Novel Spaces as Catalysts for Change: Transformative Learning through Transnational Projects

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- Developing changemakers;

- Social innovation education;

- The use of innovative digital learning environments including virtual and artificial reality technologies.

- Using immersive reality to develop exergames combating the link between videogaming and physical inactivity.

- Exchanging 360-degree films of environmental challenges between countries and suggesting prototype solutions.

- Exploring digital tools to enhance communication in the face of rising sea levels eroding geographical boundaries.

2. Research Questions

- How do undergraduate education students reflect on their experiences of novel spaces in an international project?

- Do novel spaces support transformative learning in undergraduate education students in an international project?

3. Literature Review

3.1. The Role of Novel Spaces in Transformative Learning

3.2. Disorientation and Transformation

3.3. Physical and Virtual Novel Spaces

3.4. Transformation, Travel and Novel Spaces

3.5. Reflective Novel Spaces

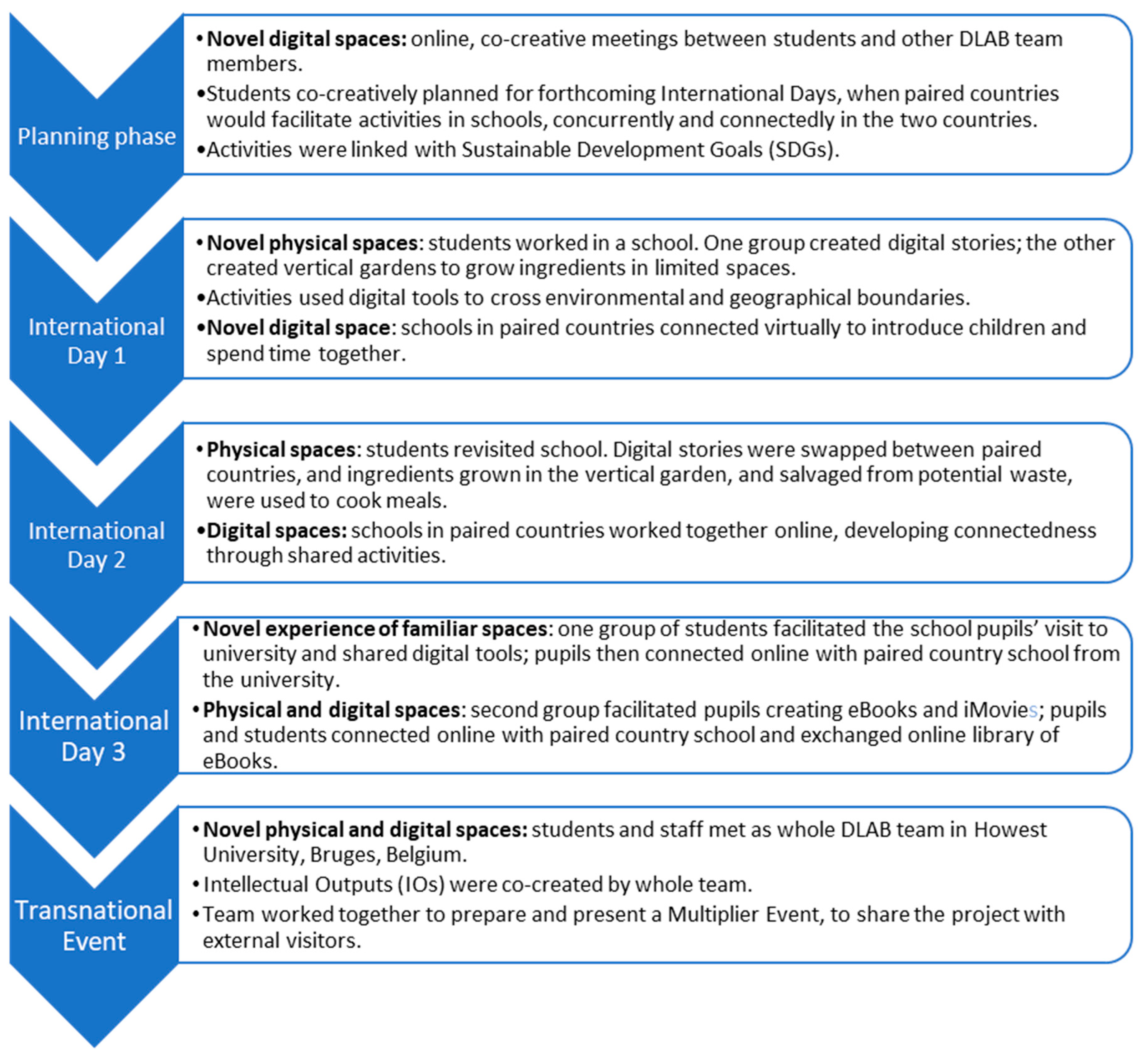

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Methods

4.2. Interview Process

- How did you feel about your involvement in the project right at the start?

- How did you feel about being involved during the international days?

- How did you contribute to the project personally?

- What skills have you personally developed through the project?

- What impact could this experience have on your future practice?

- How do you feel about your involvement now?

- Have any of your feelings changed?

4.3. Written Reflections

4.4. Ethical Considerations

4.5. Data Analysis

5. Results

5.1. Theme 1: Enjoyment

‘I enjoyed it personally, because we got to be involved and do the things as well [alongside the children’], that it was new to me […] that’s everything you really want really, so I mean, from me it was really good.’ (Participant 6i).

‘It’s so lovely to see all the other students from, like, the other groups as well and see what they’ve been doing. And also, because with Norway, we were doing zoom calls with them....so to actually meet in person and actually have a conversation with them [face to face] was so nice.’ (Participant 7i).

‘I’ve really enjoyed working with the children, […] with other countries. And it’s something that we’ve never experienced before.’ (Participant 5i).

‘I really enjoyed how we got to, like, call the other class from Norway and speak to them, and the children got to speak to each other [too]. I thought that was a good idea.’ (Participant 4i).

