1. Introduction

“People know what they do; frequently they know why they do what they do; but what they don’t know is what ‘what they do’ does.”

Critical discourse analysis (CDA) is a common way of analysing language use, relationships or discourses. This kind of critical analysis generally implies an analysis of text, speech, communication and conversation (

Fairclough 1995,

2003), while Foucauldian discourse analysis pays particular attention to behaviours, practices, performances and actions, and how these are regulated by power. People actively construct social norms, rules and boundaries through communicative language. Similarly, behaviour, practices and body language, as well as people’s observations and reflections (e.g., knowledge) around the actions of a collective group also create and reproduce social discourses (

Foucault 1981,

1982,

2002).

When we view power as a chain or network of social relations that can shift, or be resisted, “place” and “space” become factors that can trigger or facilitate such discursive transformations. Here, we understand “space” as a shorter-term social area that is given meaning or value in relation to a specific time, while “place” is understood as a longer-term cultural area where people feel or are aware of its sociocultural codes, attitudes and regulations. Place and space are key concepts in understanding the human impacts of mobility. A person’s physical movement from one place or space to another may shift or transform power relations (

Foucault 1977,

1982). For example, in an urban (im)mobility study carried out in an informal settlement of Bangladesh’s capital Dhaka, such shifts in gendered power relations were observed with people’s moves from rural to urban environments (

Ayeb-Karlsson et al. 2020, pp. 10–11). People migrating from rural to urban areas may in this way end up facing new socio-normative challenges as well as opportunities. The existing discursive power relations in one rural place may not apply to another rural migration destination, or an urban arrival area. The active social norms and power relations in people’s home villages are sometimes even knocked out of order, although people move together as a group (

Ayeb-Karlsson et al. 2020). Transformations of this kind can take place when people migrate together as a social group and arrive in a new environment or are introduced to new social settings.

This article elaborates the practical ways to better incorporate a discursive framework founded within social sciences and critical theory into the area of climate-induced (im)mobility. The replicable conceptual approach based on Foucauldian inspired theoretical elements (such as discourse, power, knowledge and subjectivity) presented in this article can be applied both to the study of language through textual and spoken discourse analysis, and to practices through, for example, empirical field observations or interviews that capture discursive behaviours.

It should be noted that several Foucauldian-inspired critical frameworks on top-down adaptation policy-oriented approaches to decision-making and intimate government livelihood decision-making exist (including, but not limited to,

Carr 2013,

2019;

Eriksen et al. 2015;

Manuel-Navarrete and Pelling 2015). The conceptual idea presented in this article, however, proposes a more people-centred and bottom-up approach that can capture the nuances of people’s (individuals and groups) (im)mobility decisions as well as how these relate to their wellbeing. Here, wellbeing is understood as a subjective and dynamic state of feeling healthy and happy that ties into life satisfaction and influences a person’s (or a collective’s) psychological and social function (

Diener 1984;

Ryff 1989;

Robitschek and Keyes 2009;

Joshanloo 2018).

2. Discourses: Positioning the Subject within Power and Knowledge Relations

Discourses can compete, contradict or complement one another (

Foucault 1981;

Fairclough 2003;

Ayeb-Karlsson et al. 2018). In other words, it is their structural similarities that group them together rather than their viewpoints or realities. In this conceptual context, everything is socially constructed through its discursive creation and reproduction within a collective or social group. In line with a Foucauldian understanding of this structure, it is the discursive relationship between discourse, knowledge and power that maintains everything within a functional state. People are in this way locked into discourses, through their power and knowledge relations, by responding to their emotions and feelings (

Eriksen et al. 2015;

Owusu-Daaku and Rosko 2019;

Ayeb-Karlsson et al. 2020). There can be no power without the correlative constitution of knowledge, nor knowledge that does not produce or structure power; or, as Foucault himself argues:

“All knowledge, once applied in the real world, has effects, and in that sense at least, ‘becomes true’. Knowledge, once used to regulate the conduct of others, entails constraint, regulation and the disciplining of practice. Thus, there is no power relation without the correlative constitution of a field of knowledge, nor any knowledge that does not presuppose and constitute at the same time, power relations”.

