Polyphenols, Autophagy and Neurodegenerative Diseases: A Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism and Excretion (ADME) of Polyphenols

3. Toxicity Profile of Polyphenols

4. Autophagy and Neurodegenerative Diseases

4.1. Alzheimer’s Disease (AD)

4.2. Parkinson’s Disease (PD)

4.3. Huntington’s Disease (HD)

4.4. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS)

4.5. Multiple Sclerosis (MS)

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Aβ | Amyloid beta |

| AD | Alzheimer’s disease |

| AMPK | Adenosine monophosphate activated protein kinase |

| ALS | Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis |

| EGCG | Epigallocatechin-3 gallate |

| EAE | Encephalomyelitis |

| HD | Huntington’s disease |

| LC3 1 and 2 | Microtubule-associated protein light chain |

| mTOR | Mammalian target of rapamycin |

| PD | Parkinson’s disease |

| SNCA | Synuclein alpha |

| SOD-1 | Superoxide dismutase-1 |

| SIRT-1 | Sirtuin-1 |

| TDP-43 | TAR DNA-binding protein-43 |

References

- Tresserra-Rimbau, A.; Lamuela-Raventos, R.M.; Moreno, J.J. Polyphenols, Food and Pharma. Current Knowledge and Directions for Future Research. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2018, 156, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prabhu, S.; Molath, A.; Choksi, H.; Kumar, S.; Mehra, R. Classifications of Polyphenols and Their Potential Application in Human Health and Diseases. Int. J. Physiol. Nutr. Phys. Educ. 2021, 6, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, M.; Saeed, F.; Anjum, F.M.; Afzaal, M.; Tufail, T.; Bashir, M.S.; Ishtiaq, A.; Hussain, S.; Suleria, H.A.R. Natural Polyphenols: An Overview. Int. J. Food Prop. 2017, 20, 1689–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nirmal, J.; Babu, C.S.; Harisudhan, T.; Ramanathan, M. Evaluation of Behavioural and Antioxidant Activity of Cytisus Scoparius Link in Rats Exposed to Chronic Unpredictable Mild Stress. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2008, 8, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Saravana Babu, C.; Sathiya, S.; Anbarasi, C.; Prathyusha, N.; Ramakrishnan, G.; Kalaivani, P.; Jyothi Priya, R.; Selvarajan Kesavanarayanan, K.; Verammal Mahadevan, M.; Thanikachalam, S. Polyphenols in Madhumega Chooranam, a Siddha Medicine, Ameliorates Carbohydrate Metabolism and Oxidative Stress in Type II Diabetic Rats. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2012, 142, 331–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Goel, N. Phenolic Acids: Natural Versatile Molecules with Promising Therapeutic Applications. Biotechnol. Rep. 2019, 24, e00370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, A.; Munir, S.; Badshah, S.L.; Khan, N.; Ghani, L.; Poulson, B.G.; Emwas, A.-H.; Jaremko, M. Important Flavonoids and Their Role as a Therapeutic Agent. Molecules 2020, 25, 5243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekalu, A.; Habila, J.D. Flavonoids: Isolation, Characterization, and Health Benefits. Beni-Suef Univ. J. Basic. Appl. Sci. 2020, 9, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazza, G.; Miniati, E. (Eds.) Anthocyanins in Fruits, Vegetables, and Grains; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017; ISBN 978-1-351-06970-0. [Google Scholar]

