1. Introduction

Mexico (

Estados Unidos Mexicanos) is a large country, uniquely situated in North America, where it shares borders with the United States of America to the north and with two Central American countries, Guatemala and Belize, to the south. It covers an area of approximately 2 million square kilometers (the 13th largest country in the world), with a population of about 125 million people of which 51.1% are women and 48.9% are men (

(Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía) INEGI 2018). The majority of the country’s population now resides in urban areas, with only 22.2% living in rural areas, compared to 1950 when 54.6% of the population resided in rural communities (

INEGI 2010a). It has 32 states, with Mexico City being the federal state where governmental power and functions are situated. Article 2 of Mexico’s Constitution describes the nation as pluricultural, owing its diversity to Indigenous peoples, the original inhabitants of the land before Spanish colonization. In addition to Spanish, Mexico boasts of 68 Indigenous languages as its national languages, with Nahuatl and Maya being the most spoken (

INALI 2012). The languages of the Indigenous peoples are enshrined in the 2003 General Law of Linguistic Rights of Indigenous Peoples (

Ley General de Derechos Lingüísticos de los Pueblos Indígenas). The Law also created the National Institute of Indigenous Languages (Instituto Nacional de Lenguas Indígenas (INALI)), a decentralized organization of the Federal Public Administration, under the Secretary of Culture, which promotes, preserves, revitalizes and researches Indigenous languages.

The proportion of the Mexican population that speaks an Indigenous language has been in steady decline for many years, starting from 16% in 1930 and decreasing to 6.6% by 2015 (

INEGI 2015). The majority of Indigenous language speakers also speak Spanish. The languages with the highest proportion of monolingual speakers are Tzotzil (30.8%) and Tzeltal (29.8%) (

INEGI 2015). Currently, 21.5% of Mexico’s population self-identity as Indigenous (

INEGI 2015). The Indigenous population is an increasingly young one, with 58% being younger than 30 years old, which is 5% higher than the national average (

(la Comisión Nacional para el Desarrollo de los Pueblos Indígenas) CDI 2016). Approximately half of the 364 varieties of Indigenous languages in Mexico are at some risk of endangerment: 64 varieties are in critical danger of disappearing, 43 are in severe danger, 73 are at medium risk and the remaining 185 are considered safe for now (

INALI 2012).

The phenomenon of endangerment facing Indigenous languages is not unique to Mexico but is a global one. Linguists estimate that at least half of the world’s 7000 languages will be endangered in a few generations, as they are no longer being spoken as first languages (

Hale et al. 1992;

Austin and Sallabank 2011). The majority of these endangered languages are Indigenous languages. For example, less than 10% of Indigenous languages in the United States will be spoken by 2050 (

National Congress of American Indians 2016); about 16% of the Indigenous population in Canada speak an Indigenous language (

Statistics Canada 2017); and at least 20% of the 640 diverse Indigenous groups or peoples are no longer speaking their languages in Latin America (

Haboud et al. 2016).

Investigating the causes of language endangerment has increasingly become a topic of interest for educators, anthropologists, linguists, and other researchers. A major cause of the endangered status of many Indigenous languages can be traced back to the history of colonization, which spurred on the banning and eradication of Indigenous languages. The destructive assimilationist linguistic policies of the colonial period were adopted by governments and executed with the assistance of schools and/or churches. Mexico, Canada, the United States, and countries in South America established residential or boarding schools aimed at destroying the languages and cultures of Indigenous youth under the guise of integrating them into mainstream society (

Dawson 2012). The continuing negative effects of residential schools extend beyond language and culture to health care, child welfare, criminal justice, education, and economic development (

United States Commission on Civil Rights 2018). Survivors have reported receiving severe abuse for speaking their languages and as a result they stopped speaking their languages and transmitting them to younger generations (

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada 2015). This “cultural genocide”, to use the words of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, enforced the negative stereotypes and associations with Indigenous languages, harming their maintenance and intergenerational transmission. Indigenous languages are often associated with backwardness, poverty, and racism (

Knockwood 2015;

Haboud et al. 2016). Furthermore, speakers of Indigenous languages and other threatened languages face enormous pressure to switch to the dominant languages because of the numerous political, social and cultural advantages that the latter have (

Barreña et al. 2007;

Skutnabb-Kangas 2015). Languages such as Spanish in the Latin American context are used at international levels in trade, exchange of ideas, and policy and at national levels in education, mass media, work, and official and government-related matters (

Eberhard et al. 2021) while most Indigenous languages are limited to informal use. Even when there is legislation that mandates that Indigenous languages be used in schools, they are rarely used as the language of instruction (

Haboud et al. 2016;

Olko and Sullivan 2014,

2016). In addition to repressive assimilationist policies, negative attitudes, and social and economic motivations, other factors facilitating language endangerment include lack of official support, insufficient funding and infrastructure, lack of interest or commitment, intergenerational trauma or shame, natural disasters, and man-made disasters, such as war and genocide (

Nettle and Romaine 2000;

Crystal 2000;

Barreña et al. 2007;

McCarty et al. 2006;

Jenni et al. 2017;

Chambers 2014;

Delaine 2010;

McIvor 2015;

McIvor and Anisman 2018).