To summarise, knowledge is produced through power that produces new knowledge, that confirms social norms through people’s observations of power relations. The effects of power can in this way be a creative force or imply positive growth. From this point of view, power relations go beyond “the powerful powering the powerless”. Power is not something a social group or institution permanently possesses, but rather something that operates a consistent basis within all social relations, including in between people, or between people and institutions (

Foucault 1977,

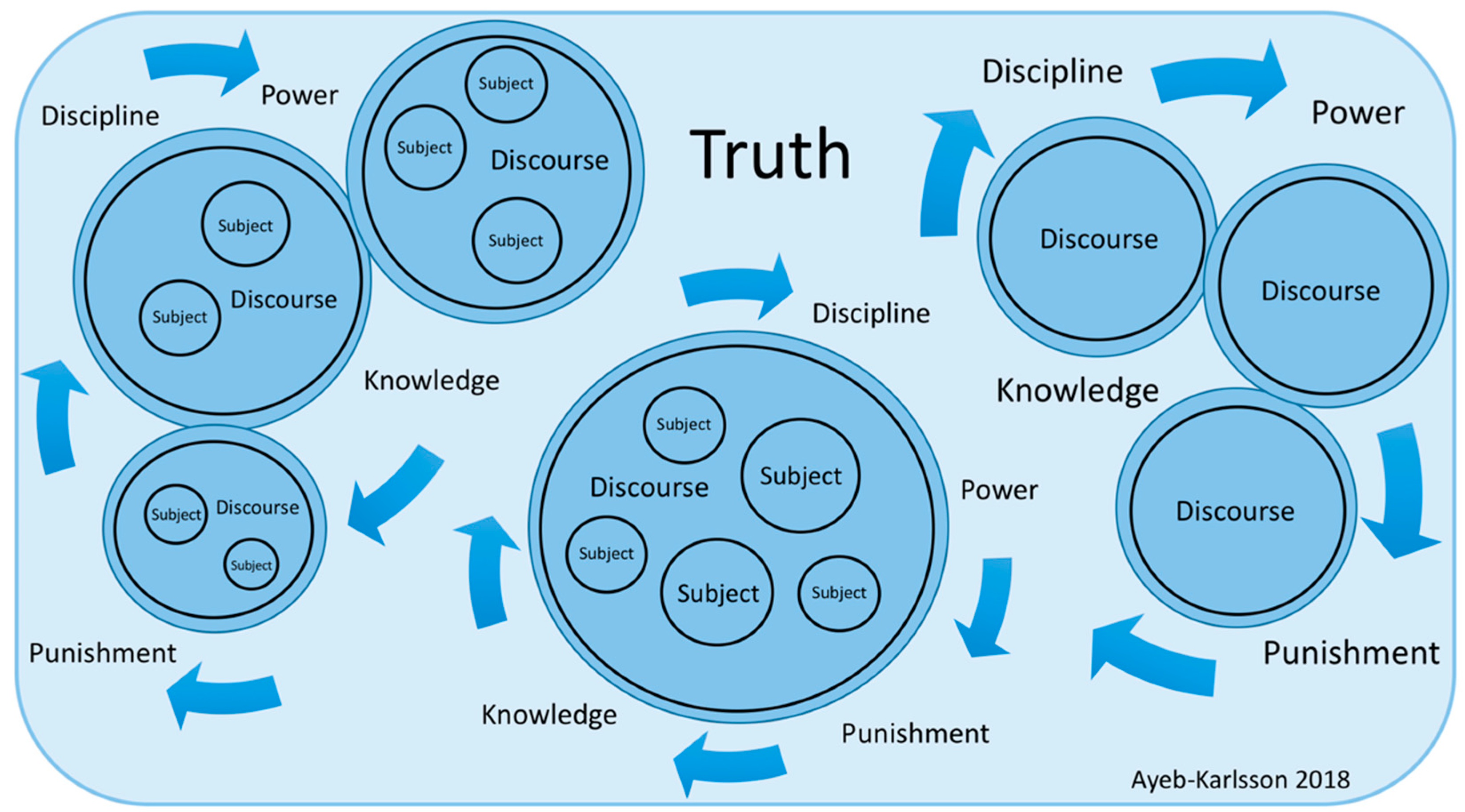

1982). Power and knowledge in this way help maintain and reproduce people (or subjects) within discourses (see

Figure 1)—“power” by socially punishing those who step outside of the social norm, and “knowledge” by disciplining people’s actions and behaviours according to what they know (

Foucault 1977,

1982;

Butler 2006;

Ayeb-Karlsson et al. 2019,

2020).

Figure 1 illustrates the subject’s (subjective) position within the collective discourses or a socially discursive reality. It also outlines how discourses can exist in one and the same world (or truth), and yet compete, contradict or complement one another. The discourse group to the left, for example, can be thought of as a complementing discourse group, while the discourse group to the right may compete against this group. In this way, discourses can exist next to one another but still have contradicting discursive viewpoints, attitudes and realities The arrows indicate the reproduction of these discursive attitudes and the productive relationship between discourses, power and knowledge that supports their survival (

Ayeb-Karlsson 2018, p. 17).