- Kasiotis, K.M.; Pratsinis, H.; Kletsas, D.; Haroutounian, S.A. Resveratrol and Related Stilbenes: Their Anti-Aging and Anti-Angiogenic Properties. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2013, 61, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Q.; Du, R.; Liu, M.; Rong, L. Lignans and Their Derivatives from Plants as Antivirals. Molecules 2020, 25, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cory, H.; Passarelli, S.; Szeto, J.; Tamez, M.; Mattei, J. The Role of Polyphenols in Human Health and Food Systems: A Mini-Review. Front. Nutr. 2018, 5, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pérez-Jiménez, J.; Neveu, V.; Vos, F.; Scalbert, A. Identification of the 100 Richest Dietary Sources of Polyphenols: An Application of the Phenol-Explorer Database. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 64, S112–S120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bensalem, J.; Dal-Pan, A.; Gillard, E.; Calon, F.; Pallet, V. Protective Effects of Berry Polyphenols against Age-Related Cognitive Impairment. Nutr. Aging 2015, 3, 89–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rudrapal, M.; Khairnar, S.J.; Khan, J.; Dukhyil, A.B.; Ansari, M.A.; Alomary, M.N.; Alshabrmi, F.M.; Palai, S.; Deb, P.K.; Devi, R. Dietary Polyphenols and Their Role in Oxidative Stress-Induced Human Diseases: Insights into Protective Effects, Antioxidant Potentials and Mechanism(s) of Action. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, F.; Islam, M.M.; Khan Meem, A.F.; Nafady, M.H.; Islam, M.R.; Akter, A.; Mitra, S.; Alhumaydhi, F.A.; Emran, T.B.; Khusro, A.; et al. Multifaceted Role of Polyphenols in the Treatment and Management of Neurodegenerative Diseases. Chemosphere 2022, 307, 136020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makkar, R.; Behl, T.; Bungau, S.; Zengin, G.; Mehta, V.; Kumar, A.; Uddin, M.S.; Ashraf, G.M.; Abdel-Daim, M.M.; Arora, S.; et al. Nutraceuticals in Neurological Disorders. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trebatická, J.; Ďuračková, Z. Psychiatric Disorders and Polyphenols: Can They Be Helpful in Therapy? Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2015, 2015, 248529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Di Meo, F.; Valentino, A.; Petillo, O.; Peluso, G.; Filosa, S.; Crispi, S. Bioactive Polyphenols and Neuromodulation: Molecular Mechanisms in Neurodegeneration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- García-Aguilar, A.; Palomino, O.; Benito, M.; Guillén, C. Dietary Polyphenols in Metabolic and Neurodegenerative Diseases: Molecular Targets in Autophagy and Biological Effects. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabavi, S.F.; Sureda, A.; Dehpour, A.R.; Shirooie, S.; Silva, A.S.; Devi, K.P.; Ahmed, T.; Ishaq, N.; Hashim, R.; Sobarzo-Sánchez, E.; et al. Regulation of Autophagy by Polyphenols: Paving the Road for Treatment of Neurodegeneration. Biotechnol. Adv. 2018, 36, 1768–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Lorenzo, C.; Colombo, F.; Biella, S.; Stockley, C.; Restani, P. Polyphenols and Human Health: The Role of Bioavailability. Nutrients 2021, 13, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crespy, V.; Morand, C.; Besson, C.; Cotelle, N.; Vézin, H.; Demigné, C.; Rémésy, C. The Splanchnic Metabolism of Flavonoids Highly Differed According to the Nature of the Compound. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2003, 284, G980–G988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hu, B.; Liu, X.; Zhang, C.; Zeng, X. Food Macromolecule Based Nanodelivery Systems for Enhancing the Bioavailability of Polyphenols. J. Food Drug Anal. 2017, 25, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Chen, Z.; Wang, J.; Li, R.; Li, T.; Chang, M.; Yan, F.; Wang, Y. Encapsulation of Curcumin Nanoparticles with MMP9-Responsive and Thermos-Sensitive Hydrogel Improves Diabetic Wound Healing. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 16315–16326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

