Experiences of Cultural Differences, Discrimination, and Healthcare Access of Displaced Syrians (DS) in Lebanon: A Qualitative Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Sample

2.2. Interview Guides

2.3. Ethical Approval

2.4. Data Analysis and Trustworthiness

- 1.

- The research question was carefully crafted by the first author and thoroughly reviewed by the research team to ensure that it was clear and precise.

- 2.

- A diverse group of participants was selected for the study, including directors, healthcare professionals, and displaced Syrians, to ensure that a variety of viewpoints was reflected. We referred to the person triangulation and collected data from 3 types of people, with the aim of validating data through multiple perspectives.

- 3.

- The interviews were conducted in a neutral and non-judgmental manner, with open-ended questions that encouraged participants to share their experiences and opinions.

- 4.

- The interviews were conducted by a trained researcher who was skilled in qualitative research methods and who had experience working with diverse populations. A peer debriefing was used with knowledgeable peers and researchers on a qualitative basis.

- 5.

- The data collected from the interviews was carefully analyzed and interpreted using established research methods, including coding and thematic analysis. The findings were then reviewed and validated by multiple researchers to ensure that they were accurate and reliable, reflecting the experiences and perspectives of the participants.

- 6.

- Data saturation was reached once no new information was obtained and redundancy was achieved.

3. Results

3.1. Access and Entitlement of the DS to Lebanese Health System Services

3.1.1. Conditions for Hospital Admission

“UNHCR is represented by Next Care, an insurance company that covers hospitalization costs. But some cases are exempted such as chronic diseases, orthopedic prostheses, any surgery considered non-urgent (cold case) […] For infectious diseases requiring long-term treatment, the patient will not be admitted to the hospital if he cannot cover the expenses out-of-pocket since these cases are exempted as per the UNHCR agreement. For the amount that the patient must co-pay, we used a new procedure that requires the patient to cover these expenses upon admission to avoid any conflict upon discharge […] Honestly, sometimes, we call on the Security to make the patient pay the requested amount”(Jacques*—fictious name, director of a public hospital in Mount Lebanon).

“It took me a huge effort to explain and make them understand the organization of care in our center and the importance of respecting consultation times”(Farida, nurse at a PHC in Mount Lebanon).

“The DS are not organized […] besides, you can’t imagine, they believe that they can call the doctor at any time...it’s crazy, even for trivial questions, they call midnight. Frankly, I don’t know if they do the same thing in Syria […] they don’t understand that doctors are not employees who live in hospitals 24 h a day”(Jacques, director of a public hospital in Mount Lebanon).

“Third-party payers are always late to finance care for DS […]. So, sometimes I make a decision not to have DS admitted unless they put a deposit before their admission”(Jacques, director of a public hospital in Mount Lebanon).

3.1.2. Access of DS to Health Services

“Sometimes I don’t have the money to go to the center; I stay at home”(Ahmad, Syrian, 25 years).

“If they ask me for check-ups and x-rays, I don’t do them…I don’t have the money and I don’t come back to the center”(Fatima, Syrian, 27 years).

“The other time, a doctor told me I have to stay at home because I have COVID symptoms and it is contagious, but in the tent where I live we are 20 people […] I am not returning to this doctor and if I know I will be consulted by him again, I will flee”(Mohamad, Syrian, 32 years).

“Brochures and information in Arabic are offered in the PHC centers to allow them a better understanding of the health procedures carried out in these centers”(Joseph, director of a PHC).

“…It’s not that they don’t understand. The problem is that they don’t want to understand!”(Milad, director of a public hospital in Mount Lebanon).

“In our center (PHC-Hermel), we welcome any DS without asking for their identity or any legal document; you know that there are many Syrians who do not have their legal papers and who are sometimes afraid to go to the centers because they may be arrested by the Lebanese State”(Ali, nurse working at a PHC).