5.2. Theme 2: Challenges

‘Some parts were slightly stressful...especially the laptops–not having [enough] laptops, the laptop batteries dying.’ (Participant 3i).

‘But then sort of when the technology wasn’t working, you could see that they [the children] started to lose interest and get distracted or didn’t want to do... so like if it didn’t work we had to do it on paper.’ (Participant 5i).

‘I think we were a bit confused at first, but as it went on, I think we got better. I think I was nervous...but then once we, like, got involved and did the first international day, yeah it was really good.’ (Participant 3i).

‘It was a bit frustrating that there was a lack of communication between us and the students as we really wanted to be more engaged.’ (Participant 1 and 2w).

5.3. Theme 3: Developing Skills

‘Like any workplace or anything you go to, you’re gonna have to work with different people.’ (Participant 7i).

‘We were expecting all students to speak English, on arrival this was the expectation from all countries. However, as students attending an international event, we [now realise that we] should have been more open-minded and ready to learn new languages and communication skills.’ (Participant 4w).

‘The opportunity to expand [my] skills in multiple ways...learning to speak in front of new people, working with students in a different culture and workspace, and participating ethically in personal intercultural settings.’ (Participant 4w).

‘...as we did not understand the children’s native language we needed to communicate with them in English, but making sure we were clear so the children could understand us.’ (Participants 4 and 5w).

‘We ensured that we explained things in simple, easy terms and spoke clearly. We also made sure our body language was approachable by smiling at the children and not having our arms folded to look as approachable as possible as body language crosses language barriers.’ (Participants 4 and 5w).

‘I think it’s really good because I do want to work with children when I’m older, so [it was good practice]. like just being thrown in the deep end kind of thing.’ (Participant 5i).

‘Just gaining more experience as much as you can in a different way. Because there’s probably never going to be another chance to do something like this.’ (Participant 5i).

‘Often when in new situations and meeting new people, I lose confidence and will often let other people speak for me. So, this event was an opportunity for me to expand my cultural competence and interact more confidently with a range of different people.’ (Participant 3i).