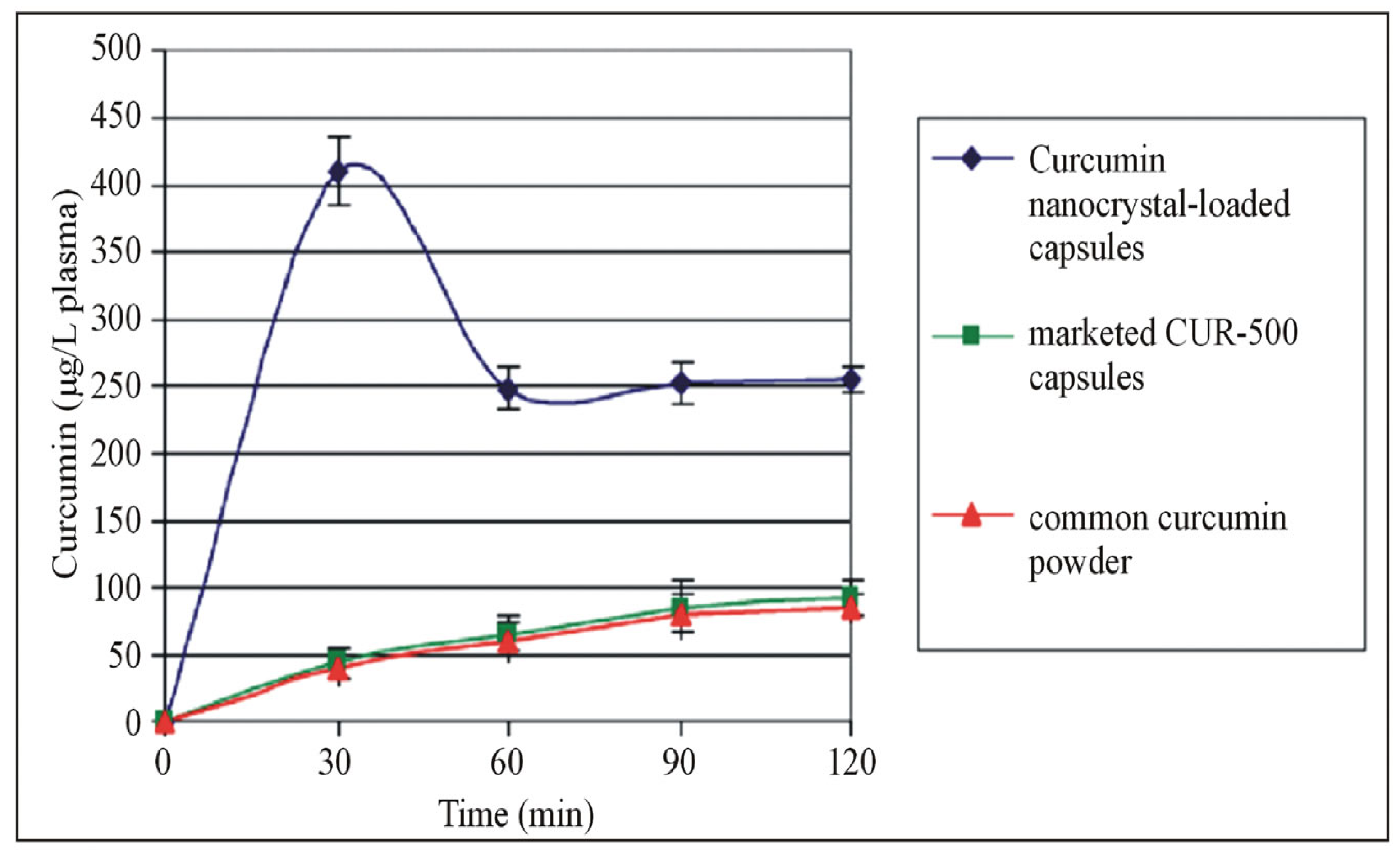

- Ravichandran, R. Pharmacokinetic Study of Nanoparticulate Curcumin: Oral Formulation for Enhanced Bioavailability. J. Biomater. Nanobiotechnol. 2013, 2013, 35329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