The issue of language endangerment has attracted the attention of researchers, linguists, activists, communities, governments, and multinational organizations, such as the United Nations, as it is increasingly perceived as an issue of human rights, not merely a linguistic matter. There have been many activities and projects at the local, national, and international levels to safeguard and revitalize Indigenous languages ranging from language documentation, language courses or programs, to enactment of language laws and policies enshrining the linguistic rights of Indigenous peoples. Examples of such laws are the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) (

United Nations 2007) at the global level and the 2003 General Law for the Linguistic Rights of Indigenous Peoples in the national Mexican context. The Canadian government passed an Indigenous Language Act in 2020 to strengthen and maintain Indigenous languages in the country. Many countries in Latin America including Peru, Brazil, and Paraguay have enacted legislation recognizing the linguistic rights of Indigenous peoples. They recognize their use in Indigenous territories (e.g., Belize, Guyana), mandate the state to protect linguistic diversity and identity (e.g., Argentina, Costa Rica), recognize their official status (e.g., Bolivia, Ecuador), and treat them as a cultural and national heritage (e.g., El Salvador, Guatemala). While legislation does not necessarily translate into effective implementation and practical application to ensure the revitalization and maintenance of Indigenous languages, it is an important step which at least guarantees the legal status of these languages.

Researchers are encouraged to adopt a community-based participatory approach when working in Indigenous communities where mutual trust is built, partnership established, and power shared between them and Indigenous communities (

Ritchie et al. 2013;

Christopher et al. 2011). Such an approach allows for the utilization of Indigenous ways of knowing, interpretation of data within a cultural context and the understanding of diversity (

LaVeaux and Christopher 2009). Research granting agencies also look to support research projects with impact both inside and outside academe. Additionally, there are several organizations that promote and support the cause of endangered Indigenous languages such as the Foundation for Endangered Languages, Living Tongues Institute for Endangered Languages, First Peoples’ Cultural Council, SIL International, National Science Foundation, and UNESCO.

2. Language Shift and Maintenance

Research on language endangerment has examined the factors or pressures deterring or facilitating the maintenance of languages. Several scales have been developed to measure the degree of endangerment of languages and/or predict language shift based on a variety of factors (

Gomashie and Terborg 2021). Some of these scales used at the global level include the Graded Intergenerational Disruption Scale (GIDS) (

Fishman 1991), the Language Vitality and Endangerment (LVE) framework (

Brenzinger et al. 2003), the Expanded Graded Intergenerational Disruption Scale (EGIDS) (

Lewis and Simons 2010) and the Catalogue of Endangered Languages (ELCat) (

Endangered Languages Project 2012). The factors for assessing language health or vitality include the absolute number of speakers, speaker number trends, language domains of use, intergenerational transmission, language attitudes, language policies, age of the speaker population, geographical distribution of language, availability of materials for education and literacy, and the amount or quality of documentation.

Of all the factors, intergenerational transmission is considered the most important (

Fishman 1991;

Brenzinger et al. 2003). Studies which have focused on the causes of language shift of Indigenous languages in Mexico have found that a decrease in intergenerational transmission of these languages is one of the main causes (

Terborg and García Landa 2011,

2013). Some parents are no longer teaching their Indigenous language to their offspring, resulting in children who no longer speak it as their first language (

Crystal 2000). Some parents may express positive attitudes towards Indigenous languages and consider them as part of the cultural pride and heritage, such as Quechua-speaking parents in Peru in

Hornberger’s (

1988a) study, but do not transmit them to their children. A study on Indigenous languages in Alaska found that while citizens expressed the desire for the preservation of their language and culture, they may not be willing to fully commit themselves to the process (

Dauenhauer and Dauenhauer 1998). Language activists and educators heavily involved in organizing workshops to advocate for the inclusion of Indigenous languages in schools and other domains of use sometimes do not transmit them to their children (

Messing 2003). Positive language attitudes and even passionate language advocacy do not always correlate with language use and transmission. In some situations, the lack of interest on the part of the younger generations has been cited as one of the reasons for language shift (

McCarty et al. 2006;

King 2000). Adults sometimes blame the younger generations for not being committed enough to learn the language in spite of their efforts (

Gal 1979;

Kulick 1992). In addition, research has shown that the peer group of a child or an adolescent can influence language use and attitudes (

Caldas 2012). Children can also influence the language use of their parents: for example, Zapotec-speaking parents in Los Angeles felt pressured by their children to communicate in English as the children did not want to speak Zapotec (

Pérez Báez 2013).