3.2. Socio-Cultural Interplays and Interactions between DS and Lebanese Healthcare Professionals

3.2.1. Socio-Cultural Differences

“One of the DS wanted to leave his newborn baby in the hospital because he does not want to pay the amount requested […]. Another left his wife and baby in the hospital because the woman gave birth to a girl and not a boy; it’s weird though. Also, a husband has asked his wife to have an abortion and he doesn’t care because he can have another one (he doesn’t want to pay…). I can also tell you that once we informed a father that his little one needed to be admitted to intensive care and there was an additional charge to be paid; he refused and replied, “it doesn’t matter if she dies; I don’t want to pay and I can have another” […] It’s still a bizarre attitude and mentality”(Jacques, director of a public hospital in Mount Lebanon).

“The Syrian doctor understands us; he gives us an injection in his clinic, and everything goes well […] here, the doctors ask for tests, and we don’t have the money to do them”(Ali, Syrian, 28 years).

3.2.2. Language Barriers

“It is very difficult to understand what they are saying, I am not familiar with their dialect… you know when we receive a Syrian who comes from the camps of Akkar, he speaks the “badawiyé” accent; frankly I do not understand anything; I make an effort to understand the signs and symptoms to know what to do. In Tripoli (northern Lebanon), it is easier since there is another community, and there are similarities between the two Lebanese and Syrian populations who share the same customs and values in general”(Fatima, nurse working at a PHC).

“Sometimes the doctor uses foreign language words or uses Lebanese words that I don’t understand, but I say nothing to him, and I pretend that I have understood, and I leave…”(Yusra, Syrian visiting a PHC in Akkar).

3.3. Health Inequity and Discrimination

“We sometimes encounter a problem of discrimination; especially with doctors who have a difficult character to manage… well you know they (doctors) consider that they occupy a particular position and that nobody can discuss it with them… We have received a lot of complaints from displaced Syrians about the sometimes inappropriate behavior of doctors. For example, one of the Syrian patients comes to tell me that a doctor told him to go to Syria to benefit from the care and that he gave up his place for a Lebanese.… Oooh what do we see cases, even doctors who refuse to see Syrian patients (only because he is Syrian), do you realize that?”(Fatima, nurse working at a PHC).

“The Lebanese always tell us that these centers are theirs and that we shouldn’t be here. We must return to our country”(Jafar, Syrian visiting a PHC).

“I come to this center because they behave better with us. The other time I was in a hospital, the doctor spoke to me in a disrespectful way and the nurse left me in the hallway for an hour without her speaking to me, yet she let other patients pass (Lebanese) smiling to them”(Yusra, Syria, 32 years).

“We had a lot of resistance from the staff at the hospital to work with the Syrians. The nurses complained about the smell and the hygiene of the Syrian patients (remember that they live in tents with miserable conditions) which pushed them to do things in a hurry and sometimes walk past symptoms without considering them. Following the various complaints received from patients (Lebanese), we were forced to put Syrian patients in separate rooms”(Nesrine, head nurse working at a hospital).

“To be frank with you, yes, there is discrimination between doctors/nurses and DS…it’s very human and don’t forget that we are Lebanese who lived through a war with Syria and we still have this feeling that they are “Syrians””(Mohamad, doctor consulting in a PHC).