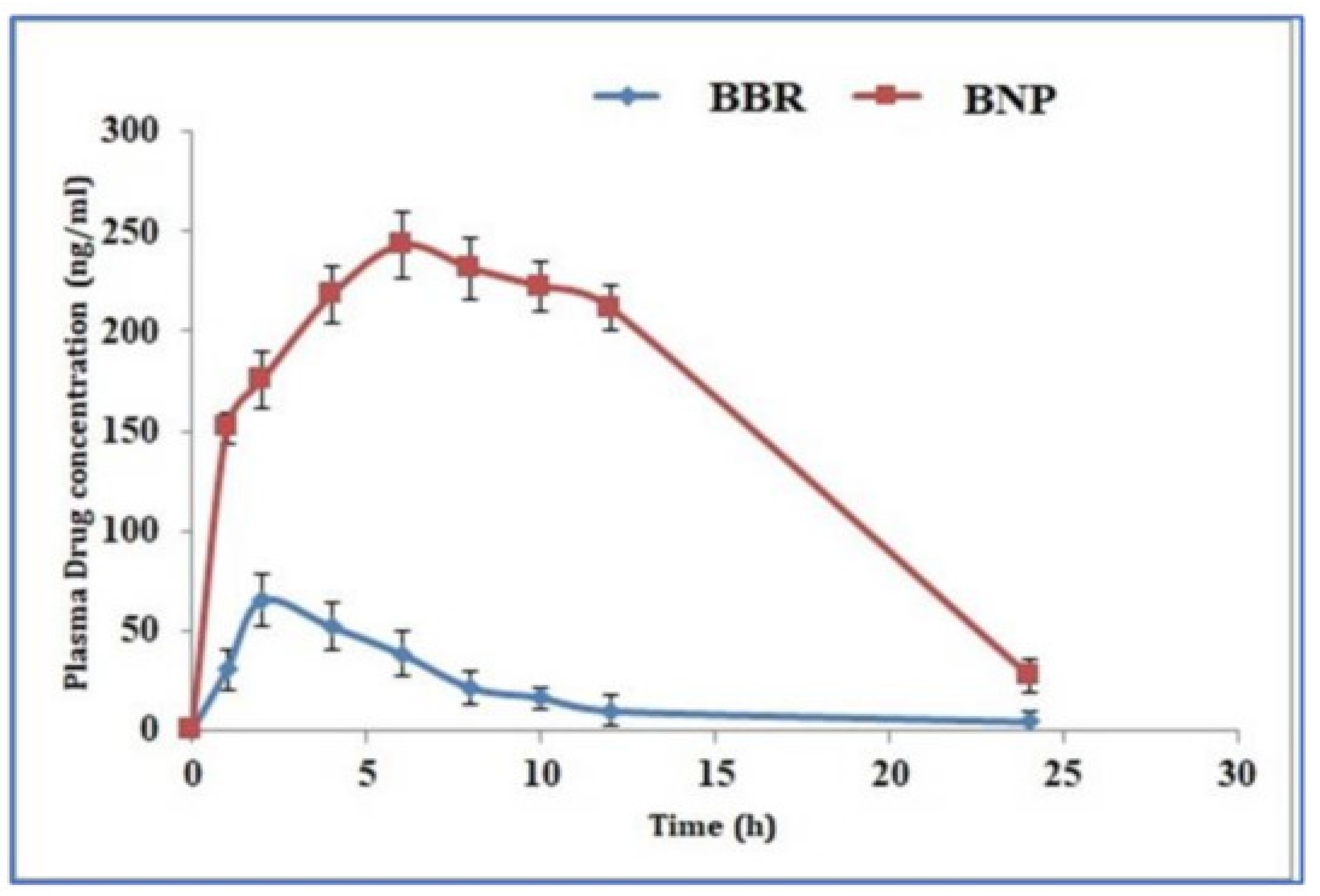

- Kohli, K.; Mujtaba, A.; Malik, R.; Amin, S.; Alam, M.S.; Ali, A.; Barkat, M.A.; Ansari, M.J. Development of Natural Polysaccharide–Based Nanoparticles of Berberine to Enhance Oral Bioavailability: Formulation, Optimization, Ex Vivo, and In Vivo Assessment. Polymers 2021, 13, 3833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasija, R.; Chaurasia, S.; Gupta, S. Assessment of Polymeric Nanoparticles to Enhance Oral Bioavailability and Antioxidant Activity of Resveratrol. Indian. J. Pharm. Sci. 2021, 83, 1114–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, N.; Mandal, A.K.A. Pharmacokinetic, Toxicokinetic, and Bioavailability Studies of Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate Loaded Solid Lipid Nanoparticle in Rat Model. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 2019, 45, 1506–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, J.D.; Sang, S.; Hong, J.; Kwon, S.-J.; Lee, M.-J.; Ho, C.-T.; Yang, C.S. Peracetylation as a Means of Enhancing In Vitro Bioactivity and Bioavailability of Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2006, 34, 2111–2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Biasutto, L.; Marotta, E.; Bradaschia, A.; Fallica, M.; Mattarei, A.; Garbisa, S.; Zoratti, M.; Paradisi, C. Soluble Polyphenols: Synthesis and Bioavailability of 3,4′,5-Tri(α-d-Glucose-3-O-Succinyl) Resveratrol. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2009, 19, 6721–6724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, P.; Lou, H. Effects of Polyphenols from Grape Seeds on Oxidative Damage to Cellular DNA. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2004, 267, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.-N.; Li, S.; Zhang, Y.-J.; Xu, X.-R.; Chen, Y.-M.; Li, H.-B. Resources and Biological Activities of Natural Polyphenols. Nutrients 2014, 6, 6020–6047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Silva, R.F.M.; Pogačnik, L. Polyphenols from Food and Natural Products: Neuroprotection and Safety. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Murakami, A. Dose-Dependent Functionality and Toxicity of Green Tea Polyphenols in Experimental Rodents. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2014, 557, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Duda-Chodak, A.; Tarko, T. Possible Side Effects of Polyphenols and Their Interactions with Medicines. Molecules 2023, 28, 2536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.; Jeong, H.; Yu, S.-W. Autophagy as a Decisive Process for Cell Death. Exp. Mol. Med. 2020, 52, 921–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordero, J.G.; García-Escudero, R.; Avila, J.; Gargini, R.; García-Escudero, V. Benefit of Oleuropein Aglycone for Alzheimer’s Disease by Promoting Autophagy. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2018, 2018, e5010741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Parzych, K.R.; Klionsky, D.J. An Overview of Autophagy: Morphology, Mechanism, and Regulation. Antioxid. Redox Signal 2014, 20, 460–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tyedmers, J.; Mogk, A.; Bukau, B. Cellular Strategies for Controlling Protein Aggregation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2010, 11, 777–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höhn, A.; Tramutola, A.; Cascella, R. Proteostasis Failure in Neurodegenerative Diseases: Focus on Oxidative Stress. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2020, 2020, e5497046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fujikake, N.; Shin, M.; Shimizu, S. Association Between Autophagy and Neurodegenerative Diseases. Front. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chidambaram, S.B.; Essa, M.M.; Rathipriya, A.G.; Bishir, M.; Ray, B.; Mahalakshmi, A.M.; Tousif, A.H.; Sakharkar, M.K.; Kashyap, R.S.; Friedland, R.P.; et al. Gut Dysbiosis, Defective Autophagy and Altered Immune Responses in Neurodegenerative Diseases: Tales of a Vicious Cycle. Pharmacol. Ther. 2022, 231, 107988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, C.G.; Lee, H.; Lee, S.B. Mechanisms of Protein Toxicity in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2018, 75, 3159–3180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chen, G.; Xu, T.; Yan, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Melcher, K.; Xu, H.E. Amyloid Beta: Structure, Biology and Structure-Based Therapeutic Development. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2017, 38, 1205–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jiang, S.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Bu, G.; Xu, H.; Zhang, Y. Trafficking Regulation of Proteins in Alzheimer’s Disease. Mol. Neurodegener. 2014, 9, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mondragón-Rodríguez, S.; Perry, G.; Zhu, X.; Moreira, P.I.; Acevedo-Aquino, M.C.; Williams, S. Phosphorylation of Tau Protein as the Link between Oxidative Stress, Mitochondrial Dysfunction, and Connectivity Failure: Implications for Alzheimer’s Disease. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2013, 2013, 940603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Long, Z.; Chen, J.; Zhao, Y.; Zhou, W.; Yao, Q.; Wang, Y.; He, G. Dynamic Changes of Autophagic Flux Induced by Abeta in the Brain of Postmortem Alzheimer’s Disease Patients, Animal Models and Cell Models. Aging 2020, 12, 10912–10930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, A.Y.; McLaurin, J. Inhibition of Amyloid-Beta Peptide Aggregation Rescues the Autophagic Deficits in the TgCRND8 Mouse Model of Alzheimer Disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2012, 1822, 1629–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ba, L.; Chen, X.-H.; Chen, Y.-L.; Nie, Q.; Li, Z.-J.; Ding, F.-F.; Zhang, M. Distinct Rab7-Related Endosomal–Autophagic–Lysosomal Dysregulation Observed in Cortex and Hippocampus in APPswe/PSEN1dE9 Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Chin. Med. J. 2017, 130, 2941–2950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossi, C.; Rigacci, S.; Ambrosini, S.; Dami, T.E.; Luccarini, I.; Traini, C.; Failli, P.; Berti, A.; Casamenti, F.; Stefani, M. The Polyphenol Oleuropein Aglycone Protects TgCRND8 Mice against Aß Plaque Pathology. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e71702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhu, Z.; Yan, J.; Jiang, W.; Yao, X.; Chen, J.; Chen, L.; Li, C.; Hu, L.; Jiang, H.; Shen, X. Arctigenin Effectively Ameliorates Memory Impairment in Alzheimer’s Disease Model Mice Targeting Both β-Amyloid Production and Clearance. J. Neurosci. 2013, 33, 13138–13149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kou, X.; Chen, N. Resveratrol as a Natural Autophagy Regulator for Prevention and Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease. Nutrients 2017, 9, 927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Qiu, W.-Q.; Pan, R.; Tang, Y.; Zhou, X.-G.; Wu, J.-M.; Yu, L.; Law, B.Y.-K.; Ai, W.; Yu, C.-L.; Qin, D.-L.; et al. Lychee Seed Polyphenol Inhibits Aβ-Induced Activation of NLRP3 Inflammasome via the LRP1/AMPK Mediated Autophagy Induction. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 130, 110575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capiralla, H.; Vingtdeux, V.; Zhao, H.; Sankowski, R.; Al-Abed, Y.; Davies, P.; Marambaud, P. Resveratrol Mitigates Lipopolysaccharide- and Aβ-Mediated Microglial Inflammation by Inhibiting the TLR4/NF-ΚB/STAT Signaling Cascade. J. Neurochem. 2012, 120, 461–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hwang, S.H.; Shin, E.-J.; Shin, T.-J.; Lee, B.-H.; Choi, S.-H.; Kang, J.; Kim, H.-J.; Kwon, S.-H.; Jang, C.-G.; Lee, J.-H.; et al. Gintonin, a Ginseng-Derived Lysophosphatidic Acid Receptor Ligand, Attenuates Alzheimer’s Disease-Related Neuropathies: Involvement of Non-Amyloidogenic Processing. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2012, 31, 207–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, H.; Chen, Q.; Zhao, B. Genistein Ameliorates Beta-Amyloid Peptide (25–35)-Induced Hippocampal Neuronal Apoptosis. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2004, 36, 180–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jowaed, A.; Schmitt, I.; Kaut, O.; Wüllner, U. Methylation Regulates Alpha-Synuclein Expression and Is Decreased in Parkinson’s Disease Patients’ Brains. J. Neurosci. 