Parents or adults often do not transmit their language because they prefer their children to gain fluency in the dominant language before acquiring their Indigenous language so that their children do not mix or ‘confuse’ both languages. In a study of Quichua-speaking parents in the Saraguro communities of Tambopamba and Laguna in Ecuador,

King (

2000) found that most parents would not communicate in Quichua with their children because they feared it would hamper their Spanish development. For them, proficiency in Spanish had to be acquired first before any Indigenous language learning was considered. The global myth that one’s mother tongue, minoritized languages, or bilingualism is a hindrance to a child’s academic success has existed for many years. Unfortunately, this belief is not only held by parents and mainstream society but also by some educators (

Taylor 2014;

Kupisch and Rothman 2018). This attitude towards language mixing also speaks to some prevailing attitudes in Indigenous communities which are purist in nature where any form of mixing is frowned upon, which may discourage less proficient speakers (

Hansen 2010). Another reason that most Indigenous parents in Mexico prefer that their children learn Spanish is their belief that Spanish will be more beneficial to their children since it is necessary for socioeconomic advancement and professional development. This feeds into the global discourse of language as a commodity (

Heller 2003;

Smala et al. 2013) where adults, especially parents, want their children or the younger generations to learn languages they consider more useful in terms of career or economic prospects. Apart from the utilitarian value that Spanish has in Mexico as the de facto national language, it is also one of the most spoken languages in the world. When comparing the usefulness of learning a global language like Spanish with Indigenous languages, the latter appear to have little value for speakers beyond personal, communal and traditional use (

Hill and Hill 1986;

Messing 2007;

Hansen 2010).

Another factor deterring the language maintenance of Indigenous languages in Mexico involves mainstream negative attitudes which do not provide a conducive environment for Indigenous peoples to use their language outside of their community. In some communities, such negative attitudes may be internalized by speakers, resulting in some speakers denying knowledge of their language, much less transmitting it to the younger generations (

Brenzinger et al. 2003;

Messing 2007;

Jenni et al. 2017). Legislation does not eradicate negative stereotypes and associations with Indigenous languages. For example, while the General Law recognized Indigenous languages as national languages along with Spanish, no Indigenous language has reached institutional level status in Mexico.

Hornberger (

1988b) found that some Quechua speakers denied having any knowledge of the language due to a sense of shame and a desire to integrate into the Spanish-dominated broader society. They believed that to be fully integrated into society, it was necessary to deny or minimize one’s knowledge of Quechua. Speakers of Indigenous languages face discrimination and racism based on their language, a concept that

Skutnabb-Kangas (

1988,

2015) refers to as linguicism. In Mexico, the teaching of Indigenous languages is not supported financially to the same extent as Spanish, the medium of instruction in schools. Indigenous language programs in Mexican schools have only achieved limited success. While the government has instituted bilingual and intercultural education at the pre- and basic-school levels in Indigenous communities, there are several issues regarding its implementation and infrastructure that impede its effectiveness. For instance, the Indigenous languages are rarely used as languages of instruction. Even when they are taught as a subject, Spanish is still the language of instruction. The textbooks used, usually commissioned by the Ministry of Education, are sometimes written using another variety, different from that of the community. There have been situations where Indigenous-language-speaking teachers have been placed in communities with a different variety from what they speak. All these challenges have facilitated a language shift to Spanish. Indigenous languages are often associated with tradition and culture on one hand and backwardness and poverty on the other, while Spanish is associated with modernity and progress. With the decline in the use of Indigenous languages among the younger generations, they are increasingly becoming languages used predominately by adults.

Having reviewed some of the causes of language shift and maintenance which touched on several factors such as intergenerational transmission, language attitudes of adults, children/adolescents and society, and governmental support, the present study focuses on language use, another important factor in assessing the vitality of a language. In order to gain a fuller appreciation of the status of an Indigenous language in a bilingual setting, it is valuable to examine language use in a variety of spheres or domains. The Council of

Europe (

2001) identifies four main domains of language use: personal (related to an individual’s private life and interactions with family and friends); public (associated with an individual’s communication with the general public); occupational (work-related); and educational. The following section reviews previous literature on Indigenous language use, with a major emphasis on the use of Nahuatl.

3. Indigenous Language Use

An example of a detailed study on the domains of language use is

Rubin’s (

1968) seminal study on Paraguayan bilingualism, which investigated language use during 1960–1961 in the rural–urban town of Luque near Asunción, the capital. She examined interactions in the family (personal), community (public), work (occupational), market (public), academic (educational), and affective (personal and public) contexts. The main findings were that while the Indigenous language, Guaraní, was associated with intimate (e.g., family), informal (e.g., friends), and less serious (e.g., jokes) contexts, Spanish was associated with formality (e.g., communications with teacher, boss, priest, and doctor), prestige, education, and socioeconomic value.

Choi’s (

2005) comparative study done 40 years later (2000–2001) found that several changes had occurred in language use in Luque. There was a displacement of Guaraní in all linguistic contexts, especially in intimate and informal ones, in favor of bilingual use or Spanish. However, Guaraní made inroads in the educational system after bilingual schooling was introduced in the country.

Choi (

2005) reported a shift towards bilingualism and an increase in the use of Spanish in urban areas, a prediction made by

Rubin (

1968). The language use questionnaires employed for both studies in Paraguay were adapted for the present project.