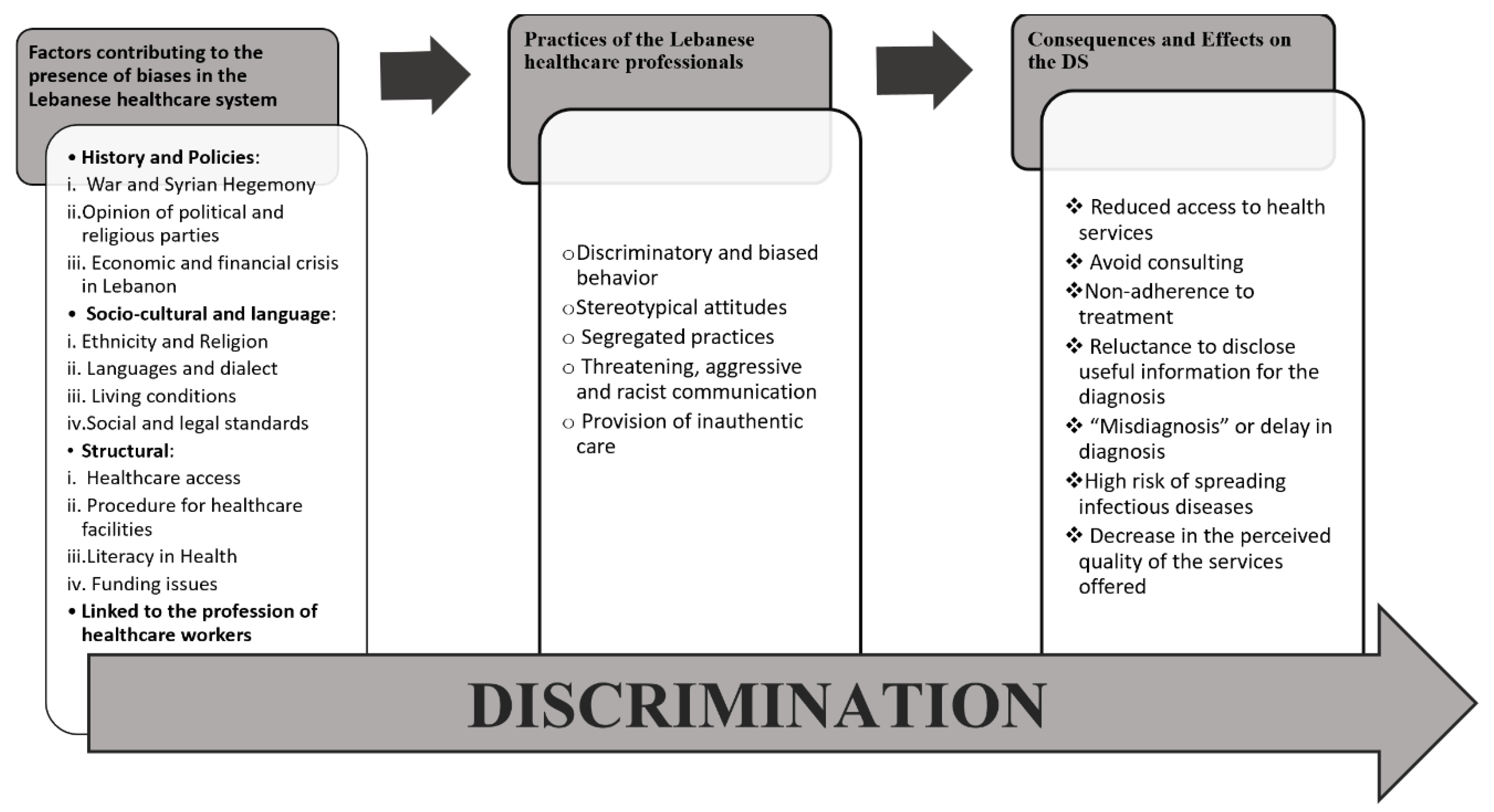

Factors Contributing to Health Inequity and Their Effects on DS in the Context of Lebanese Health System

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Limitations of the Study

4.2. Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations International Organisation of Migration (IOM). World Migration Report. 2020. Available online: https://worldmigrationreport.iom.int/wmr-2020-interactive/ (accessed on 10 November 2021).

- Vandan, N.; Wong, J.Y.; Lee, J.J.; Yip, P.S.; Fong, D.Y. Challenges of healthcare professionals in providing care to South Asian ethnic minority patients in Hong Kong: A qualitative study. Health Soc. Care Community 2020, 28, 591–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berti, B. The Syrian Refugee Crisis Regional and Human Security Implications. Strateg. Assess. 2015, 17, 41–53. [Google Scholar]

- Salem, P. Can Lebanon survive the syria crisis. In Carnegie Endowment for International Peace; JSTOR: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- UNHCR. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/lebanon.html (accessed on 25 September 2021).