The reproduction of a specific reality, and the subject’s understanding of how it is positioned within its social context (e.g., subjectivity) is regulated by the repetition of the active knowledge and power relations. Elements of discipline, such as normative and subjective control of behaviour, thoughts and language, as well as social punishment, such as the shame and social stigma of those transgressing normative boundaries, will maintain its structure and keep the discursive reality intact.

3. Subjectivities: The Subject’s Existence in a Social Time, Place and Context

The subject–discourse relationship introduces us to our next key concept, subjectivity or self-formation. Several scholars have elaborated the conceptual understanding of subjectivities. For example, Morales and Harris define subjectivity as “how one understands oneself within a social context—one’s sense of what it means and feels like to exist within a specific place, time, or set of relationships” (

Morales and Harris 2014, p. 706), while Eriksen et al. point out how subjectivities emerge through power relations or is a “process of internalising dominant cultural codes, discourses and disciplining practices, and the acceptance of and resistance of these, processes which are always present even if often unconscious” (

Eriksen et al. 2015, p. 525). In this way, subjectivities are not understood as stable categories, but rather as dynamic exercises of power that can have contradictory and unpredictable outcomes. Adding to this, Manuel-Navarrete and Pelling similarly define subjectivities as the “dynamic positionalities that individuals take to situate themselves in relation to processes of subjectivation” (

Manuel-Navarrete and Pelling 2015, p. 561). A person’s subjectivity is in this way one amongst many coexisting possibilities of organising self-consciousness.

A Foucauldian-inspired understanding of the subject (and its freedom to choose positionalities or subjectivities) within discourses can be perceived as passive from a structuralist point of view (

Foucault 1981,

1982;

Butler 1997;

Skinner 2013). The subject appears to be locked into a discursive system or trapped within its reproductive structures. However, as the subject constantly participates in the construction of the self, and its discursive reality, it is an active “agent of change” rather than a passive respondent. Subjectivity can in this way be understood as the opposite to structure—potentially even more so than agency (

Foucault 1982;

Butler 1997;

Morales and Harris 2014). The subject changes and transforms discourses, power relations and knowledge through the way that it understands and perceives the world or its reality (

Nightingale and Ojha 2013;

Morales and Harris 2014). Here, the reproduction or repetition of thoughts, languages and behaviours is key. Several subjects repeating one and the same idea, or one idea being repeated by a subject in a particular position of power can transform a collective discourse. Discourses are flexible, transformable and changing through the social reproduction and repetition of collective ideas.

There are a limited number of studies applying a somewhat similar framework of discourses, subjectivity, power and knowledge in the context of climate change.

Eriksen et al. (

2015) for example, use discourse, power and knowledge to illustrate how subjectivity, identity and social space may enable or constrain people’s ability to adapt to climatic changes and shocks. Adaptation strategies, or people’s adaptive behaviours, are seen as sociopolitical processes that showcase how subjects or social groups relate with one another while responding to environmental or societal changes and disruptions.

Further,

Manuel-Navarrete and Pelling (

2015) use life-story narratives around coastal adaptation strategies and hurricane risks in the Yucatan Peninsula of Mexico to understand the operations of power. Their study delicately outlines how discursive patterns shape authorities and their subjectivity. According to the findings, the politics around development and adaptation are built upon authorities that promise security and improvement in exchange for domination over the subject. Authorities are presented to the subject through the lens of binary opposites, such as underdeveloped and developed, vulnerable and self-reliant, or security and risk. This framing ends up constraining people in their decision-making process and limits their choices and freedoms—wellbeing is perceived as becoming an extension of the organisation.

4. The Order of Things: Binary Opposites or Dichotomous World Structures

The term “binary opposites” refers to the dual structuring of pairs (such as words, things or characteristics) according to the idea that everything has an opposite. In this way, people create meaning while defining things against one another, such as, for example, man–woman, body–soul, black–white, east–west and rural–urban. This builds upon the idea that people feel a “natural” need to order their reality so that the world makes sense. The system is conceptually understood as the fundamental organiser of all languages and thoughts or “the order of things” (

Foucault 1981,

2002). This refers to the way that discourses maintain or reproduce a particular system, structure or relationship of binary opposites (

Foucault 2002).

Several climate change scholars have applied the idea of binary opposites to analyse the way climate change research has been framed over the years (

Nielsen and D’haen 2014;

Baldwin 2003,

2016;

Ayeb-Karlsson et al. 2018,

2019). One of the most common binary oppositions relate to gender, and yet, surprisingly little empirical climate change research takes a gender approach. In the event of gender being introduced in climate change studies, it tends to refer to particular and “postcolonial” narratives. “Postcolonial” here refers to the continuous occurrence of colonial thought systems, hierarchies and power relations after the end of colonial rule (

Said 1978;

Spivak 1988). For example, research storylines illustrating “a poor, undeveloped, and victimised woman struggling with climate change impacts in the global south” are the most common. At the same time, empirical studies investigating structural gender vulnerabilities in relation to climate change impacts in, for example, Norway or Australia are difficult to find.