‘Leadership, maybe as well, kind of taking on roles being able to be like ‘oh, I’ll help them with this [...]’ So, you have to be organised, you need to know what you’re doing. Like prioritise things and be able to actually build a rapport with people.’ (Participant 7i).

‘There’s a lot more technology out there than I knew, like today, I did the Scavengar app. I wouldn’t have even known like, that was a thing. And I really liked Book Creator. But I didn’t know that was a thing before.’ (Participant 3i).

5.4. Theme 4: Widening Perspectives

‘There’s probably never going to be another chance to do something like this.’ (Participant 5i).

‘This DLAB trip to Bruges gave me the opportunity to expand my skills in multiple ways learning to speak in front of new people, working with students in a different culture and workspace, and participating ethically in personal intercultural settings.’ (Participant 3i).

‘It was something that all of the children had never done before and it was something really exciting and new for them. And for us as well.’ (Participant 5i).

‘From doing a project like this, you kind of look at it in different ways now, when you think of different solutions, and how... kind of gives you a bigger picture of the world [It was] really eye opening.’ (Participant 5i).

‘Developing confidence and more confidence and like more adaptability, they’re key things for later in life. It’s like a lot we can take away that will help us whether that’s in education or personal life or anything.’ (Participant 5i).

‘And if we just change certain things, it would make the world a better place.’ (Participant 2i)

‘Using everything that we’ve put together for the international days... is literally how I would go about probably my future work.’ (Participant 7i).

‘How you would go about most tasks in like a workplace is that you’d have to plan it, then you’d come back and then you’d look at everything that you’ve done, is it to the quality that you want it to be?’ (Participant 7i).

‘This experience was really eye-opening...we needed to communicate with them in English, but making sure we were clear so the children could understand us.’ (Participants 4w and 5w).

‘Be able to actually build a rapport with people so that you are like happy in your workplace as well....being able to be interested in what you’re doing and feeling like confident that you know, what you’re doing will then help you achieve more.’ (Participant 7i).

‘Developing confidence and more confidence and like more adaptability, they’re key things for later in life. So just sort of life skills.’ (Participant 5i).

‘The international trip has allowed me to learn more about both myself and being able to meet new people and learn about their cultures.’ (Participant 1w).

‘During our free time we were able to go out and explore by ourselves. This allowed me to view the city as well as the culture both during the day and the night.’ (Participant 1w).

‘We saw an array of cultural locations and buildings of importance. [...] The boat had a tour guide, who explained the cultural aspects of the place, spoke in two languages to make the trip as culturally diverse as possible.’ (Participant 4w).

‘This experience has allowed me to see how differently I now view experiencing new cultures when [I] first visit a new country as well as meeting new people.’ (Participant 1w).

‘Very enlightening and has allowed me to develop my cultural competence.’

‘It’s so lovely to see all the other students from, like, the other groups as well and see what they’ve been doing.’ (Participant 1w).

‘This DLAB trip to Bruges gave me the opportunity to expand my skills in multiple ways… learning to speak in front of new people, working with students in a different culture and workspace, and participating ethically in personal intercultural settings.’ (Participant 4w).