There are additional studies centered on other themes such as language ideologies or attitudes that provide information on Indigenous languages. An example is

Hornberger’s (

1988b) study which explored adult language attitudes towards Spanish and Quechua in Puno, Peru through interviews found that while some devalued Quechua, others valued it and expressed loyalty to it. There was a general appreciation for multilingualism where both languages were considered necessary. Spanish was valued for its immense socioeconomic and communicative advantages in mainstream society but it was noted that the inaccessibility of Spanish learning materials required that they spend extra effort in learning it. Community members preferred Quechua for interacting in informal, private, humorous, and communal settings. Quechua was the language which represented solidarity and intimacy for community members. In the Totonac-speaking Upper Nexaca Valley of Mexico, parents preferred to communicate in Spanish with children because of its associated socioeconomic opportunities. Studies on other Indigenous languages, such as Cora, Mazahua, Otomí, Matlatzinca, Atzinca, and Mixe, in Mexico have also reported that the younger generation generally preferred to use Spanish in their interactions in their family circle, but used Indigenous languages most frequently with their grandparents (

Trujillo Tamez et al. 2007;

Pérez Alvarado et al. 2018;

Gómez-Retana et al. 2019). In the Canadian context, the remote Cree and Algonquin communities in Quebec communicated more in their Indigenous languages at home and in their community while Mohawk communities close to Montreal employed English in most language domains (

Norris 2004;

Gomashie 2019). In all the studies reviewed above, the general conclusion is that the use of Indigenous languages is primarily reserved for use in the home, with families, and in the community; that is for informal, private, and communal interactions. Although the younger generations generally prefer to use the dominant language such as English or Spanish, they use their Indigenous languages with their grandparents. In the following subsection, studies on Nahuatl language use are reviewed.

Studies on Nahuatl Language Use

Census data are a valuable resource to track the number of speakers of Indigenous languages, although they do not provide information on the contexts of language use. According to 2010 national census, Nahuatl is the most spoken Indigenous language in Mexico with over 1.5 million speakers, aged 5 and older. Nahuatl speakers are found in highest numbers in the states of Puebla, Hidalgo, Guerrero, San Luis Potosi, and Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave. Nahuatl has 30 varieties, and half of these are considered to be at immediate risk of disappearing (

INALI 2012). Most Nahuatl speakers are bilingual, with only 7% being monolinguals (

INEGI 2015).

Figure 1 shows the percentage distribution of the Nahuatl-speaking population from 1990 to 2010 for five age groups (5–14, 15–24, 25–34, 35–44, and 45 and older). Two demographic shifts are evident over the 20-year period represented in this Figure. First, the proportion of Nahuatl speakers in the 5 to 14-year-old group decreased from 27% to 19%. According to

INALI (

2012), one of the main criteria for a language to be considered safe is for its youngest speakers (ages 5 to 14) to make up at least 25% of the speaker population. Nahuatl is currently below this critical level, suggesting that intergenerational transmission of the language is impaired. Second, the proportion of Nahuatl speakers in the oldest age group (45 and older) increased from 24% to 32% over this 20-year period. This follows the general trend that in Indigenous communities facing language endangerment, the older speakers continue to use the language, while the youngest generation exhibits a decline in language use. The three intermediate age groups (15–24, 25–34, 35–44) did not show any significant changes in their proportions of the Nahuatl-speaking populations over time. The Nahuatl variety under study in this project, Northern Puebla variety, is spoken in the Acaxochitlán municipality in the state of Hidalgo, and eleven municipalities in Puebla, namely Chiconcuautla, Honey, Huauchinango, Jopala, Juan Galindo, Naupan, Pahuatlán, Tlaola, Tlapacoya, Xicotepec, and Zihuateutla (

Valiñas 2019). It is one of the varieties considered to be at no immediate risk of endangerment (

INALI 2012). In the community of Santiago Tlaxco, 83% of the population, aged 5 and older, speak Nahuatl while 76% are bilinguals who speak both Spanish and Nahuatl (

INEGI 2010b).

There have been some small-scale studies which have reported on Nahuatl use, although the language use was not the primary theme of the research.

Hill and Hill’s (

1986) seminal research in eleven Nahuatl-speaking towns in the Malintzi region of Tlaxcala-Puebla in Central Mexico found that Nahuatl was preferred for interactions in domestic and informal contexts and used in expressing kinship and emotional ties. Spanish was preferred for communication in public, impersonal, and formal settings. Two decades later,

Messing (

2007,

2009) found similar patterns of use in two towns, Contla and San Isidro, in the same region studied by

Hill and Hill (

1986). Other studies that primarily focused on Nahuatl language use in the home context noted that elders were very integral to transmitting Nahuatl to the younger generation (

Gómez-Retana et al. 2019;

Mojica Lagunas 2019;

Hansen 2016;

Garrido Cruz 2015;

Hill 1998). A recent study (

Gomashie 2020a) examining language practices of young people (aged 12–17) inside and outside their homes in Santiago Tlaxco revealed that they primarily communicated in Nahuatl with their grandparents, in line with findings of previous studies. At home, most of them preferred to communicate in Spanish with their siblings and in both Spanish and Nahuatl with their parents and other relatives. Outside the home and among the peers, they used both languages mostly with their male friends and school colleagues, but mostly Spanish with their female friends. They used Spanish with professionals like doctors, nurses and teachers on one hand, and strangers on the other. Even when expressing emotions, they preferred to use either only Spanish or both languages. The language that individuals use to communicate emotions or feelings tends to be the language they feel most comfortable with (usually their first language) or most expressive in, most linguistically competent in, or has the most emotional resonance for them (