When relating this to the relative lack of people-centred decision-making within climate change research, one must ask how the lack of a gendered analysis, and its link to coloniality, shape how climate-induced (im)mobility is investigated and understood by climate change scholars. Climate-induced migration, as well as immobility, is narrated as something that happens to people, and duly noted only to certain populations in specific locations. A framework including conceptual ideas that capture discursive reproductions of binary opposites can be useful to break through these barriers. Academic climate change discourses have long been framed linguistically by climate modelers and natural or environmental scientists, while social scientists have only fairly recently started to engage with the research area (

Adger 2010;

Nielsen and D’haen 2014;

Baldwin 2016,

2017a).

Gender scholars have also expanded upon the conceptual idea that things are not only described as having “masculine and feminine” values and meaning, but that the two should also be kept apart (

Hirdman 1990;

Cornwall 2003). This may support explanations of why science (including environmental science and the study of climate change) and gender studies, for example, are described as one another’s opponents. Over time, and through social discursive reproduction, this order comes to appear “natural” or “logical”. People simply stop questioning this “order of things” as they come to perceive it as natural, static and historically founded.

Building on this,

Methmann and Rothe’s (

2014) analysis of the visualisation of climate-induced migration notes the focus on women and children from the global south as perpetuating a figure of the migrant as passive, racialised and dependent on the land—a danger (to the global north) as well as a victim. Several critical scholars have drawn attention to such images that portray climate migrants (and refugees) as passive or caring women of colour holding onto children in natural rural environments surrounded by limited belongings (

Manzo 2008;

Baldwin 2012,

2013;

Methmann and Rothe 2014). Here, it is important to critically analyse whether it is “science” alone that is being separated as a binary opposite to gender studies (as in between hard and soft data), or the gendered natural environment being detached from human psychosocial processes. The work of several critical scholars precisely touches upon binary framings of the gendered construction of nature and the environment through its relationship with the climate migrant figure. On the one hand, the climate migrant located in the global south is experiencing a masculine and aggressive war with nature and is thereby victimised or narrated as a humanitarian concern or emergency. This also helps to explain the visual overrepresentation of women and children as climate migrants. On the other hand, the climate migrant figure is also described as a potential dangerous security threat to the global north and visualised as a faceless or male moving mass, tide or flow of destructive people leaving environmental degradation and conflict behind them (

Baldwin 2012;

Trombetta 2014;

Bettini 2013,

2014;

Methmann and Rothe 2014).

In the area of climate change and human mobility, Baldwin has delicately and innovatively applied various Foucauldian-inspired concepts (such as governmentality, power and knowledge, biopower, as well as abnormality) to widen our understanding of the research area. The critical work, for example, includes investigations of forest management (

Baldwin 2003), migration and climate change (

Baldwin 2013,

2014,

2016), and climate change adaptation and resilience, including proposed climate actions such as finance schemes and insurance tools (

Baldwin 2017b).

In the analysis of the socially constructed “climate migrant”, and the power of representing this construct, Baldwin argues that “the nature of this relationship is not, however, the idea that knowledge is power, or that if one possesses knowledge then one also possesses power. It is, rather, the idea that power is exercised through the very construction of knowledge. In this sense, when one makes the claim that “climate change is a problem of migration” one is already privileging specific forms of knowledge, such as climate modelling and population distributions and dynamics, over and above, say, knowledge about the role that the sociopsychological and affective dimensions of place attachment play in migration decision making” (

Baldwin 2017a, p. 4).

It is worth mentioning that various studies have applied a conceptual framework of binary opposites and dichotomies to analyse gender relations (

Cornwall 2003;

Carr and Thompson 2014;

Detraz and Windsor 2014). One concluding idea is that the goal of this dichotomous structure is to safeguard existing power relations (such as the patriarchal system or racial hierarchies) including the power inherent in the actual order of things. It is through the structuring and separation of things that we create opposites and differences that otherwise may not have existed—they are social constructs. In this way, people end up living in a world structured in binary opposites where they are socially taught to reproduce things as masculine and feminine that must be kept apart to maintain the status quo (

Hirdman 1990;

Cornwall 2003;

Kulick 2008).

Manuel-Navarrete and Pelling (

2015) similarly conclude that top-down power relations are often presented through dichotomous subjectivities that force people into constrained choices around their positions. People are in this way made to believe that to achieve or maintain freedom and wellbeing they must become an extension of the structures of oppression and inequality that are placed upon them.