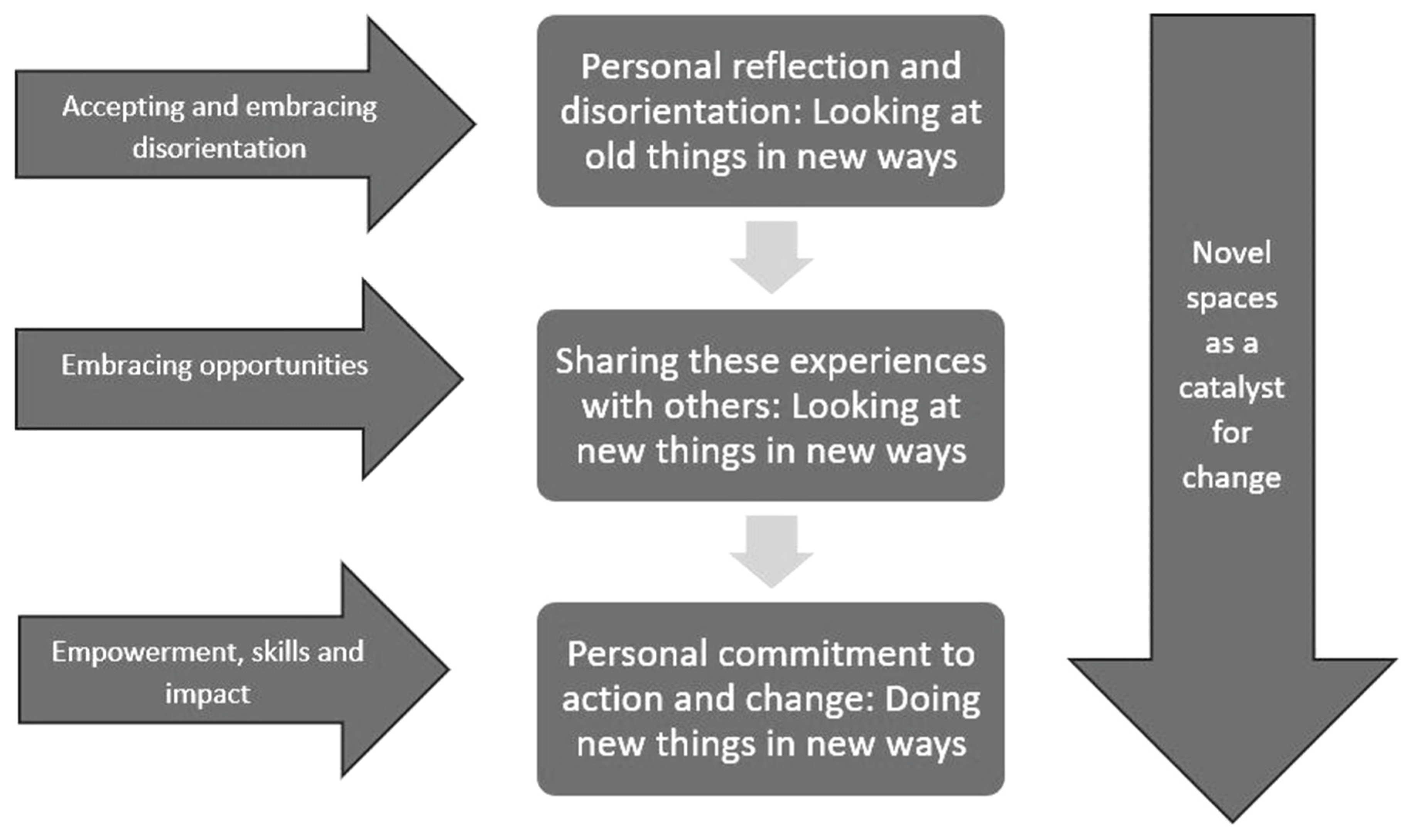

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

- In shaping work-ready graduates, we recommend:

- Recognising the interconnectedness of physical and digital spaces and how technology can facilitate agile movement between them.

- Cultivating an environment for synchronous and asynchronous intercultural exchanges.

- Building a spiral of personal development through a series of culturally rich connected experiences that ultimately lead to transformative learning.

- Nurturing the development of changemaker attributes that combine empathy for others with the motivation to solve problems through creative action [1].

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Whewell, E.; Caldwell, H.; Frydenberg, M.; Andone, D. Changemakers as digital makers: Connecting and co-creating. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2022, 27, 6691–6713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Formenti, L.; Hoggan-Kloubert, T. Transformative learning as societal learning. New Dir. Adult Contin. Educ. 2023, 177, 105–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calleja, C. Jack Mezirow’s conceptualisation of adult transformative learning: A review. J. Adult Contin. Educ. 2014, 20, 117–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezirow, J. Transformative learning theory. Contemporary Theories of Learning: Learning Theorists. In Their Own Words, 2nd ed.; Illeris, K., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2006; pp. 114–128. [Google Scholar]

- Whewell, E.; Theinert, K.; Cox, A. Sharing practice in an international context—A critique of the benefits of international exchanges for trainee teachers. East. Eur. J. Transnatl. Relat. 2020, 4, 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation. Five Questions on Transformative Education. 2023. Available online: https://www.unesco.org/en/articles/five-questions-transformative-education (accessed on 16 July 2023).