2010, 30, 6355–6359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pan, P.-Y.; Yue, Z. Genetic Causes of Parkinson’s Disease and Their Links to Autophagy Regulation. Park. Relat. Disord. 2014, 20, S154–S157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lynch-Day, M.A.; Mao, K.; Wang, K.; Zhao, M.; Klionsky, D.J. The Role of Autophagy in Parkinson’s Disease. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2012, 2, a009357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cheung, Z.H.; Ip, N.Y. The Emerging Role of Autophagy in Parkinson’s Disease. Mol. Brain 2009, 2, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ray, B.; Bhat, A.; Mahalakshmi, A.M.; Tuladhar, S.; Bishir, M.; Mohan, S.K.; Veeraraghavan, V.P.; Chandra, R.; Essa, M.M.; Chidambaram, S.B.; et al. Mitochondrial and Organellar Crosstalk in Parkinson’s Disease. ASN Neuro 2021, 13, 17590914211028364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.-H.; Tan, J.-Q.; Durairajan, S.S.K.; Liu, L.-F.; Zhang, Z.-H.; Ma, L.; Shen, H.-M.; Chan, H.Y.E.; Li, M. Isorhynchophylline, a Natural Alkaloid, Promotes the Degradation of Alpha-Synuclein in Neuronal Cells via Inducing Autophagy. Autophagy 2012, 8, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jiang, T.-F.; Zhang, Y.-J.; Zhou, H.-Y.; Wang, H.-M.; Tian, L.-P.; Liu, J.; Ding, J.-Q.; Chen, S.-D. Curcumin Ameliorates the Neurodegenerative Pathology in A53T α-Synuclein Cell Model of Parkinson’s Disease through the Downregulation of MTOR/P70S6K Signaling and the Recovery of Macroautophagy. J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2013, 8, 356–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.-K.; Chen, S.-D.; Chuang, Y.-C.; Lin, H.-Y.; Huang, C.-R.; Chuang, J.-H.; Wang, P.-W.; Huang, S.-T.; Tiao, M.-M.; Chen, J.-B.; et al. Resveratrol Partially Prevents Rotenone-Induced Neurotoxicity in Dopaminergic SH-SY5Y Cells through Induction of Heme Oxygenase-1 Dependent Autophagy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 1625–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.-J.; Dong, S.-Y.; Cui, X.-X.; Feng, Y.; Liu, T.; Yin, M.; Kuo, S.-H.; Tan, E.-K.; Zhao, W.-J.; Wu, Y.-C. Resveratrol Alleviates MPTP-Induced Motor Impairments and Pathological Changes by Autophagic Degradation of α-Synuclein via SIRT1-Deacetylated LC3. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2016, 60, 2161–2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jo, M.G.; Ikram, M.; Jo, M.H.; Yoo, L.; Chung, K.C.; Nah, S.-Y.; Hwang, H.; Rhim, H.; Kim, M.O. Gintonin Mitigates MPTP-Induced Loss of Nigrostriatal Dopaminergic Neurons and Accumulation of α-Synuclein via the Nrf2/HO-1 Pathway. Mol. Neurobiol. 2019, 56, 39–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Q.; Yang, Z.; Liu, J.; Feng, L. Caffeic Acid Reduces A53T α-Synuclein by Activating JNK/Bcl-2-Mediated Autophagy In Vitro and Improves Behaviour and Protects Dopaminergic Neurons in a Mouse Model of Parkinson’s Disease. Pharmacol. Res. 2019, 150, 104538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatoba, O.; Ohtake, Y.; Itokazu, T.; Yamashita, T. Immunotherapies in Huntington’s Disease and α-Synucleinopathies. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, L.M.; Kim, K.; Johnson, C.W.; Chen, S.; Croce, K.R.; Victor, M.B.; Eenjes, E.; Bosco, J.R.; Randolph, L.K.; Dragatsis, I.; et al. Huntington’s Disease Pathogenesis Is Modified In Vivo by Alfy/Wdfy3 and Selective Macroautophagy. Neuron 2020, 105, 813–821.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nah, J.; Yuan, J.; Jung, Y.-K. Autophagy in Neurodegenerative Diseases: From Mechanism to Therapeutic Approach. Mol. Cells 2015, 38, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shibata, M.; Lu, T.; Furuya, T.; Degterev, A.; Mizushima, N.; Yoshimori, T.; MacDonald, M.; Yankner, B.; Yuan, J. Regulation of Intracellular Accumulation of Mutant Huntingtin by Beclin 1. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 14474–14485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wong, V.K.W.; Wu, A.G.; Wang, J.R.; Liu, L.; Law, B.Y.