A stronger incorporation of gender, but also (other female-designated) elements such as mental health, feelings and emotions, will be crucial to better understand the human impacts of climate change. This includes the enhanced understanding of people’s responses and decision-making (such as whether to move or stay) in regard to environmental stress (

Detraz and Windsor 2014;

Ayeb-Karlsson et al. 2019,

2020). This linguistic separation or absence within the climate change literature is therefore troublesome (

MacGregor 2009;

Terry 2009;

Thompson-Hall et al. 2016). Inherent gender-structures can, for example, result in women facing stronger hardships during climate change impacts or hazards, as well as additional vulnerabilities, threats and dangers in the aftermath of a disaster or rural–urban migration (

Detraz and Windsor 2014;

Cutter 2017;

Jordan 2018;

Ayeb-Karlsson et al. 2020).

5. Discursive Decision-Making of Climate-Induced (Im)mobility and Wellbeing

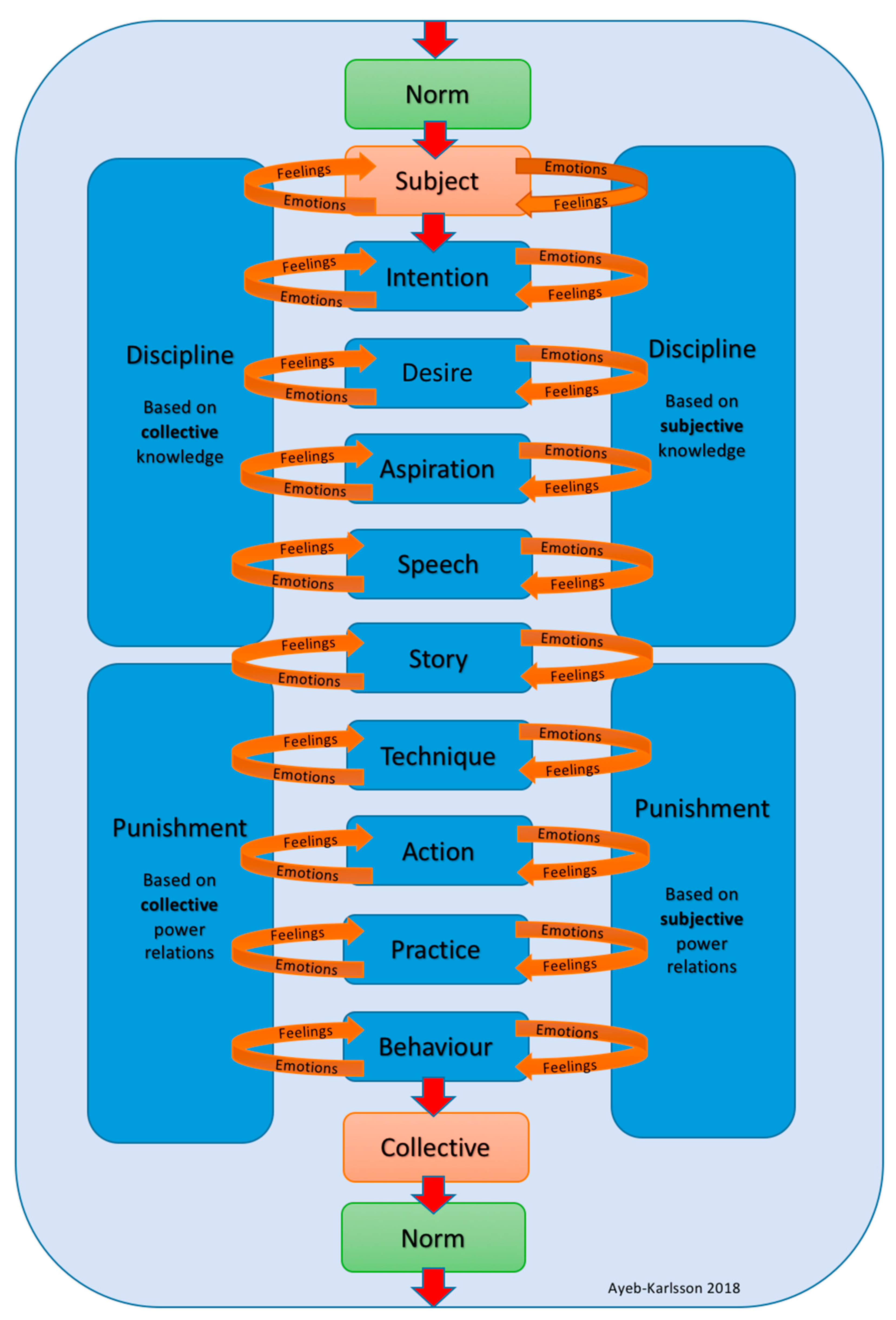

The conceptual idea introduced by this article, combining the concepts of power, knowledge, discourses, subjectivities and binary opposites, can be turned into a useful tool to further our understanding of (im)mobility decision-making and wellbeing in the context of climate change. The concepts help us to understand how discursive social norms (tied to power and knowledge) may influence people’s decision-making processes. These in turn extend to affect wellbeing. The discursive decision-making model was first presented in an empirical study investigating (im)mobility decisions and wellbeing in an informal settlement called Bhola Slum located in Dhaka (see

