dynamics. Nonetheless, class relationships (particularly in the higher levels of the social strata) seem to be a relevant way of bridging. Thirdly, and in light of the need to apply further longitudinal analysis, there has been a positive correlation between time of residence and level of economic success, which therefore presumes a higher level of social integration of some Indian employees in the long run if they follow their bosses’ path. However, we prefer to be cautious in this claim, since the economic crisis is changing tendencies and the growing potential of the ethnic enclave is becoming limited.

We hope our study has served not only to illustrate ethnographically the emergence of the Indian enclave and the socioeconomic density of this tourist site; but also to contribute to the theoretical debate about the difficulties that the ethnic minority groups find when building and expanding social relationships in the “host society” during the economic crisis. Only further analysis will allow a better understanding of the synergies between minority ethnic populations and the larger ones, as well as the difficulties accompanying social integration and upward mobility.