-K. Neferine Attenuates the Protein Level and Toxicity of Mutant Huntingtin in PC-12 Cells via Induction of Autophagy. Molecules 2015, 20, 3496–3514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pérez-Arancibia, R.; Ordoñez, J.L.; Rivas, A.; Pihán, P.; Sagredo, A.; Ahumada, U.; Barriga, A.; Seguel, I.; Cárdenas, C.; Vidal, R.L.; et al. A Phenolic-Rich Extract from Ugni Molinae Berries Reduces Abnormal Protein Aggregation in a Cellular Model of Huntington’s Disease. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0254834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Wei, W.; Gaertig, M.A.; Li, S.; Li, X.-J. Therapeutic Effect of Berberine on Huntington’s Disease Transgenic Mouse Model. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0134142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, P.; Dargusch, R.; Bodai, L.; Gerard, P.E.; Purcell, J.M.; Marsh, J.L. ERK Activation by the Polyphenols Fisetin and Resveratrol Provides Neuroprotection in Multiple Models of Huntington’s Disease. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2011, 20, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vidoni, C.; Secomandi, E.; Castiglioni, A.; Melone, M.A.B.; Isidoro, C. Resveratrol Protects Neuronal-like Cells Expressing Mutant Huntingtin from Dopamine Toxicity by Rescuing ATG4-Mediated Autophagosome Formation. Neurochem. Int. 2018, 117, 174–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasinelli, P.; Brown, R.H. Molecular Biology of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: Insights from Genetics. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2006, 7, 710–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arai, T.; Hasegawa, M.; Akiyama, H.; Ikeda, K.; Nonaka, T.; Mori, H.; Mann, D.; Tsuchiya, K.; Yoshida, M.; Hashizume, Y.; et al. TDP-43 Is a Component of Ubiquitin-Positive Tau-Negative Inclusions in Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration and Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2006, 351, 602–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanekura, K.; Suzuki, H.; Aiso, S.; Matsuoka, M. ER Stress and Unfolded Protein Response in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Mol. Neurobiol. 2009, 39, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brenner, D.; Weishaupt, J.H. Update on Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Genetics. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2019, 32, 735–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crippa, V.; Sau, D.; Rusmini, P.; Boncoraglio, A.; Onesto, E.; Bolzoni, E.; Galbiati, M.; Fontana, E.; Marino, M.; Carra, S.; et al. The Small Heat Shock Protein B8 (HspB8) Promotes Autophagic Removal of Misfolded Proteins Involved in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS). Hum. Mol. Genet. 2010, 19, 3440–3456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, L.; Zhang, N.; Fan, D. Protective Effects of Resveratrol through the Up-Regulation of SIRT1 Expression in the Mutant HSOD1-G93A-Bearing Motor Neuron-like Cell Culture Model of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Neurosci. Lett. 2011, 503, 250–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Choi, J.-R.; Soon Shin, K.; Kang, S.J. Resveratrol Upregulated Heat Shock Proteins and Extended the Survival of G93A-SOD1 Mice. Brain Res. 2012, 1483, 112–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancuso, R.; del Valle, J.; Modol, L.; Martinez, A.; Granado-Serrano, A.B.; Ramirez-Núñez, O.; Pallás, M.; Portero-Otin, M.; Osta, R.; Navarro, X. Resveratrol Improves Motoneuron Function and Extends Survival in SOD1G93A ALS Mice. Neurotherapeutics 2014, 11, 419–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ueda, T.; Inden, M.; Shirai, K.; Sekine, S.-I.; Masaki, Y.; Kurita, H.; Ichihara, K.; Inuzuka, T.; Hozumi, I. The Effects of Brazilian Green Propolis That Contains Flavonols against Mutant Copper-Zinc Superoxide Dismutase-Mediated Toxicity. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 2882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, J.; Duan, W.; Guo, Y.; Jiang, H.; Li, Z.; Huang, J.; Hong, K.; Li, C. Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Human TDP-43 Transfected NSC34 Cell Lines and the Protective Effect of Dimethoxy Curcumin. Brain Res. Bull. 2012, 89, 185–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.H.; Wang, S.Y.; Wang, X.D.; Jiang, H.Q.; Yang, Y.Q.; Wang, Y.; Cheng, J.L.; Zhang, C.T.; Liang, W.W.; Feng, H.L. Fisetin Exerts Antioxidant and Neuroprotective Effects in Multiple Mutant HSOD1 Models of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis by Activating ERK. Neuroscience 2018, 379, 152–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobson, R.; Giovannoni, G. Multiple Sclerosis—A Review. Eur. J. Neurol. 2019, 26, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Interplay between ER Stress and Autophagy: A Possible Mechanism in Multiple Sclerosis Pathology. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 2019, 108, 183–190. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Misrielal, C.; Mauthe, M.; Reggiori, F.; Eggen, B.J.L. Autophagy in Multiple Sclerosis: Two Sides of the Same Coin. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2020, 14, 603710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igci, M.; Baysan, M.; Yigiter, R.; Ulasli, M.; Geyik, S.; Bayraktar, R.; Bozgeyik, İ.; Bozgeyik, E.; Bayram, A.; Cakmak, E.A. Gene Expression Profiles of Autophagy-Related Genes in Multiple Sclerosis. Gene 2016, 588, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albert, M.; Barrantes-Freer, A.; Lohrberg, M.; Antel, J.P.; Prineas, J.W.; Palkovits, M.; Wolff, J.R.; Brück, W.; Stadelmann, C. Synaptic Pathology in the Cerebellar Dentate Nucleus in Chronic Multiple Sclerosis. Brain. Pathol. 2017, 27, 737–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Patergnani, S.; Castellazzi, M.; Bonora, M.; Marchi, S.; Casetta, I.; Pugliatti, M.; Giorgi, C.; Granieri, E.; Pinton, P. Autophagy and Mitophagy Elements Are Increased in Body Fluids of Multiple Sclerosis-Affected Individuals. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2018, 89, 439–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyao, Y.; Mengjiao, S.; Caicai, B.; Xiaoling, L.; Zhenxing, L.; Manxia, W. Dynamic Expression of Autophagy-Related Factors in Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis and Exploration of Curcumin Therapy. J. Neuroimmunol. 2019, 337, 577067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dierckx, T.; Haidar, M.; Grajchen, E.; Wouters, E.; Vanherle, S.; Loix, M.; Boeykens, A.; Bylemans, D.; Hardonnière, K.; Kerdine-Römer, S.; et al. Phloretin Suppresses Neuroinflammation by Autophagy-Mediated Nrf2 Activation in Macrophages. J. Neuroinflamm. 2021, 18, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.-R.; Zhang, X.-J.; Liu, H.-C.; Ma, W.-D.; Zhang, M.-L.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Dou, M.-M.; Jing, Y.-L.; Chu, Y.-J.; et al. Matrine Protects Oligodendrocytes by Inhibiting Their Apoptosis and Enhancing Mitochondrial Autophagy. Brain Res. Bull. 2019, 153, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Deng, R.; Jing, X.; Chen, J.; Yang, D.; Shen, J. Acteoside Ameliorates Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis through Inhibiting Peroxynitrite-Mediated Mitophagy Activation. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2020, 146, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chandrasekaran, V.; Hediyal, T.A.; Anand, N.; Kendaganna, P.H.; Gorantla, V.R.; Mahalakshmi, A.M.; Ghanekar, R.K.; Yang, J.; Sakharkar, M.K.; Chidambaram, S.B. Polyphenols, Autophagy and Neurodegenerative Diseases: A Review. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 1196. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom13081196

Chandrasekaran V, Hediyal TA, Anand N, Kendaganna PH, Gorantla VR, Mahalakshmi AM, Ghanekar RK, Yang J, Sakharkar MK, Chidambaram SB. Polyphenols, Autophagy and Neurodegenerative Diseases: A Review. Biomolecules. 2023; 13(8):1196. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom13081196

Chicago/Turabian StyleChandrasekaran, Vichitra, Tousif Ahmed Hediyal, Nikhilesh Anand, Pavan Heggadadevanakote Kendaganna, Vasavi Rakesh Gorantla, Arehally M. Mahalakshmi, Ruchika Kaul Ghanekar, Jian Yang, Meena Kishore Sakharkar, and Saravana Babu Chidambaram. 2023. "Polyphenols, Autophagy and Neurodegenerative Diseases: A Review" Biomolecules 13, no. 8: 1196. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom13081196