Figure 2), but it has also been used to understand disaster (im)mobility and wellbeing in coastal Bangladesh (

Ayeb-Karlsson et al. 2020;

Ayeb-Karlsson 2018,

2020a,

2020b). People living in Bhola Slum migrated to Dhaka from Bhola Island on the southern coast of Bangladesh in part due to environmental stress. Most participants in this research found themselves wanting to leave the slum but being unable to do so—they identified themselves as “trapped” or immobile (

Ayeb-Karlsson et al. 2020).

Findings from the

Ayeb-Karlsson (

2020a) storytelling study clearly illustrate the highly complex nature of (im)mobility decision-making. Mobility “aspirations” and “desires” do not necessarily lead to movements (or action, practice and behaviour). People explained how their feelings and emotions (linked to wellbeing) regarding normative thoughts, actions and behaviour (social discourse) guided their decision-making process and the wellbeing outcome. Discourse, power and knowledge are therefore useful concepts through which to understand the (im)mobility decision-making process. Knowledge and power enable and constrain the process through people’s discursive reality. The active social norm is reproduced and confirmed through communicative language (or speech; story; and technique, where techniques can be verbal as well as behavioural). Meanwhile, behaviour, practices and body language, including people’s observations and ideas around these social actions similarly build and reproduce discourses (

Foucault 1977,

1981,

2002;

Fairclough 2003). For example, people explained that they had ended up immobile or “trapped” as a result of a longer process. In this way, people’s immobility was not described as an experience going from mobility intention to mobility inaction. Before an idea (intention, aspiration or desire) turned into action (practice and behaviour), it would be socially challenged through communication, speech and stories. Emotions and feelings ran though all these layers that directed people into normative thoughts, decisions and behaviours.

The discursive decision-making model in

Figure 2 illustrates a conceptual idea of how decision-making and wellbeing align with discursive and social-norms through the interaction of power (e.g., punishment), knowledge (e.g., discipline), as well as feelings and emotions (

Ayeb-Karlsson et al. 2020, p. 3).

A decision was not described as a linear process going from A to Z, but as dynamic and continuously changing. In this way, respondents described sometimes desiring and even attempting migration (or initiating an action) only to return back to an aspirational migration state. People were locked into discourses regulated (subjectively and collectively) by power (punishment) and knowledge (discipline). People disciplined their migration desires and intentions based on socially normative knowledge. Similarly, in case their migration practices trespassed the discursive norm, social punishment forced them back into collectively agreed behaviours. To give an example, some of the storylines illustrated how social stigma (punishment) could constrain a person’s decision-making process and negatively affect their wellbeing. Women (often unmarried younger women) and abandoned children were particularly punished and controlled by societal norms. “Honour” was socially applied in a limiting way for women and children who did not have the same liberty to decide upon their own movements as men. Some (women and children) described how stigmatising events, such as abandonment, prevented them from returning home to Bhola Island. This stigma could extend from a father’s abandonment to mothers and children. A child could be left behind so that a woman could re-marry—the child would then face a lifetime of discrimination. Meanwhile, loss and damage to subjective wellbeing itself (or experiencing non-economic losses and damages, see, for example,

Tschakert et al. 2019) could also be immobilising or stop people from attempting to move. People described how feelings and emotions could constrain their movements—a mental paralysis trapping them in the prison of the mind (

Ayeb-Karlsson et al. 2020;

Ayeb-Karlsson 2020a). For example, collective memories of life on Bhola Island (often imaginary and not experienced) psychologically immobilised people or blocked a return move. People desired, hoped, discussed, planned and at times even managed to save up enough money to return, but still ended up staying in the slum. The desire and aspiration to move home existed, but the final decision or migration action had to wait “until things felt right”.

As observed, the discursive decision-making model can support our understanding of a range of research topics related to environmental stress and shocks, such as evacuation, adaptation, migration, and (im)mobility decisions. The conceptual idea explains how social norms, emotions and feelings can influence people’s decision-making process and their wellbeing, positively as well as negatively. This takes us to the next step regarding how the model can be used practically as a methodological approach or tool. The conceptual model has the potential to be incorporated into a study as a theoretical framework that guides diverse research methods. However, for clarity, and to facilitate practical implementation, let us elaborate the empirical examples conducted through storytelling and Q-methodology (

Ayeb-Karlsson et al. 2020;

Ayeb-Karlsson 2018,

2020a,

2020b).