- United Nations. Sustainable Development Goals Goal 4 Quality Education. Sustainable Development Goals (SDG 4). 2023. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal4 (accessed on 2 August 2024).

- Schnepfleitner, F.M.; Ferreira, M.P. Transformative learning theory—Is it time to add a fourth core element? J. Educ. Stud. Multidiscip. Approaches 2021, 1, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitchenham, A. The Evolution of John Mezirow’s Transformative Learning Theory. J. Transform. Educ. 2008, 6, 104–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezirow, J. Transformative Dimensions of Adult Learning; Jossey-Bass: San Fransisco, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Washburn, A. Whither transformative education? Taking stock well into the twenty-first century. J. Transform. Educ. 2021, 19, 306–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitchford, A.; Owen, D.; Stevens, E. A Handbook for Authentic Learning in Higher Education: Trans-Formational Learning through Real World Experiences; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- King, H. Learning spaces and collaborative work: Barriers or supports? High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2016, 35, 158–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leijon, M.; Nordmo, I.; Tieva, Å.; Troelsen, R. Formal learning spaces in Higher Education—A systematic review. Teach. High. Educ. 2022, 29, 1460–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, A.D. Journeys into transformation: Travel to an “other” place as a vehicle for transformative learning. J. Transform. Educ. 2010, 8, 246–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinchliffe, G.W.; Jolly, A. Graduate identity and employability. Br. Educ. Res. J. 2011, 37, 563–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swist, T.; Kuswara, A. Place-making in higher education: Co-creating engagement and knowledge practices in the networked age. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2016, 35, 100–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valiente-Riedl, E.; Anderson, A.; Banki, S. Practicing what we teach: Experiential learning in higher education that cuts both ways. Rev. Educ. Pedagog. Cult. Stud. 2022, 44, 231–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick, K.; May, S. Critical Ethnography and Education: Theory, Methodology and Ethics; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Morse, J.M. Underlying ethnography. Qual. Health Res. 2016, 26, 875–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibbs, G. Learning by Doing: A Guide to Teaching and Learning Methods, Further Education Unit; Oxford Polytechnic: Oxford, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- May, T. Social Research: Issues, Methods and Process, 4th ed.; Open University Press: Maidenhead, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- British Educational Research Association. Ethical Guidelines for Educational Research; British Educational Research Association: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Students’ Project Activity | Data Collected | |

|---|---|---|

| Autumn |

| No data collected |

| Spring |

| No data collected |

| Summer |

|

|

| Themes | Codes and Categories | Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| Enjoyment | Enjoyment–(general: 5) -being actively involved (3) -rewarding (1) -working with children (4) | 13 |

| Challenges | Challenges– -challenges with technology (5) -initial confusion or uncertainty (5) | 10 |

| Developing skills | Developing skills– -developing communication and relationships (8) -developing confidence (15) -developing digital skills (7) -developing skills working with children (7) -developing skills of leadership (2) | 39 |

| Widening perspectives | Changemaking (2) Impact on own future– -impact on future (person) (5) -impact on future (work) (9) Widening perspectives (general: 6) -cultural competence (10) -part of a bigger picture (7) | 39 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Caldwell, H.; Whewell, E.; West, A.; Tiplady, H. Novel Spaces as Catalysts for Change: Transformative Learning through Transnational Projects. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 954. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14090954

Caldwell H, Whewell E, West A, Tiplady H. Novel Spaces as Catalysts for Change: Transformative Learning through Transnational Projects. Education Sciences. 2024; 14(9):954. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14090954

Chicago/Turabian StyleCaldwell, Helen, Emma Whewell, Amy West, and Helen Tiplady. 2024. "Novel Spaces as Catalysts for Change: Transformative Learning through Transnational Projects" Education Sciences 14, no. 9: 954. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14090954