- Geisser, V. La question des réfugiés syriens au Liban: Le réveil des fantômes du passé. Conflu. Méditerr. 2013, 87, 67–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, A.; Tanesini, A. Instilling new habits: Addressing implicit bias in healthcare professionals. Adv. Health Sci. Educ. 2015, 20, 1255–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandenberger, J.; Tylleskar, T.; Sontag, K.; Peterhans, B.; Ritz, N. A systematic literature review of reported challenges in health care delivery to migrants and refugees in high-income countries—The 3C model. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ojeleke, O.; Groot, W.; Pavlova, M. Care delivery among refugees and internally displaced persons affected by complex emergencies: A systematic review of the literature. J. Public Health 2020, 30, 747–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, P.F.; Martin, M.A. Proposal for a Code of Ethics or Intercultural Mediators in Healthcare. Ramon LIuII J. Appl. Ethics 2014, 29, 179–203. [Google Scholar]

- Gopal, D.P.; Chetty, U.; O’Donnell, P.; Gajria, C.; Blackadder-Weinstein, J. Implicit bias in healthcare: Clinical practice, research and decision making. Future Healthc. J. 2021, 8, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, D.R.; Lawrence, J.A.; Davis, B.A.; Vu, C. Understanding how discrimination can affect health. Health Serv. Res. 2019, 54 (Suppl. S2), 1374–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- UNHCR. 3RP Progress Report. 2017. Available online: https://data.unhcr.org/en/documents/details/60340 (accessed on 10 April 2021).

- Christiane, S.S. Recours aux Soins et Couverture Médicale au Liban. 5–7, Rue de l’Ecole-Polytechnique; L’Harmattan: Paris, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Khalife, J.R.N.; Makouk, J.; ElJardali, F.; Ekman, B.; Kronfol, N.; Hamadeh, G.; Ammar, W. Hospital Contracting Reforms the Lebanese. J. Health Syst. Reform 2017, 3, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammar, Z. Health Response Strategy. 2016. Available online: https://www.moph.gov.lb/en/publications (accessed on 4 April 2021).

- El Arnaout, N.; Rutherford, S.; Zreik, T.; Nabulsi, D.; Yassin, N.; Saleh, S. Assessment of the health needs of Syrian refugees in Lebanon and Syria’s neighboring countries. Confl. Health 2019, 13, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Parkinson, S.E.; Behrouzan, O. Negotiating health and life: Syrian refugees and the politics of access in Lebanon. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 146, 324–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sousa, C.; Akesson, B.; Badawi, D. ‘Most importantly, I hope God keeps illness away from us’: The context and challenges surrounding access to health care for Syrian refugees in Lebanon. Glob. Public Health 2020, 15, 1617–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorleifsson, C. The limits of hospitality: Coping strategies among displaced Syrians in Lebanon. Third World Q. 2016, 37, 1071–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, G. Nursing Research—Generating and Assessing Evidence for Nursing Practice. Nurse Res. 2010, 17, 88–89. [Google Scholar]

- Ghaddar, A.; Khandaqji, S.; Kansoun, R.; Ghassani, A. Access of Syrian refugees to COVID-19 testing in Lebanon. East. Mediterr. Health J. 2023, 29, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feinberg, I.; O’Connor, M.H.; Owen-Smith, A.; Ogrodnick, M.M.; Rothenberg, R. The Relationship Between Refugee Health Status and Language, Literacy, and Time Spent in the United States. Health Lit. Res. Pract. 2020, 4, e230–e236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, M.; Maina, R.G.; Amoyaw, J.; Li, Y.; Kamrul, R.; Michaels, C.R.; Maroof, R. Impacts of English language proficiency on healthcare access, use, and outcomes among immigrants: A qualitative study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vissandjée, B.; Dupére, S. La communication interculturelle en contexte clinique. Can. J. Nurs. Res. Arch. 2000, 32, 99–113. [Google Scholar]

- Bouclaous, C.; Haddad, I.; Alrazim, A.; Kolanjian, H.; El Safadi, A. Health literacy levels and correlates among refugees in Mount Lebanon. Public Health 2021, 199, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, S.S.; Heydon, S.; Norris, P. Access to the healthcare system: Experiences and perspectives of Pakistani immigrant mothers in New Zealand. J. Migr. Health 2022, 5, 100077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivenbark, J.G.; Ichou, M. Discrimination in healthcare as a barrier to care: Experiences of socially disadvantaged populations in France from a nationally representative survey. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Småland Goth, U.G.; Berg, J.E. Migrant participation in Norwegian health care. A qualitative study using key informants. Eur. J. Gen. Pract. 2011, 17, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Saliba, C.E.E. Sexual violence in the Lebanese confessional denomination society. Hadatha 2021, 217, 9–28. [Google Scholar]