The storytelling methodology can be described as an umbrella term for qualitative interviewing sessions (individual and collective) that include a storytelling component (

Pfahl and Wiessner 2007;

Ali 2013). For the empirical application of this conceptual model, diverse methods including Livelihood History Interviews (LHI), Key Experience Sessions (KES), Collective Storytelling Sessions (CSS) and Resettlement Choice Exercises (RCE) have been used to gather empirical insights (see

Ayeb-Karlsson et al. 2016,

2020;

Ayeb-Karlsson 2018,

2020a,

2020b). One of the strengths of using storytelling methodology to investigate (im)mobility decision-making and its link to wellbeing precisely relates to discursive norms. The sessions’ open and unstructured nature encourages people to lead the research storyline and change the direction of the narratives. This approach reduces researcher influence while contextualising unfamiliar values, attitudes and actions. People often feel compelled to present themselves in the best way possibly (discursive techniques based on knowledge to achieve power) which lead respondents to answer questions regarding choices made, decisions and behaviours according to what they think normatively would put them in a good light. These responses do not necessarily align with what people desired or decided to do in the end. A storytelling approach can therefore help disarm these protective boundaries and reveal values, choices and behaviours that otherwise would have been difficult to capture.

Q-methodology builds on similar disarming elements through its sorting exercise according to feelings around agreement and disagreement. Q-methodology helps capture “subjectivities”—in Q-circles understood as people’s viewpoints or attitudes of a specific place or social groups in relation to a specific topic area (

Stephenson 1935,

1986;

Brown 1980,

1996;

Stenner 2008;

Watts and Stenner 2012). The methodology (originally emerging from psychology) has been referred to as the “science of subjectivity” as it clusters individuals according to how their subjectivities reproduce a shared point of view (

Stephenson 1953). Or, as Brown describes it, “subjectivity is fundamentally a person’s point of view. It is explained as behaviour of the type that we encounter during the normal course of the day. What a person feels, conceives and perceives is a reflection of this viewpoint” (

Brown 1980, p. 46). When grouping subjectivities together, a shared way of structuring and understanding the world, a viewpoint, attitude or discourse is identified (

Dryzek 1994;

Morinière and Hamza 2012). This is also why the captured subjectivities must be understood as registered in a specific moment, place and in relation to a specific issue. It is most likely that one and the same Q-participant would present another subjectivity, or position themselves differently, in relation to another topic, or even in relation to the same topic but at a different time. A common critique of a Q-based subjectivity analysis is that it fails to explain why the participants felt and registered the Q-statements in the way they did. In an attempt to improve this, and ensure more detailed insights into people’s discursive reasoning, some Q-scholars are combining Q with discourse analysis (

Ockwell 2008;

Wolf et al. 2009;

Morinière and Hamza 2012;

Hugé et al. 2016;

Ayeb-Karlsson et al. 2020).

One of the strengths of Q-methodology is that its sorting exercise is based on the participant’s feelings and opinions, or (dis)agreement, with the proposed statements. This may decrease the level of researcher influence, or prevent respondents from giving the responses that they assume the researcher is after. The researcher’s power position in the production of knowledge must not be ignored. For example, academic research positions founded in identities, experiences and knowledge, constructed within global northern or “western modernity” will surely influence the research findings (

Said 1978;

Spivak 1988;

Manning 2018). One will never be able to fully remove these sociocultural differences, but we can and must all challenge and question these thought processes and structures. This can, for example, be achieved by encouraging elaborations around who produces or owns the specific knowledge investigated, and what type of knowledge it is that is being investigated (

Brewis and Wray-Bliss 2008;

Manning 2018).

There are a few central components supporting this conceptual framework (inspired by

Foucault 1977,

1981,

2002)—a decision is not a simple intention to action event, but a long complex process involving several steps (such as intention, aspiration, desire, action, behaviour, norm and value). An idea (intention, aspiration or desire) generally turns into action (practice, behaviour or norm) through social elaboration (communication, speech and stories). People’s emotions and feelings will be crucial elements in the decision-making process as regulators of their responses while aligning them with socially normative ideas and behaviours. This is why a decision is never straightforward or linear—people will move back and forward before reaching a decision. This may include being about to migrate only to refrain from desiring or aspiring to move. People’s decision-making processes are locked into social discourses regulated by power (including social punishment) and knowledge (including subjective discipline). In this way, the refinement of people’s decision-making takes place on a collective as well as a subjective level. Knowledge will help discipline people’s desires, aspirations and intentions according to what they believe is socially accepted. Meanwhile, power is exercised by socially punishing those who cross social norms and socially unacceptable behaviour (as well as by rewarding those who follow the social regulations).