Dewaele 2010). For young people, Nahuatl was the least preferred linguistic option. The absence of an exclusive context for Nahuatl use, except with grandparents, highlights a shift towards Spanish. While young people generally expressed positive attitudes towards Nahuatl such as its importance to the community, its inclusion in schools, and its aesthetic beauty, these attitudes did not translate to actual use. Some attributed the low usage of Nahuatl to their own linguistic insecurity in the language due to a lack of desired proficiency, a preference for Spanish as the more socioeconomically viable language, and internalized negative attitudes of community members. This foundational study on language practices of young people in Santiago Tlaxco sets the stage for the current project to describe the language patterns of adults who form the parent and grandparent generations of the community, the principal agents of language transmission. These studies contribute to much-needed knowledge on Nahuatl language vitality in Mexico. The current study adds novel information by exploring the use of Nahuatl by adults with multiple interlocutors in different contexts. To our knowledge, such a study has not been done before. Our project used a similar survey approach as the landmark study by

Rubin (

1968) and its replicated study (

Choi 2005) that examined language use of Guaraní and Spanish in the bilingual context of Paraguay.

6. Discussion

The aim of this study was to examine the language practices of adults in the bilingual context of Santiago Tlaxco to provide insight into the vitality of the Nahuatl language in the community. The results to the research question, “what are the language use patterns of adults in Santiago Tlaxco?”, were presented in three main areas: (a) the home or family circle, an important site for intergenerational transmission and language maintenance; (b) the community, a reflection of collective language use; and (c) emotional states, which provide insight into the languages with which individuals feel the most comfortable. Additionally, the results for the total adult population in each main area are followed by the group presentation results. Beginning with the results in the home environment, Nahuatl was the language of choice in the family circle, an indication that its language maintenance is still ongoing. However, parents preferred to use both Nahuatl and Spanish with their children younger than 13 years of age. Examination of the group results shows that there were more differences than similarities in the language patterns of use between the younger adults (aged 18–40) and older adults (aged 41–78). While the older adults preferentially used Nahuatl with all family members, the younger adults preferred to use it only with their siblings, parents, and grandparents. The younger group predominately adopted a bilingual approach in communicating with their spouse, children of all ages, and other relatives. For the purpose of language maintenance, an interesting finding is language use with children or future generations, who would be replacing the (grand)parent generations. From the results, there is a shift from Nahuatl language use with children among the older adults to a trend of bilingualism among younger adults. This finding is consistent with that of

Gomashie (

2020a) where the youth (aged 12–17) in the same community reported using both languages most frequently with their parents. This finding is different from the Guaraní studies where Spanish was the preferred option for communicating with children (

Rubin 1968;

Choi 2005).

The shift towards bilingualism in the community suggests some possibilities, such as parents being supportive of bilingualism or believing that Nahuatl should not be learned exclusively. There is support for both possibilities from a study of language attitudes in the same community (

Gomashie 2020b). Several studies have shown that adult or parental beliefs are an important factor in language transmission (

Hill and Hill 1986;

Messing 2007,

2009;

Pérez Báez 2013;

Caldas 2012;

King et al. 2008). In Santiago Tlaxco, adults generally supported bilingualism and wanted the younger generations to learn both languages. However, some parents reported that they preferred that their children gain proficiency in one language first, usually Spanish, before acquiring Nahuatl. Parents often wanted their children to learn Spanish first for easier transition to the educational system where Spanish is the language of instruction. This is one of the most common themes in Indigenous communities worldwide, where parents want their children to learn the dominant language because their own past experience with their language (

Messing 2007;

King 2000). For example, parents did not transmit their Indigenous language because they had a hard time transitioning to the Spanish-language schooling system (

Lam 2009;

Olko and Sullivan 2016) or the English-language schooling system (

Knockwood 2015). It should be noted that while Tlaxco has both a pre-school and a basic school which are supposed to be bilingual and intercultural, Nahuatl is seldom used as the language of instruction. Other reasons for wanting children to learn Spanish first are its representation as the language of socioeconomic opportunities, professional development and advancement, and wider communication. Many Indigenous communities grapple with the reality that their languages are not considered economically viable. For some speakers, their Indigenous languages are associated with poverty and social stagnation (

Knockwood 2015;

Skutnabb-Kangas 2015;

Haboud et al. 2016).

Not knowing the dominant language, be it Spanish or English, makes it very difficult for persons to integrate into mainstream society. Lack of proficiency in Spanish deprives Indigenous peoples of socioeconomic opportunities such as a salaried job (

Hill and Hill 1986) as Spanish is the functional language in most contexts including official and government domains.