- Alpern, J.D.; Davey, C.S.; Song, J. Perceived barriers to success for resident physicians interested in immigrant and refugee health. BMC Med. Educ. 2016, 16, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marcelin, J.R.; Siraj, D.S.; Victor, R.; Kotadia, S.; Maldonado, Y.A. The Impact of Unconscious Bias in Healthcare: How to Recognize and Mitigate It. J. Infect. Dis. 2019, 220, S62–S73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- FitzGerald, C.; Hurst, S. Implicit bias in healthcare professionals: A systematic review. BMC Med. Ethics 2017, 18, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Akbarzada, S.; Mackey, T.K. The Syrian public health and humanitarian crisis: A ‘displacement’ in global governance? Glob. Public Health 2018, 13, 914–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausmann, L.R.; Jeong, K.; Bost, J.E.; Ibrahim, S.A. Perceived discrimination in health care and health status in a racially diverse sample. Med. Care 2008, 46, 905–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sorkin, D.H.; Ngo-Metzger, Q.; De Alba, I. Racial/ethnic discrimination in health care: Impact on perceived quality of care. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2010, 25, 390–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Purnell, T.S.; Calhoun, E.A.; Golden, S.H.; Halladay, J.R.; Krok-Schoen, J.L.; Appelhans, B.M.; Cooper, L.A. Achieving Health Equity: Closing The Gaps In Health Care Disparities, Interventions, And Research. Health Aff. 2016, 35, 1410–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hamed, S.; Thapar-Björkert, S.; Bradby, H.; Ahlberg, B.M. Racism in European Health Care: Structural Violence and Beyond. Qual. Health Res. 2020, 30, 1662–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kikano, F.; Fauveaud, G.; Lizarralde, G. Policies of Exclusion: The Case of Syrian Refugees in Lebanon. J. Refug. Stud. 2021, 34, 422–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaki, F.M.; Alani, O.; Tannoury, M.; Ezzeddine, F.L.; Snyder, R.E.; Waked, A.N.; Attieh, Z. Noncommunicable Disease and Health Care-Seeking Behavior Among Urban Camp-Dwelling Syrian Refugees in Lebanon: A Preliminary Investigation. Health Equity 2021, 5, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Participants | Code | Number of Participants (n = 20) | Participants’ Sex | Mean Age of Participants | Academic Qualification | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | F | |||||

| Category 1: Administrators of Health Facilities | E_D_PX | 5 | 3 | 2 | 47 | Healthcare Management (n = 3), Doctors (n = 2) |

| Category 2: Health Professionals | E_PS_PX | 9 | 6 | 3 | 38.5 | Nurse (n = 5), Medical Doctor-General Practitioners (n = 4) |

| Category 3: Displaced Syrians | E_DS_PX | 6 | 2 | 4 | 40.5 | N/A |

| Participants | Objectives of the Interview Guide |

|---|---|

| Administrators of health facilities |

|

| Health Professionals |

|

| Displaced Syrians |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Khalifeh, R.; D’Hoore, W.; Saliba, C.; Salameh, P.; Dauvrin, M. Experiences of Cultural Differences, Discrimination, and Healthcare Access of Displaced Syrians (DS) in Lebanon: A Qualitative Study. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2013. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11142013

Khalifeh R, D’Hoore W, Saliba C, Salameh P, Dauvrin M. Experiences of Cultural Differences, Discrimination, and Healthcare Access of Displaced Syrians (DS) in Lebanon: A Qualitative Study. Healthcare. 2023; 11(14):2013. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11142013

Chicago/Turabian StyleKhalifeh, Riwa, William D’Hoore, Christiane Saliba, Pascale Salameh, and Marie Dauvrin. 2023. "Experiences of Cultural Differences, Discrimination, and Healthcare Access of Displaced Syrians (DS) in Lebanon: A Qualitative Study" Healthcare 11, no. 14: 2013. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11142013