The discursive decision-making model also aligns with the conceptual idea of binary opposites in the way that specific social roles may face particular socio-normative constraints. In other words, everyone will not be socially corrected or punished equally, nor will all subjects (or subjectivities) inherently have the same freedom to position or feel the need to discipline themselves equally. For example, the socially accepted “female” and “male” desires, intentions, actions or behaviours will not be the same. In the event of environmental stress or a natural hazard, women are often expected to care for the house and for the family members, such as children and the elderly, while men are expected to protect the household assets or family lives. This may result in women having to deal with the burden of food and water insecurity alone in the event of a drought, or even eating less as they feel that putting food on the table is their responsibility. Meanwhile, men have been reported as suffering from tremendous guilt and trauma when failing to protect or save the lives of their children in a cyclone strike (

Cutter 2017;

Jordan 2018;

Ayeb-Karlsson 2018).

The binary opposites may also extend to male behaviours being described as “active” while female behaviours ought to be “passive”. This can result in social restrictions around “female” mobility, including swimming, running and climbing trees, all very useful to survive a flood or cyclone strike. These “female” mobility constraints are also found in sociocultural traditions, such as in a South Asian regional context where women dress in a saree. A saree is a garment worn as a long piece (8 to 15 m) of cotton or silk wrapped around the body with one end draped over the head or over one shoulder. It has been reported that women’s saree or hair often becomes stuck in trees and bushes during floods, increasing their risk of drowning (

Jordan 2018;

Ayeb-Karlsson 2018).

6. Conceptual Contribution, Limitations and the Way Forward

It is important to acknowledge the differences and similarities of this proposed conceptual framework with other Foucauldian-inspired discourse analysis. This discursive decision-making conceptual idea is Foucauldian-inspired in the sense that it acknowledges the identification of discourses through the observation of practices, behaviour and actions (it is not limited to language). Discourses are conceptualised as plural, competing and complementing elements created and maintained by power and knowledge. The idea of power as a never-ending progressive or constantly transformative force tied to people’s social relations that can pose constraints as well as opportunities is also strongly Foucauldian. A range of Foucauldian-inspired discourse investigations pay attention to people’s resistance of power relations and institutionalised power fields (such as

Ansems de Vries 2016;

Odysseos 2016;

Baldwin 2017b;

Brugnach et al. 2017;

Sovacool and Brisbois 2019). Discursive power exercised through governance or political top-down processes ends up influencing people’s wellbeing in various ways. For example, the interests of power from a political economic point of view, or economic forces and their relation to law, customs, government and distribution of wealth, may be useful to widen the analytical lens of (im)mobility decision-making and subjective wellbeing.

From a political economic point of view, people’s (im)mobility decision-making, and how this relates to their vulnerabilities and wellbeing, must be aligned with the political economy of the study area. The self-identified immobile people in the urban slum of Dhaka, for example, are impoverished and “trapped” as a result of land distribution and power relations related to natural resource management. The elements that are making people want to leave the slum, such as the lack of basic infrastructure, including water, sanitation, acceptable housing, electricity and public health services, could then be understood as political strategies to push people away from the land that they are “occupying”.

Adding to this, one could also claim that non-evacuation behaviour in the event of a cyclone strike may have little to do with gender, religious beliefs or safety. Perhaps the function, location and state of the cyclone shelters rather relates to existing power dynamics. For example, schools and religious buildings are often re-used as larger cyclone shelters so that governments can avoid having to spend money on building new shelters whilst simultaneously satisfying the global requirements for disaster preparedness. Many villages therefore have functional cyclone shelters in place, but the shelters are located within village centres, such as marketplaces or central ports. If the shelters instead were to be smaller and more widespread throughout the villages more people might perhaps evacuate. People may, for example, feel safer with the shorter distances to the buildings as well as with the local crowd or close neighbours in the shelters. Further to this, perhaps non-evacuation behaviour ends up saving governments money in the longer-run as they are neither compelled to construct new shelters, nor to repair them.

In many of the investigated cyclone-affected study sites, the number of people outnumbered the shelter space. In other words, there was not enough space for everybody to evacuate if they were to choose to do so. Some people in the village had to stay behind. This takes us back to the ideas around resistance of power and the submission of power. Research findings proposing that women and children in particular stay behind, or do not evacuate, may illustrate that these vulnerable and marginalised social groups are maintaining larger power dynamics. As outlined in the conceptual idea of binary opposites, these gendered power relations are smaller mechanisms of a larger machinery. In terms of future research, more critical investigations from a bottom-up and top-down approach exploring the political and economic dynamics surrounding these issues will be important.