Skutnabb-Kangas (

2015) criticizes this type of discrimination against Indigenous peoples based on their language, which forces them to prioritize the dominant language. Given the situation of Spanish dominance in Mexico, it is no surprise that parents’ reports of bilingual usage with their children do not necessarily represent equal use of both languages. An extreme example illustrating this point was one father who reported on the questionnaire that he used both languages with his children (ages 12 and 17) but when interviewed he revealed that his occasional usage of Nahuatl with his 12-year-old daughter only involved translating some Nahuatl words into Spanish whenever she was curious about them. Despite this minimal use of Nahuatl with his daughter, this father selected the option “both languages” on the questionnaire to describe his language use with her. Thus, while bilingualism was commonly reported by adults in Tlaxco, it may often be unequal bilingualism, favoring Spanish more than Nahuatl. This is more apparent when we consider that irrespective of age, the younger age group used both languages with their children while the older age group preferred to use Nahuatl.

The current results on community language use show that Nahuatl was generally preferred by the majority of the total adult population in public settings outside the home context. It was the language of choice in interactions with neighbors, friends in the neighborhood, workmates, employees, boss, curanderos, clergy, adults, and elders in the community. This finding is encouraging for language maintenance as it shows that Nahuatl language use extended outside the family circle and was dominant in most community contexts. The use of Nahuatl with friends and neighbors is a positive factor as one’s social circles and immediate surroundings can influence language choice (

Caldas 2012). The preferred use of Nahuatl in the work sphere with colleagues, employees, and employers, contrasts with the Guaraní studies where Spanish was the language of choice with one’s boss (

Rubin 1968;

Choi 2005). Most community members in Tlaxco were involved in agricultural work inside, or outside, the community. When they worked outside the community, they sometimes traveled together with their Nahuatl-speaking co-workers from the community. In the place of worship, Nahuatl was generally used with the priest or pastor due to the language skills of the clergymen who are Nahuatl speakers, except the Catholic priest. Nahuatl being mostly used in communication with adults and the elderly while both languages were used with infants, children, and adolescents, suggests that Nahuatl use was mainly reserved for adults. This assessment agrees with the results of

Gomashie (

2020a) which showed that the young people (less than 18 years) in Tlaxco preferred to use either Spanish or both languages for interactions in the community. Mojica

Lagunas (

2019) also reported a similar trend where the youth, out of respect for elders, were reluctant to speak Nahuatl and felt that the language should be spoken when they grow older and become more responsible. Other young people were reluctant to speak Nahuatl with elders because they thought they lacked adequate fluency. Groupwise, patterns of Nahuatl language use in the community were generally similar between the younger and older adults, except in interactions with the youth: the older group preferred to use Nahuatl, while the younger group used both languages. The consistently more frequent use of Nahuatl by the older group in many contexts highlights the importance of elders or grandparents in fostering language maintenance (

Hill 1998). This outcome is consistent with other studies (

Garrido Cruz 2015;

Hansen 2016;

Gómez-Retana et al. 2019;

Mojica Lagunas 2019) where adults, especially seniors, are the gate keepers of Nahuatl. Similar to Guaraní-speaking Luque, Spanish was predominately used in formal situations, especially with professionals, such as schoolteachers, doctors, and nurses, as they were usually not from the community. Additionally, Spanish was commonly used in unfamiliar situations, such as with strangers. In the market, the use of both languages was preferred.

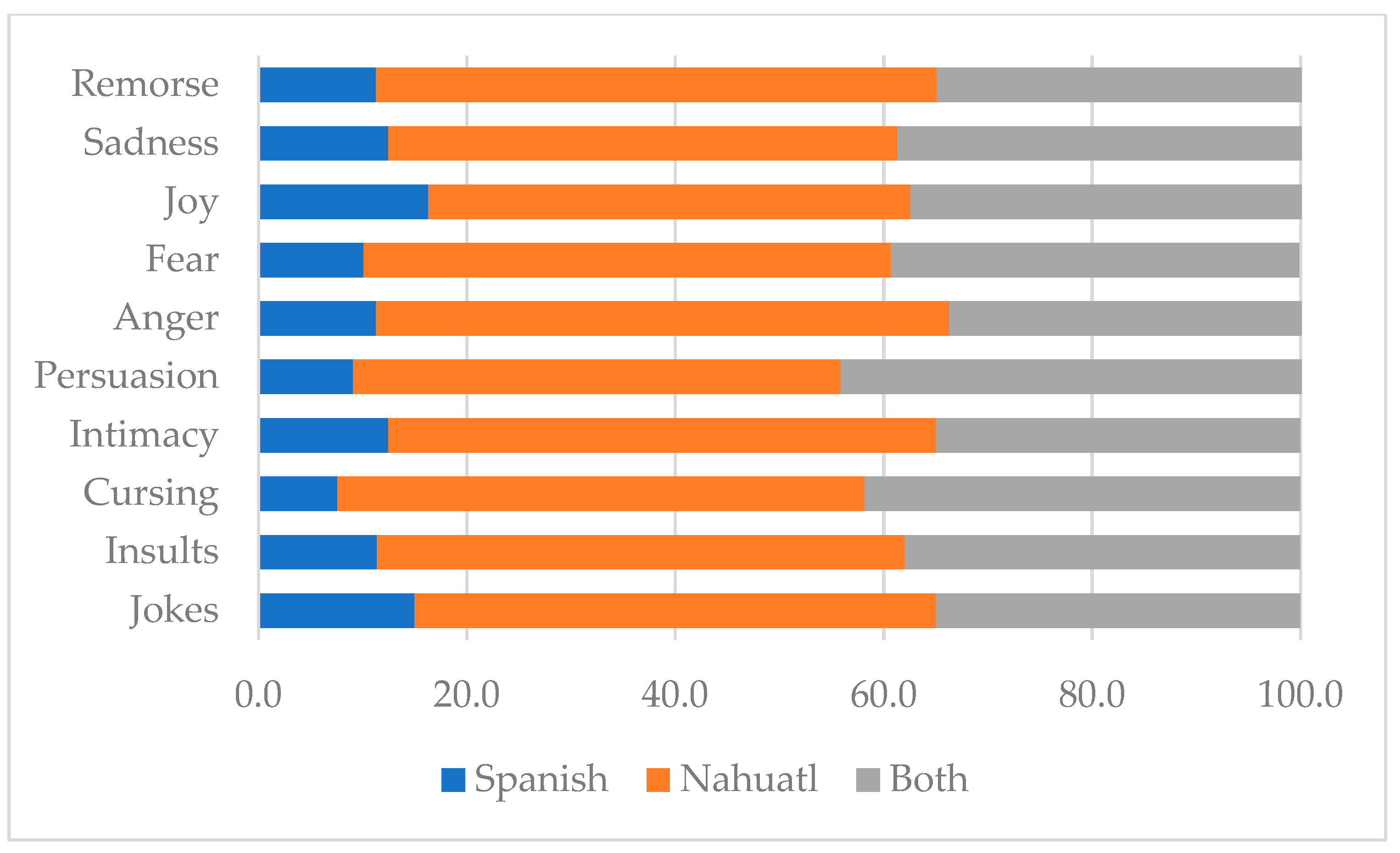

Another finding was that Nahuatl was used most commonly in emotional states. This result underlines that Nahuatl is the language with which adults are most comfortable. These findings are consistent with other studies (

Hill 1998;

Garrido Cruz 2015;

Hansen 2016;

Gómez-Retana et al. 2019;

Mojica Lagunas 2019) However, when the adult population was divided into two age groups, there was a noticeable difference in the language use patterns. While older adults preferred Nahuatl in the expression of emotions as did Guaraní speakers in the 1960s (

Rubin 1968), there was a trend towards bilingualism among younger adults similar to Guaraní speakers in the 2000s (

Choi 2005). This result is particularly interesting when compared to that of the youth in the community who predominately used Spanish for emotions (

Gomashie 2020a). It gives a snapshot of a community where the youth is most comfortable in Spanish, the younger adults in both languages, and the older adults in Nahuatl.

The current results from Santiago Tlaxco have significance for language maintenance of Nahuatl, both safe and endangered varieties, across Mexico. With only 7% of the national Nahuatl population being monolingual and Nahuatl communities such as Santiago Tlaxco increasingly becoming bilingual, community members make language choices and decisions while navigating their own personal language attitudes, beliefs, experiences, and expectations, along with child language preferences, mainstream attitudes and societal myths. Endangered Nahuatl varieties grapple with the disruption of intergenerational transmission, resulting in fewer child speakers and a shift to Spanish language use in the home and in other community contexts. Apart from the negative attitudes towards Nahuatl such as its perceived lack of usefulness outside the community, its supposed barrier to child language development in Spanish, racism and discrimination, and negative linguistic experiences, the shift to Spanish in these communities is also fueled by the socioeconomic and communicative benefits associated with the latter. Even safe varieties of Nahuatl are not immune to these factors causing language shift. Santiago Tlaxco is a cautionary example for the long-term maintenance of other safe Nahuatl varieties. Our data show a downward trajectory in Nahuatl use across generations, with the oldest generation preferring Nahuatl use, the middle generation preferring bilingual use, and the youngest generation preferring to use Spanish. This assessment is in the line with census data which confirm at a national level that Nahuatl use in young people is declining, while its use is sustained among the older generations. It also highlights the older generations as the bedrock of Nahuatl language maintenance. As in Tlaxco, bilingual Nahuatl families at a national level have to be more purposeful in the transmission of the language to their children. The family language policy (that is the language use, language beliefs, and language planning) of most Nahuatl households tends to be spontaneous, unplanned or unconscious, which favors the use of Spanish, the majority and most dominant language in Mexico. Spanish, considered the more socioeconomically viable language, is the medium of education, mass media, wider communication, and government or official matters. This provides opportunities and motivation for children to learn and speak Spanish whereas the same level of infrastructure and support system does not exist for Nahuatl. Parents, family and other community members become primarily responsible for transmitting Nahuatl to children and incentivizing them to learn and use the language. As stakeholders, community members who are aware of the important role they play in the maintenance and revitalization of Nahuatl (endangered or safe) may be encouraged to have a family language policy which also considers Nahuatl acquisition. In the final section of this paper, I outline how the findings of this study could impact language maintenance and planning efforts for Nahuatl and other Indigenous languages across Mexico and elsewhere.

8. Implications for Language Planning

The present study sought to establish the status or vitality of Nahuatl language, an important first step for any language planning or maintenance project. It provides information on the speaker population, language usage, and language domains, which are some of the ways of assessing language status. Other ways of assessing language status include exploring the language attitudes of both community members and the general public to assess support for an Indigenous language and its maintenance. The current study assists language planners to identify who are speaking Nahuatl, where Nahuatl is spoken, and the areas in need of support. It also assists them in identifying available resources for Nahuatl language maintenance. For example, the older adults in Santiago Tlaxco who are fluent speakers represent the human and cultural resources necessary for language maintenance, as they frequently use the language in many aspects of their daily lives. However, this community lacks technical, material, financial, institutional and documentation resources for Nahuatl language revitalization.

After any Indigenous or linguistic community project conducts this primary step of determining the status of the language, the next step involves mobilizing community support. Grassroots community support for language maintenance is key to the success of language maintenance efforts and should be sought from the initial stage of any linguistic project and throughout the whole process. Language planners in collaboration and consultation with community members, leaders, and stakeholders may come up with the next steps in maintaining or revitalizing their language such as setting the language priorities and goals, determining effective strategies to accomplish these goals, and participating in and implementing projects. Activities include brainstorming with community members, recruiting them to participate in the language plan, interviewing and surveying them for their input, and sharing and discussing survey results with them.

Setting language goals is an opportunity for the community to express what they desire for their language in terms of proficiency levels, role of the language inside and outside the community, language use for future generations, and language values or importance for the community. Based on the current results for Santiago Tlaxco, some of the language goals set by the community could include encouraging adults, especially fluent speakers, to commit to speaking Nahuatl with their children, families, and other community members. Another could be to encourage young people to use Nahuatl more, to take ownership of language learning, and to feel affinity with or pride in their language. For some communities, the goals could be to increase the speaker population, expand the language domains beyond the traditional context of the home, increase literacy and proficiency levels in the language, foster cultural prestige and identity in the language, create a positive language environment, promote the language inside and outside the community, seek more visibility in the media and linguistic landscape, and create more documentation such as dictionaries, grammars, educational resources, stories, and narratives. Other Indigenous communities may choose to focus on the culture, traditions, and value systems of the community. For example, an Indigenous community could set a goal to collect cultural expressions of the community for dissemination and archival purposes, with the aim of raising the cultural awareness of its members and preserving their traditions. The collection of cultural expressions could cover proverbs, myths, jokes, riddles, folktales, songs, poetry, legends, and superstitious beliefs.

Accompanying each step of a language plan with research will yield a well-planned project. Research is necessary to discover what has already been and/or can be done in the community, and what can be learned from what other communities have done to support language use and revitalization. For Santiago Tlaxco, there has been no previous language study in the community, apart from census data collection. This opens opportunities for research collaboration with community members, linguists, researchers, universities, and organizations to develop language maintenance and revitalization activities. Postsecondary institutions can also do more to support Nahuatl including training local linguists and developing degree and diploma granting programs in Nahuatl. They could also be involved in teaching Nahuatl at the early childhood and pre-secondary levels, transferring their expertise on language learning and teaching, curriculum development, and language teaching materials. There is also an opportunity for the community to set up a language planning council in charge of coordinating and promoting language activities in the home, schools, and community. Currently, there is an organization, La UNTI México, dedicated to the translation of Spanish religious texts into Indigenous languages, which is collaborating with community members in Santiago Tlaxco to translate religious materials into the Northern Puebla variety of Nahuatl. This documentation project will provide an important resource for this Nahuatl variety which lacks a standardized literature.

Communities can initiate language projects in line with their set goals and priorities to ensure more language use. The community may decide to undertake an immersion program, training project, documentation project, curriculum development project, or promotion project. Should a community opt for any educational project, it can tap into the available resources such as a pool of fluent speakers in the case of Santiago Tlaxco. These elders are not only an important repository of language and cultural knowledge but also provide a point of reference for language queries, especially in Indigenous communities where speakers do not usually acquire their languages through the medium of schools. The input of fluent speakers is also necessary in producing new speakers outside the home environment. Language revitalization programs, such as language nests, immersion for adults and children, and mentor–apprentice programs also benefit from the inclusion or input of fluent speakers. A documentation project may seek to create digital resources for language learning. Indigenous communities can collaborate with educational software programmers to set up digital learning platforms or environments. In this way, opportunities are created to take Indigenous language learning to a literacy level. It should be as convenient to learn Indigenous languages as it is for other widely spoken languages. The development of electronic learning platforms creates a new space of language use for Indigenous languages, such as Nahuatl.

Therefore, determining the language status of an Indigenous community by means of questionnaires and surveys is the foundation of any language planning project which assists the community to identify its unique language needs and develop the appropriate solutions to address them. Documenting Nahuatl language use and domains in the current study is an important first step that provides useful information for future language planning.